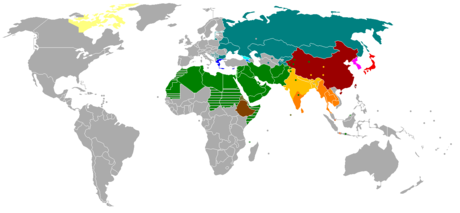

Current distribution of the Latin script.

Countries where the Latin script is the sole main script

Countries where Latin co-exists with other scripts

Latin-script

alphabets are sometimes extensively used in areas coloured grey due to

the use of unofficial second languages, such as French in Algeria and

English in Egypt, and to Latin transliteration of the official script,

such as pinyin in China.

This article discusses the geographic spread of the Latin script throughout history, from its archaic beginnings in Latium to the dominant writing system on Earth in modernity.

The Latin letters' ancestors are found in the Etruscan, Greek and ultimately Phoenician alphabet. As the Roman Empire expanded in late antiquity, the Latin script and language spread along with its conquests, and remained in use in Italy, Iberia and Western Europe after the Western Roman Empire's disappearance. During the early and high Middle Ages, the script was spread by Christian missionaries and rulers, replacing earlier writing systems on the British Isles, Central and Northern Europe.

In the Age of Discovery, the first wave of European colonisation saw the adoption of Latin alphabets primarily in the Americas and Australia, whereas sub-Sahara Africa, Southeast Asia and the Pacific were Latinised in the period of New Imperialism. Realising that Latin was now the most widely used script on Earth, the Bolsheviks made efforts to develop and establish Latin alphabets for all languages in the lands they controlled in Eastern Europe, North and Central Asia. However, after the Soviet Union's first three decades, these were gradually abandoned in the 1930s in favour of Cyrillic. Some post-Soviet Turkic-majority states decided to reintroduce the Latin script in the 1990s after the 1928 example of Turkey. In the early 21st century, non-Latin writing systems were still only prevalent in most parts of the Middle East and North Africa and former Soviet regions, most countries in Indochina, South and East Asia, Ethiopia and some Balkan countries in Europe.

Protohistory

The Marsiliana tablet (c. 700 BCE), containing the earliest known Etruscan abecedarium.

The Latin script originated in archaic antiquity in the Latium region in central Italy. It is generally held that the Latins, one of many ancient Italic tribes, adopted the western variant of the Greek alphabet in the 7th century BCE from Cumae, a Greek colony in southern Italy – making the early Latin alphabet one among several Old Italic alphabets emerging at the time. The early Latin script was heavily influenced by the then regionally dominant Etruscan civilization; the Latins ultimately adopted 22 of the original 26 Etruscan letters, which derived from Western Greek as well.

Antiquity

Along with the Latin language, the Latin writing system first spread over the Italian Peninsula with the rise of the Roman Republic, especially after 350 BCE. For example, the region of Umbria seems to have switched from its own script in the 2nd century BCE to Latin in the 1st. Next were the lands surrounding the Western Mediterranean Sea: Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica, Africa Proconsularis, Numidia, Hispania, and Gallia Transalpina. This continued during the early period of expansion of the Roman Empire (c. 27 BCE – 117 CE) in regions such as Illyria, Rhaetia, Noricum, Dacia, Gaul, Belgica, western Germania, and Britannia. The eastern half of the Empire, including Greece, Macedonia, Asia Minor, the Levant, and Egypt, continued to use Greek as a lingua franca, but Latin was widely spoken in the western half, and as the western Romance languages evolved out of Latin, they continued to use and adapt the Latin alphabet. Despite the loss of the Latin-speaking Western provinces, the Byzantine Empire maintained Latin as its legal language, under 6th-century emperor Justinian I producing the vast Corpus Juris Civilis that would have a major impact on Western European legal history from c. 1100 to 1900.

The Germanic peoples that invaded and gradually settled the Western

Roman Empire between the 5th and 8th centuries, most notably the Franks (first as the Merovingian script, later the Carolingian minuscule), adopted the Latin script and spread it further.

Middle Ages

Latin Christianisation of Western, Central and Northern Europe

Example of Carolingian minuscule from a 10th-century manuscript.

