An enzyme is a biological macromolecule, usually a protein, that acts as a biological catalyst, accelerating chemical reactions without being consumed in the process. The molecules on which enzymes act are called substrates, which are converted into products. Nearly all metabolic processes within a cell depend on enzyme catalysis to occur at biologically relevant rates. Metabolic pathways are typically composed of a series of enzyme-catalyzed steps. The study of enzymes is known as enzymology, and a related field focuses on pseudoenzymes—proteins that have lost catalytic activity but may retain regulatory or scaffolding functions, often indicated by alterations in their amino acid sequences or unusual 'pseudocatalytic' behavior.

Enzymes are known to catalyze over 5,000 types of biochemical reactions. Other biological catalysts include catalytic RNA molecules, or ribozymes, which are sometimes classified as enzymes despite being composed of RNA rather than protein. More recently, biomolecular condensates have been recognized as a third category of biocatalysts, capable of catalyzing reactions by creating interfaces and gradients—such as ionic gradients—that drive biochemical processes, even when their component proteins are not intrinsically catalytic.

Enzymes increase the reaction rate by lowering a reaction's activation energy, often by factors of millions. A striking example is orotidine 5'-phosphate decarboxylase, which accelerates a reaction that would otherwise take millions of years to occur in milliseconds. Like all catalysts, enzymes do not affect the overall equilibrium of a reaction and are regenerated at the end of each cycle. What distinguishes them is their high specificity, determined by their unique three-dimensional structure, and their sensitivity to factors such as temperature and pH. Enzyme activity can be enhanced by activators or diminished by inhibitors, many of which serve as drugs or poisons. Outside optimal conditions, enzymes may lose their structure through denaturation, leading to loss of function.

Enzymes have widespread practical applications. In industry, they are used to catalyze the production of antibiotics and other complex molecules. In everyday life, enzymes in biological washing powders break down protein, starch, and fat stains, enhancing cleaning performance. Papain and other proteolytic enzymes are used in meat tenderizers to hydrolyze proteins, improving texture and digestibility. Their specificity and efficiency make enzymes indispensable in both biological systems and commercial processes.

Etymology and history

By the late 17th and early 18th centuries, the digestion of meat by stomach secretions and the conversion of starch to sugars by plant extracts and saliva were known but the mechanisms by which these occurred had not been identified.

French chemist Anselme Payen was the first to discover an enzyme, diastase, in 1833. A few decades later, when studying the fermentation of sugar to alcohol by yeast, Louis Pasteur concluded that this fermentation was caused by a vital force contained within the yeast cells called "ferments", which were thought to function only within living organisms. He wrote that "alcoholic fermentation is an act correlated with the life and organization of the yeast cells, not with the death or putrefaction of the cells."

In 1877, German physiologist Wilhelm Kühne (1837–1900) first used the term enzyme, which comes from Ancient Greek ἔνζυμον (énzymon) 'leavened, in yeast', to describe this process. The word enzyme was used later to refer to nonliving substances such as pepsin, and the word ferment was used to refer to chemical activity produced by living organisms.

Eduard Buchner submitted his first paper on the study of yeast extracts in 1897. In a series of experiments at the University of Berlin, he found that sugar was fermented by yeast extracts even when there were no living yeast cells in the mixture. He named the enzyme that brought about the fermentation of sucrose "zymase". In 1907, he received the Nobel Prize in Chemistry for "his discovery of cell-free fermentation". Following Buchner's example, enzymes are usually named according to the reaction they carry out: the suffix -ase is combined with the name of the substrate (e.g., lactase is the enzyme that cleaves lactose) or to the type of reaction (e.g., DNA polymerase forms DNA polymers).

The biochemical identity of enzymes was still unknown in the early 1900s. Many scientists observed that enzymatic activity was associated with proteins, but others (such as Nobel laureate Richard Willstätter) argued that proteins were merely carriers for the true enzymes and that proteins per se were incapable of catalysis. In 1926, James B. Sumner showed that the enzyme urease was a pure protein and crystallized it; he did likewise for the enzyme catalase in 1937. The conclusion that pure proteins can be enzymes was definitively demonstrated by John Howard Northrop and Wendell Meredith Stanley, who worked on the digestive enzymes pepsin (1930), trypsin and chymotrypsin. These three scientists were awarded the 1946 Nobel Prize in Chemistry.

