Color television is a television transmission technology that includes information on the color of the picture, so the video image can be displayed in color on the television set. It is considered an improvement on the earliest television technology, monochrome or black-and-white television, in which the image is displayed in shades of gray (grayscale). Television broadcasting stations and networks in most parts of the world upgraded from black-and-white to color transmission between the 1960s and the 1980s. The invention of color television standards is an important part of the history of television, and it is described in the technology of television article.

Transmission of color images using mechanical scanners had been conceived as early as the 1880s. A practical demonstration of mechanically scanned color television was given by John Logie Baird in 1928, but the limitations of a mechanical system were apparent even then. Development of electronic scanning and display made an all-electronic system possible. Early monochrome transmission standards were developed prior to World War II, but civilian electronics developments were frozen during much of the war. In August 1944, Baird gave the world's first demonstration of a practical fully electronic color television display. In the United States, commercially competing color standards were developed, finally resulting in the NTSC standard for color that retained compatibility with the prior monochrome system. Although the NTSC color standard was proclaimed in 1953 and limited programming became available, it was not until the early 1970s that color television in North America outsold black-and-white or monochrome units. Color broadcasting in Europe was not standardized on the PAL and SECAM formats until the 1960s.

Broadcasters began to switch from analog color television technology to digital television c. 2006; the exact year varies by country. This changeover is now complete in many countries, but analog television is still the standard elsewhere.

Development

The human eye's detection system in the retina consists primarily of two types of light detectors: rod cells that capture light, dark, and shapes/figures, and the cone cells that detect color. A typical retina contains 120 million rods and 4.5 million to 6 million cones, which are divided into three types, each one with a characteristic profile of excitability by different wavelengths of the spectrum of visible light. This means that the eye has far more resolution in brightness, or "luminance", than in color. However, post-processing of the optic nerve and other portions of the human visual system combine the information from the rods and cones to re-create what appears to be a high-resolution color image.

The eye has limited bandwidth to the rest of the visual system, estimated at just under 8 Mbit/s.[1] This manifests itself in a number of ways, but the most important in terms of producing moving images is the way that a series of still images displayed in quick succession will appear to be continuous smooth motion. This illusion starts to work at about 16 frame/s, and common motion pictures use 24 frame/s. Television, using power from the electrical grid, historically tuned its rate in order to avoid interference with the alternating current being supplied – in North America, some Central and South American countries, Taiwan, Korea, part of Japan, the Philippines, and a few other countries, this was 60 video fields per second to match the 60 Hz power, while in most other countries it was 50 fields per second to match the 50 Hz power. The NTSC color system changed from the black-and-white 60-fields-per-second standard to 59.94 fields per second to make the color circuitry simpler; the 1950s TV sets had matured enough that the power frequency/field rate mismatch was no longer important. Modern TV sets can display multiple field rates (50, 59.94, or 60, in either interlaced or progressive scan) while accepting power at various frequencies (often the operating range is specified as 48–62 Hz).

In its most basic form, a color broadcast can be created by broadcasting three monochrome images, one each in the three colors of red, green, and blue (RGB). When displayed together or in rapid succession, these images will blend together to produce a full-color image as seen by the viewer. To do so without making the images flicker, the refresh time of all three images put together would have to be above the critical limit, and generally the same as a single black and white image. This would require three times the number of images to be sent in the same time, and thus greatly increase the amount of radio bandwidth required to send the complete signal and thus similarly increase the required radio spectrum. Early plans for color television in the United States included a move from very high frequency (VHF) to ultra high frequency (UHF) to open up additional spectrum.

One of the great technical challenges of introducing color broadcast television was the desire to conserve bandwidth. In the United States, after considerable research, the National Television Systems Committee approved an all-electronic system developed by RCA that encoded the color information separately from the brightness information and greatly reduced the resolution of the color information in order to conserve bandwidth. The brightness image remained compatible with existing black-and-white television sets at slightly reduced resolution, while color-capable televisions could decode the extra information in the signal and produce a limited-resolution color display. The higher resolution black-and-white and lower resolution color images combine in the eye to produce a seemingly high-resolution color image. The NTSC standard represented a major technical achievement.

Early television

Experiments with facsimile image transmission systems that used radio broadcasts to transmit images date to the 19th century. It was not until the 20th century that advances in electronics and light detectors made what we know as television practical. A key problem was the need to convert a 2D image into a "1D" radio signal; some form of image scanning was needed to make this work. Early systems generally used a device known as a "Nipkow disk", which was a spinning disk with a series of holes punched in it that caused a spot to scan across and down the image. A single photodetector behind the disk captured the image brightness at any given spot, which was converted into a radio signal and broadcast. A similar disk was used at the receiver side, with a light source behind the disk instead of a detector.

