Jean-Jacques Rousseau | |

|---|---|

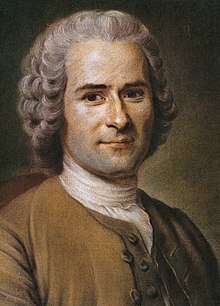

Rousseau by Maurice Quentin de La Tour, 1753 | |

| Born | 28 June 1712 |

| Died | 2 July 1778 (aged 66) |

| Partner(s) | Thérèse Levasseur (1745–1778; his death) |

| Era | 18th-century philosophy (early modern philosophy) |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Social contract Romanticism |

Main interests | Political philosophy, music, education, literature, autobiography |

Notable ideas | General will, amour de soi, amour-propre, moral simplicity of humanity, child-centered learning, civil religion, popular sovereignty, positive liberty, public opinion |

| Signature | |

|---|---|

|

Jean-Jacques Rousseau (UK: /ˈruːsoʊ/, US: /ruːˈsoʊ/; French: [ʒɑ̃ ʒak ʁuso]; 28 June 1712 – 2 July 1778) was a Genevan philosopher, writer, and composer. His political philosophy influenced the progress of the Enlightenment throughout Europe, as well as aspects of the French Revolution and the development of modern political, economic and educational thought.

His Discourse on Inequality and The Social Contract are cornerstones in modern political and social thought. Rousseau's sentimental novel Julie, or the New Heloise (1761) was important to the development of preromanticism and romanticism in fiction. His Emile, or On Education (1762) is an educational treatise on the place of the individual in society. Rousseau's autobiographical writings—the posthumously published Confessions (composed in 1769), which initiated the modern autobiography, and the unfinished Reveries of the Solitary Walker (composed 1776–1778)—exemplified the late-18th-century "Age of Sensibility", and featured an increased focus on subjectivity and introspection that later characterized modern writing.

Rousseau befriended fellow philosopher Denis Diderot in 1742, and would later write about Diderot's romantic troubles in his Confessions. During the period of the French Revolution, Rousseau was the most popular of the philosophers among members of the Jacobin Club. He was interred as a national hero in the Panthéon in Paris, in 1794, 16 years after his death.

Biography

Youth

Rousseau was born in Geneva, which was at the time a city-state and a Protestant associate of the Swiss Confederacy. Since 1536, Geneva had been a Huguenot republic and the seat of Calvinism. Five generations before Rousseau, his ancestor Didier, a bookseller who may have published Protestant tracts, had escaped persecution from French Catholics by fleeing to Geneva in 1549, where he became a wine merchant.

Rousseau was proud that his family, of the moyen order (or middle-class), had voting rights in the city. Throughout his life, he generally signed his books "Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Citizen of Geneva".

Geneva, in theory, was governed "democratically" by its male voting "citizens". The citizens were a minority of the population when compared to the immigrants, referred to as "inhabitants", whose descendants were called "natives" and continued to lack suffrage. In fact, rather than being run by vote of the "citizens", the city was ruled by a small number of wealthy families that made up the "Council of Two Hundred"; these delegated their power to a 25-member executive group from among them called the "Little Council".

There was much political debate within Geneva, extending down to the tradespeople. Much discussion was over the idea of the sovereignty of the people, of which the ruling class oligarchy was making a mockery. In 1707, a democratic reformer named Pierre Fatio protested this situation, saying "a sovereign that never performs an act of sovereignty is an imaginary being". He was shot by order of the Little Council. Jean-Jacques Rousseau's father, Isaac, was not in the city at this time, but Jean-Jacques's grandfather supported Fatio and was penalized for it.

Rousseau's father, Isaac Rousseau, followed his grandfather, father and brothers into the watchmaking business. He also taught dance for a short period. Isaac, notwithstanding his artisan status, was well educated and a lover of music. Rousseau wrote that "A Genevan watchmaker is a man who can be introduced anywhere; a Parisian watchmaker is only fit to talk about watches".

In 1699, Isaac ran into political difficulty by entering a quarrel with visiting English officers, who in response drew their swords and threatened him. After local officials stepped in, it was Isaac who was punished, as Geneva was concerned with maintaining its ties to foreign powers.

Rousseau's mother, Suzanne Bernard Rousseau, was from an upper-class family. She was raised by her uncle Samuel Bernard, a Calvinist preacher. He cared for Suzanne after her father, Jacques, who had run into trouble with the legal and religious authorities for fornication and having a mistress, died in his early 30s. In 1695, Suzanne had to answer charges that she had attended a street theater disguised as a peasant woman so she could gaze upon M. Vincent Sarrasin, whom she fancied despite his continuing marriage. After a hearing, she was ordered by the Genevan Consistory to never interact with him again. She married Rousseau's father at the age of 31. Isaac's sister had married Suzanne's brother eight years earlier, after she had become pregnant and they had been chastised by the Consistory. The child died at birth. The young Rousseau was told a fabricated story about the situation in which young love had been denied by a disapproving patriarch but later prevailed, resulting in two marriages uniting the families on the same day. Rousseau never learnt the truth.

Rousseau was born on 28 June 1712, and he would later relate: "I was born almost dying, they had little hope of saving me". He was baptized on 4 July 1712, in the great cathedral. His mother died of puerperal fever nine days after his birth, which he later described as "the first of my misfortunes".

He and his older brother François were brought up by their father and a paternal aunt, also named Suzanne. When Rousseau was five, his father sold the house that the family had received from his mother's relatives. While the idea was that his sons would inherit the principal when grown up and he would live off the interest in the meantime, in the end the father took most of the substantial proceeds.With the selling of the house, the Rousseau family moved out of the upper-class neighborhood and moved into an apartment house in a neighborhood of craftsmen—silversmiths, engravers, and other watchmakers. Growing up around craftsmen, Rousseau would later contrast them favorably to those who produced more aesthetic works, writing "those important persons who are called artists rather than artisans, work solely for the idle and rich, and put an arbitrary price on their baubles". Rousseau was also exposed to class politics in this environment, as the artisans often agitated in a campaign of resistance against the privileged class running Geneva.

Rousseau had no recollection of learning to read, but he remembered how when he was five or six his father encouraged his love of reading:

Every night, after supper, we read some part of a small collection of romances [adventure stories], which had been my mother's. My father's design was only to improve me in reading, and he thought these entertaining works were calculated to give me a fondness for it; but we soon found ourselves so interested in the adventures they contained, that we alternately read whole nights together and could not bear to give over until at the conclusion of a volume. Sometimes, in the morning, on hearing the swallows at our window, my father, quite ashamed of this weakness, would cry, "Come, come, let us go to bed; I am more a child than thou art." (Confessions, Book 1)

Rousseau's reading of escapist stories (such as L'Astrée by Honoré d'Urfé) had an effect on him; he later wrote that they "gave me bizarre and romantic notions of human life, which experience and reflection have never been able to cure me of". After they had finished reading the novels, they began to read a collection of ancient and modern classics left by his mother's uncle. Of these, his favorite was Plutarch's Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans, which he would read to his father while he made watches. Rousseau saw Plutarch's work as another kind of novel—the noble actions of heroes—and he would act out the deeds of the characters he was reading about. In his Confessions, Rousseau stated that the reading of Plutarch's works and "the conversations between my father and myself to which it gave rise, formed in me the free and republican spirit".

Witnessing the local townsfolk participate in militias made a big impression on Rousseau. Throughout his life, he would recall one scene where, after the volunteer militia had finished its manoeuvres, they began to dance around a fountain and most of the people from neighboring buildings came out to join them, including him and his father. Rousseau would always see militias as the embodiment of popular spirit in opposition to the armies of the rulers, whom he saw as disgraceful mercenaries.

