Spacecraft propulsion is any method used to accelerate spacecraft and artificial satellites. In-space propulsion exclusively deals with propulsion systems used in the vacuum of space and should not be confused with space launch or atmospheric entry.

Several methods of pragmatic spacecraft propulsion have been developed, each having its own drawbacks and advantages. Most satellites have simple reliable chemical thrusters (often monopropellant rockets) or resistojet rockets for orbital station-keeping, while a few use momentum wheels for attitude control. Russian and antecedent Soviet bloc satellites have used electric propulsion for decades, and newer Western geo-orbiting spacecraft are starting to use them for north–south station-keeping and orbit raising. Interplanetary vehicles mostly use chemical rockets as well, although a few have used electric propulsion such as ion thrusters and Hall-effect thrusters. Various technologies need to support everything from small satellites and robotic deep space exploration to space stations and human missions to Mars.

Hypothetical in-space propulsion technologies describe propulsion technologies that could meet future space science and exploration needs. These propulsion technologies are intended to provide effective exploration of the Solar System and may permit mission designers to plan missions to "fly anytime, anywhere, and complete a host of science objectives at the destinations" and with greater reliability and safety. With a wide range of possible missions and candidate propulsion technologies, the question of which technologies are "best" for future missions is a difficult one; expert opinion now holds that a portfolio of propulsion technologies should be developed to provide optimum solutions for a diverse set of missions and destinations.

Purpose and function

The primary goals of Space exploration are to reach the destination safely, quickly, with a large quantity of payload mass, and relatively inexpensively. The act of reaching the destination requires an in-space propulsion system, and the other metrics are modifiers to this fundamental action. Propulsion technologies can significantly improve a number of critical aspects of the mission.

When launching a spacecraft from Earth, a propulsion method must overcome a higher gravitational pull to provide a positive net acceleration. When in space, the purpose of a propulsion system is to change the velocity, or v, of a spacecraft, in order to establish the desired trajectory.

In-space propulsion begins where the upper stage of the launch vehicle leaves off, performing the functions of primary propulsion, reaction control, station keeping, precision pointing, and orbital maneuvering. The main engines used in space provide the primary propulsive force for orbit transfer, planetary trajectories, and extra planetary landing and ascent. The reaction control and orbital maneuvering systems provide the propulsive force for orbit maintenance, position control, station keeping, and spacecraft attitude control.

In orbit, any additional impulse, even tiny, will result in a change in the orbit path, in two ways:

- Prograde/retrograde (i.e. acceleration in the tangential/opposite in tangential direction), which increases/decreases altitude of orbit.

- Perpendicular to orbital plane, which changes orbital inclination.

Earth's surface is situated fairly deep in a gravity well; the escape velocity required to leave its orbit is 11.2 kilometers/second. Thus for destinations beyond, propulsion systems need enough propellant and to be of high enough efficiency. The same is true for other planets and moons, albeit some have lower gravity wells.

As human beings evolved in a gravitational field of "one g" (9.81m/s²), it would be most comfortable for a human spaceflight propulsion system to provide that acceleration continuously, (though human bodies can tolerate much larger accelerations over short periods). The occupants of a rocket or spaceship having such a propulsion system would be free from the ill effects of free fall, such as nausea, muscular weakness, reduced sense of taste, or leaching of calcium from their bones.

Theory

The Tsiolkovsky rocket equation shows, using the law of conservation of momentum, that for a rocket engine propulsion method to change the momentum of a spacecraft, it must change the momentum of something else in the opposite direction. In other words, the rocket must exhaust mass opposite the spacecraft's acceleration direction, with such exhausted mass called propellant or reaction mass. For this to happen, both reaction mass and energy are needed. The impulse provided by launching a particle of reaction mass with mass m at velocity v is mv. But this particle has kinetic energy mv²/2, which must come from somewhere. In a conventional solid, liquid, or hybrid rocket, fuel is burned, providing the energy, and the reaction products are allowed to flow out of the engine nozzle, providing the reaction mass. In an ion thruster, electricity is used to accelerate ions behind the spacecraft. Here other sources must provide the electrical energy (e.g. a solar panel or a nuclear reactor), whereas the ions provide the reaction mass.

