From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Nuclear binding energy is the energy required to split the nucleus of an atom into its component parts. The component parts are neutrons and protons, which are collectively called nucleons. The binding energy of nuclei is usually a positive number, since most nuclei require net energy to separate them into individual protons and neutrons. Thus, the mass of an atom's nucleus is usually less than the sum of the individual masses of the constituent protons and neutrons when separated. This notable difference is a measure of the nuclear binding energy, which is a result of forces that hold the nucleus together. During the splitting of the nucleus, some of the mass of the nucleus (i.e. some nucleons) gets converted into huge amounts of energy (according to Einstein's equation E=mc2) and thus this mass is removed from the total mass of the original particles, and the mass is missing in the resulting nucleus. This missing mass is known as the mass defect, and represents the energy released when the nucleus is formed.

The term nuclear binding energy may also refer to the energy balance in processes in which the nucleus splits into fragments composed of more than one nucleon, and in this case the binding energies for the fragments, as compared to the whole, will be higher. If new binding energy is available when light nuclei fuse, or when heavy nuclei split, either of these processes result in releases of the binding energy. This energy, available as nuclear energy, can be used to produce electricity (nuclear power) or as a nuclear weapon. When a large nucleus splits into pieces, excess energy is emitted as photons (gamma rays) and as kinetic energy of a number of different ejected particles (nuclear fission products).

The nuclear binding energies and forces are on the order of a million times greater than the electron binding energies of light atoms like hydrogen.[1]

The mass defect of a nucleus represents the mass of the energy of binding of the nucleus, and is the difference between the mass of a nucleus and the sum of the masses of the nucleons of which it is composed. Determining the relevant nuclear binding energy encompasses three steps of calculation, which involves the creation of mass defect by removing the mass as released energy.[2]

Nuclear binding energy is explained by the basic principles involved in nuclear physics.

The best-known classes of exothermic nuclear transmutations are fission and fusion. Nuclear energy may be liberated by atomic fission, when heavy atomic nuclei (like uranium and plutonium) are broken apart into lighter nuclei. The energy from fission is used to generate electric power in hundreds of locations worldwide. Nuclear energy is also released during atomic fusion, when light nuclei like hydrogen are combined to form heavier nuclei such as helium. The Sun and other stars use nuclear fusion to generate thermal energy which is later radiated from the surface, a type of stellar nucleosynthesis. In any exothermic nuclear process, nuclear mass might ultimately be converted to thermal energy, given off as heat, carries away the mass with it.

In order to quantify the energy released or absorbed in any nuclear transmutation, one must know the nuclear binding energies of the nuclear components involved in the transmutation.

The force of electric attraction does not hold nuclei together, because all protons carry a positive charge and repel each other. Thus, electric forces do not hold nuclei together, because they act in the opposite direction. It has been established that binding neutrons to nuclei clearly requires a non-electrical attraction.[4]

Therefore, another force, called the nuclear force (or residual strong force) holds the nucleons of nuclei together. This force is a residuum of the strong interaction, which binds quarks into nucleons at an even smaller level of distance.

The nuclear force must be stronger than the electric repulsion at short distances, but weaker far away, or else different nuclei might tend to clump together. Therefore it has short-range characteristics. An analogy to the nuclear force is the force between two small magnets: magnets are very difficult to separate when stuck together, but once pulled a short distance apart, the force between them drops almost to zero.[4]

Unlike gravity or electrical forces, the nuclear force is effective only at very short distances. At greater distances, the electrostatic force dominates: the protons repel each other because they are positively charged, and like charges repel. For that reason, the protons forming the nuclei of ordinary hydrogen—for instance, in a balloon filled with hydrogen—do not combine to form helium (a process that also would require some to combine with electrons and become neutrons). They cannot get close enough for the nuclear force, which attracts them to each other, to become important. Only under conditions of extreme pressure and temperature (for example, within the core of a star), can such a process take place.[5]

If a combination of particles contains extra energy—for instance, in a molecule of the explosive TNT—weighing it reveals some extra mass, compared to its end products after an explosion. (The weighing must be done after the products have been stopped and cooled, however, as the extra mass must escape from the system as heat before its loss can be noticed, in theory.) On the other hand, if one must inject energy to separate a system of particles into its components, then the initial weight is less than that of the components after they are separated. In the latter case, the energy injected is "stored" as potential energy, which shows as the increased mass of the components that store it. This is an example of the fact that energy of all types is seen in systems as mass, since mass and energy are equivalent, and each is a "property" of the other.

The latter scenario is the case with nuclei such as helium: to break them up into protons and neutrons, one must inject energy. On the other hand, if a process existed going in the opposite direction, by which hydrogen atoms could be combined to form helium, then energy would be released. The energy can be computed using E = Δm c2 for each nucleus, where Δm is the difference between the mass of the helium nucleus and the mass of four protons (plus two electrons, absorbed to create the neutrons of helium).