The discovery that enzymes could be crystallized eventually allowed their structures to be solved by x-ray crystallography. This was first done for lysozyme, an enzyme found in tears, saliva and egg whites that digests the coating of some bacteria; the structure was solved by a group led by David Chilton Phillips and published in 1965. This high-resolution structure of lysozyme marked the beginning of the field of structural biology and the effort to understand how enzymes work at an atomic level of detail.

Classification and nomenclature

Enzymes can be classified by two main criteria: either amino acid sequence similarity (and thus evolutionary relationship) or enzymatic activity.

Enzyme activity. An enzyme's name is often derived from its substrate or the chemical reaction it catalyzes, with the word ending in -ase. Examples are lactase, alcohol dehydrogenase and DNA polymerase. Different enzymes that catalyze the same chemical reaction are called isozymes.

The International Union of Biochemistry and Molecular Biology have developed a nomenclature for enzymes, the EC numbers (for "Enzyme Commission"). Each enzyme is described by "EC" followed by a sequence of four numbers which represent the hierarchy of enzymatic activity (from very general to very specific). That is, the first number broadly classifies the enzyme based on its mechanism while the other digits add more and more specificity.

The top-level classification is:

- EC 1, Oxidoreductases: catalyze oxidation/reduction reactions

- EC 2, Transferases: transfer a functional group (e.g. a methyl or phosphate group)

- EC 3, Hydrolases: catalyze the hydrolysis of various bonds

- EC 4, Lyases: cleave various bonds by means other than hydrolysis and oxidation

- EC 5, Isomerases: catalyze isomerization changes within a single molecule

- EC 6, Ligases: join two molecules with covalent bonds.

- EC 7, Translocases: catalyze the movement of ions or molecules across membranes, or their separation within membranes.

These sections are subdivided by other features such as the substrate, products, and chemical mechanism. An enzyme is fully specified by four numerical designations. For example, hexokinase (EC 2.7.1.1) is a transferase (EC 2) that adds a phosphate group (EC 2.7) to a hexose sugar, a molecule containing an alcohol group (EC 2.7.1).[22]

Sequence similarity. EC categories do not reflect sequence similarity. For instance, two ligases of the same EC number that catalyze exactly the same reaction can have completely different sequences. Independent of their function, enzymes, like any other proteins, have been classified by their sequence similarity into numerous families. These families have been documented in dozens of different protein and protein family databases such as Pfam.

Non-homologous isofunctional enzymes. Unrelated enzymes that have the same enzymatic activity have been called non-homologous isofunctional enzymes. Horizontal gene transfer may spread these genes to unrelated species, especially bacteria where they can replace endogenous genes of the same function, leading to hon-homologous gene displacement.

Structure

Enzymes are generally globular proteins, acting alone or in larger complexes. The sequence of the amino acids specifies the structure which in turn determines the catalytic activity of the enzyme. Although structure determines function, a novel enzymatic activity cannot yet be predicted from structure alone. Enzyme structures unfold (denature) when heated or exposed to chemical denaturants and this disruption to the structure typically causes a loss of activity. Enzyme denaturation is normally linked to temperatures above a species' normal level; as a result, enzymes from bacteria living in volcanic environments such as hot springs are prized by industrial users for their ability to function at high temperatures, allowing enzyme-catalysed reactions to be operated at a very high rate.

Enzymes are usually much larger than their substrates. Sizes range from just 62 amino acid residues, for the monomer of 4-oxalocrotonate tautomerase, to over 2,500 residues in the animal fatty acid synthase. Only a small portion of their structure (around 2–4 amino acids) is directly involved in catalysis: the catalytic site. This catalytic site is located next to one or more binding sites where residues orient the substrates. The catalytic site and binding site together compose the enzyme's active site. The remaining majority of the enzyme structure serves to maintain the precise orientation and dynamics of the active site.

In some enzymes, no amino acids are directly involved in catalysis; instead, the enzyme contains sites to bind and orient catalytic cofactors.[31] Enzyme structures may also contain allosteric sites where the binding of a small molecule causes a conformational change that increases or decreases activity.

A small number of RNA-based biological catalysts called ribozymes exist, which again can act alone or in complex with proteins. The most common of these is the ribosome which is a complex of protein and catalytic RNA components.

