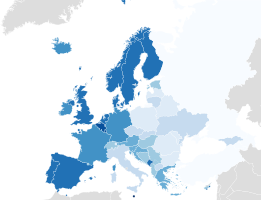

LGBT rights in Europe | |

|---|---|

Same-sex marriage

Civil unions

Limited domestic recognition (cohabitation)

Limited foreign recognition (residency rights)

No recognition

Constitutional limit on marriage | |

| Status | Legal, with an equal age of consent, in all 51 states Legal, with an equal age of consent, in all 6 dependencies and other territories |

| Gender identity | Legal in 39 out of 51 states Legal in 3 out of 6 dependencies and other territories |

| Military | Allowed to serve openly in 40 out of 47 states having an army Allowed in all 6 dependencies and other territories |

| Discrimination protections | Protected in 44 out of 51 states Protected in all 6 dependencies and other territories |

| Family rights | |

| Recognition of relationships | Recognised in 29 out of 51 states Recognised in all 6 dependencies and other territories |

| Restrictions | Same-sex marriage constitutionally banned in 15 out of 51 states |

| Adoption | Legal in 22 out of 51 states Legal in 5 out of 6 dependencies and other territories |

Lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) rights are widely diverse in Europe per country. Twenty of the 35 countries that have legalised same-sex marriage worldwide are situated in Europe. A further eleven European countries have legalised civil unions or other forms of more limited recognition for same-sex couples.

Several European countries do not recognise any form of same-sex unions. Marriage is defined as a union solely between a man and a woman in the constitutions of Armenia, Belarus, Bulgaria, Croatia, Georgia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Moldova, Montenegro, Poland, Russia, Serbia, Slovakia and Ukraine. Of these, however, Croatia, Hungary, Latvia and Montenegro recognise same-sex partnerships. Same-sex marriage is unrecognised but not constitutionally banned in the constitutions of Albania, Azerbaijan, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Kazakhstan, Kosovo, North Macedonia, Turkey, and Vatican City. Eastern Europe is seen as having fewer legal rights and protections, worse living conditions, and less supportive public opinion for LGBT people than that in Western Europe.

All European countries that allow marriage also allow joint adoption by same-sex couples. Of the countries that have civil unions only, none but Andorra allow joint adoption, and only half allow step-parent adoption.

In the 2011 UN General Assembly declaration for LGBT rights, state parties were given a chance to express their support, opposition or abstention on the topic. A majority of the European countries expressed their support, and only Kazakhstan expressed its opposition. State parties that expressed abstention were Azerbaijan, Belarus, Russia, and Turkey.

In December 2020, Hungary explicitly legally banned adoption for same-sex couples within its constitution, and in June 2021 the Hungarian parliament approved a law prohibiting the showing of "any content portraying or promoting sex reassignment or homosexuality" to minors, similar to the Russian "anti-gay propaganda" law. Thirteen EU member states condemned the law, calling it a breach of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union.

The top three European countries in terms of LGBT equality according to ILGA-Europe are Malta, Belgium and Luxembourg. Western Europe is often regarded as being one of the most progressive regions in the world for LGBT people to live in.

History

Although same-sex relationships were quite common in ancient Greece, Rome and pagan Celtic societies, after Christianity became the official religion of the Roman Empire, severe laws against homosexual behaviour appeared. An edict by the Emperor Theodosius I in 390 condemned all "passive" homosexual men to death by public burning. This was followed by the Corpus Juris Civilis of Justinian I in 529, which prescribed public castration and execution for all who committed homosexual acts, both active and passive partners. In 670, Archbishop of Canterbury Theodore of Tarsus published a Penetential prescribing penances for homosexual activity comparable to those prescribed for murder and infanticide. Homosexual behaviour, called sodomy, was considered a capital crime in most European countries, and thousands of homosexual men were executed across Europe during waves of persecution in these centuries. Lesbians were less often singled out for punishment, but they also suffered persecution and execution from time to time.

