From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

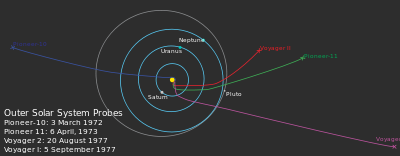

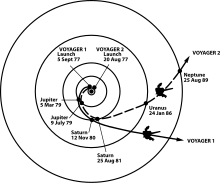

The Voyager program is a continuing American scientific program that employs two robotic probes, Voyager 1 and Voyager 2, to study the outer solar system. They were launched in 1977 to take advantage of a favorable alignment of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune, and are now exploring the outer boundary of the heliosphere. Although their original mission was to study only the planetary systems of Jupiter and Saturn, Voyager 2 continued on to Uranus and Neptune, and both Voyagers are now tasked with exploring interstellar space. Their mission has been extended three times, and both probes continue to collect and relay useful scientific data.

On August 25, 2012, data from Voyager 1 indicated that it had become the first human-made object to enter interstellar space, traveling "further than anyone, or anything, in history".[1] As of 2013[update], Voyager 1 was moving with a velocity of 17 kilometres per second (11 mi/s) relative to the Sun.[2] Voyager 2 is expected to enter interstellar space within a few years of 2016, and its plasma spectrometer should provide the first direct measurements of the density and temperature of the interstellar plasma.[3]

Data and photographs collected by the Voyagers’ cameras, magnetometers, and other instruments revealed previously unknown details about each of the giant planets and their moons. Close-up images from the spacecraft charted Jupiter’s complex cloud forms, winds, and storm systems and discovered volcanic activity on its moon Io. Saturn’s rings were found to have enigmatic braids, kinks, and spokes and to be accompanied by myriad of “ringlets.” At Uranus Voyager 2 discovered a substantial magnetic field around the planet and 10 additional moons. Its flyby of Neptune uncovered three complete rings and six hitherto unknown moons as well as a planetary magnetic field and complex, widely distributed auroras. Voyager 2 is still the only spacecraft to have visited the ice giants.

The Voyager spacecraft were built at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California, and they were paid for by the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), which also paid for their launchings from Cape Canaveral, Florida, their tracking, and everything else concerning the space probes.

History

The two Voyager space probes were originally conceived as part of the Mariner program, and they were thus named Mariner 11 and Mariner 12. They were then moved into a separate program named Mariner Jupiter-Saturn, later renamed the Voyager Program because it was thought that the design of the two space probes had progressed sufficiently beyond that of the Mariner family that they merited a separate name.[4]

The Voyager Program was similar to the Planetary Grand Tour planned during the late 1960s and early 70s. The Grand Tour would take advantage of an alignment of the outer planets discovered by Gary Flandro, an aerospace engineer at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory. This alignment, which occurs once every 175 years,[5] would occur in the late 1970s and make it possible to use gravitational assists to explore Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune, and Pluto. The Planetary Grand Tour was to send several pairs of probes to fly by all the outer planets (and Pluto) along various trajectories, including Jupiter-Saturn-Pluto and Jupiter-Uranus-Neptune. Limited funding ended the Grand Tour program, but elements were incorporated into the Voyager Program, which fulfilled many of the flyby objectives of the Grand Tour except a visit to Pluto.

Voyager 2 was the first to launch. Its trajectory was designed to allow flybys of Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, and Neptune.

Voyager 1 was launched after Voyager 2, but along a shorter and faster trajectory that sent it to Jupiter and Saturn sooner. At Saturn, Voyager 1 could either continue on to Pluto, or make a close flyby of the moon Titan, which was known to be quite large and to possess a dense atmosphere.[6] Since Titan was a high priority target, Voyager 1 was directed there. This encounter sent Voyager 1 out of the plane of the ecliptic, ending its planetary science mission.[7]

During the 1990s, Voyager 1 overtook the slower deep-space probes Pioneer 10 and Pioneer 11 to become the most distant human made object from Earth, a record that it will keep for the foreseeable future. Even the New Horizons probe, which had a higher velocity than Voyager 1 at launch, is traveling slower than Voyager 1 due to the extra speed Voyager 1 gained from its flybys of Jupiter and Saturn. Voyager 1 and Pioneer 10 are the most widely separated human made objects anywhere, since they are traveling in roughly opposite directions from the Solar System.