When Rousseau was ten, his father, an avid hunter, got into a legal quarrel with a wealthy landowner on whose lands he had been caught trespassing. To avoid certain defeat in the courts, he moved away to Nyon in the territory of Bern, taking Rousseau's aunt Suzanne with him. He remarried, and from that point Jean-Jacques saw little of him. Jean-Jacques was left with his maternal uncle, who packed him, along with his own son, Abraham Bernard, away to board for two years with a Calvinist minister in a hamlet outside Geneva. Here, the boys picked up the elements of mathematics and drawing. Rousseau, who was always deeply moved by religious services, for a time even dreamed of becoming a Protestant minister.

Virtually all our information about Rousseau's youth has come from his posthumously published Confessions, in which the chronology is somewhat confused, though recent scholars have combed the archives for confirming evidence to fill in the blanks. At age 13, Rousseau was apprenticed first to a notary and then to an engraver who beat him. At 15, he ran away from Geneva (on 14 March 1728) after returning to the city and finding the city gates locked due to the curfew.

In adjoining Savoy he took shelter with a Roman Catholic priest, who introduced him to Françoise-Louise de Warens, age 29. She was a noblewoman of Protestant background who was separated from her husband. As professional lay proselytizer, she was paid by the King of Piedmont to help bring Protestants to Catholicism. They sent the boy to Turin, the capital of Savoy (which included Piedmont, in what is now Italy), to complete his conversion. This resulted in his having to give up his Genevan citizenship, although he would later revert to Calvinism to regain it.

In converting to Catholicism, both de Warens and Rousseau were likely reacting to Calvinism's insistence on the total depravity of man. Leo Damrosch writes: "An eighteenth-century Genevan liturgy still required believers to declare 'that we are miserable sinners, born in corruption, inclined to evil, incapable by ourselves of doing good'". De Warens, a deist by inclination, was attracted to Catholicism's doctrine of forgiveness of sins.

Finding himself on his own, since his father and uncle had more or less disowned him, the teenage Rousseau supported himself for a time as a servant, secretary, and tutor, wandering in Italy (Piedmont and Savoy) and France. During this time, he lived on and off with de Warens, whom he idolized and called his maman. Flattered by his devotion, de Warens tried to get him started in a profession, and arranged formal music lessons for him. At one point, he briefly attended a seminary with the idea of becoming a priest.

Early adulthood

When Rousseau reached 20, de Warens took him as her lover, while intimate also with the steward of her house. The sexual aspect of their relationship (a ménage à trois) confused Rousseau and made him uncomfortable, but he always considered de Warens the greatest love of his life. A rather profligate spender, she had a large library and loved to entertain and listen to music. She and her circle, comprising educated members of the Catholic clergy, introduced Rousseau to the world of letters and ideas. Rousseau had been an indifferent student, but during his 20s, which were marked by long bouts of hypochondria, he applied himself in earnest to the study of philosophy, mathematics, and music. At 25, he came into a small inheritance from his mother and used a portion of it to repay de Warens for her financial support of him. At 27, he took a job as a tutor in Lyon.

In 1742, Rousseau moved to Paris to present the Académie des Sciences with a new system of numbered musical notation he believed would make his fortune. His system, intended to be compatible with typography, is based on a single line, displaying numbers representing intervals between notes and dots and commas indicating rhythmic values. Believing the system was impractical, the Academy rejected it, though they praised his mastery of the subject, and urged him to try again. He befriended Denis Diderot that year, connecting over the discussion of literary endeavors.

From 1743 to 1744, Rousseau had an honorable but ill-paying post as a secretary to the Comte de Montaigue, the French ambassador to Venice. This awoke in him a lifelong love for Italian music, particularly opera:

I had brought with me from Paris the prejudice of that city against Italian music; but I had also received from nature a sensibility and niceness of distinction which prejudice cannot withstand. I soon contracted that passion for Italian music with which it inspires all those who are capable of feeling its excellence. In listening to barcaroles, I found I had not yet known what singing was...

— Confessions

Rousseau's employer routinely received his stipend as much as a year late and paid his staff irregularly. After 11 months, Rousseau quit, taking from the experience a profound distrust of government bureaucracy.

Return to Paris

Returning to Paris, the penniless Rousseau befriended and became the lover of Thérèse Levasseur, a seamstress who was the sole support of her mother and numerous ne'er-do-well siblings. At first, they did not live together, though later Rousseau took Thérèse and her mother in to live with him as his servants, and himself assumed the burden of supporting her large family. According to his Confessions, before she moved in with him, Thérèse bore him a son and as many as four other children (there is no independent verification for this number).

Rousseau wrote that he persuaded Thérèse to give each of the newborns up to a foundling hospital, for the sake of her "honor". "Her mother, who feared the inconvenience of a brat, came to my aid, and she [Thérèse] allowed herself to be overcome" (Confessions). In his letter to Madame de Francueil in 1751, he first pretended that he wasn't rich enough to raise his children, but in Book IX of the Confessions he gave the true reasons of his choice: "I trembled at the thought of intrusting them to a family ill brought up, to be still worse educated. The risk of the education of the foundling hospital was much less".

Ten years later, Rousseau made inquiries about the fate of his son, but no record could be found. When Rousseau subsequently became celebrated as a theorist of education and child-rearing, his abandonment of his children was used by his critics, including Voltaire and Edmund Burke, as the basis for ad hominem attacks.

Beginning with some articles on music in 1749, Rousseau contributed numerous articles to Diderot and D'Alembert's great Encyclopédie, the most famous of which was an article on political economy written in 1755.

Rousseau's ideas were the result of an almost obsessive dialogue with writers of the past, filtered in many cases through conversations with Diderot. In 1749, Rousseau was paying daily visits to Diderot, who had been thrown into the fortress of Vincennes under a lettre de cachet for opinions in his "Lettre sur les aveugles", that hinted at materialism, a belief in atoms, and natural selection. According to science historian Conway Zirkle, Rousseau saw the concept of natural selection "as an agent for improving the human species."

Rousseau had read about an essay competition sponsored by the Académie de Dijon to be published in the Mercure de France on the theme of whether the development of the arts and sciences had been morally beneficial. He wrote that while walking to Vincennes (about three miles from Paris), he had a revelation that the arts and sciences were responsible for the moral degeneration of mankind, who were basically good by nature. Rousseau's 1750 Discourse on the Arts and Sciences was awarded the first prize and gained him significant fame.

Rousseau continued his interest in music. He wrote both the words and music of his opera Le devin du village (The Village Soothsayer), which was performed for King Louis XV in 1752. The king was so pleased by the work that he offered Rousseau a lifelong pension. To the exasperation of his friends, Rousseau turned down the great honor, bringing him notoriety as "the man who had refused a king's pension". He also turned down several other advantageous offers, sometimes with a brusqueness bordering on truculence that gave offense and caused him problems. The same year, the visit of a troupe of Italian musicians to Paris, and their performance of Giovanni Battista Pergolesi's La serva padrona, prompted the Querelle des Bouffons, which pitted protagonists of French music against supporters of the Italian style. Rousseau as noted above, was an enthusiastic supporter of the Italians against Jean-Philippe Rameau and others, making an important contribution with his Letter on French Music.

Return to Geneva

On returning to Geneva in 1754, Rousseau reconverted to Calvinism and regained his official Genevan citizenship. In 1755, Rousseau completed his second major work, the Discourse on the Origin and Basis of Inequality Among Men (the Discourse on Inequality), which elaborated on the arguments of the Discourse on the Arts and Sciences.

He also pursued an unconsummated romantic attachment with the 25-year-old Sophie d'Houdetot, which partly inspired his epistolary novel, Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse (also based on memories of his idyllic youthful relationship with Mme de Warens). Sophie was the cousin and houseguest of Rousseau's patroness and landlady Madame d'Épinay, whom he treated rather highhandedly. He resented being at Mme. d'Épinay's beck and call and detested the insincere conversation and shallow atheism of the Encyclopedistes whom he met at her table. Wounded feelings gave rise to a bitter three-way quarrel between Rousseau and Madame d'Épinay; her lover, the journalist Grimm; and their mutual friend, Diderot, who took their side against Rousseau. Diderot later described Rousseau as being "false, vain as Satan, ungrateful, cruel, hypocritical, and wicked... He sucked ideas from me, used them himself, and then affected to despise me".