Mechanism

Substrate binding

Enzymes must bind their substrates before they can catalyse any chemical reaction. Enzymes are usually very specific as to what substrates they bind and then the chemical reaction catalysed. Specificity is achieved by binding pockets with complementary shape, charge and hydrophilic/hydrophobic characteristics to the substrates. Enzymes can therefore distinguish between very similar substrate molecules to be chemoselective, regioselective and stereospecific.

Some of the enzymes showing the highest specificity and accuracy are involved in the copying and expression of the genome. Some of these enzymes have "proof-reading" mechanisms. Here, an enzyme such as DNA polymerase catalyzes a reaction in a first step and then checks that the product is correct in a second step. This two-step process results in average error rates of less than 1 error in 100 million reactions in high-fidelity mammalian polymerases. Similar proofreading mechanisms are also found in RNA polymerase, aminoacyl tRNA synthetases and ribosomes.

Conversely, some enzymes display enzyme promiscuity, having broad specificity and acting on a range of different physiologically relevant substrates. Many enzymes possess small side activities which arose fortuitously (i.e. neutrally), which may be the starting point for the evolutionary selection of a new function.

"Lock and key" model

To explain the observed specificity of enzymes, in 1894 Emil Fischer proposed that both the enzyme and the substrate possess specific complementary geometric shapes that fit exactly into one another. This is often referred to as "the lock and key" model. This early model explains enzyme specificity, but fails to explain the stabilization of the transition state that enzymes achieve.

Induced fit model

In 1958, Daniel Koshland suggested a modification to the lock and key model: since enzymes are rather flexible structures, the active site is continuously reshaped by interactions with the substrate as the substrate interacts with the enzyme. As a result, the substrate does not simply bind to a rigid active site; the amino acid side-chains that make up the active site are molded into the precise positions that enable the enzyme to perform its catalytic function. In some cases, such as glycosidases, the substrate molecule also changes shape slightly as it enters the active site. The active site continues to change until the substrate is completely bound, at which point the final shape and charge distribution is determined. Induced fit may enhance the fidelity of molecular recognition in the presence of competition and noise via the conformational proofreading mechanism.

Catalysis

Enzymes can accelerate reactions in several ways, all of which lower the activation energy (ΔG‡, Gibbs free energy)

- By stabilizing the transition state:

- Creating an environment with a charge distribution complementary to that of the transition state to lower its energy

- By providing an alternative reaction pathway:

- Temporarily reacting with the substrate, forming a covalent intermediate to provide a lower energy transition state

- By destabilizing the substrate ground state:

- Distorting bound substrate(s) into their transition state form to reduce the energy required to reach the transition state

- By orienting the substrates into a productive arrangement to reduce the reaction entropy change (the contribution of this mechanism to catalysis is relatively small)

Enzymes may use several of these mechanisms simultaneously. For example, proteases such as trypsin perform covalent catalysis using a catalytic triad, stabilize charge build-up on the transition states using an oxyanion hole, complete hydrolysis using an oriented water substrate.

Dynamics

Enzymes are not rigid, static structures; instead they have complex internal dynamic motions – that is, movements of parts of the enzyme's structure such as individual amino acid residues, groups of residues forming a protein loop or unit of secondary structure, or even an entire protein domain. These motions give rise to a conformational ensemble of slightly different structures that interconvert with one another at equilibrium. Different states within this ensemble may be associated with different aspects of an enzyme's function. For example, different conformations of the enzyme dihydrofolate reductase are associated with the substrate binding, catalysis, cofactor release, and product release steps of the catalytic cycle, consistent with catalytic resonance theory. The transitions between the different conformations during the catalytic cycle involve internal viscoelastic motion that is facilitated by high-strain regions where amino acids are rearranged.

Substrate presentation

Substrate presentation is a process where the enzyme is sequestered away from its substrate. Enzymes can be sequestered to the plasma membrane away from a substrate in the nucleus or cytosol.[55] Or within the membrane, an enzyme can be sequestered into lipid rafts away from its substrate in the disordered region. When the enzyme is released it mixes with its substrate. Alternatively, the enzyme can be sequestered near its substrate to activate the enzyme. For example, the enzyme can be soluble and upon activation bind to a lipid in the plasma membrane and then act upon molecules in the plasma membrane.

