| Taoism | |||

|---|---|---|---|

Tao, a Chinese word signifying "way", "path", "route", "road" or sometimes more loosely "doctrine". | |||

| Chinese | 道教 | ||

| Hanyu Pinyin | Dàojiào | ||

| Literal meaning | "Way Tradition" | ||

Taoism (/ˈtaʊ-/), or Daoism (/ˈdaʊɪzəm/), is a philosophical and spiritual tradition of Chinese origin which emphasizes living in harmony with the Tao (Chinese: 道; pinyin: Dào; lit. 'Way', or Dao). In Taoism the Tao is the source, pattern and substance of everything that exists. Taoism teaches about the various disciplines for achieving "perfection" by becoming one with the unplanned rhythms of the universe, called "the way" or "Tao". Taoist ethics vary depending on the particular school, but in general tend to emphasize wu wei (action without intention), "naturalness", simplicity, spontaneity and the Three Treasures: 慈, "compassion", 儉, "frugality" and 不敢為天下先, "humility".

The roots of Taoism go back at least to the 4th century BCE. Early Taoism drew its cosmological notions from the School of Yinyang (Naturalists) and was deeply influenced by one of the oldest texts of Chinese culture, the I Ching (Yi Jing), which expounds a philosophical system about how to keep human behaviour in accordance with the alternating cycles of nature. The "Legalist" Shen Buhai (c. 400 – c. 337 BCE) may also have been a major influence, expounding a realpolitik of wu wei. The Tao Te Ching (Dao De Jing), a compact book containing teachings attributed to Lao Tzu (老子; Lǎozǐ; Lao³ Tzŭ³), is widely considered the keystone work of the Taoist tradition, together with the later writings of Zhuangzi.

Taoism has had a profound influence on Chinese culture in the course of the centuries and Taoists (dàoshi, "masters of the Tao"), a title traditionally attributed only to the clergy and not to their lay followers, usually take care to note the distinction between their ritual tradition and the practices of Chinese folk religion and non-Taoist vernacular ritual orders, which are often mistakenly identified as pertaining to Taoism. Chinese alchemy (especially neidan), Chinese astrology, Chan (Zen) Buddhism, several martial arts, traditional Chinese medicine, feng shui and many styles of qigong have been intertwined with Taoism throughout history.

Today, the Taoist tradition is one of the five religious doctrines officially recognized by the People's Republic of China. It is also a major religion in Taiwan and claims adherents in a number of other societies, in particular in Hong Kong, Macau and Southeast Asia.

Definition

Spelling and pronunciation

Since the introduction of the Pinyin system for romanizing Mandarin Chinese, there have been those who have felt that "Taoism" would be more appropriately spelled as "Daoism". The Mandarin Chinese pronunciation for the word 道 ("way, path") is spelled as tao4 in the older Wade–Giles romanization system (from which the spelling 'Taoism' is derived), while it is spelled as dào in the newer Pinyin romanization system (from which the spelling "Daoism" is derived). Both the Wade–Giles tao4 and the Pinyin dào are intended to be pronounced identically in Mandarin Chinese (like the unaspirated 't' in 'stop'), but despite this fact, "Taoism" and "Daoism" can be pronounced differently in English vernacular.

Categorization

The word Taoism is used to translate different Chinese terms which refer to different aspects of the same tradition and semantic field:

- "Taoist religion" (道敎; Dàojiào; lit. "teachings of the Tao"), or the "liturgical" aspect – A family of organized religious movements sharing concepts or terminology from "Taoist philosophy"; the first of these is recognized as the Celestial Masters school.

- "Taoist philosophy" (道家; Dàojiā; lit. "school or family of the Tao") or "Taology" (道學; dàoxué; lit. "learning of the Tao"), or the "mystical" aspect – The philosophical doctrines based on the texts of the Yi Jing, the Tao Te Ching (or Dao De Jing, 道德經; dàodéjīng) and the Zhuangzi (莊子; zhuāngzi). These texts were linked together as "Taoist philosophy" during the early Han Dynasty, but notably not before. It is unlikely that Zhuangzi was familiar with the text of the Tao Te Ching, and Zhuangzi would not have identified himself as a Taoist as this classification did not arise until well after his death.

