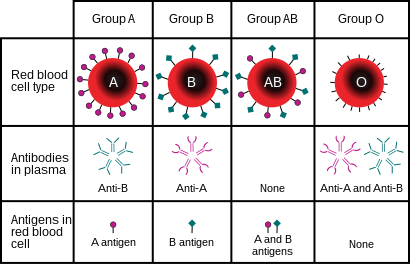

The ABO blood group system is used to denote the presence of one, both, or neither of the A and B antigens on erythrocytes. For human blood transfusions, it is the most important of the 44 different blood type (or group) classification systems currently recognized by the International Society of Blood Transfusions (ISBT) as of December 2022. A mismatch (very rare in modern medicine) in this, or any other serotype, can cause a potentially fatal adverse reaction after a transfusion, or an unwanted immune response to an organ transplant. The associated anti-A and anti-B antibodies are usually IgM antibodies, produced in the first years of life by sensitization to environmental substances such as food, bacteria, and viruses.

The ABO blood types were discovered by Karl Landsteiner in 1901; he received the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1930 for this discovery. ABO blood types are also present in other primates such as apes and Old World monkeys.

History

Discovery

The ABO blood types were first discovered by an Austrian physician, Karl Landsteiner, working at the Pathological-Anatomical Institute of the University of Vienna (now Medical University of Vienna). In 1900, he found that red blood cells would clump together (agglutinate) when mixed in test tubes with sera from different persons, and that some human blood also agglutinated with animal blood. He wrote a two-sentence footnote:

The serum of healthy human beings not only agglutinates animal red cells, but also often those of human origin, from other individuals. It remains to be seen whether this appearance is related to inborn differences between individuals or it is the result of some damage of bacterial kind.

This was the first evidence that blood variations exist in humans – it was believed that all humans have similar blood. The next year, in 1901, he made a definitive observation that blood serum of an individual would agglutinate with only those of certain individuals. Based on this he classified human blood into three groups, namely group A, group B, and group C. He defined that group A blood agglutinates with group B, but never with its own type. Similarly, group B blood agglutinates with group A. Group C blood is different in that it agglutinates with both A and B.

This was the discovery of blood groups for which Landsteiner was awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 1930. In his paper, he referred to the specific blood group interactions as isoagglutination, and also introduced the concept of agglutinins (antibodies), which is the actual basis of antigen-antibody reaction in the ABO system. He asserted:

[It] may be said that there exist at least two different types of agglutinins, one in A, another one in B, and both together in C. The red blood cells are inert to the agglutinins which are present in the same serum.

Thus, he discovered two antigens (agglutinogens A and B) and two antibodies (agglutinins – anti-A and anti-B). His third group (C) indicated absence of both A and B antigens, but contains anti-A and anti-B. The following year, his students Adriano Sturli and Alfred von Decastello discovered the fourth type (but not naming it, and simply referred to it as "no particular type").

In 1910, Ludwik Hirszfeld and Emil Freiherr von Dungern introduced the term 0 (null) for the group Landsteiner designated as C, and AB for the type discovered by Sturli and von Decastello. They were also the first to explain the genetic inheritance of the blood groups.

Classification systems

Czech serologist Jan Janský independently introduced blood type classification in 1907 in a local journal. He used the Roman numerical I, II, III, and IV (corresponding to modern O, A, B, and AB). Unknown to Janský, an American physician William L. Moss devised a slightly different classification using the same numerical; his I, II, III, and IV corresponding to modern AB, A, B, and O.

These two systems created confusion and potential danger in medical practice. Moss's system was adopted in Britain, France, and US, while Janský's was preferred in most European countries and some parts of US. To resolve the chaos, the American Association of Immunologists, the Society of American Bacteriologists, and the Association of Pathologists and Bacteriologists made a joint recommendation in 1921 that the Jansky classification be adopted based on priority. But it was not followed particularly where Moss's system had been used.

In 1927, Landsteiner had moved to the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research in New York. As a member of a committee of the National Research Council concerned with blood grouping, he suggested to substitute Janský's and Moss's systems with the letters O, A, B, and AB. (There was another confusion on the use of figure 0 for German null as introduced by Hirszfeld and von Dungern, because others used the letter O for ohne, meaning without or zero; Landsteiner chose the latter.) This classification was adopted by the National Research Council and became variously known as the National Research Council classification, the International classification, and most popularly the "new" Landsteiner classification. The new system was gradually accepted and by the early 1950s, it was universally followed.

