Jainism (/ˈdʒeɪnɪzəm/), traditionally known as Jain Dharma, is an ancient Indian religion and a major world religious group. It traces its spiritual ideas and history through a succession of twenty-four leaders or Tirthankaras, with the first in the current time cycle being Rishabhanatha, whom the tradition holds to have lived millions of years ago; the twenty-third tirthankara Parshvanatha, whom historians date to 9th century BCE; and the twenty-fourth tirthankara, Mahavira around 600 BCE. Jainism is considered to be an eternal dharma with the tirthankaras guiding every time cycle of the cosmology.

The main religious premises of the Jain dharma are ahiṃsā (non-violence), anekāntavāda (many-sidedness), aparigraha (non-attachment) and asceticism (abstinence from sensual pleasures). Devout Jains take five main vows: ahiṃsā (non-violence), satya (truth), asteya (not stealing), brahmacharya (sexual continence), and aparigraha (non-possessiveness). These principles have affected Jain culture in many ways, such as leading to a predominantly vegetarian lifestyle. Parasparopagraho jīvānām (the function of souls is to help one another) is the faith's motto and the Ṇamōkāra mantra is its most common and basic prayer.

Jainism is one of the world's oldest continuously-practiced religions. It has two major ancient sub-traditions, Digambaras and Śvētāmbaras, with different views on ascetic practices, gender and which texts can be considered canonical; both have mendicants supported by laypersons (śrāvakas and śrāvikas). The Śvētāmbara tradition in turn has three subtraditions: Mandirvāsī, Terapanthi and Sthānakavasī. The religion has between four and five million followers, known as Jains, who reside mostly in India. Outside India, some of the largest communities are in Canada, Europe, and the United States, with Japan hosting a fast-growing community of converts. Major festivals include Paryushana and Das Lakshana, Ashtanika, Mahavir Janma Kalyanak, Akshaya Tritiya, and Dipawali.

Beliefs and philosophy

Jainism is transtheistic and forecasts that the universe evolves without violating the law of substance dualism, auto executed through the middle ground between the principles of parallelism and interactionism.

Dravya (Substance)

Dravya means substances or entity in Sanskrit. According to Jain philosophy, the universe is made up of six eternal substances: sentient beings or souls (jīva), non-sentient substance or matter (pudgala), principle of motion (dharma), the principle of rest (adharma), space (ākāśa) and time (kāla). The latter five are united as the ajiva (the non-living). Jain philosophers distinguish a substance from a body, or thing, by declaring the former a simple indestructible element, while the latter is a compound, made of one or more substances, which can be destroyed.

Tattva (Reality)

Tattva connotes reality or truth in Jain philosophy, and is the framework for salvation. According to Digambara Jains, there are seven tattvas: the sentient (jiva)living; the insentient (ajiva)non-living; the karmic influx to the soul (Āsrava); mix of living and non living; bondage of karmic particles to the soul (Bandha); stoppage of karmic particles (Saṃvara); wiping away of past karmic particles (Nirjarā); and liberation (Moksha). Śvētāmbaras add two further tattvas, namely good karma (Punya) and bad karma (Paap). The true insight in Jain philosophy is considered as "faith in the tattvas". The spiritual goal in Jainism is to reach moksha for ascetics, but for most Jain laypersons it is to accumulate good karma that leads to better rebirth and a step closer to liberation.

Soul and karma

According to Jainism, the existence of "a bound and ever changing soul" is a self-evident truth, an axiom which does not need to be proven. It maintains that there are numerous souls, but every one of them has three qualities (Guṇa): consciousness (chaitanya, the most important), bliss (sukha) and vibrational energy (virya). It further claims that the vibration draws karmic particles to the soul and creates bondages, but is also what adds merit or demerit to the soul. Jain texts state that souls exist as "clothed with material bodies", where it entirely fills up the body. Karma, as in other Indian religions, connotes in Jainism the universal cause and effect law. However, it is envisioned as a material substance (subtle matter) that can bind to the soul, travel with the soul in bound form between rebirths, and affect the suffering and happiness experienced by the jiva in the lokas. Karma is believed to obscure and obstruct the innate nature and striving of the soul, as well as its spiritual potential in the next rebirth.

Saṃsāra

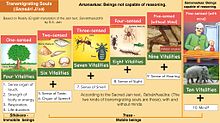

The conceptual framework of the Saṃsāra doctrine differs between Jainism and other Indian religions. Soul (jiva) is accepted as a truth, as in Hinduism but not Buddhism. The cycle of rebirths has a definite beginning and end in Jainism. Jain theosophy asserts that each soul passes through 8,400,000 birth-situations as they circle through Saṃsāra, going through five types of bodies: earth bodies, water bodies, fire bodies, air bodies and vegetable lives, constantly changing with all human and non-human activities from rainfall to breathing. Harming any life form is a sin in Jainism, with negative karmic effects. Jainism states that souls begin in a primordial state, and either evolve to a higher state or regress if driven by their karma. It further clarifies that abhavya (incapable) souls can never attain moksha (liberation). It explains that the abhavya state is entered after an intentional and shockingly evil act. Souls can be good or evil in Jainism, unlike the nondualism of some forms of Hinduism and Buddhism. According to Jainism, a Siddha (liberated soul) has gone beyond Saṃsāra, is at the apex, is omniscient, and remains there eternally.

Cosmology

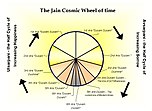

Jain texts propound that the universe consists of many eternal lokas (realms of existence). As in Buddhism and Hinduism, both time and the universe are eternal, but the universe is transient. The universe, body, matter and time are considered separate from the soul (jiva). Their interaction explains life, living, death and rebirth in Jain philosophy. The Jain cosmic universe has three parts, the upper, middle, and lower worlds (urdhva loka, madhya loka, and adho loka). Jainism states that Kāla (time) is without beginning and eternal; the cosmic wheel of time, kālachakra, rotates ceaselessly. In this part of the universe, it explains, there are six periods of time within two eons (ara), and in the first eon the universe generates, and in the next it degenerates. Thus, it divides the worldly cycle of time into two half-cycles, utsarpiṇī (ascending, progressive prosperity and happiness) and avasarpiṇī (descending, increasing sorrow and immorality). It states that the world is currently in the fifth ara of avasarpiṇī, full of sorrow and religious decline, where the height of living beings shrinks. According to Jainism, after the sixth ara, the universe will be reawakened in a new cycle.

