Psychology is the study of

mind and

behavior.

[1][2] It is an

academic discipline and an

applied science which seeks to understand individuals and groups by establishing general principles and researching specific cases.

[3][4] In this field, a professional

practitioner or researcher is called a

psychologist and can be classified as a

social,

behavioral, or

cognitive scientist. Psychologists attempt to understand the role of

mental functions in individual and

social behavior, while also exploring the

physiological and

biological processes that underlie cognitive functions and behaviors.

Psychologists explore concepts such as

perception,

cognition,

attention,

emotion,

intelligence,

phenomenology,

motivation,

brain functioning,

personality, behavior, and

interpersonal relationships, including

psychological resilience,

family resilience, and other areas. Psychologists of diverse orientations also consider the

unconscious mind.

[5] Psychologists employ

empirical methods to infer

causal and

correlational relationships between psychosocial

variables. In

addition, or in

opposition, to employing

empirical and

deductive methods, some—especially

clinical and

counseling psychologists—at times rely upon

symbolic interpretation and other

inductive techniques. Psychology has been described as a "hub science",

[6] with psychological findings linking to research and perspectives from the social sciences,

natural sciences,

medicine,

humanities, and

philosophy.

While psychological knowledge is often applied to the

assessment and

treatment of

mental health problems, it is also directed towards understanding and solving problems in several spheres of

human activity. By many accounts psychology ultimately aims to benefit society.

[7][8] The majority of psychologists are involved in some kind of therapeutic role, practicing in clinical,

counseling, or

school settings. Many do scientific research on a wide range of topics related to mental processes and behavior, and typically work in university psychology departments or teach in other academic settings (e.g., medical schools, hospitals). Some are employed in

industrial and organizational settings, or in other areas

[9] such as

human development and aging,

sports,

health, and

the media, as well as in

forensic investigation and other aspects of

law.

Etymology

The word

psychology derives from Greek roots meaning study of the

psyche, or

soul (

ψυχή psukhē, "breath, spirit, soul" and -λογία

-logia, "study of" or "research").

[10] The

Latin word

psychologia was first used by the

Croatian humanist and

Latinist Marko Marulić in his book,

Psichiologia de ratione animae humanae in the late 15th century or early 16th century.

[11] The earliest known reference to the word

psychology in English was by

Steven Blankaart in 1694 in

The Physical Dictionary which refers to "Anatomy, which treats the Body, and Psychology, which treats of the Soul."

[12]

History

The ancient civilizations of

Egypt,

Greece,

China,

India, and

Persia all engaged in the

philosophical study of psychology. Historians note that Greek philosophers, including

Thales,

Plato, and

Aristotle (especially in his

De Anima treatise),

[13] addressed the workings of the mind.

[14] As early as the 4th century BC, Greek physician

Hippocrates theorized that

mental disorders had physical rather than supernatural causes.

[15]

In China, psychological understanding grew from the philosophical works of

Laozi and

Confucius, and later from the doctrines of Buddhism. This body of knowledge involves insights drawn from introspection and observation, as well as techniques for focused thinking and acting. It frames the universe as a division of, and interaction between, physical reality and mental reality, with an emphasis on purifying the mind in order to increase virtue and power. An ancient text known as

The Yellow Emperor's Classic of Internal Medicine identifies the brain as the nexus of wisdom and sensation, includes theories of personality based on

yin–yang balance, and analyzes mental disorder in terms of physiological and social disequilibria. Chinese scholarship focused on the brain advanced in the

Qing Dynasty with the work of Western-educated Fang Yizhi (1611–1671), Liu Zhi (1660–1730), and Wang Qingren (1768–1831). Wang Qingren emphasized the importance of the brain as the center of the nervous system, linked mental disorder with brain diseases, investigated the causes of dreams and insomnia, and advanced a theory of

hemispheric lateralization in brain function.

[16]

Distinctions in types of awareness appear in the ancient thought of India, influenced by

Hinduism. A central idea of the

Upanishads is the distinction between a person's transient mundane self and their

eternal unchanging soul. Divergent Hindu doctrines, and

Buddhism, have challenged this hierarchy of selves, but have all emphasized the importance of reaching higher awareness.

Yoga is a range of techniques used in pursuit of this goal. Much of the Sanskrit corpus was suppressed under the

British East India Company followed by the

British Raj in the 1800s. However, Indian doctrines influenced Western thinking via the

Theosophical Society, a New Age group which became popular among Euro-American intellectuals.

[17]

Psychology was a popular topic in

Enlightenment Europe. In Germany,

Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz (1646–1716) applied his principles of calculus to the mind, arguing that mental activity took place on an indivisible continuum—most notably, that among an infinity of human perceptions and desires, the difference between conscious and unconscious awareness is only a matter of degree.

Christian Wolff identified psychology as its own science, writing

Psychologia empirica in 1732 and

Psychologia rationalis in 1734. This notion advanced further under

Immanuel Kant, who established the idea of

anthropology, with psychology as an important subdivision.

