In mathematics, division by zero is division where the divisor (denominator) is zero. Such a division can be formally expressed as , where a is the dividend (numerator). In ordinary arithmetic, the expression has no meaning, as there is no number that, when multiplied by 0, gives a (assuming ); thus, division by zero is undefined (a type of singularity). Since any number multiplied by zero is zero, the expression is also undefined; when it is the form of a limit, it is an indeterminate form. Historically, one of the earliest recorded references to the mathematical impossibility of assigning a value to is contained in Anglo-Irish philosopher George Berkeley's criticism of infinitesimal calculus in 1734 in The Analyst ("ghosts of departed quantities").

There are mathematical structures in which is defined for some a such as in the Riemann sphere (a model of the extended complex plane) and the projectively extended real line; however, such structures do not satisfy every ordinary rule of arithmetic (the field axioms).

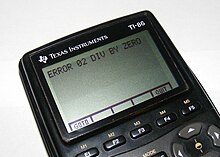

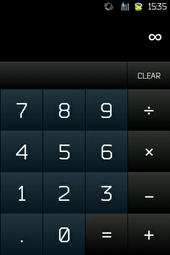

In computing, a program error may result from an attempt to divide by zero. Depending on the programming environment and the type of number (e.g., floating point, integer) being divided by zero, it may generate positive or negative infinity by the IEEE 754 floating-point standard, generate an exception, generate an error message, cause the program to terminate, result in a special not-a-number value, or crash.

Elementary arithmetic

When division is explained at the elementary arithmetic level, it is often considered as splitting a set of objects into equal parts. As an example, consider having ten cookies, and these cookies are to be distributed equally to five people at a table. Each person would receive cookies. Similarly, if there are ten cookies, and only one person at the table, that person would receive cookies.

So, for dividing by zero, what is the number of cookies that each person receives when 10 cookies are evenly distributed among 0 people at a table? Certain words can be pinpointed in the question to highlight the problem. The problem with this question is the "when". There is no way to distribute 10 cookies to nobody. Therefore, —at least in elementary arithmetic—is said to be either meaningless or undefined.

If there are 5 cookies and 2 people, the problem is in "evenly distribute". In any integer partition of 5 things into 2 parts, either one of the parts of the partition will have more elements than the other or there will be a remainder (written as 5/2 = 2 r1). Or, the problem with 5 cookies and 2 people can be solved by cutting one cookie in half, which introduces the idea of fractions (5/2 = 2+1/2) . The problem with 5 cookies and 0 people, on the other hand, cannot be solved in any way that preserves the meaning of "divides".

In elementary algebra, another way of looking at division by zero is that division can always be checked using multiplication. Considering the 10/0 example above, setting x = 10/0, if x equals ten divided by zero, then x times zero equals ten, but there is no x that, when multiplied by zero, gives ten (or any number other than zero). If, instead of x = 10/0, x = 0/0, then every x satisfies the question "what number x, multiplied by zero, gives zero?"

Early attempts

The Brāhmasphuṭasiddhānta of Brahmagupta (c. 598–668) is the earliest text to treat zero as a number in its own right and to define operations involving zero. The author could not explain division by zero in his texts: his definition can be easily proven to lead to algebraic absurdities. According to Brahmagupta,

A positive or negative number when divided by zero is a fraction with the zero as denominator. Zero divided by a negative or positive number is either zero or is expressed as a fraction with zero as numerator and the finite quantity as denominator. Zero divided by zero is zero.

In 830, Mahāvīra unsuccessfully tried to correct the mistake Brahmagupta made in his book Ganita Sara Samgraha: "A number remains unchanged when divided by zero."

Algebra

The four basic operations – addition, subtraction, multiplication and division – as applied to whole numbers (positive integers), with some restrictions, in elementary arithmetic are used as a framework to support the extension of the realm of numbers to which they apply. For instance, to make it possible to subtract any whole number from another, the realm of numbers must be expanded to the entire set of integers in order to incorporate the negative integers. Similarly, to support division of any integer by any other, the realm of numbers must expand to the rational numbers. During this gradual expansion of the number system, care is taken to ensure that the "extended operations", when applied to the older numbers, do not produce different results. Loosely speaking, since division by zero has no meaning (is undefined) in the whole number setting, this remains true as the setting expands to the real or even complex numbers.

As the realm of numbers to which these operations can be applied expands there are also changes in how the operations are viewed. For instance, in the realm of integers, subtraction is no longer considered a basic operation since it can be replaced by addition of signed numbers. Similarly, when the realm of numbers expands to include the rational numbers, division is replaced by multiplication by certain rational numbers. In keeping with this change of viewpoint, the question, "Why can't we divide by zero?", becomes "Why can't a rational number have a zero denominator?". Answering this revised question precisely requires close examination of the definition of rational numbers.

