Wheeler's delayed-choice experiment is actually several thought experiments in quantum physics, proposed by John Archibald Wheeler, with the most prominent among them appearing in 1978 and 1984. These experiments are attempts to decide whether light somehow "senses" the experimental apparatus in the double-slit experiment it will travel through and adjusts its behavior to fit by assuming the appropriate determinate state for it, or whether light remains in an indeterminate state, exhibiting both wave-like and particle-like behavior until measured.

The common intention of these several types of experiments is to first do something that, according to some hidden-variable models, would make each photon "decide" whether it was going to behave as a particle or behave as a wave, and then, before the photon had time to reach the detection device, create another change in the system that would make it seem that the photon had "chosen" to behave in the opposite way. Some interpreters of these experiments contend that a photon either is a wave or is a particle, and that it cannot be both at the same time. Wheeler's intent was to investigate the time-related conditions under which a photon makes this transition between alleged states of being. His work has been productive of many revealing experiments. He may not have anticipated the possibility that other researchers would tend toward the conclusion that a photon retains both its "wave nature" and "particle nature" until the time it ends its life, e.g., by being absorbed by an electron, which acquires its energy and therefore rises to a higher-energy orbital in its atom.

This line of experimentation proved very difficult to carry out when it was first conceived. Nevertheless, it has proven very valuable over the years since it has led researchers to provide "increasingly sophisticated demonstrations of the wave–particle duality of single quanta". As one experimenter explains, "Wave and particle behavior can coexist simultaneously."

Introduction

"Wheeler's delayed-choice experiment" refers to a series of thought experiments in quantum physics, the first being proposed by him in 1978. Another prominent version was proposed in 1983. All of these experiments try to get at the same fundamental issues in quantum physics. Many of them are discussed in Wheeler's 1978 article "The 'Past' and the 'Delayed-Choice' Double-Slit Experiment", which has been reproduced in A. R. Marlow's Mathematical Foundations of Quantum Theory, pp. 9–48.

According to the complementarity principle, the 'particle-like' (like exact location) or 'wave-like' (like frequency or amplitude) properties of a photon can be measured, but not both at the same time. What characteristic is measured depends on whether experimenters use a device intended to observe particles or to observe waves. When this statement is applied very strictly, one could argue that by determining the detector type one could force the photon to become manifest only as a particle or only as a wave. Detection of a photon is generally a destructive process (see quantum nondemolition measurement for non-destructive measurements). For example, a photon can be detected as the consequences of being absorbed by an electron in a photomultiplier that accepts its energy, which is then used to trigger the cascade of events that produces a "click" from that device. In the case of the double-slit experiment, a photon appears as a highly localized point in space and time on a screen. The build up of the photons on the screen gives an indication on whether the photon must have traveled through the slits as a wave or could have traveled as a particle. The photon is said to have traveled as a wave if the build up results in the typical interference pattern of waves (see double-slit experiment#Interference of individual particles for an animation showing the build up). However, if one of the slits is closed or two orthogonal polarizers are placed in front of the slits (making the photons passing through different slits distinguishable) then no interference pattern will appear, and the build up can be explained as the result of the photon traveling as a particle.

Quantum mechanics predicts that the photon always travels as a wave, however one can only see this prediction by detecting the photon as a particle. Thus, the question arises: Could the photon decide to travel as a wave or a particle depending on the experimental setup? And if yes, when does the photon decide whether it is going to travel as a wave or as a particle? Suppose that a traditional double-slit experiment is prepared so that either of the slits can be blocked. If both slits are open and a series of photons are emitted by the laser then an interference pattern will quickly emerge on the detection screen. The interference pattern can only be explained as a consequence of wave phenomena, so experimenters can conclude that each photon "decides" to travel as a wave as soon as it is emitted. If only one slit is available then there will be no interference pattern, so experimenters may conclude that each photon "decides" to travel as a particle as soon as it is emitted, even if travel as a wave also correctly predicts the distribution of the photons in the single slit experiment.

Simple interferometer

One way to investigate the question of when a photon decides whether to act as a wave or a particle in an experiment is to use the interferometer method. Here is a simple schematic diagram of an interferometer in two configurations:

If a single photon is emitted into the entry port of the apparatus at the lower-left corner, it immediately encounters a beam-splitter. Because of the equal probabilities for transmission or reflection the photon will either continue straight ahead, be reflected by the mirror at the lower-right corner, and be detected by the detector at the top of the apparatus, or it will be reflected by the beam-splitter, strike the mirror in the upper-left corner, and emerge into the detector at the right edge of the apparatus. Observing that photons show up in equal numbers at the two detectors, experimenters generally say that each photon has behaved as a particle from the time of its emission to the time of its detection, has traveled by either one path or the other, and further affirm that its wave nature has not been exhibited.