Allosteric modulation

Allosteric sites are pockets on the enzyme, distinct from the active site, that bind to molecules in the cellular environment. These molecules then cause a change in the conformation or dynamics of the enzyme that is transduced to the active site and thus affects the reaction rate of the enzyme. In this way, allosteric interactions can either inhibit or activate enzymes. Allosteric interactions with metabolites upstream or downstream in an enzyme's metabolic pathway cause feedback regulation, altering the activity of the enzyme according to the flux through the rest of the pathway.

Cofactors

Some enzymes do not need additional components to show full activity. Others require non-protein molecules called cofactors to be bound for activity. Cofactors can be either inorganic (e.g., metal ions and iron–sulfur clusters) or organic compounds (e.g., flavin and heme). These cofactors serve many purposes; for instance, metal ions can help in stabilizing nucleophilic species within the active site. Organic cofactors can be either coenzymes, which are released from the enzyme's active site during the reaction, or prosthetic groups, which are tightly bound to an enzyme. Organic prosthetic groups can be covalently bound (e.g., biotin in enzymes such as pyruvate carboxylase).

An example of an enzyme that contains a cofactor is carbonic anhydrase, which uses a zinc cofactor bound as part of its active site. These tightly bound ions or molecules are usually found in the active site and are involved in catalysis. For example, flavin and heme cofactors are often involved in redox reactions.

Enzymes that require a cofactor but do not have one bound are called apoenzymes or apoproteins. An enzyme together with the cofactor(s) required for activity is called a holoenzyme (or haloenzyme). The term holoenzyme can also be applied to enzymes that contain multiple protein subunits, such as the DNA polymerases; here the holoenzyme is the complete complex containing all the subunits needed for activity.

Coenzymes

Coenzymes are small organic molecules that can be loosely or tightly bound to an enzyme. Coenzymes transport chemical groups from one enzyme to another. Examples include NADH, NADPH and adenosine triphosphate (ATP). Some coenzymes, such as flavin mononucleotide (FMN), flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD), thiamine pyrophosphate (TPP), and tetrahydrofolate (THF), are derived from vitamins. These coenzymes cannot be synthesized by the body de novo and closely related compounds (vitamins) must be acquired from the diet. The chemical groups carried include:

- the hydride ion (H−), carried by NAD or NADP+

- the phosphate group, carried by adenosine triphosphate

- the acetyl group, carried by coenzyme A

- formyl, methenyl or methyl groups, carried by folic acid and

- the methyl group, carried by S-adenosylmethionine

Since coenzymes are chemically changed as a consequence of enzyme action, it is useful to consider coenzymes to be a special class of substrates, or second substrates, which are common to many different enzymes. For example, about 1000 enzymes are known to use the coenzyme NADH.

Coenzymes are usually continuously regenerated and their concentrations maintained at a steady level inside the cell. For example, NADPH is regenerated through the pentose phosphate pathway and S-adenosylmethionine by methionine adenosyltransferase. This continuous regeneration means that small amounts of coenzymes can be used very intensively. For example, the human body turns over its own weight in ATP each day.

Thermodynamics

As with all catalysts, enzymes do not alter the position of the chemical equilibrium of the reaction. In the presence of an enzyme, the reaction runs in the same direction as it would without the enzyme, just more quickly. For example, carbonic anhydrase catalyzes its reaction in either direction depending on the concentration of its reactants:

| (in tissues; high CO2 concentration) | 1 |

| (in lungs; low CO2 concentration) | 2 |

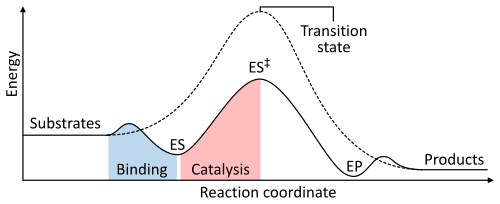

The rate of a reaction is dependent on the activation energy needed to form the transition state which then decays into products. Enzymes increase reaction rates by lowering the energy of the transition state. First, binding forms a low energy enzyme-substrate complex (ES). Second, the enzyme stabilises the transition state such that it requires less energy to achieve compared to the uncatalyzed reaction (ES‡). Finally the enzyme-product complex (EP) dissociates to release the products.

Enzymes can couple two or more reactions, so that a thermodynamically favorable reaction can be used to "drive" a thermodynamically unfavourable one so that the combined energy of the products is lower than the substrates. For example, the hydrolysis of ATP is often used to drive other chemical reactions.

