A synthetic diamond or laboratory-grown diamond (LGD), also called a lab-grown, laboratory-created, man-made, artisan-created, artificial, or cultured diamond, is a diamond that is produced in a controlled technological process, in contrast to a naturally-formed diamond, which is created through geological processes and obtained by mining. Unlike diamond simulants (imitations of diamond made of superficially similar non-diamond materials), synthetic diamonds are composed of the same material as naturally formed diamonds—pure carbon crystallized in an isotropic 3D form—and have identical chemical and physical properties.

The maximal size of synthetic diamonds has increased dramatically in the 21st century. Before 2010, most synthetic diamonds were smaller than half a carat. Improvements in technology, plus the availability of larger diamond substrates, have led to synthetic diamonds up to 125 carats in 2025.

In 1797, English chemist Smithson Tennant demonstrated that diamonds are a form of carbon, and between 1879 and 1928, numerous claims of diamond synthesis were reported; most of these attempts were carefully analyzed, but none were confirmed. In the 1940s, systematic research of diamond creation began in the United States, Sweden and the Soviet Union, which culminated in the first reproducible synthesis in 1953. Further research activity led to the development of high pressure high temperature (HPHT) and chemical vapor deposition (CVD) methods of diamond production. These two processes still dominate synthetic diamond production. A third method in which nanometer-sized diamond grains are created in a detonation of carbon-containing explosives, known as detonation synthesis, entered the market in the late 1990s.

The properties of synthetic diamonds depend on the manufacturing process. Some have properties such as hardness, thermal conductivity and electron mobility that are superior to those of most naturally formed diamonds. Synthetic diamond is widely used in abrasives, in cutting and polishing tools and in heat sinks. Electronic applications of synthetic diamond are being developed, including high-power switches at power stations, high-frequency field-effect transistors and light-emitting diodes (LEDs). Synthetic diamond detectors of ultraviolet (UV) light and of high-energy particles are used at high-energy research facilities and are available commercially. Due to its unique combination of thermal and chemical stability, low thermal expansion and high optical transparency in a wide spectral range, synthetic diamond is becoming the most popular material for optical windows in high-power CO

2 lasers and gyrotrons. It is estimated that 98% of industrial-grade diamond demand is supplied with synthetic diamonds.

Both CVD and HPHT diamonds can be cut into gems, and various colors can be produced: clear white, yellow, brown, blue, green and orange. The advent of synthetic gems on the market created major concerns in the diamond trading business, as a result of which special spectroscopic devices and techniques have been developed to distinguish synthetic from natural diamonds.

History

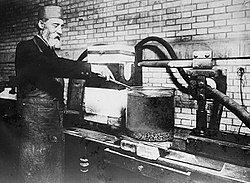

In the early stages of diamond synthesis, the founding figure of modern chemistry, Antoine Lavoisier, played a significant role. His groundbreaking discovery that a diamond's crystal lattice is similar to carbon's crystal structure paved the way for initial attempts to produce diamonds. After it was discovered that diamond was pure carbon in 1797, many attempts were made to convert various cheap forms of carbon into diamond. The earliest successes were reported by James Ballantyne Hannay in 1879 and by Ferdinand Frédéric Henri Moissan in 1893. Their method involved heating charcoal at up to 3,500 °C (6,330 °F) with iron inside a carbon crucible in a furnace. Whereas Hannay used a flame-heated tube, Moissan applied his newly developed electric arc furnace, in which an electric arc was struck between carbon rods inside blocks of lime. The molten iron was then rapidly cooled by immersion in water. The contraction generated by the cooling supposedly produced the high pressure required to transform graphite into diamond. Moissan published his work in a series of articles in the 1890s.

Many other scientists tried to replicate his experiments. Sir William Crookes claimed success in 1909. Otto Ruff claimed in 1917 to have produced diamonds up to 7 mm (0.28 in) in diameter, but later retracted his statement. In 1926, Dr. J. Willard Hershey of McPherson College replicated Moissan's and Ruff's experiments, producing a synthetic diamond. Despite the claims of Moissan, Ruff, and Hershey, other experimenters were unable to reproduce their synthesis.