However, the discussed distinction is rejected by the majority of Western and Japanese scholars. It is contested by hermeneutic (interpretive) difficulties in the categorization of the different Taoist schools, sects and movements. Taoism does not fall under an umbrella or a definition of a single organized religion like the Abrahamic traditions; nor can it be studied as a mere variant of Chinese folk religion, as although the two share some similar concepts, much of Chinese folk religion is separate from the tenets and core teachings of Taoism. The sinologists Isabelle Robinet and Livia Kohn agree that "Taoism has never been a unified religion, and has constantly consisted of a combination of teachings based on a variety of original revelations."

The philosopher Chung-ying Cheng views Taoism as a religion that has been embedded into Chinese history and tradition. "Whether Confucianism, Taoism, or later Chinese Buddhism, they all fall into this pattern of thinking and organizing and in this sense remain religious, even though individually and intellectually they also assume forms of philosophy and practical wisdom." Chung-ying Cheng also noted that the Taoist view of heaven flows mainly from "observation and meditation, [though] the teaching of the way (Tao) can also include the way of heaven independently of human nature". In Chinese history, the three religions of Buddhism, Taoism and Confucianism stand on their own independent views, and yet are "involved in a process of attempting to find harmonization and convergence among themselves, so that we can speak of a 'unity of three religious teachings' (三敎合一; Sānjiào Héyī).

The term "Taoist" and "Taoism" as a "liturgical framework"

Traditionally, the Chinese language does not have terms defining lay people adhering to the doctrines or the practices of Taoism, who fall instead within the field of folk religion. "Taoist", in Western sinology, is traditionally used to translate Taoshih (道士, "master of the Tao"), thus strictly defining the priests of Taoism, ordained clergymen of a Taoist institution who "represent Taoist culture on a professional basis", are experts of Taoist liturgy, and therefore can employ this knowledge and ritual skills for the benefit of a community.

This role of Taoist priests reflects the definition of Taoism as a "liturgical framework for the development of local cults", in other words a scheme or structure for Chinese religion, proposed first by the scholar and Taoist initiate Kristofer Schipper in The Taoist Body (1986). Taoshih are comparable to the non-Taoist fashi (法師, "ritual masters") of vernacular traditions (the so-called "Faism") within Chinese religion.

The term dàojiàotú (道敎徒; 'follower of Taoism'), with the meaning of "Taoist" as "lay member or believer of Taoism", is a modern invention that goes back to the introduction of the Western category of "organized religion" in China in the 20th century, but it has no significance for most of Chinese society in which Taoism continues to be an "order" of the larger body of Chinese religion.

History

Lao Tzu is traditionally regarded as one of the founders of Taoism and is closely associated in this context with "original" or "primordial" Taoism. Whether he actually existed is disputed; however, the work attributed to him—the Tao Te Ching—is dated to the late 4th century BCE.

Taoism draws its cosmological foundations from the School of Naturalists (in the form of its main elements—yin and yang and the Five Phases), which developed during the Warring States period (4th to 3rd centuries BCE).

Robinet identifies four components in the emergence of Taoism:

- Philosophical Taoism, i.e. the Tao Te Ching and Zhuangzi

- techniques for achieving ecstasy

- practices for achieving longevity or immortality

- exorcism.

Some elements of Taoism may be traced to prehistoric folk religions in China that later coalesced into a Taoist tradition. In particular, many Taoist practices drew from the Warring-States-era phenomena of the wu (connected to the shamanic culture of northern China) and the fangshi (which probably derived from the "archivist-soothsayers of antiquity, one of whom supposedly was Lao Tzu himself"), even though later Taoists insisted that this was not the case. Both terms were used to designate individuals dedicated to "... magic, medicine, divination,... methods of longevity and to ecstatic wanderings" as well as exorcism; in the case of the wu, "shamans" or "sorcerers" is often used as a translation. The fangshi were philosophically close to the School of Naturalists, and relied much on astrological and calendrical speculations in their divinatory activities.

The first organized form of Taoism, the Way of the Celestial Masters's school (later known as Zhengyi school), developed from the Five Pecks of Rice movement at the end of the 2nd century CE; the latter had been founded by Zhang Taoling, who said that Lao Tzu appeared to him in the year 142. The Way of the Celestial Masters school was officially recognized by ruler Cao Cao in 215, legitimizing Cao Cao's rise to power in return. Lao Tzu received imperial recognition as a divinity in the mid-2nd century BCE.

