Sustainable development is an approach to growth and human development that aims to meet the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. The aim is to have a society where living conditions and resources meet human needs without undermining planetary integrity. Sustainable development aims to balance the needs of the economy, environment, and society. The Brundtland Report in 1987 helped to make the concept of sustainable development better known.

Sustainable development overlaps with the idea of sustainability which is a normative concept. UNESCO formulated a distinction between the two concepts as follows: "Sustainability is often thought of as a long-term goal (i.e. a more sustainable world), while sustainable development refers to the many processes and pathways to achieve it."

The Rio Process that began at the 1992 Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro has placed the concept of sustainable development on the international agenda. Sustainable development is the foundational concept of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). These global goals for the year 2030 were adopted in 2015 by the United Nations General Assembly (UNGA). They address the global challenges, including poverty, climate change, biodiversity loss, and peace.

There are some problems with the concept of sustainable development. Some scholars say it is an oxymoron because according to them, development is inherently unsustainable. Other commentators are disappointed in the lack of progress that has been achieved so far. Scholars have stated that "sustainable development" is open-ended, ambiguous, and incoherent, so it can be easily appropriated. Furthermore, while digitalization is often promoted as a tool for sustainable development, recent scholarly analysis has introduced a more complex view, indicating that the rapid reliance on digital technologies can have a negative overall impact on environmental sustainability, despite positive influences on economic and social development aspects.

Therefore, it is important that there is increased funding for research on sustainability in order to better understand sustainable development and address its vagueness and shortcomings.

Definition

In 1987, the United Nations World Commission on Environment and Development released the report Our Common Future, commonly called the Brundtland Report. The report included a definition of "sustainable development" which is now widely used:

Sustainable development is a development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs. It contains two key concepts within it:

- The concept of 'needs', in particular, the essential needs of the world's poor, to which overriding priority should be given; and

- The idea of limitations imposed by the state of technology and social organization on the environment's ability to meet present and future needs.

Sustainable development thus tries to find a balance between economic development, environmental protection, and social well-being.

Scholars note that sustainable development is understood in many different ways. They also highlight inconsistencies in the current market-driven system of social, economic and political organization. Efforts toward global sustainability must consider the diverse challenges, conditions, and choices that affect prospects and prosperity for all, everywhere.

Sustainability means different things to different people, and the concept of sustainable development has led to a diversity of discourses that legitimize competing sociopolitical projects.

Development of the concept

Sustainable development has its roots in ideas regarding sustainable forest management, which were developed in Europe during the 17th and 18th centuries. In response to a growing awareness of the depletion of timber resources in England, John Evelyn argued, in his 1662 essay Sylva, that "sowing and planting of trees had to be regarded as a national duty of every landowner, in order to stop the destructive over- exploitation of natural resources." In 1713, Hans Carl von Carlowitz, a senior mining administrator in the service of Elector Frederick Augustus I of Saxony published Sylvicultura economics, a 400-page work on forestry. Building upon the ideas of Evelyn and French minister Jean-Baptiste Colbert, von Carlowitz developed the concept of managing forests for sustained yield. His work influenced others, including Alexander von Humboldt and Georg Ludwig Hartig, eventually leading to the development of the science of forestry. This, in turn, influenced people like Gifford Pinchot, the first head of the US Forest Service, whose approach to forest management was driven by the idea of wise use of resources, and Aldo Leopold whose land ethic was influential in the development of the environmental movement in the 1960s.

Following the publication of Rachel Carson's Silent Spring in 1962, the developing environmental movement drew attention to the relationship between economic growth and environmental degradation. Kenneth E. Boulding, in his influential 1966 essay The Economics of the Coming Spaceship Earth, identified the need for the economic system to fit itself to the ecological system with its limited pools of resources. Another milestone was the 1968 article by Garrett Hardin that popularized the term "tragedy of the commons".