Other developments

The first practical use of blood typing in transfusion was by an American physician Reuben Ottenberg in 1907. Large-scale application began during the First World War (1914–1915) when citric acid began to be used for blood clot prevention. Felix Bernstein demonstrated the correct blood group inheritance pattern of multiple alleles at one locus in 1924. Watkins and Morgan, in England, discovered that the ABO epitopes were conferred by sugars, to be specific, N-acetylgalactosamine for the A-type and galactose for the B-type. After much published literature claiming that the ABH substances were all attached to glycosphingolipids, Finne et al. (1978) found that the human erythrocyte glycoproteins contain polylactosamine chains that contains ABH substances attached and represent the majority of the antigens. The main glycoproteins carrying the ABH antigens were identified to be the Band 3 and Band 4.5 proteins and glycophorin. Later, Yamamoto's group showed the precise glycosyl transferase set that confers the A, B and O epitopes.

-

Diagram showing the carbohydrate chains that determine the ABO blood group

-

Student blood test. Three drops of blood are mixed with anti-B (left) and anti-A (right) serum. Agglutination with anti-A suggests this individual is type A.

-

There are three basic variants of immunoglobulin antigens in humans that share a very similar chemical structure but are distinctly different. Red circles show where there are differences in chemical structure in the antigen-binding site (sometimes called the antibody-combining site) of human immunoglobulin. Notice the O-type antigen does not have a binding site.

Genetics

Blood groups are inherited from both parents. The ABO blood type is controlled by a single gene (the ABO gene) with three types of alleles inferred from classical genetics: i, IA, and IB. The I designation stands for isoagglutinogen, another term for antigen. The gene encodes a glycosyltransferase—that is, an enzyme that modifies the carbohydrate content of the red blood cell antigens. The gene is located on the long arm of the ninth chromosome (9q34).

The IA allele gives type A, IB gives type B, and i gives type O. As both IA and IB are dominant over i, only ii people have type O blood. Individuals with IAIA or IAi have type A blood, and individuals with IBIB or IBi have type B. IAIB people have both phenotypes, because A and B express a special dominance relationship: codominance, which means that type A and B parents can have an AB child. A couple with type A and type B can also have a type O child if they are both heterozygous (IBi and IAi). The cis-AB phenotype has a single enzyme that creates both A and B antigens. The resulting red blood cells do not usually express A or B antigen at the same level that would be expected on common group A1 or B red blood cells, which can help solve the problem of an apparently genetically impossible blood group.

| Blood group inheritance | |||||||

| Blood type |

|

O | A | B | AB | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

Genotype | ii (OO) | IAi (AO) | IAIA (AA) | IBi (BO) | IBIB (BB) | IAIB (AB) |

| O | ii (OO) | O OO OO OO OO |

O or A AO OO AO OO |

A AO AO AO AO |

O or B BO OO BO OO |

B BO BO BO BO |

A or B AO BO AO BO |

| A | IAi (AO) | O or A AO AO OO OO |

O or A AA AO AO OO |

A AA AA AO AO |

O, A, B or AB AB AO BO OO |

B or AB AB AB BO BO |

A, B or AB AA AB AO BO |

| IAIA (AA) | A AO AO AO AO |

A AA AO AA AO |

A AA AA AA AA |

A or AB AB AO AB AO |

AB AB AB AB AB |

A or AB AA AB AA AB | |

| B | IBi (BO) | O or B BO BO OO OO |

O, A, B or AB AB BO AO OO |

A or AB AB AB AO AO |

O or B BB BO BO OO |

B BB BB BO BO |

A, B or AB AB BB AO BO |

| IBIB (BB) | B BO BO BO BO |

B or AB AB BO AB BO |

AB AB AB AB AB |

B BB BO BB BO |

B BB BB BB BB |

B or AB AB BB AB BB | |

| AB | IAIB (AB) | A or B AO AO BO BO |

A, B or AB AA AO AB BO |

A or AB AA AA AB AB |

A, B or AB AB AO BB BO |

B or AB AB AB BB BB |

A, B, or AB AA AB AB BB |

The table above summarizes the various blood groups that children may inherit from their parents. Genotypes are shown in the second column and in small print for the offspring: AO and AA both test as type A; BO and BB test as type B. The four possibilities represent the combinations obtained when one allele is taken from each parent; each has a 25% chance, but some occur more than once. The text above them summarizes the outcomes.