A number of such mechanical television systems were being used experimentally in the 1920s. The best-known was John Logie Baird's, which was actually used for regular public broadcasting in Britain for several years. Indeed, Baird's system was demonstrated to members of the Royal Institution in London in 1926 in what is generally recognized as the first demonstration of a true, working television system. In spite of these early successes, all mechanical television systems shared a number of serious problems. Being mechanically driven, perfect synchronization of the sending and receiving discs was not easy to ensure, and irregularities could result in major image distortion. Another problem was that the image was scanned within a small, roughly rectangular area of the disk's surface, so that larger, higher-resolution displays required increasingly unwieldy disks and smaller holes that produced increasingly dim images. Rotating drums bearing small mirrors set at progressively greater angles proved more practical than Nipkow discs for high-resolution mechanical scanning, allowing images of 240 lines and more to be produced, but such delicate, high-precision optical components were not commercially practical for home receivers.

It was clear to a number of developers that a completely electronic scanning system would be superior, and that the scanning could be achieved in a vacuum tube via electrostatic or magnetic means. Converting this concept into a usable system took years of development and several independent advances. The two key advances were Philo Farnsworth's electronic scanning system, and Vladimir Zworykin's Iconoscope camera. The Iconoscope, based on Kálmán Tihanyi's early patents, superseded the Farnsworth-system. With these systems, the BBC began regularly scheduled black-and-white television broadcasts in 1936, but these were shut down again with the start of World War II in 1939. In this time thousands of television sets had been sold. The receivers developed for this program, notably those from Pye Ltd., played a key role in the development of radar.

By 22 March 1935, 180-line black-and-white television programs were being broadcast from the Paul Nipkow TV station in Berlin. In 1936, under the guidance of the Minister of Public Enlightenment and Propaganda, Joseph Goebbels, direct transmissions from fifteen mobile units at the Olympic Games in Berlin were transmitted to selected small television houses (Fernsehstuben) in Berlin and Hamburg.

In 1941, the first NTSC meetings produced a single standard for US broadcasts. US television broadcasts began in earnest in the immediate post-war era, and by 1950 there were 6 million televisions in the United States.

All-mechanical color

The basic idea of using three monochrome images to produce a color image had been experimented with almost as soon as black-and-white televisions had first been built.

Among the earliest published proposals for television was one by Maurice Le Blanc in 1880 for a color system, including the first mentions in television literature of line and frame scanning, although he gave no practical details. Polish inventor Jan Szczepanik patented a color television system in 1897, using a selenium photoelectric cell at the transmitter and an electromagnet controlling an oscillating mirror and a moving prism at the receiver. But his system contained no means of analyzing the spectrum of colors at the transmitting end, and could not have worked as he described it. An Armenian inventor, Hovannes Adamian, also experimented with color television as early as 1907. The first color television project is claimed by him, and was patented in Germany on March 31, 1908, patent number 197183, then in Britain, on April 1, 1908, patent number 7219, in France (patent number 390326) and in Russia in 1910 (patent number 17912).

Shortly after his practical demonstration of black and white television, on July 3, 1928, Baird demonstrated the world's first color transmission. This used scanning discs at the transmitting and receiving ends with three spirals of apertures, each spiral with filters of a different primary color; and three light sources, controlled by the signal, at the receiving end, with a commutator to alternate their illumination. The demonstration was of a young girl wearing different colored hats. The girl, Noele Gordon, later became a TV actress in the soap opera Crossroads. Baird also made the world's first color over-the-air broadcast on February 4, 1938, sending a mechanically scanned 120-line image from Baird's Crystal Palace studios to a projection screen at London's Dominion Theatre.

Mechanically scanned color television was also demonstrated by Bell Laboratories in June 1929 using three complete systems of photoelectric cells, amplifiers, glow-tubes, and color filters, with a series of mirrors to superimpose the red, green, and blue images into one full-color image.

Hybrid systems

As was the case with black-and-white television, an electronic means of scanning would be superior to the mechanical systems like Baird's. The obvious solution on the broadcast end would be to use three conventional Iconoscopes with colored filters in front of them to produce an RGB signal. Using three separate tubes each looking at the same scene would produce slight differences in parallax between the frames, so in practice a single lens was used with a mirror or prism system to separate the colors for the separate tubes. Each tube captured a complete frame and the signal was converted into radio in a fashion essentially identical to the existing black-and-white systems.

The problem with this approach was there was no simple way to recombine them on the receiver end. If each image was sent at the same time on different frequencies, the images would have to be "stacked" somehow on the display, in real time. The simplest way to do this would be to reverse the system used in the camera: arrange three separate black-and-white displays behind colored filters and then optically combine their images using mirrors or prisms onto a suitable screen, like frosted glass. RCA built just such a system in order to present the first electronically scanned color television demonstration on February 5, 1940, privately shown to members of the US Federal Communications Commission at the RCA plant in Camden, New Jersey. This system, however, suffered from the twin problems of costing at least three times as much as a conventional black-and-white set, as well as having very dim pictures, the result of the fairly low illumination given off by tubes of the era. Projection systems of this sort would become common decades later, however, with improvements in technology.