The direct linking of sustainability and development in a contemporary sense can be traced to the early 1970s. "Strategy of Progress", a 1972 book (in German) by Ernst Basler, explained how the long-acknowledged sustainability concept of preserving forests for future wood production can be directly transferred to the broader importance of preserving environmental resources to sustain the world for future generations. That same year, the interrelationship of environment and development was formally demonstrated in a systems dynamic simulation model reported in the classic report on Limits to Growth. This was commissioned by the Club of Rome and written by a group of scientists led by Dennis and Donella Meadows of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. Describing the desirable "state of global equilibrium", the authors wrote: "We are searching for a model output that represents a world system that is sustainable without sudden and uncontrolled collapse and capable of satisfying the basic material requirements of all of its people." The year 1972 also saw the publication of the influential book, A Blueprint for Survival.

In 1975, an MIT research group prepared ten days of hearings on "Growth and Its Implication for the Future" for the US Congress, the first hearings ever held on sustainable development.

In 1980, the International Union for Conservation of Nature published a world conservation strategy that included one of the first references to sustainable development as a global priority and introduced the term "sustainable development". Two years later, the United Nations World Charter for Nature raised five principles of conservation by which human conduct affecting nature is to be guided and judged.

Since the Brundtland Report, the concept of sustainable development has developed beyond the initial intergenerational framework to focus more on the goal of "socially inclusive and environmentally sustainable economic growth". In 1992, the UN Conference on Environment and Development published the Earth Charter, which outlines the building of a just, sustainable, and peaceful global society in the 21st century. The action plan Agenda 21 for sustainable development identified information, integration, and participation as key building blocks to help countries achieve development that recognizes these interdependent pillars. Furthermore, Agenda 21 emphasizes that broad public participation in decision-making is a fundamental prerequisite for achieving sustainable development.

The Rio Protocol was a huge leap forward: for the first time, the world agreed on a sustainability agenda. In fact, a global consensus was facilitated by neglecting concrete goals and operational details.

Whilst the discussions about (or discourse of) sustainable development are highly influential in global and national governance frameworks, its meaning and operationalization are context-dependent and have evolved over time. This evolution can for example be seen in the transition from the Millennium Development Goals (years 2000 to 2015) to the Sustainable Development Goals (years 2015 to 2030).

Global governance framework

The most comprehensive global governance framework for sustainable development is the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development with its 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). This agenda was a follow-up to the Millennium Declaration from the year 2000 with its eight Millennium Development Goals (MDGs), the first comprehensive global governance framework for sustainable development. The SDGs have concrete targets (unlike the results from the Rio Process) but no methods for sanctions. They contain goals, targets and indicators for example in the areas of poverty reduction, environmental protection, human prosperity and peace.

Scholars who are investigating global environmental governance have identified a set of discourses within the public space that mostly convey four sustainability frames: mainstream sustainability, progressive sustainability, a limits discourse, and radical sustainability. First, mainstream sustainability is a conservative approach on both economic and political terms. Second, progressive sustainability is an economically conservative, yet politically reformist approach. Under this framing, sustainable development is still centered on economic growth but human well-being and development can only be achieved through a redistribution of power to even out inequalities between developed and developing countries. Third, a limits discourse is an economically reformist, yet politically conservative approach to sustainability. Fourth, radical sustainability is a transformative approach seeking to break with existing global economic and political structures.

Related concepts

Sustainability

Sustainability (from the latin sustinere - hold up, hold upright; furnish with means of support; bear, undergo, endure) is the ability to continue over a long period of time. In modern usage it generally refers to a state in which the environment, economy, and society will continue to exist over a long period of time. Many definitions emphasize the environmental dimension. This can include addressing key environmental problems, such as climate change and biodiversity loss. The idea of sustainability can guide decisions at the global, national, organizational, and individual levels. A related concept is that of sustainable development, and the terms are often used to mean the same thing. UNESCO distinguishes the two like this: "Sustainability is often thought of as a long-term goal (i.e. a more sustainable world), while sustainable development refers to the many processes and pathways to achieve it."

Dimensions

Sustainable development, like sustainability, is regarded to have three dimensions: the environment, economy and society. The idea is that a good balance between the three dimensions should be achieved. Instead of calling them dimensions, other terms commonly used are pillars, domains, aspects, spheres.

