|

Climate is the long-term average of weather, typically averaged over a period of 30 years. More rigorously, it is the mean and variability of meteorological variables over a time spanning from months to millions of years. Some of the meteorological variables that are commonly measured are temperature, humidity, atmospheric pressure, wind, and precipitation. In a broader sense, climate is the state of the components of the climate system, which includes the ocean and ice on Earth. The climate of a location is affected by its latitude, terrain, and altitude, as well as nearby water bodies and their currents.

Climates can be classified according to the average and the typical ranges of different variables, most commonly temperature and precipitation. The most commonly used classification scheme was the Köppen climate classification. The Thornthwaite system, in use since 1948, incorporates evapotranspiration along with temperature and precipitation information and is used in studying biological diversity and how climate change affects it. The Bergeron and Spatial Synoptic Classification systems focus on the origin of air masses that define the climate of a region.

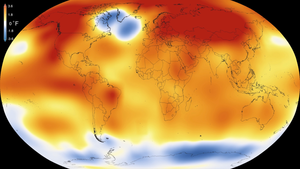

Paleoclimatology is the study of ancient climates. Since very few direct observations of climate are available before the 19th century, paleoclimates are inferred from proxy variables that include non-biotic evidence such as sediments found in lake beds and ice cores, and biotic evidence such as tree rings and coral. Climate models are mathematical models of past, present and future climates. Climate change may occur over long and short timescales from a variety of factors; recent warming is discussed in global warming. Global warming results in redistributions. For example, "a 3°C change in mean annual temperature corresponds to a shift in isotherms of approximately 300–400 km in latitude (in the temperate zone) or 500 m in elevation. Therefore, species are expected to move upwards in elevation or towards the poles in latitude in response to shifting climate zones".

Definition

Climate (from Ancient Greek klima, meaning inclination) is commonly defined as the weather averaged over a long period. The standard averaging period is 30 years, but other periods may be used depending on the purpose. Climate also includes statistics other than the average, such as the magnitudes of day-to-day or year-to-year variations. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 2001 glossary definition is as follows:

Climate in a narrow sense is usually defined as the "average weather," or more rigorously, as the statistical description in terms of the mean and variability of relevant quantities over a period ranging from months to thousands or millions of years. The classical period is 30 years, as defined by the World Meteorological Organization (WMO). These quantities are most often surface variables such as temperature, precipitation, and wind. Climate in a wider sense is the state, including a statistical description, of the climate system.

The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) describes "climate normals" (CN) as "reference points used by climatologists to compare current climatological trends to that of the past or what is considered typical. A CN is defined as the arithmetic average of a climate element (e.g. temperature) over a 30-year period. A 30 year period is used, as it is long enough to filter out any interannual variation or anomalies, but also short enough to be able to show longer climatic trends."

The WMO originated from the International Meteorological Organization which set up a technical commission for climatology in 1929. At its 1934 Wiesbaden meeting the technical commission designated the thirty-year period from 1901 to 1930 as the reference time frame for climatological standard normals. In 1982 the WMO agreed to update climate normals, and these were subsequently completed on the basis of climate data from 1 January 1961 to 31 December 1990.

The difference between climate and weather is usefully summarized by the popular phrase "Climate is what you expect, weather is what you get." Over historical time spans, there are a number of nearly constant variables that determine climate, including latitude, altitude, proportion of land to water, and proximity to oceans and mountains. All of these variables change only over periods of millions of years due to processes such as plate tectonics. Other climate determinants are more dynamic: the thermohaline circulation of the ocean leads to a 5 °C (9 °F) warming of the northern Atlantic Ocean compared to other ocean basins. Other ocean currents redistribute heat between land and water on a more regional scale. The density and type of vegetation coverage affects solar heat absorption, water retention, and rainfall on a regional level. Alterations in the quantity of atmospheric greenhouse gases determines the amount of solar energy retained by the planet, leading to global warming or global cooling. The variables which determine climate are numerous and the interactions complex, but there is general agreement that the broad outlines are understood, at least insofar as the determinants of historical climate change are concerned.

Climate classification

There are several ways to classify climates into similar regimes. Originally, climes were defined in Ancient Greece to describe the weather depending upon a location's latitude. Modern climate classification methods can be broadly divided into genetic methods, which focus on the causes of climate, and empiric methods, which focus on the effects of climate. Examples of genetic classification include methods based on the relative frequency of different air mass types or locations within synoptic weather disturbances. Examples of empiric classifications include climate zones defined by plant hardiness, evapotranspiration, or more generally the Köppen climate classification which was originally designed to identify the climates associated with certain biomes. A common shortcoming of these classification schemes is that they produce distinct boundaries between the zones they define, rather than the gradual transition of climate properties more common in nature.