However, Kant explicitly and notoriously rejected the idea of experimental psychology, writing that "the empirical doctrine of the soul can also never approach chemistry even as a systematic art of analysis or experimental doctrine, for in the manifold of inner observation can be separated only by mere division in thought, and cannot then be held separate and recombined at will (but still less does another thinking subject suffer himself to be experimented upon to suit our purpose), and even observation by itself already changes and displaces the state of the observed object." Having consulted philosophers

Georg Friedrich Wilhelm Hegel and

Johann Friedrich Herbart, in 1825 the

Prussian state established psychology as a mandatory discipline in its rapidly expanding and highly influential

educational system. However, this discipline did not yet embrace experimentation.

[18] In England, early psychology involved

phrenology and the response to social problems including alcoholism, violence, and the country's well-populated mental asylums.

[19]

Beginning of experimental psychology

Wilhelm Wundt (seated) with colleagues in his psychological laboratory, the first of its kind.

Gustav Fechner began conducting psychology research in

Leipzig in the 1830s, studying

psychophysics and articulating the

principle that human perception of a stimulus varies logarithmically according to its intensity.

[20] Fechner's 1950

Elements of Psychophysics challenged Kant's stricture against quantitative study of the mind.

[18] In Heidelberg,

Hermann von Helmholtz conducted parallel research on sensory perception, and trained physiologist

Wilhelm Wundt. Wundt, in turn, came to Leipzig University, establishing the psychological

laboratory which brought

experimental psychology to the world. Wundt focused on breaking down mental processes into the most basic components, motivated in part by an analogy to recent advances in chemistry, and its successful investigation of the elements and structure of material.

[21] Paul Flechsig and

Emil Kraepelin soon created another influential psychology laboratory at Leipzig, this one focused on more on experimental

psychiatry.

[18]

Psychologists in Germany, Denmark, Austria, England, and the United States soon followed Wundt in setting up laboratories.

[22] G. Stanley Hall who studied with Wundt, formed a psychology lab at

Johns Hopkins University in Maryland, which became internationally influential. Hall, in turn, trained Yujiro Motora, who brought experimental psychology, emphasizing psychophysics, to the

Imperial University of Tokyo.

[23] Wundt assistant

Hugo Münsterberg taught psychology at Harvard to students such as

Narendra Nath Sen Gupta—who, in 1905, founded a psychology department and laboratory at the

University of Calcutta.

[17] Wundt students

Walter Dill Scott,

Lightner Witmer, and

James McKeen Cattell worked on developing tests for mental ability. Catell, who also studied with eugenicist

Francis Galton, went on to found the

Psychological Corporation. Wittmer focused on mental testing of children; Scott, on selection of employees.

[24]

Another student of Wundt,

Edward Titchener, created the psychology program at

Cornell University and advanced a doctrine of

"structuralist" psychology. Structuralism sought to analyze and classify different aspects of the mind, primarily through the method of

introspection.

[25] William James,

John Dewey and

Harvey Carr advanced a more expansive doctrine called

functionalism, attuned more to human–environment actions. In 1890 James wrote an influential book,

The Principles of Psychology, which expanded on the realm of structuralism, memorably described the human "

stream of consciousness", and interested many American students in the emerging discipline.

[26][27][25] Dewey integrated psychology with social issues, most notably by promoting the cause

progressive education to assimilate immigrants and inculcate moral values in children.

[28]

A different strain of experimentalism, with more connection to physiology, emerged in South America, under the leadership of Horacio G. Piñero at the

University of Buenos Aires.

[29] Russia, too, placed greater emphasis on the biological basis for psychology, beginning with

Ivan Sechenov's 1873 essay, "Who Is to Develop Psychology and How?" Sechenov advanced the idea of brain

reflexes and aggressively promoted a deterministic (contra

free will) viewpoint on human behavior.

[30]

Wolfgang Kohler,

Max Wertheimer and

Kurt Koffka co-founded the school of

Gestalt psychology (not to be confused with the

Gestalt therapy of

Fritz Perls). This approach is based upon the idea that individuals experience things as unified wholes. Rather than

breaking down thoughts and behavior into smaller elements, as in structuralism, the Gestaltists maintained that whole of experience is important, and differs from the sum of its parts. Other 19th-century contributors to the field include the German psychologist

Hermann Ebbinghaus, a pioneer in the experimental study of

memory, who developed quantitative models of learning and forgetting at the

University of Berlin,

[31] and the Russian-Soviet

physiologist Ivan Pavlov, who discovered in dogs a learning process that was later termed "

classical conditioning" and applied to human beings.

[32]

Disciplinary consolidation

One of the earliest psychology societies was

La Société de Psychologie Physiologique in France, which lasted 1885–1893. The first meeting of the International Congress of Psychology took place in Paris, in August 1889, amidst

the World's Fair celebrating the centennial of the French Revolution. William James was one of three Americans among the four hundred attendees. The

American Psychological Association was founded soon after, in 1892. The International Congress continued to be held, at different locations in Europe, with wider international participation. The Sixth Congress, Geneva 1909, included presentations in Russian, Chinese, and Japanese, as well as

Esperanto. After a hiatus for

World War I, the Seventh Congress met in Oxford, with substantially greater participation from the war-victorious Anglo-Americans. In 1929, the Congress took place at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut, attended by hundreds of members of the American Psychological Association

[22] Tokyo Imperial University led the way in bringing the new psychology to the East, and from Japan these ideas diffused into China.