If the apparatus is changed so that a second beam splitter is placed in the upper-right corner, then part of the beams from each path will travel to the right, where they will combine to exhibit interference on a detection screen. Experimenters must explain these phenomena as consequences of the wave nature of light. Each photon must have traveled by both paths as a wave, because if each photon traveled as a particle along just one path then the many photons sent during the experiment would not produce an interference pattern.

Since nothing else has changed from experimental configuration to experimental configuration, and since in the first case the photon is said to "decide" to travel as a particle and in the second case it is said to "decide" to travel as a wave, Wheeler wanted to know whether, experimentally, a time could be determined at which the photon made its "decision." Would it be possible to let a photon pass through the region of the first beam-splitter while there was no beam-splitter in the second position, thus causing it to "decide" to travel, and then quickly let the second beam-splitter pop up into its path? Having presumably traveled as a particle up to that moment, would the beam splitter let it pass through and manifest itself as would a particle were that second beam splitter not to be there? Or, would it behave as though the second beam-splitter had always been there? Would it manifest interference effects? And if it did manifest interference effects then to have done so it must have gone back in time and changed its "decision" about traveling as a particle to traveling as a wave. Note that Wheeler wanted to investigate several hypothetical statements by obtaining objective data.

Albert Einstein did not like these possible consequences of quantum mechanics. However, when experiments were finally devised that permitted both the double-slit version and the interferometer version of the experiment, it was conclusively shown that a photon could begin its life in an experimental configuration that would call for it to demonstrate its particle nature, end up in an experimental configuration that would call for it to demonstrate its wave nature, and that in these experiments it would always show its wave characteristics by interfering with itself. Furthermore, if the experiment was begun with the second beam-splitter in place but it was removed while the photon was in flight, then the photon would inevitably show up in a detector and not show any sign of interference effects. So the presence or absence of the second beam-splitter would always determine "wave or particle" manifestation. Many experimenters reached an interpretation of the experimental results that said that the change in final conditions would retroactively determine what the photon had "decided" to be as it was entering the first beam-splitter. As mentioned above, Wheeler rejected this interpretation.

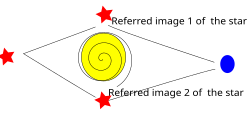

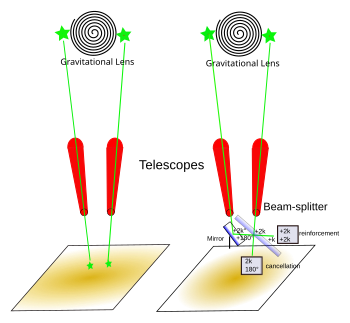

Cosmic interferometer

In an attempt to avoid destroying normal ideas of cause and effect, some theoreticians suggested that information about whether there was or was not a second beam-splitter installed could somehow be transmitted from the end point of the experimental device back to the photon as it was just entering that experimental device, thus permitting it to make the proper "decision." So Wheeler proposed a cosmic version of his experiment. In that thought experiment he asks what would happen if a quasar or other galaxy millions or billions of light years away from Earth passes its light around an intervening galaxy or cluster of galaxies that would act as a gravitational lens. A photon heading exactly towards Earth would encounter the distortion of space in the vicinity of the intervening massive galaxy. At that point it would have to "decide" whether to go by one way around the lensing galaxy, traveling as a particle, or go both ways around by traveling as a wave. When the photon arrived at an astronomical observatory at Earth, what would happen? Due to the gravitational lensing, telescopes in the observatory see two images of the same quasar, one to the left of the lensing galaxy and one to the right of it. If the photon has traveled as a particle and comes into the barrel of a telescope aimed at the left quasar image it must have decided to travel as a particle all those millions of years, or so say some experimenters. That telescope is pointing the wrong way to pick up anything from the other quasar image. If the photon traveled as a particle and went the other way around, then it will only be picked up by the telescope pointing at the right "quasar." So millions of years ago the photon decided to travel in its guise of particle and randomly chose the other path. But the experimenters now decide to try something else. They direct the output of the two telescopes into a beam-splitter, as diagrammed, and discover that one output is very bright (indicating positive interference) and that the other output is essentially zero, indicating that the incoming wavefunction pairs have self-cancelled.

