The relativistic Doppler effect is the change in frequency, wavelength and amplitude of light, caused by the relative motion of the source and the observer (as in the classical Doppler effect), when taking into account effects described by the special theory of relativity.

The relativistic Doppler effect is different from the non-relativistic Doppler effect as the equations include the time dilation effect of special relativity and do not involve the medium of propagation as a reference point. They describe the total difference in observed frequencies and possess the required Lorentz symmetry.

Astronomers know of three sources of redshift/blueshift: Doppler shifts; gravitational redshifts (due to light exiting a gravitational field); and cosmological expansion (where space itself stretches). This article concerns itself only with Doppler shifts.

Summary of major results

In the following table, it is assumed that for the receiver and the source are moving away from each other, being the relative velocity and the speed of light, and .

Derivation

Relativistic longitudinal Doppler effect

Relativistic Doppler shift for the longitudinal case, with source and receiver moving directly towards or away from each other, is often derived as if it were the classical phenomenon, but modified by the addition of a time dilation term. This is the approach employed in first-year physics or mechanics textbooks such as those by Feynman or Morin.

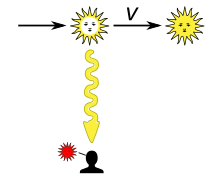

Following this approach towards deriving the relativistic longitudinal Doppler effect, assume the receiver and the source are moving away from each other with a relative speed as measured by an observer on the receiver or the source (The sign convention adopted here is that is negative if the receiver and the source are moving towards each other).

Consider the problem in the reference frame of the source.

Suppose one wavefront arrives at the receiver. The next wavefront is then at a distance away from the receiver (where is the wavelength, is the frequency of the waves that the source emits, and is the speed of light).

The wavefront moves with speed , but at the same time the receiver moves away with speed during a time , which is the period of light waves impinging on the receiver, as observed in the frame of the source. So,

Thus far, the equations have been identical to those of the classical Doppler effect with a stationary source and a moving receiver.

However, due to relativistic effects, clocks on the receiver are time dilated relative to clocks at the source: , where is the Lorentz factor. In order to know which time is dilated, we recall that is the time in the frame in which the source is at rest. The receiver will measure the received frequency to be

- Eq. 1:

The ratio

is called the Doppler factor of the source relative to the receiver. (This terminology is particularly prevalent in the subject of astrophysics: see relativistic beaming.)

The corresponding wavelengths are related by

- Eq. 2:

Identical expressions for relativistic Doppler shift are obtained when performing the analysis in the reference frame of the receiver with a moving source. This matches up with the expectations of the principle of relativity, which dictates that the result can not depend on which object is considered to be the one at rest. In contrast, the classic nonrelativistic Doppler effect is dependent on whether it is the source or the receiver that is stationary with respect to the medium.

Transverse Doppler effect

Suppose that a source and a receiver are both approaching each other in uniform inertial motion along paths that do not collide. The transverse Doppler effect (TDE) may refer to (a) the nominal blueshift predicted by special relativity that occurs when the emitter and receiver are at their points of closest approach; or (b) the nominal redshift predicted by special relativity when the receiver sees the emitter as being at its closest approach. The transverse Doppler effect is one of the main novel predictions of the special theory of relativity.

Whether a scientific report describes TDE as being a redshift or blueshift depends on the particulars of the experimental arrangement being related. For example, Einstein's original description of the TDE in 1907 described an experimenter looking at the center (nearest point) of a beam of "canal rays" (a beam of positive ions that is created by certain types of gas-discharge tubes). According to special relativity, the moving ions' emitted frequency would be reduced by the Lorentz factor, so that the received frequency would be reduced (redshifted) by the same factor.

On the other hand, Kündig (1963) described an experiment where a Mössbauer absorber was spun in a rapid circular path around a central Mössbauer emitter. As explained below, this experimental arrangement resulted in Kündig's measurement of a blueshift.