By the Han dynasty (206 BCE–220 CE), the various sources of Taoism had coalesced into a coherent tradition of religious organizations and orders of ritualists in the state of Shu (modern Sichuan). In earlier ancient China, Taoists were thought of as hermits or recluses who did not participate in political life. Zhuangzi was the best known of these, and it is significant that he lived in the south, where he was part of local Chinese shamanic traditions.

Female shamans played an important role in this tradition, which was particularly strong in the southern state of Chu. Early Taoist movements developed their own institution in contrast to shamanism but absorbed basic shamanic elements. Shamans revealed basic texts of Taoism from early times down to at least the 20th century. Institutional orders of Taoism evolved in various strains that in more recent times are conventionally grouped into two main branches: Quanzhen Taoism and Zhengyi Taoism. After Lao Tzu and Zhuangzi, the literature of Taoism grew steadily and was compiled in form of a canon—the Tao Tsang—which was published at the behest of the emperor. Throughout Chinese history, Taoism was nominated several times as a state religion. After the 17th century, however, it fell from favor.

Taoism, in form of the Shangqing school, gained official status in China again during the Tang dynasty (618–907), whose emperors claimed Lao Tzu as their relative. The Shangqing movement, however, had developed much earlier, in the 4th century, on the basis of a series of revelations by gods and spirits to a certain Yang Xi in the years between 364 and 370.

Between 397 and 402, Ge Chaofu compiled a series of scriptures which later served as the foundation of the Lingbao school, which unfolded its greatest influence during the Song dynasty (960–1279). Several Song emperors, most notably Huizong, were active in promoting Taoism, collecting Taoist texts and publishing editions of the Taotsang.

In the 12th century, the Quanzhen School was founded in Shandong. It flourished during the 13th and 14th centuries and during the Yuan dynasty became the largest and most important Taoist school in Northern China. The school's most revered master, Qiu Chuji, met with Genghis Khan in 1222 and was successful in influencing the Khan towards exerting more restraint during his brutal conquests. By the Khan's decree, the school also was exempt from taxation.

Aspects of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism were consciously synthesized in the Neo-Confucian school, which eventually became Imperial orthodoxy for state bureaucratic purposes under the Ming (1368–1644).

During the Qing dynasty (1644–1912), however, due to discouragements of the government, many people favored Confucian and Buddhist classics over Taoist works.

During the 18th century, the imperial library was constituted, but excluded virtually all Taoist books. By the beginning of the 20th century, Taoism went through many catastrophic events. (As a result, only one complete copy of the Tao Tsang still remained, at the White Cloud Monastery in Beijing).

Today, Taoism is one of five official recognized religions in the People's Republic of China. The government regulates its activities through the Chinese Taoist Association. However, Taoism is practiced without government involvement in Taiwan, where it claims millions of adherents.

World Heritage Sites Mount Qingcheng and Mount Longhu are thought to be among the birthplaces of Taoism.

Doctrines

Ethics

Taoism tends to emphasize various themes of the Tao Te Ching and Zhuangzi, such as naturalness, spontaneity, simplicity, detachment from desires, and most important of all, wu wei. However, the concepts of those keystone texts cannot be equated with Taoism as a whole.

Tao and Te

Tao (道; dào) literally means "way", but can also be interpreted as road, channel, path, doctrine, or line. In Taoism, it is "the One, which is natural, spontaneous, eternal, nameless, and indescribable. It is at once the beginning of all things and the way in which all things pursue their course." It has variously been denoted as the "flow of the universe", a "conceptually necessary ontological ground", or a demonstration of nature. The Tao also is something that individuals can find immanent in themselves.

The active expression of Tao is called Te (also spelled—and pronounced—De, or even Teh; often translated with Virtue or Power; 德; dé), in a sense that Te results from an individual living and cultivating the Tao.

Wu-wei

The ambiguous term wu-wei (無爲; wú wéi) constitutes the leading ethical concept in Taoism. Wei refers to any intentional or deliberated action, while wu carries the meaning of "there is no ..." or "lacking, without". Common translations are "nonaction", "effortless action" or "action without intent". The meaning is sometimes emphasized by using the paradoxical expression "wei wu wei": "action without action".

