| History of science and technology in China |

|---|

| By subject |

| By era |

| Alternative medicine |

|---|

|

|

|

Chinese herbology (simplified Chinese: 中药学; traditional Chinese: 中藥學; pinyin: zhōngyào xué) is the theory of traditional Chinese herbal therapy, which accounts for the majority of treatments in traditional Chinese medicine (TCM). A Nature editorial described TCM as "fraught with pseudoscience", and said that the most obvious reason why it has not delivered many cures is that the majority of its treatments have no logical mechanism of action.

The term herbology is misleading in the sense that, while plant elements are by far the most commonly used substances, animal, human, and mineral products are also utilized, among which some are poisonous. In the Huangdi Neijing they are referred to as 毒藥 (pinyin: dúyào) which means toxin, poison, or medicine. Unschuld points out that this is similar etymology to the Greek pharmakon and so he uses the term "pharmaceutic". Thus, the term "medicinal" (instead of herb) is usually preferred as a translation for 药 (pinyin: yào).

Research into the effectiveness of traditional Chinese herbal therapy is of poor quality and often tainted by bias, with little or no rigorous evidence of efficacy. There are concerns over a number of potentially toxic Chinese herbs.

History

Chinese herbs have been used for centuries. Among the earliest literature are lists of prescriptions for specific ailments, exemplified by the manuscript "Recipes for 52 Ailments", found in the Mawangdui which were sealed in 168 BC.

The first traditionally recognized herbalist is Shénnóng (神农, lit. "Divine Farmer"), a mythical god-like figure, who is said to have lived around 2800 BC. He allegedly tasted hundreds of herbs and imparted his knowledge of medicinal and poisonous plants to farmers. His Shénnóng Běn Cǎo Jīng (神农本草经, Shennong's Materia Medica) is considered as the oldest book on Chinese herbal medicine. It classifies 365 species of roots, grass, woods, furs, animals and stones into three categories of herbal medicine:

- The "superior" category, which includes herbs effective for multiple diseases and are mostly responsible for maintaining and restoring the body balance. They have almost no unfavorable side-effects.

- A category comprising tonics and boosters, whose consumption must not be prolonged.

- A category of substances which must usually be taken in small doses, and for the treatment of specific diseases only.

The original text of Shennong's Materia Medica has been lost; however, there are extant translations. The true date of origin is believed to fall into the late Western Han dynasty (i.e., the first century BC).

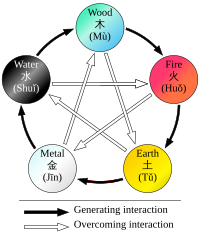

The Treatise on Cold Damage Disorders and Miscellaneous Illnesses was collated by Zhang Zhongjing, also sometime at the end of the Han dynasty, between 196 and 220 CE. Focusing on drug prescriptions, it was the first medical work to combine Yinyang and the Five Phases with drug therapy. This formulary was also the earliest Chinese medical text to group symptoms into clinically useful "patterns" (zheng 證) that could serve as targets for therapy. Having gone through numerous changes over time, it now circulates as two distinct books: the Treatise on Cold Damage Disorders and the Essential Prescriptions of the Golden Casket, which were edited separately in the eleventh century, under the Song dynasty.

Succeeding generations augmented these works, as in the Yaoxing Lun (药性论; 藥性論; 'Treatise on the Nature of Medicinal Herbs'), a 7th-century Tang dynasty Chinese treatise on herbal medicine.

There was a shift in emphasis in treatment over several centuries. A section of the Neijing Suwen including Chapter 74 was added by Wang Bing [王冰 Wáng Bīng] in his 765 edition. In which it says: 主病之謂君,佐君之謂臣,應臣之謂使,非上下三品之謂也。 "Ruler of disease it called Sovereign, aid to Sovereign it called Minister, comply with Minister it called Envoy (Assistant), not upper lower three classes (qualities) it called." The last part is interpreted as stating that these three rulers are not the three classes of Shénnóng mentioned previously. This chapter in particular outlines a more forceful approach. Later on Zhang Zihe [張子和 Zhāng Zĭ-hé, aka Zhang Cong-zhen] (1156–1228) is credited with founding the 'Attacking School' which criticized the overuse of tonics.