The most definitive replication attempts were performed by Sir Charles Algernon Parsons. A prominent scientist and engineer known for his invention of the steam turbine, he spent about 40 years (1882–1922) and a considerable part of his fortune trying to reproduce the experiments of Moissan and Hannay, but also adapted processes of his own. Parsons was known for his painstakingly accurate approach and methodical record keeping; all his resulting samples were preserved for further analysis by an independent party. He wrote a number of articles—some of the earliest on HPHT diamond—in which he claimed to have produced small diamonds. However, in 1928, he authorized Dr. C. H. Desch to publish an article in which he stated his belief that no synthetic diamonds (including those of Moissan and others) had been produced up to that date. He suggested that most diamonds that had been produced up to that point were likely synthetic spinel.

ASEA

The first known (but initially not reported) diamond synthesis was achieved on February 16, 1953, in Stockholm by ASEA (Allmänna Svenska Elektriska Aktiebolaget), Sweden's major electrical equipment manufacturing company. Starting in 1942, ASEA employed a team of five scientists and engineers as part of a top-secret diamond-making project code-named QUINTUS. The team used a bulky split-sphere apparatus designed by Baltzar von Platen and Anders Kämpe. Pressure was maintained within the device at an estimated 8.4 GPa (1,220,000 psi) and a temperature of 2,400 °C (4,350 °F) for an hour. A few small diamonds were produced, but not of gem quality or size.

Due to questions on the patent process and the reasonable belief that no other serious diamond synthesis research occurred globally, the board of ASEA opted against publicity and patent applications. Thus the announcement of the ASEA results occurred shortly after the GE press conference of February 15, 1955.

GE diamond project

In 1941, an agreement was made between the General Electric (GE), Norton and Carborundum companies to further develop diamond synthesis. They were able to heat carbon to about 3,000 °C (5,430 °F) under a pressure of 3.5 gigapascals (510,000 psi) for a few seconds. Soon thereafter, the Second World War interrupted the project. It was resumed in 1951 at the Schenectady Laboratories of GE, and a high-pressure diamond group was formed with Francis P. Bundy and H. M. Strong. Tracy Hall and others joined the project later.

The Schenectady group improved on the anvils designed by Percy Bridgman, who received a Nobel Prize in Physics for his work in 1946. Bundy and Strong made the first improvements, then more were made by Hall. The GE team used tungsten carbide anvils within a hydraulic press to squeeze the carbonaceous sample held in a catlinite container, the finished grit being squeezed out of the container into a gasket. The team recorded diamond synthesis on one occasion, but the experiment could not be reproduced because of uncertain synthesis conditions, and the diamond was later shown to have been a natural diamond used as a seed.

Hall achieved the first commercially successful synthesis of diamond on December 16, 1954, and this was announced on February 15, 1955. His breakthrough came when he used a press with a hardened steel toroidal "belt" strained to its elastic limit wrapped around the sample, producing pressures above 10 GPa (1,500,000 psi) and temperatures above 2,000 °C (3,630 °F). The press used a pyrophyllite container in which graphite was dissolved within molten nickel, cobalt or iron. Those metals acted as a "solvent-catalyst", which both dissolved carbon and accelerated its conversion into diamond. The largest diamond he produced was 0.15 mm (0.0059 in) across; it was too small and visually imperfect for jewelry, but usable in industrial abrasives. Hall's co-workers were able to replicate his work, and the discovery was published in the major journal Nature. He was the first person to grow a synthetic diamond with a reproducible, verifiable and well-documented process. He left GE in 1955, and three years later developed a new apparatus for the synthesis of diamond—a tetrahedral press with four anvils—to avoid violating a U.S. Department of Commerce secrecy order on the GE patent applications.