In ancient Taoist texts, wu-wei is associated with water through its yielding nature. Taoist philosophy, in accordance with the I Ching, proposes that the universe works harmoniously according to its own ways. When someone exerts their will against the world in a manner that is out of rhythm with the cycles of change, they may disrupt that harmony and unintended consequences may more likely result rather than the willed outcome. Taoism does not identify one's will as the root problem. Rather, it asserts that one must place their will in harmony with the natural universe. Thus, a potentially harmful interference may be avoided, and in this way, goals can be achieved effortlessly. "By wu-wei, the sage seeks to come into harmony with the great Tao, which itself accomplishes by nonaction."

Ziran

Ziran (自然; zìrán; tzu-jan; lit. "self-such", "self-organization") is regarded as a central value in Taoism. It describes the "primordial state" of all things as well as a basic character of the Tao, and is usually associated with spontaneity and creativity. To attain naturalness, one has to identify with the Tao; this involves freeing oneself from selfishness and desire, and appreciating simplicity.

An often cited metaphor for naturalness is pu (樸; pǔ, pú; p'u; lit. "uncut wood"), the "uncarved block", which represents the "original nature... prior to the imprint of culture" of an individual. It is usually referred to as a state one returns to.

Three Treasures

The Taoist Three Treasures or Three Jewels (三寶; sānbǎo) comprise the basic virtues of ci (慈; cí, usually translated as compassion), jian (儉; jiǎn, usually translated as moderation), and bugan wei tianxia xian (不敢爲天下先; bùgǎn wéi tiānxià xiān, literally "not daring to act as first under the heavens", but usually translated as humility).

As the "practical, political side" of Taoist philosophy, Arthur Waley translated them as "abstention from aggressive war and capital punishment", "absolute simplicity of living", and "refusal to assert active authority".

The Three Treasures can also refer to jing, qi and shen (精氣神; jīng-qì-shén; jing is usually translated as essence, qi as life force, and shen as spirit). These terms are elements of the traditional Chinese concept of the human body, which shares its cosmological foundation—Yinyangism or the Naturalists—with Taoism. Within this framework, they play an important role in neidan ("Taoist Inner Alchemy").

Cosmology

Taoist cosmology is cyclic—the universe is seen as being in a constant process of re-creating itself. Evolution and 'extremes meet' are main characters. Taoist cosmology shares similar views with the School of Naturalists (Yinyang) which was headed by Zou Yan (305–240 BCE). The school's tenets harmonized the concepts of the Wu Xing (Five Elements) and yin and yang. In this spirit, the universe is seen as being in a constant process of re-creating itself, as everything that exists is a mere aspect of qi, which "condensed, becomes life; diluted, it is indefinite potential". Qi is in a perpetual transformation between its condensed and diluted state. These two different states of qi, on the other hand, are embodiments of the abstract entities of yin and yang, two complementary extremes that constantly play against and with each other and one cannot exist without the other.

Human beings are seen as a microcosm of the universe, and for example comprise the Wu Xing in form of the zang-fu organs. As a consequence, it is believed that deeper understanding of the universe can be achieved by understanding oneself.

Theology

Taoist theology can be defined as apophatic, given its philosophical emphasis on the formlessness and unknowable nature of the Tao, and the primacy of the "Way" rather than anthropomorphic concepts of God. This is one of the core beliefs that nearly all the sects share.

Taoist orders usually present the Three Pure Ones at the top of the pantheon of deities, visualizing the hierarchy emanating from the Tao. Lao Tzu is considered the incarnation of one of the Three Purities and worshiped as the ancestor of the philosophical doctrine.

Different branches of Taoism often have differing pantheons of lesser deities, where these deities reflect different notions of cosmology. Lesser deities also may be promoted or demoted for their activity. Some varieties of popular Chinese religion incorporate the Jade Emperor, derived from the main of the Three Purities, as a representation of the most high God.

Persons from the history of Taoism, and people who are considered to have become immortals (xian), are venerated as well by both clergy and laypeople.

Despite these hierarchies of deities, traditional conceptions of Tao should not be confused with the Western theism. Being one with the Tao does not necessarily indicate a union with an eternal spirit in, for example, the Hindu sense.

Texts

Tao Te Ching

The Tao Te Ching or Taodejing is widely considered the most influential Taoist text. According to legend, it was written by Lao Tzu, and often the book is simply referred to as the "Lao Tzu." However, authorship, precise date of origin, and even unity of the text are still subject of debate, and will probably never be known with certainty. The earliest texts of the Tao Te Ching that have been excavated (written on bamboo tablets) date back to the late 4th century BCE. Throughout the history of religious Taoism, the Tao Te Ching has been used as a ritual text.