Kinetics

Enzyme kinetics is the investigation of how enzymes bind substrates and turn them into products. The rate data used in kinetic analyses are commonly obtained from enzyme assays. In 1913 Leonor Michaelis and Maud Leonora Menten proposed a quantitative theory of enzyme kinetics, which is referred to as Michaelis–Menten kinetics. The major contribution of Michaelis and Menten was to think of enzyme reactions in two stages. In the first, the substrate binds reversibly to the enzyme, forming the enzyme-substrate complex. This is sometimes called the Michaelis–Menten complex in their honor. The enzyme then catalyzes the chemical step in the reaction and releases the product. This work was further developed by G. E. Briggs and J. B. S. Haldane, who derived kinetic equations that are still widely used today.

Enzyme rates depend on solution conditions and substrate concentration. To find the maximum speed of an enzymatic reaction, the substrate concentration is increased until a constant rate of product formation is seen. This is shown in the saturation curve on the right. Saturation happens because, as substrate concentration increases, more and more of the free enzyme is converted into the substrate-bound ES complex. At the maximum reaction rate (Vmax) of the enzyme, all the enzyme active sites are bound to substrate, and the amount of ES complex is the same as the total amount of enzyme.

Vmax is only one of several important kinetic parameters. The amount of substrate needed to achieve a given rate of reaction is also important. This is given by the Michaelis–Menten constant (Km), which is the substrate concentration required for an enzyme to reach one-half its maximum reaction rate; generally, each enzyme has a characteristic KM for a given substrate. Another useful constant is kcat, also called the turnover number, which is the number of substrate molecules handled by one active site per second.

The efficiency of an enzyme can be expressed in terms of kcat/Km. This is also called the specificity constant and incorporates the rate constants for all steps in the reaction up to and including the first irreversible step. Because the specificity constant reflects both affinity and catalytic ability, it is useful for comparing different enzymes against each other, or the same enzyme with different substrates. The theoretical maximum for the specificity constant is called the diffusion limit and is about 108 to 109 (M−1 s−1). At this point every collision of the enzyme with its substrate will result in catalysis, and the rate of product formation is not limited by the reaction rate but by the diffusion rate. Enzymes with this property are called catalytically perfect or kinetically perfect. Example of such enzymes are triose-phosphate isomerase, carbonic anhydrase, acetylcholinesterase, catalase, fumarase, β-lactamase, and superoxide dismutase. The turnover of such enzymes can reach several million reactions per second. But most enzymes are far from perfect: the average values of and are about and , respectively.

Michaelis–Menten kinetics relies on the law of mass action, which is derived from the assumptions of free diffusion and thermodynamically driven random collision. Many biochemical or cellular processes deviate significantly from these conditions, because of macromolecular crowding and constrained molecular movement. More recent, complex extensions of the model attempt to correct for these effects.

Inhibition

Enzyme reaction rates can be decreased by various types of enzyme inhibitors.

Types of inhibition

Competitive

A competitive inhibitor and substrate cannot bind to the enzyme at the same time. Often competitive inhibitors strongly resemble the real substrate of the enzyme. For example, the drug methotrexate is a competitive inhibitor of the enzyme dihydrofolate reductase, which catalyzes the reduction of dihydrofolate to tetrahydrofolate. The similarity between the structures of dihydrofolate and this drug are shown in the accompanying figure. This type of inhibition can be overcome with high substrate concentration. In some cases, the inhibitor can bind to a site other than the binding-site of the usual substrate and exert an allosteric effect to change the shape of the usual binding-site.

Non-competitive

A non-competitive inhibitor binds to a site other than where the substrate binds. The substrate still binds with its usual affinity and hence Km remains the same. However the inhibitor reduces the catalytic efficiency of the enzyme so that Vmax is reduced. In contrast to competitive inhibition, non-competitive inhibition cannot be overcome with high substrate concentration.

Uncompetitive

An uncompetitive inhibitor cannot bind to the free enzyme, only to the enzyme-substrate complex; hence, these types of inhibitors are most effective at high substrate concentration. In the presence of the inhibitor, the enzyme-substrate complex is inactive. This type of inhibition is rare.

Mixed

A mixed inhibitor binds to an allosteric site and the binding of the substrate and the inhibitor affect each other. The enzyme's function is reduced but not eliminated when bound to the inhibitor. This type of inhibitor does not follow the Michaelis–Menten equation.