The rate of change of velocity is called acceleration and the rate of change of momentum is called force. To reach a given velocity, one can apply a small acceleration over a long period of time, or a large acceleration over a short time; similarly, one can achieve a given impulse with a large force over a short time or a small force over a long time. This means that for maneuvering in space, a propulsion method that produces tiny accelerations for a long time can often produce the same impulse as another which produces large accelerations for a short time. However, when launching from a planet, tiny accelerations cannot overcome the planet's gravitational pull and so cannot be used.

Some designs however, operate without internal reaction mass by taking advantage of magnetic fields or light pressure to change the spacecraft's momentum.

Efficiency

When discussing the efficiency of a propulsion system, designers often focus on the effective use of the reaction mass, which must be carried along with the rocket and is irretrievably consumed when used. Spacecraft performance can be quantified in amount of change in momentum per unit of propellant consumed, also called specific impulse. This is a measure of the amount of impulse that can be obtained from a fixed amount of reaction mass. The higher the specific impulse, the better the efficiency. Ion propulsion engines have high specific impulse (~3000 s) and low thrust whereas chemical rockets like monopropellant or bipropellant rocket engines have a low specific impulse (~300 s) but high thrust.

The impulse per unit weight-on-Earth (typically designated by ) has units of seconds. Because the weight on Earth of the reaction mass is often unimportant when discussing vehicles in space, specific impulse can also be discussed in terms of impulse per unit mass, with the same units as velocity (e.g., meters per second). This measure is equivalent to the effective exhaust velocity of the engine, and is typically designated . Either the change in momentum per unit of propellant used by a spacecraft, or the velocity of the propellant exiting the spacecraft, can be used to measure its "specific impulse." The two values differ by a factor of the standard acceleration due to gravity, gn, 9.80665 m/s² ().

In contrast to chemical rockets, electrodynamic rockets use electric or magnetic fields to accelerate a charged propellant. The benefit of this method is that it can achieve exhaust velocities, and therefore , more than 10 times greater than those of a chemical engine, producing steady thrust with far less fuel. With a conventional chemical propulsion system, 2% of a rocket's total mass might make it to the destination, with the other 98% having been consumed as fuel. With an electric propulsion system, 70% of what's aboard in low Earth orbit can make it to a deep-space destination.

However, there is a trade-off. Chemical rockets transform propellants into most of the energy needed to propel them, but their electromagnetic equivalents must carry or produce the power required to create and accelerate propellants. Because there are currently practical limits on the amount of power available on a spacecraft, these engines are not suitable for launch vehicles or when a spacecraft needs a quick, large impulse, such as when it brakes to enter a capture orbit. Even so, because electrodynamic rockets offer very high , mission planners are increasingly willing to sacrifice power and thrust (and the extra time it will take to get a spacecraft where it needs to go) in order to save large amounts of propellant mass.

Operating domains

Spacecraft operate in many areas of space. These include orbital maneuvering, interplanetary travel, and interstellar travel.

Orbital

Artificial satellites are first launched into the desired altitude by conventional liquid/solid propelled rockets, after which the satellite may use onboard propulsion systems for orbital stationkeeping. Once in the desired orbit, they often need some form of attitude control so that they are correctly pointed with respect to the Earth, the Sun, and possibly some astronomical object of interest. They are also subject to drag from the thin atmosphere, so that to stay in orbit for a long period of time some form of propulsion is occasionally necessary to make small corrections (orbital station-keeping). Many satellites need to be moved from one orbit to another from time to time, and this also requires propulsion. A satellite's useful life is usually over once it has exhausted its ability to adjust its orbit.

Interplanetary

For interplanetary travel, a spacecraft can use its engines to leave Earth's orbit. It is not explicitly necessary as the initial boost given by the rocket, gravity slingshot, monopropellant/bipropellent attitude control propulsion system are enough for the exploration of the solar system (see New Horizons). Once it has done so, it must make its way to its destination. Current interplanetary spacecraft do this with a series of short-term trajectory adjustments. In between these adjustments, the spacecraft typically moves along its trajectory without accelerating. The most fuel-efficient means to move from one circular orbit to another is with a Hohmann transfer orbit: the spacecraft begins in a roughly circular orbit around the Sun. A short period of thrust in the direction of motion accelerates or decelerates the spacecraft into an elliptical orbit around the Sun which is tangential to its previous orbit and also to the orbit of its destination. The spacecraft falls freely along this elliptical orbit until it reaches its destination, where another short period of thrust accelerates or decelerates it to match the orbit of its destination. Special methods such as aerobraking or aerocapture are sometimes used for this final orbital adjustment.