For elements heavier than oxygen, the energy that can be released by assembling them from lighter elements decreases, up to iron. For nuclei heavier than iron, one actually releases energy by breaking them up into 2 fragments. That is how energy is extracted by breaking up uranium nuclei in nuclear power reactors.

The reason the trend reverses after iron is the growing positive charge of the nuclei. The electric force may be weaker than the nuclear force, but its range is greater: in an iron nucleus, each proton repels the other 25 protons, while the nuclear force only binds close neighbors.

As nuclei grow bigger still, this disruptive effect becomes steadily more significant. By the time polonium is reached (84 protons), nuclei can no longer accommodate their large positive charge, but emit their excess protons quite rapidly in the process of alpha radioactivity—the emission of helium nuclei, each containing two protons and two neutrons. (Helium nuclei are an especially stable combination.) Because of this process, nuclei with more than 98 protons are not found naturally on Earth. The isotopes beyond uranium (atomic number 92) with the longest half-lives are plutonium-244 (80 million years) and curium-247 (16 million years).

Thermal energy appears as the motion of atoms and molecules: the higher the temperature of a collection of particles, the greater is their velocity and the more violent are their collisions. When the temperature at the center of the newly formed Sun became great enough for collisions between nuclei to overcome their electric repulsion, and bring them into the short range of the attractive nuclear force, nuclei began to stick together. When this began to happen, protons combined into deuterium and then helium, with some protons changing in the process to neutrons (plus positrons, positive electrons, which combine with electrons and are destroyed). This released nuclear energy now keeps up the high temperature of the Sun's core, and the heat also keeps the gas pressure high, keeping the Sun at its present size, and stopping gravity from compressing it any more. There is now a stable balance between gravity and pressure.

Different nuclear reactions may predominate at different stages of the Sun's existence, including the proton-proton reaction and the carbon-nitrogen cycle—which involves heavier nuclei, but whose final product is still the combination of protons to form helium.

A branch of physics, the study of controlled nuclear fusion, has tried since the 1950s to derive useful power from nuclear fusion reactions that combine small nuclei into bigger ones, typically to heat boilers, whose steam could turn turbines and produce electricity. Unfortunately, no earthly laboratory can match one feature of the solar powerhouse: the great mass of the Sun, whose weight keeps the hot plasma compressed and confines the nuclear furnace to the Sun's core. Instead, physicists use strong magnetic fields to confine the plasma, and for fuel they use heavy forms of hydrogen, which burn more easily. Magnetic traps can be rather unstable, and any plasma hot enough and dense enough to undergo nuclear fusion tends to slip out of them after a short time. Even with ingenious tricks, the confinement in most cases lasts only a small fraction of a second.

For elements that weigh more than iron (a nucleus with 26 protons), the fusion process no longer releases energy. In even heavier nuclei energy is consumed, not released, by combining similar sized nuclei. With such large nuclei, overcoming the electric repulsion (which affects all protons in the nucleus) requires more energy than what is released by the nuclear attraction (which is effective mainly between close neighbors). Conversely, energy could actually be released by breaking apart nuclei heavier than iron.[5]

With the nuclei of elements heavier than lead, the electric repulsion is so strong that some of them spontaneously eject positive fragments, usually nuclei of helium that form very stable combinations (alpha particles). This spontaneous break-up is one of the forms of radioactivity behavior exhibited by some nuclei.[5]

Nuclei heavier than lead (except for bismuth, thorium, uranium, and plutonium) spontaneously break up too quickly to appear in nature as primordial elements, though they can be produced artificially or as intermediates in the decay chains of lighter elements. Generally, the heavier the nuclei are, the faster they spontaneously decay.[5]

Iron nuclei are the most stable nuclei (in particular iron-56), and the best sources of energy are therefore nuclei whose weights are as far removed from iron as possible. One can combine the lightest ones—nuclei of hydrogen (protons)—to form nuclei of helium, and that is how the Sun generates its energy. Or else one can break up the heaviest ones—nuclei of uranium or plutonium—into smaller fragments, and that is what nuclear power reactors do.[5]

The energy of the nucleus is negative with regard to the energy of the particles pulled apart to infinite distance (just like the gravitational energy of planets of the solar system), because energy must be utilized to split a nucleus into its individual protons and neutrons. Mass spectrometers have measured the masses of nuclei, which are always less than the sum of the masses of protons and neutrons that form them, and the difference—by the formula E = m c2—gives the binding energy of the nucleus.[6]

The conversion of protons to neutrons is the result of another nuclear force, known as the weak (nuclear) force. The weak force, like the strong force, has a short range, but is much weaker than the strong force. The weak force tries to make the number of neutrons and protons into the most energetically stable configuration. For nuclei containing less than 40 particles, these numbers are usually about equal. Protons and neutrons are closely related and are sometimes collectively known as nucleons. As the number of particles increases toward a maximum of about 209, the number of neutrons to maintain stability begins to outstrip the number of protons, until the ratio of neutrons to protons is about three to two.[6]