The famous opening lines of the Tao Te Ching are:

道可道非常道 (pinyin: dào kĕ dào fēi cháng dào)

"The Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao"

名可名非常名 (pinyin: míng kĕ míng fēi cháng míng)

"The name that can be named is not the eternal name."

There is significant, at times acrimonious, debate regarding which English translation of the Tao Te Ching is preferable, and which particular translation methodology is best. The Tao Te Ching is not thematically ordered. However, the main themes of the text are repeatedly expressed using variant formulations, often with only a slight difference.

The leading themes revolve around the nature of Tao and how to attain it. Tao is said to be ineffable, and accomplishing great things through small means. Ancient commentaries on the Tao Te Ching are important texts in their own right. Perhaps the oldest one, the Heshang Gong commentary, was most likely written in the 2nd century CE. Other important commentaries include the one from Wang Bi and the Xiang'er.

Zhuangzi

The Zhuangzi (莊子), named after its traditional author Zhuangzi, is a composite of writings from various sources, and is generally considered the most important of all Taoist writings. The commentator Guo Xiang (c. CE 300) helped establish the text as an important source for Taoist thought. The traditional view is that Zhuangzi himself wrote the first seven chapters (the "inner chapters") and his students and related thinkers were responsible for the other parts (the "outer" and "miscellaneous" chapters). The work uses anecdotes, parables and dialogues to express one of its main themes, that is aligning oneself to the laws of the natural world and "the way" of the elements.

I Ching

The I Ching was originally a divination system that had its origins around 1150 BCE. Although it predates the first mentions of Tao as an organized system of philosophy and religious practice, this text later became of philosophical importance to Taoism and Confucianism.

The I Ching itself, shorn of its commentaries, consists of 64 combinations of 8 trigrams (called "hexagrams"), traditionally chosen by throwing coins or yarrow sticks, to give the diviner some idea of the situation at hand and, through reading of the "changing lines", some idea of what is developing.

The 64 original notations of the hexagrams in the I Ching can also be read as a meditation on how change occurs, so it assists Taoists with managing yin and yang cycles as Laozi advocated in the Tao Te Ching (the oldest known version of this text was dated to 400 BCE). More recently as recorded in the 18th century, the Taoist master Liu Yiming continued to advocate this usage.

The Taoist Canon

The Taoist Canon (道藏, Treasury of Tao) is also referred to as the Taotsang. It was originally compiled during the Jin, Tang, and Song dynasties. The extant version was published during the Ming Dynasty. The Ming Taotsang includes almost 1500 texts. Following the example of the Buddhist Tripiṭaka, it is divided into three dong (洞, "caves", "grottoes"). They are arranged from "highest" to "lowest":

- The Zhen ("real" or "truth" 眞) grotto. Includes the Shangqing texts.

- The Xuan ("mystery" 玄) grotto. Includes the Lingbao scriptures.

- The Shen ("divine" 神) grotto. Includes texts predating the Maoshan (茅山) revelations.

Taoist generally do not consult published versions of the Taotsang, but individually choose, or inherit, texts included in the Taotsang. These texts have been passed down for generations from teacher to student.

The Shangqing School has a tradition of approaching Taoism through scriptural study. It is believed that by reciting certain texts often enough one will be rewarded with immortality.

Other texts

While the Tao Te Ching is most famous, there are many other important texts in traditional Taoism. Taishang Ganying Pian ("Treatise of the Exalted One on Response and Retribution") discusses sin and ethics, and has become a popular morality tract in the last few centuries. It asserts that those in harmony with Tao will live long and fruitful lives. The wicked, and their descendants, will suffer and have shortened lives.

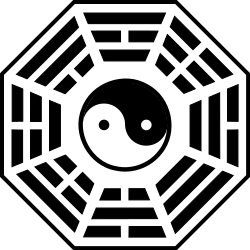

Symbols and images

The taijitu (太極圖; tàijítú; commonly known as the "yin and yang symbol" or simply the "yin yang") and the Ba-gua 八卦 ("Eight Trigrams") have importance in Taoist symbolism. In this cosmology, the universe creates itself out of a primary chaos of material energy, organized into the cycles of Yin and Yang and formed into objects and lives. Yin is the receptive and Yang is the active principle, seen in all forms of change and difference such as the annual season cycles, the natural landscape, the formation of both men and women as characters, and sociopolitical history. While almost all Taoist organizations make use of it, its principles have influenced Confucian, Neo-Confucian or pan-Chinese theory. One can see this symbol as a decorative element on Taoist organization flags and logos, temple floors, or stitched into clerical robes. According to Song dynasty sources, it originated around the 10th century CE. Previously, a tiger and a dragon had symbolized yin and yang.