Scholars usually distinguish three different areas of sustainability. These are the environmental, the social, and the economic. Several terms are in use for this concept. Authors may speak of three pillars, dimensions, components, aspects, perspectives, factors, or goals. All mean the same thing in this context. The three dimensions paradigm has few theoretical foundations.

Countries could develop systems for monitoring and evaluation of progress towards achieving sustainable development by adopting indicators that measure changes across economic, social and environmental dimensions.

Pathways

Six interdependent capacities are deemed to be necessary for the successful pursuit of sustainable development. These are the capacities to measure progress towards sustainable development; promote equity within and between generations; adapt to shocks and surprises; transform the system onto more sustainable development pathways; link knowledge with action for sustainability; and to devise governance arrangements that allow people to work together.

During the MDG era (year 2000 to 2015), the key objective of sustainable development was poverty reduction to be reached through economic growth and participation in the global trade system. The SDGs take a much more comprehensive approach to sustainable development than the MDGs did. They offer a more people-centered development agenda. Out of the 17 SDGs, for example, 11 goals contain targets related to equity, equality or inclusion, and SDG 10 is solely devoted to addressing inequality within and among countries.

Improving on environmental sustainability

An unsustainable situation occurs when natural capital (the total of nature's resources) is used up faster than it can be replenished. Sustainability requires that human activity only uses nature's resources at a rate at which they can be replenished naturally. The concept of sustainable development is intertwined with the concept of carrying capacity. Theoretically, the long-term result of environmental degradation is the inability to sustain human life.

Important operational principles of sustainable development were published by Herman Daly in 1990: renewable resources should provide a sustainable yield (the rate of harvest should not exceed the rate of regeneration); for non-renewable resources there should be equivalent development of renewable substitutes; waste generation should not exceed the assimilative capacity of the environment.

In 2019, a summary for policymakers of the largest, most comprehensive study to date of biodiversity and ecosystem services was published by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services. It recommended that human civilization will need a transformative change, including sustainable agriculture, reductions in consumption and waste, fishing quotas and collaborative water management.

Environmental problems associated with industrial agriculture and agribusiness are now being addressed through approaches such as sustainable agriculture, organic farming and more sustainable business practices. At the local level there are various movements working towards sustainable food systems which may include less meat consumption, local food production, slow food, sustainable gardening, and organic gardening. The environmental effects of different dietary patterns depend on many factors, including the proportion of animal and plant foods consumed and the method of food production.

As global population and affluence have increased, so has the use of various materials increased in volume, diversity, and distance transported. By 2050, humanity could consume an estimated 140 billion tons of minerals, ores, fossil fuels and biomass per year (three times its current amount) unless the economic growth rate is decoupled from the rate of natural resource consumption.

Sustainable use of materials has targeted the idea of dematerialization, converting the linear path of materials (extraction, use, disposal in landfill) to a circular material flow that reuses materials as much as possible, much like the cycling and reuse of waste in nature. This way of thinking is expressed in the concept of circular economy, which employs reuse, sharing, repair, refurbishment, remanufacturing and recycling to create a closed-loop system, minimizing the use of resource inputs and the creation of waste, pollution and carbon emissions. The European Commission has adopted an ambitious Circular Economy Action Plan in 2020, which aims at making sustainable products the norm in the EU.

Improving on economic and social aspects

It has been suggested that because of the rural poverty and overexploitation, environmental resources should be treated as important economic assets, called natural capital. Economic development has traditionally required a growth in the gross domestic product. This model of unlimited personal and GDP growth may be over. Sustainable development may involve improvements in the quality of life for many but may necessitate a decrease in resource consumption. "Growth" generally ignores the direct effect that the environment may have on social welfare, whereas "development" takes it into account.

As early as the 1970s, the concept of sustainability was used to describe an economy "in equilibrium with basic ecological support systems". Scientists in many fields have highlighted The Limits to Growth, and economists have presented alternatives, for example a 'steady-state economy', to address concerns over the impacts of expanding human development on the planet. In 1987, the economist Edward Barbier published the study The Concept of Sustainable Economic Development, where he recognized that goals of environmental conservation and economic development are not conflicting and can be reinforcing each other.

