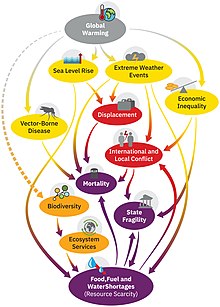

The effects of climate change on human health are increasingly well studied and quantified.They fall into three main categories: (i) direct effects (e.g. due to heat waves, extreme weather events), (ii) impacts from climate-related changes in ecological systems and relationships (e.g. crop yields, marine productivity), and (iii) the more indirect consequences such as impoverishment, displacement, and mental health problems.

More specifically, the relationship between health and heat includes the following main aspects: exposure of vulnerable populations to heatwaves, heat-related mortality, reduced labour capacity for outdoor workers and impacts on mental health. There is a range of climate-sensitive infectious diseases which may increase in some regions, such as mosquito-borne diseases, cholera and some waterborne diseases. Health is also acutely impacted by extreme weather events (floods, hurricanes, droughts, wildfires) through injuries, diseases, and air pollution in the case of wildfires. Other indirect health impacts from climate change may be rising food insecurity, undernutrition and water insecurity. Climate change will also impact where diseases are moving in the future. Many infectious diseases are predicted to spread to new geographic areas with naïve immune systems.

Disadvantaged populations are especially vulnerable to climate change impacts. For example, young children and older people are the most vulnerable to extreme heat.

The health effects of climate change are increasingly a matter of concern for the international public health policy community. Already in 2009, a publication in the well-known general medical journal The Lancet stated: "Climate change is the biggest global health threat of the 21st century". This was re-iterated in 2015 by a statement of the World Health Organisation. In 2019, the Australian Medical Association formally declared climate change a health emergency.

Studies have found that communication on climate change is more likely to lead to engagement by the public if it is framed as a health concern, rather than just as an environmental matter.

Background

Effects of climate change

Climate change affects the physical environment, ecosystems and human societies. Changes in the climate system include an overall warming trend, more extreme weather and rising sea levels. These in turn impact nature and wildlife, as well as human settlements and societies. The effects of human-caused climate change are broad and far-reaching, especially if significant climate action is not taken. The projected and observed negative impacts of climate change are sometimes referred to as the climate crisis.

The changes in climate are not uniform across the Earth. In particular, most land areas have warmed faster than most ocean areas, and the Arctic is warming faster than most other regions. Among the effects of climate change on oceans are an increase of ocean temperatures, a rise in sea level from ocean warming and ice sheet melting, increased ocean stratification, and changes to ocean currents including a weakening of the Atlantic meridional overturning circulation. Carbon dioxide from the atmosphere is acidifiying the ocean.

Recent warming has strongly affected natural biological systems. It has degraded land by raising temperatures, drying soils and increasing wildfire risk. Species worldwide are migrating poleward to colder areas. On land, many species move to higher ground, whereas marine species seek colder water at greater depths. At 2 °C (3.6 °F) of warming, around 10% of species on land would become critically endangered.Climate change vulnerability

A 2021 report published in The Lancet found that climate change does not affect people's health in an equal way. The greatest impact tends to fall on the most vulnerable such as the poor, women, children, the elderly, people with pre-existing health concerns, other minorities and outdoor workers.

There are certain predictors for health patterns of people which will determine the social vulnerability of the individuals. These can be grouped into "demographic, socioeconomic, housing, health (such as pre-existing health conditions), neighbourhood, and geographical factors".

Types of pathways affecting health

Climate change is linked with health outcomes via three main pathways:

- Direct mechanisms or risks: changes in extreme weather and resultant increased storms, floods, droughts, heat waves (wildfires also fit here)

- Indirect mechanisms or risks: these are mediated through changes in the biosphere (e.g., in the burden of disease and distribution of disease vectors, or food availability, water quality, air pollution, land use change, ecological change)

- Social dynamics (age and gender, health status, socioeconomic status, social capital, public health infrastructure, mobility and conflict status)

These health risks vary across the world. For example, differences in health service provision or economic development will result in different health risks for people in different regions.

Overview of health impacts

General health impacts

The direct, indirect and social dynamic effects of climate change on health and wellbeing produce the following health impacts: cardiovascular diseases, respiratory diseases, infectious diseases, undernutrition, mental illness, allergies, injuries and poisoning.

Health and health care provision can also be impacted by the collapse of health systems due to climate-induced events such as flooding. Therefore, building health systems that are climate resilient is a priority.

