The Ancestral Puebloans, also known as the Anasazi, were an ancient Native American culture that spanned the present-day Four Corners region of the United States, comprising southeastern Utah, northeastern Arizona, northwestern New Mexico, and southwestern Colorado. They are believed to have developed, at least in part, from the Oshara Tradition, which developed from the Picosa culture. The people and their archaeological culture are often referred to as Anasazi, meaning "ancient enemies", as they were called by Navajo. Contemporary Puebloans object to the use of this term, with some viewing it as derogatory.

The Ancestral Puebloans lived in a range of structures that included small family pit houses, larger structures to house clans, grand pueblos, and cliff-sited dwellings for defense. They had a complex network linking hundreds of communities and population centers across the Colorado Plateau. They held a distinct knowledge of celestial sciences that found form in their architecture. The kiva, a congregational space that was used mostly for ceremonies, was an integral part of community structure.

Archaeologists continue to debate when this distinct culture emerged. The current agreement, based on terminology defined by the Pecos Classification, suggests their emergence around the 12th century BC, during the archaeologically designated Early Basketmaker II Era. Beginning with the earliest explorations and excavations, researchers identified Ancestral Puebloans as the forerunners of contemporary Pueblo peoples. Three UNESCO World Heritage Sites located in the United States are credited to the Pueblos: Mesa Verde National Park, Chaco Culture National Historical Park and Taos Pueblo.

Etymology

Pueblo, which means "village" in Spanish, was a term originating with the Spanish explorers who used it to refer to the people's particular style of dwelling. The Navajo people, who now reside in parts of former Pueblo territory, referred to the ancient people as Anaasází, an exonym meaning "ancestors of our enemies", referring to their competition with the Pueblo peoples. The Navajo now use the term in the sense of referring to "ancient people" or "ancient ones".

Hopi people use the term Hisatsinom, meaning "ancient people", to describe the Ancestral Puebloans.

Geography

The Ancestral Puebloans were one of four major prehistoric archaeological traditions recognized in the American Southwest. This area is sometimes referred to as Oasisamerica in the region defining pre-Columbian southwestern North America. The others are the Mogollon, Hohokam, and Patayan. In relation to neighboring cultures, the Ancestral Puebloans occupied the northeast quadrant of the area. The Ancestral Puebloan homeland centers on the Colorado Plateau, but extends from central New Mexico on the east to southern Nevada on the west.

Areas of southern Nevada, Utah, and Colorado form a loose northern boundary, while the southern edge is defined by the Colorado and Little Colorado Rivers in Arizona and the Rio Puerco and Rio Grande in New Mexico. Structures and other evidence of Ancestral Puebloan culture have been found extending east onto the American Great Plains, in areas near the Cimarron and Pecos Rivers and in the Galisteo Basin.

Terrain and resources within this large region vary greatly. The plateau regions have high elevations ranging from 4,500 to 8,500 feet (1,400 to 2,600 m). Extensive horizontal mesas are capped by sedimentary formations and support woodlands of junipers, pinon, and ponderosa pines, each favoring different elevations. Wind and water erosion have created steep-walled canyons, and sculpted windows and bridges out of the sandstone landscape. In areas where resistant strata (sedimentary rock layers), such as sandstone or limestone, overlie more easily eroded strata such as shale, rock overhangs formed. The Ancestral Puebloans favored building under such overhangs for shelters and defensive building sites.

All areas of the Ancestral Puebloan homeland suffered from periods of drought, and wind and water erosion. Summer rains could be unreliable and often arrived as destructive thunderstorms. While the amount of winter snowfall varied greatly, the Ancestral Puebloans depended on the snow for most of their water. Snow melt allowed the germination of seeds, both wild and cultivated, in the spring.

Where sandstone layers overlay shale, snow melt could accumulate and create seeps and springs, which the Ancestral Puebloans used as water sources. Snow also fed the smaller, more predictable tributaries, such as the Chinle, Animas, Jemez, and Taos Rivers. The larger rivers were less directly important to the ancient culture, as smaller streams were more easily diverted or controlled for irrigation.