In December 2004, Voyager 1 crossed the termination shock, where the solar wind is slowed to subsonic speed, and entered the heliosheath, where the solar wind is compressed and made turbulent due to interactions with the interstellar medium. On December 10, 2007, Voyager 2 also reached the termination shock, about 1 billion miles closer to the sun than from where Voyager 1 first crossed it, indicating that the Solar System is asymmetrical.[8]

In 2010 Voyager 1 reported that the outward velocity of the solar wind had dropped to zero, and scientists predicted it was nearing interstellar space.[9] In 2011, data from the Voyagers determined that the heliosheath is not smooth, but filled with giant magnetic bubbles, theorized to form when the magnetic field of the Sun becomes warped at the edge of our Solar System.[10]

On 15 June 2012, scientists at NASA reported that Voyager 1 was very close to entering interstellar space, indicated by a sharp rise in high-energy particles from outside the Solar System.[11][12] In September 2013, NASA announced that Voyager 1 had crossed the heliopause on August 25, 2012, making it the first spacecraft to enter interstellar space.[13][14][15]

As of 2015[update] Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 continue to monitor conditions in the outer expanses of the Solar System. The Voyager spacecraft are expected to be able to operate science instruments through 2020, when limited power will require instruments to be deactivated one by one. Sometime around 2025, there will no longer be sufficient power to operate any science instruments.[16]

Spacecraft design

The Voyager spacecraft weighs 773 kilograms. Of this, 105 kilograms are scientific instruments.[17] The identical Voyager spacecraft use three-axis-stabilized guidance systems that use gyroscopic and accelerometer inputs to their attitude control computers to point their high-gain antennas towards the Earth and their scientific instruments pointed towards their targets, sometimes with the help of a movable instrument platform for the smaller instruments and the electronic photography system.

The diagram at the right shows the high-gain antenna (HGA) with a 3.7 m diameter dish attached to the hollow decagonal electronics container. There is also a spherical tank that contains the hydrazine monopropellant fuel.

The Voyager Golden Record is attached to one of the bus sides. The angled square panel to the right is the optical calibration target and excess heat radiator. The three radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs) are mounted end-to-end on the lower boom.

The scan platform comprises: the Infrared Interferometer Spectrometer (IRIS) (largest camera at top right); the Ultraviolet Spectrometer (UVS) just above the UVS; the two Imaging Science Subsystem (ISS) vidicon cameras to the left of the UVS; and the Photopolarimeter System (PPS) under the ISS.

Only five investigation teams are still supported, though data is collected for two additional instruments.[18] The Flight Data Subsystem (FDS) and a single eight-track digital tape recorder (DTR) provide the data handling functions.

The FDS configures each instrument and controls instrument operations. It also collects engineering and science data and formats the data for transmission. The DTR is used to record high-rate Plasma Wave Subsystem (PWS) data. The data is played back every six months.

The Imaging Science Subsystem, made up of a wide angle and a narrow angle camera, is a modified version of the slow scan vidicon camera designs that were used in the earlier Mariner flights. The Imaging Science Subsystem consists of two television-type cameras, each with eight filters in a commandable Filter Wheel mounted in front of the vidicons. One has a low resolution 200 mm focal length wide-angle lens with an aperture of f/3 (the wide angle camera), while the other uses a higher resolution 1500 mm narrow-angle f/8.5 lens (the narrow angle camera).