Source and receiver are at their points of closest approach

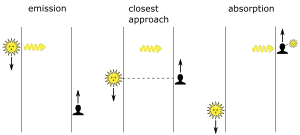

In this scenario, the point of closest approach is frame-independent and represents the moment where there is no change in distance versus time. Figure 2 demonstrates that the ease of analyzing this scenario depends on the frame in which it is analyzed.

- Fig. 2a. If we analyze the scenario in the frame of the receiver, we find that the analysis is more complicated than it should be. The apparent position of a celestial object is displaced from its true position (or geometric position) because of the object's motion during the time it takes its light to reach an observer. The source would be time-dilated relative to the receiver, but the redshift implied by this time dilation would be offset by a blueshift due to the longitudinal component of the relative motion between the receiver and the apparent position of the source.

- Fig. 2b. It is much easier if, instead, we analyze the scenario from the frame of the source. An observer situated at the source knows, from the problem statement, that the receiver is at its closest point to him. That means that the receiver has no longitudinal component of motion to complicate the analysis. (i.e. dr/dt = 0 where r is the distance between receiver and source) Since the receiver's clocks are time-dilated relative to the source, the light that the receiver receives is blue-shifted by a factor of gamma. In other words,

- Eq. 3:

Receiver sees the source as being at its closest point

This scenario is equivalent to the receiver looking at a direct right angle to the path of the source. The analysis of this scenario is best conducted from the frame of the receiver. Figure 3 shows the receiver being illuminated by light from when the source was closest to the receiver, even though the source has moved on. Because the source's clock is time dilated as measured in the frame of the receiver, and because there is no longitudinal component of its motion, the light from the source, emitted from this closest point, is redshifted with frequency

- Eq. 4:

In the literature, most reports of transverse Doppler shift analyze the effect in terms of the receiver pointed at direct right angles to the path of the source, thus seeing the source as being at its closest point and observing a redshift.

Point of null frequency shift

Given that, in the case where the inertially moving source and receiver are geometrically at their nearest approach to each other, the receiver observes a blueshift, whereas in the case where the receiver sees the source as being at its closest point, the receiver observes a redshift, there obviously must exist a point where blueshift changes to a redshift. In Fig. 2, the signal travels perpendicularly to the receiver path and is blueshifted. In Fig. 3, the signal travels perpendicularly to the source path and is redshifted.

As seen in Fig. 4, null frequency shift occurs for a pulse that travels the shortest distance from source to receiver. When viewed in the frame where source and receiver have the same speed, this pulse is emitted perpendicularly to the source's path and is received perpendicularly to the receiver's path. The pulse is emitted slightly before the point of closest approach, and it is received slightly after.

One object in circular motion around the other

Fig. 5 illustrates two variants of this scenario. Both variants can be analyzed using simple time dilation arguments. Figure 5a is essentially equivalent to the scenario described in Figure 2b, and the receiver observes light from the source as being blueshifted by a factor of . Figure 5b is essentially equivalent to the scenario described in Figure 3, and the light is redshifted.

The only seeming complication is that the orbiting objects are in accelerated motion. An accelerated particle does not have an inertial frame in which it is always at rest. However, an inertial frame can always be found which is momentarily comoving with the particle. This frame, the momentarily comoving reference frame (MCRF), enables application of special relativity to the analysis of accelerated particles. If an inertial observer looks at an accelerating clock, only the clock's instantaneous speed is important when computing time dilation.

The converse, however, is not true. The analysis of scenarios where both objects are in accelerated motion requires a somewhat more sophisticated analysis. Not understanding this point has led to confusion and misunderstanding.

Source and receiver both in circular motion around a common center

Suppose source and receiver are located on opposite ends of a spinning rotor, as illustrated in Fig. 6. Kinematic arguments (special relativity) and arguments based on noting that there is no difference in potential between source and receiver in the pseudogravitational field of the rotor (general relativity) both lead to the conclusion that there should be no Doppler shift between source and receiver.

In 1961, Champeney and Moon conducted a Mössbauer rotor experiment testing exactly this scenario, and found that the Mössbauer absorption process was unaffected by rotation. They concluded that their findings supported special relativity.