Cultural characteristics

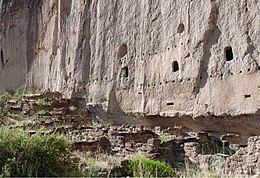

The Ancestral Puebloan culture is perhaps best known for the stone and earth dwellings its people built along cliff walls, particularly during the Pueblo II and Pueblo III eras, from about 900 to 1350 AD in total. The best-preserved examples of the stone dwellings are now protected within United States' national parks, such as Navajo National Monument, Chaco Culture National Historical Park, Mesa Verde National Park, Canyons of the Ancients National Monument, Aztec Ruins National Monument, Bandelier National Monument, Hovenweep National Monument, and Canyon de Chelly National Monument.

These villages, called pueblos by Spanish colonists, were accessible only by rope or through rock climbing. These astonishing building achievements had modest beginnings. The first Ancestral Puebloan homes and villages were based on the pit-house, a common feature in the Basketmaker periods.

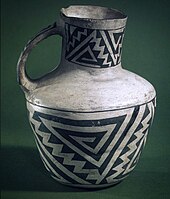

Ancestral Puebloans are also known for their pottery. In general, pottery used for cooking or storage in the region was unpainted gray, either smooth or textured. Pottery used for more formal purposes was often more richly adorned. In the northern or "Anasazi" portion of the Ancestral Pueblo world, from about 500 to 1300 AD, the most common decorated pottery had black-painted designs on white or light gray backgrounds. Decoration is characterized by fine hatching, and contrasting colors are produced by the use of mineral-based paint on a chalky background. South of the Anasazi territory, in Mogollon settlements, pottery was more often hand-coiled, scraped, and polished, with red to brown coloring.

Some tall cylinders are considered ceremonial vessels, while narrow-necked jars may have been used for liquids. Ware in the southern portion of the region, particularly after 1150 AD, is characterized by heavier black-line decoration and the use of carbon-based colorants. In northern New Mexico, the local "black on white" tradition, the Rio Grande white wares, continued well after 1300 AD.

Changes in pottery composition, structure, and decoration are signals of social change in the archaeological record. This is particularly true as the peoples of the American Southwest began to leave their traditional homes and migrate south. According to archaeologists Patricia Crown and Steadman Upham, the appearance of the bright colors on Salado Polychromes in the 14th century may reflect religious or political alliances on a regional level. Late 14th- and 15th-century pottery from central Arizona, widely traded in the region, has colors and designs which may derive from earlier ware by both Ancestral Pueblo and Mogollon peoples.

The Ancestral Puebloans also created many petroglyphs and pictographs. The pictograph style with which they are associated is the called the Barrier Canyon Style. This form of pictograph is painted in areas in which the images would be protected from the sun yet visible to a group of people. The figures are sometimes phantom or alien looking. The Holy Ghost panel in the Horseshoe Canyon is considered to be one of the earliest uses of graphical perspective where the largest figure appears to take on a three dimensional representation.

Recent archaeological evidence has established that in at least one great house, Pueblo Bonito, the elite family whose burials associate them with the site practiced matrilineal succession. Room 33 in Pueblo Bonito, the richest burial ever excavated in the Southwest, served as a crypt for one powerful lineage, traced through the female line, for approximately 330 years. While other Ancestral Pueblo burials have not yet been subjected to the same archaeogenomic testing, the survival of matrilineal descent among contemporary Puebloans suggests that this may have been a widespread practice among Ancestral Puebloans.

Architecture

The Ancestral Pueblo people in the North American Southwest crafted a unique architecture with planned community spaces. Population centers such as Chaco Canyon (outside Crownpoint, New Mexico), Mesa Verde (near Cortez, Colorado), and Bandelier National Monument (near Los Alamos, New Mexico) have brought renown to the Ancestral Pueblo peoples. They consisted of apartment complexes and structures made of stone, adobe mud, and other local material, or were carved into canyon walls. Developed within these cultures, the people also adopted design details from other cultures as far away as contemporary Mexico.

These buildings were usually multistoried and multipurposed, and surrounded open plazas and viewsheds. They were occupied by hundreds to thousands of people. These complexes hosted cultural and civic events and infrastructure that supported a vast outlying region hundreds of miles away linked by transportation roadways.