Since the foundation of Poland in 966, Polish law has never defined homosexuality as a crime. Forty years after Poland lost its independence in 1795, the sodomy laws of Russia, Prussia, and Austria came into force in the partitioned Polish territory. Poland regained its independence in 1918 and abandoned the laws of the occupying powers. In 1932, Poland codified the equal age of consent for homosexuals and heterosexuals at 15.

In Turkey, homosexuality has been legal since 1858.

During the French Revolution, the French National Assembly rewrote the criminal code in 1791, omitting all reference to homosexuality. During the Napoleonic wars, homosexuality was decriminalised in territories coming under French control, such as the Netherlands and many of the pre-unification German states; however, in Germany this ended with the unification of the country under the Prussian Kaiser, as Prussia had long punished homosexuality harshly. On 6 August 1942, the Vichy government made homosexual relations with anyone under twenty-one illegal as part of its conservative agenda. Most Vichy legislation was repealed after the war—but the anti-gay Vichy law remained on the books for four decades until it was finally repealed in August 1982 when the age of consent (15) was again made the same for heterosexual as well as homosexual partners.

Nevertheless, gay men and lesbians continued to live closeted lives, since moral and social disapproval by heterosexual society remained strong across Europe for another two decades, until the modern gay rights movement began in 1969.

Various countries under dictatorships in the 20th century were very anti-homosexual, such as in the Soviet Union, in Nazi Germany and in Spain under Francisco Franco's regime. In contrast, after Poland regained independence after World War I, it went on in 1932 to become the second country in 20th-century Europe to decriminalise homosexual activity (after the Soviet Union, which had decriminalized it in 1917 under the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, but re-criminalized it in 1933 under Stalin), followed by Denmark in 1933, Iceland in 1940, Switzerland in 1942 and Sweden in 1944.

In 1956, the German Democratic Republic abolished paragraph 175 of the German penal code which outlawed homosexuality. In 1962, homosexual behaviour was decriminalized in Czechoslovakia, following the scientific research of Kurt Freund that included phallometry of gay men who appeared to have given up sexual relations with other men and established heterosexual marriages. Freund came to the conclusion that a homosexual orientation cannot be changed. However, the claim that phallometry on men was the only reason for the decriminalization of homosexual behaviour in Czechoslovakia is contradicted by the fact that it applied to women as well, as the notion of a male-specific fixity of sexual orientation as an argument for gay rights combined with the notion of female sexual plasticity is adverse to lesbian rights.

Same-sex marriage, full adoption rights and:

Legal gender change, surgery not required and:

In 1972, Sweden became the first country in the world to allow people who were transgender by legislation to surgically change their sex and provide free hormone replacement therapy.

In 1979, a number of people in Sweden called in sick with a case of being homosexual, in protest of homosexuality being classified as an illness. This was followed by an activist occupation of the main office of the National Board of Health and Welfare. Within a few months, Sweden became the first country in Europe from those that had previously defined homosexuality as an illness to remove it as such.

In 1989, Denmark was the first country in Europe, and the world, to introduce registered partnerships for same-sex couples.

In 1991, Bulgaria was the first country in Europe to ban same-sex marriage. Since then, thirteen countries have followed (Lithuania in 1992, Belarus and Moldova in 1994, Ukraine in 1996, Poland in 1997, Latvia and Serbia in 2006, Montenegro in 2007, Hungary in 2012, Croatia in 2013, Slovakia in 2014, Armenia in 2015 and Georgia in 2018).

In 2001, a next step was made, when the Netherlands opened civil marriage for same-sex couples, which made it the first country in the world to do so. Since then, eighteen other European states have followed (Belgium in 2003, Spain in 2005, Norway and Sweden in 2009, Portugal and Iceland in 2010, Denmark in 2012, France in 2013, England and Wales in 2013, Scotland in 2014, Luxembourg and Ireland in 2015, Finland, Malta, and Germany in 2017, Austria in 2019 Northern Ireland in 2020, and Switzerland in 2022.)