Some spacecraft propulsion methods such as solar sails provide very low but inexhaustible thrust; an interplanetary vehicle using one of these methods would follow a rather different trajectory, either constantly thrusting against its direction of motion in order to decrease its distance from the Sun, or constantly thrusting along its direction of motion to increase its distance from the Sun. The concept has been successfully tested by the Japanese IKAROS solar sail spacecraft.

Interstellar

Because interstellar distances are great, a tremendous velocity is needed to get a spacecraft to its destination in a reasonable amount of time. Acquiring such a velocity on launch and getting rid of it on arrival remains a formidable challenge for spacecraft designers. No spacecraft capable of short duration (compared to human lifetime) interstellar travel has yet been built, but many hypothetical designs have been discussed.

Propulsion technology

Spacecraft propulsion technology can be of several types, such as chemical, electric or nuclear. They are distinguished based on the physics of the propulsion system and how thrust is generated. Other experimental and more theoretical types are also included, depending on their technical maturity. Additionally, there may be credible meritorious in-space propulsion concepts not foreseen or reviewed at the time of publication, and which may be shown to be beneficial to future mission applications.

Almost all types are reaction engines, which produce thrust by expelling reaction mass, in accordance with Newton's third law of motion. Examples include jet engines, rocket engines, pump-jet, and more uncommon variations such as Hall–effect thrusters, ion drives, mass drivers, and nuclear pulse propulsion.

Chemical propulsion

A large fraction of rocket engines in use today are chemical rockets; that is, they obtain the energy needed to generate thrust by chemical reactions to create a hot gas that is expanded to produce thrust. Many different propellant combinations are used to obtain these chemical reactions, including, for example, hydrazine, liquid oxygen, liquid hydrogen, nitrous oxide, and hydrogen peroxide. They can be used as a monopropellant or in bi-propellant configurations.

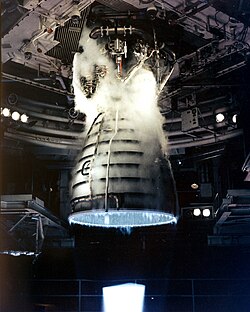

Rocket engines provide essentially the highest specific powers and high specific thrusts of any engine used for spacecraft propulsion. Most rocket engines are internal combustion heat engines (although non-combusting forms exist). Rocket engines generally produce a high-temperature reaction mass, as a hot gas, which is achieved by combusting a solid, liquid or gaseous fuel with an oxidiser within a combustion chamber. The extremely hot gas is then allowed to escape through a high-expansion ratio bell-shaped nozzle, a feature that gives a rocket engine its characteristic shape. The effect of the nozzle is to accelerate the mass, converting most of the thermal energy into kinetic energy, where exhaust speeds reaching as high as 10 times the speed of sound at sea level are common.

Green chemical propulsion

The dominant form of chemical propulsion for satellites has historically been hydrazine, however, this fuel is highly toxic and at risk of being banned across Europe. Non-toxic 'green' alternatives are now being developed to replace hydrazine. Nitrous oxide-based alternatives are garnering traction and government support, with development being led by commercial companies Dawn Aerospace, Impulse Space, and Launcher. The first nitrous oxide-based system flown in space was by D-Orbit onboard their ION Satellite Carrier (space tug) in 2021, using six Dawn Aerospace B20 thrusters, launched upon a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket.

Electric propulsion

Rather than relying on high temperature and fluid dynamics to accelerate the reaction mass to high speeds, there are a variety of methods that use electrostatic or electromagnetic forces to accelerate the reaction mass directly, where the reaction mass is usually a stream of ions.

Ion propulsion rockets typically heat a plasma or charged gas inside a magnetic bottle and release it via a magnetic nozzle so that no solid matter needs to come in contact with the plasma. Such an engine uses electric power, first to ionize atoms, and then to create a voltage gradient to accelerate the ions to high exhaust velocities. For these drives, at the highest exhaust speeds, energetic efficiency and thrust are all inversely proportional to exhaust velocity. Their very high exhaust velocity means they require huge amounts of energy and thus with practical power sources provide low thrust, but use hardly any fuel.

