Supernatural refers to phenomena or entities that are beyond the laws of nature. The term is derived from Medieval Latin supernaturalis, from Latin super- (above, beyond, or outside of) + natura (nature). Although the corollary term "nature" has had multiple meanings since the ancient world, the term "supernatural" emerged in the Middle Ages and did not exist in the ancient world.

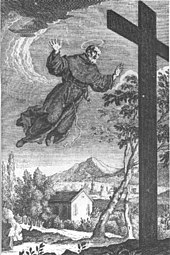

The supernatural is featured in folklore and religious contexts, but can also feature as an explanation in more secular contexts, as in the cases of superstitions or belief in the paranormal. The term is attributed to non-physical entities, such as angels, demons, gods and spirits. It also includes claimed abilities embodied in or provided by such beings, including magic, telekinesis, levitation, precognition and extrasensory perception.

The supernatural is hypernymic to religion. Religions are standardized supernaturalist worldviews, or at least more complete than single supernaturalist views. Supernaturalism is the adherence to the supernatural (beliefs, and not violations of causality and the physical laws).

Etymology and history of the concept

Occurring as both an adjective and a noun, antecedents of the modern English compound supernatural enter the language from two sources: via Middle French (supernaturel) and directly from the Middle French's term's ancestor, post-Classical Latin (supernaturalis). Post-classical Latin supernaturalis first occurs in the 6th century, composed of the Latin prefix super- and nātūrālis (see nature). The earliest known appearance of the word in the English language occurs in a Middle English translation of Catherine of Siena's Dialogue (orcherd of Syon, around 1425; Þei haue not þanne þe supernaturel lyȝt ne þe liȝt of kunnynge, bycause þei vndirstoden it not).

The semantic value of the term has shifted over the history of its use. Originally the term referred exclusively to Christian understandings of the world. For example, as an adjective, the term can mean "belonging to a realm or system that transcends nature, as that of divine, magical, or ghostly beings; attributed to or thought to reveal some force beyond scientific understanding or the laws of nature; occult, paranormal" or "more than what is natural or ordinary; unnaturally or extraordinarily great; abnormal, extraordinary". Obsolete uses include "of, relating to, or dealing with metaphysics". As a noun, the term can mean "a supernatural being", with a particularly strong history of employment in relation to entities from the mythologies of the indigenous peoples of the Americas.

History of the concept

The ancient world had no word that resembled "supernatural". Dialogues from Neoplatonic philosophy in the third century AD influenced the development of the concept of the supernatural, which later evolved through Christian theology. The term nature had existed since antiquity, with Latin authors like Augustine using the word and its cognates at least 600 times in City of God. In the medieval period, "nature" had ten different meanings and "natural" had eleven different meanings. Peter Lombard, a medieval scholastic of the 12th century, explored causes beyond nature, questioning how certain phenomena could be attributed solely to God. In his writings, he used the term praeter naturam to describe these occurrences. In the scholastic period, Thomas Aquinas classified miracles into three categories: "above nature", "beyond nature" and "against nature". In doing so, he sharpened the distinction between nature and miracles more than the early Church Fathers had done. As a result, he had created a dichotomy of sorts of the natural and supernatural. Though the phrase "supra naturam" was used since the 4th century AD, it was in the 1200s that Thomas Aquinas used the term "supernaturalis". Despite this, the term had to wait until the end of the medieval period before it became more popularly used. The discussions on "nature" from the scholastic period were diverse and unsettled with some postulating that even miracles are natural and that natural magic was a natural part of the world.

Epistemology and metaphysics

The metaphysical considerations of the existence of the supernatural can be difficult to approach as an exercise in philosophy or theology because any dependencies on its antithesis, the natural, will ultimately have to be inverted or rejected. One complicating factor is that there is disagreement about the definition of "natural" and the limits of naturalism. Concepts in the supernatural domain are closely related to concepts in religious spirituality and occultism or spiritualism.