Further development

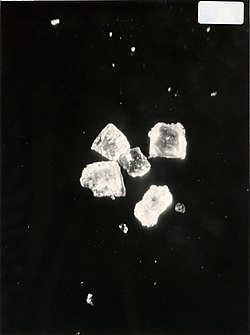

Synthetic gem-quality diamond crystals were first produced in 1970 by GE, then reported in 1971. The first successes used a pyrophyllite tube seeded at each end with thin pieces of diamond. The graphite feed material was placed in the center and the metal solvent (nickel) between the graphite and the seeds. The container was heated and the pressure was raised to about 5.5 GPa (800,000 psi). The crystals grow as they flow from the center to the ends of the tube, and extending the length of the process produces larger crystals. Initially, a week-long growth process produced gem-quality stones of around 5 mm (0.20 in) (1 carat or 0.2 g), and the process conditions had to be as stable as possible. The graphite feed was soon replaced by diamond grit because that allowed much better control of the shape of the final crystal.

The first gem-quality stones were always yellow to brown in color because of contamination with nitrogen. Inclusions were common, especially "plate-like" ones from the nickel. Removing all nitrogen from the process by adding aluminum or titanium produced colorless "white" stones, and removing the nitrogen and adding boron produced blue ones. Removing nitrogen also slowed the growth process and reduced the crystalline quality, so the process was normally run with nitrogen present.

Although the GE stones and natural diamonds were chemically identical, their physical properties were not the same. The colorless stones produced strong fluorescence and phosphorescence under short-wavelength ultraviolet light, but were inert under long-wave UV. Among natural diamonds, only the rarer blue gems exhibit these properties. Unlike natural diamonds, all the GE stones showed strong yellow fluorescence under X-rays. The De Beers Diamond Research Laboratory has grown stones of up to 25 carats (5.0 g) for research purposes. Stable HPHT conditions were kept for six weeks to grow high-quality diamonds of this size. For economic reasons, the growth of most synthetic diamonds is terminated when they reach a mass of 1 to 1.5 carats (200 to 300 mg).

In the 1950s, research started in the Soviet Union and the US on the growth of diamond by pyrolysis of hydrocarbon gases at the relatively low temperature of 800 °C (1,470 °F). This low-pressure process is known as chemical vapor deposition (CVD). William G. Eversole reportedly achieved vapor deposition of diamond over diamond substrate in 1953, but it was not reported until 1962. Diamond film deposition was independently reproduced by Angus and coworkers in 1968 and by Deryagin and Fedoseev in 1970. Whereas Eversole and Angus used large, expensive, single-crystal diamonds as substrates, Deryagin and Fedoseev succeeded in making diamond films on non-diamond materials (silicon and metals), which led to massive research on inexpensive diamond coatings in the 1980s.

From 2013, reports emerged of a rise in undisclosed synthetic melee diamonds (small round diamonds typically used to frame a central diamond or embellish a band) being found in set jewelry and within diamond parcels sold in the trade. Due to the relatively low cost of diamond melee, as well as relative lack of universal knowledge for identifying large quantities of melee efficiently, not all dealers have made an effort to test diamond melee to correctly identify whether it is of natural or synthetic origin. However, international laboratories are now beginning to tackle the issue head-on, with significant improvements in synthetic melee identification being made.

Manufacturing technologies

There are several methods used to produce synthetic diamonds. The original method uses high pressure and high temperature (HPHT) and is still widely used because of its relatively low cost. The process involves large presses that can weigh hundreds of tons to produce a pressure of 5 GPa (730,000 psi) at 1,500 °C (2,730 °F). The second method, using chemical vapor deposition (CVD), creates a carbon plasma over a substrate onto which the carbon atoms deposit to form diamond. Other methods include explosive formation (forming detonation nanodiamonds) and sonication of graphite solutions.

High pressure, high temperature

In the HPHT method, there are three main press designs used to supply the pressure and temperature necessary to produce synthetic diamond: the belt press, the cubic press and the split-sphere (BARS) press. Diamond seeds are placed at the bottom of the press. The internal part of the press is heated above 1,400 °C (2,550 °F) and melts the solvent metal. The molten metal dissolves the high purity carbon source, which is then transported to the small diamond seeds and precipitates, forming a large synthetic diamond.