Arguably the most important of these later works is the Compendium of Materia Medica (Bencao Gangmu:本草綱目) compiled during the Ming dynasty by Li Shizhen, which is still used today for consultation and reference.

The use of Chinese herbs was popular during the medieval age in western Asian and Islamic countries. They were traded through the Silk Road from the East to the West. Cinnamon, ginger, rhubarb, nutmeg and cubeb are mentioned as Chinese herbs by medieval Islamic medical scholars Such as Rhazes (854– 925 CE), Haly Abbas (930–994 CE) and Avicenna (980–1037 CE). There were also multiple similarities between the clinical uses of these herbs in Chinese and Islamic medicine.

Raw materials

There are roughly 13,000 medicinals used in China and over 100,000 medicinal recipes recorded in the ancient literature. Plant elements and extracts are by far the most common elements used. In the classic Handbook of Traditional Drugs from 1941, 517 drugs were listed – out of these, only 45 were animal parts, and 30 were minerals. For many plants used as medicinals, detailed instructions have been handed down not only regarding the locations and areas where they grow best, but also regarding the best timing of planting and harvesting them.

Some animal parts used as medicinals can be considered rather strange such as cows' gallstones.

Furthermore, the classic materia medica Bencao Gangmu describes the use of 35 traditional Chinese medicines derived from the human body, including bones, fingernail, hairs, dandruff, earwax, impurities on the teeth, feces, urine, sweat, and organs, but most are no longer in use.

Preparation

Decoction

Typically, one batch of medicinals is prepared as a decoction of about 9 to 18 substances. Some of these are considered as main herbs, some as ancillary herbs; within the ancillary herbs, up to three categories can be distinguished. Some ingredients are added in order to cancel out toxicity or side-effects of the main ingredients; on top of that, some medicinals require the use of other substances as catalysts.

Chinese patent medicine

Chinese patent medicine (中成药; 中成藥; zhōngchéng yào) is a kind of traditional Chinese medicine. They are standardized herbal formulas. From ancient times, pills were formed by combining several herbs and other ingredients, which were dried and ground into a powder. They were then mixed with a binder and formed into pills by hand. The binder was traditionally honey. Modern teapills, however, are extracted in stainless steel extractors to create either a water decoction or water-alcohol decoction, depending on the herbs used. They are extracted at a low temperature (below 100 degrees Celsius) to preserve essential ingredients. The extracted liquid is then further condensed, and some raw herb powder from one of the herbal ingredients is mixed in to form an herbal dough. This dough is then machine cut into tiny pieces, a small amount of excipients are added for a smooth and consistent exterior, and they are spun into pills.

These medicines are not patented in the traditional sense of the word. No one has exclusive rights to the formula. Instead, "patent" refers to the standardization of the formula. In China, all Chinese patent medicines of the same name will have the same proportions of ingredients, and manufactured in accordance with the PRC Pharmacopoeia, which is mandated by law. However, in western countries there may be variations in the proportions of ingredients in patent medicines of the same name, and even different ingredients altogether.

Several producers of Chinese herbal medicines are pursuing FDA clinical trials to market their products as drugs in U.S. and European markets.

Chinese herbal extracts

Chinese herbal extracts are herbal decoctions that have been condensed into a granular or powdered form. Herbal extracts, similar to patent medicines, are easier and more convenient for patients to take. The industry extraction standard is 5:1, meaning for every five pounds of raw materials, one pound of herbal extract is derived.

Categorization

There are several different methods to classify traditional Chinese medicinals:

- The Four Natures (四气; 四氣; sìqì)

- The Five Flavors (五味; wǔwèi)

- The meridians (经络; 經絡; jīngluò)

- The specific function.

Four Natures

The Four Natures are: hot (热; 熱), warm (温; 溫), cool (凉), cold (寒) or neutral (平). Hot and warm herbs are used to treat cold diseases, while cool and cold herbs are used to treat hot diseases.