God

Jainism is a transtheistic religion, holding that the universe was not created, and will exist forever. It is believed to be independent, having no creator, governor, judge, or destroyer. In this, it is unlike the Abrahamic religions, but similar to Buddhism. However, Jainism believes in the world of heavenly and hell beings who are born, die and are reborn like earthly beings. Jain texts maintain that souls who live happily in the body of a god do so because of their positive karma. It is further stated that they possess a more transcendent knowledge about material things and can anticipate events in the human realms. However, once their past karmic merit is exhausted, it is explained that their souls are reborn again as humans, animals or other beings. In Jainism, perfect souls with a body are called arihant (victors) and perfect souls without a body are called Siddhas (liberated souls).

Epistemology

Jain philosophy accepts three reliable means of knowledge (pramana). It holds that correct knowledge is based on perception (pratyaksa), inference (anumana) and testimony (sabda or the word of scriptures). These ideas are elaborated in Jain texts such as Tattvarthasūtra, Parvacanasara, Nandi and Anuyogadvarini. Some Jain texts add analogy (upamana) as the fourth reliable means, in a manner similar to epistemological theories found in other Indian religions. In Jainism, jnāna (knowledge) is said to be of five kinds – Kevala Jnana (Omniscience), Śrutu Jñāna (Scriptural Knowledge), Mati Jñāna (Sensory Knowledge), Avadhi Jñāna (Clairvoyance), and Manah prayāya Jñāna (Telepathy). According to the Jain text Tattvartha sūtra, the first two are indirect knowledge and the remaining three are direct knowledge.

Salvation, liberation

According to Jainism, purification of soul and liberation can be achieved through the path of four jewels: Samyak darśana (Correct View), meaning faith, acceptance of the truth of soul (jīva); Samyak gyana (Correct Knowledge), meaning undoubting knowledge of the tattvas; and Samyak charitra (Correct Conduct), meaning behavior consistent with the Five vows. Jain texts often add samyak tap (Correct Asceticism) as a fourth jewel, emphasizing belief in ascetic practices as the means to liberation (moksha). The four jewels are called moksha marg (the path of liberation).

Main principles

Non-violence (ahimsa)

The principle of ahimsa (non-violence or non-injury) is a fundamental tenet of Jainism. It holds that one must abandon all violent activity and that without such a commitment to non-violence all religious behavior is worthless. In Jain theology, it does not matter how correct or defensible the violence may be, one must not kill or harm any being, and non-violence is the highest religious duty. Jain texts such as Acaranga Sūtra and Tattvarthasūtra state that one must renounce all killing of living beings, whether tiny or large, movable or immovable. Its theology teaches that one must neither kill another living being, nor cause another to kill, nor consent to any killing directly or indirectly. Furthermore, Jainism emphasizes non-violence against all beings not only in action but also in speech and in thought. It states that instead of hate or violence against anyone, "all living creatures must help each other". Jains believe that violence negatively affects and destroys one's soul, particularly when the violence is done with intent, hate or carelessness, or when one indirectly causes or consents to the killing of a human or non-human living being.

The doctrine exists in Hinduism and Buddhism, but is most highly developed in Jainism. The theological basis of non-violence as the highest religious duty has been interpreted by some Jain scholars not to "be driven by merit from giving or compassion to other creatures, nor a duty to rescue all creatures", but resulting from "continual self-discipline", a cleansing of the soul that leads to one's own spiritual development which ultimately affects one's salvation and release from rebirths. Jains believe that causing injury to any being in any form creates bad karma which affects one's rebirth, future well being and causes suffering.

Late medieval Jain scholars re-examined the Ahiṃsā doctrine when faced with external threat or violence. For example, they justified violence by monks to protect nuns. According to Dundas, the Jain scholar Jinadattasuri wrote during a time of Muslim destruction of temples and persecution that "anybody engaged in a religious activity who was forced to fight and kill somebody would not lose any spiritual merit but instead attain deliverance". However, examples in Jain texts that condone fighting and killing under certain circumstances are relatively rare.

Many-sided reality (anekāntavāda)

The second main principle of Jainism is anekāntavāda, from anekānta ("many-sidedness") and vada ("doctrine"). The doctrine states that truth and reality are complex and always have multiple aspects. It further states that reality can be experienced, but cannot be fully expressed with language. It suggests that human attempts to communicate are Naya, "partial expression of the truth". According to it, one can experience the taste of truth, but cannot fully express that taste through language. It holds that attempts to express experience are syāt, or valid "in some respect", but remain "perhaps, just one perspective, incomplete". It concludes that in the same way, spiritual truths can be experienced but not fully expressed. It suggests that the great error is belief in ekānta (one-sidedness), where some relative truth is treated as absolute. The doctrine is ancient, found in Buddhist texts such as the Samaññaphala Sutta. The Jain Agamas suggest that Mahāvīra's approach to answering all metaphysical philosophical questions was a "qualified yes" (syāt). These texts identify anekāntavāda as a key difference from the Buddha's teachings. The Buddha taught the Middle Way, rejecting extremes of the answer "it is" or "it is not" to metaphysical questions. The Mahāvīra, in contrast, taught his followers to accept both "it is", and "it is not", qualified with "perhaps", to understand Absolute Reality. The permanent being is conceptualized as jiva (soul) and ajiva (matter) within a dualistic anekāntavāda framework.