The original GE invention by Tracy Hall uses the belt press wherein the upper and lower anvils supply the pressure load to a cylindrical inner cell. This internal pressure is confined radially by a belt of pre-stressed steel bands. The anvils also serve as electrodes providing electric current to the compressed cell. A variation of the belt press uses hydraulic pressure, rather than steel belts, to confine the internal pressure. Belt presses are still used today, but they are built on a much larger scale than those of the original design.

The second type of press design is the cubic press. A cubic press has six anvils which provide pressure simultaneously onto all faces of a cube-shaped volume. The first multi-anvil press design was a tetrahedral press, using four anvils to converge upon a tetrahedron-shaped volume. The cubic press was created shortly thereafter to increase the volume to which pressure could be applied. A cubic press is typically smaller than a belt press and can more rapidly achieve the pressure and temperature necessary to create synthetic diamond. However, cubic presses cannot be easily scaled up to larger volumes: the pressurized volume can be increased by using larger anvils, but this also increases the amount of force needed on the anvils to achieve the same pressure. An alternative is to decrease the surface area to volume ratio of the pressurized volume, by using more anvils to converge upon a higher-order platonic solid, such as a dodecahedron. However, such a press would be complex and difficult to manufacture.

The BARS apparatus is claimed to be the most compact, efficient, and economical of all the diamond-producing presses. In the center of a BARS device, there is a ceramic cylindrical "synthesis capsule" of about 2 cm3 (0.12 cu in) in size. The cell is placed into a cube of pressure-transmitting material, such as pyrophyllite ceramics, which is pressed by inner anvils made from cemented carbide (e.g., tungsten carbide or VK10 hard alloy). The outer octahedral cavity is pressed by 8 steel outer anvils. After mounting, the whole assembly is locked in a disc-type barrel with a diameter about 1 m (3 ft 3 in). The barrel is filled with oil, which pressurizes upon heating, and the oil pressure is transferred to the central cell. The synthesis capsule is heated up by a coaxial graphite heater, and the temperature is measured with a thermocouple.

Chemical vapor deposition

Chemical vapor deposition is a method by which diamond can be grown from a hydrocarbon gas mixture. Since the early 1980s, this method has been the subject of intensive worldwide research. Whereas the mass production of high-quality diamond crystals make the HPHT process the more suitable choice for industrial applications, the flexibility and simplicity of CVD setups explain the popularity of CVD growth in laboratory research. The advantages of CVD diamond growth include the ability to grow diamond over large areas and on various substrates, and the fine control over the chemical impurities and thus properties of the diamond produced. Unlike HPHT, CVD process does not require high pressures, as the growth typically occurs at pressures under 27 kPa (3.9 psi).

The CVD growth involves substrate preparation, feeding varying amounts of gases into a chamber and energizing them. The substrate preparation includes choosing an appropriate material and its crystallographic orientation; cleaning it, often with a diamond powder to abrade a non-diamond substrate; and optimizing the substrate temperature (about 800 °C (1,470 °F)) during the growth through a series of test runs. Moreover, optimizing the gas mixture composition and flow rates is paramount to ensure uniform and high-quality diamond growth. The gases always include a carbon source, typically methane, and hydrogen with a typical ratio of 1:99. Hydrogen is essential because it selectively etches off non-diamond carbon. The gases are ionized into chemically active radicals in the growth chamber using microwave power, a hot filament, an arc discharge, a welding torch, a laser, an electron beam, or other means.

During the growth, the chamber materials are etched off by the plasma and can incorporate into the growing diamond. In particular, CVD diamond is often contaminated by silicon originating from the silica windows of the growth chamber or from the silicon substrate. Therefore, silica windows are either avoided or moved away from the substrate. Boron-containing species in the chamber, even at very low trace levels, also make it unsuitable for the growth of pure diamond.