[23][16]

Early practitioners of experimental psychology distinguished themselves from

parapsychology, which in the late nineteenth century enjoyed great popularity (including the interest of scholars such as William James), and indeed constituted the bulk of what people called "psychology". Parapsychology,

hypnotism, and

psychism were major topics of the early International Congresses. But students of these fields were eventually ostractized, and more or less banished from the Congress in 1900–1905.

[22] Parapsychology persisted for a time at Imperial University, with publications such as

Clairvoyance and Thoughtography by Tomokichi Fukurai, but here too it was mostly shunned by 1913.

[23]

After the Russian Revolution, psychology was heavily promoted by the

Bolsheviks as a way to engineer the "New Man" of socialism. Thus, university psychology departments trained large numbers of students, for whom positions were made available at schools, workplaces, cultural institutions, and in the military. An especial focus was

pedology, the study of child development, regarding which

Lev Vygotsky became a prominent writer. Although pedology fell out of favor in 1936, psychology maintained its privileged position as an instrument of the Soviet state.

[30] In Germany after World War I, psychology held institutional power through the military, and subsequently expanded along with the rest of the military under the

Third Reich.

[18]

In 1920,

Édouard Claparède and Pierre Bovet created a new

applied psychology organization called the International Congress of Psychotechnics Applied to Vocational Guidance, later called the International Congress of Psychotechnics and then the

International Association of Applied Psychology.

[22] The world federation of national psychological societies is the

International Union of Psychological Science, founded in 1951 under the auspices of

UNESCO, the United Nations cultural and scientific authority.

[33][22] Psychology departments have since proliferated around the world, based primarily on the Euro-American model.

[17][33] Since 1966, the Union has published the

International Journal of Psychology.

[22] Membership in the American Psychological Association increased from 5,000 in 1945 to 100,000 in the present day.

[25]

Behaviorism

An early researcher into psychological

conditioning was

Ivan Pavlov, known best for inducing dogs to salivate in the presence of a stimulus previous linked with food. As the star of psychology rose over the

Soviet Union, Pavlov became a leading figure and attracted many followers, who applied his theories to humans.

[30] In the United States, "

connectionism" studies were conducted by

Edward Lee Thorndike, who trapped animals in "puzzle boxes" and rewarded them for escaping. Like Pavlov, Thorndike focused narrowly on stimulus-response (S–R) pairings. He believed that the field of human psychology should focus on outward behavior, writing in 1911: "There can be no moral warrant for studying man's nature unless the study will enable us to control his acts."

[34] John B. Watson, teaching at Johns Hopkins, led a rising tide of sentiment in the United States against the idea that psychology had to study consciousness itself. From 1910–1913 the American Psychological Association went through a sea change of opinion, away from mentalism and towards "behavioralism", and in 191 Watson coined the term

behaviorism for this school of thought.

[35] Behaviorism, embraced and extended by

Clark L. Hull,

Edward C. Tolman,

Edwin Guthrie and many others, focused on the way organisms respond to environmental

stimuli eliciting

pain or

pleasure.

[25]

Behaviorism became a dominant school of thought in the midcentury United States, with

B.F. Skinner its leading intellectual. Skinner's behaviorism shared with its predecessors a philosophical inclination toward

positivism,

determinism, and the study of observable behavior.

[36][37] In lieu of probing an "unconscious mind" that underlies unawareness, behaviorists spoke of the "contingency-shaped behaviors" in which unawareness becomes outwardly manifest.

[36] Notable incidents in the history of behaviorism are John B. Watson's

Little Albert experiment which applied classical conditioning to the developing human child, and the clarification of the difference between classical conditioning and

operant (or instrumental) conditioning, first by Miller and Kanorski and then by Skinner.

[38][39] Skinner's version of behaviorism emphasized operant conditioning, through which behaviors are strengthened or weakened by their consequences.

Noam Chomsky delivered an influential critique of behaviorism on the grounds that it could not adequately explain the complex mental process of

language acquisition.

[40][41] Martin Seligman and colleagues discovered that the conditioning of dogs led to outcomes ("

learned helplessness") that opposed the predictions of behaviorism.

[42][43] Skinner's behaviorism did not die, perhaps in part because it generated successful practical applications.

[40]

The

Association for Behavior Analysis International was founded in 1974 and by 2003 had members from 42 countries. The field has been especially influential in Latin America, where it has a regional organization known as ALAMOC:

La Asociación Latinoamericana de Análisis y Modificación del Comportamiento. Behaviorism also gained a strong foothold in Japan, where it gave rise to the Japanese Society of Animal Psychology (1933), the Japanese Association of Special Education (1963), the Japanese Society of Biofeedback Research (1973), the Japanese Association for Behavior Therapy (1976), the Japanese Association for Behavior Analysis (1979), and the Japanese Association for Behavioral Science Research (1994).

[44] Today the field of behaviorism is also commonly referred to as

behavior modification or

behavior analysis.