Bergeron and Spatial Synoptic

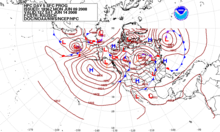

The simplest classification is that involving air masses. The Bergeron classification is the most widely accepted form of air mass classification. Air mass classification involves three letters. The first letter describes its moisture properties, with c used for continental air masses (dry) and m for maritime air masses (moist). The second letter describes the thermal characteristic of its source region: T for tropical, P for polar, A for Arctic or Antarctic, M for monsoon, E for equatorial, and S for superior air (dry air formed by significant downward motion in the atmosphere). The third letter is used to designate the stability of the atmosphere. If the air mass is colder than the ground below it, it is labeled k. If the air mass is warmer than the ground below it, it is labeled w. While air mass identification was originally used in weather forecasting during the 1950s, climatologists began to establish synoptic climatologies based on this idea in 1973.

Based upon the Bergeron classification scheme is the Spatial Synoptic Classification system (SSC). There are six categories within the SSC scheme: Dry Polar (similar to continental polar), Dry Moderate (similar to maritime superior), Dry Tropical (similar to continental tropical), Moist Polar (similar to maritime polar), Moist Moderate (a hybrid between maritime polar and maritime tropical), and Moist Tropical (similar to maritime tropical, maritime monsoon, or maritime equatorial).

Köppen

The Köppen classification depends on average monthly values of temperature and precipitation. The most commonly used form of the Köppen classification has five primary types labeled A through E. These primary types are A) tropical, B) dry, C) mild mid-latitude, D) cold mid-latitude, and E) polar. The five primary classifications can be further divided into secondary classifications such as rainforest, monsoon, tropical savanna, humid subtropical, humid continental, oceanic climate, Mediterranean climate, desert, steppe, subarctic climate, tundra, and polar ice cap.

Rainforests are characterized by high rainfall, with definitions setting minimum normal annual rainfall between 1,750 millimetres (69 in) and 2,000 millimetres (79 in). Mean monthly temperatures exceed 18 °C (64 °F) during all months of the year.

A monsoon is a seasonal prevailing wind which lasts for several months, ushering in a region's rainy season. Regions within North America, South America, Sub-Saharan Africa, Australia and East Asia are monsoon regimes.

A tropical savanna is a grassland biome located in semi-arid to semi-humid climate regions of subtropical and tropical latitudes, with average temperatures remaining at or above 18 °C (64 °F) all year round, and rainfall between 750 millimetres (30 in) and 1,270 millimetres (50 in) a year. They are widespread on Africa, and are found in India, the northern parts of South America, Malaysia, and Australia.

The humid subtropical climate zone where winter rainfall (and sometimes snowfall) is associated with large storms that the westerlies steer from west to east. Most summer rainfall occurs during thunderstorms and from occasional tropical cyclones. Humid subtropical climates lie on the east side of continents, roughly between latitudes 20° and 40° degrees away from the equator.

A humid continental climate is marked by variable weather patterns and a large seasonal temperature variance. Places with more than three months of average daily temperatures above 10 °C (50 °F) and a coldest month temperature below −3 °C (27 °F) and which do not meet the criteria for an arid or semi-arid climate, are classified as continental.

An oceanic climate is typically found along the west coasts at the middle latitudes of all the world's continents, and in southeastern Australia, and is accompanied by plentiful precipitation year-round.

The Mediterranean climate regime resembles the climate of the lands in the Mediterranean Basin, parts of western North America, parts of Western and South Australia, in southwestern South Africa and in parts of central Chile. The climate is characterized by hot, dry summers and cool, wet winters.

A steppe is a dry grassland with an annual temperature range in the summer of up to 40 °C (104 °F) and during the winter down to −40 °C (−40 °F).

A subarctic climate has little precipitation, and monthly temperatures which are above 10 °C (50 °F) for one to three months of the year, with permafrost in large parts of the area due to the cold winters. Winters within subarctic climates usually include up to six months of temperatures averaging below 0 °C (32 °F).

Tundra occurs in the far Northern Hemisphere, north of the taiga belt, including vast areas of northern Russia and Canada.

A polar ice cap, or polar ice sheet, is a high-latitude region of a planet or moon that is covered in ice. Ice caps form because high-latitude regions receive less energy as solar radiation from the sun than equatorial regions, resulting in lower surface temperatures.

A desert is a landscape form or region that receives very little precipitation. Deserts usually have a large diurnal and seasonal temperature range, with high or low, depending on location daytime temperatures (in summer up to 45 °C or 113 °F), and low nighttime temperatures (in winter down to 0 °C or 32 °F) due to extremely low humidity. Many deserts are formed by rain shadows, as mountains block the path of moisture and precipitation to the desert.

Thornthwaite

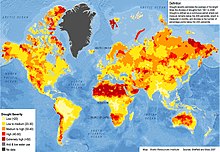

Devised by the American climatologist and geographer C. W. Thornthwaite, this climate classification method monitors the soil water budget using evapotranspiration. It monitors the portion of total precipitation used to nourish vegetation over a certain area. It uses indices such as a humidity index and an aridity index to determine an area's moisture regime based upon its average temperature, average rainfall, and average vegetation type. The lower the value of the index in any given area, the drier the area is.