Detonation of explosives

Diamond nanocrystals (5 nm (2.0×10−7 in) in diameter) can be formed by detonating certain carbon-containing explosives in a metal chamber. These are called "detonation nanodiamonds". During the explosion, the pressure and temperature in the chamber become high enough to convert the carbon of the explosives into diamond. Being immersed in water, the chamber cools rapidly after the explosion, suppressing conversion of newly produced diamond into more stable graphite. In a variation of this technique, a metal tube filled with graphite powder is placed in the detonation chamber. The explosion heats and compresses the graphite to an extent sufficient for its conversion into diamond. The product is always rich in graphite and other non-diamond carbon forms, and requires prolonged boiling in hot nitric acid (about 1 day at 250 °C (482 °F)) to dissolve them. The recovered nanodiamond powder is used primarily in polishing applications. It is mainly produced in China, Russia and Belarus, and started reaching the market in bulk quantities by the early 2000s.

Ultrasound cavitation

Micron-sized diamond crystals can be synthesized from a suspension of graphite in organic liquid at atmospheric pressure and room temperature using ultrasonic cavitation. The diamond yield is about 10% of the initial graphite weight. The estimated cost of diamond produced by this method is comparable to that of the HPHT method but the crystalline perfection of the product is significantly worse for the ultrasonic synthesis. This technique requires relatively simple equipment and procedures, and has been reported by two research groups, but had no industrial use as of 2008. Numerous process parameters, such as preparation of the initial graphite powder, the choice of ultrasonic power, synthesis time and the solvent, were not optimized, leaving a window for potential improvement of the efficiency and reduction of the cost of the ultrasonic synthesis.

Crystallization inside liquid metal

In 2024, scientists announced a method that utilizes injecting methane and hydrogen gases onto a liquid metal alloy of gallium, iron, nickel and silicon (77.25/11.00/11.00/0.25 ratio) at approximately 1,025 °C to crystallize diamond at 1 atmosphere of pressure. The crystallization is a 'seedless' process, which further separates it from conventional high-pressure and high-temperature or chemical vapor deposition methods. Injection of methane and hydrogen results in a diamond nucleus after around 15 minutes and eventually a continuous diamond film after around 150 minutes.

Properties

Traditionally, the absence of crystal flaws is considered to be the most important quality of a diamond. Purity and high crystalline perfection make diamonds transparent and clear, whereas its hardness, optical dispersion (luster), and chemical stability (combined with marketing), make it a popular gemstone. High thermal conductivity is also important for technical applications. Whereas high optical dispersion is an intrinsic property of all diamonds, their other properties vary depending on how the diamond was created.

Crystallinity

Diamond can be one single, continuous crystal or it can be made up of many smaller crystals (polycrystal). Large, clear and transparent single-crystal diamonds are typically used as gemstones. Polycrystalline diamond (PCD) consists of numerous small grains, which are easily seen by the naked eye through strong light absorption and scattering; it is unsuitable for gems and is used for industrial applications such as mining and cutting tools. Polycrystalline diamond is often described by the average size (or grain size) of the crystals that make it up. Grain sizes range from nanometers to hundreds of micrometers, usually referred to as "nanocrystalline" and "microcrystalline" diamond, respectively.

Hardness

The hardness of diamond is 10 on the Mohs scale of mineral hardness, the hardest known material on this scale. Diamond is also the hardest known natural material for its resistance to indentation. The hardness of synthetic diamond depends on its purity, crystalline perfection and orientation: hardness is higher for flawless, pure crystals oriented to the direction (along the longest diagonal of the cubic diamond lattice). Nanocrystalline diamond produced through CVD diamond growth can have a hardness ranging from 30% to 75% of that of single crystal diamond, and the hardness can be controlled for specific applications. Some synthetic single-crystal diamonds and HPHT nanocrystalline diamonds (see hyperdiamond) are harder than any known natural diamond.