Scientific instruments

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Computers

Unlike the other onboard instruments, the operation of the cameras for visible light is not autonomous, but rather it is controlled by an imaging parameter table contained in one of the on-board digital computers, the Flight Data Subsystem (FDS). More recent space probes, since about 1990, usually have completely autonomous cameras.The computer command subsystem (CCS) controls the cameras. The CCS contains fixed computer programs such as command decoding, fault detection, and correction routines, antenna pointing routines, and spacecraft sequencing routines. This computer is an improved version of the one that was used in the Viking orbiter.[21] The hardware in both custom-built CCS subsystems in the Voyagers is identical. There is only a minor software modification for one of them that has a scientific subsystem that the other lacks.

The Attitude and Articulation Control Subsystem (AACS) controls the spacecraft orientation (its attitude). It keeps the high-gain antenna pointing towards the Earth, controls attitude changes, and points the scan platform. The custom-built AACS systems on both craft are identical.

It has been erroneously reported[citation needed] on the Internet that the Voyager space probes were controlled by a version of the RCA 1802 (RCA CDP1802 "COSMAC" microprocessor), but such claims are not supported by the primary design documents. The CDP1802 microprocessor was used later in the Galileo space probe, which was designed and built years later. The digital control electronics of the Voyagers were based on RCA CD4000 radiation-hardened, silicon-on-sapphire (SOS) custom-made integrated circuit chips, combined with standard transistor-transistor logic (TTL) integrated circuits.

Communications

The uplink communications are executed via S-band microwave communications. The downlink communications are carried out by an X-band microwave transmitter on board the spacecraft, with an S-band transmitter as a back-up. All long-range communications to and from the two Voyagers have been carried out using their 3.7-meter high-gain antennas.Because of the inverse-square law in radio communications, the digital data rates used in the downlinks from the Voyagers have been continually decreasing the farther that they get from the Earth. For example, the data rate used from Jupiter was about 115,000 bits per second. That was halved at the distance of Saturn, and it has gone down continually since then. Some measures were taken on the ground along the way to reduce the effects of the inverse-square law. In between 1982 and 1985, the diameters of the three main parabolic dish antennas of the Deep Space Network was increased from 64 m to 70 m, dramatically increasing their areas for gathering weak microwave signals.

Then between 1986 and 1989, new techniques were brought into play to combine the signals from multiple antennas on the ground into one, more powerful signal, in a kind of an antenna array. This was done at Goldstone, California, Canberra, and Madrid using the additional dish antennas available there. Also, in Australia, the Parkes Radio Telescope was brought into the array in time for the fly-by of Neptune in 1989. In the United States, the Very Large Array in New Mexico was brought into temporary use along with the antennas of the Deep Space Network at Goldstone. Using this new technology of antenna arrays helped to compensate for the immense radio distance from Neptune to the Earth.

Power

Electrical power is supplied by three MHW-RTG radioisotope thermoelectric generators (RTGs). They are powered by plutonium-238 (distinct from the Pu-239 isotope used in nuclear weapons) and provided approximately 470 W at 30 volts DC when the spacecraft was launched. Plutonium-238 decays with a half-life of 87.74 years,[22] so RTGs using Pu-238 will lose a factor of 1−0.5(1/87.74) = 0.79% of their power output per year.

In 2011, 34 years after launch, such an RTG would inherently produce 470 W × 2−(34/87.74) ≈ 359 W, about 76% of its initial power. Additionally, the thermocouples that convert heat into electricity also degrade, reducing available power below this calculated level.

By 7 October 2011 the power generated by Voyager 1 and Voyager 2 had dropped to 267.9 W and 269.2 W respectively, about 57% of the power at launch. The level of power output was better than pre-launch predictions based on a conservative thermocouple degradation model. As the electrical power decreases, spacecraft loads must be turned off, eliminating some capabilities.