Wheeler then plays the devil's advocate and suggests that perhaps for those experimental results to be obtained would mean that at the instant astronomers inserted their beam-splitter, photons that had left the quasar some millions of years ago retroactively decided to travel as waves, and that when the astronomers decided to pull their beam splitter out again that decision was telegraphed back through time to photons that were leaving some millions of years plus some minutes in the past, so that photons retroactively decided to travel as particles.

Several ways of implementing Wheeler's basic idea have been made into real experiments and they support the conclusion that Wheeler anticipated — that what is done at the exit port of the experimental device before the photon is detected will determine whether it displays interference phenomena or not. Retrocausality is a mirage.

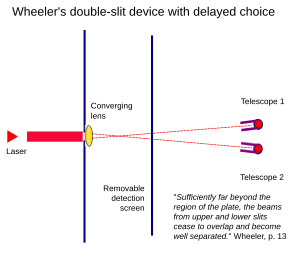

Double-slit version

A second kind of experiment resembles the ordinary double-slit experiment. The schematic diagram of this experiment shows that a lens on the far side of the double slits makes the path from each slit diverge slightly from the other after they cross each other fairly near to that lens. The result is that at the two wavefunctions for each photon will be in superposition within a fairly short distance from the double slits, and if a detection screen is provided within the region wherein the wavefunctions are in superposition then interference patterns will be seen. There is no way by which any given photon could have been determined to have arrived from one or the other of the double slits. However, if the detection screen is removed the wavefunctions on each path will superimpose on regions of lower and lower amplitudes, and their combined probability values will be much less than the unreinforced probability values at the center of each path. When telescopes are aimed to intercept the center of the two paths, there will be equal probabilities of nearly 50% that a photon will show up in one of them. When a photon is detected by telescope 1, researchers may associate that photon with the wavefunction that emerged from the lower slit. When one is detected in telescope 2, researchers may associate that photon with the wavefunction that emerged from the upper slit. The explanation that supports this interpretation of experimental results is that a photon has emerged from one of the slits, and that is the end of the matter. A photon must have started at the laser, passed through one of the slits, and arrived by a single straight-line path at the corresponding telescope.

The retrocausal explanation, which Wheeler does not accept, says that with the detection screen in place, interference must be manifested. For interference to be manifested, a light wave must have emerged from each of the two slits. Therefore, a single photon upon coming into the double-slit diaphragm must have "decided" that it needs to go through both slits to be able to interfere with itself on the detection screen (shouldn’t the detection screen be placed in front of the double slits?). For no interference to be manifested, a single photon coming into the double-slit diaphragm must have "decided" to go by only one slit because that would make it show up at the camera in the appropriate single telescope.

In this thought experiment the telescopes are always present, but the experiment can start with the detection screen being present but then being removed just after the photon leaves the double-slit diaphragm, or the experiment can start with the detection screen being absent and then being inserted just after the photon leaves the diaphragm. Some theorists argue that inserting or removing the screen in the midst of the experiment can force a photon to retroactively decide to go through the double-slits as a particle when it had previously transited it as a wave, or vice versa. Wheeler does not accept this interpretation.

The double slit experiment, like the other six idealized experiments (microscope, split beam, tilt-teeth, radiation pattern, one-photon polarization, and polarization of paired photons), imposes a choice between complementary modes of observation. In each experiment we have found a way to delay that choice of type of phenomenon to be looked for up to the very final stage of development of the phenomenon, and it depends on whichever type of detection device we then fix upon. That delay makes no difference in the experimental predictions. On this score everything we find was foreshadowed in that solitary and pregnant sentence of Bohr, "...it...can make no difference, as regards observable effects obtainable by a definite experimental arrangement, whether our plans for constructing or handling the instruments are fixed beforehand or whether we prefer to postpone the completion of our planning until a later moment when the particle is already on its way from one instrument to another."

Bohmian interpretation

One of the easiest ways of "making sense" of the delayed-choice paradox is to examine it using Bohmian mechanics. The surprising implications of the original delayed-choice experiment led Wheeler to the conclusion that "no phenomenon is a phenomenon until it is an observed phenomenon", which is a very radical position. Wheeler famously said that the "past has no existence except as recorded in the present", and that the Universe does not "exist, out there independent of all acts of observation".

However Bohm et al. (1985, Nature vol. 315, pp294–97) have shown that the Bohmian interpretation gives a straightforward account of the behaviour of the particle under the delayed-choice set up, without resorting to such a radical explanation. A detailed discussion is available in the open-source article by Basil Hiley and Callaghan, while many of the quantum paradoxes including delayed choice are summarized in Chapter 7 of the Book A Physicist's View of Matter and Mind (PVMM) using both Bohmian and standard interpretations.