The protons of hydrogen combine to helium only if they have enough velocity to overcome each other's mutual repulsion sufficiently to get within range of the strong nuclear attraction. This means that fusion only occurs within a very hot gas. Hydrogen hot enough for combining to helium requires an enormous pressure to keep it confined, but suitable conditions exist in the central regions of the Sun, where such pressure is provided by the enormous weight of the layers above the core, pressed inwards by the Sun's strong gravity. The process of combining protons to form helium is an example of nuclear fusion.[6]

The earth's oceans contain a large amount of hydrogen that could theoretically be used for fusion, and helium byproduct of fusion does not harm the environment, so some consider nuclear fusion a good alternative to supply humanity's energy needs. Experiments to generate electricity from fusion have so far have only partially succeeded. Sufficiently hot hydrogen must be ionized and confined. One technique is to use very strong magnetic fields, because charged particles (like those trapped in the Earth's radiation belt) are guided by magnetic field lines. Fusion experiments also rely on heavy hydrogen, which fuses more easily, and gas densities can be moderate. But even with these techniques far more net energy is consumed by the fusion experiments than is yielded by the process.[6]

The net binding energy of a nucleus is that of the nuclear attraction, minus the disruptive energy of the electric force. As nuclei get heavier than helium, their net binding energy per nucleon (deduced from the difference in mass between the nucleus and the sum of masses of component nucleons) grows more and more slowly, reaching its peak at iron. As nucleons are added, the total nuclear binding energy always increases—but the total disruptive energy of electric forces (positive protons repelling other protons) also increases, and past iron, the second increase outweighs the first. Iron-56 (56Fe) is the most efficiently bound nucleus[6] meaning that it has the least average mass per nucleon. However, nickel-62 is the most tightly bound nucleus in terms of energy of binding per nucleon. (Nickel-62's higher energy of binding does not translate to a larger mean mass loss than Fe-56, because Ni-62 has a slightly higher ratio of neutrons/protons than does iron-56, and the presence of the heavier neutrons increases nickel-62's average mass per nucleon).

To reduce the disruptive energy, the weak interaction allows the number of neutrons to exceed that of protons—for instance, the main isotope of iron has 26 protons and 30 neutrons. Isotopes also exist where the number of neutrons differs from the most stable number for that number of nucleons. If the ratio of protons to neutrons is too far from stability, nucleons may spontaneously change from proton to neutron, or neutron to proton.

The two methods for this conversion are mediated by the weak force, and involve types of beta decay. In the simplest beta decay, neutrons are converted to protons by emitting a negative electron and an antineutrino. This is always possible outside a nucleus because neutrons are more massive than protons by an equivalent of about 2.5 electrons. In the opposite process, which only happens within a nucleus, and not to free particles, a proton may become a neutron by ejecting a positron. This is permitted if enough energy is available between parent and daughter nuclides to do this (the required energy difference is equal to 1.022 MeV, which is the mass of 2 electrons). If the mass difference between parent and daughter is less than this, a proton-rich nucleus may still convert protons to neutrons by the process of electron capture, in which a proton simply captures one of the atom's K orbital electrons, emits a neutrino, and becomes a neutron.[6]

Among the heaviest nuclei, starting with tellurium nuclei (element 52) containing 106 or more nucleons, electric forces may be so destabilizing that entire chunks of the nucleus may be ejected, usually as alpha particles, which consist of two protons and two neutrons (alpha particles are fast helium nuclei). (Beryllium-8 also decays, very quickly, into two alpha particles.) Alpha particles are extremely stable. This type of decay becomes more and more probable as elements rise in atomic weight past 106.

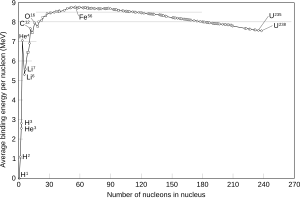

The curve of binding energy is a graph that plots the binding energy per nucleon against atomic mass. This curve has its main peak at iron and nickel and then slowly decreases again, and also a narrow isolated peak at helium, which as noted is very stable. The heaviest nuclei in nature, uranium 238U, are unstable, but having a lifetime of 4.5 billion years, close to the age of the Earth, they are still relatively abundant; they (and other nuclei heavier than iron) may have formed in a supernova explosion [7] preceding the formation of the solar system. The most common isotope of thorium, 232Th, also undergoes α particle emission, and its half-life (time over which half a number of atoms decays) is even longer, by several times. In each of these, radioactive decay produces daughter isotopes that are also unstable, starting a chain of decays that ends in some stable isotope of lead.[6]

Nuclear energy was first discovered by French physicist Henri Becquerel in 1896, when he found that photographic plates stored in the dark near uranium were blackened like X-ray plates (X-rays had recently been discovered in 1895).[8]

Nuclear chemistry can be used as a form of alchemy to turn lead into gold or change any atom to any other atom (though this may require many intermediate steps).[7] Radionuclide (radioisotope) production often involves irradiation of another isotope (or more precisely a nuclide), with alpha particles, beta particles, or gamma rays. Nickel-62 has the highest binding energy per nucleon of any isotope. If an atom of lower average binding energy is changed into two atoms of higher average binding energy, energy is given off. Also, if two atoms of lower average binding energy fuse into an atom of higher average binding energy, energy is given off. The chart shows that fusion of hydrogen, the combination to form heavier atoms, releases energy, as does fission of uranium, the breaking up of a larger nucleus into smaller parts. Stability varies between isotopes: the isotope U-235 is much less stable than the more common U-238.