Rousseau's break with the Encyclopedistes coincided with the composition of his three major works, in all of which he emphasized his fervent belief in a spiritual origin of man's soul and the universe, in contradistinction to the materialism of Diderot, La Mettrie and D'Holbach. During this period, Rousseau enjoyed the support and patronage of Charles II François Frédéric de Montmorency-Luxembourg and the Prince de Conti, two of the richest and most powerful nobles in France. These men truly liked Rousseau and enjoyed his ability to converse on any subject, but they also used him as a way of getting back at Louis XV and the political faction surrounding his mistress, Madame de Pompadour. Even with them, however, Rousseau went too far, courting rejection when he criticized the practice of tax farming, in which some of them engaged.

Rousseau's 800-page novel of sentiment, Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse, was published in 1761 to immense success. The book's rhapsodic descriptions of the natural beauty of the Swiss countryside struck a chord in the public and may have helped spark the subsequent nineteenth-century craze for Alpine scenery. In 1762, Rousseau published Du Contrat Social, Principes du droit politique (in English, literally Of the Social Contract, Principles of Political Right) in April. Even his friend Antoine-Jacques Roustan felt impelled to write a polite rebuttal of the chapter on Civil Religion in the Social Contract, which implied that the concept of a Christian republic was paradoxical since Christianity taught submission rather than participation in public affairs. Rousseau helped Roustan find a publisher for the rebuttal.

Rousseau published Emile, or On Education in May. A famous section of Emile, "The Profession of Faith of a Savoyard Vicar", was intended to be a defense of religious belief. Rousseau's choice of a Catholic vicar of humble peasant background (plausibly based on a kindly prelate he had met as a teenager) as a spokesman for the defense of religion was in itself a daring innovation for the time. The vicar's creed was that of Socinianism (or Unitarianism as it is called today). Because it rejected original sin and divine revelation, both Protestant and Catholic authorities took offense.

Moreover, Rousseau advocated the opinion that, insofar as they lead people to virtue, all religions are equally worthy, and that people should therefore conform to the religion in which they have been brought up. This religious indifferentism caused Rousseau and his books to be banned from France and Geneva. He was condemned from the pulpit by the Archbishop of Paris, his books were burned and warrants were issued for his arrest. Former friends such as Jacob Vernes of Geneva could not accept his views, and wrote violent rebuttals.

A sympathetic observer, David Hume "professed no surprise when he learned that Rousseau's books were banned in Geneva and elsewhere". Rousseau, he wrote, "has not had the precaution to throw any veil over his sentiments; and, as he scorns to dissemble his contempt for established opinions, he could not wonder that all the zealots were in arms against him. The liberty of the press is not so secured in any country... as not to render such an open attack on popular prejudice somewhat dangerous."

Voltaire and Frederick the Great

After Rousseau's Emile had outraged the French parliament, an arrest order was issued by parliament against him, causing him to flee to Switzerland. Subsequently, when the Swiss authorities also proved unsympathetic to him—condemning both Emile, and also The Social Contract—Voltaire issued an invitation to Rousseau to come and reside with him, commenting that: "I shall always love the author of the 'Vicaire savoyard' whatever he has done, and whatever he may do...Let him come here [to Ferney]! He must come! I shall receive him with open arms. He shall be master here more than I. I shall treat him like my own son."

Rousseau later expressed regret that he had not replied to Voltaire's invitation. In July 1762, after Rousseau was informed that he could not continue to reside in Bern, d'Alembert advised him to move to the Principality of Neuchâtel, ruled by Frederick the Great of Prussia. Subsequently, Rousseau accepted an invitation to reside in Môtiers, fifteen miles from Neuchâtel. On 11 July 1762, Rousseau wrote to Frederick, describing how he had been driven from France, from Geneva, and from Bern; and seeking Frederick's protection. He also mentioned that he had criticized Frederick in the past and would continue to be critical of Frederick in the future, stating however: "Your Majesty may dispose of me as you like." Frederick, still in the middle of the Seven Years' War, then wrote to the local governor of Neuchatel, Marischal Keith who was a mutual friend of theirs:

We must succor this poor unfortunate. His only offense is to have strange opinions which he thinks are good ones. I will send a hundred crowns, from which you will be kind enough to give him as much as he needs. I think he will accept them in kind more readily than in cash. If we were not at war, if we were not ruined, I would build him a hermitage with a garden, where he could live as I believe our first fathers did...I think poor Rousseau has missed his vocation; he was obviously born to be a famous anchorite, a desert father, celebrated for his austerities and flagellations...I conclude that the morals of your savage are as pure as his mind is illogical.

Rousseau, touched by the help he received from Frederick, stated that from then onwards he took a keen interest in Frederick's activities. As the Seven Years' War was about to end, Rousseau wrote to Frederick again, thanking him for the help received and urging him to put an end to military activities and to endeavor to keep his subjects happy instead. Frederick made no known reply, but commented to Keith that Rousseau had given him a "scolding".

Fugitive

For more than two years (1762–1765) Rousseau lived at Môtiers, spending his time in reading and writing and meeting visitors such as James Boswell (December 1764). In the meantime, the local ministers had become aware of the apostasies in some of his writings, and resolved not to let him stay in the vicinity. The Neuchâtel Consistory summoned Rousseau to answer a charge of blasphemy. He wrote back asking to be excused due to his inability to sit for a long time due to his ailment. Subsequently, Rousseau's own pastor, Frédéric-Guillaume de Montmollin, started denouncing him publicly as the Antichrist. In one inflammatory sermon, Montmollin quoted Proverbs 15:8: "The sacrifice of the wicked is an abomination to the Lord, but the prayer of the upright is his delight"; this was interpreted by everyone to mean that Rousseau's taking communion was detested by the Lord. The ecclesiastical attacks inflamed the parishioners, who proceeded to pelt Rousseau with stones when he would go out for walks. Around midnight of 6–7 September 1765, stones were thrown at the house Rousseau was staying in, and some glass windows were shattered. When a local official, Martinet, arrived at Rousseau's residence he saw so many stones on the balcony that he exclaimed "My God, it's a quarry!" At this point, Rousseau's friends in Môtiers advised him to leave the town.

Since he wanted to remain in Switzerland, Rousseau decided to accept an offer to move to a tiny island, the Ile de St.-Pierre, having a solitary house. Although it was within the Canton of Bern, from where he had been expelled two years previously, he was informally assured that he could move into this island house without fear of arrest, and he did so (10 September 1765). Here, despite the remoteness of his retreat, visitors sought him out as a celebrity. However, on 17 October 1765, the Senate of Bern ordered Rousseau to leave the island and all Bernese territory within fifteen days. He replied, requesting permission to extend his stay, and offered to be incarcerated in any place within their jurisdiction with only a few books in his possession and permission to walk occasionally in a garden while living at his own expense. The Senate's response was to direct Rousseau to leave the island, and all Bernese territory, within twenty four hours. On 29 October 1765 he left the Ile de St.-Pierre and moved to Strasbourg. At this point:

He had invitations to Potsdam from Frederick, to Corsica from Paoli, to Lorraine from Saint-Lambert, to Amsterdam from Rey the publisher, and to England from David Hume.

He subsequently decided to accept Hume's invitation to go to England.

Back in Paris

On 9 December 1765, having secured a passport from the French government to come to Paris, Rousseau left Strasbourg for Paris where he arrived after a week, and lodged in a palace of his friend, the Prince of Conti. Here he met Hume, and also numerous friends, and well wishers, and became a very conspicuous figure in the city. At this time, Hume wrote:

It is impossible to express or imagine the enthusiasm of this nation in Rousseau's favor...No person ever so much enjoyed their attention...Voltaire and everybody else are quite eclipsed.

One significant meeting could have taken place at this time: Diderot wanted to reconcile and make amends with Rousseau. However, both Diderot and Rousseau wanted the other person to take the initiative, so the two did not meet.