[44]

Psychoanalysis

Beginning in the 1890s, Austrian psychologists including

Josef Breuer Alfred Adler,

Otto Rank, and most prominently

Sigmund Freud, developed an influential school of thought and clinical practice called

psychoanalysis.

Psychoanalysis comprises a method of investigating the mind and interpreting experience; a systematized set of theories about human behavior; and a form of psychotherapy to treat psychological or emotional distress, especially unconscious conflict.

[45] Freud's psychoanalytic theory was largely based on interpretive methods,

introspection and clinical observations. It became very well known, largely because it tackled subjects such as

sexuality,

repression, and the

unconscious mind as general aspects of psychological development. These were largely considered taboo subjects at the time, and Freud provided a catalyst for them to be openly discussed in polite society. Clinically,

Freud helped to pioneer the method of

free association and a therapeutic interest in

dream interpretation.

[46][47]

Freud had a significant influence on Swiss psychiatrist

Carl Jung, whose theories of

analytical psychology include such well-known concepts as the

collective unconscious. Modification of Jung's theories led to the

archetypal and

process-oriented schools. Other well-known psychoanalytic scholars of the mid-20th century include

Erik Erikson,

Melanie Klein,

D.W. Winnicott,

Karen Horney,

Erich Fromm,

John Bowlby, and Sigmund Freud's daughter,

Anna Freud. Throughout the 20th century, psychoanalysis evolved into diverse schools of thought which could be called

Neo-Freudian. Among these schools are

ego psychology,

object relations, and

interpersonal,

Lacanian, and

relational psychoanalysis.

Psychoanalytic theory and therapy were criticized by psychologists such as

Hans Eysenck, and by philosophers including

Karl Popper. Popper, a

philosopher of science, argued that psychoanalysis had been misrepresented as a scientific discipline,

[48] whereas Eysenck said that psychoanalytic tenets had been contradicted by

experimental data. By the end of 20th century, psychology departments in

American universities had become

scientifically oriented, marginalizing Freudian theory and dismissing it as a "desiccated and dead" historical artifact.

[49] Meanwhile, however, researchers in the emerging field of

neuro-psychoanalysis defended some of Freud's ideas on scientific grounds,

[50] while scholars of the

humanities maintained that Freud was not a "scientist at all, but ... an

interpreter."

[49]

Existential-humanistic theories

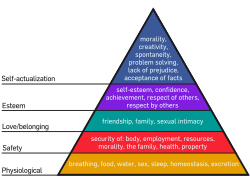

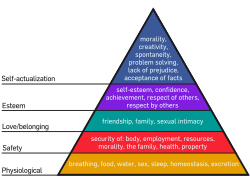

Psychologist Abraham Maslow in 1943 posited that humans have a hierarchy of needs, and it makes sense to fulfill the basic needs first (food, water etc.) before higher-order needs can be met.

[51]

Humanistic psychology was developed in the 1950s in reaction to both behaviorism and psychoanalysis.

[52] By using

phenomenology,

intersubjectivity, and first-person categories, the humanistic approach sought to glimpse the whole person—not just the fragmented parts of the personality or cognitive functioning.

[53] Humanism focused on fundamentally and uniquely human issues, such as individual

free will, personal growth,

self-actualization,

self-identity,

death,

aloneness,

freedom, and

meaning. The humanistic approach was distinguished by its emphasis on subjective meaning, rejection of determinism, and concern for positive growth rather than pathology.

[citation needed] Some founders of the humanistic school of thought were American psychologists

Abraham Maslow, who formulated a

hierarchy of human needs, and

Carl Rogers, who created and developed

client-centered therapy.

Later,

positive psychology opened up humanistic themes to scientific modes of exploration.

In the 1950s and 1960s, largely influenced by the work of German philosopher

Martin Heidegger and Danish philosopher

Søren Kierkegaard, psychoanalytically trained American psychologist

Rollo May pioneered an

existential branch of psychology, which included

existential psychotherapy, a method of therapy that operates on the belief that inner conflict within a person is due to that individual's confrontation with the givens of existence. Swiss psychoanalyst

Ludwig Binswanger and American psychologist

George Kelly may also be said to belong to the existential school.

[54]

Existential psychologists differed from more "humanistic" psychologists in their relatively neutral view of

human nature and their relatively positive assessment of

anxiety.

[55] Existential psychologists emphasized the humanistic themes of death, free will, and meaning, suggesting that meaning can be shaped by

myths, or narrative patterns,

[56] and that it can be encouraged by an acceptance of the free will requisite to an

authentic, albeit often anxious, regard for death and other future prospects.

Austrian existential psychiatrist and

Holocaust survivor

Viktor Frankl drew evidence of meaning's therapeutic power from reflections garnered from his own

internment,

[57] and he created a variation of existential psychotherapy called

logotherapy, a type of

existentialist analysis that focuses on a

will to meaning (in one's life), as opposed to Adler's

Nietzschean doctrine of

will to power or Freud's

will to pleasure.

[58]

Cognitive revolution

Starting in the 1950s, the experimental techniques developed by Wundt, James, Ebbinghaus, and others re-emerged as experimental psychology became increasingly cognitivist—concerned with

information and its

processing—and, eventually, constituted a part of the wider

cognitive science.

