A flower, sometimes known as a bloom or blossom, is the reproductive structure found in flowering plants (plants of the division Magnoliophyta, also called angiosperms). The biological function of a flower is to facilitate reproduction, usually by providing a mechanism for the union of sperm with eggs. Flowers may facilitate outcrossing (fusion of sperm and eggs from different individuals in a population) resulting from cross-pollination or allow selfing (fusion of sperm and egg from the same flower) when self-pollination occurs.

The two types of pollination are: self-pollination and cross-pollination. Self-pollination happens when the pollen from the anther is deposited on the stigma of the same flower, or another flower on the same plant. Cross-pollination is the transfer of pollen from the anther of one flower to the stigma of another flower on a different individual of the same species. Self-pollination happens in flowers where the stamen and carpel mature at the same time, and are positioned so that the pollen can land on the flower's stigma. This pollination does not require an investment from the plant to provide nectar and pollen as food for pollinators.

Some flowers produce diaspores without fertilization (parthenocarpy). Flowers contain sporangia and are the site where gametophytes develop. Many flowers have evolved to be attractive to animals, so as to cause them to be vectors for the transfer of pollen. After fertilization, the ovary of the flower develops into fruit containing seeds.

In addition to facilitating the reproduction of flowering plants, flowers have long been admired and used by humans to bring beauty to their environment, and also as objects of romance, ritual, esotericism, witchcraft, religion, medicine, and as a source of food.

Etymology

Flower is from the Middle English flour, which referred to both the ground grain and the reproductive structure in plants, before splitting off in the 17th century. It comes originally from the Latin name of the Italian goddess of flowers, Flora. The early word for flower in English was blossom, though it now refers to flowers only of fruit trees.

Morphology

Parts

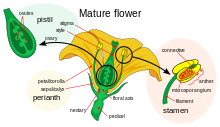

The flower has two essential parts: the vegetative part, consisting of petals and associated structures in the perianth, and the reproductive or sexual parts. A stereotypical flower consists of four kinds of structures attached to the tip of a short stalk. Each of these kinds of parts is arranged in a whorl on the receptacle. The four main whorls (starting from the base of the flower or lowest node and working upwards) are as follows:

Perianth

Collectively the calyx and corolla form the perianth (see diagram).

- Calyx: The calyx consists of leaf-like structures at the base of a flower that protect the flower during development. The leaf-like structures are individually referred to as sepals. There are often as many of these sepals as there are petals. While most calyces are green, there are exceptions in which the calyx is the same color as the petals of the flower or a different color altogether. The calyx performs a crucial role for the flowering plant. As the flower is forming, it is closed tightly into a bud. The sepals are the outer covering of the flower as it forms and are the only thing you see of the flower while it is still in bud form. It protects the developing flower and prevents it from drying out.

- Corolla: the next whorl toward the apex, composed of units called petals, which are typically thin, soft and colored to attract animals that help the process of pollination.

- Perigone: in monocots the calyx and corolla are indistinguishable thus the whorls of the perianth or perigone are called tepals.

Reproductive

- Androecium (from Greek andros oikia: man's house): the next whorl (sometimes multiplied into several whorls), consisting of units called stamens. Stamens consist of two parts: a stalk called a filament, topped by an anther where pollen is produced by meiosis and eventually dispersed.

- Gynoecium (from Greek gynaikos oikia: woman's house): the innermost whorl of a flower, consisting of one or more units called carpels. The carpel or multiple fused carpels form a hollow structure called an ovary, which produces ovules internally. Ovules are megasporangia and they in turn produce megaspores by meiosis which develop into female gametophytes. These give rise to egg cells. The gynoecium of a flower is also described using an alternative terminology wherein the structure one sees in the innermost whorl (consisting of an ovary, style and stigma) is called a pistil. A pistil may consist of a single carpel or a number of carpels fused together. The sticky tip of the pistil, the stigma, is the receptor of pollen. The supportive stalk, the style, becomes the pathway for pollen tubes to grow from pollen grains adhering to the stigma. The relationship to the gynoecium on the receptacle is described as hypogynous (beneath a superior ovary), perigynous (surrounding a superior ovary), or epigynous (above inferior ovary).

Structure

Although the arrangement described above is considered "typical", plant species show a wide variation in floral structure. These modifications have significance in the evolution of flowering plants and are used extensively by botanists to establish relationships among plant species.

The four main parts of a flower are generally defined by their positions on the receptacle and not by their function. Many flowers lack some parts or parts that may be modified into other functions and/or look like what is typically another part. In some families, like Ranunculaceae, the petals are greatly reduced and in many species, the sepals are colorful and petal-like. Other flowers have modified stamens that are petal-like; the double flowers of Peonies and Roses are mostly petaloid stamens. Flowers show great variation and plant scientists describe this variation in a systematic way to identify and distinguish species.