Letter of Walpole

On 1 January 1766, Grimm wrote a report to his clientele, in which he included a letter said to have been written by Frederick the Great to Rousseau. This letter had actually been composed by Horace Walpole as a playful hoax. Walpole had never met Rousseau, but he was well acquainted with Diderot and Grimm. The letter soon found wide publicity; Hume is believed to have been present, and to have participated in its creation. On 16 February 1766, Hume wrote to the Marquise de Brabantane: "The only pleasantry I permitted myself in connection with the pretended letter of the King of Prussia was made by me at the dinner table of Lord Ossory." This letter was one of the reasons for the later rupture in Hume's relations with Rousseau.

In Britain

On 4 January 1766 Rousseau left Paris along with Hume, the merchant De Luze (an old friend of Rousseau), and Rousseau's pet dog Sultan. After a four-day journey to Calais, where they stayed for two nights, the travelers embarked on a ship to Dover. On 13 January 1766 they arrived in London. Soon after their arrival, David Garrick arranged a box at the Drury Lane Theatre for Hume and Rousseau on a night when the King and Queen also attended. Garrick was himself performing in a comedy by himself, and also in a tragedy by Voltaire. Rousseau became so excited during the performance that he leaned too far and almost fell out of the box; Hume observed that the King and Queen were looking at Rousseau more than at the performance. Afterwards, Garrick served supper for Rousseau, who commended Garrick's acting: "Sir, you have made me shed tears at your tragedy, and smile at your comedy, though I scarce understood a word of your language."

At this time, Hume had a favorable opinion of Rousseau; in a letter to Madame de Brabantane, Hume wrote that after observing Rousseau carefully he had concluded that he had never met a more affable and virtuous person. According to Hume, Rousseau was "gentle, modest, affectionate, disinterested, of extreme sensitivity". Initially, Hume lodged Rousseau in the house of Madam Adams in London, but Rousseau began receiving so many visitors that he soon wanted to move to a quieter location. An offer came to lodge him in a Welsh monastery, and he was inclined to accept it, but Hume persuaded him to move to Chiswick. Rousseau now asked for Thérèse to rejoin him.

Meanwhile, James Boswell, then in Paris, offered to escort Thérèse to Rousseau. (Boswell had earlier met Rousseau and Thérèse at Motiers; he had subsequently also sent Thérèse a garnet necklace and had written to Rousseau seeking permission to occasionally communicate with her.) Hume foresaw what was going to happen: "I dread some event fatal to our friend's honor." Boswell and Thérèse were together for more than a week, and as per notes in Boswell's diary they consummated the relationship, having intercourse several times. On one occasion, Thérèse told Boswell: "Don't imagine you are a better lover than Rousseau."

Since Rousseau was keen to relocate to a more remote location, Richard Davenport—a wealthy and elderly widower who spoke French—offered to accommodate Thérèse and Rousseau at Wootton Hall in Staffordshire. On 22 March 1766 Rousseau and Thérèse set forth for Wootton, against Hume's advice. Hume and Rousseau would never meet again. Initially Rousseau liked his new accommodation at Wootton Hall, and wrote favorably about the natural beauty of the place, and how he was feeling reborn, forgetting past sorrows.

Quarrel with Hume

On 3 April 1766 a daily newspaper published the letter constituting Horace Walpole's hoax on Rousseau - without mentioning Walpole as the actual author; that the editor of the publication was Hume's personal friend compounded Rousseau's grief. Gradually articles critical of Rousseau started appearing in the British press; Rousseau felt that Hume, as his host, ought to have defended him. Moreover, in Rousseau's estimate, some of the public criticism contained details to which only Hume was privy. Further, Rousseau was aggrieved to find that Hume had been lodging in London with François Tronchin, son of Rousseau's enemy in Geneva.

About this time, Voltaire anonymously published his Letter to Dr. J.-J. Pansophe in which he gave extracts from many of Rousseau's prior statements which were critical of life in England; the most damaging portions of Voltaire's writeup were reprinted in a London periodical. Rousseau now decided that there was a conspiracy afoot to defame him. A further cause for Rousseau's displeasure was his concern that Hume might be tampering with his mail. The misunderstanding had arisen because Rousseau tired of receiving voluminous correspondence whose postage he had to pay. Hume offered to open Rousseau's mail himself and to forward the important letters to Rousseau; this offer was accepted. However, there is some evidence of Hume intercepting even Rousseau's outgoing mail.

After some correspondence with Rousseau, which included an eighteen-page letter from Rousseau describing the reasons for his resentment, Hume concluded that Rousseau was losing his mental balance. On learning that Rousseau had denounced him to his Parisian friends, Hume sent a copy of Rousseau's long letter to Madame de Boufflers. She replied stating that, in her estimate, Hume's alleged participation in the composition of Horace Walpole's faux letter was the reason for Rousseau's anger.

When Hume learnt that Rousseau was writing the Confessions, he assumed that the present dispute would feature in the book. Adam Smith, Turgot, Marischal Keith, Horace Walpole, and Mme de Boufflers advised Hume not to make his quarrel with Rousseau public; however, many members of d'Holbach's coterie—particularly, d'Alembert—urged him to reveal his version of the events. In October 1766 Hume's version of the quarrel was translated into French and published in France; in November it was published in England. Grimm included it in his correspondance; ultimately,

the quarrel resounded in Geneva, Amsterdam, Berlin, and St. Petersburg. A dozen pamphlets redoubled the bruit. Walpole printed his version of the dispute; Boswell attacked Walpole; Mme. de La Tour's Precis sur M. Rousseau called Hume a traitor; Voltaire sent him additional material on Rousseau's faults and crimes, on his frequentation of "places of ill fame", and on his seditious activities in Switzerland. George III "followed the battle with intense curiosity".

After the dispute became public, due in part to comments from notable publishers like Andrew Millar, Walpole told Hume that quarrels such as this only end up becoming a source of amusement for Europe. Diderot took a charitable view of the mess: "I knew these two philosophers well. I could write a play about them that would make you weep, and it would excuse them both." Amidst the controversy surrounding his quarrel with Hume, Rousseau maintained a public silence; but he resolved now to return to France. To encourage him to do so swiftly, Thérèse advised him that the servants at Wootton Hall sought to poison him. On 22 May 1767 Rousseau and Thérèse embarked from Dover for Calais.

In Grenoble

On 22 May 1767, Rousseau reentered France even though an arrest warrant against him was still in place. He had taken an assumed name, but was recognized, and a banquet in his honor was held by the city of Amiens. French nobles offered him a residence at this time. Initially, Rousseau decided to stay in an estate near Paris belonging to Mirabeau. Subsequently, on 21 June 1767, he moved to a chateau of the Prince of Conti in Trie.

Around this time, Rousseau started developing feelings of paranoia, anxiety, and of a conspiracy against him. Most of this was just his imagination at work, but on 29 January 1768, the theatre at Geneva was destroyed through burning, and Voltaire mendaciously accused Rousseau of being the culprit. In June 1768, Rousseau left Trie, leaving Therese behind, and went first to Lyon, and subsequently to Bourgoin. He now invited Therese to this place and married her, under his alias "Renou" in a faux civil ceremony in Bourgoin on 30 August 1768.

In January 1769, Rousseau and Thérèse went to live in a farmhouse near Grenoble. Here he practiced botany and completed the Confessions. At this time he expressed regret for placing his children in an orphanage. On 10 April 1770, Rousseau and Therese left for Lyon where he befriended Horace Coignet, a fabric designer and amateur musician. At Rousseau's suggestion, Coignet composed musical interludes for Rousseau's prose poem Pygmalion; this was performed in Lyon together with Rousseau's romance The Village Soothsayer to public acclaim. On 8 June, Rousseau and Therese left Lyon for Paris; they reached Paris on 24 June.