[59] In its early years, this development was seen as a

"revolution,"

[59] as cognitive science both responded to and reacted against then-popular theories, including

psychoanalytic and

behaviorist theories.

Noam Chomsky helped to launch a "

cognitive revolution" in psychology when he criticized the behaviorists' notions of "stimulus", "response", and "reinforcement". Chomsky argued that such ideas—which Skinner had borrowed from animal experiments in the laboratory—could be applied to complex human behavior, most notably language acquisition, in only a superficial and vague manner. The postulation that humans are born with the instinct or "

innate facility" for acquiring language posed a challenge to the position that all behavior, including language, is contingent upon learning and reinforcement.

[60] Social learning theorists, such as

Albert Bandura, argued that the child's environment could make contributions of its own to the behaviors of an observant subject.

[61]

The

Müller–Lyer illusion. Psychologists make inferences about mental processes from shared phenomena such as optical illusions.

Meanwhile, technological advances helped to renew interest and belief in the mental states and representations—i.e., cognition—that had fallen out of favor with behaviorists. English neuroscientist

Charles Sherrington and Canadian psychologist

Donald O. Hebb used experimental methods to link psychological phenomena with the structure and function of the brain. With the rise of

computer science and

artificial intelligence, analogies were drawn between the processing of information by humans and information processing by machines. Research in cognition had proven practical since

World War II, when it aided in the understanding of weapons operation.

[62] By the late 20th century cognitivism had become the dominant

paradigm of psychology, and

cognitive psychology emerged as a popular branch.

Assuming both that the covert mind should be studied, and that the scientific method should be used to study it, cognitive psychologists set such concepts as

subliminal processing and

implicit memory in place of the psychoanalytic

unconscious mind or the behavioristic

contingency-shaped behaviors. Elements of behaviorism and cognitive psychology were synthesized to form the basis of

cognitive behavioral therapy, a form of psychotherapy modified from techniques developed by American psychologist

Albert Ellis and American psychiatrist

Aaron T. Beck. Cognitive psychology was subsumed along with other disciplines, such as

philosophy of mind, computer science, and neuroscience, under the cover discipline of cognitive science.

Subfields

Psychology encompasses many subfields and includes different approaches to the study of mental processes and behavior:

Biological

MRI depicting the human brain. The arrow indicates the position of the

hypothalamus.

Biological psychology or

behavioral neuroscience is the study of the biological substrates of behavior and mental processes. There are different specialties within behavioral neuroscience. For example,

physiological psychologists use animal models, typically rats, to study the neural, genetic, and cellular mechanisms that underlie specific behaviors such as learning and memory and fear responses.

[63] Cognitive neuroscientists investigate the neural correlates of psychological processes in humans using neural imaging tools, and

neuropsychologists conduct psychological assessments to determine, for instance, specific aspects and extent of cognitive deficit caused by brain damage or disease.

Clinical

Clinical psychologists work with individuals, children, families, couples, or small groups.

Clinical psychology includes the study and application of psychology for the purpose of understanding, preventing, and relieving psychologically based distress or

dysfunction and to promote subjective

well-being and personal development. Central to its practice are psychological assessment and

psychotherapy, although clinical psychologists may also engage in research, teaching, consultation, forensic testimony, and program development and administration.

[64] Some clinical psychologists may focus on the clinical management of patients with

brain injury—this area is known as

clinical neuropsychology. In many countries, clinical psychology is a regulated

mental health profession.

The work performed by clinical psychologists tends to be influenced by various therapeutic approaches, all of which involve a formal relationship between professional and client (usually an individual, couple, family, or small group). The various therapeutic approaches and practices are associated with different theoretical perspectives and employ different procedures intended to form a therapeutic alliance, explore the nature of psychological problems, and encourage new ways of thinking, feeling, or behaving. Four major theoretical perspectives are

psychodynamic,

cognitive behavioral,

existential–humanistic, and systems or

family therapy. There has been a growing movement to integrate the various therapeutic approaches, especially with an increased understanding of issues regarding culture, gender, spirituality, and sexual orientation. With the advent of more robust research findings regarding psychotherapy, there is evidence that most of the major therapies are about of equal effectiveness, with the key common element being a strong therapeutic alliance.

[65][66] Because of this, more training programs and psychologists are now adopting an

eclectic therapeutic orientation.

[67][68][69][70][71]

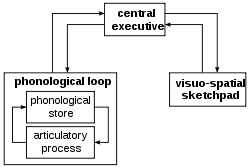

Cognitive

Cognitive psychology studies

cognition, the

mental processes underlying mental activity.

Perception,

attention,

reasoning,

thinking,

problem solving,

memory,

learning,

language, and

emotion are areas of research. Classical cognitive psychology is associated with a school of thought known as

cognitivism, whose adherents argue for an

information processing model of mental function, informed by

functionalism and

experimental psychology.

On a broader level,

cognitive science is an interdisciplinary enterprise of

cognitive psychologists,

cognitive neuroscientists, researchers in

artificial intelligence,

linguists,

human–computer interaction,

computational neuroscience,

logicians and

social scientists.