According to Paul Dundas, in contemporary times the anekāntavāda doctrine has been interpreted by some Jains as intending to "promote a universal religious tolerance", and a teaching of "plurality" and "benign attitude to other [ethical, religious] positions". Dundas states this is a misreading of historical texts and Mahāvīra's teachings. According to him, the "many pointedness, multiple perspective" teachings of the Mahāvīra is about the nature of absolute reality and human existence. He claims that it is not about condoning activities such as killing animals for food, nor violence against disbelievers or any other living being as "perhaps right". The five vows for Jain monks and nuns, for example, are strict requirements and there is no "perhaps" about them. Similarly, since ancient times, Jainism co-existed with Buddhism and Hinduism according to Dundas, but Jainism disagreed, in specific areas, with the knowledge systems and beliefs of these traditions, and vice versa.

Non-attachment (aparigraha)

The third main principle in Jainism is aparigraha which means non-attachment to worldly possessions. For monks and nuns, Jainism requires a vow of complete non-possession of any property, relations and emotions. The ascetic is a wandering mendicant in the Digambara tradition, or a resident mendicant in the Śvētāmbara tradition. For Jain laypersons, it recommends limited possession of property that has been honestly earned, and giving excess property to charity. According to Natubhai Shah, aparigraha applies to both the material and the psychic. Material possessions refer to various forms of property. Psychic possessions refer to emotions, likes and dislikes, and attachments of any form. Unchecked attachment to possessions is said to result in direct harm to one's personality.

Jain ethics and five vows

Jainism teaches five ethical duties, which it calls five vows. These are called anuvratas (small vows) for Jain laypersons, and mahavratas (great vows) for Jain mendicants. For both, its moral precepts preface that the Jain has access to a guru (teacher, counsellor), deva (Jina, god), doctrine, and that the individual is free from five offences: doubts about the faith, indecisiveness about the truths of Jainism, sincere desire for Jain teachings, recognition of fellow Jains, and admiration for their spiritual pursuits. Such a person undertakes the following Five vows of Jainism:

- Ahiṃsā, "intentional non-violence" or "noninjury": The first major vow taken by Jains is to cause no harm to other human beings, as well as all living beings (particularly animals). This is the highest ethical duty in Jainism, and it applies not only to one's actions, but demands that one be non-violent in one's speech and thoughts.

- Satya, "truth": This vow is to always speak the truth. Neither lie, nor speak what is not true, and do not encourage others or approve anyone who speaks an untruth.

- Asteya, "not stealing": A Jain layperson should not take anything that is not willingly given. Additionally, a Jain mendicant should ask for permission to take it if something is being given.

- Brahmacharya, "celibacy": Abstinence from sex and sensual pleasures is prescribed for Jain monks and nuns. For laypersons, the vow means chastity, faithfulness to one's partner.

- Aparigraha, "non-possessiveness": This includes non-attachment to material and psychological possessions, avoiding craving and greed. Jain monks and nuns completely renounce property and social relations, own nothing and are attached to no one.

Jainism prescribes seven supplementary vows, including three guņa vratas (merit vows) and four śikşā vratas. The Sallekhana (or Santhara) vow is a "religious death" ritual observed at the end of life, historically by Jain monks and nuns, but rare in the modern age. In this vow, there is voluntary and gradual reduction of food and liquid intake to end one's life by choice and with dispassion. This is believed to reduce negative karma that affects a soul's future rebirths.

Practices

Asceticism and monasticism

Of the major Indian religions, Jainism has had the strongest ascetic tradition. Ascetic life may include nakedness, symbolizing non-possession even of clothes, fasting, body mortification, and penance, to burn away past karma and stop producing new karma, both of which are believed essential for reaching siddha and moksha ("liberation from rebirths" and "salvation").

Jain texts like Tattvartha Sūtra and Uttaradhyayana Sūtra discuss austerities in detail. Six outer and six inner practices are oft-repeated in later Jain texts. Outer austerities include complete fasting, eating limited amounts, eating restricted items, abstaining from tasty foods, mortifying the flesh, and guarding the flesh (avoiding anything that is a source of temptation). Inner austerities include expiation, confession, respecting and assisting mendicants, studying, meditation, and ignoring bodily wants in order to abandon the body. Lists of internal and external austerities vary with the text and tradition. Asceticism is viewed as a means to control desires, and to purify the jiva (soul). The tirthankaras such as the Mahāvīra (Vardhamana) set an example by performing severe austerities for twelve years.

Monastic organization, sangh, has a four-fold order consisting of sadhu (male ascetics, muni), sadhvi (female ascetics, aryika), śrāvaka (laymen), and śrāvikā (laywomen). The latter two support the ascetics and their monastic organizations called gacch or samuday, in autonomous regional Jain congregations. Jain monastic rules have encouraged the use of mouth cover, as well as the Dandasan – a long stick with woolen threads – to gently remove ants and insects that may come in their path.

Food and fasting

The practice of non-violence towards all living beings has led to Jain culture being vegetarian. Devout Jains practice lacto-vegetarianism, meaning that they eat no eggs, but accept dairy products if there is no violence against animals during their production. Veganism is encouraged if there are concerns about animal welfare. Jain monks, nuns and some followers avoid root vegetables such as potatoes, onions, and garlic because tiny organisms are injured when the plant is pulled up, and because a bulb or tuber's ability to sprout is seen as characteristic of a higher living being. Jain monks and advanced laypeople avoid eating after sunset, observing a vow of ratri-bhojana-tyaga-vrata. Monks observe a stricter vow by eating only once a day.

Jains fast particularly during festivals. This practice is called upavasa, tapasya or vrata, and may be practiced according to one's ability. Digambaras fast for Dasa-laksana-parvan, eating only one or two meals per day, drinking only boiled water for ten days, or fasting completely on the first and last days of the festival, mimicking the practices of a Jain mendicant for the period. Śvētāmbara Jains do similarly in the eight day paryusana with samvatsari-pratikramana. The practice is believed to remove karma from one's soul and provides merit (punya). A "one day" fast lasts about 36 hours, starting at sunset before the day of the fast and ending 48 minutes after sunrise the day after. Among laypeople, fasting is more commonly observed by women, as it shows her piety and religious purity, gains merit earning and helps ensure future well-being for her family. Some religious fasts are observed in a social and supportive female group. Long fasts are celebrated by friends and families with special ceremonies.