Taoist temples may fly square or triangular flags. They typically feature mystical writing or diagrams and are intended to fulfill various functions including providing guidance for the spirits of the dead, bringing good fortune, increasing life span, etc. Other flags and banners may be those of the gods or immortals themselves.

A zigzag with seven stars is sometimes displayed, representing the Big Dipper (or the Bushel, the Chinese equivalent). In the Shang Dynasty of the 2nd millennium BCE, Chinese thought regarded the Big Dipper as a deity, while during the Han Dynasty, it was considered a qi path of the circumpolar god, Taiyi.

Taoist temples in southern China and Taiwan may often be identified by their roofs, which feature dragons and phoenixes made from multicolored ceramic tiles. They also stand for the harmony of yin and yang (with the phoenix representing yin). A related symbol is the flaming pearl, which may be seen on such roofs between two dragons, as well as on the hairpin of a Celestial Master. In general though, Chinese Taoist architecture lacks universal features that distinguish it from other structures.

Practices

Rituals

In ancient times, before the Taoism religion was founded, food would sometimes be set out as a sacrifice to the spirits of the deceased or the gods. This could include slaughtered animals, such as pigs and ducks, or fruit. The Taoist Celestial Master Zhang Taoling rejected food and animal sacrifices to the Gods. He tore apart temples which demanded animal sacrifice and drove away its priests. This rejection of sacrifices has continued into the modern day, as Taoism Temples are not allowed to use animal sacrifices (with the exception of folk temples or local tradition.) Another form of sacrifice involves the burning of joss paper, or hell money, on the assumption that images thus consumed by the fire will reappear—not as a mere image, but as the actual item—in the spirit world, making them available for revered ancestors and departed loved ones. The joss paper is mostly used when memorializing ancestors, such as done during the Qingming festival.

Also on particular holidays, street parades take place. These are lively affairs which invariably involve firecrackers and flower-covered floats broadcasting traditional music. They also variously include lion dances and dragon dances; human-occupied puppets (often of the "Seventh Lord" and "Eighth Lord"), Kungfu-practicing and palanquins carrying god-images. The various participants are not considered performers, but rather possessed by the gods and spirits in question.

Fortune-telling—including astrology, I Ching, and other forms of divination—has long been considered a traditional Taoist pursuit. Mediumship is also widely encountered in some sects. There is an academic and social distinction between martial forms of mediumship (such as tongji) and the spirit-writing that is typically practiced through planchette writing.

Physical cultivation

A recurrent and important element of Taoism are rituals, exercises and substances aiming at aligning oneself spiritually with cosmic forces, at undertaking ecstatic spiritual journeys, or at improving physical health and thereby extending one's life, ideally to the point of immortality. Enlightened and immortal beings are referred to as xian.

A characteristic method aiming for longevity is Taoist alchemy. Already in very early Taoist scriptures—like the Taiping Jing and the Baopuzi—alchemical formulas for achieving immortality were outlined.

A number of martial arts traditions, particularly the ones falling under the category of Neijia (like T'ai Chi Ch'uan, Pa Kwa Chang and Xing Yi Quan) embody Taoist principles to a significant extent, and some practitioners consider their art a means of practicing Taoism.

Society

Adherents

The number of Taoists is difficult to estimate, due to a variety of factors including defining Taoism. According to a survey of religion in China in the year 2010, the number of people practicing some form of Chinese folk religion is near to 950 million (70% of the Chinese). Among these, 173 million (13%) claim an affiliation with Taoist practices. Furthermore, 12 million people claim to be "Taoists", a term traditionally used exclusively for initiates, priests and experts of Taoist rituals and methods.