In Paris, Rousseau and Therese lodged in an unfashionable neighborhood of the city, the Rue Platrière—now called the Rue Jean-Jacques Rousseau. He now supported himself financially by copying music, and continued his study of botany. At this time also, he wrote his Letters on the Elements of Botany. These consisted of a series of letters Rousseau wrote to Mme Delessert in Lyon to help her daughters learn the subject. These letters received widespread acclaim when they were eventually published posthumously. "It's a true pedagogical model, and it complements Emile," commented Goethe.

For defending his reputation against hostile gossip, Rousseau had begun writing the Confessions in 1765. In November 1770, these were completed, and although he did not wish to publish them at this time, he began to offer group readings of certain portions of the book. Between December 1770, and May 1771, Rousseau made at least four group readings of his book with the final reading lasting seventeen hours. A witness to one of these sessions, Claude Joseph Dorat, wrote:

I expected a session of seven or eight hours; it lasted fourteen or fifteen. ... The writing is truly a phenomenon of genius, of simplicity, candor, and courage. How many giants reduced to dwarves! How many obscure but virtuous men restored to their rights and avenged against the wicked by the sole testimony of an honest man!

After May 1771, there were no more group readings because Madame d'Épinay wrote to the chief of police, who was her friend, to put a stop to Rousseau's readings so as to safeguard her privacy. The police called on Rousseau, who agreed to stop the readings. The Confessions were finally published posthumously in 1782.

In 1772, Rousseau was invited to present recommendations for a new constitution for the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, resulting in the Considerations on the Government of Poland, which was to be his last major political work.

Also in 1772, Rousseau began writing his Dialogues: Rousseau, Judge of Jean-Jacques, which was another attempt to reply to his critics. He completed writing it in 1776. The book is in the form of three dialogues between two characters; a Frenchman and Rousseau who argue about the merits and demerits of a third character—an author called Jean-Jacques. It has been described as his most unreadable work; in the foreword to the book, Rousseau admits that it may be repetitious and disorderly, but he begs the reader's indulgence on the grounds that he needs to defend his reputation from slander before he dies.

Final years

In 1766, Rousseau had impressed Hume with his physical prowess by spending ten hours at night on the deck in severe weather during the journey by ship from Calais to Dover while Hume was confined to his bunk. "When all the seamen were almost frozen to death...he caught no harm...He is one of the most robust men I have ever known," Hume noted. By 1770, Rousseau's urinary disease had also been greatly alleviated after he stopped listening to the advice of doctors. At that time, notes Damrosch, it was often better to let nature take its own course rather than subject oneself to medical procedures. His general health had also improved. However, on 24 October 1776, as he was walking on a narrow street in Paris a nobleman's carriage came rushing by from the opposite direction; flanking the carriage was a galloping Great Dane belonging to the nobleman. Rousseau was unable to dodge both the carriage and the dog, and was knocked down by the Great Dane. He seems to have suffered a concussion and neurological damage. His health began to decline; Rousseau's friend Corancez described the appearance of certain symptoms which indicate that Rousseau started suffering from epileptic seizures after the accident.

In 1777, Rousseau received a royal visitor, when the Holy Roman Emperor Joseph II came to meet him. His free entry to the Opera had been renewed by this time and he would go there occasionally. At this time also (1777–78), he composed one of his finest works, Reveries of a Solitary Walker.

In the spring of 1778, the Marquis Girardin invited Rousseau to live in a cottage in his château at Ermenonville. Rousseau and Thérèse went there on 20 May. Rousseau spent his time at the château in collecting botanical specimens, and teaching botany to Girardin's son. He ordered books from Paris on grasses, mosses and mushrooms, and made plans to complete his unfinished Emile and Sophie and Daphnis and Chloe.

On 1 July, a visitor commented that "men are wicked", to which Rousseau replied with "men are wicked, yes, but man is good"; in the evening there was a concert in the château in which Rousseau played on the piano his own composition of the Willow Song from Othello. On this day also, he had a hearty meal with Girardin's family; the next morning, as he was about to go teach music to Girardin's daughter, he died of cerebral bleeding resulting in an apoplectic stroke. It is now believed that repeated falls, including the accident involving the Great Dane, may have contributed to Rousseau's stroke.

Following his death, Grimm, Madame de Staël and others spread the false news that Rousseau had committed suicide; according to other gossip, Rousseau was insane when he died. All those who met him in his last days agree that he was in a serene frame of mind at this time.

On 4 July 1778, Rousseau was buried on the Île des Peupliers, which became a place of pilgrimage for his many admirers. On 11 October 1794, his remains were moved to the Panthéon, where they were placed near the remains of Voltaire.

Philosophy

Rousseau based his political philosophy on contract theory and his reading of Hobbes.

Theory of human nature

The first man who, having fenced in a piece of land, said 'This is mine', and found people naïve enough to believe him, that man was the true founder of civil society. From how many crimes, wars, and murders, from how many horrors and misfortunes might not any one have saved mankind, by pulling up the stakes, or filling up the ditch, and crying to his fellows: Beware of listening to this impostor; you are undone if you once forget that the fruits of the earth belong to us all, and the earth itself to nobody.

In common with other philosophers of the day, Rousseau looked to a hypothetical "state of nature" as a normative guide.

Rousseau criticized Thomas Hobbes for asserting that since man in the "state of nature... has no idea of goodness he must be naturally wicked; that he is vicious because he does not know virtue". On the contrary, Rousseau holds that "uncorrupted morals" prevail in the "state of nature" and he especially praised the admirable moderation of the Caribbeans in expressing the sexual urge despite the fact that they live in a hot climate, which "always seems to inflame the passions".

Rousseau asserted that the stage of human development associated with what he called "savages" was the best or optimal in human development, between the less-than-optimal extreme of brute animals on the one hand and the extreme of decadent civilization on the other. "...[N]othing is so gentle as man in his primitive state, when placed by nature at an equal distance from the stupidity of brutes and the fatal enlightenment of civil man". Referring to the stage of human development which Rousseau associates with savages, Rousseau writes:

"Hence although men had become less forbearing, and although natural pity had already undergone some alteration, this period of the development of human faculties, maintaining a middle position between the indolence of our primitive state and the petulant activity of our egocentrism, must have been the happiest and most durable epoch. The more one reflects on it, the more one finds that this state was the least subject to upheavals and the best for man, and that he must have left it only by virtue of some fatal chance happening that, for the common good, ought never to have happened. The example of savages, almost all of whom have been found in this state, seems to confirm that the human race had been made to remain in it always; that this state is the veritable youth of the world; and that all the subsequent progress has been in appearance so many steps toward the perfection of the individual, and in fact toward the decay of the species."

The perspective of many of today's environmentalists can be traced back to Rousseau who believed that the more men deviated from the state of nature, the worse off they would be. Espousing the belief that all degenerates in men's hands, Rousseau taught that men would be free, wise, and good in the state of nature and that instinct and emotion, when not distorted by the unnatural limitations of civilization, are nature's voices and instructions to the good life. Rousseau's "noble savage" stands in direct opposition to the man of culture.

Stages of human development

Rousseau believed that the savage stage was not the first stage of human development, but the third stage. Rousseau held that this third savage stage of human societal development was an optimum, between the extreme of the state of brute animals and animal-like "ape-men" on the one hand and the extreme of decadent civilized life on the other. This has led some critics to attribute to Rousseau the invention of the idea of the noble savage, which Arthur Lovejoy conclusively showed misrepresents Rousseau's thought. Rousseau's view was that morality was not embued by society, but rather "natural" in the sense of "innate". It could be seen as an outgrowth from man's instinctive disinclination to witness suffering, from which arise emotions of compassion or empathy. These are sentiments shared with animals, and whose existence even Hobbes acknowledged.

Rousseau's ideas of human development were highly interconnected with forms of mediation, or the processes that individual humans use to interact with themselves and others while using an alternate perspective or thought process. According to Rousseau, these were developed through the innate perfectibility of humanity. These include a sense of self, morality, pity, and imagination. Rousseau's writings are purposely ambiguous concerning the formation of these processes to the point that mediation is always intrinsically part of humanity's development. An example of this is the notion that as an individual, one needs an alternative perspective to come to the realization that they are a 'self'.