Meditation

Jainism considers meditation (dhyana) a necessary practice, but its goals are very different from those in Buddhism and Hinduism. In Jainism, meditation is concerned more with stopping karmic attachments and activity, not as a means to transformational insights or self-realization in other Indian religions. According to Padmanabh Jaini, Sāmāyika is a practice of "brief periods in meditation" in Jainism that is a part of siksavrata (ritual restraint). The goal of Sāmāyika is to achieve equanimity, and it is the second siksavrata. The samayika ritual is practiced at least three times a day by mendicants, while a layperson includes it with other ritual practices such as Puja in a Jain temple and doing charity work. According to Johnson, as well as Jaini, samayika connotes more than meditation, and for a Jain householder is the voluntary ritual practice of "assuming temporary ascetic status".

Rituals and worship

There are many rituals in Jainism's various sects. According to Dundas, the ritualistic lay path among Śvētāmbara Jains is "heavily imbued with ascetic values", where the rituals either revere or celebrate the ascetic life of Tirthankaras, or progressively approach the psychological and physical life of an ascetic. The ultimate ritual is sallekhana, a religious death through ascetic abandonment of food and drinks. The Digambara Jains follow the same theme, but the life cycle and religious rituals are closer to a Hindu liturgy. The overlap is mainly in the life cycle (rites-of-passage) rituals, and likely developed because Jain and Hindu societies overlapped, and rituals were viewed as necessary and secular.

Jains ritually worship numerous deities, especially the Jinas. In Jainism a Jina as deva is not an avatar (incarnation), but the highest state of omniscience that an ascetic tirthankara achieved. Out of the 24 Tirthankaras, Jains predominantly worship four: Mahāvīra, Parshvanatha, Neminatha and Rishabhanatha. Among the non-tirthankara saints, devotional worship is common for Bahubali among the Digambaras. The Panch Kalyanaka rituals remember the five life events of the tirthankaras, including the Panch Kalyanaka Pratishtha Mahotsava, Panch Kalyanaka Puja and Snatrapuja.

The basic ritual is darsana (seeing) of deva, which includes Jina, or other yaksas, gods and goddesses such as Brahmadeva, 52 Viras, Padmavati, Ambika and 16 Vidyadevis (including Sarasvati and Lakshmi). Terapanthi Digambaras limit their ritual worship to Tirthankaras. The worship ritual is called devapuja, and is found in all Jain sub-traditions. Typically, the Jain layperson enters the Derasar (Jain temple) inner sanctum in simple clothing and bare feet with a plate filled with offerings, bows down, says the namaskar, completes his or her litany and prayers, sometimes is assisted by the temple priest, leaves the offerings and then departs.

Jain practices include performing abhisheka (ceremonial bath) of the images. Some Jain sects employ a pujari (also called upadhye), who may be a Hindu, to perform priestly duties at the temple. More elaborate worship includes offerings such as rice, fresh and dry fruits, flowers, coconut, sweets, and money. Some may light up a lamp with camphor and make auspicious marks with sandalwood paste. Devotees also recite Jain texts, particularly the life stories of the tirthankaras.

Traditional Jains, like Buddhists and Hindus, believe in the efficacy of mantras and that certain sounds and words are inherently auspicious, powerful and spiritual. The most famous of the mantras, broadly accepted in various sects of Jainism, is the "five homage" (panca namaskara) mantra which is believed to be eternal and existent since the first tirthankara's time. Medieval worship practices included making tantric diagrams of the Rishi-mandala including the tirthankaras. The Jain tantric traditions use mantra and rituals that are believed to accrue merit for rebirth realms.

Festivals

The most important annual Jain festival is called the Paryushana by Svetambaras and Dasa lakshana parva by the Digambaras. It is celebrated from the 12th day of the waning moon in the traditional lunisolar month of Bhadrapada in the Indian calendar. This typically falls in August or September of the Gregorian calendar. It lasts eight days for Svetambaras, and ten days among the Digambaras. It is a time when lay people fast and pray. The five vows are emphasized during this time. Svetambaras recite the Kalpasūtras, while Digambaras read their own texts. The festival is an occasion where Jains make active effort to stop cruelty towards other life forms, freeing animals in captivity and preventing the slaughter of animals.

I forgive all living beings,

may all living beings forgive me.

All in this world are my friends,

I have no enemies.

— Jain festival prayer on the last day

The last day involves a focused prayer and meditation session known as Samvatsari. Jains consider this a day of atonement, granting forgiveness to others, seeking forgiveness from all living beings, physically or mentally asking for forgiveness and resolving to treat everyone in the world as friends. Forgiveness is asked by saying "Micchami Dukkadam" or "Khamat khamna" to others. This means, "If I have offended you in any way, knowingly or unknowingly, in thought, word or action, then I seek your forgiveness." The literal meaning of Paryushana is "abiding" or "coming together".

Mahavir Janma Kalyanak celebrates the birth of Mahāvīra. It is celebrated on the 13th day of the lunisolar month of Chaitra in the traditional Indian calendar. This typically falls in March or April of the Gregorian calendar. The festivities include visiting Jain temples, pilgrimages to shrines, reading Jain texts and processions of Mahāvīra by the community. At his legendary birthplace of Kundagrama in Bihar, north of Patna, special events are held by Jains. The next day of Dipawali is observed by Jains as the anniversary of Mahāvīra's attainment of moksha. The Hindu festival of Diwali is also celebrated on the same date (Kartika Amavasya). Jain temples, homes, offices, and shops are decorated with lights and diyas (small oil lamps). The lights are symbolic of knowledge or removal of ignorance. Sweets are often distributed. On Diwali morning, Nirvan Ladoo is offered after praying to Mahāvīra in all Jain temples across the world. The Jain new year starts right after Diwali. Some other festivals celebrated by Jains are Akshaya Tritiya and Raksha Bandhan, similar to those in the Hindu communities.