Electric propulsion is commonly used for station keeping on commercial communications satellites and for prime propulsion on some scientific space missions because of their high specific impulse. However, they generally have very small values of thrust and therefore must be operated for long durations to provide the total impulse required by a mission.

The idea of electric propulsion dates to 1906, when Robert Goddard considered the possibility in his personal notebook. Konstantin Tsiolkovsky published the idea in 1911.

Electric propulsion methods include:

- Ion thrusters, which accelerate ions first and later neutralize the ion beam with an electron stream emitted from a cathode called a neutralizer;

- Electrothermal thrusters, wherein electromagnetic fields are used to generate a plasma to increase the heat of the bulk propellant, the thermal energy imparted to the propellant gas is then converted into kinetic energy by a nozzle of either physical material construction or by magnetic means;

- Arcjets using DC current or microwaves

- Helicon double-layer thrusters

- Resistojets

- Electromagnetic thrusters, wherein ions are accelerated either by the Lorentz Force or by the effect of electromagnetic fields where the electric field is not in the direction of the acceleration;

- Mass drivers designed for propulsion.

Power sources

For some missions, particularly reasonably close to the Sun, solar energy may be sufficient, and has often been used, but for others further out or at higher power, nuclear energy is necessary; engines drawing their power from a nuclear source are called nuclear electric rockets.

Current nuclear power generators are approximately half the weight of solar panels per watt of energy supplied, at terrestrial distances from the Sun. Chemical power generators are not used due to the far lower total available energy. Beamed power to the spacecraft is considered to have potential, according to NASA and the University of Colorado Boulder.

With any current source of electrical power, chemical, nuclear or solar, the maximum amount of power that can be generated limits the amount of thrust that can be produced to a small value.[citation needed] Power generation adds significant mass to the spacecraft, and ultimately the weight of the power source limits the performance of the vehicle.

Nuclear propulsion

Nuclear fuels typically have very high specific energy, much higher than chemical fuels, which means that they can generate large amounts of energy per unit mass. This makes them valuable in spaceflight, as it can enable high specific impulses, sometimes even at high thrusts. The machinery to do this is complex, but research has developed methods for their use in propulsion systems, and some have been tested in a laboratory.

Here, nuclear propulsion moreso refers to the source of propulsion being nuclear, instead of a nuclear electric rocket where a nuclear reactor would provide power (instead of solar panels) for other types of electrical propulsion.

Nuclear propulsion methods include:

- Fission-fragment rockets

- Fission sails

- Fusion rockets

- Nuclear thermal rockets (NTR)

- Nuclear pulse propulsion

- Nuclear salt-water rockets

- Radioisotope rockets

Field propulsion without internal reaction mass

There are several different space drives that need little or no reaction mass to function. Field propulsion refers to propulsion systems in which thrust arises from interactions with external fields or ambient media, rather than from the sustained expulsion of onboard reaction mass or reliance on solid chemical fuels.

EM wave-based propulsion

The law of conservation of momentum is usually taken to imply that any engine which uses no reaction mass cannot accelerate the center of mass of a spaceship (changing orientation, on the other hand, is possible).[citation needed] But space is not empty, especially space inside the Solar System; there are gravitation fields, magnetic fields, electromagnetic waves, solar wind and solar radiation. Electromagnetic waves in particular are known to contain momentum, despite being massless; specifically the momentum flux density P of an EM wave is quantitatively 1/c2 times the Poynting vector S, i.e. P = S/c2, where c is the velocity of light.[citation needed]

Solar and magnetic sails

The concept of solar sails rely on radiation pressure from electromagnetic energy, but they require a large collection surface to function effectively. E-sails propose to use very thin and lightweight wires holding an electric charge to deflect particles, which may have more controllable directionality.

Magnetic sails deflect charged particles from the solar wind with a magnetic field, thereby imparting momentum to the spacecraft. For instance, the so-called Magsail is a large superconducting loop proposed for acceleration/deceleration in the solar wind and deceleration in the Interstellar medium. A variant is the mini-magnetospheric plasma propulsion system and its successor, the magnetoplasma sail, which inject plasma at a low rate to enhance the magnetic field to more effectively deflect charged particles in a plasma wind.