Mental health impacts

The effects of climate change on mental health and well-being can be negative, especially for vulnerable populations and those with pre-existing serious mental illness. There are three broad pathways by which these effects can take place: directly, indirectly or via awareness. The direct pathway includes stress related conditions being caused by exposure to extreme weather events, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Scientific studies have linked mental health outcomes to several climate-related exposures—heat, humidity, rainfall, drought, wildfires and floods. The indirect pathway can be via disruption to economic and social activities, such as when an area of farmland is less able to produce food. The third pathway can be of mere awareness of the climate change threat, even by individuals who are not otherwise affected by it.

Mental health outcomes have been measured in several studies through indicators such as psychiatric hospital admissions, mortality, self-harm and suicide rates. Vulnerable populations and life stages include people with pre-existing mental illness, Indigenous peoples, children and adolescents. The emotional responses to the threat of climate change can include eco-anxiety, ecological grief and eco-anger. Such emotions can be rational responses to the degradation of the natural world and lead to adaptive action.

Assessing the exact mental health effects of climate change is difficult; increases in heat extremes pose risks to mental health which can manifest themselves in increased mental health-related hospital admissions and suicidality.Impacts caused by heat

Impacts of higher global temperatures will have ramifications for the following aspects: vulnerability to extremes of heat, exposure of vulnerable populations to heatwaves, heat and physical activity, change in labor capacity, heat and sentiment (mental health), heat-related mortality.

The global average and combined land and ocean surface temperature show a warming of 1.09 °C (range: 0.95 to 1.20 °C) from 1850–1900 to 2011–2020, based on multiple independently produced datasets. The trend is faster since 1970s than in any other 50-year period over at least the last 2000 years.

Vulnerable people with regard to heat illnesses include people with low incomes, minority groups, women (in particular pregnant women), children, older adults (over 65 years old), people with chronic diseases, disabilities and co-morbidities. Further people at risk include those in urban environments (due to the urban heat island effect), outdoor workers and people who take certain prescription drugs. Exposure to extreme heat poses an acute health hazard for many of the people deemed as vulnerable.

Climate change increases the frequency and severity of heatwaves and thus heat stress for people. Human responses to heat stress can include heat stroke and hyperthermia. Extreme heat is also linked to low quality sleep, acute kidney injury and complications with pregnancy. Furthermore, it may cause the deterioration of pre-existing cardiovascular and respiratory disease. Adverse pregnancy outcomes due to high ambient temperatures include for example low birth weight and pre-term birth. Heat waves have also resulted in epidemics of chronic kidney disease (CKD). Prolonged heat exposure, physical exertion, and dehydration are sufficient factors for the development of CKD.

The human body requires evaporative cooling to prevent overheating, even with a low activity level. With excessive ambient heat and humidity during heatwaves, adequate evaporative cooling might be compromised.

A wet-bulb temperature that is too high means that human bodies would no longer be able to adequately cool the skin. A wet bulb temperature of 35 °C is regarded as the limit for humans (called the "physiological threshold for human adaptability" to heat and humidity). As of 2020, only two weather stations had recorded 35 °C wet-bulb temperatures, and only very briefly, but the frequency and duration of these events is expected to rise with ongoing climate change. Global warming above 1.5 degrees risks making parts of the tropics uninhabitable because the threshold for the wet bulb temperature may be passed.

People with cognitive health issues (e.g. depression, dementia, Parkinson's disease) are more at risk when faced with high temperatures and ought to be extra careful. as cognitive performance has been shown to be differentially affected by heat. People with diabetes, are overweight, have sleep deprivation, or have cardiovascular/cerebrovascular conditions should avoid too much heat exposure.

The risk of dying from chronic lung disease during a heat wave has been estimated at 1.8-8.2% higher compared to average summer temperatures. An 8% increase in hospitalization rate for people with COPD has been estimated for every 1 °C increase in temperatures above 29 °C.

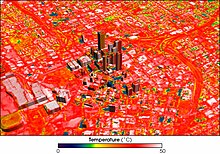

In urban areas

The effects of heatwaves tend to be more pronounced in urban areas because they are typically warmer than surrounding rural areas due to the urban heat island effect. This is caused from the way many cities are built. For example, they often have extensive areas of asphalt, reduced greenery along with many large heat-retaining buildings that physically block cooling breezes and ventilation. Lack of water features are another cause.

Extreme heat exposure in cities with a wet bulb globe temperature above 30 °C tripled between 1983 and 2016. It increased by about 50% when the population growth in these cities is not taken into account.