Specific terminology is used to describe flowers and their parts. Many flower parts are fused together; fused parts originating from the same whorl are connate, while fused parts originating from different whorls are adnate; parts that are not fused are free. When petals are fused into a tube or ring that falls away as a single unit, they are sympetalous (also called gamopetalous). Connate petals may have distinctive regions: the cylindrical base is the tube, the expanding region is the throat and the flaring outer region is the limb. A sympetalous flower, with bilateral symmetry with an upper and lower lip, is bilabiate. Flowers with connate petals or sepals may have various shaped corolla or calyx, including campanulate, funnelform, tubular, urceolate, salverform, or rotate.

Referring to "fusion," as it is commonly done, appears questionable because at least some of the processes involved may be non-fusion processes. For example, the addition of intercalary growth at or below the base of the primordia of floral appendages such as sepals, petals, stamens and carpels may lead to a common base that is not the result of fusion.

Many flowers have some form of symmetry. When the perianth is bisected through the central axis from any point and symmetrical halves are produced, the flower is said to be actinomorphic or regular, e.g. rose or trillium. This is an example of radial symmetry. When flowers are bisected and produce only one line that produces symmetrical halves, the flower is said to be irregular or zygomorphic, e.g. snapdragon or most orchids.

Flowers may be directly attached to the plant at their base (sessile—the supporting stalk or stem is highly reduced or absent). The stem or stalk subtending a flower is called a peduncle. If a peduncle supports more than one flower, the stems connecting each flower to the main axis are called pedicels. The apex of a flowering stem forms a terminal swelling which is called the torus or receptacle.

Inflorescence

In those species that have more than one flower on an axis, the collective cluster of flowers is termed an inflorescence. Some inflorescences are composed of many small flowers arranged in a formation that resembles a single flower. The common example of this is most members of the very large composite (Asteraceae) group. A single daisy or sunflower, for example, is not a flower but a flower head—an inflorescence composed of numerous flowers (or florets). An inflorescence may include specialized stems and modified leaves known as bracts.

Diagrams and formulae

A floral formula is a way to represent the structure of a flower using specific letters, numbers and symbols, presenting substantial information about the flower in a compact form. It can represent a taxon, usually giving ranges of the numbers of different organs, or particular species. Floral formulae have been developed in the early 19th century and their use has declined since. Prenner et al. (2010) devised an extension of the existing model to broaden the descriptive capability of the formula. The format of floral formulae differs in different parts of the world, yet they convey the same information.

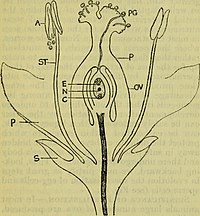

The structure of a flower can also be expressed by the means of floral diagrams. The use of schematic diagrams can replace long descriptions or complicated drawings as a tool for understanding both floral structure and evolution. Such diagrams may show important features of flowers, including the relative positions of the various organs, including the presence of fusion and symmetry, as well as structural details.

Development

A flower develops on a modified shoot or axis from a determinate apical meristem (determinate meaning the axis grows to a set size). It has compressed internodes, bearing structures that in classical plant morphology are interpreted as highly modified leaves. Detailed developmental studies, however, have shown that stamens are often initiated more or less like modified stems (caulomes) that in some cases may even resemble branchlets. Taking into account the whole diversity in the development of the androecium of flowering plants, we find a continuum between modified leaves (phyllomes), modified stems (caulomes), and modified branchlets (shoots).

Transition

The transition to flowering is one of the major phase changes that a plant makes during its life cycle. The transition must take place at a time that is favorable for fertilization and the formation of seeds, hence ensuring maximal reproductive success. To meet these needs a plant is able to interpret important endogenous and environmental cues such as changes in levels of plant hormones and seasonable temperature and photoperiod changes. Many perennial and most biennial plants require vernalization to flower. The molecular interpretation of these signals is through the transmission of a complex signal known as florigen, which involves a variety of genes, including Constans, Flowering Locus C and Flowering Locus T. Florigen is produced in the leaves in reproductively favorable conditions and acts in buds and growing tips to induce a number of different physiological and morphological changes.

The first step of the transition is the transformation of the vegetative stem primordia into floral primordia. This occurs as biochemical changes take place to change cellular differentiation of leaf, bud and stem tissues into tissue that will grow into the reproductive organs. Growth of the central part of the stem tip stops or flattens out and the sides develop protuberances in a whorled or spiral fashion around the outside of the stem end. These protuberances develop into the sepals, petals, stamens, and carpels. Once this process begins, in most plants, it cannot be reversed and the stems develop flowers, even if the initial start of the flower formation event was dependent of some environmental cue.