Irreversible

An irreversible inhibitor permanently inactivates the enzyme, usually by forming a covalent bond to the protein. Penicillin and aspirin are common drugs that act in this manner.

Functions of inhibitors

In many organisms, inhibitors may act as part of a feedback mechanism. If an enzyme produces too much of one substance in the organism, that substance may act as an inhibitor for the enzyme at the beginning of the pathway that produces it, causing production of the substance to slow down or stop when there is sufficient amount. This is a form of negative feedback. Major metabolic pathways such as the citric acid cycle make use of this mechanism.

Since inhibitors modulate the function of enzymes they are often used as drugs. Many such drugs are reversible competitive inhibitors that resemble the enzyme's native substrate, similar to methotrexate above; other well-known examples include statins used to treat high cholesterol, and protease inhibitors used to treat retroviral infections such as HIV. A common example of an irreversible inhibitor that is used as a drug is aspirin, which inhibits the COX-1 and COX-2 enzymes that produce the inflammation messenger prostaglandin. Other enzyme inhibitors are poisons. For example, the poison cyanide is an irreversible enzyme inhibitor that combines with the copper and iron in the active site of the enzyme cytochrome c oxidase and blocks cellular respiration.

Factors affecting enzyme activity

As enzymes are made up of proteins, their actions are sensitive to change in many physio chemical factors such as pH, temperature, substrate concentration, etc.

The following table shows pH optima for various enzymes.

| Enzyme | Optimum pH | pH description |

|---|---|---|

| Pepsin | 1.5–1.6 | Highly acidic |

| Invertase | 4.5 | Acidic |

| Lipase (stomach) | 4.0–5.0 | Acidic |

| Lipase (castor oil) | 4.7 | Acidic |

| Lipase (pancreas) | 8.0 | Alkaline |

| Amylase (malt) | 4.6–5.2 | Acidic |

| Amylase (pancreas) | 6.7–7.0 | Acidic-neutral |

| Cellobiase | 5.0 | Acidic |

| Maltase | 6.1–6.8 | Acidic |

| Sucrase | 6.2 | Acidic |

| Catalase | 7.0 | Neutral |

| Urease | 7.0 | Neutral |

| Cholinesterase | 7.0 | Neutral |

| Ribonuclease | 7.0–7.5 | Neutral |

| Fumarase | 7.8 | Alkaline |

| Trypsin | 7.8–8.7 | Alkaline |

| Adenosine triphosphate | 9.0 | Alkaline |

| Arginase | 10.0 | Highly alkaline |

Biological function

Enzymes serve a wide variety of functions inside living organisms. They are indispensable for signal transduction and cell regulation, often via kinases and phosphatases. They also generate movement, with myosin hydrolyzing adenosine triphosphate (ATP) to generate muscle contraction, and also transport cargo around the cell as part of the cytoskeleton. Other ATPases in the cell membrane are ion pumps involved in active transport. Enzymes are also involved in more exotic functions, such as luciferase generating light in fireflies. Viruses can also contain enzymes for infecting cells, such as the HIV integrase and reverse transcriptase, or for viral release from cells, like the influenza virus neuraminidase.

An important function of enzymes is in the digestive systems of animals. Enzymes such as amylases and proteases break down large molecules (starch or proteins, respectively) into smaller ones, so they can be absorbed by the intestines. Starch molecules, for example, are too large to be absorbed from the intestine, but enzymes hydrolyze the starch chains into smaller molecules such as maltose and eventually glucose, which can then be absorbed. Different enzymes digest different food substances. In ruminants, which have herbivorous diets, microorganisms in the gut produce another enzyme, cellulase, to break down the cellulose cell walls of plant fiber.

Metabolism

Several enzymes can work together in a specific order, creating metabolic pathways. In a metabolic pathway, one enzyme takes the product of another enzyme as a substrate. After the catalytic reaction, the product is then passed on to another enzyme. Sometimes more than one enzyme can catalyze the same reaction in parallel; this can allow more complex regulation: with, for example, a low constant activity provided by one enzyme but an inducible high activity from a second enzyme.

Enzymes determine what steps occur in these pathways. Without enzymes, metabolism would neither progress through the same steps and could not be regulated to serve the needs of the cell. Most central metabolic pathways are regulated at a few steps, typically through enzymes whose activity involves the phosphorylation by ATP. Because this reaction releases so much energy, other reactions that are thermodynamically unfavorable can be coupled to ATP hydrolysis, driving the overall series of linked metabolic reactions.