On 22 October 2009, the assembly of the Church of Sweden, voted strongly in favour of giving its blessing to homosexual couples, including the use of the term marriage, ("matrimony"). The new law was introduced on 1 November 2009. Under the Danish marriage law, ministers can refuse to carry out a same-sex ceremony, but the local bishop must arrange a replacement for their church building. In October 2015, the Church of Iceland voted to allow same-sex couples to marry in its churches. In 2015, the Church of Norway voted to allow same-sex marriages to take place in its churches. The decision was ratified at the annual conference on 11 April 2016. The church formally amended its marriage liturgy on 30 January 2017, replacing references to "bride and groom" with gender-neutral text. A male same-sex couple was immediately married in the church the moment the changes came into effect, on 1 February 2017.

Recent developments

Civil partnerships have been legal in Ireland since 2011. In 2013, the government held a constitutional convention which voted overwhelmingly in favour of amending the constitution in order to extend marriage rights to same-sex couples. On 22 May 2015, Irish citizens voted on whether to add the following amendment to the constitution: "Marriage may be contracted in accordance with law by two persons without distinction as to their sex". 62.1% of the electorate voted in favour of the amendment, making Ireland the first country worldwide to introduce same-sex marriage through a national referendum. Ireland's first same-sex marriage ceremonies took place in November 2015.

The Isle of Man has allowed civil partnerships since 2011, as well as Jersey in 2012. Both Crown Dependencies legalised same-sex marriage later since 22 July 2016 and since 1 July 2018, respectively.

Liechtenstein also legalised registered partnership by 68% of voters via a referendum in 2011.

On 1 January 2012, a new constitution of Hungary enacted by the government of Viktor Orbán, leader of the ruling Fidesz party, came into effect, restricting marriage to opposite-sex couples and containing no guarantees of protection from discrimination on account of sexual orientation.

In 2012, the United Kingdom government launched a public same-sex marriage consultation, intending to change the laws applying to England and Wales. Its Marriage Bill was signed into law on 17 July 2013. The Scottish government launched a similar consultation, aiming to legalise same-sex marriage by 2015. On 4 February 2014, the Scottish Parliament passed a bill to legalise same-sex marriages in Scotland as well as ending the "spousal veto" that would allow spouses to deny transgender partners the ability to change their legal gender. Same-sex marriage was extended to Northern Ireland on 21 October 2019 and the law came into effect on 13 January 2020.

In May 2013, France legalised same-sex marriage, with French president François Hollande signing a law authorising marriage and adoption by gay couples.

On 30 June 2013, Vladimir Putin, President of Russia, signed the Russian LGBT propaganda law into force, which was approved by the State Duma. The law makes distributing propaganda among minors in support of "non-traditional" sexual relationships a criminal offence.

On 1 December 2013, a referendum was held in Croatia to constitutionally define marriage as a union between a woman and a man. The vote passed, with 65.87% supporting the measure, and a turnout of 37.9%.

On 27 January 2014 in the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, Turkish Cypriot deputies passed an amendment repealing a colonial-era law that punished homosexual acts with up to five years in prison by a new Criminal Code.

On 14 April 2014, the Parliament of Malta voted in favour of the Civil Union Act which recognises same-sex couples and permits them to adopt children. On the same day the Maltese parliament also voted in favour of a constitutional amendment to ban discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity.

On 4 June 2014, the Slovak parliament overwhelmingly approved a sitting social-democratic government sponsored Constitutional amendment to ban same-sex marriage, with 102 deputies for and 18 deputies against the legislation, fulfilling a 2/3 constitutional change requirement (minimum of 100 deputies out of 150 sitting MPs) for enacting this Constitutional amendment.

On 18 June 2014, the Parliament of Luxembourg approved a bill to legalise same-sex marriage and adoption. The law was published in the official gazette on 17 July and took effect 1 January 2015.

On 15 July 2014, Croatian Parliament passed the Life Partnership Act giving same-sex couples all rights that married couples have, except for adoption. However, the Act allows a parent's life partner to become the child's partner-guardian. Partner-guardianship as an institution similar to step-child adoption in rights and responsibilities, but it does not give parental status to the parent's life partner. Criteria for partner-guardianship and step-parent adoption for opposite-sex couples are the same. Also, regardless of partner-guardianship, a parent's life partner may attain partial parental responsibility over the child either via court or consensus among the parents and life partner, even full in some cases when the court decides that it is in the child's best interest.