Five Flavors

The Five Flavors, sometimes also translated as Five Tastes, are: acrid/pungent (辛), sweet (甘), bitter (苦), sour (酸), and salty (咸; 鹹). Substances may also have more than one flavor, or none (i.e., a bland (淡) flavor). Each of the Five Flavors corresponds to one of the zàng organs, which in turn corresponds to one of the Five Phases: A flavor implies certain properties and presumed therapeutic "actions" of a substance: saltiness "drains downward and softens hard masses"; sweetness is "supplementing, harmonizing, and moistening"; pungent substances are thought to induce sweat and act on qi and blood; sourness tends to be astringent (涩; 澀) in nature; bitterness "drains heat, purges the bowels, and eliminates dampness".

Specific function

These categories mainly include:

- exterior-releasing or exterior-resolving

- heat-clearing

- downward-draining or precipitating

- wind-damp-dispelling

- dampness-transforming

- promoting the movement of water and percolating dampness or dampness-percolating

- interior-warming

- qi-regulating or qi-rectifying

- dispersing food accumulation or food-dispersing

- worm-expelling

- stopping bleeding or blood-stanching

- quickening the Blood and dispelling stasis or blood-quickening or Blood-moving.

- transforming phlegm, stopping coughing and calming wheezing or phlegm-transforming and cough- and panting-suppressing

- Spirit-quieting or Shen-calming.

- calming the Liver and expelling wind or Liver-calming and wind-extinguishing

- orifice-opening

- supplementing or tonifying: this includes qi-supplementing, blood-nourishing, yin-enriching, and yang-fortifying.

- astriction-promoting or securing and astringing

- vomiting-inducing

- substances for external application

Nomenclature

Many herbs earn their names from their unique physical appearance. Examples of such names include Niu Xi (Radix cyathulae seu achyranthis), "cow's knees," which has big joints that might look like cow knees; Bai Mu Er (Fructificatio tremellae fuciformis), white wood ear,' which is white and resembles an ear; Gou Ji (Rhizoma cibotii), 'dog spine,' which resembles the spine of a dog.

Color

Color is not only a valuable means of identifying herbs, but in many cases also provides information about the therapeutic attributes of the herb. For example, yellow herbs are referred to as huang (yellow) or jin (gold). Huang Bai (Cortex Phellodendri) means 'yellow fir," and Jin Yin Hua (Flos Lonicerae) has the label 'golden silver flower."

Smell and taste

Unique flavors define specific names for some substances. Gan means 'sweet,' so Gan Cao (Radix glycyrrhizae) is 'sweet herb," an adequate description for the licorice root. "Ku" means bitter, thus Ku Shen (Sophorae flavescentis) translates as 'bitter herb.'

Geographic location

The locations or provinces in which herbs are grown often figure into herb names. For example, Bei Sha Shen (Radix glehniae) is grown and harvested in northern China, whereas Nan Sha Shen (Radix adenophorae) originated in southern China. And the Chinese words for north and south are respectively bei and nan.

Chuan Bei Mu (Bulbus fritillariae cirrhosae) and Chuan Niu Xi (Radix cyathulae) are both found in Sichuan province, as the character "chuan" indicates in their names.

Function

Some herbs, like Fang Feng (Radix Saposhnikoviae), literally 'prevent wind," prevents or treats wind-related illnesses. Xu Duan (Radix Dipsaci), literally 'restore the broken,' effectively treats torn soft tissues and broken bones.

Country of origin

Many herbs indigenous to other countries have been incorporated into the Chinese materia medica. Xi Yang Shen (Radix panacis quinquefolii), imported from North American crops, translates as 'western ginseng," while Dong Yang Shen (Radix ginseng Japonica), grown in and imported from North Asian countries, is 'eastern ginseng.'