Cities are often on the front-line of climate impacts due to their densely concentrated populations, the urban heat island effect, their frequent proximity to coasts and waterways, and reliance on ageing physical infrastructure networks.

Health experts warn that "exposure to extreme heat increases the risk of death from cardiovascular, cerebrovascular, and respiratory conditions and all-cause mortality. Heat-related deaths in people older than 65 years reached a record high of an estimated 345 000 deaths in 2019".

More than 70,000 Europeans died as a result of the 2003 European heat wave. Also more than 2,000 people died in Karachi, Pakistan in June 2015 due to a severe heat wave with temperatures as high as 49 °C (120 °F).

Increasing access to indoor cooling (air conditioning) will help prevent heat-related mortality but current air conditioning technology is generally unsustainable as it contributes to greenhouse gas emissions, air pollution, peak electricity demand, and urban heat islands.

Mortality due to heat waves could be reduced if buildings were better designed to modify the internal climate, or if the occupants were better educated about the issues, so they can take action on time. Heatwave early warning and response systems are important elements of heat action plans.

Reduced labour capacity

Heat exposure can affect people's ability to work. The annual Countdown Report by The Lancet investigated change in labour capacity as an indicator. It found that during 2021, high temperature reduced global potential labour hours by 470 billion - a 37% increase compared to the average annual loss that occurred during the 1990s. Occupational heat exposure affects especially laborers in the agricultural sector of developing countries. In those countries, the vast majority of these labour hour losses (87%) were in the agricultural sector.

Working in extreme heat can lead to labor force productivity decreases as well as participation because employees' health may be weaker due to heat related health problems, such as dehydration, fatigue, dizziness, and confusion.

Sports and outdoor exercise

With regards to sporting activities it has been observed that "hot weather reduces the likelihood of engaging in exercise" Furthermore, participating in sports during excessive heat can lead to injury or even death. It is also well established that regular physical activity is beneficial for human health, including mental health. Therefore, an increase in hot days due to climate change could indirectly affect mental health due to people exercising less.

However, the evidence on hours of outdoor exercise is still weak: A review in 2021 reported data on the increase of hours per year during which temperatures were too high for safe outdoor exercise (Indicator 1.1.3). But the follow-up review in the following year did not report the same kind of data but reported an increase in "hours of moderate risk of heat stress during light outdoor physical activity".

Impacts caused by weather and climate events other than heat

Climate change is increasing the periodicity and intensity of some extreme weather events. Confidence in the attribution of extreme weather to anthropogenic climate change is highest in changes in frequency or magnitude of extreme heat and cold events with some confidence in increases in heavy precipitation and increases in the intensity of droughts.

Extreme weather events, such as floods, hurricanes, droughts and wildfires can result in injuries, death and the spread of infectious diseases. For example, local epidemics can occur due to loss of infrastructure, such as hospitals and sanitation services, but also because of changes in local ecology and environment.

Floods

Due to an increase in heavy rainfall events, floods are expected to become more severe in future when they do occur. However, the interactions between rainfall and flooding are complex. There are in fact some regions in which flooding is expected to become rarer. This depends on several factors, such as changes in rain and snowmelt, but also soil moisture. Floods have short and long-term negative implications to people's health and well-being. Short term implications include mortalities, injuries and diseases, while long term implications include non-communicable diseases and psychosocial health aspects.

For example, in the 2022 Pakistan Floods (which were likely more severe because of climate change) people's health was affected through various direct and indirect ways. There were outbreaks of diseases like malaria, dengue, and other skin diseases.

Hurricanes and thunderstorms

Stronger hurricanes create more opportunities for vectors to breed and infectious diseases to flourish. Extreme weather also means stronger winds. These winds can carry vectors tens of thousands of kilometers, resulting in an introduction of new infectious agents to regions that have never seen them before, making the humans in these regions even more susceptible.

Another result of hurricanes is increased rainwater, which promotes flooding. Hurricanes result in ruptured pollen grains, which releases respirable aeroallergens. Thunderstorms cause a concentration of pollen grains at the ground level, which causes an increase in the release of allergenic particles in the atmosphere due to rupture by osmotic shock. Around 20–30 minutes after a thunderstorm, there is an increased risk for people with pollen allergies to experience severe asthmatic exacerbations, due to high concentration inhalation of allergenic peptides.

Droughts

Climate change affects multiple factors associated with droughts, such as how much rain falls and how fast the rain evaporates again. Warming over land increases the severity and frequency of droughts around much of the world. Many of the consequences of droughts have impacts on human health. This can be through destruction of food supply (loss of crop yields), malnutrition and with this, dozens of associated diseases and health problems.