Nuclear energy is released by three exoenergetic (or exothermic) processes:

This practice is useful for other reasons, too: Stripping all the electrons from a heavy unstable nucleus (thus producing a bare nucleus) changes the lifetime of the nucleus, indicating that the nucleus cannot be treated independently (Experiments at the heavy ion accelerator GSI). This is also evident from phenomena like electron capture. Theoretically, in orbital models of heavy atoms, the electron orbits partially inside the nucleus (it doesn't orbit in a strict sense, but has a non-vanishing probability of being located inside the nucleus).

A nuclear decay happens to the nucleus, meaning that properties ascribed to the nucleus change in the event. In the field of physics the concept of "mass deficit" as a measure for "binding energy" means "mass deficit of the neutral atom" (not just the nucleus) and is a measure for stability of the whole atom.

The region of increasing binding energy is followed by a region of relative stability (saturation) in the sequence from magnesium through xenon. In this region, the nucleus has become large enough that nuclear forces no longer completely extend efficiently across its width. Attractive nuclear forces in this region, as atomic mass increases, are nearly balanced by repellent electromagnetic forces between protons, as the atomic number increases.

Finally, in elements heavier than xenon, there is a decrease in binding energy per nucleon as atomic number increases. In this region of nuclear size, electromagnetic repulsive forces are beginning to overcome the strong nuclear force attraction.

At the peak of binding energy, nickel-62 is the most tightly bound nucleus (per nucleon), followed by iron-58 and iron-56.[9] This is the approximate basic reason why iron and nickel are very common metals in planetary cores, since they are produced profusely as end products in supernovae and in the final stages of silicon burning in stars. However, it is not binding energy per defined nucleon (as defined above), which controls which exact nuclei are made, because within stars, neutrons are free to convert to protons to release even more energy, per generic nucleon, if the result is a stable nucleus with a larger fraction of protons. In fact, it has been argued that photodisintegration of 62Ni to form 56Fe may be energetically possible in an extremely hot star core, due to this beta decay conversion of neutrons to protons.[10] The conclusion is that at the pressure and temperature conditions in the cores of large stars, energy is released by converting all matter into 56Fe nuclei (ionized atoms). (However, at high temperatures not all matter will be in the lowest energy state.) This energetic maximum should also hold for ambient conditions, say T = 298 K and p = 1 atm, for neutral condensed matter consisting of 56Fe atoms—however, in these conditions nuclei of atoms are inhibited from fusing into the most stable and low energy state of matter.

It is generally believed that iron-56 is more common than nickel isotopes in the universe for mechanistic reasons, because its unstable progenitor nickel-56 is copiously made by staged build-up of 14 helium nuclei inside supernovas, where it has no time to decay to iron before being released into the interstellar medium in a matter of a few minutes, as the supernova explodes. However, nickel-56 then decays to cobalt-56 within a few weeks, then this radioisotope finally decays to iron-56 with a half life of about 77.3 days. The radioactive decay-powered light curve of such a process has been observed to happen in type II supernovae, such as SN 1987A. In a star, there are no good ways to create nickel-62 by alpha-addition processes, or else there would presumably be more of this highly stable nuclide in the universe.

Nuclear fusion produces energy by combining the very lightest elements into more tightly bound elements (such as hydrogen into helium), and nuclear fission produces energy by splitting the heaviest elements (such as uranium and plutonium) into more tightly bound elements (such as barium and krypton). Both processes produce energy, because middle-sized nuclei are the most tightly bound of all.

As seen above in the example of deuterium, nuclear binding energies are large enough that they may be easily measured as fractional mass deficits, according to the equivalence of mass and energy. The atomic binding energy is simply the amount of energy (and mass) released, when a collection of free nucleons are joined together to form a nucleus.

Nuclear binding energy can be computed from the difference in mass of a nucleus, and the sum of the masses of the number of free neutrons and protons that make up the nucleus. Once this mass difference, called the mass defect or mass deficiency, is known, Einstein's mass-energy equivalence formula E = mc² can be used to compute the binding energy of any nucleus. Early nuclear physicists used to refer to computing this value as a "packing fraction" calculation.

For example, the atomic mass unit (1 u) is defined as 1/12 of the mass of a 12C atom—but the atomic mass of a 1H atom (which is a proton plus electron) is 1.007825 u, so each nucleon in 12C has lost, on average, about 0.8% of its mass in the form of binding energy.

;

;  ;

;  ;

;  ;

;  .