In Rousseau's philosophy, society's negative influence on men centers on its transformation of amour de soi, a positive self-love, into amour-propre, or pride. Amour de soi represents the instinctive human desire for self-preservation, combined with the human power of reason. In contrast, amour-propre is artificial and encourages man to compare himself to others, thus creating unwarranted fear and allowing men to take pleasure in the pain or weakness of others. Rousseau was not the first to make this distinction. It had been invoked by Vauvenargues, among others.

In the Discourse on the Arts and Sciences Rousseau argues that the arts and sciences have not been beneficial to humankind, because they arose not from authentic human needs but rather as a result of pride and vanity. Moreover, the opportunities they create for idleness and luxury have contributed to the corruption of man. He proposed that the progress of knowledge had made governments more powerful and had crushed individual liberty; and he concluded that material progress had actually undermined the possibility of true friendship by replacing it with jealousy, fear, and suspicion.

In contrast to the optimistic view of other Enlightenment figures, for Rousseau, progress has been inimical to the well-being of humanity, that is, unless it can be counteracted by the cultivation of civic morality and duty. Only in civil society can man be ennobled—through the use of reason:

The passage from the state of nature to the civil state produces a very remarkable change in man, by substituting justice for instinct in his conduct, and giving his actions the morality they had formerly lacked. Then only, when the voice of duty takes the place of physical impulses and right of appetite, does man, who so far had considered only himself, find that he is forced to act on different principles, and to consult his reason before listening to his inclinations. Although in this state he deprives himself of some advantages which he got from nature, he gains in return others so great, his faculties are so stimulated and developed, his ideas so extended, his feelings so ennobled, and his whole soul so uplifted, that, did not the abuses of this new condition often degrade him below that which he left, he would be bound to bless continually the happy moment which took him from it for ever, and, instead of a stupid and unimaginative animal, made him an intelligent being and a man.

Society corrupts men only insofar as the Social Contract has not de facto succeeded, as we see in contemporary society as described in the Discourse on Inequality (1754). In this essay, which elaborates on the ideas introduced in the Discourse on the Arts and Sciences, Rousseau traces man's social evolution from a primitive state of nature to modern society. The earliest solitary humans possessed a basic drive for self-preservation and a natural disposition to compassion or pity. They differed from animals, however, in their capacity for free will and their potential perfectibility. As they began to live in groups and form clans they also began to experience family love, which Rousseau saw as the source of the greatest happiness known to humanity.

As long as differences in wealth and status among families were minimal, the first coming together in groups was accompanied by a fleeting golden age of human flourishing. The development of agriculture, metallurgy, private property, and the division of labour and resulting dependency on one another, however, led to economic inequality and conflict. As population pressures forced them to associate more and more closely, they underwent a psychological transformation: they began to see themselves through the eyes of others and came to value the good opinion of others as essential to their self-esteem.

Rousseau posits that the original, deeply flawed social contract (i.e., that of Hobbes), which led to the modern state, was made at the suggestion of the rich and powerful, who tricked the general population into surrendering their liberties to them and instituted inequality as a fundamental feature of human society. Rousseau's own conception of the Social Contract can be understood as an alternative to this fraudulent form of association.

At the end of the Discourse on Inequality, Rousseau explains how the desire to have value in the eyes of others comes to undermine personal integrity and authenticity in a society marked by interdependence, and hierarchy. In the last chapter of the Social Contract, Rousseau would ask 'What is to be done?' He answers that now all men can do is to cultivate virtue in themselves and submit to their lawful rulers. To his readers, however, the inescapable conclusion was that a new and more equitable Social Contract was needed.

Like other Enlightenment philosophers, Rousseau was critical of the Atlantic slave trade.

Political theory

The Social Contract outlines the basis for a legitimate political order within a framework of classical republicanism. Published in 1762, it became one of the most influential works of political philosophy in the Western tradition. It developed some of the ideas mentioned in an earlier work, the article Économie Politique (Discourse on Political Economy), featured in Diderot's Encyclopédie. The treatise begins with the dramatic opening lines, "Man is born free, and everywhere he is in chains. Those who think themselves the masters of others are indeed greater slaves than they."

Rousseau claimed that the state of nature was a primitive condition without law or morality, which human beings left for the benefits and necessity of cooperation. As society developed, the division of labor and private property required the human race to adopt institutions of law. In the degenerate phase of society, man is prone to be in frequent competition with his fellow men while also becoming increasingly dependent on them. This double pressure threatens both his survival and his freedom.

According to Rousseau, by joining together into civil society through the social contract and abandoning their claims of natural right, individuals can both preserve themselves and remain free. This is because submission to the authority of the general will of the people as a whole guarantees individuals against being subordinated to the wills of others and also ensures that they obey themselves because they are, collectively, the authors of the law.

Although Rousseau argues that sovereignty (or the power to make the laws) should be in the hands of the people, he also makes a sharp distinction between the sovereign and the government. The government is composed of magistrates, charged with implementing and enforcing the general will. The "sovereign" is the rule of law, ideally decided on by direct democracy in an assembly.

Rousseau opposed the idea that the people should exercise sovereignty via a representative assembly (Book III, Chapter XV). He approved the kind of republican government of the city-state, for which Geneva provided a model—or would have done if renewed on Rousseau's principles. France could not meet Rousseau's criterion of an ideal state because it was too big. Much subsequent controversy about Rousseau's work has hinged on disagreements concerning his claims that citizens constrained to obey the general will are thereby rendered free:

The notion of the general will is wholly central to Rousseau's theory of political legitimacy. ... It is, however, an unfortunately obscure and controversial notion. Some commentators see it as no more than the dictatorship of the proletariat or the tyranny of the urban poor (such as may perhaps be seen in the French Revolution). Such was not Rousseau's meaning. This is clear from the Discourse on Political Economy, where Rousseau emphasizes that the general will exists to protect individuals against the mass, not to require them to be sacrificed to it. He is, of course, sharply aware that men have selfish and sectional interests which will lead them to try to oppress others. It is for this reason that loyalty to the good of all alike must be a supreme (although not exclusive) commitment by everyone, not only if a truly general will is to be heeded but also if it is to be formulated successfully in the first place".

A remarkable peculiarity of Social Contract is its logical rigor that Rousseau has learned in his twenties from mathematics:

Rousseau develops his theory in an almost mathematical manner, deriving statements from the initial thesis that man must keep close to nature. The ‘natural’ state, with its original liberty and equality, is hindered by man’s ‘unnatural’ involvement in collective activities resulting in inequality which, in turn, infringes on liberty. The purpose of this social contract, which is a kind of tacit agreement, is simply to guarantee equality and, consequently, liberty as the superior social values... A number of political statements, particularly about the organization of powers, are derived from the ‘axioms’ of equality among citizens and their subordination to the general will.

— Andranik Tangian (2014) Mathematical Theory of Democracy

The logical framework of Social Contract is also analyzed in.

Education and child rearing

The noblest work in education is to make a reasoning man, and we expect to train a young child by making him reason! This is beginning at the end; this is making an instrument of a result. If children understood how to reason they would not need to be educated.

— Rousseau, Emile, p. 52

Rousseau's philosophy of education concerns itself not with particular techniques of imparting information and concepts, but rather with developing the pupil's character and moral sense, so that he may learn to practice self-mastery and remain virtuous even in the unnatural and imperfect society in which he will have to live. The hypothetical boy, Émile, is to be raised in the countryside, which, Rousseau believes, is a more natural and healthy environment than the city, under the guardianship of a tutor who will guide him through various learning experiences arranged by the tutor. Today we would call this the disciplinary method of "natural consequences". Rousseau felt that children learn right and wrong through experiencing the consequences of their acts rather than through physical punishment. The tutor will make sure that no harm results to Émile through his learning experiences.