Wildfires

Climate change increases wildfire potential and activity. Climate change leads to a warmer ground temperature and its effects include earlier snowmelt dates, drier than expected vegetation, increased number of potential fire days, increased occurrence of summer droughts, and a prolonged dry season.

Wood smoke from wildfires produces particulate matter that has damaging effects to human health. The primary pollutants in wood smoke are carbon monoxide and nitric oxide. Through the destruction of forests and human-designed infrastructure, wildfire smoke releases other toxic and carcinogenic compounds, such as formaldehyde and hydrocarbons. These pollutants damage human health by evading the mucociliary clearance system and depositing in the upper respiratory tract, where they exert toxic effects.

The health effects of wildfire smoke exposure include exacerbation and development of respiratory illness such as asthma and chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder; increased risk of lung cancer, mesothelioma and tuberculosis; increased airway hyper-responsiveness; changes in levels of inflammatory mediators and coagulation factors; and respiratory tract infection.

Health risks due to climate-sensitive infectious diseases

Infectious diseases that are sensitive to climate can be grouped into: vector-borne diseases (transmitted via mosquitos, ticks etc.), water-borne diseases and food-borne diseases. Climate change is affecting the distribution of all these diseases. This occurs for example via expanding the geographic range and seasonality of these diseases and their vectors.

Climate change may also lead to new infectious diseases due to changes in microbial and vector geographic range. Microbes that are harmful to humans can adapt to higher temperatures, which will allow them to build better tolerance against human endothermy defenses.

Vector-borne diseases

Mosquito-borne diseases

Mosquito-borne diseases that are sensitive to climate include for example malaria, elephantiasis, Rift Valley fever, yellow fever, dengue fever, Zika virus, and chikungunya. Scientists found in 2022 that rising temperatures are increasing the areas where dengue fever, malaria and other mosquito-carried diseases are able to spread. Warmer temperatures are also advancing to higher elevations, allowing mosquitoes to survive in places that were previously inhospitable to them. This risks malaria making a return to areas where it was previously eradicated.

Diseases from ticks

Ticks are changing their geographic range because of rising temperatures, and this puts new populations at risk. Ticks can spread lyme disease and tick-borne encephalitis. It is expected that climate change will increase the incidence of these diseases in the Northern Hemisphere. For example, a review of the literature found that "In the USA, a 2°C warming could increase the number of Lyme disease cases by over 20% over the coming decades and lead to an earlier onset and longer length of the annual Lyme disease season".

Waterborne diseases

There are a range of waterborne diseases and parasites that will pose greater health risks in future. This will vary by region. For example, in Africa Cryptosporidium spp. and Giardia duodenalis (two protozoan parasites) will increase. This is due to increasing temperatures and drought.

Scientist expect that disease outbreaks caused by vibrio (in particular the bacterium that causes cholera, which is called vibrio cholerae) are increasing in occurrence and intensity. One reason is that the area of coastline with suitable conditions for vibrio bacteria has increased due to changes in sea surface temperature and sea surface salinity caused by climate change. These pathogens can cause gastroenteritis, cholera, wound infections, and sepsis. It has been observed that in the period of 2011–21, the "area of coastline suitable for Vibrio bacterial transmission has increased by 35% in the Baltics, 25% in the Atlantic Northeast, and 4% in the Pacific Northwest. Furthermore, the increasing occurrence of higher temperature days, heavy rainfall events and flooding due to climate change could lead to an increase in cholera risks.

Other health risks influenced by climate change

Harmful algal blooms in oceans and lakes

The warming oceans and lakes are leading to more frequent harmful algal blooms. Also, during droughts, surface waters are even more susceptible to harmful algal blooms and microorganisms. Algal blooms increase water turbidity, suffocating aquatic plants, and can deplete oxygen, killing fish. Some kinds of blue-green algae (cyanobacteria) create neurotoxins, hepatoxins, cytotoxins or endotoxins that can cause serious and sometimes fatal neurological, liver and digestive diseases in humans. Cyanobacteria grow best in warmer temperatures (especially above 25 degrees Celsius), and so areas of the world that are experiencing general warming as a result of climate change are also experiencing harmful algal blooms more frequently and for longer periods of time.