Organ development

The ABC model is a simple model that describes the genes responsible for the development of flowers. Three gene activities interact in a combinatorial manner to determine the developmental identities of the primordia organ within the floral apical meristem. These gene functions are called A, B, and C. A genes are expressed in only outer and lower most section of the apical meristem, which becomes a whorl of sepals. In the second whorl both A and B genes are expressed, leading to the formation of petals. In the third whorl, B and C genes interact to form stamens and in the center of the flower C genes alone give rise to carpels. The model is based upon studies of aberrant flowers and mutations in Arabidopsis thaliana and the snapdragon, Antirrhinum majus. For example, when there is a loss of B gene function, mutant flowers are produced with sepals in the first whorl as usual, but also in the second whorl instead of the normal petal formation. In the third whorl the lack of B function but presence of C function mimics the fourth whorl, leading to the formation of carpels also in the third whorl.

Function

The principal purpose of a flower is the reproduction of the individual and the species. All flowering plants are heterosporous, that is, every individual plant produces two types of spores. Microspores are produced by meiosis inside anthers and megaspores are produced inside ovules that are within an ovary. Anthers typically consist of four microsporangia and an ovule is an integumented megasporangium. Both types of spores develop into gametophytes inside sporangia. As with all heterosporous plants, the gametophytes also develop inside the spores, i. e., they are endosporic.

In the majority of plant species, individual flowers have both functional carpels and stamens. Botanists describe these flowers as perfect or bisexual, and the species as hermaphroditic. In a minority of plant species, their flowers lack one or the other reproductive organ and are described as imperfect or unisexual. If the individual plants of a species each have unisexual flowers of both sexes then the species is monoecious. Alternatively, if each individual plant has only unisexual flowers of the same sex then the species is dioecious.

Pollination

The primary purpose of the flower is reproduction. Since the flowers are the reproductive organs of the plant, they mediate the joining of the sperm, contained within pollen, to the ovules — contained in the ovary. Pollination is the movement of pollen from the anthers to the stigma. Normally pollen is moved from one plant to another, known as cross-pollination, but many plants are able to self-pollinate. Cross-pollination is preferred because it allows for genetic variation, which contributes to the survival of the species. Many flowers are dependent, then, upon external factors for pollination, such as: the wind, water, animals, and especially insects. Larger animals such as birds, bats, and even some pygmy possums, however, can also be employed. To accomplish this, flowers have specific designs which encourage the transfer of pollen from one plant to another of the same species. The period of time during which this process can take place (when the flower is fully expanded and functional) is called anthesis, hence the study of pollination biology is called anthecology.

Flowering plants usually face evolutionary pressure to optimize the transfer of their pollen, and this is typically reflected in the morphology of the flowers and the behaviour of the plants. Pollen may be transferred between plants via a number of 'vectors,' or methods. Around 80% of flowering plants make use of biotic, or living vectors. Others use abiotic, or non-living, vectors and some plants make use of multiple vectors, but most are highly specialised.

Though some fit between or outside of these groups, most flowers can be divided between the following two broad groups of pollination methods:

Biotic pollination

Flowers that use biotic vectors attract and use insects, bats, birds, or other animals to transfer pollen from one flower to the next. Often they are specialized in shape and have an arrangement of the stamens that ensures that pollen grains are transferred to the bodies of the pollinator when it lands in search of its attractant (such as nectar, pollen, or a mate). In pursuing this attractant from many flowers of the same species, the pollinator transfers pollen to the stigmas—arranged with equally pointed precision—of all of the flowers it visits. Many flowers rely on simple proximity between flower parts to ensure pollination, while others have elaborate designs to ensure pollination and prevent self-pollination. Flowers use animals including: insects (entomophily), birds (ornithophily), bats (chiropterophily), lizards, and even snails and slugs (malacophilae).

Attraction methods

Plants cannot move from one location to another, thus many flowers have evolved to attract animals to transfer pollen between individuals in dispersed populations. Most commonly, flowers are insect-pollinated, known as entomophilous; literally "insect-loving" in Greek. To attract these insects flowers commonly have glands called nectaries on various parts that attract animals looking for nutritious nectar. Birds and bees have color vision, enabling them to seek out "colorful" flowers. Some flowers have patterns, called nectar guides, that show pollinators where to look for nectar; they may be visible only under ultraviolet light, which is visible to bees and some other insects.

Flowers also attract pollinators by scent, though not all flower scents are appealing to humans; a number of flowers are pollinated by insects that are attracted to rotten flesh and have flowers that smell like dead animals. These are often called Carrion flowers, including plants in the genus Rafflesia, and the titan arum. Flowers pollinated by night visitors, including bats and moths, are likely to concentrate on scent to attract pollinators and so most such flowers are white.

Flowers are also specialized in shape and have an arrangement of the stamens that ensures that pollen grains are transferred to the bodies of the pollinator when it lands in search of its attractant. Other flowers use mimicry or pseudocopulation to attract pollinators. Many orchids for example, produce flowers resembling female bees or wasps in colour, shape, and scent. Males move from one flower to the next in search of a mate, pollinating the flowers.