In September 2014, a law went into effect in Denmark effectively dropping the former practice of requiring transgender persons to undergo arduous psychiatric evaluation and castration before being allowed legal gender change. By requiring nothing more than a statement of gender identity and subsequent confirmation of the request for gender change after a waiting period of 6 months, this means that anyone wishing their legal gender marker changed can do so with no expert-evaluation and few other formal restrictions. Meanwhile, Norwegian Health Minister Bent Høie has made promises that a similar law for Norway will be drafted soon. And on 18 March 2016, the Government introduced a bill to allow legal gender change without any form of psychiatric or psychological evaluation, diagnosis or any kind of medical intervention, by people aged at least 16. Minors aged between 6 and 16 also could have that possibility with parental consent. The bill was approved by a vote of 79-13 by Parliament on 6 June. It was promulgated on 17 June and took effect on 1 July 2016.

On 9 October 2014, the Parliament of Estonia passed the Cohabitation bill by a 40–38 vote. It was signed by President Toomas Hendrik Ilves that same day and took effect on 1 January 2016.

On 27 November 2014 the Parliament of Andorra passed a Civil Union bill, legalising also joint adoption for same-sex partners. On 24 December 2014, the bill was published in the official journal, following promulgation by co-prince François Hollande as signature of one of the two co-princes was needed. It took effect on 25 December 2014.

On 12 December 2014 the Parliament of Finland passed a same-sex marriage bill by a 101–90 vote. The law was signed by President Sauli Niinistö on 20 February 2015. In order that the provisions of the framework law would be fully implementable further legislation has to be passed. The law took effect on 1 March 2017.

In January 2015, the Parliament of North Macedonia voted to constitutionally define marriage as a union solely between a man and a woman. On 9 January, the parliamentary committee on constitutional issues approved a series of amendments, including the aforementioned limitation of marriage and the additional requirement of a two-thirds majority for any future regulation of marriage, family and civil unions (a requirement previously reserved only for issues such as sovereignty and territorial questions). On 20 January, the amendments were approved in parliament by 72 votes to 4. However, in order for these amendments to be added to the constitution, a final vote was required. This final parliamentary session was commenced on 26 January but never concluded, as the ruling coalition did not obtain the two-thirds majority required. The parliamentary session on the constitutional amendments was in recess until the end of 2015, thus the amendement failed.

On 7 February 2015, Slovaks voted in a referendum to ban same-sex marriage and same-sex parental adoption. The result of the referendum was for enacting the ban proposals, with 95% and 92% votes for, respectively. However, the referendum was deemed invalid under referendum law because of a low turnout (below 50% requirement).

On 3 March 2015 the Parliament of Slovenia passed a same-sex marriage bill by a 51–28 vote. On 20 December 2015, Slovenians rejected the new same-sex marriage bill by a margin of 63% to 37%.

In November 2015, the Parliament of Cyprus approved a bill which legalised civil unions for same-sex couples in a 39–12 vote. It took effect on 9 December 2015.

A bill to legalise civil unions for same-sex couples in Greece was approved in December 2015 by its Parliament in a 194–55 vote. The law was signed by the President and took effect on 24 December 2015.

On 29 April 2016, the Parliament of the Faroe Islands, a Danish dependency, voted to extend Danish same-sex marriage legislation to the territory, excluding the possibility to be legally wed in a religious ceremony. The Danish Parliament still had to approve the exclusion of religious marriages for the Faroe Islands, unlike in Denmark where churches can perform marriages between persons of the same sex. The law within the Faroe Islands went into effect on 1 July 2017, after the ratification formality by both the Danish Parliament and royal assent.

A bill to legalise civil unions for same-sex couples in Italy was approved on 11 May 2016 by the Parliament of Italy. The law was signed by the President on 20 May 2016. It was published in the Official Gazette on 21 May and therefore entered into force on 5 June 2016.

On 21 September 2016, the States of Guernsey approved the bill to legalize same-sex marriage, in a 33–5 vote. It received Royal Assent on 14 December 2016. The law went into effect on 1 July 2017.