With the spread of Western Christianity during the Middle Ages, the Latin alphabet was gradually adopted by the peoples of Northern Europe who spoke Celtic languages (displacing the Ogham alphabet since the 5th century) or Germanic languages (displacing earlier Runic alphabets since the 8th century) or Baltic languages, as well as by the speakers of several Uralic languages, most notably Hungarian, Finnish and Estonian. The Latin script was introduced to Scandinavia in the 9th century, first in Denmark. It reached Norway during the 11th-century Christianisation, but in two different forms: the Anglo-Saxon Insular script in Western Norway and the Carolingian minuscule in Eastern Norway.

Slavic languages

The Latin script also came into use for writing the West Slavic languages and several South Slavic languages such as Slovene and Croatian, as the people who spoke them adopted Roman Catholicism. The speakers of East Slavic languages generally adopted Cyrillic along with Orthodox Christianity. The Serbian language has come to use both scripts, whilst the Southeastern Slavic Bulgarian and Macedonian languages have maintained Cyrillic only.

Early modern period

As late as 1500, the Latin script was limited primarily to the languages spoken in Western, Northern, and Central Europe, Iberia and Italy. The Orthodox Christian Slavs of Eastern and Southeastern Europe mostly used Cyrillic, and the Greek alphabet was in use by Greek-speakers around the eastern Mediterranean. The Arabic script was widespread within Islamdom, both among Arabs and non-Arab nations like the Iranians, Indonesians, Malays, and Turkic peoples, as well as amongst Arab Christians. Most of the rest of Asia used a variety of Brahmic alphabets or the Chinese script.

Since the 15th and especially 16th centuries, the Latin script has spread around the world, to the Americas, Oceania, and parts of Asia and Africa (until about 1880 mostly limited to the coastal areas), and the Pacific with European colonisation, along with the Spanish, Portuguese, English, French, and Dutch languages.

Americas

In an effort to Christianise and 'civilise' the Mayans, the Roman Catholic bishop Diego de Landa of Yucatán ordered the burning of most Maya codices in July 1562, and with it the near destruction of the Mayan hieroglyphic script.

He then rewrote the history of the Mayans in Spanish, and the Mayan

language was romanised, leading to an enormous loss in culture.

Latin letters served as the basis for the forms of the Cherokee syllabary developed by Sequoyah in the late 1810s and early 1820s; however, the sound values are completely different.

Southeast Asia and Pacific

The Latin script was introduced for many Austronesian languages, including the languages of the Philippines and the Malaysian and Indonesian languages, replacing earlier Arabic and indigenous Brahmic alphabets.

During the Dutch rule on Formosa (1624–1662), the island currently known as Taiwan, the Siraya language was given a Sinckan Latin alphabet by the Dutch, which lasted until the 19th century.

19th century

Africa

The Scramble for Africa

(1881–1914), meaning the rapid occupation, colonisation and annexation

of inland Africa by European powers, went hand in hand with the spread

of literacy amongst native Africans, as the Latin script was introduced

where there were other writing systems or none. Until the early 19th

century, the Berber peoples in North Africa had two systems: originally Tifinagh, and, following the spread of Islam, the Arabic script as well. French colonists, particularly missionaries and army linguists, developed a Berber Latin alphabet to make communication easier, especially for the Kabyle people in French Algeria.

Since no great body of Berber literature existed, and the colonisers

greatly helped improve literacy rates, the romanisation received much

support, more so after Algerian independence (1962) when the

French-educated Kabyle intelligentsia began to stimulate the transition

and especially since the establishment of a standard transcription for

Kabylie in 1970. Similar French attempts to Latinise the Arabic language

met much more resistance, were unsuccessful and eventually abandoned.

Romania

As a Romance language, Romanian continued to be written in Latin script until the Council of Florence in 1439.[10] Increasingly influenced by Russia as the Greek Byzantine Empire declined and was gradually conquered by the Ottoman Empire in the 15th century, the Eastern Orthodox Church had begun promoting the Slavic Cyrillic. In the 19th century, the Romanians returned to the Latin alphabet under the influence of nationalism. The linguist Ion Heliade Rădulescu

first proposed a simplified version of Cyrillic in 1829, but in 1838,

he introduced a mixed alphabet containing 19 Cyrillic and 10 Latin

letters, and an [i] and [o] that could be both. This 'transitional

orthography' was widely used until the official adoption of a completely

Latin Romanian alphabet in Wallachia (1860) and Moldavia (1863), that were gradually united since 1859 to become the Kingdom of Romania in 1881. Romanian intellectuals in Transylvania, then still part of Austria-Hungary,

and scholars in Wallachia-Moldavia agreed to cleanse the language from

all non-Latin elements (Greek, Magyar, Slavic, and Ottoman), and to

emulate French wherever needed.