Japan launched a solar sail-powered spacecraft, IKAROS in May 2010, which successfully demonstrated propulsion and guidance (and is still active as of this date). As further proof of the solar sail concept, NanoSail-D became the first such powered satellite to orbit Earth. As of August 2017, NASA confirmed the Sunjammer solar sail project was concluded in 2014 with lessons learned for future space sail projects. The U.K. Cubesail programme will be the first mission to demonstrate solar sailing in low Earth orbit, and the first mission to demonstrate full three-axis attitude control of a solar sail.

Other

The concept of a gravitational slingshot is a form of propulsion to carry a space probe onward to other destinations without the expense of reaction mass; harnessing the gravitational energy of other celestial objects allows the spacecraft to gain kinetic energy. However, more energy can be obtained from the gravity assist if rockets are used via the Oberth effect.

A tether propulsion system employs a long cable with a high tensile strength to change a spacecraft's orbit, such as by interaction with a planet's magnetic field or through momentum exchange with another object.

Beam-powered propulsion is another method of propulsion without reaction mass, and includes sails pushed by laser, microwave, or particle beams.

Other propulsion types

Many spacecraft use reaction wheels or control moment gyroscopes to control orientation in space. A satellite or other space vehicle is subject to the law of conservation of angular momentum, which constrains a body from a net change in angular velocity. Thus, for a vehicle to change its relative orientation without expending reaction mass, another part of the vehicle may rotate in the opposite direction. Non-conservative external forces, primarily gravitational and atmospheric, can contribute up to several degrees per day to angular momentum, so such systems are designed to "bleed off" undesired rotational energies built up over time.

Advanced propulsion technology

Advanced, and in some cases theoretical, propulsion technologies may use chemical or nonchemical physics to produce thrust but are generally considered to be of lower technical maturity with challenges that have not been overcome. For both human and robotic exploration, traversing the solar system is a struggle against time and distance. The most distant planets are 4.5–6 billion kilometers from the Sun and to reach them in any reasonable time requires much more capable propulsion systems than conventional chemical rockets. Rapid inner solar system missions with flexible launch dates are difficult, requiring propulsion systems that are beyond today's current state of the art. The logistics, and therefore the total system mass required to support sustained human exploration beyond Earth to destinations such as the Moon, Mars, or near-Earth objects, are daunting unless more efficient in-space propulsion technologies are developed and fielded.

A variety of hypothetical propulsion techniques have been considered that require a deeper understanding of the properties of space, particularly inertial frames and the vacuum state. Such methods are highly speculative and include:

A NASA assessment of its Breakthrough Propulsion Physics Program divides such proposals into those that are non-viable for propulsion purposes, those that are of uncertain potential, and those that are not impossible according to current theories.

Table of methods

Below is a summary of some of the more popular, proven technologies, followed by increasingly speculative methods. Four numbers are shown. The first is the effective exhaust velocity: the equivalent speed which the propellant leaves the vehicle. This is not necessarily the most important characteristic of the propulsion method; thrust and power consumption and other factors can be. However,

- if the delta-v is much more than the exhaust velocity, then exorbitant amounts of fuel are necessary (see the section on calculations, above), and

- if it is much more than the delta-v, then, proportionally more energy is needed; if the power is limited, as with solar energy, this means that the journey takes a proportionally longer time.

The second and third are the typical amounts of thrust and the typical burn times of the method; outside a gravitational potential, small amounts of thrust applied over a long period will give the same effect as large amounts of thrust over a short period, if the object is not significantly influenced by gravity. The fourth is the maximum delta-v the technique can give without staging. For rocket-like propulsion systems, this is a function of mass fraction and exhaust velocity; mass fraction for rocket-like systems is usually limited by propulsion system weight and tankage weight.For a system to achieve this limit, the payload may need to be a negligible percentage of the vehicle, and so the practical limit on some systems can be much lower.