For sometimes we use the word nature for that Author of nature whom the schoolmen, harshly enough, call natura naturans, as when it is said that nature hath made man partly corporeal and partly immaterial. Sometimes we mean by the nature of a thing the essence, or that which the schoolmen scruple not to call the quiddity of a thing, namely, the attribute or attributes on whose score it is what it is, whether the thing be corporeal or not, as when we attempt to define the nature of an angle, or of a triangle, or of a fluid body, as such. Sometimes we take nature for an internal principle of motion, as when we say that a stone let fall in the air is by nature carried towards the centre of the earth, and, on the contrary, that fire or flame does naturally move upwards toward firmament. Sometimes we understand by nature the established course of things, as when we say that nature makes the night succeed the day, nature hath made respiration necessary to the life of men. Sometimes we take nature for an aggregate of powers belonging to a body, especially a living one, as when physicians say that nature is strong or weak or spent, or that in such or such diseases nature left to herself will do the cure. Sometimes we take nature for the universe, or system of the corporeal works of God, as when it is said of a phoenix, or a chimera, that there is no such thing in nature, i.e. in the world. And sometimes too, and that most commonly, we would express by nature a semi-deity or other strange kind of being, such as this discourse examines the notion of.

And besides these more absolute acceptions, if I may so call them, of the word nature, it has divers others (more relative), as nature is wont to be set or in opposition or contradistinction to other things, as when we say of a stone when it falls downwards that it does it by a natural motion, but that if it be thrown upwards its motion that way is violent. So chemists distinguish vitriol into natural and fictitious, or made by art, i.e. by the intervention of human power or skill; so it is said that water, kept suspended in a sucking pump, is not in its natural place, as that is which is stagnant in the well. We say also that wicked men are still in the state of nature, but the regenerate in a state of grace; that cures wrought by medicines are natural operations; but the miraculous ones wrought by Christ and his apostles were supernatural.— Robert Boyle, A Free Enquiry into the Vulgarly Received Notion of Nature

Nomological possibility is possibility under the actual laws of nature. Most philosophers since David Hume have held that the laws of nature are metaphysically contingent—that there could have been different natural laws than the ones that actually obtain. If so, then it would not be logically or metaphysically impossible, for example, for you to travel to Alpha Centauri in one day; it would just have to be the case that you could travel faster than the speed of light. But of course there is an important sense in which this is not nomologically possible; given that the laws of nature are what they are. In the philosophy of natural science, impossibility assertions come to be widely accepted as overwhelmingly probable rather than considered proved to the point of being unchallengeable. The basis for this strong acceptance is a combination of extensive evidence of something not occurring, combined with an underlying scientific theory, very successful in making predictions, whose assumptions lead logically to the conclusion that something is impossible. While an impossibility assertion in natural science can never be absolutely proved, it could be refuted by the observation of a single counterexample. Such a counterexample would require that the assumptions underlying the theory that implied the impossibility be re-examined. Some philosophers, such as Sydney Shoemaker, have argued that the laws of nature are in fact necessary, not contingent; if so, then nomological possibility is equivalent to metaphysical possibility.

The term supernatural is often used interchangeably with paranormal or preternatural—the latter typically limited to an adjective for describing abilities which appear to exceed what is possible within the boundaries of the laws of physics. Epistemologically, the relationship between the supernatural and the natural is indistinct in terms of natural phenomena that, ex hypothesi, violate the laws of nature, in so far as such laws are realistically accountable.

Parapsychologists use the term psi to refer to an assumed unitary force underlying the phenomena they study. Psi is defined in the Journal of Parapsychology as "personal factors or processes in nature which transcend accepted laws" (1948: 311) and "which are non-physical in nature" (1962:310), and it is used to cover both extrasensory perception (ESP), an "awareness of or response to an external event or influence not apprehended by sensory means" (1962:309) or inferred from sensory knowledge, and psychokinesis (PK), "the direct influence exerted on a physical system by a subject without any known intermediate energy or instrumentation" (1945:305).

— Michael Winkelman, Current Anthropology

Views on the "supernatural" vary, for example it may be seen as:

- indistinct from nature. From this perspective, some events occur according to the laws of nature, and others occur according to a separate set of principles external to known nature. For example, in Scholasticism, it was believed that God was capable of performing any miracle so long as it did not lead to a logical contradiction. Some religions posit immanent deities, however, and do not have a tradition analogous to the supernatural; some believe that everything anyone experiences occurs by the will (occasionalism), in the mind (neoplatonism), or as a part (nondualism) of a more fundamental divine reality (platonism).

- incorrect human attribution. In this view all events have natural and only natural causes. They believe that human beings ascribe supernatural attributes to purely natural events, such as lightning, rainbows, floods and the origin of life.

Cross cultural studies

Anthropological studies across cultures indicate that people do not hold or use natural and supernatural explanations in a mutually exclusive or dichotomous fashion. Instead, the reconciliation of natural and supernatural explanations is normal and pervasive across cultures. Cross cultural studies indicate that there is coexistence of natural and supernatural explanations in both adults and children for explaining numerous things about the world, such as illness, death, and origins. Context and cultural input play a large role in determining when and how individuals incorporate natural and supernatural explanations. The coexistence of natural and supernatural explanations in individuals may be the outcomes two distinct cognitive domains: one concerned with the physical-mechanical relations and another with social relations. Studies on indigenous groups have allowed for insights on how such coexistence of explanations may function.

Supernatural concepts

Deity

A deity (/ˈdiːəti/ or /ˈdeɪ.əti/ ) is a supernatural being considered divine or sacred. The Oxford Dictionary of English defines deity as "a god or goddess (in a polytheistic religion)", or anything revered as divine. C. Scott Littleton defines a deity as "a being with powers greater than those of ordinary humans, but who interacts with humans, positively or negatively, in ways that carry humans to new levels of consciousness, beyond the grounded preoccupations of ordinary life." A male deity is a god, while a female deity is a goddess.

Religions can be categorized by how many deities they worship. Monotheistic religions accept only one deity (predominantly referred to as God), polytheistic religions accept multiple deities. Henotheistic religions accept one supreme deity without denying other deities, considering them as equivalent aspects of the same divine principle; and nontheistic religions deny any supreme eternal creator deity but accept a pantheon of deities which live, die and are reborn just like any other being.

Various cultures have conceptualized a deity differently than a monotheistic God. A deity need not be omnipotent, omnipresent, omniscient, omnibenevolent or eternal, The monotheistic God, however, does have these attributes. Monotheistic religions typically refer to God in masculine terms, while other religions refer to their deities in a variety of ways – masculine, feminine, androgynous and gender neutral.

Historically, many ancient cultures – such as Ancient India, Ancient Egyptian, Ancient Greek, Ancient Roman, Nordic and Asian culture – personified natural phenomena, variously as either their conscious causes or simply their effects, respectively. Some Avestan and Vedic deities were viewed as ethical concepts. In Indian religions, deities have been envisioned as manifesting within the temple of every living being's body, as sensory organs and mind. Deities have also been envisioned as a form of existence (Saṃsāra) after rebirth, for human beings who gain merit through an ethical life, where they become guardian deities and live blissfully in heaven, but are also subject to death when their merit runs out.

Angel

An angel is generally a supernatural being found in various religions and mythologies. In Abrahamic religions and Zoroastrianism, angels are often depicted as benevolent celestial beings who act as intermediaries between God or Heaven and Earth. Other roles of angels include protecting and guiding human beings and carrying out God's tasks. Within Abrahamic religions, angels are often organized into hierarchies, although such rankings may vary between sects in each religion, and are given specific names or titles, such as Gabriel or "Destroying angel." The term "angel" has also been expanded to various notions of spirits or figures found in other religious traditions. The theological study of angels is known as "angelology".

In fine art, angels are usually depicted as having the shape of human beings of extraordinary beauty; they are often identified using the symbols of bird wings, halos and light.

Prophecy

Prophecy involves a process in which messages are communicated by a god to a prophet. Such messages typically involve inspiration, interpretation, or revelation of divine will concerning the prophet's social world and events to come (compare divine knowledge). Prophecy is not limited to any one culture. It is a common property to all known ancient societies around the world, some more than others. Many systems and rules about prophecy have been proposed over several millennia.

Revelation

In religion and theology, revelation is the revealing or disclosing of some form of truth or knowledge through communication with a deity or other supernatural entity or entities.

Some religions have religious texts which they view as divinely or supernaturally revealed or inspired. For instance, Orthodox Jews, Christians and Muslims believe that the Torah was received from Yahweh on biblical Mount Sinai. Most Christians believe that both the Old Testament and the New Testament were inspired by God. Muslims believe the Quran was revealed by God to Muhammad word by word through the angel Gabriel (Jibril). In Hinduism, some Vedas are considered apauruṣeya, "not human compositions", and are supposed to have been directly revealed, and thus are called śruti, "what is heard". Aleister Crowley stated that The Book of the Law had been revealed to him through a higher being that called itself Aiwass.

A revelation communicated by a supernatural entity reported as being present during the event is called a vision. Direct conversations between the recipient and the supernatural entity, or physical marks such as stigmata, have been reported. In rare cases, such as that of Saint Juan Diego, physical artifacts accompany the revelation. The Roman Catholic concept of interior locution includes just an inner voice heard by the recipient.

In the Abrahamic religions, the term is used to refer to the process by which God reveals knowledge of himself, his will and his divine providence to the world of human beings. In secondary usage, revelation refers to the resulting human knowledge about God, prophecy and other divine things. Revelation from a supernatural source plays a less important role in some other religious traditions such as Buddhism, Confucianism and Taoism.

Reincarnation

Reincarnation is the philosophical or religious concept that an aspect of a living being starts a new life in a different physical body or form after each biological death. It is also called rebirth or transmigration, and is a part of the Saṃsāra doctrine of cyclic existence. It is a central tenet of all major Indian religions, namely Jainism, Hinduism, Buddhism and Sikhism. The idea of reincarnation is found in many ancient cultures, and a belief in rebirth/metempsychosis was held by Greek historic figures, such as Pythagoras, Socrates and Plato. It is also a common belief of various ancient and modern religions such as Spiritism, Theosophy and Eckankar and as an esoteric belief in many streams of Orthodox Judaism. It is found as well in many tribal societies around the world, in places such as Australia, East Asia, Siberia and South America.

Although the majority of denominations within Christianity and Islam do not believe that individuals reincarnate, particular groups within these religions do refer to reincarnation; these groups include the mainstream historical and contemporary followers of Cathars, Alawites, the Druze and the Rosicrucians. The historical relations between these sects and the beliefs about reincarnation that were characteristic of Neoplatonism, Orphism, Hermeticism, Manicheanism and Gnosticism of the Roman era as well as the Indian religions, have been the subject of recent scholarly research. Unity Church and its founder Charles Fillmore teaches reincarnation.

In recent decades, many Europeans and North Americans have developed an interest in reincarnation, and many contemporary works mention it.

Karma

Karma (/ˈkɑːrmə/; Sanskrit: कर्म, romanized: karma, IPA: [ˈkɐɽmɐ] ; Pali: kamma) means action, work or deed; it also refers to the spiritual principle of cause and effect where intent and actions of an individual (cause) influence the future of that individual (effect). Good intent and good deeds contribute to good karma and future happiness, while bad intent and bad deeds contribute to bad karma and future suffering.

With origins in ancient India's Vedic civilization, the philosophy of karma is closely associated with the idea of rebirth in many schools of Indian religions (particularly Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism) as well as Taoism. In these schools, karma in the present affects one's future in the current life, as well as the nature and quality of future lives – one's saṃsāra.

Christian theology

In Catholic theology, the supernatural order is, according to New Advent, defined as "the ensemble of effects exceeding the powers of the created universe and gratuitously produced by God for the purpose of raising the rational creature above its native sphere to a God-like life and destiny." The Modern Catholic Dictionary defines it as "the sum total of heavenly destiny and all the divinely established means of reaching that destiny, which surpass the mere powers and capacities of human nature."

Process theology

Process theology is a school of thought influenced by the metaphysical process philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead (1861–1947) and further developed by Charles Hartshorne (1897–2000).

It is not possible, in process metaphysics, to conceive divine activity as a "supernatural" intervention into the "natural" order of events. Process theists usually regard the distinction between the supernatural and the natural as a by-product of the doctrine of creation ex nihilo. In process thought, there is no such thing as a realm of the natural in contrast to that which is supernatural. On the other hand, if "the natural" is defined more neutrally as "what is in the nature of things," then process metaphysics characterizes the natural as the creative activity of actual entities. In Whitehead's words, "It lies in the nature of things that the many enter into complex unity" (Whitehead 1978, 21). It is tempting to emphasize process theism's denial of the supernatural and thereby highlight that the processed God cannot do in comparison what the traditional God could do (that is, to bring something from nothing). In fairness, however, equal stress should be placed on process theism's denial of the natural (as traditionally conceived) so that one may highlight what the creatures cannot do, in traditional theism, in comparison to what they can do in process metaphysics (that is, to be part creators of the world with God).

— Donald Viney, "Process Theism" in The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy

Heaven

Heaven, or the heavens, is a common religious, cosmological, or transcendent place where beings such as gods, angels, spirits, saints, or venerated ancestors are said to originate, be enthroned, or live. According to the beliefs of some religions, heavenly beings can descend to Earth or incarnate, and earthly beings can ascend to heaven in the afterlife, or in exceptional cases enter heaven alive.

Heaven is often described as a "higher place", the holiest place, a Paradise, in contrast to hell or the Underworld or the "low places" and universally or conditionally accessible by earthly beings according to various standards of divinity, goodness, piety, faith, or other virtues or right beliefs or simply the will of God. Some believe in the possibility of a heaven on Earth in a world to come.

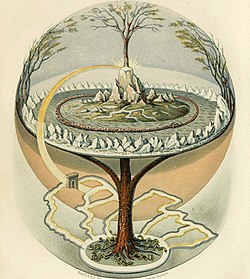

Another belief is in an axis mundi or world tree which connects the heavens, the terrestrial world and the underworld. In Indian religions, heaven is considered as Svarga loka, and the soul is again subjected to rebirth in different living forms according to its karma. This cycle can be broken after a soul achieves Moksha or Nirvana. Any place of existence, either of humans, souls or deities, outside the tangible world (Heaven, Hell, or other) is referred to as otherworld.

Underworld

The underworld is the supernatural world of the dead in various religious traditions, located below the world of the living. Chthonic is the technical adjective for things of the underworld.

The concept of an underworld is found in almost every civilization and "may be as old as humanity itself". Common features of underworld myths are accounts of living people making journeys to the underworld, often for some heroic purpose. Other myths reinforce traditions that entrance of souls to the underworld requires a proper observation of ceremony, such as the ancient Greek story of the recently dead Patroclus haunting Achilles until his body could be properly buried for this purpose. Persons having social status were dressed and equipped in order to better navigate the underworld.

A number of mythologies incorporate the concept of the soul of the deceased making its own journey to the underworld, with the dead needing to be taken across a defining obstacle such as a lake or a river to reach this destination. Imagery of such journeys can be found in both ancient and modern art. The descent to the underworld has been described as "the single most important myth for Modernist authors".

Spirit

A spirit is a supernatural being, often but not exclusively a non-physical entity; such as a ghost, fairy, jinn or angel. The concepts of a person's spirit and soul, often also overlap, as both are either contrasted with or given ontological priority over the body and both are believed to survive bodily death in some religions, and "spirit" can also have the sense of "ghost", i.e. a manifestation of the spirit of a deceased person. In English Bibles, "the Spirit" (with a capital "S"), specifically denotes the Holy Spirit.

Spirit is often used metaphysically to refer to the consciousness or personality.

Historically, it was also used to refer to a "subtle" as opposed to "gross" material substance, as in the famous last paragraph of Sir Isaac Newton's Principia Mathematica.

Demon

A demon (from Koine Greek δαιμόνιον daimónion) is a supernatural and often malevolent being prevalent in religion, occultism, literature, fiction, mythology and folklore.

In Ancient Near Eastern religions as well as in the Abrahamic traditions, including ancient and medieval Christian demonology, a demon is considered a harmful spiritual entity, below the heavenly planes which may cause demonic possession, calling for an exorcism. In Western occultism and Renaissance magic, which grew out of an amalgamation of Greco-Roman magic, Jewish Aggadah and Christian demonology, a demon is believed to be a spiritual entity that may be conjured and controlled.

Magic

Magic or sorcery is the use of rituals, symbols, actions, gestures, or language with the aim of utilizing supernatural forces. Belief in and practice of magic has been present since the earliest human cultures and continues to have an important spiritual, religious and medicinal role in many cultures today. The term magic has a variety of meanings, and there is no widely agreed upon definition of what it is.

Scholars of religion have defined magic in different ways. One approach, associated with the anthropologists Edward Tylor and James G. Frazer, suggests that magic and science are opposites. An alternative approach, associated with the sociologists Marcel Mauss and Emile Durkheim, argues that magic takes place in private, while religion is a communal and organised activity. Many scholars of religion have rejected the utility of the term magic and it has become increasingly unpopular within scholarship since the 1990s.

The term magic comes from the Old Persian magu, a word that applied to a form of religious functionary about which little is known. During the late sixth and early fifth centuries BC, this term was adopted into Ancient Greek, where it was used with negative connotations, to apply to religious rites that were regarded as fraudulent, unconventional and dangerous. This meaning of the term was then adopted by Latin in the first century BC. The concept was then incorporated into Christian theology during the first century AD, where magic was associated with demons and thus defined against religion. This concept was pervasive throughout the Middle Ages, although in the early modern period Italian humanists reinterpreted the term in a positive sense to establish the idea of natural magic. Both negative and positive understandings of the term were retained in Western culture over the following centuries, with the former largely influencing early academic usages of the word.

Throughout history, there have been examples of individuals who practiced magic and referred to themselves as magicians. This trend has proliferated in the modern period, with a growing number of magicians appearing within the esoteric milieu. British esotericist Aleister Crowley described magic as the art of effecting change in accordance with will.

Divination

Divination (from Latin divinare "to foresee, to be inspired by a god", related to divinus, divine) is the attempt to gain insight into a question or situation by way of an occultic, standardized process or ritual. Used in various forms throughout history, diviners ascertain their interpretations of how a querent should proceed by reading signs, events, or omens, or through alleged contact with a supernatural agency.

Divination can be seen as a systematic method with which to organize what appear to be disjointed, random facets of existence such that they provide insight into a problem at hand. If a distinction is to be made between divination and fortune-telling, divination has a more formal or ritualistic element and often contains a more social character, usually in a religious context, as seen in traditional African medicine. Fortune-telling, on the other hand, is a more everyday practice for personal purposes. Particular divination methods vary by culture and religion.

Divination is dismissed by the scientific community and skeptics as being superstition. In the 2nd century, Lucian devoted a witty essay to the career of a charlatan, "Alexander the false prophet", trained by "one of those who advertise enchantments, miraculous incantations, charms for your love-affairs, visitations for your enemies, disclosures of buried treasure and successions to estates".

Witchcraft

Witchcraft or witchery broadly means the practice of and belief in magical skills and abilities exercised by solitary practitioners and groups. Witchcraft is a broad term that varies culturally and societally and thus can be difficult to define with precision, and cross-cultural assumptions about the meaning or significance of the term should be applied with caution. Witchcraft often occupies a religious divinatory or medicinal role and is often present within societies and groups whose cultural framework includes a magical world view.

Miracle

A miracle is an event not explicable by natural or scientific laws. Such an event may be attributed to a supernatural being (a deity), a miracle worker, a saint or a religious leader.

Informally, the word "miracle" is often used to characterise any beneficial event that is statistically unlikely but not contrary to the laws of nature, such as surviving a natural disaster, or simply a "wonderful" occurrence, regardless of likelihood, such as a birth. Other such miracles might be: survival of an illness diagnosed as terminal, escaping a life-threatening situation or 'beating the odds'. Some coincidences may be seen as miracles.

A true miracle would, by definition, be a non-natural phenomenon, leading many rational and scientific thinkers to dismiss them as physically impossible (that is, requiring violation of established laws of physics within their domain of validity) or impossible to confirm by their nature (because all possible physical mechanisms can never be ruled out). The former position is expressed for instance by Thomas Jefferson and the latter by David Hume. Theologians typically say that, with divine providence, God regularly works through nature yet, as a creator, is free to work without, above, or against it as well. The possibility and probability of miracles are then equal to the possibility and probability of the existence of God.

Skepticism

Skepticism (American English) or scepticism (British English; see spelling differences) is generally any questioning attitude or doubt towards one or more items of putative knowledge or belief. It is often directed at domains such as the supernatural, morality (moral skepticism), religion (skepticism about the existence of God), or knowledge (skepticism about the possibility of knowledge, or of certainty).

In fiction and popular culture

Supernatural entities and powers are common in various works of fantasy. Examples include the television shows Supernatural and The X-Files, the magic of the Harry Potter series, The Lord of the Rings series, The Wheel of Time series and A Song of Ice and Fire series.