Russian Empire

The Lithuanian press ban

in action: two issues of the same popular prayer book. The Latin left

one was illegal, the right Cyrillic one was legal and paid for by the

government.

Tsar Nicholas I (r. 1826–1855) of the Russian Empire introduced a policy of Russification, including Cyrillisation. From the 1840s on, Russia considered introducing the Cyrillic script for spelling the Polish language, with the first school books printed in the 1860s.

The imperial government's attempts failed, however: the Polish

population put up a tough resistance, as it saw its language as

expressed in its Latin alphabet as a source of national pride, and

threatened to rebel if it were to be abolished.

The initially successfully enacted Lithuanian press ban

(1865–1904) outlawed the use of Latin script, whilst encouraging

writing Lithuanian texts in Cyrillic. Resistance grew as time went on: Lithuanian books were smuggled into the country, mainly from Lithuania Minor in East Prussia.

Although the Russian authorities tried to seize them, they could not

stop the rapid increase in forbidden titles from crossing the border.

The Lithuanian ban, lifted in 1904, is widely felt to have stimulated

the Lithuanian national movement and embracing the Latin script, rather

than discouraging it.

Vietnam

A romanization of Vietnamese was codified in the 17th century by the French Jesuit missionary Alexandre de Rhodes (1591–1660), based on works of the early 16th-century Portuguese missionaries Gaspar do Amaral and António Barbosa. This Vietnamese alphabet (chữ quốc ngữ

or "national script") was gradually expanded from its initial domain in

Christian writing to become more popular among the general public,

which had previously used Chinese-based characters.

During the French protectorate

(1883–1945), colonial rulers made an effort to educate all Vietnamese,

and a simpler writing system was found more expedient for teaching and

communication with the general population. It was not until the

beginning of the 20th century that the romanized script came to

predominate written communication.

To further the process, Vietnamese written with the alphabet was made

obligatory for all public documents in 1910 by issue of a decree by the

French Résident Supérieur of the protectorate of Tonkin in northern Vietnam.

20th century

Albanian

Albanian used a variety of writing systems

since its first attestation in the 12th century, especially Latin (in

the north), Greek (in the south), Ottoman and Arabic (favoured by many

Muslims). Attempts at standardisation were made throughout the 19th

century, since 1879 led by the Society for the Publication of Albanian Writings, culminating in the 1908 Congress of Manastir

when a single Latin script, Bashkimi, was chosen for the whole

language. Although the newly adopted Albanian Latin alphabet symbolised a

break with Ottoman rule, some Islamist Kosovo Albanians objected

strongly against it, preferring to maintain the Arabic script that was

found in the Quran,

which they held sacred. However, nationalists maintained the Latin

alphabet was 'above religion' and therefore also acceptable to

non-Islamic and secular Albanians; they would win the argument.

Uyghur

The Uyghur language

in China used a Latin-derived alphabet created upon Pinyin spelling

conventions, but it was abolished in 1982 and the Arabic script was

restored.

Serbo-Croatian

A map showing the expansion of the use of Latin script in areas of former Yugoslavia, primarily amongst Croatians and Slovenes (Roman Catholics), Bosniaks (Bosnian Muslims) and Kosovars (Albanian Muslims). Cyrillic texts are dominant in areas primarily inhabited by Serbs, Montenegrins, and Macedonians (Eastern Orthodox Christians). This cultural boundary has existed since the dichotomy of the Greek East and Latin West.