This conclusion generated some controversy. A certain persistent critic of relativity maintained that, although the experiment was consistent with general relativity, it refuted special relativity, his point being that since the emitter and absorber were in uniform relative motion, special relativity demanded that a Doppler shift be observed. The fallacy with this critic's argument was, as demonstrated in section Point of null frequency shift, that it is simply not true that a Doppler shift must always be observed between two frames in uniform relative motion. Furthermore, as demonstrated in section Source and receiver are at their points of closest approach, the difficulty of analyzing a relativistic scenario often depends on the choice of reference frame. Attempting to analyze the scenario in the frame of the receiver involves much tedious algebra. It is much easier, almost trivial, to establish the lack of Doppler shift between emitter and absorber in the laboratory frame.

As a matter of fact, however, Champeney and Moon's experiment said nothing either pro or con about special relativity. Because of the symmetry of the setup, it turns out that virtually any conceivable theory of the Doppler shift between frames in uniform inertial motion must yield a null result in this experiment.

Rather than being equidistant from the center, suppose the emitter and absorber were at differing distances from the rotor's center. For an emitter at radius and the absorber at radius anywhere on the rotor, the ratio of the emitter frequency, and the absorber frequency, is given by

- Eq. 5:

where is the angular velocity of the rotor. The source and emitter do not have to be 180° apart, but can be at any angle with respect to the center.

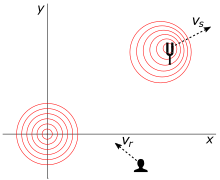

Motion in an arbitrary direction

The analysis used in section Relativistic longitudinal Doppler effect can be extended in a straightforward fashion to calculate the Doppler shift for the case where the inertial motions of the source and receiver are at any specified angle. Fig. 7 presents the scenario from the frame of the receiver, with the source moving at speed at an angle measured in the frame of the receiver. The radial component of the source's motion along the line of sight is equal to

The equation below can be interpreted as the classical Doppler shift for a stationary and moving source modified by the Lorentz factor

- Eq. 6:

In the case when , one obtains the transverse Doppler effect:

In his 1905 paper on special relativity, Einstein obtained a somewhat different looking equation for the Doppler shift equation. After changing the variable names in Einstein's equation to be consistent with those used here, his equation reads

- Eq. 7:

The differences stem from the fact that Einstein evaluated the angle with respect to the source rest frame rather than the receiver rest frame. is not equal to because of the effect of relativistic aberration. The relativistic aberration equation is:

- Eq. 8:

Substituting the relativistic aberration equation Equation 8 into Equation 6 yields Equation 7, demonstrating the consistency of these alternate equations for the Doppler shift.

Setting in Equation 6 or in Equation 7 yields Equation 1, the expression for relativistic longitudinal Doppler shift.

A four-vector approach to deriving these results may be found in Landau and Lifshitz (2005).

In electromagetic waves both the electric and the magnetic field amplitudes E and B transform in a similar manner as the frequency:

Visualization

Fig. 8 helps us understand, in a rough qualitative sense, how the relativistic Doppler effect and relativistic aberration differ from the non-relativistic Doppler effect and non-relativistic aberration of light. Assume that the observer is uniformly surrounded in all directions by yellow stars emitting monochromatic light of 570 nm. The arrows in each diagram represent the observer's velocity vector relative to its surroundings, with a magnitude of 0.89 c.

- In the relativistic case, the light ahead of the observer is blueshifted to a wavelength of 137 nm in the far ultraviolet, while light behind the observer is redshifted to 2400 nm in the short wavelength infrared. Because of the relativistic aberration of light, objects formerly at right angles to the observer appear shifted forwards by 63°.

- In the non-relativistic case, the light ahead of the observer is blueshifted to a wavelength of 300 nm in the medium ultraviolet, while light behind the observer is redshifted to 5200 nm in the intermediate infrared. Because of the aberration of light, objects formerly at right angles to the observer appear shifted forwards by 42°.