| Blood group inheritance by phenotype only | ||||

| Blood type | O | A | B | AB |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| O | O | O or A | O or B | A or B |

| A | O or A | O or A | O, A, B or AB | A, B or AB |

| B | O or B | O, A, B or AB | O or B | A, B or AB |

| AB | A or B | A, B or AB | A, B or AB | A, B or AB |

Historically, ABO blood tests were used in paternity testing, but in 1957 only 50% of American men falsely accused were able to use them as evidence against paternity. Occasionally, the blood types of children are not consistent with expectations—for example, a type O child can be born to an AB parent—due to rare situations, such as Bombay phenotype and cis AB.

Subgroups

The A blood type contains about 20 subgroups, of which A1 and A2 are the most common (over 99%). A1 makes up about 80% of all A-type blood, with A2 making up almost all of the rest. These two subgroups are not always interchangeable as far as transfusion is concerned, as some A2 individuals produce antibodies against the A1 antigen. Complications can sometimes arise in rare cases when typing the blood.

With the development of DNA sequencing, it has been possible to identify a much larger number of alleles at the ABO locus, each of which can be categorized as A, B, or O in terms of the reaction to transfusion, but which can be distinguished by variations in the DNA sequence. There are six common alleles in white individuals of the ABO gene that produce one's blood type:

| A | B | O |

|---|---|---|

| A101 (A1) A201 (A2) |

B101 (B1) | O01 (O1) O02 (O1v) O03 (O2) |

The same study also identified 18 rare alleles, which generally have a weaker glycosylation activity. People with weak alleles of A can sometimes express anti-A antibodies, though these are usually not clinically significant as they do not stably interact with the antigen at body temperature.

Cis AB is another rare variant, in which A and B genes are transmitted together from a single parent.

Distribution and evolutionary history

The distribution of the blood groups A, B, O and AB varies across the world according to the population. There are also variations in blood type distribution within human subpopulations.

In the UK, the distribution of blood type frequencies through the population still shows some correlation to the distribution of placenames and to the successive invasions and migrations including Celts, Norsemen, Danes, Anglo-Saxons, and Normans who contributed the morphemes to the placenames and the genes to the population. The native Celts tended to have more type O blood, while the other populations tended to have more type A.

The two common O alleles, O01 and O02, share their first 261 nucleotides with the group A allele A01. However, unlike the group A allele, a guanosine base is subsequently deleted. A premature stop codon results from this frame-shift mutation. This variant is found worldwide, and likely predates human migration from Africa. The O01 allele is considered to predate the O02 allele.

Some evolutionary biologists theorize that there are four main lineages of the ABO gene and that mutations creating type O have occurred at least three times in humans. From oldest to youngest, these lineages comprise the following alleles: A101/A201/O09, B101, O02 and O01. The continued presence of the O alleles is hypothesized to be the result of balancing selection. Both theories contradict the previously held theory that type O blood evolved first.

Origin theories

It is possible that food and environmental antigens (bacterial, viral, or plant antigens) have epitopes similar enough to A and B glycoprotein antigens. The antibodies created against these environmental antigens in the first years of life can cross-react with ABO-incompatible red blood cells that it comes in contact with during blood transfusion later in life. Anti-A antibodies are hypothesized to originate from immune response towards influenza virus, whose epitopes are similar enough to the α-D-N-galactosamine on the A glycoprotein to be able to elicit a cross-reaction. Anti-B antibodies are hypothesized to originate from antibodies produced against Gram-negative bacteria, such as E. coli, cross-reacting with the α-D-galactose on the B glycoprotein.

However, it is more likely that the force driving evolution of allele diversity is simply negative frequency-dependent selection; cells with rare variants of membrane antigens are more easily distinguished by the immune system from pathogens carrying antigens from other hosts. Thus, individuals possessing rare types are better equipped to detect pathogens. The high within-population diversity observed in human populations would, then, be a consequence of natural selection on individuals.

Clinical relevance

The carbohydrate molecules on the surfaces of red blood cells have roles in cell membrane integrity, cell adhesion, membrane transportation of molecules, and acting as receptors for extracellular ligands, and enzymes. ABO antigens are found having similar roles on epithelial cells as well as red blood cells.