Another solution would be to use a single screen, but break it up into a pattern of closely spaced colored phosphors instead of an even coating of white. Three receivers would be used, each sending its output to a separate electron gun, aimed at its colored phosphor. However, this solution was not practical. The electron guns used in monochrome televisions had limited resolution, and if one wanted to retain the resolution of existing monochrome displays, the guns would have to focus on individual dots three times smaller. This was beyond the state of the art of the technology at the time.

Instead, a number of hybrid solutions were developed that combined a conventional monochrome display with a colored disk or mirror. In these systems the three colored images were sent one after each other, in either complete frames in the "field-sequential color system", or for each line in the "line-sequential" system. In both cases a colored filter was rotated in front of the display in sync with the broadcast. Since three separate images were being sent in sequence, if they used existing monochrome radio signaling standards they would have an effective refresh rate of only 20 fields, or 10 frames, a second, well into the region where flicker would become visible. In order to avoid this, these systems increased the frame rate considerably, making the signal incompatible with existing monochrome standards.

The first practical example of this sort of system was again pioneered by John Logie Baird. In 1940 he publicly demonstrated a color television combining a traditional black-and-white display with a rotating colored disk. This device was very "deep", but was later improved with a mirror folding the light path into an entirely practical device resembling a large conventional console. However, Baird was not happy with the design, and as early as 1944 had commented to a British government committee that a fully electronic device would be better.

In 1939, Hungarian engineer Peter Carl Goldmark introduced an electro-mechanical system while at CBS, which contained an Iconoscope sensor. The CBS field-sequential color system was partly mechanical, with a disc made of red, blue, and green filters spinning inside the television camera at 1,200 rpm, and a similar disc spinning in synchronization in front of the cathode ray tube inside the receiver set. The system was first demonstrated to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) on August 29, 1940, and shown to the press on September 4.

CBS began experimental color field tests using film as early as August 28, 1940, and live cameras by November 12. NBC (owned by RCA) made its first field test of color television on February 20, 1941. CBS began daily color field tests on June 1, 1941. These color systems were not compatible with existing black-and-white television sets, and as no color television sets were available to the public at this time, viewing of the color field tests was restricted to RCA and CBS engineers and the invited press. The War Production Board halted the manufacture of television and radio equipment for civilian use from April 22, 1942, to August 20, 1945, limiting any opportunity to introduce color television to the general public.

Fully electronic

As early as 1940, Baird had started work on a fully electronic system he called the "Telechrome". Early Telechrome devices used two electron guns aimed at either side of a phosphor plate. The phosphor was patterned so the electrons from the guns only fell on one side of the patterning or the other. Using cyan and magenta phosphors, a reasonable limited-color image could be obtained. Baird's demonstration on August 16, 1944, was the first example of a practical color television system. Work on the Telechrome continued and plans were made to introduce a three-gun version for full color. However, Baird's untimely death in 1946 ended the development of the Telechrome system.

Similar concepts were common through the 1940s and 1950s, differing primarily in the way they re-combined the colors generated by the three guns. The Geer tube was similar to Baird's concept, but used small pyramids with the phosphors deposited on their outside faces, instead of Baird's 3D patterning on a flat surface. The Penetron used three layers of phosphor on top of each other and increased the power of the beam to reach the upper layers when drawing those colors. The Chromatron used a set of focusing wires to select the colored phosphors arranged in vertical stripes on the tube.

FCC color

In the immediate post-war era, the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) was inundated with requests to set up new television stations. Worrying about congestion of the limited number of channels available, the FCC put a moratorium on all new licenses in 1948 while considering the problem. A solution was immediately forthcoming; rapid development of radio receiver electronics during the war had opened a wide band of higher frequencies to practical use, and the FCC set aside a large section of these new UHF bands for television broadcast. At the time, black-and-white television broadcasting was still in its infancy in the U.S., and the FCC started to look at ways of using this newly available bandwidth for color broadcasts. Since no existing television would be able to tune in these stations, they were free to pick an incompatible system and allow the older VHF channels to die off over time.

The FCC called for technical demonstrations of color systems in 1948, and the Joint Technical Advisory Committee (JTAC) was formed to study them. CBS displayed improved versions of its original design, now using a single 6 MHz channel (like the existing black-and-white signals) at 144 fields per second and 405 lines of resolution. Color Television Inc. (CTI) demonstrated its line-sequential system, while Philco demonstrated a dot-sequential system based on its beam-index tube-based "Apple" tube technology. Of the entrants, the CBS system was by far the best-developed, and won head-to-head testing every time.

While the meetings were taking place it was widely known within the industry that RCA was working on a dot-sequential system that was compatible with existing black-and-white broadcasts, but RCA declined to demonstrate it during the first series of meetings. Just before the JTAC presented its findings, on August 25, 1949, RCA broke its silence and introduced its system as well. The JTAC still recommended the CBS system, and after the resolution of an ensuing RCA lawsuit, color broadcasts using the CBS system started on June 25, 1951. By this point the market had changed dramatically; when color was first being considered in 1948 there were fewer than a million television sets in the U.S., but by 1951 there were well over 10 million. The idea that the VHF band could be allowed to "die" was no longer practical.

During its campaign for FCC approval, CBS gave the first demonstrations of color television to the general public, showing an hour of color programs daily Mondays through Saturdays, beginning January 12, 1950, and running for the remainder of the month, over WOIC in Washington, D.C., where the programs could be viewed on eight 16-inch color receivers in a public building. Due to high public demand, the broadcasts were resumed February 13–21, with several evening programs added. CBS initiated a limited schedule of color broadcasts from its New York station WCBS-TV Mondays to Saturdays beginning November 14, 1950, making ten color receivers available for the viewing public. All were broadcast using the single color camera that CBS owned. The New York broadcasts were extended by coaxial cable to Philadelphia's WCAU-TV beginning December 13, and to Chicago on January 10, making them the first network color broadcasts.

After a series of hearings beginning in September 1949, the FCC found the RCA and CTI systems fraught with technical problems, inaccurate color reproduction, and expensive equipment, and so formally approved the CBS system as the U.S. color broadcasting standard on October 11, 1950. An unsuccessful lawsuit by RCA delayed the first commercial network broadcast in color until June 25, 1951, when a musical variety special titled simply Premiere was shown over a network of five East Coast CBS affiliates. Viewing was again restricted: the program could not be seen on black-and-white sets, and Variety estimated that only thirty prototype color receivers were available in the New York area. Regular color broadcasts began that same week with the daytime series The World Is Yours and Modern Homemakers.

While the CBS color broadcasting schedule gradually expanded to twelve hours per week (but never into prime time), and the color network expanded to eleven affiliates as far west as Chicago, its commercial success was doomed by the lack of color receivers necessary to watch the programs, the refusal of television manufacturers to create adapter mechanisms for their existing black-and-white sets, and the unwillingness of advertisers to sponsor broadcasts seen by almost no one. CBS had bought a television manufacturer in April, and in September 1951, production began on the only CBS-Columbia color television model, with the first color sets reaching retail stores on September 28. However, it was too little, too late. Only 200 sets had been shipped, and only 100 sold, when CBS discontinued its color television system on October 20, 1951, ostensibly by request of the National Production Authority for the duration of the Korean War, and bought back all the CBS color sets it could to prevent lawsuits by disappointed customers. RCA chairman David Sarnoff later charged that the NPA's order had come "out of a situation artificially created by one company to solve its own perplexing problems" because CBS had been unsuccessful in its color venture.

Compatible color

While the FCC was holding its JTAC meetings, development was taking place on a number of systems allowing true simultaneous color broadcasts, "dot-sequential color systems". Unlike the hybrid systems, dot-sequential televisions used a signal very similar to existing black-and-white broadcasts, with the intensity of every dot on the screen being sent in succession.

In 1938 Georges Valensi demonstrated an encoding scheme that would allow color broadcasts to be encoded so they could be picked up on existing black-and-white sets as well. In his system the output of the three camera tubes were re-combined to produce a single "luminance" value that was very similar to a monochrome signal and could be broadcast on the existing VHF frequencies. The color information was encoded in a separate "chrominance" signal, consisting of two separate signals, the original blue signal minus the luminance (B'–Y'), and red-luma (R'–Y'). These signals could then be broadcast separately on a different frequency; a monochrome set would tune in only the luminance signal on the VHF band, while color televisions would tune in both the luminance and chrominance on two different frequencies, and apply the reverse transforms to retrieve the original RGB signal. The downside to this approach is that it required a major boost in bandwidth use, something the FCC was interested in avoiding.

RCA used Valensi's concept as the basis of all of its developments, believing it to be the only proper solution to the broadcast problem. However, RCA's early sets using mirrors and other projection systems all suffered from image and color quality problems, and were easily bested by CBS's hybrid system. But solutions to these problems were in the pipeline, and RCA in particular was investing massive sums (later estimated at $100 million) to develop a usable dot-sequential tube. RCA was beaten to the punch by the Geer tube, which used three B&W tubes aimed at different faces of colored pyramids to produce a color image. All-electronic systems included the Chromatron, Penetron and beam-index tube that were being developed by various companies. While investigating all of these, RCA's teams quickly started focusing on the shadow mask system.

In July 1938 the shadow mask color television was patented by Werner Flechsig (1900–1981) in Germany, and was demonstrated at the International radio exhibition Berlin in 1939. Most CRT color televisions used today are based on this technology. His solution to the problem of focusing the electron guns on the tiny colored dots was one of brute-force; a metal sheet with holes punched in it allowed the beams to reach the screen only when they were properly aligned over the dots. Three separate guns were aimed at the holes from slightly different angles, and when their beams passed through the holes the angles caused them to separate again and hit the individual spots a short distance away on the back of the screen. The downside to this approach was that the mask cut off the vast majority of the beam energy, allowing it to hit the screen only 15% of the time, requiring a massive increase in beam power to produce acceptable image brightness.

The first publicly announced network demonstration of a program using a "compatible color" system was an episode of NBC's Kukla, Fran and Ollie on October 10, 1949,[47] viewable in color only at the FCC. It did not receive FCC approval.

In spite of these problems in both the broadcast and display systems, RCA pressed ahead with development and was ready for a second assault on the standards by 1950.

Second NTSC

The possibility of a compatible color broadcast system was so compelling that the NTSC decided to re-form, and held a second series of meetings starting in January 1950. Having only recently selected the CBS system, the FCC heavily opposed the NTSC's efforts. One of the FCC Commissioners, R. F. Jones, went so far as to assert that the engineers testifying in favor of a compatible system were "in a conspiracy against the public interest".

Unlike the FCC approach where a standard was simply selected from the existing candidates, the NTSC would produce a board that was considerably more pro-active in development.

Starting before CBS color even got on the air, the U.S. television industry, represented by the National Television System Committee, worked in 1950–1953 to develop a color system that was compatible with existing black-and-white sets and would pass FCC quality standards, with RCA developing the hardware elements. RCA first made publicly announced field tests of the dot sequential color system over its New York station WNBT in July 1951. When CBS testified before Congress in March 1953 that it had no further plans for its own color system, the National Production Authority dropped its ban on the manufacture of color television receivers, and the path was open for the NTSC to submit its petition for FCC approval in July 1953, which was granted on December 17. The first publicly announced network demonstration of a program using the NTSC "compatible color" system was an episode of NBC's Kukla, Fran and Ollie on August 30, 1953, although it was viewable in color only at the network's headquarters. The first network broadcast to go out over the air in NTSC color was a performance of the opera Carmen on October 31, 1953.

Adoption

North America

Canada

Color broadcasts from the United States were available to Canadian population centers near the border since the mid-1950s. At the time that NTSC color broadcasting was officially introduced into Canada in 1966, less than one percent of Canadian households had a color television set. Color television in Canada was launched on the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation's (CBC) English language TV service on September 1, 1966. Private television broadcaster CTV also started color broadcasts in early September 1966. The CBC's French-language TV service, Radio-Canada, was broadcasting color programming for 15 hours a week in 1968. Full-time color transmissions started in 1974 on the CBC, with other private sector broadcasters in the country doing so by the end of the 1970s.

The following provinces and areas of Canada introduced color television by the years as stated

- Saskatchewan, Alberta, Manitoba, British Columbia, Ontario, Quebec (1966; Major networks only – private sector around 1968 to 1972)

- Newfoundland and Labrador (1967)

- Nova Scotia, New Brunswick (1968)

- Prince Edward Island (1969)

- Yukon (1971)

- Northwest Territories (including Nunavut) (1972; Major networks in large centers, many remote areas in the far north did not get color until at least 1977 and 1978)

Cuba

Cuba in 1958 became the second country in the world to introduce color television broadcasting, with Havana's Channel 12 using standards established by the NTSC Committee of United States Federal Communications Commission in 1940, and American technology patented by the American electronics company RCA, or Radio Corporation of America. But the color transmissions ended when broadcasting stations were seized in the Cuban Revolution in 1959, and did not return until 1975, using equipment acquired from Japan's NEC Corporation, and SECAM equipment from the Soviet Union, adapted for the American NTSC standard.

Mexico

Guillermo González Camarena independently invented and developed a field-sequential tricolor disk system in Mexico in the late 1930s, for which he requested a patent in México on August 19, 1940, and in the United States in 1941. González Camarena produced his color television system in his Gon-Cam laboratory for the Mexican market and exported it to the Columbia College of Chicago, which regarded it as the best system in the world. Goldmark had actually applied for a patent for the same field-sequential tricolor system in the US on September 7, 1940, while González Camarena had made his Mexican filing 19 days before, on August 19.

On August 31, 1946, González Camarena sent his first color transmission from his lab in the offices of the Mexican League of Radio Experiments at Lucerna St. No. 1, in Mexico City. The video signal was transmitted at a frequency of 115 MHz and the audio in the 40-metre band. He obtained authorization to make the first publicly announced color broadcast in Mexico, on February 8, 1963, of the program Paraíso Infantil on Mexico City's XHGC-TV, using the NTSC system that had by now been adopted as the standard for color programming.

González Camarena also invented the "simplified Mexican color TV system" as a much simpler and cheaper alternative to the NTSC system. Due to its simplicity, NASA used a modified version of the system in its Voyager mission of 1979, to take pictures and video of Jupiter.

United States

Although all-electronic color was introduced in the US in 1953, high prices and the scarcity of color programming greatly slowed its acceptance in the marketplace. The first national color broadcast (the 1954 Tournament of Roses Parade) occurred on January 1, 1954, but over the next dozen years most network broadcasts, and nearly all local programming, continued to be in black-and-white. In 1956, NBC's The Perry Como Show became the first live network television series to present a majority of episodes in color. CBS's The Big Record, starring pop vocalist Patti Page, was the first television show broadcast in color for the entire 1957–1958 season; its production costs were greater than most movies were at the time not only because of all the stars featured on the hour-long extravaganza but the extremely high-intensity lighting and electronics required for the new RCA TK-41 cameras, which were the first practical color television cameras. It was not until the mid-1960s that color sets started selling in large numbers, due in part to the color transition of 1965 in which it was announced that over half of all network prime-time programming would be broadcast in color that autumn. The first all-color prime-time season came just one year later.

NBC made the first coast-to-coast color broadcast when it telecast the Tournament of Roses Parade on January 1, 1954, with public demonstrations given across the United States on prototype color receivers by manufacturers RCA, General Electric, Philco, Raytheon, Hallicrafters, Hoffman, Pacific Mercury, and others. Two days earlier, Admiral had demonstrated to its distributors the prototype of Admiral's first color television set planned for consumer sale using the NTSC standards, priced at $1,175 (equivalent to $11,323 in 2020). It is not known when the later commercial version of this receiver was first sold. Production was extremely limited, and no advertisements for it were published in New York newspapers, nor those in Washington.

A color model from Admiral C1617A became available in the Chicago area on January 4, 1954 and appeared in various stores throughout the country, including those in Maryland on January 6, 1954, San Francisco, January 14, 1954, Indianapolis on January 17, 1954, Pittsburgh on January 25, 1954, and Oakland on January 26, 1954, among other cities thereafter. A color model from Westinghouse H840CK15 ($1,295, or equivalent to $12,480 in 2020) became available in the New York area on February 28, 1954; Only 30 sets were sold in its first month. a less expensive color model from RCA (CT-100) reached dealers in April 1954. Television's first prime time network color series was The Marriage, a situation comedy broadcast live by NBC in the summer of 1954. NBC's anthology series Ford Theatre became the first network color-filmed series that October; however, due to the high cost of the first fifteen color episodes, Ford ordered that two black-and-white episodes be filmed for every color episode. The first series to be filmed entirely in color was NBC's Norby, a sitcom that lasted 13 weeks, from January to April 1955, and was replaced by repeats of Ford Theatre's color episodes.

Early color telecasts could be preserved only on the black-and-white kinescope process introduced in 1947. It was not until September 1956 that NBC began using color film to time-delay and preserve some of its live color telecasts. Ampex introduced a color videotape recorder in 1958, which NBC used to tape An Evening with Fred Astaire, the oldest surviving network color videotape. This system was also used to unveil a demonstration of color television for the press. On May 22, 1958, President Dwight D. Eisenhower visited the WRC-TV NBC studios in Washington, D.C., and gave a speech touting the new technology's merits. His speech was recorded in color, and a copy of this videotape was given to the Library of Congress for posterity.

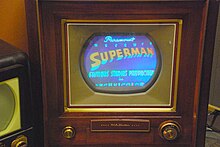

The syndicated The Cisco Kid had been filmed in color since 1949 in anticipation of color broadcasting. Several other syndicated shows had episodes filmed in color during the 1950s, including The Lone Ranger, My Friend Flicka, and Adventures of Superman. The first was carried by some stations equipped for color telecasts well before NBC began its regular weekly color dramas in 1959, beginning with the Western series Bonanza.

NBC was at the forefront of color programming because its parent company RCA manufactured the most successful line of color sets in the 1950s and, at the end of August 1956, announced that in comparison with 1955–56 (when only three of its regularly scheduled programs were broadcast in color) the 1956–57 season would feature 17 series in color. By 1959 RCA was the only remaining major manufacturer of color sets. CBS and ABC, which were not affiliated with set manufacturers and were not eager to promote their competitor's product, dragged their feet into color. CBS broadcast color specials and sometimes aired its big weekly variety shows in color, but it offered no regularly scheduled color programming until the fall of 1965. At least one CBS show, The Lucy Show, was filmed in color beginning in 1963, but continued to be telecast in black and white through the end of the 1964–65 season. ABC delayed its first color programs until 1962, but these were initially only broadcasts of the cartoon shows The Flintstones, The Jetsons and Beany and Cecil. The DuMont network, although it did have a television-manufacturing parent company, was in financial decline by 1954 and was dissolved two years later.

The relatively small amount of network color programming, combined with the high cost of color television sets, meant that as late as 1964 only 3.1 percent of television households in the US had a color set. However, by the mid-1960s, the subject of color programming turned into a ratings war. A 1965 American Research Bureau (ARB) study that proposed an emerging trend in color television set sales convinced NBC that a full shift to color would gain a ratings advantage over its two competitors. As a result, NBC provided the catalyst for rapid color expansion by announcing that its prime time schedule for fall 1965 would be almost entirely in color. ABC and CBS followed suit and over half of their combined prime-time programming also moved to color that season, but they were still reluctant to telecast all their programming in color due to production costs. All three broadcast networks were airing full color prime time schedules by the 1966–67 broadcast season, and ABC aired its last new black-and-white daytime programming in December 1967. Public broadcasting networks like NET, however, did not use color for a majority of their programming until 1968. The number of color television sets sold in the US did not exceed black-and-white sales until 1972, which was also the first year that more than fifty percent of television households in the US had a color set. This was also the year that "in color" notices before color television programs ended, due to the rise in color television set sales, and color programming having become the norm.

In a display of foresight, Disney had filmed many of its earlier shows in color so they were able to be repeated on NBC, and since most of Disney's feature-length films were also made in color, they could now also be telecast in that format. To emphasize the new feature, the series was re-dubbed Walt Disney's Wonderful World of Color, which premiered in September 1961, and retained that moniker until 1969.

By the mid-1970s, the only stations broadcasting in black-and-white were a few high-numbered UHF stations in small markets, and a handful of low-power repeater stations in even smaller markets such as vacation spots. By 1979, even the last of these had converted to color and by the early 1980s, B&W sets had been pushed into niche markets, notably low-power uses, small portable sets, or use as video monitor screens in lower-cost consumer equipment. These black-and-white displays were still compatible with color signals and remained usable through the 1990s and first decade of the 21st Century for uses that did not require a full color display. The digital television transition in the United States in 2009 rendered the remaining black-and-white television sets obsolete; all digital television receivers are capable of displaying full color.

Color broadcasting in Hawaii started on May 5, 1957. One of the last television stations in North America to convert to color, WQEX (now WINP-TV) in Pittsburgh, started broadcasting in color on October 16, 1986, after its black-and-white transmitter, which dated from the 1950s, broke down in February 1985 and the parts required to fix it were no longer available. The owner of WQEX, PBS member station WQED, used some of its pledge money to buy a color transmitter.

Early color sets were either floor-standing console models or tabletop versions nearly as bulky and heavy, so in practice, they remained firmly anchored in one place. The introduction of GE's relatively compact and lightweight Porta-Color set in the spring of 1966 made watching color television a more flexible and convenient proposition. In 1972, sales of color sets finally surpassed sales of black-and-white sets. Also in 1972, the last holdout among daytime network programs converted to color, resulting in the first completely all-color network season.

Europe

The first two color television broadcasts in Europe were made by the UK's BBC2 beginning on 1 July 1967 and West Germany's Das Erste and ZDF in August, both using the PAL system. They were followed by the Netherlands in September (PAL), and by France in October (SECAM). On 1 October 1968, the first scheduled television program in color was broadcast in Switzerland. Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Finland, Austria, East Germany, Czechoslovakia, and Hungary all started regular color broadcasts around 1969–1970. Ireland's national TV station RTÉ began using color in 1968 for recorded programs; the first outside broadcast made in color for RTÉ Television was when Ireland hosted the Eurovision Song Contest in Dublin in 1971. The PAL system spread through most of Western Europe.

More European countries introduced color television using the PAL system in the 1970s and early 1980s; examples include Belgium (1971), Bulgaria (1971, but not fully implemented until 1972), SFR Yugoslavia (1971), Spain (1972, but not fully implemented until 1977), Iceland (1973, but not fully implemented until 1976), Portugal (1975, but not fully implemented until 1980), Albania (1981), Turkey (1981) and Romania (1983, but not fully implemented until 1985–1991). In Italy there were debates to adopt a national color television system, the ISA, developed by Indesit, but that idea was scrapped. As a result, and after a test during the 1972 Summer Olympics, Italy was one of the last European countries to officially adopt the PAL system in the 1976–1977 season.

France, Luxembourg, and most of the Eastern Bloc along with their overseas territories opted for SECAM. SECAM was a popular choice in countries with much hilly terrain, and countries with a very large installed base of older monochrome equipment, which could cope much better with the greater ruggedness of the SECAM signal. However, for many countries the decision was more down to politics than technical merit.

A drawback of SECAM for production is that, unlike PAL or NTSC, certain post-production operations of encoded SECAM signals are not really possible without a significant drop in quality. As an example, a simple fade to black is trivial in NTSC and PAL: one merely reduces the signal level until it is zero. However, in SECAM the color difference signals, which are frequency modulated, need first to be decoded to e.g. RGB, then the fade-to-black is applied, and finally the resulting signal is re-encoded into SECAM. Because of this, much SECAM video editing was actually done using PAL equipment, then the resultant signal was converted to SECAM. Another drawback of SECAM is that comb filtering, allowing better color separation, is of limited use in SECAM receivers. This was not, however, much of a drawback in the early days of SECAM as such filters were not readily available in high-end TV sets before the 1990s.

The first regular color broadcasts in SECAM were started on October 1, 1967, on France's Second Channel (ORTF 2e chaîne). In France and the UK color broadcasts were made on 625-line UHF frequencies, the VHF band being used for black and white, 405 lines in UK or 819 lines in France, until the beginning of the 1980s. Countries elsewhere that were already broadcasting 625-line monochrome on VHF and UHF, simply transmitted color programs on the same channels.

Some British television programs, particularly those made by or for ITC Entertainment, were shot on color film before the introduction of color television to the UK, for the purpose of sales to US networks. The first British show to be made in color was the drama series The Adventures of Sir Lancelot (1956–57), which was initially made in black and white but later shot in color for sale to the NBC network in the United States. Other British color television programs made before the introduction of color television in the UK include Stingray (1964–1965), which was the first British TV show to be filmed entirely in color, Thunderbirds (1965–1966), The Baron (1966–1967), The Saint (from 1966 to 1969), The Avengers (from 1967 to 1969), Man in a Suitcase (1967–1968), The Prisoner (1967–1968) and Captain Scarlet and the Mysterons (1967–1968). However, most UK series predominantly made using videotape, such as Doctor Who (1963–89; 2005–present) did not begin color production until later, with the first color Doctor Who episodes not airing until 1970. (The first four, comprising the story Spearhead from Space, were shot on film owing to a technician's strike, with videotape being used thereafter.)

The last country in Europe (and in Asia and the world) to introduce color television was Georgia in 1984.

Asia and the Pacific

In Japan, NHK and NTV introduced color television, using a variation of the NTSC system (called NTSC-J) on September 10, 1960, making it the first country in Asia to introduce color television. The Philippines (1966) and Taiwan (1969) also adopted the NTSC system.

Other countries in the region instead used the PAL system, starting with Australia (1967, originally scheduled for 1972, but not fully implemented until 1975–1978), and then Thailand (1967–1969; this country converted from 525-line NTSC to 625-line PAL), Hong Kong (1967), the People's Republic of China (1971), New Zealand (1973), North Korea (1974), Singapore (1974), Pakistan (1976, but not fully implemented until 1982), Kazakhstan (1977), Vietnam (1977), Malaysia (1978, but not fully implemented until 1980), Indonesia (1979), India (1979, but not fully implemented until 1982–1986), Burma (1980), and Bangladesh (1980). South Korea did not introduce color television (using NTSC) until 1980–1981, although it was already manufacturing color television sets for export. The last country in Asia (and in Europe and the world) to introduce color television was Georgia in 1984.

Middle East

Nearly all of the countries in the Middle East use PAL. The first country in the Middle East to introduce color television was Iraq in 1967. Saudi Arabia, the United Arab Emirates, Kuwait, Bahrain, and Qatar followed in the mid-1970s, but Israel, Lebanon, and Cyprus continued to broadcast in black and white until the early 1980s. Israeli television even erased the color signals using a device called the mehikon.

Africa

The first color television service in Africa was introduced on the Tanzanian island of Zanzibar, in 1973, using PAL.[99] In 1973 also, MBC of Mauritius broadcast the OCAMM Conference, in color, using SECAM. At the time, South Africa did not have a television service at all, owing to opposition from the apartheid regime, but in 1976, one was finally launched. Nigeria adopted PAL for color transmissions in 1974 in the Benue Plateau state in the north central region of the country, but countries such as Ghana and Zimbabwe continued with black and white until 1984. The Sierra Leone Broadcasting Service (SLBS) started television broadcasting in 1963 as a cooperation between the SLBS and commercial interests; coverage was extended to all districts in 1978 when the service was also upgraded to color.

South America

Unlike most other countries in the Americas, which had adopted NTSC, Brazil began broadcasting in color using PAL-M, on February 19, 1972. Ecuador was the first South American country to broadcast in color using NTSC, on November 5, 1974. In 1978, Argentina started broadcasting in color using PAL-N in connection with the country's hosting of the FIFA World Cup. Some countries in South America, including Bolivia, Paraguay, Peru, and Uruguay, didn't broadcast full-time color television until the early 1980s.

Cor Dillen, director and later CEO of the South American branch of Philips, was responsible for bringing color television to South America.

Color standards

There are three main analog broadcast television systems in use around the world, PAL (Phase Alternating Line), NTSC (National Television System Committee), and SECAM (Séquentiel Couleur à Mémoire—Sequential Color with Memory).

The system used in The Americas and part of the Far East is NTSC. Most of Asia, Western Europe, Australia, Africa, and Eastern South America use PAL (though Brazil uses a hybrid PAL-M system). Eastern Europe and France uses SECAM. Generally, a device (such as a television) can only read or display video encoded to a standard that the device is designed to support; otherwise, the source must be converted (such as when European programs are broadcast in North America or vice versa).

[1] For SECAM the color sub-carrier alternates between 4.25000 MHz for the lines containing the Db color signal and 4.40625 MHz for the Dr signal (both are frequency modulated unlike both PAL and NTSC, which are phase modulated). The frequency of the sub-carrier is the only means that the decoder has of determining which color difference signal is actually being transmitted.

Digital television broadcasting standards, such as ATSC, DVB-T, DVB-T2, and ISDB, have superseded these analog transmission standards in many countries.