- In both cases, the monochromatic stars ahead of and behind the observer are Doppler-shifted towards invisible wavelengths. If, however, the observer had eyes that could see into the ultraviolet and infrared, he would see the stars ahead of him as brighter and more closely clustered together than the stars behind, but the stars would be far brighter and far more concentrated in the relativistic case.

Real stars are not monochromatic, but emit a range of wavelengths approximating a black body distribution. It is not necessarily true that stars ahead of the observer would show a bluer color. This is because the whole spectral energy distribution is shifted. At the same time that visible light is blueshifted into invisible ultraviolet wavelengths, infrared light is blueshifted into the visible range. Precisely what changes in the colors one sees depends on the physiology of the human eye and on the spectral characteristics of the light sources being observed.

Doppler effect on intensity

The Doppler effect (with arbitrary direction) also modifies the perceived source intensity: this can be expressed concisely by the fact that source strength divided by the cube of the frequency is a Lorentz invariant. This implies that the total radiant intensity (summing over all frequencies) is multiplied by the fourth power of the Doppler factor for frequency.

As a consequence, since Planck's law describes the black-body radiation as having a spectral intensity in frequency proportional to (where is the source temperature and the frequency), we can draw the conclusion that a black body spectrum seen through a Doppler shift (with arbitrary direction) is still a black body spectrum with a temperature multiplied by the same Doppler factor as frequency.

This result provides one of the pieces of evidence that serves to distinguish the Big Bang theory from alternative theories proposed to explain the cosmological redshift.

Experimental verification

Since the transverse Doppler effect is one of the main novel predictions of the special theory of relativity, the detection and precise quantification of this effect has been an important goal of experiments attempting to validate special relativity.

Ives and Stilwell-type measurements

Einstein (1907) had initially suggested that the TDE might be measured by observing a beam of "canal rays" at right angles to the beam. Attempts to measure TDE following this scheme proved it to be impractical, since the maximum speed of particle beam available at the time was only a few thousandths of the speed of light.

Fig. 9 shows the results of attempting to measure the 4861 Angstrom line emitted by a beam of canal rays (a mixture of H1+, H2+, and H3+ ions) as they recombine with electrons stripped from the dilute hydrogen gas used to fill the Canal ray tube. Here, the predicted result of the TDE is a 4861.06 Angstrom line. On the left, longitudinal Doppler shift results in broadening the emission line to such an extent that the TDE cannot be observed. The middle figures illustrate that even if one narrows one's view to the exact center of the beam, very small deviations of the beam from an exact right angle introduce shifts comparable to the predicted effect.

Rather than attempt direct measurement of the TDE, Ives and Stilwell (1938) used a concave mirror that allowed them to simultaneously observe a nearly longitudinal direct beam (blue) and its reflected image (red). Spectroscopically, three lines would be observed: An undisplaced emission line, and blueshifted and redshifted lines. The average of the redshifted and blueshifted lines would be compared with the wavelength of the undisplaced emission line. The difference that Ives and Stilwell measured corresponded, within experimental limits, to the effect predicted by special relativity.

Various of the subsequent repetitions of the Ives and Stilwell experiment have adopted other strategies for measuring the mean of blueshifted and redshifted particle beam emissions. In some recent repetitions of the experiment, modern accelerator technology has been used to arrange for the observation of two counter-rotating particle beams. In other repetitions, the energies of gamma rays emitted by a rapidly moving particle beam have been measured at opposite angles relative to the direction of the particle beam. Since these experiments do not actually measure the wavelength of the particle beam at right angles to the beam, some authors have preferred to refer to the effect they are measuring as the "quadratic Doppler shift" rather than TDE.

Direct measurement of transverse Doppler effect

The advent of particle accelerator technology has made possible the production of particle beams of considerably higher energy than was available to Ives and Stilwell. This has enabled the design of tests of the transverse Doppler effect directly along the lines of how Einstein originally envisioned them, i.e. by directly viewing a particle beam at a 90° angle. For example, Hasselkamp et al. (1979) observed the Hα line emitted by hydrogen atoms moving at speeds ranging from 2.53×108 cm/s to 9.28×108 cm/s, finding the coefficient of the second order term in the relativistic approximation to be 0.52±0.03, in excellent agreement with the theoretical value of 1/2.