The moisture classification includes climatic classes with descriptors such as hyperhumid, humid, subhumid, subarid, semi-arid (values of −20 to −40), and arid (values below −40). Humid regions experience more precipitation than evaporation each year, while arid regions experience greater evaporation than precipitation on an annual basis. A total of 33 percent of the Earth's landmass is considered either arid or semi-arid, including southwest North America, southwest South America, most of northern and a small part of southern Africa, southwest and portions of eastern Asia, as well as much of Australia. Studies suggest that precipitation effectiveness (PE) within the Thornthwaite moisture index is overestimated in the summer and underestimated in the winter. This index can be effectively used to determine the number of herbivore and mammal species numbers within a given area. The index is also used in studies of climate change.

Thermal classifications within the Thornthwaite scheme include microthermal, mesothermal, and megathermal regimes. A microthermal climate is one of low annual mean temperatures, generally between 0 °C (32 °F) and 14 °C (57 °F) which experiences short summers and has a potential evaporation between 14 centimetres (5.5 in) and 43 centimetres (17 in). A mesothermal climate lacks persistent heat or persistent cold, with potential evaporation between 57 centimetres (22 in) and 114 centimetres (45 in). A megathermal climate is one with persistent high temperatures and abundant rainfall, with potential annual evaporation in excess of 114 centimetres (45 in).

Record

Paleoclimatology

Paleoclimatology is the study of past climate over a great period of the Earth's history. It uses evidence from ice sheets, tree rings, sediments, coral, and rocks to determine the past state of the climate. It demonstrates periods of stability and periods of change and can indicate whether changes follow patterns such as regular cycles.

Modern

Details of the modern climate record are known through the taking of measurements from such weather instruments as thermometers, barometers, and anemometers during the past few centuries. The instruments used to study weather over the modern time scale, their known error, their immediate environment, and their exposure have changed over the years, which must be considered when studying the climate of centuries past.

Climate variability

Climate variability is the term to describe variations in the mean state and other characteristics of climate (such as chances or possibility of extreme weather, etc.) "on all spatial and temporal scales beyond that of individual weather events." Some of the variability does not appear to be caused systematically and occurs at random times. Such variability is called random variability or noise. On the other hand, periodic variability occurs relatively regularly and in distinct modes of variability or climate patterns.

There are close correlations between Earth's climate oscillations and astronomical factors (barycenter changes, solar variation, cosmic ray flux, cloud albedo feedback, Milankovic cycles), and modes of heat distribution between the ocean-atmosphere climate system. In some cases, current, historical and paleoclimatological natural oscillations may be masked by significant volcanic eruptions, impact events, irregularities in climate proxy data, positive feedback processes or anthropogenic emissions of substances such as greenhouse gases.

Over the years, the definitions of climate variability and the related term climate change have shifted. While the term climate change now implies change that is both long-term and of human causation, in the 1960s the word climate change was used for what we now describe as climate variability, that is, climatic inconsistencies and anomalies.

Climate change

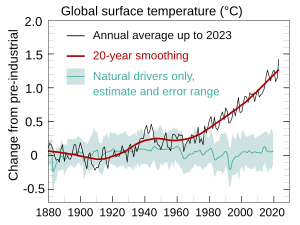

Climate change is the variation in global or regional climates over time. It reflects changes in the variability or average state of the atmosphere over time scales ranging from decades to millions of years. These changes can be caused by processes internal to the Earth, external forces (e.g. variations in sunlight intensity) or, more recently, human activities. In recent usage, especially in the context of environmental policy, the term "climate change" often refers only to changes in modern climate, including the rise in average surface temperature known as global warming. In some cases, the term is also used with a presumption of human causation, as in the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). The UNFCCC uses "climate variability" for non-human caused variations.

Earth has undergone periodic climate shifts in the past, including four major ice ages. These consisting of glacial periods where conditions are colder than normal, separated by interglacial periods. The accumulation of snow and ice during a glacial period increases the surface albedo, reflecting more of the Sun's energy into space and maintaining a lower atmospheric temperature. Increases in greenhouse gases, such as by volcanic activity, can increase the global temperature and produce an interglacial period. Suggested causes of ice age periods include the positions of the continents, variations in the Earth's orbit, changes in the solar output, and volcanism.

Climate models

Climate models use quantitative methods to simulate the interactions of the atmosphere, oceans, land surface and ice. They are used for a variety of purposes; from the study of the dynamics of the weather and climate system, to projections of future climate. All climate models balance, or very nearly balance, incoming energy as short wave (including visible) electromagnetic radiation to the earth with outgoing energy as long wave (infrared) electromagnetic radiation from the earth. Any imbalance results in a change in the average temperature of the earth.

The most talked-about applications of these models in recent years have been their use to infer the consequences of increasing greenhouse gases in the atmosphere, primarily carbon dioxide (see greenhouse gas). These models predict an upward trend in the global mean surface temperature, with the most rapid increase in temperature being projected for the higher latitudes of the Northern Hemisphere.

Models can range from relatively simple to quite complex:

- Simple radiant heat transfer model that treats the earth as a single point and averages outgoing energy

- this can be expanded vertically (radiative-convective models), or horizontally

- finally, (coupled) atmosphere–ocean–sea ice global climate models discretise and solve the full equations for mass and energy transfer and radiant exchange.