On 26 October 2016, the Gibraltar Parliament unanimously approved a bill to allow same-sex marriage by a vote of 15–0. It received Royal Assent 1 November 2016. The law went into effect on 15 December 2016.

On 31 January 2017, the Supreme Court of Cassation (Italy) refused, on procedural grounds, to rescind a lower judgment recognising a marriage between two French women (one of these had the right to claim Italian citizenship iure sanguinis), officiated in the French region of Nord-Pas-de-Calais. This is the first time a same-sex marriage is admitted in Italy, but the judgment does not imply that this will necessarily be the case in general terms.

Within July 2017, both the Parliaments of Germany and Malta approved bills to allow same-sex marriage. The Presidents of both countries signed the bills into law. The same-sex marriage laws within Malta went into effect on 1 September 2017 and the same-sex marriage laws within Germany went into effect on 1 October 2017.

In October 2017, the Parliamentary Assembly of the Council of Europe adopted the first intersex-specific resolution of its kind from a European intergovernmental institution, after 33 members voted in favour. The resolution called for intersex peoples right to bodily autonomy and physical integrity by calling for prohibition of "medically unnecessary sex-"normalising" surgery, sterilisation and other treatments practised on intersex children without their informed consent" It recommends the committee of ministers to bring the resolution to the attention of their governments, the need for increased psychosocial support, and calls for policymakers to "ensure that anti-discrimination legislation effectively applies to and protects intersex people."

On 5 December 2017, the Constitutional Court of Austria struck down the ban on same-sex marriage as unconstitutional. Same-sex marriage became legal on 1 January 2019.

In late 2018 San Marino parliament voted to legalise civil unions with stepchild adoption rights. The law to permit civil unions became fully operational on 11 February 2019, following a number of further legal and administrative changes.

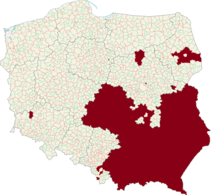

On 18 December 2019, the European Parliament voted, 463 to 107, to condemn the more than 80 LGBT-free zones in Poland.

On 26 September 2021, nearly two thirds of Swiss voters agreed to legalise civil marriage and the right to adopt children for same-sex couples in an optional referendum, after the National Council and the Council of States had both approved the aforementioned legalisations on 18 December 2020. The new law has taken effect on 1 July 2022.

On 20 June 2023, the Parliament of Estonia approved a bill to allow same-sex marriage by a vote of 55–34. It will take effect 1 January 2024.

Public opinion around Europe

| Eurobarometer 2019: % of people in each country who agree with the statement that "Gay, lesbian and bisexual people should have the same rights as heterosexual people." | |

| Country | Percentage |

|---|---|

| 98% | |

| 97% | |

| 91% | |

| 90% | |

| 89% | |

| 88% | |

| 87% | |

| 85% | |

| 84% | |

| 83% | |

| 80% | |

| 78% | |

| 73% | |

| 70% | |

| 68% | |

| 64% | |

| 64% | |

| 63% | |

| 57% | |

| 53% | |

| 53% | |

| 49% | |

| 49% | |

| 48% | |

| 44% | |

| 39% | |

| 38% | |

| 31% | |

In a 2002 Pew Global Attitudes Project surveyed by the Pew Research Center, showed majorities in every Western European nation said homosexuality should be accepted by society, while most Russians, Poles and Ukrainians disagreed. According to pollster Gallup Europe in 2003, women, younger generations, and the highly educated are more likely to support same-sex marriage and adoption rights for gay people than other demographics.

A Eurobarometer in 2006 surveying up to 30,000 people from each European Union country, showed split opinion around the then 27 member states on the issue of same-sex marriage. The majority of support came from the Netherlands (82%), Sweden (71%), Denmark (69%), Belgium (62%), Luxembourg (58%), Spain (56%), Finland (54%), Germany (52%) and the Czech Republic (52%). All other countries within the EU had below 50% support; with Romania (11%), Latvia (12%), Cyprus (14%), Bulgaria (15%), Greece (15%), Lithuania (17%), Poland (17%), Hungary (18%) and Malta (18%) at the other end of the list. Same-sex adoption had majority support from only two countries: Netherlands at 69% and Sweden at 51% and the least support from Poland and Malta on 7%, respectively.