Computational models are sometimes used to simulate phenomena of interest. Computational models provide a tool for studying the functional organization of the mind whereas neuroscience provides measures of brain activity.

Comparative

The common

chimpanzee can use

tools. This chimpanzee is using a stick in order to get food.

Comparative psychology refers to the scientific study of the behavior and mental processes of non-human animals, especially as these relate to the phylogenetic history, adaptive significance, and development of behavior. Research in this area addresses many issues, uses many methods, and explores the behavior of many species, from insects to primates. It is closely related to other disciplines that study animal behavior such as

ethology.

[72] Research in comparative psychology sometimes appears to shed light on human behavior, but some attempts to connect the two have been quite controversial, for example the

Sociobiology of

E. O. Wilson.

[73] Animal models are often used to study neural processes related to human behavior, e.g. in

cognitive neuroscience.

Developmental

Developmental psychologists would engage a child with a book and then make observations based on how the child interacts with the object.

Mainly focusing on the development of the human mind through the life span,

developmental psychology seeks to understand how people come to perceive, understand, and act within the world and how these processes change as they age. This may focus on cognitive, affective,

moral, social, or neural development. Researchers who study children use a number of unique research methods to make observations in natural settings or to engage them in experimental tasks. Such tasks often resemble specially designed games and activities that are both enjoyable for the child and scientifically useful, and researchers have even devised clever methods to study the mental processes of infants. In addition to studying children, developmental psychologists also study

aging and processes throughout the life span, especially at other times of rapid change (such as

adolescence and

old age). Developmental psychologists draw on the full range of psychological theories to inform their research.

Educational and school

An example of an item from a cognitive abilities test used in educational psychology.

Educational psychology is the study of how humans learn in

educational settings, the effectiveness of educational interventions, the psychology of teaching, and the

social psychology of

schools as organizations. The work of child psychologists such as

Lev Vygotsky,

Jean Piaget,

Bernard Luskin, and

Jerome Bruner has been influential in creating

teaching methods and educational practices. Educational psychology is often included in teacher education programs in places such as North America, Australia, and New Zealand.

School psychology combines principles from

educational psychology and

clinical psychology to understand and treat students with learning disabilities; to foster the intellectual growth of

gifted students; to facilitate

prosocial behaviors in adolescents; and otherwise to promote safe, supportive, and effective learning environments. School psychologists are trained in educational and behavioral assessment, intervention, prevention, and consultation, and many have extensive training in research.

[74]

Evolutionary

Evolutionary psychology examines psychological

traits—such as

memory,

perception, or

language—from a

modern evolutionary perspective. It seeks to identify which human psychological traits are evolved

adaptations, that is, the functional products of

natural selection or

sexual selection. Evolutionary psychologists suggest that

psychological adaptations evolved to solve recurrent problems in human ancestral environments. By focusing on the evolution of psychological traits and their adaptive functions, it offers complementary explanations for the mostly proximate or developmental explanations developed by other areas of psychology (that is, it focuses mostly on ultimate or "why?" questions, rather than proximate or "how?" questions).

Industrial–organizational

Industrial and organizational psychology (I–O) applies psychological concepts and methods to optimize human potential in the workplace. Personnel psychology, a subfield of I–O psychology, applies the methods and principles of psychology in selecting and evaluating workers. I–O psychology's other subfield,

organizational psychology, examines the effects of work environments and management styles on worker motivation,

job satisfaction, and productivity.

[75]

Personality

Personality psychology is concerned with enduring patterns of

behavior,

thought, and

emotion—commonly referred to as

personality—in individuals. Theories of personality vary across different psychological schools and orientations. They carry different assumptions about such issues as the role of the

unconscious and the importance of childhood experience. According to Freud, personality is based on the dynamic interactions of the

id, ego, and super-ego.

[76] Trait theorists, in contrast, attempt to analyze personality in terms of a discrete number of key traits by the statistical method of

factor analysis. The number of proposed traits has varied widely. An early model, proposed by

Hans Eysenck, suggested that there are three traits which comprise human personality:

extraversion–introversion,

neuroticism, and

psychoticism.

Raymond Cattell proposed a theory of

16 personality factors.

Increasingly, web-based surveys are being used in research for its convenience and also to get a wide range of participants. Similar methodology is also used in applied setting, such as clinical assessment and

personnel assessment.

Longitudinal studies

Longitudinal studies are often used in psychology to study developmental trends across the life span, and in

sociology to study life events throughout lifetimes or generations. The reason for this is that unlike

cross-sectional studies, longitudinal studies track the same people, and therefore the differences observed in those people are less likely to be the result of cultural differences across generations. Because of this benefit, longitudinal studies make observing changes more accurate and they are applied in various other fields.

Because most longitudinal studies are observational, in the sense that they observe the state of the world without manipulating it, it has been argued that they may have less power to detect causal relationships than do experiments. They also suffer methodological limitations such as from selective attrition because people with similar characteristics may be more likely to drop out of the study making it difficult to analyze.

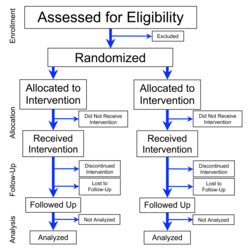

Some longitudinal studies are

experiments, called

repeated-measures experiments. Psychologists often use the

crossover design to reduce the influence of

confounding covariates and to

reduce the number of subjects.

Observation in natural settings

Phineas P. Gage survived an accident in which a large iron rod was driven completely through his head, destroying much of his brain's left frontal lobe, and is remembered for that injury's reported effects on his personality and behavior.

[80]

Just as

Jane Goodall studied

chimpanzee social and family life by careful observation of chimpanzee behavior in the field, psychologists conduct observational studies of ongoing human social, professional, and family life.

Sometimes the participants are aware they are being observed, and other times the participants do not know they are being observed. Strict ethical guidelines must be followed when covert observation is being carried out.

Qualitative and descriptive research

Artificial neural network with two layers, an interconnected group of nodes, akin to the vast network of neurons in the human brain.

Research designed to answer questions about the current state of affairs such as the thoughts, feelings, and behaviors of individuals is known as

descriptive research. Descriptive research can be qualitative or quantitative in orientation.

Qualitative research is descriptive research that is focused on observing and describing events as they occur, with the goal of capturing all the richness of everyday behavior and with the hope of discovering and understanding phenomena that might have been missed if only more cursory examinations have been made.

Neuropsychological methods

Neuropsychological research methods are employed in studies that examine the relation of mental activity and behavior to the structure and function of the

brain. These methods include testing (e.g., the various

Wechsler scales,

Wisconsin Card Sorting Test),

functional neuroimaging, and

transcranial magnetic stimulation.

Computational modeling

The experimenter (E) orders the teacher (T), the subject of the experiment, to give what the latter believes are painful electric shocks to a learner (L), who is actually an actor and

confederate. The subject believes that for each wrong answer, the learner was receiving actual electric shocks, though in reality there were no such punishments. Being separated from the subject, the confederate set up a tape recorder integrated with the electro-shock generator, which played pre-recorded sounds for each shock level etc.

[81]

Computational modeling[82] is a tool often used in

mathematical psychology and

cognitive psychology to simulate a particular behavior using a computer. This method has several advantages. Since modern computers process information extremely quickly, many simulations can be run in a short time, allowing for a great deal of statistical power. Modeling also allows psychologists to visualize hypotheses about the functional organization of mental events that couldn't be directly observed in a human.

Several types of modeling are used to study behavior.

Connectionism uses

neural networks to simulate the brain. Another method is symbolic modeling, which represents many mental objects using variables and rules. Other types of modeling include

dynamic systems and

stochastic modeling.

Animal studies

Animal experiments aid in investigating many aspects of human psychology, including perception, emotion, learning, memory, and thought, to name a few. In the 1890s, Russian physiologist

Ivan Pavlov famously used dogs to demonstrate

classical conditioning.

Non-human primates, cats, dogs, pigeons,

rats, and other

rodents are often used in psychological experiments. Ideally, controlled experiments introduce only one

independent variable at a time, in order to ascertain its unique effects upon dependent variables. These conditions are approximated best in laboratory settings. In contrast, human environments and genetic backgrounds vary so widely, and depend upon so many factors, that it is difficult to control important variables for human subjects. Of course, there are pitfalls in generalizing findings from animal studies to humans through animal models.

[83]

Criticism

Replication crisis

Psychology has recently found itself at the center of a "replication crisis" due to some research findings proving difficult to replicate. Replication failures are not unique to psychology and are found in all fields of science.

However, several factors have combined to put psychology at the center of the current controversy. Much of the focus has been on the area of social psychology, although other areas of psychology such as clinical psychology have also been implicated.

Firstly, questionable researcher practices (QRP) have been identified as common in the field. Such practices, while not intentionally fraudulent, involve converting undesired statistical outcomes into desired outcomes via the manipulation of statistical analyses, sample size or data management, typically to convert non-significant findings into significant ones.

[84] Some studies have suggested that at least mild versions of QRP are highly prevalent.

[85] False positive conclusions, often resulting from the

pressure to publish or the author's own

confirmation bias, are an inherent hazard in the field, requiring a certain degree of

skepticism on the part of readers.

[86]

Secondly, psychology and social psychology in particular, has found itself at the center of several recent scandals involving outright fraudulent research. Most notably the admitted data fabrication by

Diederik Stapel[87] as well as allegations against others. However, most scholars acknowledge that fraud is, perhaps, the lesser contribution to replication crises.

Third, several effects in psychological science have been found to be difficult to replicate even before the current replication crisis. For example the scientific journal

Judgment and Decision Making has published several studies over the years that fail to provide support for the

unconscious thought theory. Replications appear particularly difficult when research trials are pre-registered and conducted by research groups not highly invested in the theory under questioning.

These three elements together have resulted in renewed attention for replication supported by

Kahneman. Scrutiny of many effects have shown that several core beliefs are hard to replicate. A recent special edition of the journal Social Psychology focused on replication studies and a number of previously held beliefs were found to be difficult to replicate.