Traditions and sects

The Jain community is divided into two major denominations, Digambara and Śvētāmbara. Monks of the Digambara (sky-clad) tradition do not wear clothes. Female monastics of the Digambara sect wear unstitched plain white sarees and are referred to as Aryikas. Śvētāmbara (white-clad) monastics, on the other hand, wear seamless white clothes.

During Chandragupta Maurya's reign, Jain tradition states that Acharya Bhadrabahu predicted a twelve-year-long famine and moved to Karnataka with his disciples. Sthulabhadra, a pupil of Acharya Bhadrabahu, is believed to have stayed in Magadha. Later, as stated in tradition, when followers of Acharya Bhadrabahu returned, they found those who had remained at Magadha had started wearing white clothes, which was unacceptable to the others who remained naked. This is how Jains believe the Digambara and Śvētāmbara schism began, with the former being naked while the latter wore white clothes. Digambara saw this as being opposed to the Jain tenet of aparigraha which, according to them, required not even possession of clothes, i.e. complete nudity. In the 5th-century CE, the Council of Valabhi was organized by Śvētāmbara, which Digambara did not attend. At the council, the Śvētāmbara adopted the texts they had preserved as canonical scriptures, which Digambara has ever since rejected. This council is believed to have solidified the historic schism between these two major traditions of Jainism. The earliest record of Digambara beliefs is contained in the Prakrit Suttapahuda of Kundakunda.

Digambaras and Śvētāmbara differ in their practices and dress code, interpretations of teachings, and on Jain history especially concerning the tirthankaras. Their monasticism rules differ, as does their iconography. Śvētāmbara has had more female than male mendicants, where Digambara has mostly had male monks and considers males closest to the soul's liberation. The Śvētāmbaras believe that women can also achieve liberation through asceticism and state that the 19th Tirthankara Māllīnātha was female, which Digambara rejects.

Excavations at Mathura revealed Jain statues from the time of the Kushan Empire (c. 1st century CE). Tirthankara represented without clothes, and monks with cloth wrapped around the left arm, are identified as the Ardhaphalaka (half-clothed) mentioned in texts. The Yapaniyas, believed to have originated from the Ardhaphalaka, followed Digambara nudity along with several Śvētāmbara beliefs. In the modern era, according to Flügel, new Jain religious movements that are a "primarily devotional form of Jainism" have developed which resemble "Jain Mahayana" style devotionalism.

Scriptures and texts

Jain canonical scriptures are called Agamas. They are believed to have been verbally transmitted, much like the ancient Buddhist and Hindu texts, and to have originated from the sermons of the tirthankaras, whereupon the Ganadharas (chief disciples) transmitted them as Śhrut Jnāna (heard knowledge). The spoken scriptural language is believed to be Ardhamagadhi by the Śvētāmbara Jains, and a form of sonic resonance by the Digambara Jains.

The Śvētāmbaras believe that they have preserved 45 of the 50 original Jain scriptures (having lost an Anga text and four Purva texts), while the Digambaras believe that all were lost, and that Āchārya Bhutabali was the last ascetic who had partial knowledge of the original canon. According to them, Digambara Āchāryas recreated the oldest-known Digambara Jain texts, including the four anuyoga. The Digambara texts partially agree with older Śvētāmbara texts, but there are also gross differences between the texts of the two major Jain traditions. The Digambaras created a secondary canon between 600 and 900 CE, compiling it into four groups or Vedas: history, cosmography, philosophy and ethics.

The most popular and influential texts of Jainism have been its non-canonical literature. Of these, the Kalpa Sūtras are particularly popular among Śvētāmbaras, which they attribute to Bhadrabahu (c. 300 BCE). This ancient scholar is revered in the Digambara tradition, and they believe he led their migration into the ancient south Karnataka region and created their tradition. Śvētāmbaras believe instead that Bhadrabahu moved to Nepal. Both traditions consider his Niryuktis and Samhitas important. The earliest surviving Sanskrit text by Umaswati, the Tattvarthasūtra is considered authoritative by all traditions of Jainism. In the Digambara tradition, the texts written by Kundakunda are highly revered and have been historically influential. Other important Jain texts include: Samayasara, Ratnakaranda śrāvakācāra, and Niyamasara.

Comparison with Buddhism and Hinduism

All the three dharmic religions, viz., Jainism, Hinduism, and Buddhism, share concepts and doctrines such as karma and rebirth, with similar festivals and monastic traditions. They do not believe in eternal heaven or hell or judgment day. They grant the freedom to choose beliefs such as in gods or no-gods, to disagree with core teachings, and to choose whether to participate in prayers, rituals and festivals. They all consider values such as non-violence to be important, link suffering to craving, individual's actions, intents, and karma, and believe spirituality is a means to enlightened peace, bliss and eternal liberation (moksha).

Jainism differs from both Buddhism and Hinduism in its ontological premises. All believe in impermanence, but Buddhism incorporates the premise of anatta ("no eternal self or soul"). Hinduism incorporates an eternal unchanging atman ("soul"), while Jainism incorporates an eternal but changing jiva ("soul"). In Jain thought, there are infinite eternal jivas, predominantly in cycles of rebirth, and a few siddhas (perfected ones). Unlike Jainism, Hindu philosophies encompass nondualism where all souls are identical as Brahman and posited as interconnected one

While both Hinduism and Jainism believe "soul exists" to be a self-evident truth, most Hindu systems consider it to be eternally present, infinite and constant (vibhu), but some Hindu scholars propose soul to be atomic. Hindu thought generally discusses Atman and Brahman through a monistic or dualistic framework. In contrast, Jain thought denies the Hindu metaphysical concept of Brahman, and Jain philosophy considers the soul to be ever changing and bound to the body or matter for each lifetime, thereby having a finite size that infuses the entire body of a living being.

Jainism is similar to Buddhism in not recognizing the primacy of the Vedas and the Hindu Brahman. Jainism and Hinduism, however, both believe "soul exists" as a self-evident truth. Jains and Hindus have frequently intermarried, particularly in northern, central and western regions of India. Some early colonial scholars stated that Jainism like Buddhism was, in part, a rejection of the Hindu caste system, but later scholars consider this a Western error. A caste system not based on birth has been a historic part of Jain society, and Jainism focused on transforming the individual, not society.