One of these toxin producing algae is Pseudo-nitzschia fraudulenta. This species produces a substance called domoic acid which is responsible for amnesic shellfish poisoning. The toxicity of this species has been shown to increase with greater CO2 concentrations associated with ocean acidification. Some of the more common illnesses reported from harmful algal blooms include; Ciguatera fish poisoning, paralytic shellfish poisoning, azaspiracid shellfish poisoning, diarrhetic shellfish poisoning, neurotoxic shellfish poisoning and the above-mentioned amnesic shellfish poisoning.

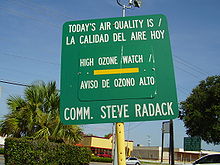

The relationship between surface ozone (also called ground-level ozone) and ambient temperature is complex. Changes in air temperature and water content affect the air's chemistry and the rates of chemical reactions that create and remove ozone. Many chemical reaction rates increase with temperature and lead to increased ozone production. Climate change projections show that rising temperatures and water vapour in the atmosphere will likely increase surface ozone in polluted areas like the eastern United States.

On the other hand, ozone concentrations could decrease in a warming climate if anthropogenic ozone-precursor emissions (e.g., nitrogen oxides) continue to decrease through implementation of policies and practices. Therefore, future surface ozone concentrations depend on the climate change mitigation steps taken (more or less methane emissions) as well as air pollution control steps taken.

High surface ozone concentrations often occur during heat waves in the United States. Throughout much of the eastern United States, ozone concentrations during heat waves are at least 20% higher than the summer average. Broadly speaking, surface ozone levels are higher in cities with high levels of air pollution. Ozone pollution in urban areas affects denser populations, and is worsened by high populations of vehicles, which emit pollutants NO2 and VOCs, the main contributors to problematic ozone levels.

There is a great deal of evidence to show that surface ozone can harm lung function and irritate the respiratory system. Exposure to ozone (and the pollutants that produce it) is linked to premature death, asthma, bronchitis, heart attack, and other cardiopulmonary problems. High ozone concentrations irritate the lungs and thus affect respiratory function, especially among people with asthma. People who are most at risk from breathing in ozone air pollution are those with respiratory issues, children, older adults and those who typically spend long periods of time outside such as construction workers.

Carbon dioxide levels and human cognition

Higher levels of indoor and outdoor CO2 levels may impair human cognition.

Pollen allergies

A warming climate can lead to increases of pollen season lengths and concentrations in some regions of the world. For example, in northern mid-latitudes regions, the spring pollen season is now starting earlier. This can affect people with pollen allergies (hay fever). The rise in pollen also comes from rising CO2 concentrations in the atmosphere and resulting CO2 fertilisation effects.

Violence and conflicts

Climate change may increase the risk of violent conflict, which can lead to injuries, such as battle injuries, and death. Conflict can result from the increased propensity towards violence after people become more irritable due to excessive heat. There can also be follow-on effects on health from resource scarcity or human migrations that climate change can cause or aggravate in already conflict prone areas.

However, the observed contribution of climate change to conflict risk is small in comparison with cultural, socioeconomic, and political causes. There is some evidence that rural-to-urban migration within countries worsens the conflict risk in violence prone regions. But there is no evidence that migration between countries would increase the risk of violence.

Accidents

Researchers found that there is a strong correlation between higher winter temperatures and drowning accidents in large lakes, because the ice gets thinner and weaker.

Available evidence on the effect of climate change on the epidemiology of snakebite is limited but it is expected that there will be a geographic shift in risk of snakebite: northwards in North America and southwards in South America and in Mozambique, and increase in incidence of bite in Sri Lanka.

Health risks from food and water insecurity

Climate change affects many aspects of food security through "multiple and interconnected pathways". Many of these are related to the effects of climate change on agriculture, for example failed crops due to more extreme weather events. This comes on top of other coexisting crises that reduce food security in many regions. Less food security means more undernutrition with all its associated health problems. Food insecurity is increasing at the global level (some of the underlying causes are related to climate change, others are not) and about 720–811 million people suffered from hunger in 2020.

The number of deaths resulting from climate change-induced changes to food availability are difficult to estimate. The 2022 IPCC Sixth Assessment Report does not quantify this number in its chapter on food security. A modelling study from 2016 found "a climate change–associated net increase of 529,000 adult deaths worldwide [...] from expected reductions in food availability (particularly fruit and vegetables) by 2050, as compared with a reference scenario without climate change."

Reduced nutritional value of crops

Food production from the oceans

A headline finding in 2021 regarding marine food security stated that: "In 2018–20, nearly 70% of countries showed increases in average sea surface temperature in their territorial waters compared within 2003–05, reflecting an increasing threat to their marine food productivity and marine food security".