Impurities and inclusions

Every diamond contains atoms other than carbon in concentrations detectable by analytical techniques. Those atoms can aggregate into macroscopic phases called inclusions. Impurities are generally avoided, but can be introduced intentionally as a way to control certain properties of the diamond. Growth processes of synthetic diamond, using solvent-catalysts, generally lead to formation of a number of impurity-related complex centers, involving transition metal atoms (such as nickel, cobalt or iron), which affect the electronic properties of the material.

For instance, pure diamond is an electrical insulator, but diamond with boron added is an electrical conductor (and, in some cases, a superconductor), allowing it to be used in electronic applications. Nitrogen impurities hinder movement of lattice dislocations (defects within the crystal structure) and put the lattice under compressive stress, thereby increasing hardness and toughness.

Thermal conductivity

The thermal conductivity of CVD diamond ranges from tens of W/m2K to more than 2000 W/m2K, depending on the defects, grain boundary structures. As the growth of diamond in CVD, the grains grow with the film thickness, leading to a gradient thermal conductivity along the film thickness direction.

Unlike most electrical insulators, pure diamond is an excellent conductor of heat because of the strong covalent bonding

within the crystal. The thermal conductivity of pure diamond is the

highest of any known solid. Single crystals of synthetic diamond

enriched in 12

C (99.9%), isotopically pure diamond, have the highest thermal conductivity

of any material, 30 W/cm·K at room temperature, 7.5 times higher than

that of copper. Natural diamond's conductivity is reduced by 1.1% by the

13

C naturally present, which acts as an inhomogeneity in the lattice.

Diamond's thermal conductivity is made use of by jewelers and gemologists who may employ an electronic thermal probe to separate diamonds from their imitations. These probes consist of a pair of battery-powered thermistors mounted in a fine copper tip. One thermistor functions as a heating device while the other measures the temperature of the copper tip: if the stone being tested is a diamond, it will conduct the tip's thermal energy rapidly enough to produce a measurable temperature drop. This test takes about 2–3 seconds.

Industrial applications

Machining and cutting tools

Most industrial applications of synthetic diamond have long been associated with their hardness; this property makes diamond the ideal material for machine tools and cutting tools. As the hardest known naturally occurring material, diamond can be used to polish, cut, or wear away any material, including other diamonds. Common industrial applications of this ability include diamond-tipped drill bits and saws, and the use of diamond powder as an abrasive. These are by far the largest industrial applications of synthetic diamond. While natural diamond is also used for these purposes, synthetic HPHT diamond is more popular, mostly because of better reproducibility of its mechanical properties. Diamond is not suitable for machining ferrous alloys at high speeds, as carbon is soluble in iron at the high temperatures created by high-speed machining, leading to greatly increased wear on diamond tools compared to alternatives.

The usual form of diamond in cutting tools is micron-sized grains dispersed in a metal matrix (usually cobalt) sintered onto the tool. This is typically referred to in industry as polycrystalline diamond (PCD). PCD-tipped tools can be found in mining and cutting applications. For the past fifteen years, work has been done to coat metallic tools with CVD diamond, and though the work shows promise, it has not significantly replaced traditional PCD tools.

Thermal conductor

Most materials with high thermal conductivity are also electrically conductive, such as metals. In contrast, pure synthetic diamond has high thermal conductivity, but negligible electrical conductivity. This combination is invaluable for electronics where diamond is used as a heat spreader for high-power laser diodes, laser arrays and high-power transistors. Efficient heat dissipation prolongs the lifetime of those electronic devices, and the devices' high replacement costs justify the use of efficient, though relatively expensive, diamond heat sinks. In semiconductor technology, synthetic diamond heat spreaders prevent silicon and other semiconducting devices from overheating.