Toxicity

From the earliest records regarding the use of medicinals to today, the toxicity of certain substances has been described in all Chinese materia medica. Since TCM has become more popular in the Western world, there are increasing concerns about the potential toxicity of many traditional Chinese medicinals including plants, animal parts and minerals. For most medicinals, efficacy and toxicity testing are based on traditional knowledge rather than laboratory analysis. The toxicity in some cases could be confirmed by modern research (i.e., in scorpion); in some cases it could not (i.e., in Curculigo). Further, ingredients may have different names in different locales or in historical texts, and different preparations may have similar names for the same reason, which can create inconsistencies and confusion in the creation of medicinals, with the possible danger of poisoning. Edzard Ernst "concluded that adverse effects of herbal medicines are an important albeit neglected subject in dermatology, which deserves further systematic investigation." Research suggests that the toxic heavy metals and undeclared drugs found in Chinese herbal medicines might be a serious health issue.

Substances known to be potentially dangerous include aconite, secretions from the Asiatic toad, powdered centipede, the Chinese beetle (Mylabris phalerata, Ban mao), and certain fungi. There are health problems associated with Aristolochia. Toxic effects are also frequent with Aconitum. To avoid its toxic adverse effects Xanthium sibiricum must be processed. Hepatotoxicity has been reported with products containing Reynoutria multiflora (synonym Polygonum multiflorum), glycyrrhizin, Senecio and Symphytum. The evidence suggests that hepatotoxic herbs also include Dictamnus dasycarpus, Astragalus membranaceous, and Paeonia lactiflora; although there is no evidence that they cause liver damage. Contrary to popular belief, Ganoderma lucidum mushroom extract, as an adjuvant for cancer immunotherapy, appears to have the potential for toxicity.

Also, adulteration of some herbal medicine preparations with conventional drugs which may cause serious adverse effects, such as corticosteroids, phenylbutazone, phenytoin, and glibenclamide, has been reported.

However, many adverse reactions are due to misuse or abuse of Chinese medicine. For example, the misuse of the dietary supplement Ephedra (containing ephedrine) can lead to adverse events including gastrointestinal problems as well as sudden death from cardiomyopathy. Products adulterated with pharmaceuticals for weight loss or erectile dysfunction are one of the main concerns. Chinese herbal medicine has been a major cause of acute liver failure in China.

Most Chinese herbs are safe but some have shown not to be. Reports have shown products being contaminated with drugs, toxins, or false reporting of ingredients. Some herbs used in TCM may also react with drugs, have side effects, or be dangerous to people with certain medical conditions.

Efficacy

Only a few trials exist that are considered to have adequate methodology by scientific standards. Proof of effectiveness is poorly documented or absent. A 2016 Cochrane review found "insufficient evidence that Chinese Herbal Medicines were any more or less effective than placebo or Hormonal Therapy" for the relief of menopause related symptoms. A 2012 Cochrane review found no difference in decreased mortality for SARS patients when Chinese herbs were used alongside Western medicine versus Western medicine exclusively. A 2010 Cochrane review found there is not enough robust evidence to support the effectiveness of traditional Chinese medicine herbs to stop the bleeding from haemorrhoids. A 2008 Cochrane review found promising evidence for the use of Chinese herbal medicine in relieving painful menstruation, compared to conventional medicine such as NSAIDs and the oral contraceptive pill, but the findings are of low methodological quality. A 2012 Cochrane review found weak evidence suggesting that some Chinese medicinal herbs have a similar effect at preventing and treating influenza as antiviral medication. Due to the poor quality of these medical studies, there is insufficient evidence to support or dismiss the use of Chinese medicinal herbs for the treatment of influenza. There is a need for larger and higher quality randomized clinical trials to determine how effective Chinese herbal medicine is for treating people with influenza. A 2005 Cochrane review found that although the evidence was weak for the use of any single herb, there was low quality evidence that some Chinese medicinal herbs may be effective for the treatment of acute pancreatitis.

Successful results have been scarce: artemisinin is one of few examples. An effective treatment for malaria, it was derived from Artemisia annua which is traditionally used to treat fever. Chinese herbology is largely pseudoscience, with no valid mechanism of action for the majority of its treatments.

Ecological impacts

The traditional practice of using (by now) endangered species is controversial within TCM. Modern Materia Medicas such as Bensky, Clavey and Stoger's comprehensive Chinese herbal text discuss substances derived from endangered species in an appendix, emphasizing alternatives.