| Method | Effective exhaust velocity (km/s) |

Thrust (N) | Firing duration |

Maximum delta-v (km/s) |

Technology readiness level |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solid-fuel rocket | <2.5 | <107 | Minutes | 7 | 9: Flight proven |

| Hybrid rocket | <4 | Minutes | >3 | 9: Flight proven | |

| Monopropellant rocket | 1–3 | 0.1–400 | Milliseconds–minutes | 3 | 9: Flight proven |

| Liquid-fuel rocket | <4.4 | <107 | Minutes | 9 | 9: Flight proven |

| Electrostatic ion thruster | 15–210 | Months–years | >100 | 9: Flight proven | |

| Hall-effect thruster (HET) | up to 50 | Months–years | >100 | 9: Flight proven | |

| Resistojet rocket | 2–6 | 10−2–10 | Minutes | ? | 8: Flight qualified |

| Arcjet rocket | 4–16 | 10−2–10 | Minutes | ? | 8: Flight qualified |

| Field-emission electric propulsion (FEEP) |

100–130 | 10−6–10−3 | Months–years | ? | 8: Flight qualified |

| Pulsed plasma thruster (PPT) | 20 | 0.1 | 80–400 days | ? | 7: Prototype demonstrated in space |

| Dual-mode propulsion rocket | 1–4.7 | 0.1–107 | Milliseconds–minutes | 3–9 | 7: Prototype demonstrated in space |

| Solar sails | 299,792.458, Speed of light | 9.08/km2 at 1 AU 908/km2 at 0.1 AU 10−10/km2 at 4 ly |

Indefinite | >40 |

|

| Tripropellant rocket | 2.5–5.3 | 0.1–107 | Minutes | 9 | 6: Prototype demonstrated on ground |

| Magnetoplasmadynamic thruster (MPD) |

20–100 | 100 | Weeks | ? | 6: Model, 1 kW demonstrated in space |

| Nuclear–thermal rocket | 9 | 107 | Minutes | >20 | 6: Prototype demonstrated on ground |

| Propulsive mass drivers | 0–30 | 104–108 | Months | ? | 6: Model, 32 MJ demonstrated on ground |

| Tether propulsion | — | 1–1012 | Minutes | 7 | 6: Model, 31.7 km demonstrated in space |

| Air-augmented rocket | 5–6 | 0.1–107 | Seconds–minutes | >7? | 6: Prototype demonstrated on ground |

| Liquid-air-cycle engine | 4.5 | 103–107 | Seconds–minutes | ? | 6: Prototype demonstrated on ground |

| Pulsed-inductive thruster (PIT) | 10–80 | 20 | Months | ? | 5: Component validated in vacuum |

| Variable-specific-impulse magnetoplasma rocket (VASIMR) |

10–300 | 40–1,200 | Days–months | >100 | 5: Component, 200 kW validated in vacuum |

| Magnetic-field oscillating amplified thruster (MOA) |

10–390 | 0.1–1 | Days–months | >100 | 5: Component validated in vacuum |

| Solar–thermal rocket | 7–12 | 1–100 | Weeks | >20 | 4: Component validated in lab |

| Radioisotope rocket/Steam thruster | 7–8 | 1.3–1.5 | Months | ? | 4: Component validated in lab |

| Nuclear–electric rocket | As electric propulsion method used | 4: Component, 400 kW validated in lab | |||

| Orion Project (near-term nuclear pulse propulsion) |

20–100 | 109–1012 | Days | 30–60 | 3: Validated, 900 kg proof-of-concept |

| Space elevator | — | — | Indefinite | >12 | 3: Validated proof-of-concept |

| Reaction Engines SABRE[106] | 30/4.5 | 0.1 – 107 | Minutes | 9.4 | 3: Validated proof-of-concept |

| Electric sails | 145–750, solar wind | ? | Indefinite | >40 | 3: Validated proof-of-concept |

| Magsail in Solar wind | — | 644 | Indefinite | 250–750 | 3: Validated proof-of-concept |

| Magnetoplasma sail in Solar wind | 278 | 700 | Months–Years | 250–750 | 4: Component validated in lab |

| Magsail in Interstellar medium | — | 88,000 initially | Decades | 15,000 | 3: Validated proof-of-concept |

| Beam-powered/laser | As propulsion method powered by beam | 3: Validated, 71 m proof-of-concept | |||

| Launch loop/orbital ring | — | 104 | Minutes | 11–30 | 2: Technology concept formulated |

| Nuclear pulse propulsion (Project Daedalus' drive) |

20–1,000 | 109–1012 | Years | 15,000 | 2: Technology concept formulated |

| Gas-core reactor rocket | 10 – 20 | 103–106 | ? | ? | 2: Technology concept formulated |