.

The first term is called the saturation contribution and ensures that the binding energy per nucleon is the same for all nuclei to a first approximation. The term

is called the saturation contribution and ensures that the binding energy per nucleon is the same for all nuclei to a first approximation. The term  is a surface tension effect and is proportional to the number of nucleons that are situated on the nuclear surface; it is largest for light nuclei. The term

is a surface tension effect and is proportional to the number of nucleons that are situated on the nuclear surface; it is largest for light nuclei. The term  is the Coulomb electrostatic repulsion; this becomes more important as

is the Coulomb electrostatic repulsion; this becomes more important as  increases. The symmetry correction term

increases. The symmetry correction term  takes into account the fact that in the absence of other effects the most stable arrangement has equal numbers of protons and neutrons; this is because the n-p interaction in a nucleus is stronger than either the n-n or p-p interaction. The pairing term

takes into account the fact that in the absence of other effects the most stable arrangement has equal numbers of protons and neutrons; this is because the n-p interaction in a nucleus is stronger than either the n-n or p-p interaction. The pairing term  is purely empirical; it is + for even-even nuclei and - for odd-odd nuclei.

is purely empirical; it is + for even-even nuclei and - for odd-odd nuclei.

56Fe has the lowest nucleon-specific mass of the four nuclides listed in this table, but this does not imply it is the strongest bound atom per hadron, unless the choice of beginning hadrons is completely free. Iron releases the largest energy if any 56 nucleons are allowed to build a nuclide—changing one to another if necessary, The highest binding energy per hadron, with the hadrons starting as the same number of protons Z and total nucleons A as in the bound nucleus, is 62Ni. Thus, the true absolute value of the total binding energy of a nucleus depends on what we are allowed to construct the nucleus out of. If all nuclei of mass number A were to be allowed to be constructed of A neutrons, then Fe-56 would release the most energy per nucleon, since it has a larger fraction of protons than Ni-62. However, if nucleons are required to be constructed of only the same number of protons and neutrons that they contain, then nickel-62 is the most tightly bound nucleus, per nucleon.

In the table above it can be seen that the decay of a neutron, as well as the transformation of tritium into helium-3, releases energy; hence, it manifests a stronger bound new state when measured against the mass of an equal number of neutrons (and also a lighter state per number of total hadrons). Such reactions are not driven by changes in binding energies as calculated from previously fixed N and Z numbers of neutrons and protons, but rather in decreases in the total mass of the nuclide/per nucleon, with the reaction. (Note that the Binding Energy given above for hydrogen-1 is the atomic binding energy, not the nuclear binding energy which would be zero.)

The term nuclear binding energy may also refer to the energy balance in processes in which the nucleus splits into fragments composed of more than one nucleon, and in this case the binding energies for the fragments, as compared to the whole, will be higher. If new binding energy is available when light nuclei fuse, or when heavy nuclei split, either of these processes result in releases of the binding energy. This energy, available as nuclear energy, can be used to produce electricity (nuclear power) or as a nuclear weapon. When a large nucleus splits into pieces, excess energy is emitted as photons (gamma rays) and as kinetic energy of a number of different ejected particles (nuclear fission products).

The nuclear binding energies and forces are on the order of a million times greater than the electron binding energies of light atoms like hydrogen.[1]

The mass defect of a nucleus represents the mass of the energy of binding of the nucleus, and is the difference between the mass of a nucleus and the sum of the masses of the nucleons of which it is composed. Determining the relevant nuclear binding energy encompasses three steps of calculation, which involves the creation of mass defect by removing the mass as released energy.[2]

Introduction

Nuclear binding energy is explained by the basic principles involved in nuclear physics.

Nuclear energy

An absorption or release of nuclear energy occurs in nuclear reactions or radioactive decay; those that absorb energy are called endothermic reactions and those that release energy are exothermic reactions. Energy is consumed or liberated because of differences in the nuclear binding energy between the incoming and outgoing products of the nuclear transmutation.[3]The best-known classes of exothermic nuclear transmutations are fission and fusion. Nuclear energy may be liberated by atomic fission, when heavy atomic nuclei (like uranium and plutonium) are broken apart into lighter nuclei. The energy from fission is used to generate electric power in hundreds of locations worldwide. Nuclear energy is also released during atomic fusion, when light nuclei like hydrogen are combined to form heavier nuclei such as helium. The Sun and other stars use nuclear fusion to generate thermal energy which is later radiated from the surface, a type of stellar nucleosynthesis. In any exothermic nuclear process, nuclear mass might ultimately be converted to thermal energy, given off as heat, carries away the mass with it.

In order to quantify the energy released or absorbed in any nuclear transmutation, one must know the nuclear binding energies of the nuclear components involved in the transmutation.