Croatian linguist Ljudevit Gaj devised a uniform Latin alphabet for Croatian in 1835, while in 1818, Serbian linguist Vuk Karadžić had developed a Serbian Cyrillic alphabet. In the first half of the 19th century, the Illyrian movement

to unite all Southern Slavs (Yugoslavs) culturally, and perhaps also

politically, was quite strong, and efforts were made to create a unified

literary language that would set the standard for all Yugoslav

dialects. The Vienna Literary Agreement

(March 1850) between writers from Croatia, Serbia and one from Slovenia

was the most significant attempt, where some basic rules were agreed

upon. In the 1860s, Vuk's orthography gained acceptance in Serbia, while

a Yugoslav Academy of Sciences and Arts was founded in 1866 in Zagreb and the first 'Serbo-Croatian' grammar book by Pero Budmani was published in Croatia in 1867. In 1913, Jovan Skerlić proposed a compromise for a single writing system and dialect to create true language unity. After World War I, political unity was realised in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia, but an agreement on scriptural unity for its population was never reached. The post-war Titoist Federal People's Republic of Yugoslavia made another attempt at achieving linguistic unity, but the 1954 Novi Sad Agreement

only managed to get equality of Latin and Cyrillic, and an obligation

for all citizens to learn both alphabets. With the return of ethnic

nationalism in the 1980s, the two again became heavily associated with

particular variants of the Serbo-Croatian language and thus with

national identities. Exacerbated by the Yugoslav Wars

that led to the disintegration of Yugoslavia in the 1990s, nationalists

on all sides resumed insisting Croatian, Bosnian, Serbian and

Montenegrin were distinct languages in their own right, undermining the

project of Serbo-Croatian linguistic unity.

The Bosnian language was originally primarily expressed in the Cyrillic-type Bosančica since the 11th century (originally alongside the older Glagoljica), but it was gradually driven extinct in the 18th century after the Ottoman introduction of the Perso-Arabic script-type Arebica (15th–20th century). Eventually, most Bosnians adopted the Croatian-derived Latinica or Latin script –originally introduced by the Catholic Franciscans– in the course of the 20th century, standardised in the 1990s.

Middle East and North Africa

Mustafa Kemal Atatürk introduced the Latin script in Turkey in 1928.

In 1928, as part of Mustafa Kemal Atatürk's reforms, the new Republic of Turkey adopted the Turkish Latin alphabet for the Turkish language, replacing a modified Arabic alphabet.

In the 1930s and 1940s, the majority of Kurds replaced the Arabic script with two Latin alphabets. Although the only official Kurdish government, the Kurdistan Regional Government in northern Iraq,

uses an Arabic alphabet for public documents, the Latin Kurdish

alphabet remains widely used throughout the region by the majority of Kurdish speakers, especially in Turkey and Syria.

During the late 20th century decolonisation, Pan-Arabism and Arab nationalism

expressed themselves in anti-Western tendencies, including hostility

towards the Latin script. It was banned in some places such as Libya

after Moammar Gaddafi's 1969 coup, in favour of exclusive Arabic script.

Soviet Union

Since at least 1700, Russian intellectuals have sought to Latinise the Russian language in their desire for close relations with the West. The Bolsheviks had four goals: to break with Tsarism, to spread socialism to the whole world, to isolate the Muslim inhabitants of the Soviet Union from the Arabic-Islamic world and religion, and eradicate illiteracy through simplification. They concluded the Latin alphabet was the right tool to do so, and after seizing power during the Russian Revolution of 1917, they made plans to realise these ideals.

Although progress was slow at first, in 1926 the Turkic-majority

republics of the Soviet Union adopted the Latin script, giving a major

boost to reformers in neighbouring Turkey. When Mustafa Kemal Atatürk adopted the new Turkish Latin alphabet in 1928, this in turn encouraged the Soviet leaders to proceed.

The Commission to romanise the Russian alphabet completed its work in

mid-January 1930. But on 25 January 1930, General Secretary Joseph Stalin ordered the stop of the romanisation of Russian. The Latinisation of non-Slavic languages within the USSR continued until the late 1930s, however. Most of the Turkic-speaking peoples of the Soviet Union, including Tatars, Bashkirs, Azerbaijani or Azeri, Kazakh (1929–40), Kyrgyz and others, used the Latin-based Uniform Turkic alphabet in the 1930s; but, in the 1940s, all were replaced by Cyrillic.

Post-Soviet states

The Russian conquest of Transcaucasia in the 19th century split the Azerbaijani language community across two states, the other being Iran. The Soviet Union promoted development of the language, but set it back considerably with two successive script changes – from the Persian to Latin and then to the Cyrillic script – while Iranian Azerbaijanis continued to use the Persian as they always had. Despite the wide use of Azerbaijani in the Azerbaijan Soviet Socialist Republic, it did not become the official language of Azerbaijan until 1956.

After achieving independence from the Soviet Union 1991, the new

Republic of Azerbaijan decided to switch back to the Latin script.

Two other newly independent Turkic-speaking republics, Uzbekistan, and Turkmenistan, as well as Romanian-speaking Moldova on 31 August 1989, officially adopted Latin alphabets for their languages. In 1995, Uzbekistan ordered the Uzbek alphabet changed from a Russian-based Cyrillic script to a modified Latin alphabet, and in 1997, Uzbek became the sole language of state administration.

However, the government's implementation of the transition to Latin has

been rather slow, suffered several setbacks and as of 2017 has not yet

been completed. Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan, Iranian-speaking Tajikistan, and the breakaway region of Transnistria kept the Cyrillic alphabet, chiefly due to their close ties with Russia.

21st century

Kazakhstan

Kazakhstan's transition to the Latin script was welcomed by linguists and expats (Kazakh TV, November 2018).

Unlike its Turkic neighbours, Kazakhstan did not move towards

Latinisation after obtaining statehood in 1991. As of 2017 Latin is the

official script of Kazakhstan, replacing Cyrillic. This was motivated by

pragmatic reasons: the government was wary to alienate the country's

large Russian-speaking minority, and due to the economic crisis in the

early 1990s, a transition was considered fiscally unfeasable at the

time.

In 2006, President Nursultan Nazarbayev

requested the Ministry of Education and Science to examine the

experiences of Turkey, Azerbaijan, Turkmenistan and Uzbekistan, which

had all switched to Latin script in the 20th century. The ministry

reported in the summer of 2007 that a six-step plan, based primarily on

the Uzbekistan model, should be implemented over a 12-to-15-year period

at the cost of about $300 million. Aside from integrating Kazakhstan

into the global economy, officials have argued it would help the

development of a Kazakh national identity separate from Russia.

In 2007, Nazarbayev said the transformation of the Kazakh alphabet from

Cyrillic to Latin should not be rushed, as he noted: "For 70 years, the

Kazakhstanis read and wrote in Cyrillic. More than 100 nationalities

live in our state. Thus we need stability and peace. We should be in no

hurry in the issue of alphabet transformation".

In 2015, the Kazakh government announced that the Latin script would replace Cyrillic as the writing system for the Kazakh language by 2025.

In 2017, Nazarbayev said that "by the end of 2017, after consultation

with academics and representatives of the public, a single standard for

the new Kazakh alphabet

and script should be developed." Education specialists are to be

trained to teach the new alphabet and provide textbooks beginning in

2018. The romanisation policy is intended to modernise Kazakhstan and

increase international cooperation.

President Nazarbayev signed on February 19, 2018 an amendment to the

decree of October 26, 2017 No. 569 "On translating the Kazakh alphabet

from Cyrillic alphabet to the Latin script." The amended alphabet uses "Sh" and "Ch" for the Kazakh sounds "Ш" and "Ч" and eliminates the use of apostrophes.

Turkmenistan

The Turkmen Soviet Socialist Republic

employed a Latin alphabet from 1928 to 1940, when it was decreed that

all languages in the Soviet Union be written in Cyrillic. After gaining

independence in 1991, Turkmenistan was amongst several ex-Soviet states

seeking to reintroduce the Latin script. Although the authoritarian

president Saparmurat Niyazov,

leading Turkmenistan from 1985 to his death in 2006, announced a decree

on 12 April 1993 that formalised a new Turkmen Latin alphabet, the de facto

implementation has been slow and incomplete. The original 1993 alphabet

had 30 letters, but missed several sounds and did not fit the Turkmen

language, so several amendments were made in 1996. The first book in

Latin script was printed in 1995, but Turkmen language and literature

manuals were not available until 1999; Cyrillic manuals had been banned

before Latin ones were available. Although by 2011 the younger

generations were well-versed in the Turkmen Latin alphabet through the

education system, adults, including teachers, were not given any

official training programme and were expected to learn it by themselves

without state support.

Debates and proposals

Scripts in Europe in the 2010s.

Latin

Cyrillic

Latin & Cyrillic

Greek

Greek & Latin

Georgian

Armenian

|

Bulgaria

In 2001, Austrian slavistics professor Otto Kronsteiner recommended

that Bulgaria adopt the Latin script in order to facilitate the

country's accession to the European Union. This caused such a scandal that the Veliko Tarnovo University revoked the honorary degree it had previously awarded him (for supporting the Bulgarian viewpoint on the Macedonian language). For many Bulgarians,

the Cyrillic alphabet has become an important component of their

national identity, and great pride is taken in having introduced

Cyrillic into the EU in 2007.

However, in digital communication using computers and writing emails and SMS, the Latin script has been proposed to replace the Cyrillic. A Bulgarian Latin alphabet, the so-called shlyokavitsa,

is already often employed for convenience for emails and SMS messages.

Ciphers are used to denote Bulgarian sounds that cannot be represented

with a single Latin character (for example, a "4" represents a "ч" because they look alike and the Bulgarian word for the cardinal number four, чѐтири čѐtiri, starts with a "ч").

Kosovo

Despite initial resistance from Islamist Kosovo Albanians (who favoured the Arabic script) against the 1908 Congress of Manastir's resolution to adopt the Latin script to write the Albanian language in, Kosovo Albanians came to accept the Albanian Latin alphabet over the course of the early 20th century. Literacy amongst Kosovo Albanians increased from 26% in 1948 to 96.6% (men) and 87.5% (women) in 2007. The Kosovo Serbs have followed the practice of Cyrillic/Latin digraphia in the Republic of Serbia and continued to use both alphabets after the Kosovo War (1998–9) and the 2008 Kosovo declaration of independence.

Article 2 of the 2006 Law on the Use of Languages states that “Albanian

and Serbian and their alphabets are official languages of Kosovo and

have equal status in Kosovo institutions,” but fails to specify which

alphabets these are, as neither Latin nor Cyrillic is mentioned. This has often led the (ethnic Albanian-dominated) Kosovo authorities to exclusively use the Serb(o-Croatian) Latin alphabet

in its communication with the Serb minority, as it does with the

country's other five officially recognised minorities, especially the Bosniaks whose language is very similar to Serbian, but always written in Latin.

Although Kosovo Serbs may use either or both alphabets in everyday

life, some claim they've got the right to demand the authorities to

communicate with them in their preferred alphabet, and accuse the

government of violating the law.

The present attitudes of the Kosovar authorities have raised concerns

over the Latinisation of the Kosovo Serbs against their will, while the

government maintains it respects the legal rights of minorities.

Kyrgyzstan

Adopting the Latin script for the Kyrgyz language has been the subject of discussions in Kyrgyzstan

since attaining independence in the 1990s. However, unlike in the other

Turkic-dominated former Soviet republics in Central Asia, the issue did

not become prominent until its great neighbour Kazakhstan in September

2015 and April 2017 confirmed its previous announcements to Latinise the

closely related Kazakh language.

Before then, the largely Russian-speaking elite of the country saw no

reason to, nor did it seek to endanger its good-standing political and

economic relations with the Russian Federation. Amongst others, deputy

Kanybek Imanaliyev advocated a shift to Latin for 'the development of

contemporary technology, communication, education and science.' On the

other hand, due to financial constraints, he proposed to postpone the

transition to the 2030s or even 2040s. Because Russia is still a very

important financial supporter of Kyrgyzstan, other experts agreed it

would be unwise for Bishkek to make a move that would culturally

alienate Moscow. President Almazbek Atambayev stated in October 2017 that the country would not Latinise any time soon.

ULY

To the east of Kyrgyz language there it is a western China's language that historically was linked to the Kyrgyzstan's language: the Uighur language. Here recently has been created the Uyghur Latin script or ULY. This "Uyghur Latin Yëziqi" (ULY) is an auxiliary alphabet for the Uighur language based on the Latin script.

North Macedonia

The Macedonian language in its Cyrillic alphabet has been the official language of the Republic of Macedonia throughout the country and in its foreign relations since 1991. However, since the 2001 Albanian insurgency was ended by the Ohrid Agreement, the Constitution of Macedonia

has been amended (Amendment V) to mandate the co-official use of the

six minority languages and their respective alphabets in municipalities

in which more than 20% of an ethnic minority resides. The six minority

languages – Albanian, Turkish, Romani, Serbian, Bosnian and Aromanian –

are (with the exception of Serbian) always officially written in Latin

script in the municipalities where their speakers constitute a

significant minority or even majority. In addition, Macedonian is occasionally written in Latin, especially in advertising.

Mongolia

The Mongolian language

has been written in the Cyrillic script since 1940. There have been

talks to switch the language's alphabet to either the Latin script or

the traditional Mongolian script used in China's Inner Mongolia region.

Montenegro

There is ongoing discussion in Montenegro about how to label the "Montenegrin" language, which is mutually intelligible with the other standardised versions of Serbo-Croatian: Serbian, Croatian and Bosnian.

These debates focus on the perceived linguistic differences between

Montenegrin and related variants, but also on national and political

identification. Montenegro practices digraphia: there are two official Montenegrin alphabets, one Latin and one Cyrillic. In electoral campaigns after 2000, especially the 2006 independence referendum, Latin has come to symbolise closeness to Western countries, including Montenegro's historical ties to Venice, and independence from Serbia; on the other hand, Cyrillic is taken to signify unity with Serbia and closeness to the East.

In general, proponents of calling the language "Montenegrin" –

including the government – tend to favour the Latin script, whereas

supporters of "Serbian" prefer Cyrillic.

In June 2016, an incident in which top students in primary and

secondary schools for the first time since World War II received their

"Luca" diplomas – named after Njegoš's poem – printed in the Latin alphabet, sparked political controversy. The opposition Socialist People's Party (SNP) accused Education Minister Predrag Bošković

of "persecuting Cyrillic" and discriminating against pupils who use

this script. The SNP was unsuccessful in forcing the minister to resign.

The annual June reception of Latin-printed pupil's diplomas in schools

continued to cause pro-Serbian organisations including new small

opposition party True Montenegro

to claim Cyrillic users were being 'discriminated' against, while

Education Minister Damir Šehović stated that schools are obliged to

issue Cyrillic diplomas, but only at the request of pupils’ parents.

Serbia

Under the Constitution of Serbia of 2006, Cyrillic script is the only one in official use. Nonetheless the Latin script is widely used. In May 2017, Minister of Culture and Information Vladan Vukosavljević

proposed several measures to better support the Cyrillic script, which

was "in danger of falling into disuse". He said there wasn't any kind of

conspiracy going on against the Cyrillic alphabet, but rather that the

spirit of the times, historical circumstances and the decades-long

process of globalisation had gradually made Latin the world's dominant

script. "Especially young people in Serbia are now mostly turning to

Latin characters because of the media, the Internet and the logos of

world brands."

In August 2018, the Ministry of Culture proposed a law to that effect,

obliging government institutions to use Cyrillic under the threat of fines,

and setting up a Council for the Serbian Language to implement this

suggested language policy. The ministry claimed that indifference

towards which script to use was not “a culturally responsible position”,

and complained that some people had come to “use the Latin script as a

symbol of [their] openness and European affiliation”, arguing that Cyrillic was also one of the European Union's official writing systems and that "the EU is a community of peoples with their peculiarities."

Tatarstan (Russia)

In 1999, the Russian Republic of Tatarstan proposed to convert the Turkic Tatar language to Latin script in order to bring it into the modern world of the Internet.

There was opposition from both inside and outside Tatarstan, with

Tatars arguing it would threaten their national identity and to sever

their ties to the past. The Russian State Duma rejected the proposal. President Vladimir Putin said that a Tatar move from Cyrillic to Latin would 'threaten the unity of the Russian Federation'.

In 2002, Putin therefore enacted a law that made the use of Cyrillic

mandatory for all languages in all autonomous republics of Russia.

Ukraine

In March 2018, Foreign Minister of Ukraine Pavlo Klimkin

called for a discussion on the introduction of the Latin alphabet in

parallel usage with the traditional Cyrillic one in Ukraine. He did so

in response to the suggestion of Polish historian Ziemowit Szczerek.

Ukraine's parliamentary committee on science and education responded,

with first deputy chair Oleksandr Spivakovsky saying that today in

Ukraine there are other, more important issues to work on than a

transition to the Latin script. Similarly, philology professor Oleksandr

Ponomariv was skeptical whether a full transition to Latin would

benefit Ukraine, but did not rule out the parallel use of two alphabets.

He pointed to the fact that the Serbian language is also expressed in both a Cyrillic and a Latin alphabet.