Built well before 1492 AD, these towns and villages were located in defensive positions, for example on high, steep mesas such as at Mesa Verde or present-day Acoma Pueblo, called the "Sky City", in New Mexico. Before 900 AD and progressing past the 13th century, the population complexes were major culture centers. In Chaco Canyon, Chacoan developers quarried sandstone blocks and hauled timber from great distances, assembling 15 major complexes. These ranked as the largest buildings in North America until the late 19th century.

Evidence of archaeoastronomy at Chaco has been proposed, with the Sun Dagger petroglyph at Fajada Butte a popular example. Many Chacoan buildings may have been aligned to capture the solar and lunar cycles, requiring generations of astronomical observations and centuries of skillfully coordinated construction. The Chacoans abandoned the canyon, probably due to climate change beginning with a 50-year drought starting in 1130.

Great Houses

| Ancestral Puebloan Periods |

|---|

|

|

Archaic–Early Basketmaker Era 7000 – 1500 BCE |

|

Early Basketmaker II Era 1500 BCE – 50 CE |

|

Late Basketmaker II Era 50 – 500 |

|

Basketmaker III Era 500 – 750 |

|

Pueblo I Period 750 – 900 |

|

Pueblo II Period 900 – 1150 |

|

Pueblo III Period 1150 – 1350 |

|

Pueblo IV Period 1350 – 1600 |

|

Pueblo V Period 1600 – present |

Immense complexes known as "great houses" embodied worship at Chaco. Archaeologists have found musical instruments, jewelry, ceramics, and ceremonial items, indicating people in Great Houses were elite, wealthier families. They hosted indoor burials, where gifts were interred with the dead, often including bowls of food and turquoise beads.

Over centuries, architectural forms evolved but the complexes kept some core traits, such as their size. They averaged more than 200 rooms each, and some had 700 rooms. Rooms were very large, with higher ceilings than Ancestral Pueblo buildings of earlier periods. They were well-planned: vast sections were built in a single stage.

Most houses faced south. Plazas were almost always surrounded by buildings of sealed-off rooms or high walls. There were often four or five stories, with single-story rooms facing the plaza; room blocks were terraced to allow the tallest sections to compose the pueblo's rear edifice. Rooms were often organized into suites, with front rooms larger than rear, interior, and storage rooms or areas.

Ceremonial structures known as kivas were built in proportion to the number of rooms in a pueblo. A small kiva was built for roughly every 29 rooms. Nine complexes each had a Great Kiva, up to 63 feet (19 m) in diameter. T-shaped doorways and stone lintels marked all Chacoan kivas.

Although simple and compound walls were often used, great houses usually had core-and-veneer walls: rubble filled the gap between parallel load-bearing walls of dressed, flat sandstone blocks bound in clay mortar. Walls were covered in a veneer of small sandstone pieces, which were pressed into a layer of binding mud. These surfacing stones were often arranged in distinctive patterns.

The Chacoan structures together required the wood of 200,000 conifer trees, mostly hauled – on foot – from mountain ranges up to 70 miles (110 km) away.

Ceremonial infrastructure

One of the most notable aspects of Ancestral Puebloan infrastructure is the Chaco Road at Chaco Canyon, a system of roads radiating from many great house sites such as Pueblo Bonito, Chetro Ketl, and Una Vida. They led toward small outlier sites and natural features in the canyon and outside.

Through satellite images and ground investigations, archaeologists have found eight main roads that together run for more than 180 miles (300 km), and are more than 30 feet (10 m) wide. These were built by excavating into a smooth, leveled surface in the bedrock or removing vegetation and soil. Large ramps and stairways in the cliff rock connect the roads above the canyon to sites at the bottom.

The largest roads, built at the same time as many of the great houses (1000 to 1125 AD), are: the Great North Road, the South Road, the Coyote Canyon Road, the Chacra Face Road, Ahshislepah Road, Mexican Springs Road, the West Road, and the shorter Pintado-Chaco Road. Simple structures like berms and walls are sometimes aligned along the roads. Some tracts of the roads lead to natural features such as springs, lakes, mountain tops, and pinnacles.

Great North Road

The longest and best-known of these roads is the Great North Road, which originates from different routes close to Pueblo Bonito and Chetro Ketl. These roads converge at Pueblo Alto and from there lead north beyond the canyon limits. Along the road there are only small, isolated structures.[citation needed]

Archaeological interpretations of the Chaco road system are divided between an economic purpose and a symbolic, ideological or religious role.