Pollinator relationships

Many flowers have close relationships with one or a few specific pollinating organisms. Many flowers, for example, attract only one specific species of insect, and therefore rely on that insect for successful reproduction. This close relationship an example of coevolution, as the flower and pollinator have developed together over a long period of time to match each other's needs. This close relationship compounds the negative effects of extinction, however, since the extinction of either member in such a relationship would almost certainly mean the extinction of the other member as well.

Abiotic pollination

Flowers that use abiotic, or non-living, vectors use the wind or, much less commonly, water, to move pollen from one flower to the next. In wind-dispersed (anemophilous) species, the tiny pollen grains are carried, sometimes many thousands of kilometres, by the wind to other flowers. Common examples include the grasses, birch trees, along with many other species in the order fagales, ragweeds, and many sedges. They have no need to attract pollinators and therefore tend not to grow large, showy, or colorful flowers, and do not have nectaries, nor a noticeable scent. Because of this, plants typically have many thousands of tiny flowers which have comparatively large, feathery stigmas; to increase the chance of pollen being received. Whereas the pollen of entomophilous flowers is usually large, sticky, and rich in protein (to act as a "reward" for pollinators), anemophilous flower pollen is typically small-grained, very light, smooth, and of little nutritional value to insects. In order for the wind to effectively pick up and transport the pollen, the flowers typically have anthers loosely attached to the end of long thin filaments, or pollen forms around a catkin which moves in the wind. Rarer forms of this involve individual flowers being moveable by the wind (Pendulous), or even less commonly; the anthers exploding to release the pollen into the wind.

Pollination through water (hydrophily) is a much rarer method, occurring in only around 2% of abiotically-pollinated flowers. Common examples of this include Calitriche autumnalis, Vallisneria spiralis and some sea-grasses. One characteristic which most species in this group share is a lack of an exine, or protective layer, around the pollen grain. Paul Knuth identified two types of hydrophilous pollination in 1906 and Ernst Schwarzenbach added a third in 1944. Knuth named his two groups Hyphydrogamy and the more common Ephydrogamy. In Hyphydrogamy pollination occurs below the surface of the water and so the pollen grains are typically negatively buoyant. For marine plants that exhibit this method the stigmas are usually stiff, while freshwater species have small and feathery stigmas. In Ephydrogamy pollination occurs on the surface of the water and so the pollen has a low density to enable floating, though many also use rafts, and are hydrophobic. Marine flowers have floating thread-like stigmas and may have adaptations for the tide, while freshwater species create indentations in the water. The third category, set out by Schwarzenbach, is those flowers which transport pollen above the water through conveyance. This ranges from floating plants, (Lemnoideae), to staminate flowers (Vallisneria). Most species in this group have dry, spherical pollen which sometimes forms into larger masses, and female flowers which form depressions in the water; the method of transport varies.

Mechanisms

Flowers can be pollinated by two mechanisms; cross-pollination and self-pollination. No mechanism is indisputably better than the other as they each have their advantages and disadvantages. Plants use one or both of these mechanisms depending on their habitat and ecological niche.

Cross-pollination

Cross-pollination is the pollination of the carpel by pollen from a different plant of the same species. Because the genetic make-up of the sperm contained within the pollen from the other plant is different, their combination will result in a new, genetically distinct, plant, through the process of sexual reproduction. Since each new plant is genetically distinct, the different plants show variation in their physiological and structural adaptations and so the population as a whole is better prepared for an adverse occurrence in the environment. Cross-pollination, therefore, increases the survival of the species and is usually preferred by flowers for this reason.

Self-pollination

Self-pollination is the pollination of the carpel of a flower by pollen from either the same flower or another flower on the same plant, leading to the creation of a genetic clone through asexual reproduction. This increases the reliability of producing seeds, the rate at which they can be produced, and lowers the amount energy needed. But, most importantly, it limits genetic variation. The extreme case of self-fertilization, when the ovule is fertilized by pollen from the same flower or plant, occurs in flowers that always self-fertilize, such as many dandelions. Some flowers are self-pollinated and have flowers that never open or are self-pollinated before the flowers open; these flowers are called cleistogamous; many species in the genus Viola exhibit this, for example. Conversely, many species of plants have ways of preventing self-pollination and hence, self-fertilization. Unisexual male and female flowers on the same plant may not appear or mature at the same time, or pollen from the same plant may be incapable of fertilizing its ovules. The latter flower types, which have chemical barriers to their own pollen, are referred to as self-incompatible. In Clianthus puniceus, (pictured), self-pollination is used strategically as an "insurance policy." When a pollinator, in this case a bird, visits C. puniceus it rubs off the stigmatic covering and allows for pollen from the bird to enter the stigma. If no pollinators visit, however, then the stigmatic covering falls off naturally to allow for the flower's own anthers to pollinate the flower through self-pollination.