Rousseau became an early advocate of developmentally appropriate education; his description of the stages of child development mirrors his conception of the evolution of culture. He divides childhood into stages:

- the first to the age of about 12, when children are guided by their emotions and impulses

- during the second stage, from 12 to about 16, reason starts to develop

- finally the third stage, from the age of 16 onwards, when the child develops into an adult

Rousseau recommends that the young adult learn a manual skill such as carpentry, which requires creativity and thought, will keep him out of trouble, and will supply a fallback means of making a living in the event of a change of fortune (the most illustrious aristocratic youth to have been educated this way may have been Louis XVI, whose parents had him learn the skill of locksmithing). The sixteen-year-old is also ready to have a companion of the opposite sex.

Although his ideas foreshadowed modern ones in many ways, in one way they do not: Rousseau was a believer in the moral superiority of the patriarchal family on the antique Roman model. Sophie, the young woman Émile is destined to marry, as his representative of ideal womanhood, is educated to be governed by her husband while Émile, as his representative of the ideal man, is educated to be self-governing. This is not an accidental feature of Rousseau's educational and political philosophy; it is essential to his account of the distinction between private, personal relations and the public world of political relations. The private sphere as Rousseau imagines it depends on the subordination of women, for both it and the public political sphere (upon which it depends) to function as Rousseau imagines it could and should. Rousseau anticipated the modern idea of the bourgeois nuclear family, with the mother at home taking responsibility for the household and for childcare and early education.

Feminists, beginning in the late 18th century with Mary Wollstonecraft in 1792, have criticized Rousseau for his confinement of women to the domestic sphere—unless women were domesticated and constrained by modesty and shame, he feared "men would be tyrannized by women ... For, given the ease with which women arouse men's senses—men would finally be their victims ..." His contemporaries saw it differently because Rousseau thought that mothers should breastfeed their children. Marmontel wrote that his wife thought, "One must forgive something," she said, "in one who has taught us to be mothers."

Rousseau's ideas have influenced progressive "child-centered" education. John Darling's 1994 book Child-Centered Education and its Critics portrays the history of modern educational theory as a series of footnotes to Rousseau, a development he regards as bad. The theories of educators such as Rousseau's near contemporaries Pestalozzi, Mme. de Genlis and, later, Maria Montessori and John Dewey, which have directly influenced modern educational practices, have significant points in common with those of Rousseau.

Religion

Having converted to Roman Catholicism early in life and returned to the austere Calvinism of his native Geneva as part of his period of moral reform, Rousseau maintained a profession of that religious philosophy and of John Calvin as a modern lawgiver throughout the remainder of his life. Unlike many of the more agnostic Enlightenment philosophers, Rousseau affirmed the necessity of religion. His views on religion presented in his works of philosophy, however, may strike some as discordant with the doctrines of both Catholicism and Calvinism.

Rousseau's strong endorsement of religious toleration, as expounded in Émile, was interpreted as advocating indifferentism, a heresy, and led to the condemnation of the book in both Calvinist Geneva and Catholic Paris. Although he praised the Bible, he was disgusted by the Christianity of his day. Rousseau's assertion in The Social Contract that true followers of Christ would not make good citizens may have been another reason for his condemnation in Geneva. He also repudiated the doctrine of original sin, which plays a large part in Calvinism. In his "Letter to Beaumont", Rousseau wrote, "there is no original perversity in the human heart."

In the 18th century, many deists viewed God merely as an abstract and impersonal creator of the universe, likened to a giant machine. Rousseau's deism differed from the usual kind in its emotionality. He saw the presence of God in the creation as good, and separate from the harmful influence of society. Rousseau's attribution of a spiritual value to the beauty of nature anticipates the attitudes of 19th-century Romanticism towards nature and religion. (Historians—notably William Everdell, Graeme Garrard, and Darrin McMahon—have additionally situated Rousseau within the Counter-Enlightenment.) Rousseau was upset that his deism was so forcefully condemned, while those of the more atheistic philosophers were ignored. He defended himself against critics of his religious views in his "Letter to Mgr de Beaumont, the Archbishop of Paris", "in which he insists that freedom of discussion in religious matters is essentially more religious than the attempt to impose belief by force."

Legacy

Jean-Jacques, aime ton pays [love your country], showing Rousseau's father gesturing towards the window. The scene is drawn from a footnote to the Letter to d'Alembert where Rousseau recalls witnessing the popular celebrations following the exercises of the St Gervais regiment.

General will

Rousseau's idea of the volonté générale ("general will") was not original with him but rather belonged to a well-established technical vocabulary of juridical and theological writings in use at the time. The phrase was used by Diderot and also by Montesquieu (and by his teacher, the Oratorian friar Nicolas Malebranche). It served to designate the common interest embodied in legal tradition, as distinct from and transcending people's private and particular interests at any particular time. It displayed a rather democratic ideology, as it declared that the citizens of a given nation should carry out whatever actions they deem necessary in their own sovereign assembly.

The concept was also an important aspect of the more radical 17th-century republican tradition of Spinoza, from whom Rousseau differed in important respects, but not in his insistence on the importance of equality:

While Rousseau's notion of the progressive moral degeneration of mankind from the moment civil society established itself diverges markedly from Spinoza's claim that human nature is always and everywhere the same ... for both philosophers the pristine equality of the state of nature is our ultimate goal and criterion ... in shaping the "common good", volonté générale, or Spinoza's mens una, which alone can ensure stability and political salvation. Without the supreme criterion of equality, the general will would indeed be meaningless. ... When in the depths of the French Revolution the Jacobin clubs all over France regularly deployed Rousseau when demanding radical reforms. and especially anything—such as land redistribution—designed to enhance equality, they were at the same time, albeit unconsciously, invoking a radical tradition which reached back to the late seventeenth century.

French Revolution

Robespierre and Saint-Just, during the Reign of Terror, regarded themselves to be principled egalitarian republicans, obliged to do away with superfluities and corruption; in this they were inspired most prominently by Rousseau. According to Robespierre, the deficiencies in individuals were rectified by upholding the 'common good' which he conceptualized as the collective will of the people; this idea was derived from Rousseau's General Will. The revolutionaries were also inspired by Rousseau to introduce Deism as the new official civil religion of France:

Ceremonial and symbolic occurrences of the more radical phases of the Revolution invoked Rousseau and his core ideas. Thus the ceremony held at the site of the demolished Bastille, organized by the foremost artistic director of the Revolution, Jacques-Louis David, in August 1793 to mark the inauguration of the new republican constitution, an event coming shortly after the final abolition of all forms of feudal privilege, featured a cantata based on Rousseau's democratic pantheistic deism as expounded in the celebrated "Profession de foi d'un vicaire savoyard" in book four of Émile.

Rousseau's influence on the French Revolution was noted by Edmund Burke, who critiqued Rousseau in "Reflections on the Revolution in France," and this critique reverberated throughout Europe, leading Catherine the Great to ban his works. This connection between Rousseau and the French Revolution (especially the Terror) persisted through the next century. As François Furet notes that "we can see that for the whole of the nineteenth century Rousseau was at the heart of the interpretation of the Revolution for both its admirers and its critics."

Effect on the American Revolution

According to some scholars, Rousseau exercised minimal influence on the Founding Fathers of the United States, despite similarities between their ideas. They shared beliefs regarding the self-evidence that "all men are created equal," and the conviction that citizens of a republic be educated at public expense. A parallel can be drawn between the United States Constitution's concept of the "general welfare" and Rousseau's concept of the "general will". Further commonalities exist between Jeffersonian democracy and Rousseau's praise of Switzerland and Corsica's economies of isolated and independent homesteads, and his endorsement of a well-regulated militia, such as those of the Swiss cantons.

However, Will and Ariel Durant have opined that Rousseau had a definite political influence on America. According to them:

The first sign of [Rousseau's] political influence was in the wave of public sympathy that supported active French aid to the American Revolution. Jefferson derived the Declaration of Independence from Rousseau as well as from Locke and Montesquieu. As ambassador to France (1785–89) he absorbed much from both Voltaire and Rousseau...The success of the American Revolution raised the prestige of Rousseau's philosophy.