In Bohm's quantum mechanics, the particle obeys classical mechanics except that its movement takes place under the additional influence of its quantum potential. A photon or an electron has a definite trajectory and passes through one or the other of the two slits and not both, just as it is in the case of a classical particle. The past is determined and stays what it was up to the moment T1 when the experimental configuration for detecting it as a wave was changed to that of detecting a particle at the arrival time T2. At T1, when the experimental set up was changed, Bohm's quantum potential changes as needed, and the particle moves classically under the new quantum potential till T2 when it is detected as a particle. Thus Bohmian mechanics restores the conventional view of the world and its past. The past is out there as an objective history unalterable retroactively by delayed choice, contrary to the radical view of Wheeler.

The "quantum potential" Q(r,T) is often taken to act instantly. But in fact, the change of the experimental set up at T1 takes a finite time dT. The initial potential. Q(r,T<T1) changes slowly over the time interval dT to become the new quantum potential Q(r,T>T1). The book PVMM referred to above makes the important observation (sec. 6.7.1) that the quantum potential contains information about the boundary conditions defining the system, and hence any change of the experimental set up is immediately recognized by the quantum potential, and determines the dynamics of the Bohmian particle.

Experimental details

John Wheeler's original discussion of the possibility of a delayed choice quantum appeared in an essay entitled "Law Without Law," which was published in a book he and Wojciech Hubert Zurek edited called Quantum Theory and Measurement, pp 182–213. He introduced his remarks by reprising the argument between Albert Einstein, who wanted a comprehensible reality, and Niels Bohr, who thought that Einstein's concept of reality was too restricted. Wheeler indicates that Einstein and Bohr explored the consequences of the laboratory experiment that will be discussed below, one in which light can find its way from one corner of a rectangular array of semi-silvered and fully silvered mirrors to the other corner, and then can be made to reveal itself not only as having gone halfway around the perimeter by a single path and then exited, but also as having gone both ways around the perimeter and then to have "made a choice" as to whether to exit by one port or the other. Not only does this result hold for beams of light, but also for single photons of light. Wheeler remarked:

The experiment in the form an interferometer, discussed by Einstein and Bohr, could theoretically be used to investigate whether a photon sometimes sets off along a single path, always follows two paths but sometimes only makes use of one, or whether something else would turn up. However, it was easier to say, "We will, during random runs of the experiment, insert the second half-silvered mirror just before the photon is timed to get there," than it was to figure out a way to make such a rapid substitution. The speed of light is just too fast to permit a mechanical device to do this job, at least within the confines of a laboratory. Much ingenuity was needed to get around this problem.

After several supporting experiments were published, Jacques et al. claimed that an experiment of theirs follows fully the original scheme proposed by Wheeler. Their complicated experiment is based on the Mach–Zehnder interferometer, involving a triggered diamond N–V colour centre photon generator, polarization, and an electro-optical modulator acting as a switchable beam splitter. Measuring in a closed configuration showed interference, while measuring in an open configuration allowed the path of the particle to be determined, which made interference impossible.

In such experiments, Einstein originally argued, it is unreasonable for a single photon to travel simultaneously two routes. Remove the half-silvered mirror at the [upper right], and one will find that the one counter goes off, or the other. Thus the photon has traveled only one route. It travels only one route. but it travels both routes: it travels both routes, but it travels only one route. What nonsense! How obvious it is that quantum theory is inconsistent!

Interferometer in the lab

The Wheeler version of the interferometer experiment could not be performed in a laboratory until recently because of the practical difficulty of inserting or removing the second beam-splitter in the brief time interval between the photon's entering the first beam-splitter and its arrival at the location provided for the second beam-splitter. This realization of the experiment is done by extending the lengths of both paths by inserting long lengths of fiber optic cable. So doing makes the time interval involved with transits through the apparatus much longer. A high-speed switchable device on one path, composed of a high-voltage switch, a Pockels cell, and a Glan–Thompson prism, makes it possible to divert that path away from its ordinary destination so that path effectively comes to a dead end. With the detour in operation, nothing can reach either detector by way of that path, so there can be no interference. With it switched off the path resumes its ordinary mode of action and passes through the second beam-splitter, making interference reappear. This arrangement does not actually insert and remove the second beam-splitter, but it does make it possible to switch from a state in which interference appears to a state in which interference cannot appear, and do so in the interval between light entering the first beam-splitter and light exiting the second beam-splitter. If photons had "decided" to enter the first beam-splitter as either waves or a particles, they must have been directed to undo that decision and to go through the system in their other guise, and they must have done so without any physical process being relayed to the entering photons or the first beam-splitter because that kind of transmission would be too slow even at the speed of light. Wheeler's interpretation of the physical results would be that in one configuration of the two experiments a single copy of the wavefunction of an entering photon is received, with 50% probability, at one or the other detectors, and that under the other configuration two copies of the wave function, traveling over different paths, arrive at both detectors, are out of phase with each other, and therefore exhibit interference. In one detector the wave functions will be in phase with each other, and the result will be that the photon has 100% probability of showing up in that detector. In the other detector the wave functions will be 180° out of phase, will cancel each other exactly, and there will be a 0% probability of their related photons showing up in that detector.

Interferometer in the cosmos

The cosmic experiment envisioned by Wheeler could be described either as analogous to the interferometer experiment or as analogous to a double-slit experiment. The important thing is that by a third kind of device, a massive stellar object acting as a gravitational lens, photons from a source can arrive by two pathways. Depending on how phase differences between wavefunction pairs are arranged, correspondingly different kinds of interference phenomena can be observed. Whether to merge the incoming wavefunctions or not, and how to merge the incoming wavefunctions can be controlled by experimenters. There are none of the phase differences introduced into the wavefunctions by the experimental apparatus as there are in the laboratory interferometer experiments, so despite there being no double-slit device near the light source, the cosmic experiment is closer to the double-slit experiment. However, Wheeler planned for the experiment to merge the incoming wavefunctions by use of a beam splitter.

The main difficulty in performing this experiment is that the experimenter has no control over or knowledge of when each photon began its trip toward earth, and the experimenter does not know the lengths of each of the two paths between the distant quasar. Therefore, it is possible that the two copies of one wavefunction might well arrive at different times. Matching them in time so that they could interact would require using some kind of delay device on the first to arrive. Before that task could be done, it would be necessary to find a way to calculate the time delay.

One suggestion for synchronizing inputs from the two ends of this cosmic experimental apparatus lies in the characteristics of quasars and the possibility of identifying identical events of some signal characteristic. Information from the Twin Quasars that Wheeler used as the basis of his speculation reach earth approximately 14 months apart. Finding a way to keep a quantum of light in some kind of loop for over a year would not be easy.

Double-slits in lab and cosmos

Wheeler's version of the double-slit experiment is arranged so that the same photon that emerges from two slits can be detected in two ways. The first way lets the two paths come together, lets the two copies of the wavefunction overlap, and shows interference. The second way moves farther away from the photon source to a position where the distance between the two copies of the wavefunction is too great to show interference effects. The technical problem in the laboratory is how to insert a detector screen at a point appropriate to observe interference effects or to remove that screen to reveal the photon detectors that can be restricted to receiving photons from the narrow regions of space where the slits are found. One way to accomplish that task would be to use the recently developed electrically switchable mirrors and simply change directions of the two paths from the slits by switching a mirror on or off. As of early 2014 no such experiment has been announced.

The cosmic experiment described by Wheeler has other problems, but directing wavefunction copies to one place or another long after the photon involved has presumably "decided" whether to be a wave or a particle requires no great speed at all. One has about a billion years to get the job done.

The cosmic version of the interferometer experiment could easily be adapted to function as a cosmic double-slit device as indicated in the illustration. Wheeler appears not to have considered this possibility. It has, however, been discussed by other writers.

Current experiments of interest

The first real experiment to follow Wheeler's intention for a double-slit apparatus to be subjected to end-game determination of detection method is the one by Walborn et al.

Researchers with access to radio telescopes originally designed for SETI research have explicated the practical difficulties of conducting the interstellar Wheeler experiment.

A recent experiment by Manning et al. confirms the standard predictions of standard quantum mechanics with an atom of Helium.

Conclusions

Ma, Zeilinger et al. have summarized what can be known as a result of experiments that have arisen from Wheeler's proposals. They say:

Any explanation of what goes on in a specific individual observation of one photon has to take into account the whole experimental apparatus of the complete quantum state consisting of both photons, and it can only make sense after all information concerning complementary variables has been recorded. Our results demonstrate that the viewpoint that the system photon behaves either definitely as a wave or definitely as a particle would require faster-than-light communication. Because this would be in strong tension with the special theory of relativity, we believe that such a viewpoint should be given up entirely.