Allergies

Pollen is a large contributor to asthma and other respiratory allergies which combined affect between 10 and 50% of people worldwide. This number appears to be growing, as the temperature increases due to climate change mean that plants are producing more pollen, which is also more allergenic. Pollen is difficult to avoid, however, because of its small size and prevalence in the natural environment. Most of the pollen which causes allergies is that produced by wind-dispersed pollinators such as the grasses, birch trees, oak trees, and ragweeds; the allergens in pollen are proteins which are thought to be necessary in the process of pollination.

Fertilization

Fertilization, also called Synagmy, occurs following pollination, which is the movement of pollen from the stamen to the carpel. It encompasses both plasmogamy, the fusion of the protoplasts, and karyogamy, the fusion of the nuclei. When pollen lands on the stigma of the flower it begins creating a pollen tube which runs down through the style and into the ovary. After penetrating the centre-most part of the ovary it enters the egg apparatus and into one synergid. At this point the end of the pollen tube bursts and releases the two sperm cells, one of which makes its way to an egg, while also losing its cell membrane and much of its protoplasm. The sperm's nucleus then fuses with the egg's nucleus, resulting in the formation of a zygote, a diploid (two copies of each chromosome) cell.

Whereas in fertilization only plasmogamy, or the fusion of the whole sex cells, results, in Angiosperms (flowering plants) a process known as double fertilization, which involves both karyogamy and plasmogamy, occurs. In double fertilization the second sperm cell subsequently also enters the synergid and fuses with the two polar nuclei of the central cell. Since all three nuclei are haploid, they result in a large endosperm nucleus which is triploid.

Seed development

Following the formation of zygote it begins to grow through nuclear and cellular divisions, called mitosis, eventually becoming a small group of cells. One section of it becomes the embryo, while the other becomes the suspensor; a structure which forces the embryo into the endosperm and is later undetectable. Two small primordia also form at this time, that later become the cotyledon, which is used as an energy store. Plants which grow out one of these primordia are called monocotyledons, while those that grow out two are dicotyledons. The next stage is called the Torpedo stage and involves the growth of several key structures, including: the radicle (embryotic root), the epicotyl (embryotic stem), and the hypocotyl, (the root/shoot junction). In the final step vascular tissue develops around the seed.

Fruit development

The ovary, inside which the seed is forming from the ovule, grows into a fruit. All the other main floral parts die during this development, including: the style, stigma, sepals, stamens, and petals. The fruit contains three structures: the exocarp, or outer layer, the mesocarp, or the fleshy part, and the endocarp, or innermost layer, while the fruit wall is called the pericarp. The size, shape, toughness, and thickness varies among different fruit. The size, shape, toughness, and thickness varies among different fruit. This is because it is directly connected to the method of seed dispersal; that being the purpose of fruit - to encourage or enable the seed's dispersal and protect the seed while doing so.

Seed dispersal

Following the pollination of a flower, fertilization, and finally the development of a seed and fruit, a mechanism is typically used to disperse the fruit away from the plant. In Angiosperms (flowering plants) seeds are dispersed away from the plant so as to not force competition between the mother and the daughter plants, as well as to enable the colonisation of new areas. They are often divided into two categories, though many plants fall in between or in one or more of these:

Allochory

In allochory, plants use an external vector, or carrier, to transport their seeds away from them. These can be either biotic (living), such as by birds and ants, or abiotic (non-living), such as by the wind or water.[70][71][72]

Biotic vectors

Many plants use biotic vectors to disperse their seeds away from them. This method falls under the umbrella term Zoochory, while Endozoochory, also known as fruigivory, refers specifically to plants adapted to grow fruit in order to attract animals to eat them. Once eaten they go through typically go through animal's digestive system and are dispersed away from the plant. Some seeds are specially adapted either to last in the gizzard of animals or even to germinate better after passing through them. They can be eaten by birds (ornithochory), bats (chiropterochory), rodents, primates, ants (myrmecochory), non-bird sauropsids (saurochory), mammals in general (mammaliochory), and even fish. Typically their fruit are fleshy, have a high nutritional value, and may have chemical attractants as an additional "reward" for dispersers. This is reflected morphologically in the presence of more pulp, an aril, and sometimes an elaiosome (primarily for ants), which are other fleshy structures. Epizoochory occurs in plants whose seeds are adapted to cling on to animals and be dispersed that way, such as many species in the genus Acaena. Typically these plants seed's have hooks or a viscous surface to easier grip to animals, which include birds and animals with fur. Some plants use mimesis, or imitation, to trick animals into dispersing the seeds and these often have specially adapted colors. The final type of Zoochory is called Synzoochory, which involves neither the digestion of the seeds, nor the unintentional carrying of the seed on the body, but the deliberate carrying of the seeds by the animals. This is usually in the mouth or beak of the animal (called Stomatochory), which is what is used for many birds and all ants.