Control of activity

There are five main ways that enzyme activity is controlled in the cell.

Regulation

Enzymes can be either activated or inhibited by other molecules. For example, the end product(s) of a metabolic pathway are often inhibitors for one of the first enzymes of the pathway (usually the first irreversible step, called committed step), thus regulating the amount of end product made by the pathways. Such a regulatory mechanism is called a negative feedback mechanism, because the amount of the end product produced is regulated by its own concentration. Negative feedback mechanism can effectively adjust the rate of synthesis of intermediate metabolites according to the demands of the cells. This helps with effective allocations of materials and energy economy, and it prevents the excess manufacture of end products. Like other homeostatic devices, the control of enzymatic action helps to maintain a stable internal environment in living organisms.

Post-translational modification

Examples of post-translational modification include phosphorylation, myristoylation and glycosylation. For example, in the response to insulin, the phosphorylation of multiple enzymes, including glycogen synthase, helps control the synthesis or degradation of glycogen and allows the cell to respond to changes in blood sugar. Another example of post-translational modification is the cleavage of the polypeptide chain. Chymotrypsin, a digestive protease, is produced in inactive form as chymotrypsinogen in the pancreas and transported in this form to the stomach where it is activated. This stops the enzyme from digesting the pancreas or other tissues before it enters the gut. This type of inactive precursor to an enzyme is known as a zymogen or proenzyme.

Quantity

Enzyme production (transcription and translation of enzyme genes) can be enhanced or diminished by a cell in response to changes in the cell's environment. This form of gene regulation is called enzyme induction. For example, bacteria may become resistant to antibiotics such as penicillin because enzymes called beta-lactamases are induced that hydrolyse the crucial beta-lactam ring within the penicillin molecule. Another example comes from enzymes in the liver called cytochrome P450 oxidases, which are important in drug metabolism. Induction or inhibition of these enzymes can cause drug interactions. Enzyme levels can also be regulated by changing the rate of enzyme degradation. The opposite of enzyme induction is enzyme repression.

Subcellular distribution

Enzymes can be compartmentalized, with different metabolic pathways occurring in different cellular compartments. For example, fatty acids are synthesized by one set of enzymes in the cytosol, endoplasmic reticulum and Golgi and used by a different set of enzymes as a source of energy in the mitochondrion, through β-oxidation. In addition, trafficking of the enzyme to different compartments may change the degree of protonation (e.g., the neutral cytoplasm and the acidic lysosome) or oxidative state (e.g., oxidizing periplasm or reducing cytoplasm) which in turn affects enzyme activity. In contrast to partitioning into membrane bound organelles, enzyme subcellular localisation may also be altered through polymerisation of enzymes into macromolecular cytoplasmic filaments.

Organ specialization

In multicellular eukaryotes, cells in different organs and tissues have different patterns of gene expression and therefore have different sets of enzymes (known as isozymes) available for metabolic reactions. This provides a mechanism for regulating the overall metabolism of the organism. For example, hexokinase, the first enzyme in the glycolysis pathway, has a specialized form called glucokinase expressed in the liver and pancreas that has a lower affinity for glucose yet is more sensitive to glucose concentration. This enzyme is involved in sensing blood sugar and regulating insulin production.

Involvement in disease

Since the tight control of enzyme activity is essential for homeostasis, any malfunction (mutation, overproduction, underproduction or deletion) of a single critical enzyme can lead to a genetic disease. The malfunction of just one type of enzyme out of the thousands of types present in the human body can be fatal. An example of a fatal genetic disease due to enzyme insufficiency is Tay–Sachs disease, in which patients lack the enzyme hexosaminidase.

One example of enzyme deficiency is the most common type of phenylketonuria. Many different single amino acid mutations in the enzyme phenylalanine hydroxylase, which catalyzes the first step in the degradation of phenylalanine, result in build-up of phenylalanine and related products. Some mutations are in the active site, directly disrupting binding and catalysis, but many are far from the active site and reduce activity by destabilising the protein structure, or affecting correct oligomerisation. This can lead to intellectual disability if the disease is untreated. Another example is pseudocholinesterase deficiency, in which the body's ability to break down choline ester drugs is impaired. Oral administration of enzymes can be used to treat some functional enzyme deficiencies, such as pancreatic insufficiency and lactose intolerance.