Voyager Interstellar Mission

The Voyager primary mission was completed in 1989, with the close flyby of Neptune by Voyager 2. The Voyager Interstellar Mission (VIM) is a mission extension, which began when the two spacecraft had already been in flight for over 12 years.[23] The Heliophysics Division of the NASA Science Mission Directorate conducted a Heliophysics Senior Review in 2008. The panel found that the VIM "is a mission that is absolutely imperative to continue" and that VIM "funding near the optimal level and increased DSN (Deep Space Network) support is warranted."[24]As of the present date, the Voyager 2 and Voyager 1 scan platforms, including all of the platform instruments, have been powered down. The ultraviolet spectrometer (UVS)[25] on Voyager 1 was active until 2003, when it too was deactivated. Gyro operations will end in 2015 for Voyager 2 and 2016 for Voyager 1. Gyro operations are used to rotate the probe 360 degrees six times per year to measure the magnetic field of the spacecraft, which is then subtracted from the magnetometer science data.

This diagram about the heliosphere was released on June 28, 2013 and incorporates results from the Voyager spacecraft.[26]

The two Voyager spacecraft continue to operate, with some loss in subsystem redundancy, but retain the capability of returning scientific data from a full complement of Voyager Interstellar Mission (VIM) science instruments.

Both spacecraft also have adequate electrical power and attitude control propellant to continue operating until around 2025, after which there may not be available electrical power to support science instrument operation. At that time, science data return and spacecraft operations will cease.[27]

Telemetry

The telemetry comes to the telemetry modulation unit (TMU) separately as a "low-rate" 40-bit-per-second (bit/s) channel and a "high-rate" channel.Low rate telemetry is routed through the TMU such that it can only be downlinked as uncoded bits (in other words there is no error correction). At high rate, one of a set of rates between 10 bit/s and 115.2 kbit/s is downlinked as coded symbols.

The TMU encodes the high rate data stream with a convolutional code having constraint length of 7 with a symbol rate equal to twice the bit rate (k=7, r=1/2)

Voyager telemetry operates at these transmission rates:

- 7200, 1400 bit/s tape recorder playbacks

- 600 bit/s real-time fields, particles, and waves; full UVS; engineering

- 160 bit/s real-time fields, particles, and waves; UVS subset; engineering

- 40 bit/s real-time engineering data, no science data.

The Voyager crafts have three different telemetry formats:

High rate

- CR-5T (ISA 35395) Science [1], note that this can contain some engineering data.

- FD-12 higher accuracy (and time resolution) Engineering data, note that some science data may also be encoded.

- EL-40 Engineering [2], note that this format can contain some science data, but not all systems represented.

- This is an abbreviated format, with data truncation for some subsystems.

Memory dumps are available in both engineering formats. These routine diagnostic procedures have detected and corrected intermittent memory bit flip problems, as well as detecting the permanent bit flip problem that caused a two-week data loss event mid-2010.

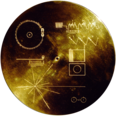

Voyager Golden Record

Voyager 1 and 2 both carry with them a 12 inch golden phonograph record that contains pictures and sounds of Earth along with symbolic directions on the cover for playing the record and data detailing the location of our planet.[12] The record is intended as a combination of a time capsule and an interstellar message to any civilization, alien or far-future human that may recover either of the Voyager craft. The contents of this record were selected by a committee that included Timothy Ferris[12] and was chaired by Carl Sagan.Pale blue dot

Seen from 6 billion kilometers (3.7 billion miles), Earth appears as a "pale blue dot" (the blueish-white speck approximately halfway down the brown band to the right).

"Consider again that dot. That's here. That's home. That's us. On it everyone you love, everyone you know, everyone you ever heard of, every human being who ever was, lived out their lives. The aggregate of our joy and suffering, thousands of confident religions, ideologies, and economic doctrines, every hunter and forager, every hero and coward, every creator and destroyer of civilization, every king and peasant, every young couple in love, every mother and father, hopeful child, inventor and explorer, every teacher of morals, every corrupt politician, every "superstar," every "supreme leader," every saint and sinner in the history of our species lived there – on a mote of dust suspended in a sunbeam".