A World Bank study from 1999 concluded that based on the theory of genuine savings (defined as "traditional net savings less the value of resource depletion and environmental degradation plus the value of investment in human capital"), policymakers have many possible interventions to increase sustainability, in macroeconomics or purely environmental. Several studies have noted that efficient policies for renewable energy and pollution are compatible with increasing human welfare, eventually reaching a golden-rule steady state.

A meta review in 2002 looked at environmental and economic valuations and found a "lack of concrete understanding of what "sustainability policies" might entail in practice". A study concluded in 2007 that knowledge, manufactured and human capital (health and education) has not compensated for the degradation of natural capital in many parts of the world. It has been suggested that intergenerational equity can be incorporated into a sustainable development and decision making, as has become common in economic valuations of climate economics.

The World Business Council for Sustainable Development published a Vision 2050 document in 2021 to show "How business can lead the transformations the world needs". The vision states that "we envision a world in which 9+billion people can live well, within planetary boundaries, by 2050." This report was highlighted by The Guardian as "the largest concerted corporate sustainability action plan to date – include reversing the damage done to ecosystems, addressing rising greenhouse gas emissions and ensuring societies move to sustainable agriculture."

Barriers

There are many reasons why sustainability is so difficult to achieve. These reasons have the name sustainability barriers. Before addressing these barriers it is important to analyze and understand them. Some barriers arise from nature and its complexity ("everything is related"). Others arise from the human condition. One example is the value-action gap. This reflects the fact that people often do not act according to their convictions. Experts describe these barriers as intrinsic to the concept of sustainability.

Other barriers are extrinsic to the concept of sustainability. This means it is possible to overcome them. One way would be to put a price tag on the consumption of public goods. Some extrinsic barriers relate to the nature of dominant institutional frameworks. Examples would be where market mechanisms fail for public goods. Existing societies, economies, and cultures encourage increased consumption. There is a structural imperative for growth in competitive market economies. This inhibits necessary societal change.

Furthermore, there are several barriers related to the difficulties of implementing sustainability policies. There are trade-offs between the goals of environmental policies and economic development. Environmental goals include nature conservation. Development may focus on poverty reduction. There are also trade-offs between short-term profit and long-term viability. Political pressures generally favor the short term over the long term. So they form a barrier to actions oriented toward improving sustainability.

Barriers to sustainability may also reflect current trends. These could include consumerism and short-termism.

Conflicts, lack of international cooperation are also considered as a barrier to achieve sustainability. 61 scientists, including Michael Meeropol, Don Trent Jacobs and 24 organizations including Scientist Rebellion endorsed an appeal saying we can not stop the ecological crisis without stopping overconsumption and this is impossible as wars continue because GDP is directly linked to military potential.

Assessments and reactions

The concept of sustainable development has been and still is, subject to criticism, including the question of what is to be sustained in sustainable development. It has been argued that there is no such thing as sustainable use of a non-renewable resource, since any positive rate of exploitation will eventually lead to the exhaustion of earth's finite stock; this perspective renders the Industrial Revolution as a whole unsustainable.

The sustainable development debate is based on the assumption that societies need to manage three types of capital (economic, social, and natural), which may be non-substitutable and whose consumption might be irreversible. Natural capital can not necessarily be substituted by economic capital. While it is possible that we can find ways to replace some natural resources, it is much less likely that they will ever be able to replace ecosystem services, such as the protection provided by the ozone layer, or the climate stabilizing function of the Amazonian forest.

The concept of sustainable development has been criticized from different angles. While some see it as paradoxical (or an oxymoron) and regard development as inherently unsustainable, others are disappointed in the lack of progress that has been achieved so far. Part of the problem is that "development" itself is not consistently defined.

The vagueness of the Brundtland definition of sustainable development has been criticized as follows: The definition has "opened up the possibility of downplaying sustainability. Hence, governments spread the message that we can have it all at the same time, i.e. economic growth, prospering societies and a healthy environment. No new ethic is required. This so-called weak version of sustainability is popular among governments, and businesses, but profoundly wrong and not even weak, as there is no alternative to preserving the earth's ecological integrity."