Another way enzyme malfunctions can cause disease comes from germline mutations in genes coding for DNA repair enzymes. Defects in these enzymes cause cancer because cells are less able to repair mutations in their genomes. This causes a slow accumulation of mutations and results in the development of cancers. An example of such a hereditary cancer syndrome is xeroderma pigmentosum, which causes the development of skin cancers in response to even minimal exposure to ultraviolet light.

Evolution

Similar to any other protein, enzymes change over time through mutations and sequence divergence. Given their central role in metabolism, enzyme evolution plays a critical role in adaptation. A key question is therefore whether and how enzymes can change their enzymatic activities alongside. It is generally accepted that many new enzyme activities have evolved through gene duplication and mutation of the duplicate copies although evolution can also happen without duplication. One example of an enzyme that has changed its activity is the ancestor of methionyl aminopeptidase (MAP) and creatine amidinohydrolase (creatinase) which are clearly homologous but catalyze very different reactions (MAP removes the amino-terminal methionine in new proteins while creatinase hydrolyses creatine to sarcosine and urea). In addition, MAP is metal-ion dependent while creatinase is not, hence this property was also lost over time. Small changes of enzymatic activity are extremely common among enzymes. In particular, substrate binding specificity (see above) can easily and quickly change with single amino acid changes in their substrate binding pockets. This is frequently seen in the main enzyme classes such as kinases.

Artificial (in vitro) evolution is now commonly used to modify enzyme activity or specificity for industrial applications (see below).

Industrial applications

Enzymes are used in the chemical industry and other industrial applications when extremely specific catalysts are required. Enzymes in general are limited in the number of reactions they have evolved to catalyze and also by their lack of stability in organic solvents and at high temperatures. As a consequence, protein engineering is an active area of research and involves attempts to create new enzymes with novel properties, either through rational design or in vitro evolution. These efforts have begun to be successful, and a few enzymes have now been designed "from scratch" to catalyze reactions that do not occur in nature.

| Application | Enzymes used | Uses |

|---|---|---|

| Biofuel industry | Cellulases | Break down cellulose into sugars that can be fermented to produce cellulosic ethanol. |

| Ligninases | Pretreatment of biomass for biofuel production. | |

| Biological detergent | Proteases, amylases, lipases | Remove protein, starch, and fat or oil stains from laundry and dishware. |

| Mannanases | Remove food stains from the common food additive guar gum. | |

| Brewing industry | Amylase, glucanases, proteases | Split polysaccharides and proteins in the malt. |

| Betaglucanases | Improve the wort and beer filtration characteristics. | |

| Amyloglucosidase and pullulanases | Make low-calorie beer and adjust fermentability. | |

| Acetolactate decarboxylase (ALDC) | Increase fermentation efficiency by reducing diacetyl formation. | |

| Culinary uses | Papain | Tenderize meat for cooking. |

| Dairy industry | Rennin | Hydrolyze protein in the manufacture of cheese. |

| Lipases | Produce Camembert cheese and blue cheeses such as Roquefort. | |

| Food processing | Amylases | Produce sugars from starch, such as in making high-fructose corn syrup. |

| Proteases | Lower the protein level of flour, as in biscuit-making. | |

| Trypsin | Manufacture hypoallergenic baby foods. | |

| Cellulases, pectinases | Clarify fruit juices. | |

| Molecular biology | Nucleases, DNA ligase and polymerases | Use restriction digestion and the polymerase chain reaction to create recombinant DNA. |

| Paper industry | Xylanases, hemicellulases and lignin peroxidases | Remove lignin from kraft pulp. |

| Personal care | Proteases | Remove proteins on contact lenses to prevent infections. |

| Starch industry | Amylases | Convert starch into glucose and various syrups. |

![{\displaystyle {\mathrm {CO} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}{}+{}\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}\mathrm {O} {}\mathrel {\xrightarrow {\text{Carbonic anhydrase}} } {}\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}\mathrm {CO} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{3}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/cb4c8837b26e96fe552c17d863f93e0618cd998b)

![{\displaystyle {\mathrm {CO} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}{}+{}\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}\mathrm {O} {}\mathrel {\xleftarrow {\text{Carbonic anhydrase}} } {}\mathrm {H} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{2}}\mathrm {CO} {\vphantom {A}}_{\smash[{t}]{3}}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/618e95485aa1c3c44a29c557ac448ae5b544ff07)