In the modern approach to constructing the field of real numbers, the rational numbers appear as an intermediate step in the development that is founded on set theory. First, the natural numbers (including zero) are established on an axiomatic basis such as Peano's axiom system and then this is expanded to the ring of integers. The next step is to define the rational numbers keeping in mind that this must be done using only the sets and operations that have already been established, namely, addition, multiplication and the integers. Starting with the set of ordered pairs of integers, {(a, b)} with b ≠ 0, define a binary relation on this set by (a, b) ≃ (c, d) if and only if ad = bc. This relation is shown to be an equivalence relation and its equivalence classes are then defined to be the rational numbers. It is in the formal proof that this relation is an equivalence relation that the requirement that the second coordinate is not zero is needed (for verifying transitivity).

The above explanation may be too abstract and technical for many purposes, but if one assumes the existence and properties of the rational numbers, as is commonly done in elementary mathematics, the "reason" that division by zero is not allowed is hidden from view. Nevertheless, a (non-rigorous) justification can be given in this setting.

It follows from the properties of the number system we commonly use that if b ≠ 0, then the equation a/b = c is equivalent to a = b × c. If we allowed a zero denominator, we would arrive at either a contradiction, or an equation that was true no matter what value we assigned the "fraction". If a/0 were a number c, then it would follow that a = 0 × c = 0. However, the single number c would then have to be determined by the equation 0 = 0 × c, which is satisfied by every number. We cannot assign a numerical value to 0/0 and instead say that division by zero is not allowed.

Division as the inverse of multiplication

The concept that explains division in algebra is that it is the inverse of multiplication. For example,

The expression

In general, a single value can't be assigned to a fraction where the denominator is 0 so the value remains undefined.

Fallacies

A compelling reason for not allowing division by zero is that, if it were allowed, many absurd results (i.e., fallacies) would arise. When working with numerical quantities it is easy to determine when an illegal attempt to divide by zero is being made. For example, consider the following computation.

With the assumptions:

Dividing both sides by zero gives:

Simplified, this yields:

However, it is possible to disguise a division by zero in an algebraic argument, leading to invalid proofs that, for instance, 1 = 2 such as the following:

Multiply by x to get

The disguised division by zero occurs since x − 1 = 0 when x = 1.

Analysis

Extended real line

At first glance it seems possible to define a/0 by considering the limit of a/b as b approaches 0.

For any positive a, the limit from the right is

and so the is undefined (the limit is also undefined for negative a).

Furthermore, there is no obvious definition of 0/0 that can be derived from considering the limit of a ratio. The limit

For example, consider:

This initially appears to be indeterminate. However:

and so the limit exists, and is equal to .

These and other similar facts show that the expression cannot be well-defined as a limit.

Formal operations

A formal calculation is one carried out using rules of arithmetic, without consideration of whether the result of the calculation is well-defined. Thus, it is sometimes useful to think of a/0, where a ≠ 0, as being . This infinity can be either positive, negative, or unsigned, depending on context. For example, formally:

As with any formal calculation, invalid results may be obtained. A logically rigorous (as opposed to formal) computation would assert only that

Since the one-sided limits are different, the two-sided limit does not exist in the standard framework of the real numbers. Also, the fraction 1/0 is left undefined in the extended real line, therefore it and

are meaningless expressions.

Projectively extended real line

The set is the projectively extended real line, which is a one-point compactification of the real line. Here means an unsigned infinity or point at infinity, an infinite quantity that is neither positive nor negative. This quantity satisfies , which is necessary in this context. In this structure, can be defined for nonzero a, and when a is not . It is the natural way to view the range of the tangent function and cotangent functions of trigonometry: tan(x) approaches the single point at infinity as x approaches either +π/2 or −π/2 from either direction.

This definition leads to many interesting results. However, the resulting algebraic structure is not a field, and should not be expected to behave like one. For example, is undefined in this extension of the real line.

Riemann sphere

The set is the Riemann sphere, which is of major importance in complex analysis. Here represents complex infinity, which is also a point at infinity. This set is analogous to the projectively extended real line, except that it is based on the field of complex numbers. In the Riemann sphere, and , but , , and are undefined.

Higher mathematics

Although division by zero cannot be sensibly defined with real numbers and integers, it is possible to consistently define it, or similar operations, in other mathematical structures.

Non-standard analysis

In the hyperreal numbers and the surreal numbers, division by zero is still impossible, but division by non-zero infinitesimals is possible.

Distribution theory

In distribution theory one can extend the function to a distribution on the whole space of real numbers (in effect by using Cauchy principal values). It does not, however, make sense to ask for a "value" of this distribution at x = 0; a sophisticated answer refers to the singular support of the distribution.

Linear algebra

In matrix algebra (or linear algebra in general), one can define a pseudo-division, by setting a/b = ab+, in which b+ represents the pseudoinverse of b. It can be proven that if b−1 exists, then b+ = b−1. If b equals 0, then b+ = 0.

Abstract algebra

In abstract algebra, the integers, the rational numbers, the real numbers, and the complex numbers can be abstracted to more general algebraic structures, such as a commutative ring, which is a mathematical structure where addition, subtraction, and multiplication behave as they do in the more familiar number systems, but division may not be defined. Adjoining a multiplicative inverses to a commutative ring is called localization. However, the localization of every commutative ring at zero is the trivial ring, where , so nontrivial commutative rings do not have inverses at zero, and thus division by zero is undefined for nontrivial commutative rings.