The nuclear force

Electrons and nuclei are kept together by electrostatic attraction (negative attracts positive). Furthermore, electrons are sometimes shared by neighboring atoms or transferred to them (by processes of quantum physics), and this link between atoms is referred to as a chemical bond, and is responsible for the formation of all chemical compounds.[4]The force of electric attraction does not hold nuclei together, because all protons carry a positive charge and repel each other. Thus, electric forces do not hold nuclei together, because they act in the opposite direction. It has been established that binding neutrons to nuclei clearly requires a non-electrical attraction.[4]

Therefore, another force, called the nuclear force (or residual strong force) holds the nucleons of nuclei together. This force is a residuum of the strong interaction, which binds quarks into nucleons at an even smaller level of distance.

The nuclear force must be stronger than the electric repulsion at short distances, but weaker far away, or else different nuclei might tend to clump together. Therefore it has short-range characteristics. An analogy to the nuclear force is the force between two small magnets: magnets are very difficult to separate when stuck together, but once pulled a short distance apart, the force between them drops almost to zero.[4]

Unlike gravity or electrical forces, the nuclear force is effective only at very short distances. At greater distances, the electrostatic force dominates: the protons repel each other because they are positively charged, and like charges repel. For that reason, the protons forming the nuclei of ordinary hydrogen—for instance, in a balloon filled with hydrogen—do not combine to form helium (a process that also would require some to combine with electrons and become neutrons). They cannot get close enough for the nuclear force, which attracts them to each other, to become important. Only under conditions of extreme pressure and temperature (for example, within the core of a star), can such a process take place.[5]

Physics of nuclei

The nuclei of atoms are found in many different sizes. In hydrogen they contain just one proton, in deuterium or heavy hydrogen a proton and a neutron; in helium, two protons and two neutrons, and in carbon, nitrogen and oxygen - six, seven and eight of each particle, respectively. A helium nucleus weighs less than the sum of the weights of its components. The same phenomenon is found for carbon, nitrogen and oxygen. For example, the carbon nucleus is slightly lighter than three helium nuclei, which can combine to make a carbon nucleus. This illustrates the mass defect.Mass defect

The fundamental reason for the "mass defect" is Albert Einstein's formula E = m c2, expressing the equivalence of energy and mass. By this formula, adding energy also increases mass (both weight and inertia), whereas removing energy decreases mass.If a combination of particles contains extra energy—for instance, in a molecule of the explosive TNT—weighing it reveals some extra mass, compared to its end products after an explosion. (The weighing must be done after the products have been stopped and cooled, however, as the extra mass must escape from the system as heat before its loss can be noticed, in theory.) On the other hand, if one must inject energy to separate a system of particles into its components, then the initial weight is less than that of the components after they are separated. In the latter case, the energy injected is "stored" as potential energy, which shows as the increased mass of the components that store it. This is an example of the fact that energy of all types is seen in systems as mass, since mass and energy are equivalent, and each is a "property" of the other.

The latter scenario is the case with nuclei such as helium: to break them up into protons and neutrons, one must inject energy. On the other hand, if a process existed going in the opposite direction, by which hydrogen atoms could be combined to form helium, then energy would be released. The energy can be computed using E = Δm c2 for each nucleus, where Δm is the difference between the mass of the helium nucleus and the mass of four protons (plus two electrons, absorbed to create the neutrons of helium).

For elements heavier than oxygen, the energy that can be released by assembling them from lighter elements decreases, up to iron. For nuclei heavier than iron, one actually releases energy by breaking them up into 2 fragments. That is how energy is extracted by breaking up uranium nuclei in nuclear power reactors.

The reason the trend reverses after iron is the growing positive charge of the nuclei. The electric force may be weaker than the nuclear force, but its range is greater: in an iron nucleus, each proton repels the other 25 protons, while the nuclear force only binds close neighbors.

As nuclei grow bigger still, this disruptive effect becomes steadily more significant. By the time polonium is reached (84 protons), nuclei can no longer accommodate their large positive charge, but emit their excess protons quite rapidly in the process of alpha radioactivity—the emission of helium nuclei, each containing two protons and two neutrons. (Helium nuclei are an especially stable combination.) Because of this process, nuclei with more than 98 protons are not found naturally on Earth. The isotopes beyond uranium (atomic number 92) with the longest half-lives are plutonium-244 (80 million years) and curium-247 (16 million years).

Solar binding energy

The nuclear fusion process works as follows: five billion years ago, the new Sun formed when gravity pulled together a vast cloud of gas and dust, from which the Earth and other planets also arose. The gravitational pull released energy and heated the early Sun, much in the way Helmholtz proposed.Thermal energy appears as the motion of atoms and molecules: the higher the temperature of a collection of particles, the greater is their velocity and the more violent are their collisions. When the temperature at the center of the newly formed Sun became great enough for collisions between nuclei to overcome their electric repulsion, and bring them into the short range of the attractive nuclear force, nuclei began to stick together. When this began to happen, protons combined into deuterium and then helium, with some protons changing in the process to neutrons (plus positrons, positive electrons, which combine with electrons and are destroyed). This released nuclear energy now keeps up the high temperature of the Sun's core, and the heat also keeps the gas pressure high, keeping the Sun at its present size, and stopping gravity from compressing it any more. There is now a stable balance between gravity and pressure.