Monasticism is similar in all three traditions, with similar rules, hierarchical structure, not traveling during the four-month monsoon season, and celibacy, originating before the Buddha or the Mahāvīra. Jain and Hindu monastic communities have traditionally been more mobile and had an itinerant lifestyle, while Buddhist monks have favored belonging to a sangha (monastery) and staying in its premises. Buddhist monastic rules forbid a monk to go outside without wearing the sangha's distinctive ruddy robe, or to use wooden bowls. In contrast, Jain monastic rules have either required nakedness (Digambara) or white clothes (Śvētāmbara), and they have disagreed on the legitimacy of the wooden or empty gourd as the begging bowl by Jain monks.

Jains have similar views with Hindus that violence in self-defence can be justified, and that a soldier who kills enemies in combat is performing a legitimate duty. Jain communities accepted the use of military power for their defence; there were Jain monarchs, military commanders, and soldiers. The Jain and Hindu communities have often been very close and mutually accepting. Some Hindu temples have included a Jain Tirthankara within its premises in a place of honour, while temple complexes such as the Badami cave temples and Khajuraho feature both Hindu and Jain monuments.

Art and architecture

Jainism has contributed significantly to Indian art and architecture. Jain arts depict life legends of tirthankara or other important people, particularly with them in a seated or standing meditative posture. Yakshas and yakshinis, attendant spirits who guard the tirthankara, are usually shown with them. The earliest known Jain image is in the Patna museum. It is dated approximately to the 3rd century BCE. Bronze images of Pārśva can be seen in the Prince of Wales Museum, Mumbai, and in the Patna museum; these are dated to the 2nd century BCE.

Ayagapata is a type of votive tablet used in Jainism for donation and worship in the early centuries. These tablets are decorated with objects and designs central to Jain worship such as the stupa, dharmacakra and triratna. They present simultaneous trends or image and symbol worship. Numerous such stone tablets were discovered during excavations at ancient Jain sites like Kankali Tila near Mathura in Uttar Pradesh, India. The practice of donating these tablets is documented from 1st century BCE to 3rd century CE. Samavasarana, a preaching hall of tirthankaras with various beings concentrically placed, is an important theme of Jain art.

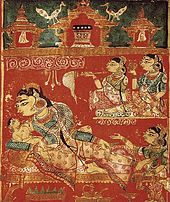

The Jain tower in Chittor, Rajasthan, is a good example of Jain architecture. Decorated manuscripts are preserved in Jain libraries, containing diagrams from Jain cosmology. Most of the paintings and illustrations depict historical events, known as Panch Kalyanaka, from the life of the tirthankara. Rishabha, the first tirthankara, is usually depicted in either the lotus position or kayotsarga, the standing position. He is distinguished from other tirthankara by the long locks of hair falling to his shoulders. Bull images also appear in his sculptures. In paintings, incidents from his life, like his marriage and Indra marking his forehead, are depicted. Other paintings show him presenting a pottery bowl to his followers; he is also seen painting a house, weaving, and being visited by his mother Marudevi. Each of the twenty-four tirthankara is associated with distinctive emblems, which are listed in such texts as Tiloyapannati, Kahavaali and Pravacanasaarodhara.

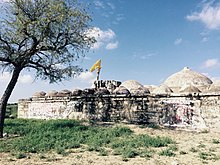

Temples

A Jain temple, a Derasar or Basadi, is a place of worship. Temples contain tirthankara images, some fixed, others moveable. These are stationed in the inner sanctum, one of the two sacred zones, the other being the main hall. One of the images is marked as the moolnayak (primary deity). A manastambha (column of honor) is a pillar that is often constructed in front of Jain temples. Temple construction is considered a meritorious act.

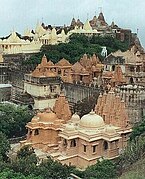

Ancient Jain monuments include the Udaigiri Hills near Bhelsa (Vidisha) in Madhya Pradesh, the Ellora in Maharashtra, the Palitana temples in Gujarat, and the Jain temples at Dilwara Temples near Mount Abu, Rajasthan. Chaumukha temple in Ranakpur is considered one of the most beautiful Jain temples and is famous for its detailed carvings. According to Jain texts, Shikharji is the place where twenty of the twenty-four Jain Tīrthaṅkaras along with many other monks attained moksha (died without being reborn, with their soul in Siddhashila). The Shikharji site in northeastern Jharkhand is therefore a revered pilgrimage site. The Palitana temples are the holiest shrine for the Śvētāmbara Murtipujaka sect. Along with Shikharji the two sites are considered the holiest of all pilgrimage sites by the Jain community. The Jain complex, Khajuraho and Jain Narayana temple are part of a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Shravanabelagola, Saavira Kambada Basadi or 1000 pillars and Brahma Jinalaya are important Jain centers in Karnataka. In and around Madurai, there are 26 caves, 200 stone beds, 60 inscriptions, and over 100 sculptures.

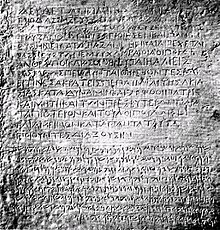

The 2nd–1st century BCE Udayagiri and Khandagiri Caves are rich with carvings of tirthanakars and deities with inscriptions including the Elephant Cave inscription. Jain cave temples at Badami, Mangi-Tungi and the Ellora Caves are considered important. The Sittanavasal Cave temple is a fine example of Jain art with an early cave shelter, and a medieval rock-cut temple with excellent fresco paintings comparable to Ajantha. Inside are seventeen stone beds with 2nd century BCE Tamil-Brahmi inscriptions. The 8th century Kazhugumalai temple marks the revival of Jainism in South India.