Most Chinese people and many others have been influenced in some way by Taoist traditions. Since the creation of the People's Republic of China, the government has encouraged a revival of Taoist traditions in codified settings. In 1956, the Chinese Taoist Association was formed to administer the activities of all registered Taoist orders, and received official approval in 1957. It was disbanded during the Cultural Revolution under Mao Zedong, but was reestablished in 1980. The headquarters of the association are at the Baiyunguan, or White Cloud Temple of Beijing, belonging to the Longmen branch of Quanzhen Taoism. Since 1980, many Taoist monasteries and temples have been reopened or rebuilt, both belonging to the Zhengyi or Quanzhen schools, and clergy ordination has been resumed.

Taoist literature and art has influenced the cultures of Korea, Japan, and Vietnam. Organized Taoism seems not to have attracted a large non-Chinese following until modern times. In Taiwan, 7.5 million people (33% of the population) identify themselves as Taoists. Data collected in 2010 for religious demographics of Hong Kong and Singapore show that, respectively, 14% and 11% of the people of these cities identify as Taoists.

Followers of Taoism are also present in Chinese émigré communities outside Asia. In addition, it has attracted followers with no Chinese heritage. For example, in Brazil there are Taoist temples in São Paulo and Rio de Janeiro which are affiliated with the Taoist Society of China. Membership of these temples is entirely of non-Chinese ancestry.

Art and poetry

Throughout Chinese history, there have been many examples of art being influenced by Taoist thought. Notable painters influenced by Taoism include Wu Wei, Huang Gongwang, Mi Fu, Muqi Fachang, Shitao, Ni Zan, T'ang Mi, and Wang Tseng-tsu. Taoist arts represents the diverse regions, dialects, and time spans that are commonly associated with Taoism. Ancient Taoist art was commissioned by the aristocracy; however, scholars masters and adepts also directly engaged in the art themselves.

Political aspects

Taoism never had a unified political theory. While Huang-Lao's positions justified a strong emperor as the legitimate ruler, the "primitivists" (like in the chapters 8-11 of the Zhuangzi) argued strongly for a radical anarchism. A more moderate position is presented in the Inner Chapters of the Zhuangzi in which the political life is presented with disdain and some kind of pluralism or perspectivism is preferred. The syncretist position in texts like the Huainanzi and some Outer Chapters of the Zhuangzi blended some Taoist positions with Confucian ones.

Relations with other religions and philosophies

Many scholars believe Taoism arose as a countermovement to Confucianism. The philosophical terms Tao and De are indeed shared by both Taoism and Confucianism. Zhuangzi explicitly criticized Confucian and Mohist tenets in his work. In general, Taoism rejects the Confucian emphasis on rituals, hierarchical social order, and conventional morality, and favors "naturalness", spontaneity, and individualism instead.

The entry of Buddhism into China was marked by significant interaction and syncretism with Taoism. Originally seen as a kind of "foreign Taoism", Buddhism's scriptures were translated into Chinese using the Taoist vocabulary. Representatives of early Chinese Buddhism, like Sengzhao and Tao Sheng, knew and were deeply influenced by the Taoist keystone texts.

Taoism especially shaped the development of Chan (Zen) Buddhism, introducing elements like the concept of naturalness, distrust of scripture and text, and emphasis on embracing "this life" and living in the "every-moment".

On the other hand, Taoism also incorporated Buddhist elements during the Tang dynasty. Examples of such influence include monasteries, vegetarianism, prohibition of alcohol, the doctrine of emptiness, and collecting scripture in tripartite organization in certain sects.

Ideological and political rivals for centuries, Taoism, Confucianism, and Buddhism deeply influenced one another. For example, Wang Bi, one of the most influential philosophical commentators on Lao Tzu (and the I Ching), was a Confucian. The three rivals also share some similar values, with all three embracing a humanist philosophy emphasizing moral behaviour and human perfection. In time, most Chinese people identified to some extent with all three traditions simultaneously. This became institutionalized when aspects of the three schools were synthesized in the Neo-Confucian school.

Some authors have undertaken comparative studies between Taoism and Christianity. This has been of interest for students of history of religion such as J. J. M. de Groot, among others. The comparison of the teachings of Lao Tzu and Jesus of Nazareth has been done by several authors such as Martin Aronson, and Toropov & Hansen (2002), who believe that they have parallels that should not be ignored. In the opinion of J. Isamu Yamamoto the main difference is that Christianity preaches a personal God while Taoism does not. Yet, a number of authors, including Lin Yutang, have argued that some moral and ethical tenets of these religions are similar. In neighboring Vietnam, Taoist values have been shown to adapt to social norms and formed emerging sociocultural beliefs together with Confucianism.