Different nuclear reactions may predominate at different stages of the Sun's existence, including the proton-proton reaction and the carbon-nitrogen cycle—which involves heavier nuclei, but whose final product is still the combination of protons to form helium.

A branch of physics, the study of controlled nuclear fusion, has tried since the 1950s to derive useful power from nuclear fusion reactions that combine small nuclei into bigger ones, typically to heat boilers, whose steam could turn turbines and produce electricity. Unfortunately, no earthly laboratory can match one feature of the solar powerhouse: the great mass of the Sun, whose weight keeps the hot plasma compressed and confines the nuclear furnace to the Sun's core. Instead, physicists use strong magnetic fields to confine the plasma, and for fuel they use heavy forms of hydrogen, which burn more easily. Magnetic traps can be rather unstable, and any plasma hot enough and dense enough to undergo nuclear fusion tends to slip out of them after a short time. Even with ingenious tricks, the confinement in most cases lasts only a small fraction of a second.

Combining nuclei

Small nuclei that are larger than hydrogen can combine into bigger ones and release energy, but in combining such nuclei, the amount of energy released is much smaller compared to hydrogen fusion. The reason is that while the overall process releases energy from letting the nuclear attraction do its work, energy must first be injected to force together positively charged protons, which also repel each other with their electric charge.[5]For elements that weigh more than iron (a nucleus with 26 protons), the fusion process no longer releases energy. In even heavier nuclei energy is consumed, not released, by combining similar sized nuclei. With such large nuclei, overcoming the electric repulsion (which affects all protons in the nucleus) requires more energy than what is released by the nuclear attraction (which is effective mainly between close neighbors). Conversely, energy could actually be released by breaking apart nuclei heavier than iron.[5]

With the nuclei of elements heavier than lead, the electric repulsion is so strong that some of them spontaneously eject positive fragments, usually nuclei of helium that form very stable combinations (alpha particles). This spontaneous break-up is one of the forms of radioactivity behavior exhibited by some nuclei.[5]

Nuclei heavier than lead (except for bismuth, thorium, uranium, and plutonium) spontaneously break up too quickly to appear in nature as primordial elements, though they can be produced artificially or as intermediates in the decay chains of lighter elements. Generally, the heavier the nuclei are, the faster they spontaneously decay.[5]

Iron nuclei are the most stable nuclei (in particular iron-56), and the best sources of energy are therefore nuclei whose weights are as far removed from iron as possible. One can combine the lightest ones—nuclei of hydrogen (protons)—to form nuclei of helium, and that is how the Sun generates its energy. Or else one can break up the heaviest ones—nuclei of uranium or plutonium—into smaller fragments, and that is what nuclear power reactors do.[5]

Nuclear binding energy

An example that illustrates nuclear binding energy is the nucleus of 12C (Carbon 12), which contains 6 protons and 6 neutrons. The protons are all positively charged and repel each other, but the nuclear force overcomes the repulsion and causes them to stick together. The nuclear force is a close-range force (it is very strongly inversely proportionate to distance), and virtually no effect of this force is observed outside the nucleus. The nuclear force also pulls neutrons together, or neutrons and protons.[6]The energy of the nucleus is negative with regard to the energy of the particles pulled apart to infinite distance (just like the gravitational energy of planets of the solar system), because energy must be utilized to split a nucleus into its individual protons and neutrons. Mass spectrometers have measured the masses of nuclei, which are always less than the sum of the masses of protons and neutrons that form them, and the difference—by the formula E = m c2—gives the binding energy of the nucleus.[6]

Nuclear fusion

The binding energy of helium is the energy source of the Sun and of most stars. The sun is composed of 74 percent hydrogen (measured by mass), an element whose nucleus is a single proton. Energy is released in the sun when 4 protons combine into a helium nucleus, a process in which two of them are also converted to neutrons.[6]The conversion of protons to neutrons is the result of another nuclear force, known as the weak (nuclear) force. The weak force, like the strong force, has a short range, but is much weaker than the strong force. The weak force tries to make the number of neutrons and protons into the most energetically stable configuration. For nuclei containing less than 40 particles, these numbers are usually about equal. Protons and neutrons are closely related and are sometimes collectively known as nucleons. As the number of particles increases toward a maximum of about 209, the number of neutrons to maintain stability begins to outstrip the number of protons, until the ratio of neutrons to protons is about three to two.[6]

The protons of hydrogen combine to helium only if they have enough velocity to overcome each other's mutual repulsion sufficiently to get within range of the strong nuclear attraction. This means that fusion only occurs within a very hot gas. Hydrogen hot enough for combining to helium requires an enormous pressure to keep it confined, but suitable conditions exist in the central regions of the Sun, where such pressure is provided by the enormous weight of the layers above the core, pressed inwards by the Sun's strong gravity. The process of combining protons to form helium is an example of nuclear fusion.[6]