A more recent survey carried out in October 2008 by The Observer affirmed that a small majority of Britons—55%—support same-sex marriage. A 2013 poll shows that the majority of the Irish public support same-sex marriage and adoption, 73% and 60%, respectively. France has support for same-sex marriage at 62%, and Russian at 14%. Italy has support for the 'Civil Partnership Law' between people of the same gender at 45% with 47% opposed. In 2009 58.9% of Italians supported civil unions, while a 40.4% minority supported same-sex marriage. In 2010, 63.9% of Greeks supported same-sex partnerships, while a 38.5% minority supported same-sex marriage. In 2012 a poll by MaltaToday showed that 41% of Maltese supported same-sex marriage, with support increasing to 60% amongst the 18–35 age group. In a 2013 opinion poll conducted by CBOS, 65% of Poles were against same-sex civil unions, 72% of Poles were against same-sex marriage, 88% were against adoption by same-sex couples, and 68% were against lesbian, gay, or bisexual people publicly showing their way of life. In Croatia, a poll from November 2013 revealed that 59% of Croats think that marriage should be constitutionally defined as a union between a man and a woman, while 31% do not agree with the idea. A CBOS opinion poll from February 2014 found that 70% of Poles believe same-sex sexual activity is morally unacceptable, while only 22% believed it is morally acceptable.

Public support for same-sex marriage from EU member states as measured from a 2015 poll is the greatest in the Netherlands (91%), Sweden (90%), Denmark (87%), Spain (84%), Ireland (80%), Belgium (77%), Luxembourg (75%), the United Kingdom (71%) and France (71%). In recent years, support has risen most significantly in Malta, from 18% in 2006 to 65% in 2015 and in Ireland from 41% in 2006 to 80% in 2015.

After the approval of same-sex marriage in Portugal in January 2010, 52% of the Portuguese population stated that they were in favor of the legislation. In 2008, 58% of the Norwegian voters supported same-sex marriage, which was introduced in the same year, and 31 percent were against it. In January 2013, 54.1% of Italians respondents supported same-sex marriage. In a late January 2013 survey, 77.2% of Italians respondents supported the recognition of same-sex unions.

In Greece support more than tripled between 2006 and 2017. In 2006 15% responded that they agreed with same-sex marriages being allowed throughout Europe. In 2017 according to a survey 50.04% of Greeks agreed with gay marriage. A more recent survey in 2020 showed that 56% of the Greek population accept gay marriage.

In Ireland, a 2008 survey revealed 84% of people supported civil unions for same-sex couples (and 58% for same-sex marriage), while a 2010 survey showed 67% supported same-sex marriage by 2012 this figure had risen to 73% in support. On 22 May 2015, 62.1% of the electorate voted to enshrine same-sex marriage in the Irish constitution as equal to heterosexual marriage.

A March 2013 survey by Taloustutkimus found that 58% of Finns supported same-sex marriage.

In Croatia, a poll conducted in November 2013 revealed that 59% of Croats think that marriage should be constitutionally defined as a union between a man and a woman, while 31% do not agree with the idea.

In Poland a 2013 public poll revealed that 70% of Poles reject the idea of registered partnerships. Another survey in February 2013 revealed that 55% were against and 38% of Poles support the idea of registered partnerships for same-sex couples.

In the European Union, support tends to be the lowest in Bulgaria, Latvia, Hungary, Romania, Slovakia, and Lithuania. The average percentage of support for same-sex marriage in the European Union as of 2006 when it had 25 members was 44%, which had descended from a previous percentage of 53%. The change was caused by more socially conservative nations joining the EU. In 2015, with 28 members, average support was at 61%. A 2015 NDI public opinion poll shows that only 10% of the population in the Balkans (Serbia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Albania, Kosovo, Montenegro and North Macedonia) believe LGBTI marriages are acceptable, in contrast to 88% who think they're unacceptable.