Pressure

exerted by particle collisions inside a closed container. The

collisions that exert the pressure are highlighted in red. | |

Common symbols | p, P |

| SI unit | pascal (Pa) |

| In SI base units | kg⋅m−1⋅s−2 |

Derivations from other quantities | p = F / A |

| Dimension | |

| Thermodynamics |

|---|

|

Pressure (symbol: p or P) is the force applied perpendicular to the surface of an object per unit area over which that force is distributed. Gauge pressure (also spelled gage pressure) is the pressure relative to the ambient pressure.

Various units are used to express pressure. Some of these derive from a unit of force divided by a unit of area; the SI unit of pressure, the pascal (Pa), for example, is one newton per square metre (N/m2); similarly, the pound-force per square inch (psi, symbol lbf/in2) is the traditional unit of pressure in the imperial and US customary systems. Pressure may also be expressed in terms of standard atmospheric pressure; the unit atmosphere (atm) is equal to this pressure, and the torr is defined as 1⁄760 of this. Manometric units such as the centimetre of water, millimetre of mercury, and inch of mercury are used to express pressures in terms of the height of column of a particular fluid in a manometer.

Definition

Pressure is the amount of force applied perpendicular to the surface of an object per unit area. The symbol for it is "p" or P. The IUPAC recommendation for pressure is a lower-case p. However, upper-case P is widely used. The usage of P vs p depends upon the field in which one is working, on the nearby presence of other symbols for quantities such as power and momentum, and on writing style.

Formula

|

Conjugate variables of thermodynamics | ||||||||

|

Mathematically: where:

- is the pressure,

- is the magnitude of the normal force,

- is the area of the surface on contact.

Pressure is a scalar quantity. It relates the vector area element (a vector normal to the surface) with the normal force acting on it. The pressure is the scalar proportionality constant that relates these two normal vectors:

The minus sign comes from the convention that the force is considered towards the surface element, while the normal vector points outward. The equation has meaning in that, for any surface S in contact with the fluid, the total force exerted by the fluid on that surface is the surface integral over S of the right-hand side of the above equation.

It is incorrect (although rather usual) to say "the pressure is directed in such or such direction". The pressure, as a scalar, has no direction. The force given by the previous relationship to the quantity has a direction, but the pressure does not. If we change the orientation of the surface element, the direction of the normal force changes accordingly, but the pressure remains the same.

Pressure is distributed to solid boundaries or across arbitrary sections of fluid normal to these boundaries or sections at every point. It is a fundamental parameter in thermodynamics, and it is conjugate to volume. It is defined as a derivative of the internal energy of a system:

where:

- is the internal energy,

- is the volume of the system,

- The subscripts mean that the derivative is taken at fixed entropy () and particle number ().

Units

The SI unit for pressure is the pascal (Pa), equal to one newton per square metre (N/m2, or kg·m−1·s−2). This name for the unit was added in 1971; before that, pressure in SI was expressed in newtons per square metre.

Other units of pressure, such as pounds per square inch (lbf/in2) and bar, are also in common use. The CGS unit of pressure is the barye (Ba), equal to 1 dyn·cm−2, or 0.1 Pa. Pressure is sometimes expressed in grams-force or kilograms-force per square centimetre ("g/cm2" or "kg/cm2") and the like without properly identifying the force units. But using the names kilogram, gram, kilogram-force, or gram-force (or their symbols) as units of force is deprecated in SI. The technical atmosphere (symbol: at) is 1 kgf/cm2 (98.0665 kPa, or 14.223 psi).

Pressure is related to energy density and may be expressed in units such as joules per cubic metre (J/m3, which is equal to Pa). Mathematically:

Some meteorologists prefer the hectopascal (hPa) for atmospheric air pressure, which is equivalent to the older unit millibar (mbar). Similar pressures are given in kilopascals (kPa) in most other fields, except aviation where the hecto- prefix is commonly used. The inch of mercury is still used in the United States. Oceanographers usually measure underwater pressure in decibars (dbar) because pressure in the ocean increases by approximately one decibar per metre depth.