Parts of endangered species used as TCM drugs include tiger bones and rhinoceros horn. Poachers supply the black market with such substances, and the black market in rhinoceros horn, for example, has reduced the world's rhino population by more than 90 percent over the past 40 years. Concerns have also arisen over the use of turtle plastron and seahorses.

TCM recognizes bear bile as a medicinal. In 1988, the Chinese Ministry of Health started controlling bile production, which previously used bears killed before winter. Now bears are fitted with a sort of permanent catheter, which is more profitable than killing the bears. More than 12,000 asiatic black bears are held in "bear farms", where they suffer cruel conditions while being held in tiny cages. The catheter leads through a permanent hole in the abdomen directly to the gall bladder, which can cause severe pain. Increased international attention has mostly stopped the use of bile outside of China; gallbladders from butchered cattle (牛胆; 牛膽; niú dǎn) are recommended as a substitute for this ingredient.

Collecting American ginseng to assist the Asian traditional medicine trade has made ginseng the most harvested wild plant in North America for the last two centuries, which eventually led to a listing on CITES Appendix II.

Herbs in use

Chinese herbology is a pseudoscientific practice with potentially unreliable product quality, safety hazards or misleading health advice. There are regulatory bodies, such as China GMP (Good Manufacturing Process) of herbal products. However, there have been notable cases of an absence of quality control during herbal product preparation. There is a lack of high-quality scientific research on herbology practices and product effectiveness for anti-disease activity. In the herbal sources listed below, there is little or no evidence for efficacy or proof of safety across consumer age groups and disease conditions for which they are intended.

There are over 300 herbs in common use. Some of the most commonly used herbs are Ginseng (人参; 人參; rénshēn), wolfberry (枸杞子; gǒuqǐzǐ), dong quai (Angelica sinensis, 当归; 當歸; dāngguī), astragalus (黄耆; 黃耆; huángqí), atractylodes (白术; 白朮; báizhú), bupleurum (柴胡; cháihú), cinnamon (cinnamon twigs (桂枝; guìzhī) and cinnamon bark (肉桂; ròuguì)), coptis (黄连; 黃連; huánglián), ginger (姜; 薑; jiāng), hoelen (茯苓; fúlíng), licorice (甘草; gāncǎo), ephedra sinica (麻黄; 麻黃; máhuáng), peony (white: 白芍; báisháo and reddish: 赤芍; chìsháo), rehmannia (地黄; 地黃; dìhuáng), rhubarb (大黄; 大黃; dàhuáng), and salvia (丹参; 丹參; dānshēn).

50 fundamental herbs

In Chinese herbology, there are 50 "fundamental" herbs, as given in the reference text, although these herbs are not universally recognized as such in other texts. The herbs are:

| Binomial nomenclature | Chinese name | English common name (when available) |

|---|---|---|

| Agastache rugosa, Pogostemon cablin | huò xiāng (藿香) | Korean mint, Patchouli |

| Alangium chinense | bā jiǎo fēng (八角枫) | Chinese Alangium root |

| Anemone chinensis (syn. Pulsatilla chinensis) | bái tóu weng (白头翁) | Chinese anemone |

| Anisodus tanguticus | shān làng dàng (山莨菪) |

|

| Ardisia japonica | zǐ jīn niú (紫金牛) | Marlberry |

| Aster tataricus | zǐ wǎn (紫菀) | Tatar aster, Tartar aster |

| Astragalus propinquus (syn. Astragalus membranaceus) | huáng qí (黄芪) or běi qí (北芪) | Mongolian milkvetch |

| Camellia sinensis | chá shù (茶树) or chá yè (茶叶) | Tea plant |

| Cannabis sativa | dà má (大麻) | Cannabis |

| Carthamus tinctorius | hóng huā (红花) | Safflower |

| Cinnamomum cassia | ròu gùi (肉桂) | Cassia, Chinese cinnamon |

| Cissampelos pareira | xí shēng téng (锡生藤) or (亞乎奴) | Velvet leaf |

| Coptis chinensis | duǎn è huáng lián (短萼黄连) | Chinese goldthread |

| Corydalis yanhusuo | yán hú suǒ (延胡索) | Chinese poppy of Yan Hu Sou |

| Croton tiglium | bā dòu (巴豆) | Purging croton |

| Daphne genkwa | yuán huā (芫花) | Lilac daphne |

| Datura metel | yáng jīn huā (洋金花) | Devil's trumpet |

| Datura stramonium | zǐ huā màn tuó luó (紫花曼陀萝) | Jimson weed |

| Dendrobium nobile | shí hú (石斛) or shí hú lán (石斛兰) | Noble dendrobium |

| Dichroa febrifuga | cháng shān (常山) | Blue evergreen hydrangea, Chinese quinine |