One of Rousseau's most important American followers was textbook writer Noah Webster (1758–1843), who was influenced by Rousseau's ideas on pedagogy in Emile (1762). Webster structured his Speller in accord with Rousseau's ideas about the stages of a child's intellectual development.

Rousseau's writings perhaps had an indirect influence on American literature through the writings of Wordsworth and Kant, whose works were important to the New England transcendentalist Ralph Waldo Emerson, as well as on Unitarians such as theologian William Ellery Channing. The Last of the Mohicans and other American novels reflect republican and egalitarian ideals present alike in Thomas Paine and in English Romantic primitivism.

Criticisms of Rousseau

The first to criticize Rousseau were his fellow Philosophes, above all, Voltaire. According to Jacques Barzun, Voltaire was annoyed by the first discourse, and outraged by the second. Voltaire's reading of the second discourse was that Rousseau would like the reader to "walk on all fours" befitting a savage.

Samuel Johnson told his biographer James Boswell, "I think him one of the worst of men; a rascal, who ought to be hunted out of society, as he has been".

Jean-Baptiste Blanchard was his leading Catholic opponent. Blanchard rejects Rousseau's negative education, in which one must wait until a child has grown to develop reason. The child would find more benefit from learning in his earliest years. He also disagreed with his ideas about female education, declaring that women are a dependent lot. So removing them from their motherly path is unnatural, as it would lead to the unhappiness of both men and women.

Historian Jacques Barzun states that, contrary to myth, Rousseau was no primitivist; for him:

The model man is the independent farmer, free of superiors and self-governing. This was cause enough for the philosophes' hatred of their former friend. Rousseau's unforgivable crime was his rejection of the graces and luxuries of civilized existence. Voltaire had sung "The superfluous, that most necessary thing." For the high bourgeois standard of living Rousseau would substitute the middling peasant's. It was the country versus the city—an exasperating idea for them, as was the amazing fact that every new work of Rousseau's was a huge success, whether the subject was politics, theater, education, religion, or a novel about love.

As early as 1788, Madame de Staël published her Letters on the works and character of J.-J. Rousseau. In 1819, in his famous speech "On Ancient and Modern Liberty", the political philosopher Benjamin Constant, a proponent of constitutional monarchy and representative democracy, criticized Rousseau, or rather his more radical followers (specifically the Abbé de Mably), for allegedly believing that "everything should give way to collective will, and that all restrictions on individual rights would be amply compensated by participation in social power."

Frédéric Bastiat severely criticized Rousseau in several of his works, most notably in "The Law", in which, after analyzing Rousseau's own passages, he stated that:

And what part do persons play in all this? They are merely the machine that is set in motion. In fact, are they not merely considered to be the raw material of which the machine is made? Thus the same relationship exists between the legislator and the prince as exists between the agricultural expert and the farmer; and the relationship between the prince and his subjects is the same as that between the farmer and his land. How high above mankind, then, has this writer on public affairs been placed?

Bastiat believed that Rousseau wished to ignore forms of social order created by the people—viewing them as a thoughtless mass to be shaped by philosophers. Bastiat, who is considered by thinkers associated with the Austrian School of Economics to be one of the precursors of the "spontaneous order", presented his own vision of what he considered to be the "Natural Order" in a simple economic chain in which multiple parties might interact without necessarily even knowing each other, cooperating and fulfilling each other's needs in accordance with basic economic laws such as supply and demand. In such a chain, to produce clothing, multiple parties have to act independently—e.g. farmers to fertilize and cultivate land to produce fodder for the sheep, people to shear them, transport the wool, turn it into cloth, and another to tailor and sell it. Those persons engage in economic exchange by nature, and don't need to be ordered to, nor do their efforts need to be centrally coordinated. Such chains are present in every branch of human activity, in which individuals produce or exchange goods and services, and together, naturally create a complex social order that does not require external inspiration, central coordination of efforts, or bureaucratic control to benefit society as a whole. This, according to Bastiat, is a proof that humanity itself is capable of creating a complex socioeconomic order that might be superior to an arbitrary vision of a philosopher.

Bastiat also believed that Rousseau contradicted himself when presenting his views concerning human nature; if nature is "sufficiently invincible to regain its empire", why then would it need philosophers to direct it back to a natural state? Conversely, he believed that humanity would choose what it would have without philosophers to guide it, in accordance with the laws of economy and human nature itself.[citation needed] Another point of criticism Bastiat raised was that living purely in nature would doom mankind to suffer unnecessary hardships.

The Marquis de Sade's Justine, or the Misfortunes of Virtue (1791) partially parodied and used as inspiration Rousseau's sociological and political concepts in the Discourse on Inequality and The Social Contract. Concepts such as the state of nature, civilization being the catalyst for corruption and evil, and humans "signing" a contract to mutually give up freedoms for the protection of rights, particularly referenced. The Comte de Gernande in Justine, for instance, after Thérèse asks him how he justifies abusing and torturing women, states:

The necessity mutually to render one another happy cannot legitimately exist save between two persons equally furnished with the capacity to do one another hurt and, consequently, between two persons of commensurate strength: such an association can never come into being unless a contract [un pacte] is immediately formed between these two persons, which obligates each to employ against each other no kind of force but what will not be injurious to either. . . [W]hat sort of a fool would the stronger have to be to subscribe to such an agreement?

Edmund Burke formed an unfavorable impression of Rousseau when the latter visited England with Hume and later drew a connection between Rousseau's egoistic philosophy and his personal vanity, saying Rousseau "entertained no principle... but vanity. With this vice he was possessed to a degree little short of madness".

Charles Dudley Warner wrote about Rousseau in his essay, Equality; "Rousseau borrowed from Hobbes as well as from Locke in his conception of popular sovereignty; but this was not his only lack of originality. His discourse on primitive society, his unscientific and unhistoric notions about the original condition of man, were those common in the middle of the eighteenth century."

In 1919, Irving Babbitt, founder of a movement called the "New Humanism", wrote a critique of what he called "sentimental humanitarianism", for which he blamed Rousseau. Babbitt's depiction of Rousseau was countered in a celebrated and much reprinted essay by A.O. Lovejoy in 1923. In France, fascist theorist Charles Maurras, founder of Action Française, "had no compunctions in laying the blame for both Romantisme et Révolution firmly on Rousseau in 1922."

During the Cold War, Rousseau was criticized for his association with nationalism and its attendant abuses, for example in Talmon, Jacob Leib (1952), The Origins of Totalitarian Democracy. This came to be known among scholars as the "totalitarian thesis". Political scientist J.S. Maloy states that "the twentieth century added Nazism and Stalinism to Jacobinism on the list of horrors for which Rousseau could be blamed. ... Rousseau was considered to have advocated just the sort of invasive tampering with human nature which the totalitarian regimes of mid-century had tried to instantiate." But he adds that "The totalitarian thesis in Rousseau studies has, by now, been discredited as an attribution of real historical influence." Arthur Melzer, however, while conceding that Rousseau would not have approved of modern nationalism, observes that his theories do contain the "seeds of nationalism", insofar as they set forth the "politics of identification", which are rooted in sympathetic emotion. Melzer also believes that in admitting that people's talents are unequal, Rousseau therefore tacitly condones the tyranny of the few over the many. Others counter, however, that Rousseau was concerned with the concept of equality under the law, not equality of talents.[citation needed] For Stephen T. Engel, on the other hand, Rousseau's nationalism anticipated modern theories of "imagined communities" that transcend social and religious divisions within states.

On similar grounds, one of Rousseau's strongest critics during the second half of the 20th century was political philosopher Hannah Arendt. Using Rousseau's thought as an example, Arendt identified the notion of sovereignty with that of the general will. According to her, it was this desire to establish a single, unified will based on the stifling of opinion in favor of public passion that contributed to the excesses of the French Revolution.

Appreciation and influence

The book Rousseau and Revolution, by Will and Ariel Durant, begins with the following words about Rousseau: