| Archaeopteryx Temporal range: Late Jurassic (Tithonian),

| |

|---|---|

| |

| The Berlin Archaeopteryx specimen (A. siemensii) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Clade: | Dinosauria |

| Clade: | Saurischia |

| Clade: | Theropoda |

| Clade: | Paraves |

| Family: | †Archaeopterygidae |

| Genus: | †Archaeopteryx Meyer, 1861 (conserved name) |

| Type species | |

| †Archaeopteryx lithographica Meyer, 1861 (conserved name)

| |

| Other species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

Archaeopteryx (/ˌɑːrkiːˈɒptərɪks/ ⓘ; lit. 'ancient wing'), sometimes referred to by its German name, "Urvogel" (lit. Primeval Bird) is a genus of bird-like dinosaurs. The genus name derives from the Ancient Greek ἀρχαῖος (archaîos), meaning "ancient", and πτέρυξ (ptérux), meaning "feather, wing". Between the late 19th century and the early 21st century, Archaeopteryx was generally accepted by palaeontologists and popular reference books as the oldest known bird (member of the group Avialae). Older potential avialans have since been identified, including Anchiornis, Xiaotingia, Aurornis, and Baminornis.

Archaeopteryx lived in the Late Jurassic around 150 million years ago, in what is now southern Germany, during a time when Europe was an archipelago of islands in a shallow warm tropical sea, much closer to the equator than it is now. Similar in size to a Eurasian magpie, with the largest individuals possibly attaining the size of a raven, the largest species of Archaeopteryx could grow to about 50 cm (20 in) in length. Despite their small size, broad wings, and inferred ability to fly or glide, Archaeopteryx had more in common with other small Mesozoic dinosaurs than with modern birds. In particular, they shared the following features with the dromaeosaurids and troodontids: jaws with sharp teeth, three fingers with claws, a long bony tail, hyperextensible second toes ("killing claw"), feathers (which also suggest warm-bloodedness), and various features of the skeleton.

These features make Archaeopteryx a clear candidate for a transitional fossil between non-avian dinosaurs and avian dinosaurs (birds). Thus, Archaeopteryx plays an important role, not only in the study of the origin of birds, but in the study of dinosaurs. It was named from a single feather in 1861, the identity of which has been controversial. That same year, the first complete specimen of Archaeopteryx was announced. Over the years, twelve more fossils of Archaeopteryx have surfaced. Despite variation among these fossils, most experts regard all the remains that have been discovered as belonging to a single species or at least genus, although this is still debated.

Most of these 14 fossils include impressions of feathers. Because these feathers are of an advanced form (flight feathers), these fossils are evidence that the evolution of feathers began before the Late Jurassic. The type specimen of Archaeopteryx was discovered just two years after Charles Darwin published On the Origin of Species. Archaeopteryx seemed to confirm Darwin's theories and has since become a key piece of evidence for the origin of birds, the transitional fossils debate, and confirmation of evolution. Archaeopteryx was long considered to be the beginning of the evolutionary tree of birds. However, in recent years, the discovery of several small, feathered dinosaurs has created a mystery for palaeontologists, raising questions about which animals are the ancestors of modern birds and which are their relatives.

History of discovery

Over the years, fourteen body fossil specimens of Archaeopteryx have been found. All of the fossils come from the limestone deposits, quarried for centuries, near Solnhofen, Germany. These quarries excavate sediments from the Solnhofen Limestone formation and related units. The initial specimen was the first dinosaur to be discovered with feathers.

The initial discovery, a single feather, was unearthed in 1860 or 1861 and described in 1861 by Hermann von Meyer. It is now in the Natural History Museum of Berlin. Though it was the initial holotype, there were indications that it might not have been from the same animal as the body fossils. In 2019 it was reported that laser imaging had revealed the structure of the quill (which had not been visible since some time after the feather was described), and that the feather was inconsistent with the morphology of all other Archaeopteryx feathers known, leading to the conclusion that it originated from another dinosaur. This conclusion was challenged in 2020 as being unlikely; the feather was identified on the basis of morphology as most likely having been an upper major primary covert feather.

The first skeleton, known as the London Specimen (BMNH 37001), was unearthed in 1861 near Langenaltheim, Germany, and perhaps given to local physician Karl Häberlein in return for medical services. He then sold it for £700 (roughly £83,000 in 2020) to the Natural History Museum in London, where it remains. Missing most of its head and neck, it was described in 1863 by Richard Owen as Archaeopteryx macrura, allowing for the possibility it did not belong to the same species as the feather. In the subsequent fourth edition of his On the Origin of Species, Charles Darwin described how some authors had maintained "that the whole class of birds came suddenly into existence during the eocene period; but now we know, on the authority of Professor Owen, that a bird certainly lived during the deposition of the upper greensand; and still more recently, that strange bird, the Archaeopteryx, with a long lizard-like tail, bearing a pair of feathers on each joint, and with its wings furnished with two free claws, has been discovered in the oolitic slates of Solnhofen. Hardly any recent discovery shows more forcibly than this how little we as yet know of the former inhabitants of the world."

The genus name derives from the Ancient Greek ἀρχαῖος (archaîos), meaning "ancient", and πτέρυξ (ptérux), meaning "feather, wing". Meyer suggested this in his description. At first he referred to a single feather which appeared to resemble a modern bird's remex (wing feather), but he had heard of and been shown a rough sketch of the London specimen, to which he referred as a "Skelett eines mit ähnlichen Federn bedeckten Tieres" ("skeleton of an animal covered in similar feathers"). In German, this ambiguity is resolved by the term Schwinge which does not necessarily mean a wing used for flying. Urschwinge was the favoured translation of Archaeopteryx among German scholars in the late nineteenth century. In English, 'ancient pinion' offers a rough approximation to this.

Since then, twelve specimens have been recovered:

The Berlin Specimen (HMN 1880/81) was discovered in 1874 or 1875 on the Blumenberg near Eichstätt, Germany, by farmer Jakob Niemeyer. He sold this precious fossil for the money to buy a cow in 1876, to innkeeper Johann Dörr, who again sold it to Ernst Otto Häberlein, the son of K. Häberlein. Placed on sale between 1877 and 1881, with potential buyers including O. C. Marsh of Yale University's Peabody Museum, it eventually was bought for 20,000 Goldmark by the Berlin's Natural History Museum, where it now is displayed. The transaction was financed by Ernst Werner von Siemens, founder of the company that bears his name. Described in 1884 by Wilhelm Dames, it is the most complete specimen, and the first with a complete head. In 1897 it was named by Dames as a new species, A. siemensii; though often considered a synonym of A. lithographica, several 21st century studies have concluded that it is a distinct species which includes the Berlin, Munich, and Thermopolis specimens.

Composed of a torso, the Maxberg Specimen (S5) was discovered in 1956 near Langenaltheim; it was brought to the attention of professor Florian Heller in 1958 and described by him in 1959. The specimen is missing its head and tail, although the rest of the skeleton is mostly intact. Although it was once exhibited at the Maxberg Museum in Solnhofen, it is currently missing. It belonged to Eduard Opitsch, who loaned it to the museum until 1974. After his death in 1991, it was discovered that the specimen was missing and may have been stolen or sold.

The Haarlem Specimen (TM 6428/29, also known as the Teylers Specimen) was discovered in 1855 near Riedenburg, Germany, and described as a Pterodactylus crassipes in 1857 by Meyer. It was reclassified in 1970 by John Ostrom and is currently located at the Teylers Museum in Haarlem, the Netherlands. It was the very first specimen found, but was incorrectly classified at the time. It is also one of the least complete specimens, consisting mostly of limb bones, isolated cervical vertebrae, and ribs. In 2017 it was named as a separate genus Ostromia, considered more closely related to Anchiornis from China.

The Eichstätt Specimen (JM 2257) was discovered in 1951 near Workerszell, Germany, and described by Peter Wellnhofer in 1974. Currently located at the Jura Museum in Eichstätt, Germany, it is the smallest known specimen and has the second-best head. It is possibly a separate genus (Jurapteryx recurva) or species (A. recurva).

The Solnhofen Specimen (unnumbered specimen) was discovered in the 1970s near Eichstätt, Germany, and described in 1988 by Wellnhofer. Currently located at the Bürgermeister-Müller-Museum in Solnhofen, it originally was classified as Compsognathus by an amateur collector, the same mayor Friedrich Müller after which the museum is named. It is the largest specimen known and may belong to a separate genus and species, Wellnhoferia grandis. It is missing only portions of the neck, tail, backbone, and head.

The Munich Specimen (BSP 1999 I 50, formerly known as the Solenhofer-Aktien-Verein Specimen) was discovered on 3 August 1992 near Langenaltheim and described in 1993 by Wellnhofer. It is currently located at the Paläontologisches Museum München in Munich, to which it was sold in 1999 for 1.9 million Deutschmark. What was initially believed to be a bony sternum turned out to be part of the coracoid, but a cartilaginous sternum may have been present. Only the front of its face is missing. It has been used as the basis for a distinct species, A. bavarica, but more recent studies suggest it belongs to A. siemensii.

An eighth, fragmentary specimen was discovered in 1990 in the younger Mörnsheim Formation at Daiting, Suevia. Therefore, it is known as the Daiting Specimen, and had been known since 1996 only from a cast, briefly shown at the Naturkundemuseum in Bamberg. The original was purchased by palaeontologist Raimund Albertsdörfer in 2009. It was on display for the first time with six other original fossils of Archaeopteryx at the Munich Mineral Show in October 2009. The Daiting Specimen was subsequently named Archaeopteryx albersdoerferi by Kundrat et al. (2018). After a lengthy period in a closed private collection, it was moved to the Museum of Evolution at Knuthenborg Safaripark (Denmark) in 2022, where it has since been on display and also been made available for researchers.

Another fragmentary fossil was found in 2000. It is in private possession and, since 2004, on loan to the Bürgermeister-Müller Museum in Solnhofen, so it is called the Bürgermeister-Müller Specimen; the institute itself officially refers to it as the "Exemplar of the families Ottman & Steil, Solnhofen". As the fragment represents the remains of a single wing of Archaeopteryx, it is colloquially known as "chicken wing".

Long in a private collection in Switzerland, the Thermopolis Specimen (WDC CSG 100) was discovered in Bavaria and described in 2005 by Mayr, Pohl, and Peters. Donated to the Wyoming Dinosaur Center in Thermopolis, Wyoming, it has the best-preserved head and feet; most of the neck and the lower jaw have not been preserved. The "Thermopolis" specimen was described on 2 December 2005 Science journal article as "A well-preserved Archaeopteryx specimen with theropod features"; it shows that Archaeopteryx lacked a reversed toe—a universal feature of birds—limiting its ability to perch on branches and implying a terrestrial or trunk-climbing lifestyle. This has been interpreted as evidence of theropod ancestry. In 1988, Gregory S. Paul claimed to have found evidence of a hyperextensible second toe, but this was not verified and accepted by other scientists until the Thermopolis specimen was described. "Until now, the feature was thought to belong only to the species' close relatives, the deinonychosaurs." The Thermopolis Specimen was assigned to Archaeopteryx siemensii in 2007. The specimen is considered to represent the most complete and best-preserved Archaeopteryx remains yet.

The discovery of an eleventh specimen was announced in 2011; it was described in 2014. It is one of the more complete specimens, but is missing much of the skull and one forelimb. It is privately owned and has yet to be given a name. Palaeontologists of the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich studied the specimen, which revealed previously unknown features of the plumage, such as feathers on both the upper and lower legs and metatarsus, and the only preserved tail tip.

A twelfth specimen had been discovered by an amateur collector in 2010 at the Schamhaupten quarry, but the finding was only announced in February 2014. It was scientifically described in 2018. It represents a complete and mostly articulated skeleton with skull. It is the only specimen lacking preserved feathers. It is from the Painten Formation and somewhat older than the other specimens.

A thirteenth specimen, SMNK-PAL 10,000, was published in January 2025, this one from the Mörnsheim Formation. It preserves the right forelimb, shoulder, and fragments of the other limbs, with various features of the shoulder and forelimb resembling Archaeopteryx more than any other avialan within the Mörnsheim Formation. However, due to the fragmentary nature of this specimen, it cannot be assigned to a specific species within Archaeopteryx.

The existence of a fourteenth specimen (the Chicago specimen) was first informally announced in 2024 by the Field Museum in Chicago, US. One of two specimens in an institution outside Europe, the specimen was originally identified in a private collection in Switzerland, and had been acquired by these collectors in 1990, prior to Germany's 2015 ban on exporting Archaeopteryx specimens. The specimen was acquired by the Field Museum in 2022, and went on public display in 2024 following two years of preparation. In 2025, the paleornithologist Jingmai O'Connor and colleagues officially published a study describing this fourteenth specimen, reporting the first known tertials (specialized inner secondary flight feathers) and other novel features in Archaeopteryx.

Authenticity

Beginning in 1985, an amateur group including astronomer Fred Hoyle and physicist Lee Spetner, published a series of papers claiming that the feathers on the Berlin and London specimens of Archaeopteryx were forged. Their claims were repudiated by Alan J. Charig and others at the Natural History Museum in London. Most of their supposed evidence for a forgery was based on unfamiliarity with the processes of lithification; for example, they proposed that, based on the difference in texture associated with the feathers, feather impressions were applied to a thin layer of cement, without realizing that feathers themselves would have caused a textural difference. They also misinterpreted the fossils, claiming that the tail was forged as one large feather, when visibly this is not the case. In addition, they claimed that the other specimens of Archaeopteryx known at the time did not have feathers, which is incorrect; the Maxberg and Eichstätt specimens have obvious feathers.

They also expressed disbelief that slabs would split so smoothly, or that one half of a slab containing fossils would have good preservation, but not the counterslab. These are common properties of Solnhofen fossils, because the dead animals would fall onto hardened surfaces, which would form a natural plane for the future slabs to split along and would leave the bulk of the fossil on one side and little on the other.

Finally, the motives they suggested for a forgery are not strong, and are contradictory; one is that Richard Owen wanted to forge evidence in support of Charles Darwin's theory of evolution, which is unlikely given Owen's views toward Darwin and his theory. The other is that Owen wanted to set a trap for Darwin, hoping the latter would support the fossils so Owen could discredit him with the forgery; this is unlikely because Owen wrote a detailed paper on the London specimen, so such an action would certainly backfire.

Charig et al. pointed to the presence of hairline cracks in the slabs running through both rock and fossil impressions, and mineral growth over the slabs that had occurred before discovery and preparation, as evidence that the feathers were original. Spetner et al. then attempted to show that the cracks would have propagated naturally through their postulated cement layer, but neglected to account for the fact that the cracks were old and had been filled with calcite, and thus were not able to propagate. They also attempted to show the presence of cement on the London specimen through X-ray spectroscopy, and did find something that was not rock; it was not cement either, and is most probably a fragment of silicone rubber left behind when moulds were made of the specimen. Their suggestions have not been taken seriously by palaeontologists, as their evidence was largely based on misunderstandings of geology, and they never discussed the other feather-bearing specimens, which have increased in number since then. Charig et al. reported a discolouration: a dark band between two layers of limestone – they say it is the product of sedimentation. It is natural for limestone to take on the colour of its surroundings and most limestones are coloured (if not colour banded) to some degree, so the darkness was attributed to such impurities. They also mention that a complete absence of air bubbles in the rock slabs is further proof that the specimen is authentic.

Description

Most of the specimens of Archaeopteryx that have been discovered come from the Solnhofen limestone in Bavaria, southern Germany, which is a Lagerstätte, a rare and remarkable geological formation known for its superbly detailed fossils laid down during the early Tithonian stage of the Jurassic period, approximately 150.8–148.5 million years ago.

Archaeopteryx was roughly the size of a raven, with broad wings that were rounded at the ends and a long tail compared to its body length. It could reach up to 50 centimetres (1 ft 8 in) in body length and 70 centimetres (2 ft 4 in) in wingspan, with an estimated mass of 500 to 1,000 grams (18 to 35 oz). Archaeopteryx feathers, although less documented than its other features, were very similar in structure to modern-day bird feathers. Despite the presence of numerous avian features, Archaeopteryx had many non-avian theropod dinosaur characteristics. Unlike modern birds, Archaeopteryx had small teeth, as well as a long bony tail, features which Archaeopteryx shared with other dinosaurs of the time.

Because it displays features common to both birds and non-avian dinosaurs, Archaeopteryx has often been considered a link between them. In the 1970s, John Ostrom, following Thomas Henry Huxley's lead in 1868, argued that birds evolved within theropod dinosaurs and Archaeopteryx was a critical piece of evidence for this argument; it had several avian features, such as a wishbone, flight feathers, wings, and a partially reversed first toe along with dinosaur and theropod features. For instance, it has a long ascending process of the ankle bone, interdental plates, an obturator process of the ischium, and long chevrons in the tail. In particular, Ostrom found that Archaeopteryx was remarkably similar to the theropod family Dromaeosauridae.

Archaeopteryx had three separate digits on each fore-leg each ending with a "claw". Few birds have such features. Some birds, such as ducks, swans, Jacanas (Jacana sp.), and the hoatzin (Opisthocomus hoazin), have them concealed beneath their leg-feathers.

Plumage

Specimens of Archaeopteryx were most notable for their well-developed flight feathers. They were markedly asymmetrical and showed the structure of flight feathers in modern birds, with vanes given stability by a barb-barbule-barbicel arrangement. The tail feathers were less asymmetrical, again in line with the situation in modern birds and also had firm vanes. The thumb did not yet bear a separately movable tuft of stiff feathers.

The body plumage of Archaeopteryx is less well-documented and has only been properly researched in the well-preserved Berlin specimen. Thus, as more than one species seems to be involved, the research into the Berlin specimen's feathers does not necessarily hold true for the rest of the species of Archaeopteryx. In the Berlin specimen, there are "trousers" of well-developed feathers on the legs; some of these feathers seem to have a basic contour feather structure, but are somewhat decomposed (they lack barbicels as in ratites). In part they are firm and thus capable of supporting flight.

A patch of pennaceous feathers is found running along its back, which was quite similar to the contour feathers of the body plumage of modern birds in being symmetrical and firm, although not as stiff as the flight-related feathers. Apart from that, the feather traces in the Berlin specimen are limited to a sort of "proto-down" not dissimilar to that found in the dinosaur Sinosauropteryx: decomposed and fluffy, and possibly even appearing more like fur than feathers in life (although not in their microscopic structure). These occur on the remainder of the body—although some feathers did not fossilize and others were obliterated during preparation, leaving bare patches on specimens—and the lower neck.

There is no indication of feathering on the upper neck and head. While these conceivably may have been nude, this may still be an artefact of preservation. It appears that most Archaeopteryx specimens became embedded in anoxic sediment after drifting some time on their backs in the sea—the head, neck and the tail are generally bent downward, which suggests that the specimens had just started to rot when they were embedded, with tendons and muscle relaxing so that the characteristic shape (death pose) of the fossil specimens was achieved. This would mean that the skin already was softened and loose, which is bolstered by the fact that in some specimens the flight feathers were starting to detach at the point of embedding in the sediment. So it is hypothesized that the pertinent specimens moved along the sea bed in shallow water for some time before burial, the head and upper neck feathers sloughing off, while the more firmly attached tail feathers remained.

Colouration

In 2011, graduate student Ryan Carney and colleagues performed the first colour study on an Archaeopteryx specimen. Using scanning electron microscopy technology and energy-dispersive X-ray analysis, the team was able to detect the structure of melanosomes in the isolated feather specimen described in 1861. The resultant measurements were then compared to those of 87 modern bird species, and the original colour was calculated with a 95% likelihood to be black. The feather was determined to be black throughout, with heavier pigmentation in the distal tip. The feather studied was most probably a dorsal covert, which would have partly covered the primary feathers on the wings. The study does not mean that Archaeopteryx was entirely black, but suggests that it had some black colouration which included the coverts. Carney pointed out that this is consistent with what is known of modern flight characteristics, in that black melanosomes have structural properties that strengthen feathers for flight. In a 2013 study published in the Journal of Analytical Atomic Spectrometry, new analyses of Archaeopteryx's feathers revealed that the animal may have had complex light- and dark-coloured plumage, with heavier pigmentation in the distal tips and outer vanes. This analysis of colour distribution was based primarily on the distribution of sulphate within the fossil. An author on the previous Archaeopteryx colour study argued against the interpretation of such biomarkers as an indicator of eumelanin in the full Archaeopteryx specimen. Carney and other colleagues also argued against the 2013 study's interpretation of the sulphate and trace metals, and in a 2020 study published in Scientific Reports demonstrated that the isolated covert feather was entirely matte black (as opposed to black and white, or iridescent) and that the remaining "plumage patterns of Archaeopteryx remain unknown".

Classification

Today, fossils of the genus Archaeopteryx are usually assigned to one or two species, A. lithographica and A. siemensii, but their taxonomic history is complicated. Ten names have been published for the handful of specimens. As interpreted today, the name A. lithographica only referred to the single feather described by Meyer. In 1954 Gavin de Beer concluded that the London specimen was the holotype. In 1960, Swinton accordingly proposed that the name Archaeopteryx lithographica be placed on the official genera list making the alternative names Griphosaurus and Griphornis invalid. The ICZN, implicitly accepting De Beer's standpoint, did indeed suppress the plethora of alternative names initially proposed for the first skeleton specimens, which mainly resulted from the acrimonious dispute between Meyer and his opponent Johann Andreas Wagner (whose Griphosaurus problematicus—'problematic riddle-lizard'—was a vitriolic sneer at Meyer's Archaeopteryx). In addition, in 1977, the Commission ruled that the first species name of the Haarlem specimen, crassipes, described by Meyer as a pterosaur before its true nature was realized, was not to be given preference over lithographica in instances where scientists considered them to represent the same species.

It has been noted that the feather, the first specimen of Archaeopteryx described, does not correspond well with the flight-related feathers of Archaeopteryx. It certainly is a flight feather of a contemporary species, but its size and proportions indicate that it may belong to another, smaller species of feathered theropod, of which only this feather is known so far. As the feather had been designated the type specimen, the name Archaeopteryx should then no longer be applied to the skeletons, thus creating significant nomenclatorial confusion. In 2007, two sets of scientists therefore petitioned the ICZN requesting that the London specimen explicitly be made the type by designating it as the new holotype specimen, or neotype. This suggestion was upheld by the ICZN after four years of debate, and the London specimen was designated the neotype on 3 October 2011.

Below is a cladogram published in 2013 by Godefroit et al.

| Avialae |

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Species

It has been argued that all the specimens belong to the same species, A. lithographica. Differences do exist among the specimens, and while some researchers regard these as due to the different ages of the specimens, some may be related to actual species diversity. In particular, the Munich, Eichstätt, Solnhofen, and Thermopolis specimens differ from the London, Berlin, and Haarlem specimens in being smaller or much larger, having different finger proportions, having more slender snouts lined with forward-pointing teeth, and the possible presence of a sternum. Due to these differences, most individual specimens have been given their own species name at one point or another. The Berlin specimen has been designated as Archaeornis siemensii, the Eichstätt specimen as Jurapteryx recurva, the Munich specimen as Archaeopteryx bavarica, and the Solnhofen specimen as Wellnhoferia grandis.

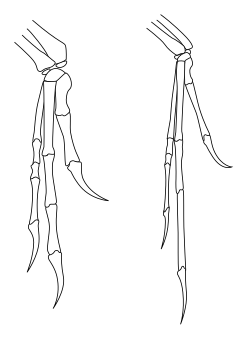

In 2007, a review of all well-preserved specimens including the then-newly discovered Thermopolis specimen concluded that two distinct species of Archaeopteryx could be supported: A. lithographica (consisting of at least the London and Solnhofen specimens), and A. siemensii (consisting of at least the Berlin, Munich, and Thermopolis specimens). The two species are distinguished primarily by large flexor tubercles on the foot claws in A. lithographica (the claws of A. siemensii specimens being relatively simple and straight). A. lithographica also had a constricted portion of the crown in some teeth and a stouter metatarsus. A supposed additional species, Wellnhoferia grandis (based on the Solnhofen specimen), seems to be indistinguishable from A. lithographica except in its larger size.[24]

Synonyms

If two names are given, the first denotes the original describer of the "species", the second the author on whom the given name combination is based. As always in zoological nomenclature, putting an author's name in parentheses denotes that the taxon was originally described in a different genus.

- Archaeopteryx lithographica Meyer, 1861 [conserved name]

- Archaeopterix lithographica Anon., 1861 [lapsus]

- Griphosaurus problematicus Wagner, 1862 [rejected name 1961 per ICZN Opinion 607]

- Griphornis longicaudatus Owen vide Woodward, 1862 [rejected name 1961 per ICZN Opinion 607]

- Archaeopteryx macrura Owen, 1862 [rejected name 1961 per ICZN Opinion 607]

- Archaeopteryx oweni Petronievics, 1917 [rejected name 1961 per ICZN Opinion 607]

- Archaeopteryx recurva Howgate, 1984

- Jurapteryx recurva (Howgate, 1984) Howgate, 1985

- Wellnhoferia grandis Elżanowski, 2001

- Archaeopteryx siemensii Dames, 1897

- Archaeornis siemensii (Dames, 1897) Petronievics, 1917

- Archaeopteryx bavarica Wellnhofer, 1993

"Archaeopteryx" vicensensis (Anon. fide Lambrecht, 1933) is a nomen nudum for what appears to be an undescribed pterosaur.

Phylogenetic position

Modern palaeontology has often classified Archaeopteryx as the most primitive bird. However, it is not thought to be a true ancestor of modern birds, but rather a close relative of that ancestor. Nonetheless, Archaeopteryx was often used as a model of the true ancestral bird. Several authors have done so. Lowe (1935) and Thulborn (1984) questioned whether Archaeopteryx truly was the first bird. They suggested that Archaeopteryx was a dinosaur that was no more closely related to birds than were other dinosaur groups. Kurzanov (1987) suggested that Avimimus was more likely to be the ancestor of all birds than Archaeopteryx. Barsbold (1983) and Zweers and Van den Berge (1997) noted that many maniraptoran lineages are extremely birdlike, and they suggested that different groups of birds may have descended from different dinosaur ancestors.

The discovery of the closely related Xiaotingia in 2011 led to new phylogenetic analyses that suggested that Archaeopteryx is a deinonychosaur rather than an avialan, and therefore, not a "bird" under most common uses of that term.[2] A more thorough analysis was published soon after to test this hypothesis, and failed to arrive at the same result; it found Archaeopteryx in its traditional position at the base of Avialae, while Xiaotingia was recovered as a basal dromaeosaurid or troodontid. The authors of the follow-up study noted that uncertainties still exist, and that it may not be possible to state confidently whether or not Archaeopteryx is a member of Avialae or not, barring new and better specimens of relevant species.

Phylogenetic studies conducted by Senter, et al. (2012) and Turner, Makovicky, and Norell (2012) also found Archaeopteryx to be more closely related to living birds than to dromaeosaurids and troodontids. On the other hand, Godefroit et al. (2013) recovered Archaeopteryx as more closely related to dromaeosaurids and troodontids in the analysis included in their description of Eosinopteryx brevipenna. The authors used a modified version of the matrix from the study describing Xiaotingia, adding Jinfengopteryx elegans and Eosinopteryx brevipenna to it, as well as adding four additional characters related to the development of the plumage. Unlike the analysis from the description of Xiaotingia, the analysis conducted by Godefroit, et al. did not find Archaeopteryx to be related particularly closely to Anchiornis and Xiaotingia, which were recovered as basal troodontids instead.

Agnolín and Novas (2013) found Archaeopteryx and (possibly synonymous) Wellnhoferia to form a clade sister to the lineage including Jeholornis and Pygostylia, with Microraptoria, Unenlagiinae, and the clade containing Anchiornis and Xiaotingia being successively closer outgroups to the Avialae (defined by the authors as the clade stemming from the last common ancestor of Archaeopteryx and Aves). Another phylogenetic study by Godefroit, et al., using a more inclusive matrix than the one from the analysis in the description of Eosinopteryx brevipenna, also found Archaeopteryx to be a member of Avialae (defined by the authors as the most inclusive clade containing Passer domesticus, but not Dromaeosaurus albertensis or Troodon formosus). Archaeopteryx was found to form a grade at the base of Avialae with Xiaotingia, Anchiornis, and Aurornis. Compared to Archaeopteryx, Xiaotingia was found to be more closely related to extant birds, while both Anchiornis and Aurornis were found to be more distantly so.

Hu et al. (2018), Wang et al. (2018) and Hartman et al. (2019) found Archaeopteryx to have been a deinonychosaur instead of an avialan. More specifically, it and closely related taxa were considered basal deinonychosaurs, with dromaeosaurids and troodontids forming together a parallel lineage within the group. Because Hartman et al. found Archaeopteryx isolated in a group of flightless deinonychosaurs (otherwise considered "anchiornithids"), they considered it highly probable that this animal evolved flight independently from bird ancestors (and from Microraptor and Yi).

The authors, however, found that the Archaeopteryx being an avialan was only slightly less likely than this hypothesis, and as likely as Archaeopterygidae and Troodontidae being sister clades.

Palaeobiology

Flight

As in the wings of modern birds, the flight feathers of Archaeopteryx were somewhat asymmetrical and the tail feathers were rather broad. This implies that the wings and tail were used for lift generation, but it is unclear whether Archaeopteryx was capable of flapping flight or simply a glider. The lack of a bony breastbone suggests that Archaeopteryx was not a very strong flier, but flight muscles might have attached to the thick, boomerang-shaped wishbone, the platelike coracoids, or perhaps, to a cartilaginous sternum. The sideways orientation of the glenoid (shoulder) joint between scapula, coracoid, and humerus—instead of the dorsally angled arrangement found in modern birds—may indicate that Archaeopteryx was unable to lift its wings above its back, a requirement for the upstroke found in modern flapping flight. According to a study by Philip Senter in 2006, Archaeopteryx was indeed unable to use flapping flight as modern birds do, but it may well have used a downstroke-only flap-assisted gliding technique. However, a more recent study solves this issue by suggesting a different flight stroke configuration for non-avian flying theropods.

Archaeopteryx wings were relatively large, which would have resulted in a low stall speed and reduced turning radius. The short and rounded shape of the wings would have increased drag, but also could have improved its ability to fly through cluttered environments such as trees and brush (similar wing shapes are seen in birds that fly through trees and brush, such as crows and pheasants). The presence of "hind wings", asymmetrical flight feathers stemming from the legs similar to those seen in dromaeosaurids such as Microraptor, also would have added to the aerial mobility of Archaeopteryx. The first detailed study of the hind wings by Longrich in 2006, suggested that the structures formed up to 12% of the total airfoil. This would have reduced stall speed by up to 6% and turning radius by up to 12%.

The feathers of Archaeopteryx were asymmetrical. This has been interpreted as evidence that it was a flyer, because flightless birds tend to have symmetrical feathers. Some scientists, including Thomson and Speakman, have questioned this. They studied more than 70 families of living birds, and found that some flightless types do have a range of asymmetry in their feathers, and that the feathers of Archaeopteryx fall into this range. The degree of asymmetry seen in Archaeopteryx is more typical for slow flyers than for flightless birds.

In 2010, Robert L. Nudds and Gareth J. Dyke in the journal Science published a paper in which they analysed the rachises of the primary feathers of Confuciusornis and Archaeopteryx. The analysis suggested that the rachises on these two genera were thinner and weaker than those of modern birds relative to body mass. The authors determined that Archaeopteryx and Confuciusornis, were unable to use flapping flight. This study was criticized by Philip J. Currie and Luis Chiappe. Chiappe suggested that it is difficult to measure the rachises of fossilized feathers, and Currie speculated that Archaeopteryx and Confuciusornis must have been able to fly to some degree, as their fossils are preserved in what is believed to have been marine or lake sediments, suggesting that they must have been able to fly over deep water. Gregory Paul also disagreed with the study, arguing in a 2010 response that Nudds and Dyke had overestimated the masses of these early birds, and that more accurate mass estimates allowed powered flight even with relatively narrow rachises. Nudds and Dyke had assumed a mass of 250 g (8.8 oz) for the Munich specimen Archaeopteryx, a young juvenile, based on published mass estimates of larger specimens. Paul argued that a more reasonable body mass estimate for the Munich specimen is about 140 g (4.9 oz). Paul also criticized the measurements of the rachises themselves, noting that the feathers in the Munich specimen are poorly preserved. Nudds and Dyke reported a diameter of 0.75 mm (0.03 in) for the longest primary feather, which Paul could not confirm using photographs. Paul measured some of the inner primary feathers, finding rachises 1.25–1.4 mm (0.049–0.055 in) across. Despite these criticisms, Nudds and Dyke stood by their original conclusions. They claimed that Paul's statement, that an adult Archaeopteryx would have been a better flyer than the juvenile Munich specimen, was dubious. This, they reasoned, would require an even thicker rachis, evidence for which has not yet been presented. Another possibility is that they had not achieved true flight, but instead used their wings as aids for extra lift while running over water after the fashion of the basilisk lizard, which could explain their presence in lake and marine deposits (see Origin of avian flight).

In 2004, scientists analysing a detailed CT scan of the braincase of the London Archaeopteryx concluded that its brain was significantly larger than that of most dinosaurs, indicating that it possessed the brain size necessary for flying. The overall brain anatomy was reconstructed using the scan. The reconstruction showed that the regions associated with vision took up nearly one-third of the brain. Other well-developed areas involved hearing and muscle coordination. The skull scan also revealed the structure of its inner ear. The structure more closely resembles that of modern birds than the inner ear of non-avian reptiles. These characteristics taken together suggest that Archaeopteryx had the keen sense of hearing, balance, spatial perception, and coordination needed to fly. Archaeopteryx had a cerebrum-to-brain-volume ratio 78% of the way to modern birds from the condition of non-coelurosaurian dinosaurs such as Carcharodontosaurus or Allosaurus, which had a crocodile-like anatomy of the brain and inner ear. Newer research shows that while the Archaeopteryx brain was more complex than that of more primitive theropods, it had a more generalized brain volume among Maniraptora dinosaurs, even smaller than that of other non-avian dinosaurs in several instances, which indicates the neurological development required for flight was already a common trait in the maniraptoran clade.

Recent studies of flight feather barb geometry reveal that modern birds possess a larger barb angle in the trailing vane of the feather, whereas Archaeopteryx lacks this large barb angle, indicating potentially weak flight abilities.

Archaeopteryx continues to play an important part in scientific debates about the origin and evolution of birds. Some scientists see it as a semi-arboreal climbing animal, following the idea that birds evolved from tree-dwelling gliders (the "trees down" hypothesis for the evolution of flight proposed by O. C. Marsh). Other scientists see Archaeopteryx as running quickly along the ground, supporting the idea that birds evolved flight by running (the "ground up" hypothesis proposed by Samuel Wendell Williston). Still others suggest that Archaeopteryx might have been at home both in the trees and on the ground, like modern crows, and this latter view is what currently is considered best supported by morphological characters. Altogether, it appears that the species was not particularly specialized for running on the ground or for perching. A scenario outlined by Elżanowski in 2002 suggested that Archaeopteryx used its wings mainly to escape predators by glides punctuated with shallow downstrokes to reach successively higher perches, and alternatively, to cover longer distances (mainly) by gliding down from cliffs or treetops.

In March 2018, scientists reported that Archaeopteryx was likely capable of a flight stroke cycle morphologically closer to the grabbing motion of maniraptorans and distinct from that of modern birds. This study on Archaeopteryx's bone histology identified biomechanical and physiological adaptations exhibited by modern volant birds that perform intermittent flapping, such as pheasants and other burst flyers.

Some researchers suggested that the feather sheaths of Archaeopteryx shows a center-out, flight related moulting strategy like modern birds. As it was a weak flier, this would have been extremely advantageous in preserving its maximum flight performance. Kiat and colleagues reinterpreted this purported moulting evidence to be problematic and equivocal at best, and considered that these structures more likely represents the calami traces of the fully grown feathers, though the original authors still remained by their conclusion.

Growth

An histological study by Erickson, Norell, Zhongue, and others in 2009 estimated that Archaeopteryx grew relatively slowly compared to modern birds, presumably because the outermost portions of Archaeopteryx bones appear poorly vascularized; in living vertebrates, poorly vascularized bone is correlated with slow growth rate. They also assume that all known skeletons of Archaeopteryx come from juvenile specimens. Because the bones of Archaeopteryx could not be histologically sectioned in a formal skeletochronological (growth ring) analysis, Erickson and colleagues used bone vascularity (porosity) to estimate bone growth rate. They assumed that poorly vascularized bone grows at similar rates in all birds and in Archaeopteryx. The poorly vascularized bone of Archaeopteryx might have grown as slowly as that in a mallard (2.5 micrometres per day) or as fast as that in an ostrich (4.2 micrometres per day). Using this range of bone growth rates, they calculated how long it would take to "grow" each specimen of Archaeopteryx to the observed size; it may have taken at least 970 days (there were 375 days in a Late Jurassic year) to reach an adult size of 0.8–1 kg (1.8–2.2 lb). The study also found that the avialans Jeholornis and Sapeornis grew relatively slowly, as did the dromaeosaurid Mahakala. The avialans Confuciusornis and Ichthyornis grew relatively quickly, following a growth trend similar to that of modern birds. One of the few modern birds that exhibit slow growth is the flightless kiwi, and the authors speculated that Archaeopteryx and the kiwi had similar basal metabolic rate.

Daily activity patterns

Comparisons between the scleral rings of Archaeopteryx and modern birds and reptiles indicate that it may have been diurnal, similar to most modern birds.

Palaeoecology

The richness and diversity of the Solnhofen limestones in which all specimens of Archaeopteryx have been found have shed light on an ancient Jurassic Bavaria strikingly different from the present day. The latitude was similar to Florida, though the climate was likely to have been drier, as evidenced by fossils of plants with adaptations for arid conditions and a lack of terrestrial sediments characteristic of rivers. Evidence of plants, although scarce, include cycads and conifers while animals found include a large number of insects, small lizards, pterosaurs, and Compsognathus.

The excellent preservation of Archaeopteryx fossils and other terrestrial fossils found at Solnhofen indicates that they did not travel far before becoming preserved. The Archaeopteryx specimens found were therefore likely to have lived on the low islands surrounding the Solnhofen lagoon rather than to have been corpses that drifted in from farther away. Archaeopteryx skeletons are considerably less numerous in the deposits of Solnhofen than those of pterosaurs, of which seven genera have been found. The pterosaurs included species such as Rhamphorhynchus belonging to the Rhamphorhynchidae, the group which dominated the ecological niche currently occupied by seabirds, and which became extinct at the end of the Jurassic. The pterosaurs, which also included Pterodactylus, were common enough that it is unlikely that the specimens found are vagrants from the larger islands 50 km (31 mi) to the north.

The islands that surrounded the Solnhofen lagoon were low lying, semi-arid, and sub-tropical with a long dry season and little rain. The closest modern analogue for the Solnhofen conditions is said to be Orca Basin in the northern Gulf of Mexico, although it is much deeper than the Solnhofen lagoons. The flora of these islands was adapted to these dry conditions and consisted mostly of low (3 m [10 ft]) shrubs. Contrary to reconstructions of Archaeopteryx climbing large trees, these seem to have been mostly absent from the islands; few trunks have been found in the sediments and fossilized tree pollen also is absent.

The lifestyle of Archaeopteryx is difficult to reconstruct and there are several theories regarding it. Some researchers suggest that it was primarily adapted to life on the ground, while other researchers suggest that it was principally arboreal on the basis of the curvature of the claws which has since been questioned. The absence of trees does not preclude Archaeopteryx from an arboreal lifestyle, as several species of bird live exclusively in low shrubs. Various aspects of the morphology of Archaeopteryx point to either an arboreal or ground existence, including the length of its legs and the elongation in its feet; some authorities consider it likely to have been a generalist capable of feeding in both shrubs and open ground, as well as along the shores of the lagoon. It most likely hunted small prey, seizing it with its jaws if it was small enough, or with its claws if it was larger.