Bleeding and thrombosis (von Willebrand factor)

The ABO antigen is also expressed on the von Willebrand factor (vWF) glycoprotein, which participates in hemostasis (control of bleeding). In fact, having type O blood predisposes to bleeding, as 30% of the total genetic variation observed in plasma vWF is explained by the effect of the ABO blood group, and individuals with group O blood normally have significantly lower plasma levels of vWF (and Factor VIII) than do non-O individuals. In addition, vWF is degraded more rapidly due to the higher prevalence of blood group O with the Cys1584 variant of vWF (an amino acid polymorphism in VWF): the gene for ADAMTS13 (vWF-cleaving protease) maps to human chromosome 9 band q34.2, the same locus as ABO blood type. Higher levels of vWF are more common amongst people who have had ischemic stroke (from blood clotting) for the first time. The results of this study found that the occurrence was not affected by ADAMTS13 polymorphism, and the only significant genetic factor was the person's blood group.

ABO hemolytic disease of the newborn

ABO blood group incompatibilities between the mother and child do not usually cause hemolytic disease of the newborn (HDN) because antibodies to the ABO blood groups are usually of the IgM type, which do not cross the placenta. However, in an O-type mother, IgG ABO antibodies are produced and the baby can potentially develop ABO hemolytic disease of the newborn.

Clinical applications

In human cells, the ABO alleles and their encoded glycosyltransferases have been described in several oncologic conditions. Using anti-GTA/GTB monoclonal antibodies, it was demonstrated that a loss of these enzymes was correlated to malignant bladder and oral epithelia. Furthermore, the expression of ABO blood group antigens in normal human tissues is dependent the type of differentiation of the epithelium. In most human carcinomas, including oral carcinoma, a significant event as part of the underlying mechanism is decreased expression of the A and B antigens. Several studies have observed that a relative down-regulation of GTA and GTB occurs in oral carcinomas in association with tumor development. More recently, a genome wide association study (GWAS) has identified variants in the ABO locus associated with susceptibility to pancreatic cancer. In addition, another large GWAS study has associated ABO-histo blood groups as well as FUT2 secretor status with the presence in the intestinal microbiome of specific bacterial species. In this case the association was with Bacteroides and Faecalibacterium spp. Bacteroides of the same OTU (operational taxonomic unit) have been shown to be associated with inflammatory bowel disease, thus the study suggests an important role for the ABO histo-blood group antigens as candidates for direct modulation of the human microbiome in health and disease.

Clinical marker

A multi-locus genetic risk score study based on a combination of 27 loci, including the ABO gene, identified individuals at increased risk for both incident and recurrent coronary artery disease events, as well as an enhanced clinical benefit from statin therapy. The study was based on a community cohort study (the Malmo Diet and Cancer study) and four additional randomized controlled trials of primary prevention cohorts (JUPITER and ASCOT) and secondary prevention cohorts (CARE and PROVE IT-TIMI 22).

Alteration of ABO antigens for transfusion

In April 2007, an international team of researchers announced in the journal Nature Biotechnology an inexpensive and efficient way to convert types A, B, and AB blood into type O. This is done by using glycosidase enzymes from specific bacteria to strip the blood group antigens from red blood cells. The removal of A and B antigens still does not address the problem of the Rh blood group antigen on the blood cells of Rh positive individuals, and so blood from Rh negative donors must be used. The modified blood is named "enzyme converted to O" (ECO blood) but despite the early success of converting B- to O-type RBCs and clinical trials without adverse effects transfusing into A- and O-type patients, the technology has not yet become clinical practice.

Another approach to the blood antigen problem is the manufacture of artificial blood, which could act as a substitute in emergencies.

Pseudoscience

During the 1930s, connecting blood groups to personality types became popular in Japan and other areas of the world. Studies of this association have yet to confirm its existence definitively.

Other popular but unsupported ideas include the use of a blood type diet, claims that group A causes severe hangovers, group O is associated with perfect teeth, and those with blood group A2 have the highest IQs. Scientific evidence in support of these concepts is limited at best.

![There are three basic variants of immunoglobulin antigens in humans that share a very similar chemical structure but are distinctly different. Red circles show where there are differences in chemical structure in the antigen-binding site (sometimes called the antibody-combining site) of human immunoglobulin. Notice the O-type antigen does not have a binding site.[30]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/aa/AP-Biology_Final_Project.svg/147px-AP-Biology_Final_Project.svg.png)