The system was discovered in the late 19th century and excavated in the 1970s. By the late 20th century, aerial and satellite photographs helped in the study. Archaeologists suggested that the road's main purpose was to transport local and exotic goods to and from the canyon. The economic purpose of the Chaco road system is shown by the presence of luxury items at Pueblo Bonito and elsewhere in the canyon. Items such as macaws, turquoise and seashells, which are not part of this environment, and imported vessels distinguished by design, prove that the Chaco traded with distant regions. The widespread use of timber in Chacoan constructions required a large system of easy transportation, as timber was not locally available. Analysis of strontium isotopes shows that much of the timber came from distant mountain ranges.

Cliff communities

Throughout the southwest Ancestral Puebloan region are building complexes in shallow caves and under rock overhangs in canyon walls. Unlike earlier structures and villages atop mesas this was a regional 13th-century trend of gathering the growing populations into close, defensible quarters. There were buildings for housing, defense, and storage. These were built mostly of blocks of hard sandstone, held together and plastered with adobe mortar. Constructions had many similarities, but unique forms due to the unique rock topography.

The best-known site is at Mesa Verde, with a large number of well-preserved cliff dwellings. This area included common Pueblo architectural forms, such as kivas, towers, and pit-houses, but the space restrictions of these alcoves resulted in far denser populations. Mug House, a typical cliff dwelling of the period, was home to around 100 people who shared 94 small rooms and eight kivas, built right up against each other and sharing many walls. Builders maximized space use and no area was off-limits.

Not all the people in the region lived in cliff dwellings; many colonized the canyon rims and slopes in multifamily structures that grew to unprecedented size as populations swelled. Decorative motifs for these sandstone/mortar structures, both cliff dwellings and not, included T-shaped windows and doors. This has been taken by some archaeologists, such as Stephen Lekson (1999), as evidence of the continuation of the Chaco Canyon elite system, which had seemingly collapsed a century earlier. Other researchers instead explain these motifs as part a wider Puebloan style or religion.

History

Origins

During the period from 700 to 1130 AD (Pueblo I and II Eras), the population grew fast due to consistent and regular rainfall which supported agriculture. Studies of skeletal remains show increased fertility rather than decreased mortality. However, this tenfold population increase over a few generations was probably also due to migrations of people from surrounding areas. Innovations such as pottery, food storage, and agriculture enabled this rapid growth. Over several decades, the Ancestral Puebloan culture spread across the landscape.

Ancestral Puebloan culture has been divided into three main areas or branches, based on geographical location:

- Chaco Canyon (northwest New Mexico)

- Kayenta (northeast Arizona), and

- Northern San Juan (Mesa Verde and Hovenweep National Monument) (southwest Colorado and southeastern Utah)

Modern Pueblo oral traditions hold that the Ancestral Puebloans originated from sipapu, where they emerged from the underworld. For unknown ages, they were led by chiefs and guided by spirits as they completed vast migrations throughout the continent of North America. They settled first in the Ancestral Puebloan areas for a few hundred years before moving to their present locations.

Migration from the homeland

The Ancestral Puebloans left their established homes in the 12th and 13th centuries. The main reason is unclear. Factors discussed include global or regional climate change, prolonged drought, environmental degradation such as cyclical periods of topsoil erosion deforestation, hostility from new arrivals, religious or cultural change, and influence from Mesoamerican cultures. Many of these possibilities are supported by archaeological evidence.

Current scholarly consensus is that Ancestral Puebloans responded to pressure from Numic-speaking peoples moving onto the Colorado Plateau, as well as climate change that resulted in agricultural failures. The archaeological record indicates that for Ancestral Puebloans to adapt to climatic change by changing residences and locations was not unusual. Early Pueblo I Era sites may have housed up to 600 individuals in a few separate but closely spaced settlement clusters. However, they were generally occupied for 30 years or less. Archaeologist Timothy A. Kohler excavated large Pueblo I sites near Dolores, Colorado, and discovered that they were established during periods of above-average rainfall. This allowed crops to be grown without requiring irrigation. At the same time, nearby areas that suffered significantly drier patterns were abandoned.