Other direct tests of the TDE on rotating platforms were made possible by the discovery of the Mössbauer effect, which enables the production of exceedingly narrow resonance lines for nuclear gamma ray emission and absorption. Mössbauer effect experiments have proven themselves easily capable of detecting TDE using emitter-absorber relative velocities on the order of 2×104 cm/s. These experiments include ones performed by Hay et al. (1960), Champeney et al. (1965), and Kündig (1963).

Time dilation measurements

The transverse Doppler effect and the kinematic time dilation of special relativity are closely related. All validations of TDE represent validations of kinematic time dilation, and most validations of kinematic time dilation have also represented validations of TDE. An online resource, "What is the experimental basis of Special Relativity?" has documented, with brief commentary, many of the tests that, over the years, have been used to validate various aspects of special relativity. Kaivola et al. (1985) and McGowan et al. (1993) are examples of experiments classified in this resource as time dilation experiments. These two also represent tests of TDE. These experiments compared the frequency of two lasers, one locked to the frequency of a neon atom transition in a fast beam, the other locked to the same transition in thermal neon. The 1993 version of the experiment verified time dilation, and hence TDE, to an accuracy of 2.3×10−6.

Relativistic Doppler effect for sound and light

First-year physics textbooks almost invariably analyze Doppler shift for sound in terms of Newtonian kinematics, while analyzing Doppler shift for light and electromagnetic phenomena in terms of relativistic kinematics. This gives the false impression that acoustic phenomena requires a different analysis than light and radio waves.

The traditional analysis of the Doppler effect for sound represents a low speed approximation to the exact, relativistic analysis. The fully relativistic analysis for sound is, in fact, equally applicable to both sound and electromagnetic phenomena.

Consider the spacetime diagram in Fig. 10. Worldlines for a tuning fork (the source) and a receiver are both illustrated on this diagram. The tuning fork and receiver start at O, at which point the tuning fork starts to vibrate, emitting waves and moving along the negative x-axis while the receiver starts to move along the positive x-axis. The tuning fork continues until it reaches A, at which point it stops emitting waves: a wavepacket has therefore been generated, and all the waves in the wavepacket are received by the receiver with the last wave reaching it at B. The proper time for the duration of the packet in the tuning fork's frame of reference is the length of OA while the proper time for the duration of the wavepacket in the receiver's frame of reference is the length of OB. If waves were emitted, then , while ; the inverse slope of AB represents the speed of signal propagation (i.e. the speed of sound) to event B. We can therefore write:

- (speed of sound)

- (speeds of source and receiver)

and are assumed to be less than since otherwise their passage through the medium will set up shock waves, invalidating the calculation. Routine algebra gives the ratio of frequencies:

- Eq. 9:

If and are small compared with , the above equation reduces to the classical Doppler formula for sound.

If the speed of signal propagation approaches , it can be shown that the absolute speeds and of the source and receiver merge into a single relative speed independent of any reference to a fixed medium. Indeed, we obtain Equation 1, the formula for relativistic longitudinal Doppler shift.

Analysis of the spacetime diagram in Fig. 10 gave a general formula for source and receiver moving directly along their line of sight, i.e. in collinear motion.

Fig. 11 illustrates a scenario in two dimensions. The source moves with velocity (at the time of emission). It emits a signal which travels at velocity towards the receiver, which is traveling at velocity at the time of reception. The analysis is performed in a coordinate system in which the signal's speed is independent of direction.

The ratio between the proper frequencies for the source and receiver is

- Eq. 10:

The leading ratio has the form of the classical Doppler effect, while the square root term represents the relativistic correction. If we consider the angles relative to the frame of the source, then and the equation reduces to Equation 7, Einstein's 1905 formula for the Doppler effect. If we consider the angles relative to the frame of the receiver, then and the equation reduces to Equation 6, the alternative form of the Doppler shift equation discussed previously.