Nevertheless, any number system that forms a commutative ring can be extended to a seldom used structure called a wheel in which division by zero is always possible. However, the resulting mathematical structure is no longer a commutative ring, as multiplication no longer distributes over addition. Furthermore, in a wheel, division of an element by itself no longer results in the multiplicative identity element , and if the original system was an integral domain, the multiplication in the wheel no longer results in a cancellative semigroup.

The concepts applied to standard arithmetic are similar to those in more general algebraic structures, such as rings and fields. In a field, every nonzero element is invertible under multiplication; as above, division poses problems only when attempting to divide by zero. This is likewise true in a skew field (which for this reason is called a division ring). However, in other rings, division by nonzero elements may also pose problems. For example, the ring Z/6Z of integers mod 6. The meaning of the expression should be the solution x of the equation . But in the ring Z/6Z, 2 is a zero divisor. This equation has two distinct solutions, x = 1 and x = 4, so the expression is undefined.

In field theory, the expression is only shorthand for the formal expression ab−1, where b−1 is the multiplicative inverse of b. Since the field axioms only guarantee the existence of such inverses for nonzero elements, this expression has no meaning when b is zero. Modern texts, that define fields as a special type of ring, include the axiom 0 ≠ 1 for fields (or its equivalent) so that the zero ring is excluded from being a field. In the zero ring, division by zero is possible, which shows that the other field axioms are not sufficient to exclude division by zero in a field.

Computer arithmetic

The IEEE floating-point standard, supported by almost all modern floating-point units, specifies that every floating-point arithmetic operation, including division by zero, has a well-defined result. The standard supports signed zero, as well as infinity and NaN (not a number). There are two zeroes: +0 (positive zero) and −0 (negative zero) and this removes any ambiguity when dividing. In IEEE 754 arithmetic, a ÷ +0 is positive infinity when a is positive, negative infinity when a is negative, and NaN when a = ±0. The infinity signs change when dividing by −0 instead.

The justification for this definition is to preserve the sign of the result in case of arithmetic underflow. For example, in the single-precision computation 1/(x/2), where x = ±2−149, the computation x/2 underflows and produces ±0 with sign matching x, and the result will be ±∞ with sign matching x. The sign will match that of the exact result ±2150, but the magnitude of the exact result is too large to represent, so infinity is used to indicate overflow.

Integer division by zero is usually handled differently from floating point since there is no integer representation for the result. Some processors generate an exception when an attempt is made to divide an integer by zero, although others will simply continue and generate an incorrect result for the division. The result depends on how division is implemented, and can either be zero, or sometimes the largest possible integer.

Because of the improper algebraic results of assigning any value to division by zero, many computer programming languages (including those used by calculators) explicitly forbid the execution of the operation and may prematurely halt a program that attempts it, sometimes reporting a "Divide by zero" error. In these cases, if some special behavior is desired for division by zero, the condition must be explicitly tested (for example, using an if statement). Some programs (especially those that use fixed-point arithmetic where no dedicated floating-point hardware is available) will use behavior similar to the IEEE standard, using large positive and negative numbers to approximate infinities. In some programming languages, an attempt to divide by zero results in undefined behavior. The graphical programming language Scratch 2.0 and 3.0 used in many schools returns Infinity or −Infinity depending on the sign of the dividend.

In two's complement arithmetic, attempts to divide the smallest signed integer by −1 are attended by similar problems, and are handled with the same range of solutions, from explicit error conditions to undefined behavior.

Most calculators will either return an error or state that 1/0 is undefined; however, some TI and HP graphing calculators will evaluate (1/0)2 to ∞.

Microsoft Math Solver and Wolfram Mathematica return ComplexInfinity for 1/0. Maple and SageMath

return an error message for 1/0, and infinity for 1/0.0 (0.0 tells

these systems to use floating-point arithmetic instead of algebraic

arithmetic).

Some modern calculators allow division by zero in special cases, where it will be useful to students and, presumably, understood in context by mathematicians. Some calculators, the online Desmos calculator is one example, allow arctangent(1/0). Students are often taught that the inverse cotangent function, arccotangent, should be calculated by taking the arctangent of the reciprocal, and so a calculator may allow arctangent(1/0), giving the output , which is the correct value of arccotangent 0. The mathematical justification is that the limit as x goes to zero of arctangent 1/x is .

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{\frac {0\times 1}{0}}&={\frac {0\times 2}{0}}\\[6px]{\frac {0}{0}}\times 1&={\frac {0}{0}}\times 2.\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/963d562d57c37899b76e2b4c1d466f14fe56c5ce)

![{\displaystyle {\begin{aligned}{\frac {x-1}{x-1}}&={\frac {x^{2}-1}{x-1}}\\[6pt]&={\frac {(x+1)(x-1)}{x-1}},\end{aligned}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fb9d61ae4a945903bdeaf18a331b7fa20ad8242d)