Ancestral Puebloans attained a cultural "Golden Age" between about 900 and 1150. During this time, generally classed as Pueblo II Era, the climate was relatively warm and rainfall mostly adequate. Communities grew larger and were inhabited for longer. Highly specific local traditions in architecture and pottery emerged, and trade over long distances appears to have been common. Domesticated turkeys appeared.

After around 1130, North America had significant climatic change in the form of a 300-year drought called the Great Drought. This also led to the collapse of the Tiwanaku civilization around Lake Titicaca in present-day Bolivia. The contemporary Mississippian culture also collapsed during this period. Confirming evidence dated between 1150 and 1350 has been found in excavations of the western regions of the Mississippi Valley, which show long-lasting patterns of warmer, wetter winters and cooler, drier summers.

In this later period, the Pueblo II became more self-contained, decreasing trade and interaction with more distant communities. Southwest farmers developed irrigation techniques appropriate to seasonal rainfall, including soil and water control features such as check dams and terraces. The population of the region continued to be mobile, abandoning settlements and fields under adverse conditions. There was also a drop in water table was due to a different cycle unrelated to rainfall. This forced the abandonment of settlements in the more arid or overfarmed locations.

Evidence suggests a profound change in religion in this period. Chacoan and other structures constructed originally along astronomical alignments, and thought to have served important ceremonial purposes to the culture, were systematically dismantled. Doorways were sealed with rock and mortar. Kiva walls show marks from great fires set within them, which probably required removal of the massive roof – a task which would require significant effort. Habitations were abandoned, and tribes divided and resettled far.

This evidence suggests that the religious structures were abandoned deliberately over time. Puebloan tradition holds that the ancestors had achieved great spiritual power and control over natural forces. They used their power in ways that caused nature to change, and caused changes that were never meant to occur. Possibly, the dismantling of their religious structures was an effort to symbolically undo the changes they believed they caused due to their abuse of their spiritual power, and thus make amends with nature.

Most modern Pueblo peoples (whether Keresans, Hopi, or Tanoans) assert the Ancestral Puebloans did not "vanish", as is commonly portrayed. They say that the people migrated to areas in the southwest with more favorable rainfall and dependable streams. They merged into the various Pueblo peoples whose descendants still live in Arizona and New Mexico. This perspective was also presented by early 20th-century anthropologists, including Frank Hamilton Cushing, J. Walter Fewkes, and Alfred V. Kidder.

Many modern Pueblo tribes trace their lineage from specific settlements. For example, the San Ildefonso Pueblo people believe that their ancestors lived in both the Mesa Verde and the Bandelier areas. Evidence also suggests that a profound change took place in the Ancestral Pueblo area and areas inhabited by their cultural neighbors, the Mogollon. Historian James W. Loewen agrees with this oral tradition in his book, Lies Across America: What Our Historic Markers and Monuments Get Wrong (1999). No academic consensus exists with the professional archeological and anthropological community on this issue.

Warfare

Environmental stress may have caused changes in social structure, leading to conflict and warfare. Near Kayenta, Arizona, Jonathan Haas of the Field Museum in Chicago has been studying a group of Ancestral Puebloan villages that relocated from the canyons to the high mesa tops during the late 13th century. Haas believes that the reason to move so far from water and arable land was a defense against enemies. He asserts that isolated communities relied on raiding for food and supplies, and that internal conflict and warfare became common in the 13th century.

This conflict may have been aggravated by the influx of less settled peoples, Numic-speakers such as the Utes, Shoshones, and Paiute people, who may have originated in what is today California, and the arrival of the Athabaskan-speaking Diné who migrated from the north during this time and subsequently became the Navajo and Apache tribes most notably. Others suggest that more developed villages, such as that at Chaco Canyon, exhausted their environments, resulting in widespread deforestation and eventually the fall of their civilization through warfare over depleted resources.

A 1997 excavation at Cowboy Wash near Dolores, Colorado found remains of at least 24 human skeletons that showed evidence of violence and dismemberment, with strong indications of cannibalism. This modest community appears to have been abandoned during the same time period. Other excavations within the Ancestral Puebloan cultural area have produced varying numbers of unburied, and in some cases dismembered, bodies. In a 2010 paper, Potter and Chuipka argued that evidence at Sacred Ridge site, near Durango, Colorado, is best interpreted as warfare related to competition and ethnic cleansing.