Abiotic vectors

In abiotic dispersal plants use the vectors of the wind, water, or a mechanism of their own to transport their seeds away from them. Anemochory involves using the wind as a vector to disperse plant's seeds. Because these seeds have to travel in the wind they are almost always small - sometimes even dust-like, have a high surface-area-to-volume ratio, and are produced in a large number - sometimes up to a million. Plants such as tumbleweeds detach the entire shoot to let the seeds roll away with the wind. Another common adaptation are wings, plumes or balloon like structures that let the seeds stay in the air for longer and hence travel farther. In Hydrochory plants are adapted to disperse their seeds through bodies of water and so typically are buoyant and have a low relative density with regards to the water. Commonly seeds are adapted morphologically with hydrophobic surfaces, small size, hairs, slime, oil, and sometimes air spaces within the seeds. These plants fall into three categories: ones where seeds are dispersed on the surface of water currents, under the surface of water currents, and by rain landing on a plant.

Autochory

In autochory, plants create their own vectors to transport the seeds away from them. Adaptations for this usually involve the fruits exploding and forcing the seeds away ballistically, such as in Hura crepitans, or sometimes in the creation of creeping diaspores. Because of the relatively small distances that these methods can disperse their seeds, they are often paired with an external vector.

Evolution

−4500 — – — – −4000 — – — – −3500 — – — – −3000 — – — – −2500 — – — – −2000 — – — – −1500 — – — – −1000 — – — – −500 — – — – 0 — |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

While land plants have existed for about 425 million years, the first ones reproduced by a simple adaptation of their aquatic counterparts: spores. In the sea, plants—and some animals—can simply scatter out genetic clones of themselves to float away and grow elsewhere. This is how early plants reproduced. But plants soon evolved methods of protecting these copies to deal with drying out and other damage which is even more likely on land than in the sea. The protection became the seed, though it had not yet evolved the flower. Early seed-bearing plants include the ginkgo and conifers.

Several groups of extinct gymnosperms, particularly seed ferns, have been proposed as the ancestors of flowering plants but there is no continuous fossil evidence showing exactly how flowers evolved. The apparently sudden appearance of relatively modern flowers in the fossil record posed such a problem for the theory of evolution that it was called an "abominable mystery" by Charles Darwin.

Recently discovered angiosperm fossils such as Archaefructus, along with further discoveries of fossil gymnosperms, suggest how angiosperm characteristics may have been acquired in a series of steps. An early fossil of a flowering plant, Archaefructus liaoningensis from China, is dated about 125 million years old. Even earlier from China is the 125–130 million years old Archaefructus sinensis. In 2015 a plant (130 million-year-old Montsechia vidalii, discovered in Spain) was claimed to be 130 million years old. In 2018, scientists reported that the earliest flowers began about 180 million years ago.

Recent DNA analysis (molecular systematics) shows that Amborella trichopoda, found on the Pacific island of New Caledonia, is the only species in the sister group to the rest of the flowering plants, and morphological studies suggest that it has features which may have been characteristic of the earliest flowering plants.

Besides the hard proof of flowers in or shortly before the Cretaceous, there is some circumstantial evidence of flowers as much as 250 million years ago. A chemical used by plants to defend their flowers, oleanane, has been detected in fossil plants that old, including gigantopterids, which evolved at that time and bear many of the traits of modern, flowering plants, though they are not known to be flowering plants themselves, because only their stems and prickles have been found preserved in detail; one of the earliest examples of petrification.

The similarity in leaf and stem structure can be very important, because flowers are genetically just an adaptation of normal leaf and stem components on plants, a combination of genes normally responsible for forming new shoots. The most primitive flowers are thought to have had a variable number of flower parts, often separate from (but in contact with) each other. The flowers would have tended to grow in a spiral pattern, to be bisexual (in plants, this means both male and female parts on the same flower), and to be dominated by the ovary (female part). As flowers grew more advanced, some variations developed parts fused together, with a much more specific number and design, and with either specific sexes per flower or plant, or at least "ovary inferior".

The general assumption is that the function of flowers, from the start, was to involve animals in the reproduction process. Pollen can be scattered without bright colors and obvious shapes, which would therefore be a liability, using the plant's resources, unless they provide some other benefit. One proposed reason for the sudden, fully developed appearance of flowers is that they evolved in an isolated setting like an island, or chain of islands, where the plants bearing them were able to develop a highly specialized relationship with some specific animal (a wasp, for example), the way many island species develop today. This symbiotic relationship, with a hypothetical wasp bearing pollen from one plant to another much the way fig wasps do today, could have eventually resulted in both the plant(s) and their partners developing a high degree of specialization. Island genetics is believed to be a common source of speciation, especially when it comes to radical adaptations which seem to have required inferior transitional forms. Note that the wasp example is not incidental; bees, apparently evolved specifically for symbiotic plant relationships, are descended from wasps.

Likewise, most fruit used in plant reproduction comes from the enlargement of parts of the flower. This fruit is frequently a tool which depends upon animals wishing to eat it, and thus scattering the seeds it contains.

While many such symbiotic relationships remain too fragile to survive competition with mainland organisms, flowers proved to be an unusually effective means of production, spreading (whatever their actual origin) to become the dominant form of land plant life.