- Jain temples of varied styles in India and abroad

Pilgrimages

Jain Tirtha (pilgrim) sites are divided into the following categories:

- Siddhakshetra – Site believed to be of the moksha of an arihant (kevalin) or tirthankara, such as: Ashtapada, Shikharji, Girnar, Pawapuri, Palitana, Mangi-Tungi, and Champapuri (capital of Anga).

- Atishayakshetra – Locations where divine events are believed to have occurred, such as: Mahavirji, Rishabhdeo, Kundalpur, Tijara, and Aharji.

- Puranakshetra – Places associated with the lives of great men, such as: Ayodhya, Vidisha, Hastinapur, and Rajgir.

- Gyanakshetra – Places associated with famous acharyas, or centers of learning, such as Shravanabelagola.

Outside contemporary India, Jain communities built temples in locations such as Nagarparkar, Sindh (Pakistan). However, according to a UNESCO tentative world heritage site application, Nagarparkar was not a "major religious centre or a place of pilgrimage" for Jainism, but it was once an important cultural landscape before "the last remaining Jain community left the area in 1947 at Partition".

Statues and sculptures

Jain sculptures usually depict one of the twenty-four tīrthaṅkaras; Parshvanatha, Rishabhanatha and Mahāvīra are among the more popular, often seated in lotus position or kayotsarga, along with Arihant, Bahubali, and protector deities like Ambika. Quadruple images are also popular. Tirthankar idols look similar, differentiated by their individual symbol, except for Parshvanatha whose head is crowned by a snake. Digambara images are naked without any beautification, whereas Śvētāmbara depictions are clothed and ornamented.

A monolithic, 18-metre (59-foot) statue of Bahubali, Gommateshvara, built in 981 CE by the Ganga minister and commander Chavundaraya, is situated on a hilltop in Shravanabelagola in Karnataka. This statue was voted first in the SMS poll Seven Wonders of India conducted by The Times of India. The 33 m (108 ft) tall Statue of Ahiṃsā (depicting Rishabhanatha) was erected in the Nashik district in 2015. Idols are often made in Ashtadhatu (literally "eight metals"), namely Akota Bronze, brass, gold, silver, stone monoliths, rock cut, and precious stones.

Symbols

Jain icons and arts incorporate symbols such as the swastika, Om, and the Ashtamangala. In Jainism, Om is a condensed reference to the initials "A-A-A-U-M" of the five parameshthis: "Arihant, Ashiri, Acharya, Upajjhaya, Muni", or the five lines of the Ṇamōkāra Mantra. The Ashtamangala is a set of eight auspicious symbols: in the Digambara tradition, these are Chatra, Dhvaja, Kalasha, Fly-whisk, Mirror, Chair, Hand fan and Vessel. In the Śvētāmbar tradition, they are Swastika, Srivatsa, Nandavarta, Vardhmanaka (food vessel), Bhadrasana (seat), Kalasha (pot), Darpan (mirror) and pair of fish.

The hand with a wheel on the palm symbolizes ahimsā. The wheel represents the dharmachakra, which stands for the resolve to halt the saṃsāra (wandering) through the relentless pursuit of ahimsā. The five colours of the Jain flag represent the Pañca-Parameṣṭhi and the five vows. The swastika's four arms symbolise the four realms in which rebirth occurs according to Jainism: humans, heavenly beings, hellish beings and non-humans. The three dots on the top represent the three jewels mentioned in ancient texts: correct faith, correct understanding and correct conduct, believed to lead to spiritual perfection.

In 1974, on the 2500th anniversary of the nirvana of Mahāvīra, the Jain community chose a single combined image for Jainism. It depicts the three lokas, heaven, the human world and hell. The semi-circular topmost portion symbolizes Siddhashila, a zone beyond the three realms. The Jain swastika and the symbol of Ahiṃsā are included, with the Jain mantra Parasparopagraho Jīvānām from sūtra 5.21 of Umaswati's Tattvarthasūtra, meaning "souls render service to one another".

History

Ancient

Jainism is an ancient Indian religion of obscure origins. Jains claim it to be eternal, and consider the first tirthankara Rishabhanatha as the reinforcer of Jain Dharma in the current time cycle. Scholars have conjectured that images such as those of the bull in Indus Valley Civilization seal are related to Jainism. It is one of the Śramaṇa traditions of ancient India, those that rejected the Vedas, and according to the philosopher Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, it existed before them.

The historicity of first twenty two Tirthankars is not traced yet. The 23rd tirthankar, Parshvanatha, was a historical being, of the ninth century BCE. Mahāvīra is considered a contemporary of the Buddha, in around the 6th century BCE. The interaction between the two religions began with the Buddha; later, they competed for followers and the merchant trade networks that sustained them. Buddhist and Jain texts sometimes have the same or similar titles but present different doctrines.

Jains consider the kings Bimbisara (c. 558–491 BCE), Ajatashatru (c. 492–460 BCE), and Udayin (c. 460–440 BCE) of the Haryanka dynasty as patrons of Jainism. Jain tradition states that Chandragupta Maurya (322–298 BCE), the founder of the Mauryan Empire and grandfather of Ashoka, became a monk and disciple of Jain ascetic Bhadrabahu in the later part of his life. Jain texts state that he died intentionally at Shravanabelagola by fasting. Versions of Chandragupta's story appear in Buddhist, Jain, and Hindu texts.

The 3rd century BCE emperor Ashoka, in his pillar edicts, mentions the Niganthas (Jains). Tirthankara statues date back to the second century BCE. Archeological evidence suggests that Mathura was an important Jain center from the 2nd century BCE onwards. Inscriptions from as early as the 1st century CE already show the schism between Digambara and Śvētāmbara. There is inscriptional evidence for the presence of Jain monks in south India by the second or first centuries BCE, and archaeological evidence of Jain monks in Saurashtra in Gujarat by the second century CE.