| Ephedra sinica | cǎo má huáng (草麻黄) | Chinese ephedra |

| Eucommia ulmoides | dù zhòng (杜仲) | Hardy rubber tree |

| Euphorbia pekinensis | dà jǐ (大戟) | Peking spurge |

| Flueggea suffruticosa (formerly Securinega suffruticosa) | yī yè qiū (一叶秋) |

|

| Forsythia suspensa | liánqiáo[83] (连翘) | Weeping forsythia |

| Gentiana loureiroi | dì dīng (地丁) |

|

| Gleditsia sinensis | zào jiá (皂荚) | Chinese honeylocust |

| Glycyrrhiza uralensis | gān cǎo (甘草) | Licorice |

| Hydnocarpus anthelminticus (syn. H. anthelminthica) | dà fēng zǐ (大风子) | Chaulmoogra tree |

| Ilex purpurea | dōngqīng (冬青) | Purple holly |

| Leonurus japonicus | yì mǔ cǎo (益母草) | Chinese motherwort |

| Ligusticum wallichii | chuān xiōng (川芎) | Szechwan lovage |

| Lobelia chinensis | bàn biān lián (半边莲) | Creeping lobelia |

| Phellodendron amurense | huáng bǎi (黄柏) | Amur cork tree |

| Platycladus orientalis (formerly Thuja orientalis) | cè bǎi (侧柏) | Chinese arborvitae |

| Pseudolarix amabilis | jīn qián sōng (金钱松) | Golden larch |

| Psilopeganum sinense | shān má huáng (山麻黄) | Naked rue |

| Pueraria lobata | gé gēn (葛根) | Kudzu |

| Rauvolfia serpentina | shégēnmù (蛇根木), cóng shégēnmù (從蛇根木) or yìndù shé mù (印度蛇木) | Sarpagandha, Indian snakeroot |

| Rehmannia glutinosa | dìhuáng (地黄) | Chinese foxglove |

| Rheum officinale | yào yòng dà huáng (药用大黄) | Chinese or Eastern rhubarb |

| Rhododendron qinghaiense | Qīng hǎi dù juān (青海杜鹃) |

|

| Saussurea costus | yún mù xiāng (云木香) | Costus root |

| Schisandra chinensis | wǔ wèi zi (五味子) | Chinese magnolia vine |

| Scutellaria baicalensis | huáng qín (黄芩) | Baikal skullcap |

| Stemona tuberosa | bǎi bù (百部) |

|

| Stephania tetrandra | fáng jǐ (防己) | Stephania root |

| Styphnolobium japonicum (formerly Sophora japonica) | huái (槐), huái shù (槐树), or huái huā (槐花) | Pagoda tree |

| Trichosanthes kirilowii | guā lóu (栝楼) | Chinese cucumber |

| Wikstroemia indica | liāo gē wáng (了哥王) | Indian stringbush |

Other Chinese herbs

In addition to the above, many other Chinese herbs and other substances are in common use, and these include:

- Akebia quinata (木通)

- Arisaema heterophyllum[87][88] (胆南星)

- Chenpi (sun-dried tangerine (mandarin) peel) (陳皮)

- Clematis (威灵仙)

- Concretio silicea bambusae (天竺黄)

- Cordyceps sinensis (冬虫夏草)

- Curcuma (郁金)

- Dalbergia odorifera (降香)

- Myrrh (没药)

- Frankincense (乳香)

- Persicaria (桃仁)

- Patchouli' (广藿香)

- Polygonum (虎杖)

- Sparganium (三棱)

- Zedoary (Curcuma zedoaria) (莪朮)