Flower evolution continues to the present day; modern flowers have been so profoundly influenced by humans that many of them cannot be pollinated in nature. Many modern, domesticated flowers used to be simple weeds, which only sprouted when the ground was disturbed. Some of them tended to grow with human crops, and the prettiest did not get plucked because of their beauty, developing a dependence upon and special adaptation to human affection.

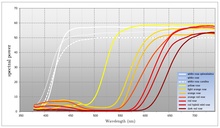

Colour

Many flowering plants reflect as much light as possible within the range of visible wavelengths of the pollinator the plant intends to attract. Flowers that reflect the full range of visible light are generally perceived as white by a human observer. An important feature of white flowers is that they reflect equally across the visible spectrum. While many flowering plants use white to attract pollinators, the use of color is also widespread (even within the same species). Color allows a flowering plant to be more specific about the pollinator it seeks to attract. The color model used by human color reproduction technology (CMYK) relies on the modulation of pigments that divide the spectrum into broad areas of absorption. Flowering plants by contrast are able to shift the transition point wavelength between absorption and reflection. If it is assumed that the visual systems of most pollinators view the visible spectrum as circular then it may be said that flowering plants produce color by absorbing the light in one region of the spectrum and reflecting the light in the other region. With CMYK, color is produced as a function of the amplitude of the broad regions of absorption. Flowering plants by contrast produce color by modifying the frequency (or rather wavelength) of the light reflected. Most flowers absorb light in the blue to yellow region of the spectrum and reflect light from the green to red region of the spectrum. For many species of flowering plant, it is the transition point that characterizes the color that they produce. Color may be modulated by shifting the transition point between absorption and reflection and in this way a flowering plant may specify which pollinator it seeks to attract. Some flowering plants also have a limited ability to modulate areas of absorption. This is typically not as precise as control over wavelength. Humans observers will perceive this as degrees of saturation (the amount of white in the color).

Classical taxonomy

In plant taxonomy, which is the study of the classification and identification of plants, the morphology of plant's flowers are used extensively – and have been for thousands of years. Although the history of plant taxonomy extends back to at least around 300 B.C. with the writings of Theophrastus, the foundation of the modern science is based on works in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778), was a Swedish botanist who spent most of his working life as a professor of natural history. His landmark 1757 book Species Plantarum lays out his system of classification as well as the concept of binomial nomenclature, the latter of which is still used around the world today. He identified 24 classes, based mainly on the number, length and union of the stamens. The first ten classes follow the number of stamens directly (Octandria have 8 stamens etc.), while class eleven has 11-20 stamens and classes twelve and thirteen have 20 stamens; differing only in their point of attachment. The next five classes deal with the length of the stamens and the final five with the nature of the reproductive capability of the plant; where the stamen grows; and if the flower is concealed or exists at all (such as in ferns). This method of classification, despite being artificial, was used extensively for the following seven decades, before being replaced by the system of another botanist.

Antoine Laurent de Jussieu (1748–1836) was a French botanist whose 1787 work Genera plantarum: secundum ordines naturales disposita set out a new method for classifying plants; based instead on natural characteristics. Plants were divided by the number, if any, of cotyledons, and the location of the stamens. The next most major system of classification came in the late 19th century from the botanists Joseph Dalton Hooker (1817–1911) and George Bentham (1800–1884). They built on the earlier works of de Jussieu and Augustin Pyramus de Candolle and devised a system which is still used in many of the world's herbaria. Plants were divided at the highest level by the number of cotyledons and the nature of the flowers, before falling into orders (families), genera, and species. This system of classification was published in their Genera plantarum in three volumes between 1862 and 1883. It is the most highly regarded and deemed the "best system of classification," in some settings.

Following the development in scientific thought after Darwin's On the Origin of Species, many botanists have used more phylogenetic methods and the use of genetic sequencing, cytology, and palynology has become increasingly common. Despite this, morphological characteristics such as the nature of the flower and inflorescence still make up the bedrock of plant taxonomy.

Symbolism

Many flowers have important symbolic meanings in Western culture. The practice of assigning meanings to flowers is known as floriography. Some of the more common examples include:

- Red roses are given as a symbol of love, beauty, and passion.

- Poppies are a symbol of consolation in time of death. In the United Kingdom, New Zealand, Australia and Canada, red poppies are worn to commemorate soldiers who have died in times of war.

- Irises/Lily are used in burials as a symbol referring to "resurrection/life". It is also associated with stars (sun) and its petals blooming/shining.

- Daisies are a symbol of innocence.

Because of their varied and colorful appearance, flowers have long been a favorite subject of visual artists as well. Some of the most celebrated paintings from well-known painters are of flowers, such as Van Gogh's sunflowers series or Monet's water lilies. Flowers are also dried, freeze dried and pressed in order to create permanent, three-dimensional pieces of floral art.