Royal patronage has been a key factor in the growth and decline of Jainism. In the second half of the 1st century CE, Hindu kings of the Rashtrakuta dynasty sponsored major Jain cave temples. King Harshavardhana of the 7th century championed Jainism, Buddhism and all traditions of Hinduism. The Pallava King Mahendravarman I (600–630 CE) converted from Jainism to Shaivism. His work Mattavilasa Prahasana ridicules certain Shaiva sects and the Buddhists and expresses contempt for Jain ascetics. The Yadava dynasty built many temples at the Ellora Caves between 700 and 1000 CE. King Āma of the 8th century converted to Jainism, and the Jain pilgrimage tradition was well established in his era. Mularaja (10th century CE), the founder of the Chalukya dynasty, constructed a Jain temple, even though he was not a Jain. During the 11th century, Basava, a minister to the Jain Kalachuri king Bijjala, converted many Jains to the Lingayat Shaivite sect. The Lingayats destroyed Jain temples and adapted them to their use. The Hoysala King Vishnuvardhana (c. 1108–1152 CE) became a Vaishnavite under the influence of Ramanuja, and Vaishnavism then grew rapidly in what is now Karnataka.

Medieval

Jainism faced persecution during and after the Muslim conquests on the Indian subcontinent. Muslims rulers, such as Mahmud Ghazni (1001), Mohammad Ghori (1175) and Ala-ud-din Muhammed Shah Khalji (1298) further oppressed the Jain community. They vandalised idols and destroyed temples or converted them into mosques. They also burned Jain books and killed Jains. There were significant exceptions, such as Emperor Akbar (1542–1605) whose legendary religious tolerance, out of respect for Jains, ordered the release of caged birds and banned the killing of animals on the Jain festival of Paryusan. After Akbar, Jains faced an intense period of Muslim persecution in the 17th century. The Jain community were the traditional bankers and financiers, and this significantly impacted the Muslim rulers. However, they rarely were a part of the political power during the Islamic rule period of the Indian subcontinent.

Colonial era

A Gujarati Jain scholar Virchand Gandhi represented Jainism at the first World Parliament of Religions in 1893, held in America during the Chicago World’s Fair. He worked to defend the rights of Jains, and wrote and lectured extensively on Jainism.

Shrimad Rajchandra, a mystic, poet and philosopher spearheaded the revival of Jainism in Gujarat. He performed śatāvadhāna (100 Avadhāna) at Sir Framji Cowasji Institute in Bombay on 22 January 1887, which gained him praise and publicity. He was awarded gold medals by institutes and public for his performances as well as title of Sakshat Saraswati (Incarnation of the Goddess of Knowledge) while he was a teenager. The performances attracted wide coverage in national newspapers. Virchand Gandhi mentioned this feat at the Parliament of the World's Religions. He was well known as a spiritual guide of Mahatma Gandhi. They were introduced in Mumbai in 1891 and had various conversations through letters while Gandhi was in South Africa. Gandhi noted his impression of Shrimad Rajchandra in his autobiography, The Story of My Experiments with Truth, calling him his "guide and helper" and his "refuge in moments of spiritual crisis". His teaching directly influenced Gandhi's non-violence philosophy.

Colonial era reports and Christian missions variously viewed Jainism as a sect of Hinduism, a sect of Buddhism, or a distinct religion. Christian missionaries were frustrated at Jain people without pagan creator gods refusing to convert to Christianity, while colonial era Jain scholars such as Champat Rai Jain defended Jainism against criticism and misrepresentation by Christian activists. Missionaries of Christianity and Islam considered Jain traditions idolatrous and superstitious. These criticisms, states John E. Cort, were flawed and ignored similar practices within sects of Christianity.

The British colonial government in India and Indian princely states promoted religious tolerance. However, laws were passed that made roaming naked by anyone an arrestable crime. This drew popular support from the majority Hindu population, but particularly impacted Digambara monks. The Akhil Bharatiya Jain Samaj opposed this law, claiming that it interfered with Jain religious rights. Acharya Shantisagar entered Bombay (now Mumbai) in 1927, but was forced to cover his body. He then led an India-wide tour as the naked monk with his followers, to various Digambara sacred sites, and was welcomed by kings of the Maharashtra provinces. Shantisagar fasted to oppose the restrictions imposed on Digambara monks by the British Raj and prompted their discontinuance. The laws were abolished by India after independence.

Modern era

Followers of Jainism are called "Jains", a word derived from the Sanskrit jina (victor), which means an omniscient person who teaches the path of salvation. The majority of Jains currently reside in India. With four to five million followers worldwide, Jainism is small compared to major world religions. Jains form 0.37% of India's population, mostly in the states of Maharashtra (1.4 million in 2011, 31.46% of Indian Jains), Rajasthan (13.97%), Gujarat (13.02%) and Madhya Pradesh (12.74%). Significant Jain populations exist in Karnataka (9.89%), Uttar Pradesh (4.79%), Delhi (3.73%) and Tamil Nadu (2.01%). Outside India, Jain communities can be found in most areas hosting large Indian populations, such as Europe, the United Kingdom, the United States, Canada, Australia and Kenya. Jainism also counts several non-Indian converts; for example, it is spreading rapidly in Japan, where more than 5,000 families have converted between 2010-2020.

According to the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-4) conducted in 2015–16, Jains form the wealthiest community in India. According to its 2011 census, they have the country's highest literacy rate (87%) among those aged seven and older, and the most college graduates; excluding the retired, Jain literacy in India exceeded 97%. The female to male sex ratio among Jains is .940; among Indians in the 0–6 year age range the ratio was second lowest (870 girls per 1,000 boys), higher only than Sikhs. Jain males have the highest work participation rates in India, while Jain females have the lowest.

Jainism has been praised for some of its practices and beliefs. The leader of the campaign for Indian independence, Mahatma Gandhi, was greatly influenced by Jainism, stating:

No religion in the World has explained the principle of Ahiṃsā so deeply and systematically as is discussed with its applicability in every human life in Jainism. As and when the benevolent principle of Ahiṃsā or non-violence will be ascribed for practice by the people of the world to achieve their end of life in this world and beyond, Jainism is sure to have the uppermost status and Mahāvīra is sure to be respected as the greatest authority on Ahiṃsā.

Chandanaji became the first Jain woman to receive the title of Acharya in 1987.