Optical material

Diamond is hard, chemically inert, and has high thermal conductivity and a low coefficient of thermal expansion. These properties make diamond superior to any other existing window material used for transmitting infrared and microwave radiation. Therefore, synthetic diamond is starting to replace zinc selenide as the output window of high-power CO2 lasers and gyrotrons. Those synthetic polycrystalline diamond windows are shaped as disks of large diameters (about 10 cm for gyrotrons) and small thicknesses (to reduce absorption) and can only be produced with the CVD technique. Single crystal slabs of dimensions of length up to approximately 10 mm are becoming increasingly important in several areas of optics including heatspreaders inside laser cavities, diffractive optics and as the optical gain medium in Raman lasers. Recent advances in the HPHT and CVD synthesis techniques have improved the purity and crystallographic structure perfection of single-crystalline diamond enough to replace silicon as a diffraction grating and window material in high-power radiation sources, such as synchrotrons. Both the CVD and HPHT processes are also used to create designer optically transparent diamond anvils as a tool for measuring electric and magnetic properties of materials at ultra high pressures using a diamond anvil cell.

Electronics

Synthetic diamond has potential uses as a semiconductor, because it can be doped with impurities like boron and phosphorus. Since these elements contain one more or one fewer valence electron than carbon, they turn synthetic diamond into p-type or n-type semiconductor. Making a p–n junction by sequential doping of synthetic diamond with boron and phosphorus produces light-emitting diodes (LEDs) producing UV light of 235 nm. Another useful property of synthetic diamond for electronics is high carrier mobility, which reaches 4500 cm2/(V·s) for electrons in single-crystal CVD diamond. High mobility is favorable for high-frequency operation and field-effect transistors made from diamond have already demonstrated promising high-frequency performance above 50 GHz. The wide band gap of diamond (5.5 eV) gives it excellent dielectric properties. Combined with the high mechanical stability of diamond, those properties are being used in prototype high-power switches for power stations.

Synthetic diamond transistors have been produced in the laboratory. They remain functional at much higher temperatures than silicon devices, and are resistant to chemical and radiation damage. While no diamond transistors have yet been successfully integrated into commercial electronics, they are promising for use in exceptionally high-power situations and hostile non-oxidizing environments.

Synthetic diamond is already used as radiation detection device. It is radiation hard and has a wide bandgap of 5.5 eV (at room temperature). Diamond is also distinguished from most other semiconductors by the lack of a stable native oxide. This makes it difficult to fabricate surface MOS devices, but it does create the potential for UV radiation to gain access to the active semiconductor without absorption in a surface layer. Because of these properties, it is employed in applications such as the BaBar detector at the Stanford Linear Accelerator and BOLD (Blind to the Optical Light Detectors for VUV solar observations). A diamond VUV detector recently was used in the European LYRA program.

Conductive CVD diamond is a useful electrode under many circumstances. Photochemical methods have been developed for covalently linking DNA to the surface of polycrystalline diamond films produced through CVD. Such DNA-modified films can be used for detecting various biomolecules, which would interact with DNA thereby changing electrical conductivity of the diamond film. In addition, diamonds can be used to detect redox reactions that cannot ordinarily be studied and in some cases degrade redox-reactive organic contaminants in water supplies. Because diamond is mechanically and chemically stable, it can be used as an electrode under conditions that would destroy traditional materials. As an electrode, synthetic diamond can be used in waste water treatment of organic effluents and the production of strong oxidants.

Gemstones

Synthetic diamonds for use as gemstones are grown by HPHT or CVD methods. The market share of synthetic jewelry-quality diamonds is growing as advances in technology allow for larger higher-quality synthetic production on a more economical scale. In 2013, synthetic diamonds accounted for 0.28% of rough diamonds produced for use as gemstones, and 2% of the gem-quality diamond market. In 2023, synthetic diamonds were 17% of the diamond jewelry market. They are available in yellow, pink, green, orange, blue and, to a lesser extent, colorless (or white). The yellow comes from nitrogen impurities in the manufacturing process, while the blue comes from boron. Other colors, such as pink or green, are achievable after synthesis using irradiation. Several companies also offer memorial diamonds grown using cremated remains.

In May 2015, a record was set for an HPHT colorless diamond at 10.02 carats. The faceted jewel was cut from a 32.2-carat stone that was grown in about 300 hours. By 2022, gem-quality diamonds of 16–20 carats were being produced.