Flowers within art are also representative of the female genitalia, as seen in the works of artists such as Georgia O'Keeffe, Imogen Cunningham, Veronica Ruiz de Velasco, and Judy Chicago, and in fact in Asian and western classical art. Many cultures around the world have a marked tendency to associate flowers with femininity.

The great variety of delicate and beautiful flowers has inspired the works of numerous poets, especially from the 18th–19th century Romantic era. Famous examples include William Wordsworth's I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud and William Blake's Ah! Sun-Flower.

Their symbolism in dreams has also been discussed, with possible interpretations including "blossoming potential".

The Roman goddess of flowers, gardens, and the season of Spring is Flora. The Greek goddess of spring, flowers and nature is Chloris.

In Hindu mythology, flowers have a significant status. Vishnu, one of the three major gods in the Hindu system, is often depicted standing straight on a lotus flower. Apart from the association with Vishnu, the Hindu tradition also considers the lotus to have spiritual significance. For example, it figures in the Hindu stories of creation.

Human use

History shows that flowers have been used by humans for thousands of years, to serve a variety of purposes. An early example of this is from about 4,500 years ago in Ancient Egypt, where flowers would be used to decorate women's hair. Flowers have also inspired art time and time again, such as in Monet's Water Lilies or William Wordsworth’s poem about daffodils entitled: "I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud."

In modern times, people have sought ways to cultivate, buy, wear, or otherwise be around flowers and blooming plants, partly because of their agreeable appearance and smell. Around the world, people use flowers to mark important events in their lives:

- For new births or christenings

- As a corsage or boutonniere worn at social functions or for holidays

- As tokens of love or esteem

- For wedding flowers for the bridal party, and for decorations for the hall

- As brightening decorations within the home

- As a gift of remembrance for bon voyage parties, welcome-home parties, and "thinking of you" gifts

- For funeral flowers and expressions of sympathy for the grieving

- For worship. In Christianity, chancel flowers often adorn churches. In Hindu culture, adherents commonly bring flowers as a gift to temples

People therefore grow flowers around their homes, dedicate parts of their living space to flower gardens, pick wildflowers, or buy commercially-grown flowers from florists.

Flowers provide less food than other major plant parts (seeds, fruits, roots, stems and leaves), but still provide several important vegetables and spices. Flower vegetables include broccoli, cauliflower and artichoke. The most expensive spice, saffron, consists of dried stigmas of a crocus. Other flower spices are cloves and capers. Hops flowers are used to flavor beer. Marigold flowers are fed to chickens to give their egg yolks a golden yellow color, which consumers find more desirable; dried and ground marigold flowers are also used as a spice and colouring agent in Georgian cuisine. Flowers of the dandelion and elder are often made into wine. Bee pollen, pollen collected from bees, is considered a health food by some people. Honey consists of bee-processed flower nectar and is often named for the type of flower, e.g. orange blossom honey, clover honey and tupelo honey.

Hundreds of fresh flowers are edible, but only few are widely marketed as food. They are often added to salads as garnishes. Squash blossoms are dipped in breadcrumbs and fried. Some edible flowers include nasturtium, chrysanthemum, carnation, cattail, Japanese honeysuckle, chicory, cornflower, canna, and sunflower. Edible flowers such as daisy, rose, and violet are sometimes candied.

Flowers such as chrysanthemum, rose, jasmine, Japanese honeysuckle, and chamomile, chosen for their fragrance and medicinal properties, are used as tisanes, either mixed with tea or on their own.

Flowers have been used since prehistoric times in funeral rituals: traces of pollen have been found on a woman's tomb in the El Miron Cave in Spain. Many cultures draw a connection between flowers and life and death, and because of their seasonal return flowers also suggest rebirth, which may explain why many people place flowers upon graves. The ancient Greeks, as recorded in Euripides's play The Phoenician Women, placed a crown of flowers on the head of the deceased; they also covered tombs with wreaths and flower petals. Flowers were widely used in ancient Egyptian burials, and the Mexicans to this day use flowers prominently in their Day of the Dead celebrations in the same way that their Aztec ancestors did.

Giving

The flower-giving tradition goes back to prehistoric times when flowers often had a medicinal and herbal attributes. Archaeologists found in several grave sites remnants of flower petals. Flowers were first used as sacrificial and burial objects. Ancient Egyptians and later Greeks and Romans used flowers. In Egypt, burial objects from the time around 1540 BC were found, which depicted red poppy, yellow Araun, cornflower and lilies. Records of flower giving appear in Chinese writings and Egyptian hieroglyphics, as well as in Greek and Roman mythology. The practice of giving a flower flourished in the Middle Ages when couples showed affection through flowers.

The tradition of flower-giving exists in many forms. It is an important part of Russian culture and folklore. It is common for students to give flowers to their teachers. To give yellow flowers in a romantic relationship means break-up in Russia. Nowadays, flowers are often given away in the form of a flower bouquet.