Scholars have stated that sustainable development is open-ended, much critiqued as ambiguous, incoherent, and therefore easily appropriated.

Society and culture

Sustainable development goals

Sustainable development is the foundational concept of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Policies to achieve the SDGs are meant to cohere around this concept.

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, adopted by all United Nations (UN) members in 2015, created 17 world Sustainable Development Goals (abbr. SDGs). The aim of these global goals is "peace and prosperity for people and the planet" – while tackling climate change and working to preserve oceans and forests. The SDGs highlight the connections between the environmental, social and economic aspects of sustainable development. Sustainability is at the center of the SDGs, as the term sustainable development implies.

These goals are ambitious, and the reports and outcomes to date indicate a challenging path. Most, if not all, of the goals are unlikely to be met by 2030. Rising inequalities, climate change, and biodiversity loss are topics of concern threatening progress. The COVID-19 pandemic from 2020 to 2023 made these challenges worse, and some regions, such as Asia, have experienced significant setbacks during that time.

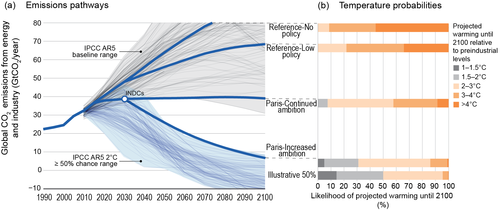

There are cross-cutting issues and synergies between the different goals; for example, for SDG 13 on climate action, the IPCC sees robust synergies with SDGs 3 (health), 7 (clean energy), 11 (cities and communities), 12 (responsible consumption and production) and 14 (oceans). On the other hand, critics and observers have also identified trade-offs between the goals, such as between ending hunger and promoting environmental sustainability. Furthermore, concerns have arisen over the high number of goals (compared to the eight Millennium Development Goals), leading to compounded trade-offs, a weak emphasis on environmental sustainability, and difficulties tracking qualitative indicators.

Education for sustainable development

Education for sustainable development (ESD) is a term officially used by the United Nations. It is defined as education practices that encourage changes in knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes to enable a more sustainable and just society for humanity. ESD aims to empower and equip current and future generations to meet their needs using a balanced and integrated approach to sustainable development's economic, social, and environmental dimensions.

Agenda 21 was the first international document that identified education as an essential tool for achieving sustainable development and highlighted areas of action for education. ESD is a component of measurement in an indicator for Sustainable Development Goal 12 (SDG) for "responsible consumption and production". SDG 12 has 11 targets, and target 12.8 is "By 2030, ensure that people everywhere have the relevant information and awareness for sustainable development and lifestyles in harmony with nature." 20 years after the Agenda 21 document was declared, the 'Future we want' document was proclaimed in the Rio+20 UN Conference on Sustainable Development, stating that "We resolve to promote education for sustainable development and to integrate sustainable development more actively into education beyond the Decade of Education for Sustainable Development."

One version of education for Sustainable Development recognizes modern-day environmental challenges. It seeks to define new ways to adjust to a changing biosphere, as well as engage individuals to address societal issues that come with them. In the International Encyclopedia of Education, this approach to education is seen as an attempt to "shift consciousness toward an ethics of life-giving relationships that respects the interconnectedness of man to his natural world" to equip future members of society with environmental awareness and a sense of responsibility to sustainability.

For UNESCO, education for sustainable development involves:

integrating key sustainable development issues into teaching and learning. This may include, for example, instruction about climate change, disaster risk reduction, biodiversity, and poverty reduction and sustainable consumption. It also requires participatory teaching and learning methods that motivate and empower learners to change their behaviours and take action for sustainable development. ESD consequently promotes competencies like critical thinking, imagining future scenarios and making decisions in a collaborative way.

The Thessaloniki Declaration, presented at the "International Conference on Environment and Society: Education and Public Awareness for Sustainability" by UNESCO and the Government of Greece (December 1997), highlights the importance of sustainability not only with regards to the natural environment, but also with "poverty, health, food security, democracy, human rights, and peace".