| Nuclear salt-water rocket | 100 | 103–107 | Half-hour | ? | 2: Technology concept formulated |

| Fission sail | ? | ? | ? | ? | 2: Technology concept formulated |

| Fission-fragment rocket | 15,000 | ? | ? | ? | 2: Technology concept formulated |

| Nuclear–photonic rocket/Photon rocket | 299,792.458, Speed of light | 10−5–1 | Years–decades | ? | 2: Technology concept formulated |

| Fusion rocket | 100–1,000 | ? | ? | ? | 2: Technology concept formulated |

| Antimatter-catalyzed nuclear pulse propulsion |

200–4,000 | ? | Days–weeks | ? | 2: Technology concept formulated |

| Antimatter rocket | 10,000–100,000 | ? | ? | ? | 2: Technology concept formulated |

| Bussard ramjet | 2.2–20,000 | ? | Indefinite | 30,000 | 2: Technology concept formulated |

| Method | Effective exhaust velocity (km/s) |

Thrust (N) | Firing duration |

Maximum delta-v (km/s) |

Technology readiness level |

Table Notes

- Divided by 3.1 correction factor.

Planetary and atmospheric propulsion

Launch-assist mechanisms

There have been many ideas proposed for launch-assist mechanisms that have the potential of substantially reducing the cost of getting to orbit. Proposed non-rocket spacelaunch launch-assist mechanisms include:

- Skyhook (requires reusable suborbital launch vehicle, not feasible using presently available materials)

- Space elevator (tether from Earth's surface to geostationary orbit, cannot be built with existing materials)

- Launch loop (a very fast enclosed rotating loop about 80 km tall)

- Space fountain (a very tall building held up by a stream of masses fired from its base)

- Orbital ring (a ring around Earth with spokes hanging down off bearings)

- Electromagnetic catapult (railgun, coilgun) (an electric gun)

- Rocket sled launch

- Space gun (Project HARP, ram accelerator) (a chemically powered gun)

- Beam-powered propulsion rockets and jets powered from the ground via a beam

- High-altitude platforms to assist initial stage

Air-breathing engines

Studies generally show that conventional air-breathing engines, such as ramjets or turbojets are basically too heavy (have too low a thrust/weight ratio) to give significant performance improvement when installed on a launch vehicle. However, launch vehicles can be air launched from separate lift vehicles (e.g. B-29, Pegasus Rocket and White Knight) which do use such propulsion systems. Jet engines mounted on a launch rail could also be so used.

On the other hand, very lightweight or very high-speed engines have been proposed that take advantage of the air during ascent:

- SABRE – a lightweight hydrogen fuelled turbojet with precooler

- ATREX – a lightweight hydrogen fuelled turbojet with precooler

- Liquid air cycle engine – a hydrogen-fuelled jet engine that liquifies the air before burning it in a rocket engine

- Scramjet – jet engines that use supersonic combustion

- Shcramjet – similar to a scramjet engine, however it takes advantage of shockwaves produced from the aircraft in the combustion chamber to assist in increasing overall efficiency.

Normal rocket launch vehicles fly almost vertically before rolling over at an altitude of some tens of kilometers before burning sideways for orbit; this initial vertical climb wastes propellant but is optimal as it greatly reduces airdrag. Airbreathing engines burn propellant much more efficiently and this would permit a far flatter launch trajectory. The vehicles would typically fly approximately tangentially to Earth's surface until leaving the atmosphere then perform a rocket burn to bridge the final delta-v to orbital velocity.

For spacecraft already in very low-orbit, air-breathing electric propulsion could use residual gases in the upper atmosphere as a propellant. Air-breathing electric propulsion could make a new class of long-lived, low-orbiting missions feasible on Earth, Mars or Venus.

Planetary arrival and landing

When a vehicle is to enter orbit around its destination planet, or when it is to land, it must adjust its velocity. This can be done using any of the methods listed above (provided they can generate a high enough thrust), but there are methods that can take advantage of planetary atmospheres and/or surfaces.

- Aerobraking allows a spacecraft to reduce the high point of an elliptical orbit by repeated brushes with the atmosphere at the low point of the orbit. This can save a considerable amount of fuel because it takes much less delta-V to enter an elliptical orbit compared to a low circular orbit. Because the braking is done over the course of many orbits, heating is comparatively minor, and a heat shield is not required. This has been done on several Mars missions such as Mars Global Surveyor, 2001 Mars Odyssey, and Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, and at least one Venus mission, Magellan.