The standard atmosphere (atm) is an established constant. It is approximately equal to typical air pressure at Earth mean sea level and is defined as 101325 Pa (IUPAC recommends the value 100000 Pa, but prior to 1982 the value 101325 Pa (= 1 atm) was usually used).

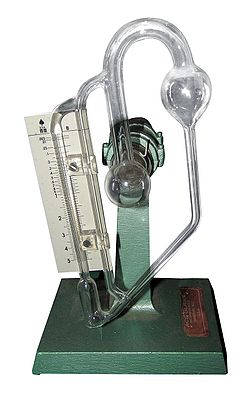

Because pressure is commonly measured by its ability to displace a column of liquid in a manometer, pressures are often expressed as a depth of a particular fluid (e.g., centimetres of water, millimetres of mercury or inches of mercury). The most common choices are mercury (Hg) and water; water is nontoxic and readily available, while mercury's high density allows a shorter column (and so a smaller manometer) to be used to measure a given pressure. The pressure exerted by a column of liquid of height h and density ρ is given by the hydrostatic pressure equation p = ρgh, where g is the gravitational acceleration. Fluid density and local gravity can vary from one reading to another depending on local factors, so the height of a fluid column does not define pressure precisely.

When millimetres of mercury (or inches of mercury) are quoted today, these units are not based on a physical column of mercury; rather, they have been given precise definitions that can be expressed in terms of SI units. One millimetre of mercury is approximately equal to one torr. The water-based units still depend on the density of water, a measured, rather than defined, quantity. These manometric units are still encountered in many fields. Blood pressure is measured in millimetres (or centimetres) of mercury in most of the world, and lung pressures in centimetres of water are still common.

Underwater divers use the metre sea water (msw or MSW) and foot sea water (fsw or FSW) units of pressure, and these are the units for pressure gauges used to measure pressure exposure in diving chambers and personal decompression computers. A msw is defined as 0.1 bar (= 10,000 Pa), is not the same as a linear metre of depth. 33.066 fsw = 1 atm (1 atm = 101,325 Pa / 33.066 = 3,064.326 Pa). The pressure conversion from msw to fsw is different from the length conversion: 10 msw = 32.6336 fsw, while 10 m = 32.8083 ft.

Gauge pressure is often given in units with "g" appended, e.g. "kPag", "barg" or "psig", and units for measurements of absolute pressure are sometimes given a suffix of "a", to avoid confusion, for example "kPaa", "psia". However, the US National Institute of Standards and Technology recommends that, to avoid confusion, any modifiers be instead applied to the quantity being measured rather than the unit of measure. For example, "pg = 100 psi" rather than "p = 100 psig".

Differential pressure is expressed in units with "d" appended; this type of measurement is useful when considering sealing performance or whether a valve will open or close.

Presently or formerly popular pressure units include the following:

- atmosphere (atm)

- manometric units:

- centimetre, inch, millimetre (torr) and micrometre (mTorr, micron) of mercury,

- height of equivalent column of water, including millimetre (mm H

2O), centimetre (cm H

2O), metre, inch, and foot of water;

- imperial and customary units:

- kip, short ton-force, long ton-force, pound-force, ounce-force, and poundal per square inch,

- short ton-force and long ton-force per square inch,

- fsw (feet sea water) used in underwater diving, particularly in connection with diving pressure exposure and decompression;

- non-SI metric units:

- bar, decibar, millibar,

- msw (metres sea water), used in underwater diving, particularly in connection with diving pressure exposure and decompression,

- kilogram-force, or kilopond, per square centimetre (technical atmosphere),

- gram-force and tonne-force (metric ton-force) per square centimetre,

- barye (dyne per square centimetre),

- kilogram-force and tonne-force per square metre,

- sthene per square metre (pieze).

- bar, decibar, millibar,

Examples

As an example of varying pressures, a finger can be pressed against a wall without making any lasting impression; however, the same finger pushing a thumbtack can easily damage the wall. Although the force applied to the surface is the same, the thumbtack applies more pressure because the point concentrates that force into a smaller area. Pressure is transmitted to solid boundaries or across arbitrary sections of fluid normal to these boundaries or sections at every point. Unlike stress, pressure is defined as a scalar quantity. The negative gradient of pressure is called the force density.

Another example is a knife. If the flat edge is used, force is distributed over a larger surface area resulting in less pressure, and it will not cut. Whereas using the sharp edge, which has less surface area, results in greater pressure, and so the knife cuts smoothly. This is one example of a practical application of pressure.

For gases, pressure is sometimes measured not as an absolute pressure, but relative to atmospheric pressure; such measurements are called gauge pressure. An example of this is the air pressure in an automobile tire, which might be said to be "220 kPa (32 psi)", but is actually 220 kPa (32 psi) above atmospheric pressure. Since atmospheric pressure at sea level is about 100 kPa (14.7 psi), the absolute pressure in the tire is therefore about 320 kPa (46 psi). In technical work, this is written "a gauge pressure of 220 kPa (32 psi)".

Where space is limited, such as on pressure gauges, name plates, graph labels, and table headings, the use of a modifier in parentheses, such as "kPa (gauge)" or "kPa (absolute)", is permitted. In non-SI technical work, a gauge pressure of 32 psi (220 kPa) is sometimes written as "32 psig", and an absolute pressure as "32 psia", though the other methods explained above that avoid attaching characters to the unit of pressure are preferred.

Gauge pressure is the relevant measure of pressure wherever one is interested in the stress on storage vessels and the plumbing components of fluidics systems. However, whenever equation-of-state properties, such as densities or changes in densities, must be calculated, pressures must be expressed in terms of their absolute values. For instance, if the atmospheric pressure is 100 kPa (15 psi), a gas (such as helium) at 200 kPa (29 psi) (gauge) (300 kPa or 44 psi [absolute]) is 50% denser than the same gas at 100 kPa (15 psi) (gauge) (200 kPa or 29 psi [absolute]). Focusing on gauge values, one might erroneously conclude the first sample had twice the density of the second one.[citation needed]

Scalar nature

In a static gas, the gas as a whole does not appear to move. The individual molecules of the gas, however, are in constant random motion. Because there are an extremely large number of molecules and because the motion of the individual molecules is random in every direction, no motion is detected. When the gas is at least partially confined (that is, not free to expand rapidly), the gas will exhibit a hydrostatic pressure. This confinement can be achieved with either a physical container, or in the gravitational well of a large mass, such as a planet, otherwise known as atmospheric pressure.

In the case of planetary atmospheres, the pressure-gradient force of the gas pushing outwards from higher pressure, lower altitudes to lower pressure, higher altitudes is balanced by the gravitational force, preventing the gas from diffusing into outer space and maintaining hydrostatic equilibrium.

In a physical container, the pressure of the gas originates from the molecules colliding with the walls of the container. The walls of the container can be anywhere inside the gas, and the force per unit area (the pressure) is the same. If the "container" is shrunk down to a very small point (becoming less true as the atomic scale is approached), the pressure will still have a single value at that point. Therefore, pressure is a scalar quantity, not a vector quantity. It has magnitude but no direction sense associated with it. Pressure force acts in all directions at a point inside a gas. At the surface of a gas, the pressure force acts perpendicular (at right angle) to the surface.

A closely related quantity is the stress tensor σ, which relates the vector force to the vector area via the linear relation .

This tensor may be expressed as the sum of the viscous stress tensor minus the hydrostatic pressure. The negative of the stress tensor is sometimes called the pressure tensor, but in the following, the term "pressure" will refer only to the scalar pressure.

According to the theory of general relativity, pressure increases the strength of a gravitational field (see stress–energy tensor) and so adds to the mass-energy cause of gravity. This effect is unnoticeable at everyday pressures but is significant in neutron stars, although it has not been experimentally tested.

Types

Fluid pressure

Fluid pressure is most often the compressive stress at some point within a fluid. (The term fluid refers to both liquids and gases – for more information specifically about liquid pressure, see section below.)

Fluid pressure occurs in one of two situations:

- An open condition, called "open channel flow", e.g. the ocean, a swimming pool, or the atmosphere.

- A closed condition, called "closed conduit", e.g. a water line or gas line.

Pressure in open conditions usually can be approximated as the pressure in "static" or non-moving conditions (even in the ocean where there are waves and currents), because the motions create only negligible changes in the pressure. Such conditions conform with principles of fluid statics. The pressure at any given point of a non-moving (static) fluid is called the hydrostatic pressure.

Closed bodies of fluid are either "static", when the fluid is not moving, or "dynamic", when the fluid can move as in either a pipe or by compressing an air gap in a closed container. The pressure in closed conditions conforms with the principles of fluid dynamics.

The concepts of fluid pressure are predominantly attributed to the discoveries of Blaise Pascal and Daniel Bernoulli. Bernoulli's equation can be used in almost any situation to determine the pressure at any point in a fluid. The equation makes some assumptions about the fluid, such as the fluid being ideal and incompressible. An ideal fluid is a fluid in which there is no friction, it is inviscid (zero viscosity). The equation for all points of a system filled with a constant-density fluid is

where:

- p, pressure of the fluid,

- = ρg, density × acceleration of gravity is the (volume-) specific weight of the fluid,

- v, velocity of the fluid,

- g, acceleration of gravity,

- z, elevation,

- , pressure head,

- , velocity head.

Applications

- Hydraulic brakes

- Artesian well

- Blood pressure

- Hydraulic head

- Plant cell turgidity

- Pythagorean cup

- Pressure washing

Explosion or deflagration pressures

Explosion or deflagration pressures are the result of the ignition of explosive gases, mists, dust/air suspensions, in unconfined and confined spaces.

Negative pressures

While pressures are, in general, positive, there are several situations in which negative pressures may be encountered:

- When dealing in relative (gauge) pressures. For instance, an absolute pressure of 80 kPa may be described as a gauge pressure of −21 kPa (i.e., 21 kPa below an atmospheric pressure of 101 kPa). For example, abdominal decompression is an obstetric procedure during which negative gauge pressure is applied intermittently to a pregnant woman's abdomen.

- Negative absolute pressures are possible. They are effectively tension, and both bulk solids and bulk liquids can be put under negative absolute pressure by pulling on them. Microscopically, the molecules in solids and liquids have attractive interactions that overpower the thermal kinetic energy, so some tension can be sustained. Thermodynamically, however, a bulk material under negative pressure is in a metastable state, and it is especially fragile in the case of liquids where the negative pressure state is similar to superheating and is easily susceptible to cavitation. In certain situations, the cavitation can be avoided and negative pressures sustained indefinitely, for example, liquid mercury has been observed to sustain up to −425 atm in clean glass containers. Negative liquid pressures are thought to be involved in the ascent of sap in plants taller than 10 m (the atmospheric pressure head of water).

- The Casimir effect can create a small attractive force due to interactions with vacuum energy; this force is sometimes termed "vacuum pressure" (not to be confused with the negative gauge pressure of a vacuum).

- For non-isotropic stresses in rigid bodies, depending on how the

orientation of a surface is chosen, the same distribution of forces may

have a component of positive stress along one surface normal,

with a component of negative stress acting along another surface

normal. The pressure is then defined as the average of the three

principal stresses.

- The stresses in an electromagnetic field are generally non-isotropic, with the stress normal to one surface element (the normal stress) being negative, and positive for surface elements perpendicular to this.

- In cosmology, dark energy creates a very small yet cosmically significant amount of negative pressure, which accelerates the expansion of the universe.

Stagnation pressure

Stagnation pressure is the pressure a fluid exerts when it is forced to stop moving. Consequently, although a fluid moving at higher speed will have a lower static pressure, it may have a higher stagnation pressure when forced to a standstill. Static pressure and stagnation pressure are related by: where

- is the stagnation pressure,

- is the density,

- is the flow velocity,

- is the static pressure.

The pressure of a moving fluid can be measured using a Pitot tube, or one of its variations such as a Kiel probe or Cobra probe, connected to a manometer. Depending on where the inlet holes are located on the probe, it can measure static pressures or stagnation pressures.

Surface pressure and surface tension

There is a two-dimensional analog of pressure – the lateral force per unit length applied on a line perpendicular to the force.

Surface pressure is denoted by π: and shares many similar properties with three-dimensional pressure. Properties of surface chemicals can be investigated by measuring pressure/area isotherms, as the two-dimensional analog of Boyle's law, πA = k, at constant temperature.

Surface tension is another example of surface pressure, but with a reversed sign, because "tension" is the opposite to "pressure".

Pressure of an ideal gas

In an ideal gas, molecules have no volume and do not interact. According to the ideal gas law, pressure varies linearly with temperature and quantity, and inversely with volume: where:

- p is the absolute pressure of the gas,

- n is the amount of substance,

- T is the absolute temperature,

- V is the volume,

- R is the ideal gas constant.

Real gases exhibit a more complex dependence on the variables of state.

Vapour pressure

Vapour pressure is the pressure of a vapour in thermodynamic equilibrium with its condensed phases in a closed system. All liquids and solids have a tendency to evaporate into a gaseous form, and all gases have a tendency to condense back to their liquid or solid form.

The atmospheric pressure boiling point of a liquid (also known as the normal boiling point) is the temperature at which the vapor pressure equals the ambient atmospheric pressure. With any incremental increase in that temperature, the vapor pressure becomes sufficient to overcome atmospheric pressure and lift the liquid to form vapour bubbles inside the bulk of the substance. Bubble formation deeper in the liquid requires a higher pressure, and therefore higher temperature, because the fluid pressure increases above the atmospheric pressure as the depth increases.

The vapor pressure that a single component in a mixture contributes to the total pressure in the system is called partial vapor pressure.

Liquid pressure

When a person swims under the water, water pressure is felt acting on the person's eardrums. The deeper that person swims, the greater the pressure. The pressure felt is due to the weight of the water above the person. As someone swims deeper, there is more water above the person and therefore greater pressure. The pressure a liquid exerts depends on its depth.

Liquid pressure also depends on the density of the liquid. If someone was submerged in a liquid more dense than water, the pressure would be correspondingly greater. Thus, we can say that the depth, density and liquid pressure are directly proportionate. The pressure due to a liquid in liquid columns of constant density and gravity at a depth within a substance is represented by the following formula: where:

- p is liquid pressure,

- g is gravity at the surface of overlaying material,

- ρ is density of liquid,

- h is height of liquid column or depth within a substance.

Another way of saying the same formula is the following:

| Derivation of this equation |

|---|

|

The pressure a liquid exerts against the sides and bottom of a container depends on the density and the depth of the liquid. If atmospheric pressure is neglected, liquid pressure against the bottom is twice as great at twice the depth; at three times the depth, the liquid pressure is threefold; etc. Or, if the liquid is two or three times as dense, the liquid pressure is correspondingly two or three times as great for any given depth. Liquids are practically incompressible – that is, their volume can hardly be changed by pressure (water volume decreases by only 50 millionths of its original volume for each atmospheric increase in pressure). Thus, except for small changes produced by temperature, the density of a particular liquid is practically the same at all depths.

Atmospheric pressure pressing on the surface of a liquid must be taken into account when trying to discover the total pressure acting on a liquid. The total pressure of a liquid, then, is ρgh plus the pressure of the atmosphere. When this distinction is important, the term total pressure is used. Otherwise, discussions of liquid pressure refer to pressure without regard to the normally ever-present atmospheric pressure.

The pressure does not depend on the amount of liquid present. Volume is not the important factor – depth is. The average water pressure acting against a dam depends on the average depth of the water and not on the volume of water held back. For example, a wide but shallow lake with a depth of 3 m (10 ft) exerts only half the average pressure that a small 6 m (20 ft) deep pond does. (The total force applied to the longer dam will be greater, due to the greater total surface area for the pressure to act upon. But for a given 5-foot (1.5 m)-wide section of each dam, the 10 ft (3.0 m) deep water will apply one quarter the force of 20 ft (6.1 m) deep water). A person will feel the same pressure whether their head is dunked a metre beneath the surface of the water in a small pool or to the same depth in the middle of a large lake.

If four interconnected vases contain different amounts of water but are all filled to equal depths, then a fish with its head dunked a few centimetres under the surface will be acted on by water pressure that is the same in any of the vases. If the fish swims a few centimetres deeper, the pressure on the fish will increase with depth and be the same no matter which vase the fish is in. If the fish swims to the bottom, the pressure will be greater, but it makes no difference which vase it is in. All vases are filled to equal depths, so the water pressure is the same at the bottom of each vase, regardless of its shape or volume. If water pressure at the bottom of a vase were greater than water pressure at the bottom of a neighboring vase, the greater pressure would force water sideways and then up the neighboring vase to a higher level until the pressures at the bottom were equalized. Pressure is depth dependent, not volume dependent, so there is a reason that water seeks its own level.

Restating this as an energy equation, the energy per unit volume in an ideal, incompressible liquid is constant throughout its vessel. At the surface of a stationary liquid in a vessel gravitational potential energy is large but liquid pressure is low. At the bottom of the vessel, all the gravitational potential energy is converted to pressure. The two energy components change linearly with the depth so the sum of pressure and gravitational potential energy per unit volume is constant throughout the volume of the fluid. The units of pressure are equivalent to energy per unit volume. (In the SI system of units, the pascal is equivalent to the joule per cubic metre.) Mathematically, it is described by Bernoulli's equation, where velocity head is zero and comparisons per unit volume in the vessel are

Terms have the same meaning as in section Fluid pressure.

Direction of liquid pressure

An experimentally determined fact about liquid pressure is that it is exerted equally in all directions. If someone is submerged in water, no matter which way that person tilts their head, the person will feel the same amount of water pressure on their ears. Because a liquid can flow, this pressure is not only downward. Pressure is seen acting sideways when water spurts sideways from a leak in the side of an upright can. Pressure also acts upward, as demonstrated when someone tries to push a beach ball beneath the surface of the water. The bottom of a ball is pushed upward by water pressure (buoyancy).

When a liquid presses against a surface, there is a net force that is perpendicular to the surface. Although pressure does not have a specific direction, force does. A submerged triangular block has water forced against each point from many directions, but components of the force that are not perpendicular to the surface cancel each other out, leaving only a net perpendicular point. This is why liquid particles' velocity only alters in a normal component after they are collided to the container's wall. Likewise, if the collision site is a hole, water spurting from the hole in a bucket initially exits the bucket in a direction at right angles to the surface of the bucket in which the hole is located. Then it curves downward due to gravity. If there are three holes in a bucket (top, bottom, and middle), then the force vectors perpendicular to the inner container surface will increase with increasing depth – that is, a greater pressure at the bottom makes it so that the bottom hole will shoot water out the farthest. The force exerted by a fluid on a smooth surface is always at right angles to the surface. The speed of liquid out of the hole is , where h is the depth below the free surface.[25] As predicted by Torricelli's law this is the same speed the water (or anything else) would have if freely falling the same vertical distance h.

Kinematic pressure

is the kinematic pressure, where is the pressure and constant mass density. The SI unit of P is m2/s2. Kinematic pressure is used in the same manner as kinematic viscosity in order to compute the Navier–Stokes equation without explicitly showing the density .

Navier–Stokes equation with kinematic quantities