This evidence of warfare, conflict, and cannibalism is hotly debated by some scholars and interest groups. Suggested alternatives include: a community suffering the pressure of starvation or extreme social stress, dismemberment and cannibalism as religious ritual or in response to religious conflict, the influx of outsiders seeking to drive out a settled agricultural community via calculated atrocity, or an invasion of a settled region by nomadic raiders who practiced cannibalism.

Anasazi as a cultural label

The term "Anasazi" was established in archaeological terminology through the Pecos Classification system in 1927. It had been adopted from the Navajo. Archaeologist Linda Cordell discussed the word's etymology and use:

The name "Anasazi" has come to mean "ancient people," although the word itself is Navajo, meaning "enemy ancestors." [The Navajo word is anaasází (<anaa- "enemy", sází "ancestor").] The term was first applied to ruins of the Mesa Verde by Richard Wetherill, a rancher and trader who, in 1888–1889, was the first Anglo-American to explore the sites in that area. Wetherill knew and worked with Navajos and understood what the word meant. The name was further sanctioned in archaeology when it was adopted by Alfred V. Kidder, the acknowledged dean of Southwestern Archaeology. Kidder felt that it was less cumbersome than a more technical term he might have used. Subsequently some archaeologists who would try to change the term have worried that because the Pueblos speak different languages, there are different words for "ancestor," and using one might be offensive to people speaking other languages.

Many contemporary Pueblo peoples object to the use of the term Anasazi; controversy exists among them on a native alternative. Some modern descendants of this culture often choose to use the term "Ancestral Pueblo" peoples. Contemporary Hopi use the word Hisatsinom in preference to Anasazi.

Cultural distinctions

Archaeological cultural units such as Ancestral Puebloan, Hohokam, Patayan, or Mogollon are used by archaeologists to define material culture similarities and differences that may identify prehistoric sociocultural units, equivalent to modern societies or peoples. The names and divisions are classification devices based on theoretical perspectives, analytical methods, and data available at the time of analysis and publication. They are subject to change, not only on the basis of new information and discoveries, but also as attitudes and perspectives change within the scientific community. It should not be assumed that an archaeological division or culture unit corresponds to a particular language group or to a socio-political entity such as a tribe.

Current terms and conventions have significant limitations:

- Archaeological research focuses on items left behind during people's activities: fragments of pottery vessels, garbage, human remains, stone tools or evidence left from the construction of dwellings. However, many other aspects of the culture of prehistoric peoples are not tangible. Their beliefs and behavior are difficult to decipher from physical materials, and their languages remain unknown as they had no known writing system.

- Cultural divisions are tools of the modern scientist, and so should not be considered similar to divisions or relationships which the ancient residents may have recognized. Modern cultures in this region, many of whom claim some of these ancient people as ancestors, express a striking range of diversity in lifestyles, social organization, language and religious beliefs. This suggests the ancient people were also more diverse than their material remains may suggest.

- The modern term "style" has a bearing on how material items such as pottery or architecture can be interpreted. Within a people, different means to accomplish the same goal can be adopted by subsets of the larger group. For example, in modern Western cultures, there are alternative styles of clothing that characterize older and younger generations. Some cultural differences may be based on linear traditions, on teaching from one generation or "school" to another. Other varieties in style may have distinguished between arbitrary groups within a culture, perhaps defining status, gender, clan or guild affiliation, religious belief or cultural alliances. Variations may also simply reflect the different resources available in a given time or area.

Defining cultural groups, such as the Ancestral Puebloans, tends to create an image of territories separated by clear-cut boundaries, like border boundaries separating modern states. These did not exist. Prehistoric people traded, worshipped, collaborated, and fought most often with other nearby groups. Cultural differences should therefore be understood as clinal: "increasing gradually as the distance separating groups also increases".

Departures from the expected pattern may occur because of unidentified social or political situations or because of geographic barriers. In the Southwest, mountain ranges, rivers, and most obviously, the Grand Canyon, can be significant barriers for human communities, likely reducing the frequency of contact with other groups. Current opinion holds that the closer cultural similarity between the Mogollon and Ancestral Puebloans, and their greater differences from the Hohokam and Patayan, is due to both the geography and the variety of climate zones in the Southwest.