- Aerocapture is a much more aggressive manoeuver, converting an incoming hyperbolic orbit to an elliptical orbit in one pass. This requires a heat shield and more controlled navigation because it must be completed in one pass through the atmosphere, and unlike aerobraking no preview of the atmosphere is possible. If the intent is to remain in orbit, then at least one more propulsive maneuver is required after aerocapture—otherwise the low point of the resulting orbit will remain in the atmosphere, resulting in eventual re-entry. Aerocapture has not yet been tried on a planetary mission, but the re-entry skip by Zond 6 and Zond 7 upon lunar return were aerocapture maneuvers, because they turned a hyperbolic orbit into an elliptical orbit. On these missions, because there was no attempt to raise the perigee after the aerocapture, the resulting orbit still intersected the atmosphere, and re-entry occurred at the next perigee.

- A ballute is an inflatable drag device.

- Parachutes can land a probe on a planet or moon with an atmosphere, usually after the atmosphere has scrubbed off most of the velocity, using a heat shield.

- Airbags can soften the final landing.

- Lithobraking, or stopping by impacting the surface, is usually done by accident. However, it may be done deliberately with the probe expected to survive (see, for example, the Deep Impact spacecraft), in which case very sturdy probes are required.

Research

Development of technologies will result in technical solutions that improve thrust levels, specific impulse, power, specific mass, (or specific power), volume, system mass, system complexity, operational complexity, commonality with other spacecraft systems, manufacturability, durability, and cost. These types of improvements will yield decreased transit times, increased payload mass, safer spacecraft, and decreased costs. In some instances, the development of technologies within this technology area will result in mission-enabling breakthroughs that will revolutionize space exploration. There is no single propulsion technology that will benefit all missions or mission types; the requirements for in-space propulsion vary widely according to their intended application.

One institution focused on developing primary propulsion technologies aimed at benefitting near- and mid-term science missions by reducing cost, mass, and/or travel times is the Glenn Research Center (GRC). Electric propulsion architectures are of particular interest to the GRC, including ion and Hall thrusters. One system combines solar sails, a form of propellantless propulsion which relies on naturally occurring starlight for propulsion energy, and Hall thrusters. Other propulsion technologies being developed include advanced chemical propulsion and aerocapture.

Sustainable Propulsion technologies, such as solar cells and electric propulsion systems powered by renewable energy, are gaining attention for their potential to provide solutions for space travel, whilst aiming for more efficient energy sources and lesser harmful emissions. However, those technologies may be limited in terms of thrust and scalability.

In 2023, Boeing and Airbus are the leading research companies in Sustainable Propulsion for space applications in terms of patent family publications, but mostly focus on hydrogen/fuel cells and sustainable fuels. The most important area in terms of patent family publications is electric propulsion. The number of patent family publications in electric propulsion systems has increased from only 70 in 2000 to 293 in 2023, with the top inventors being from China.

Defining technologies

The term "mission pull" defines a technology or a performance characteristic necessary to meet a planned NASA mission requirement. Any other relationship between a technology and a mission (an alternate propulsion system, for example) is categorized as "technology push." Also, a space demonstration refers to the spaceflight of a scaled version of a particular technology or of a critical technology subsystem. On the other hand, a space validation would serve as a qualification flight for future mission implementation. A successful validation flight would not require any additional space testing of a particular technology before it can be adopted for a science or exploration mission.

Testing

Spacecraft propulsion systems are often first statically tested on Earth's surface, within the atmosphere but many systems require a vacuum chamber to test fully. Rockets are usually tested at a rocket engine test facility well away from habitation and other buildings for safety reasons. Ion drives are far less dangerous and require much less stringent safety, usually only a moderately large vacuum chamber is needed. Static firing of engines are done at ground test facilities, and systems which cannot be adequately tested on the ground and require launches may be employed at a launch site.

In fiction

In science fiction, space ships use various means to travel, some of them scientifically plausible (like solar sails or ramjets), others, mostly or entirely fictitious (like anti-gravity, warp drive, spindizzy or hyperspace travel).