[88] A 2012 special edition of the journal Perspectives on Psychological Science also focused on issues ranging from publication bias to null-aversion that contribute to the replication crises in psychology

[89]

Scholar James Coyne has recently written that many research trials and meta-analyses are compromised by poor quality and conflicts of interest that involve both authors and professional advocacy organizations, resulting in many false positives regarding the effectiveness of certain types of psychotherapy.

[90]

It is important to note that this replication crisis does not mean that psychology is unscientific. Rather, this process is a healthy if sometimes acrimonious part of the scientific process in which old ideas or those that cannot withstand careful scrutiny are pruned.

[91] The consequence is that some areas of psychology once considered solid, such as

social priming, have come under increased scrutiny due to failed replications.

[92]

Theory

Criticisms of psychological research often come from perceptions that it is a "soft" science. Philosopher of science

Thomas Kuhn's 1962 critique

[93] implied psychology overall was in a pre-paradigm state, lacking the agreement on overarching theory found in mature sciences such as

chemistry and

physics.

Because some areas of psychology rely on research methods such as surveys and

questionnaires, critics have asserted that psychology is not an objective science. Other concepts that psychologists are interested in, such as

personality,

thinking, and

emotion, cannot be directly measured

[94] and are often inferred from subjective self-reports, which may be problematic.

[95][96]

Some critics view

statistical hypothesis testing as misplaced. Research

[which?] has documented that many psychologists confuse

statistical significance with

practical importance. Statistically significant but practically unimportant results are common with large samples.

[97] Some psychologists have responded with an increased use of

effect size statistics, rather than sole reliance on the

Fisherian p < .05 significance criterion (whereby an observed difference is deemed "

statistically significant" if an effect of that size or larger would occur with 5% -or less-

probability in

independent replications, assuming the truth of the

null-hypothesis of no difference between the treatments).

[citation needed]

Sometimes the debate comes from within psychology, for example between laboratory-oriented researchers and practitioners such as clinicians. In recent years, and particularly in the U.S., there has been increasing

debate about the nature of therapeutic effectiveness and about the relevance of empirically examining psychotherapeutic strategies.

[98]

Practice

Psychology Wiki snap shot

Some observers perceive a gap between scientific theory and its application—in particular, the application of unsupported or unsound clinical practices.

[99] Critics say there has been an increase in the number of mental health training programs that do not instill scientific competence.

[100] One skeptic asserts that practices, such as "

facilitated communication for infantile autism"; memory-recovery techniques including

body work; and other therapies, such as

rebirthing and

reparenting, may be dubious or even dangerous, despite their popularity.

[101] In 1984, Allen Neuringer made a similar point

[vague] regarding the experimental analysis of behavior.

[102]

Ethical standards

Current ethical standards of psychology would not permit some studies to be conducted today. These human studies would violate the

Ethics Code of the American Psychological Association, the Canadian Code of Conduct for Research Involving Humans, and the

Belmont Report. Current ethical guidelines state that using non-human animals for scientific purposes is only acceptable when the harm (physical or psychological) done to animals is outweighed by the benefits of the research.

[103] Keeping this in mind, psychologists can use certain research techniques on animals that could not be used on humans.

- An experiment by Stanley Milgram raised questions about the ethics of scientific experimentation because of the extreme emotional stress suffered by the participants. It measured the willingness of study participants to obey an authority figure who instructed them to perform acts that conflicted with their personal conscience.[104]

- Harry Harlow drew condemnation for his "pit of despair" experiments on rhesus macaque monkeys at the University of Wisconsin–Madison in the 1970s.[105] The aim of the research was to produce an animal model of clinical depression. Harlow also devised what he called a "rape rack", to which the female isolates were tied in normal monkey mating posture.[106] In 1974, American literary critic Wayne C. Booth wrote that, "Harry Harlow and his colleagues go on torturing their nonhuman primates decade after decade, invariably proving what we all knew in advance—that social creatures can be destroyed by destroying their social ties." He writes that Harlow made no mention of the criticism of the morality of his work.[107]

University psychology departments have ethics committees dedicated to the rights and well-being of research subjects. Researchers in psychology must gain approval of their research projects before conducting any experiment to protect the interests of human participants and laboratory animals.

[108]

Systemic bias

In 1959 statistician Theodore Sterling examined the results of psychological studies and discovered that 97% of them supported their initial hypotheses, implying a possible

publication bias.

[109][110][111] Similarly, Fanelli (2010)

[112] found that 91.5% of psychiatry/psychology studies confirmed the effects they were looking for, and concluded that the odds of this happening (a positive result) was around five times higher than in fields such as

space- or

geosciences. Fanelli argues that this is because researchers in "softer" sciences have fewer constraints to their conscious and unconscious biases.

In 2010, a group of researchers reported a systemic bias in psychology studies towards WEIRD ("western, educated, industrialized, rich and democratic") subjects.

[113] Although only 1/8 people worldwide fall into the WEIRD classification, the researchers claimed that 60–90% of psychology studies are performed on WEIRD subjects. The article gave examples of results that differ significantly between WEIRD subjects and tribal cultures, including the

Müller-Lyer illusion.