Water insecurity

Access to clean drinking water and sanitation is important for healthy living and well-being.

Potential health benefits

Health co-benefits from mitigation

The health benefits (also called "co-benefits") from climate change mitigation measures are significant: potential measures can not only mitigate future health impacts from climate change but also improve health directly. Climate change mitigation is interconnected with various co-benefits (such as reduced air pollution and associated health benefits) and how it is carried out (in terms of e.g. policymaking) could also determine its impacts on living standards (whether and how inequality and poverty are reduced).

There are many health co-benefits associated with climate action. These include those of cleaner air, healthier diets (e.g. less red meat), more active lifestyles, and increased exposure to green urban spaces. Access to urban green spaces provides benefits to mental health as well.

Compared with the current pathways scenario (with regards to greenhouse gas emissions and mitigation efforts), the "sustainable pathways scenario" will likely result in an annual reduction of 1.18 million air pollution-related deaths, 5.86 million diet-related deaths, and 1.15 million deaths due to physical inactivity, across the nine countries, by 2040. These benefits were attributable to the mitigation of direct greenhouse gas emissions and the commensurate actions that reduce exposure to harmful pollutants, as well as improved diets and safe physical activity. Air pollution generated by fossil fuel combustion is both a major driver of global warming and the cause of a large number of annual deaths with some estimates as high as 8.7 million excess deaths during 2018.

Placing health as a key focus of the Nationally Determined Contributions could present an opportunity to increase ambition and realize health co-benefits.

Potential health benefits from global warming

It is possible that a potential health benefit from global warming could result from fewer cold days in winter: This could lead to some mental health benefits. However, the evidence on this correlation is regarded as inconsistent in 2022.

Global estimates

Estimating deaths (mortality) or DALYs (morbidity) from the effects of climate change at the global level is very difficult. A 2014 study by the World Health Organization tried to do this and estimated the effect of climate change on human health, but not all of the effects of climate change were included in their estimates. For example, the effects of more frequent and extreme storms were excluded. They did assess deaths from heat exposure in elderly people, increases in diarrhea, malaria, dengue, coastal flooding, and childhood undernutrition. The authors estimated that climate change was projected to cause an additional 250,000 deaths per year between 2030 and 2050 but also stated that "these numbers do not represent a prediction of the overall impacts of climate change on health, since we could not quantify several important causal pathways".

Climate change was responsible for 3% of diarrhoea, 3% of malaria, and 3.8% of dengue fever deaths worldwide in 2004. Total attributable mortality was about 0.2% of deaths in 2004; of these, 85% were child deaths. The effects of more frequent and extreme storms were excluded from this study.

The health impacts of climate change are expected to rise in line with projected ongoing global warming for different climate change scenarios.

Society and culture

Climate justice and climate migrants

Much of the health burden associated with climate change falls on vulnerable people (e.g. indigenous peoples and economically disadvantaged communities). As a result, people of disadvantaged sociodemographic groups experience unequal risks. Often these people will have made a disproportionately low contribution toward man-made global warming, thus leading to concerns over climate justice.

Climate change has diverse impacts on migration activities, and can lead to decreases or increases in the number of people who migrate. Migration activities can have impacts on health and well-being, in particular for mental health. Migration in the context of climate change can be grouped into four types: adaptive migration (see also climate change adaptation), involuntary migration, organised relocation of populations, and immobility (which is when people are unable or unwilling to move even though it is recommended).

Communication strategies

Studies have found that when communicating climate change with the public, it can help encourage engagement if it is framed as a health concern, rather than as an environmental issue. This is especially the case when comparing a health related framing to one that emphasised environmental doom, as was common in the media at least up until 2017. Communicating the co-benefits to health helps underpin greenhouse gas reduction strategies. Safeguarding health—particularly of the most vulnerable—is a frontline local climate change adaptation goal.

Policy responses

Due to its significant impact on human health, climate change has become a major concern for public health policy. The United States Environmental Protection Agency had issued a 100-page report on global warming and human health back in 1989. By the early years of the 21st century, climate change was increasingly addressed as a public health concern at a global level, for example in 2006 at Nairobi by UN secretary general Kofi Annan. Since 2018, factors such as the 2018 heat wave, the Greta effect and the October 2018 IPCC 1.5 °C report further increased the urgency for responding to climate change as a global health issue.

The World Bank has suggested a framework that can strengthen health systems to make them more resilient and climate-sensitive.