Price

Around 2016, the price of synthetic diamond gemstones (e.g., 1-carat stones) began dropping "precipitously", by roughly 30% in one year, becoming clearly lower than that of mined diamond gems. In April 2022, CNN Business reported that a synthetic one-carat round diamond commonly used in engagement rings was up to 73% cheaper than a natural diamond with the same features, and that the number of engagement rings featuring a synthetic or a lab grown diamond had increased 63% compared to the previous year, while those sold with a natural diamond declined 25% in the same period. By the beginning of 2025 laboratory-grown diamonds had dropped in price by 74% since 2020, and prices were expected to continue decreasing. The drop was attributed largely to improvement in speed of laboratory growing of diamonds from weeks to hours.

Marketing and classification

Gem-quality diamonds grown in a lab can be chemically, physically, and optically identical to naturally occurring ones. The mined diamond industry has undertaken legal, marketing, and distribution countermeasures to try to protect its market from the emerging presence of synthetic diamonds, including price fixing. Synthetic diamonds can be distinguished by spectroscopy in the infrared, ultraviolet, or X-ray wavelengths. The DiamondView tester from De Beers uses UV fluorescence to detect trace impurities of nitrogen, nickel, or other metals in HPHT or CVD diamonds. Many other test instruments are available.

Diamond certification laboratories are equipped with instruments that can reliably distinguish laboratory-grown from natural diamonds. Several laboratories, including the Gemological Institute of America (GIA), the International Gemological Institute (IGI), and Gemological Science International (GSI), laser-inscribe the girdle of every lab-grown diamond they certify with their report number and an indication that the diamond is lab-grown. The inscription is invisible to the naked eye, but can be seen at 10x magnification.

In May 2018, De Beers announced that it would introduce a new jewelry brand called "Lightbox" that features synthetic diamonds, which was notable as the company was the world's largest diamond miner and had previously been an outspoken critic of synthetic diamonds. In July 2018, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission (FTC) approved a substantial revision to its Jewelry Guides, with changes that impose new rules on how the trade can describe diamonds and diamond simulants. The revised guidelines were substantially contrary to what had been advocated in 2016 by De Beers. The new guidelines remove the word "natural" from the definition of "diamond", thus including lab-grown diamonds within the scope of the definition of "diamond". The revised guide further states that "If a marketer uses 'synthetic' to imply that a competitor's lab-grown diamond is not an actual diamond, ... this would be deceptive." According to the new FTC guidelines, the GIA dropped the word "synthetic" from its certification process and report for lab-grown diamonds in July 2019.

Ethical and environmental considerations

Traditional diamond mining has led to human rights abuses in several countries in Africa and other diamond mining countries. The 2006 Hollywood movie Blood Diamond helped to publicize the problem. Consumer demand for synthetic diamonds has been increasing as customers look for ethically sound and cheaper stones.

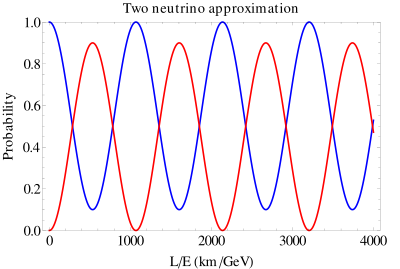

![{\displaystyle P_{\alpha \rightarrow \beta ,\alpha \neq \beta }=\sin ^{2}(2\theta )\,\sin ^{2}\left({\frac {\Delta m^{2}L}{4E}}\right)\quad {\text{ [natural units] .}}}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/9f79118b2f59fb1eacf6a4db2dc97e35791e7ce5)

![{\displaystyle P_{\alpha \rightarrow \beta ,\alpha \neq \beta }=\sin ^{2}(2\theta )\,\sin ^{2}\left(1.27\,{\frac {\Delta m^{2}L}{E}}\,{\frac {\rm {[eV^{2}]\,[km]}}{\rm {[GeV]}}}\right)~.}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/fba6e6d24df21172c4beaadf28f2d6ed0a845cec)