The earth's oceans contain a large amount of hydrogen that could theoretically be used for fusion, and helium byproduct of fusion does not harm the environment, so some consider nuclear fusion a good alternative to supply humanity's energy needs. Experiments to generate electricity from fusion have so far have only partially succeeded. Sufficiently hot hydrogen must be ionized and confined. One technique is to use very strong magnetic fields, because charged particles (like those trapped in the Earth's radiation belt) are guided by magnetic field lines. Fusion experiments also rely on heavy hydrogen, which fuses more easily, and gas densities can be moderate. But even with these techniques far more net energy is consumed by the fusion experiments than is yielded by the process.[6]

The binding energy maximum and ways to approach it by decay

In the main isotopes of light nuclei, such as carbon, nitrogen and oxygen, the most stable combination of neutrons and of protons are when the numbers are equal (this continues to element 20, calcium). However, in heavier nuclei, the disruptive energy of protons increases, since they are confined to a tiny volume and repel each other. The energy of the strong force holding the nucleus together also increases, but at a slower rate, as if inside the nucleus, only nucleons close to each other are tightly bound, not ones more widely separated.[6]The net binding energy of a nucleus is that of the nuclear attraction, minus the disruptive energy of the electric force. As nuclei get heavier than helium, their net binding energy per nucleon (deduced from the difference in mass between the nucleus and the sum of masses of component nucleons) grows more and more slowly, reaching its peak at iron. As nucleons are added, the total nuclear binding energy always increases—but the total disruptive energy of electric forces (positive protons repelling other protons) also increases, and past iron, the second increase outweighs the first. Iron-56 (56Fe) is the most efficiently bound nucleus[6] meaning that it has the least average mass per nucleon. However, nickel-62 is the most tightly bound nucleus in terms of energy of binding per nucleon. (Nickel-62's higher energy of binding does not translate to a larger mean mass loss than Fe-56, because Ni-62 has a slightly higher ratio of neutrons/protons than does iron-56, and the presence of the heavier neutrons increases nickel-62's average mass per nucleon).

To reduce the disruptive energy, the weak interaction allows the number of neutrons to exceed that of protons—for instance, the main isotope of iron has 26 protons and 30 neutrons. Isotopes also exist where the number of neutrons differs from the most stable number for that number of nucleons. If the ratio of protons to neutrons is too far from stability, nucleons may spontaneously change from proton to neutron, or neutron to proton.

The two methods for this conversion are mediated by the weak force, and involve types of beta decay. In the simplest beta decay, neutrons are converted to protons by emitting a negative electron and an antineutrino. This is always possible outside a nucleus because neutrons are more massive than protons by an equivalent of about 2.5 electrons. In the opposite process, which only happens within a nucleus, and not to free particles, a proton may become a neutron by ejecting a positron. This is permitted if enough energy is available between parent and daughter nuclides to do this (the required energy difference is equal to 1.022 MeV, which is the mass of 2 electrons). If the mass difference between parent and daughter is less than this, a proton-rich nucleus may still convert protons to neutrons by the process of electron capture, in which a proton simply captures one of the atom's K orbital electrons, emits a neutrino, and becomes a neutron.[6]

Among the heaviest nuclei, starting with tellurium nuclei (element 52) containing 106 or more nucleons, electric forces may be so destabilizing that entire chunks of the nucleus may be ejected, usually as alpha particles, which consist of two protons and two neutrons (alpha particles are fast helium nuclei). (Beryllium-8 also decays, very quickly, into two alpha particles.) Alpha particles are extremely stable. This type of decay becomes more and more probable as elements rise in atomic weight past 106.

The curve of binding energy is a graph that plots the binding energy per nucleon against atomic mass. This curve has its main peak at iron and nickel and then slowly decreases again, and also a narrow isolated peak at helium, which as noted is very stable. The heaviest nuclei in nature, uranium 238U, are unstable, but having a lifetime of 4.5 billion years, close to the age of the Earth, they are still relatively abundant; they (and other nuclei heavier than iron) may have formed in a supernova explosion [7] preceding the formation of the solar system. The most common isotope of thorium, 232Th, also undergoes α particle emission, and its half-life (time over which half a number of atoms decays) is even longer, by several times. In each of these, radioactive decay produces daughter isotopes that are also unstable, starting a chain of decays that ends in some stable isotope of lead.[6]

Determining nuclear binding energy

Calculation can be employed to determine the nuclear binding energy of nuclei. The calculation involves determining the mass defect, converting it into energy, and expressing the result as energy per mole of atoms, or as energy per nucleon.[2]Conversion of mass defect into energy

Mass defect is defined as the difference between the mass of a nucleus, and the sum of the masses of the nucleons of which it is composed. The mass defect is determined by calculating three quantities.[2] These are: the actual mass of the nucleus, the composition of the nucleus (number of protons and of neutrons), and the masses of a proton and of a neutron. This is then followed by converting the mass defect into energy. This quantity is the nuclear binding energy, however it must be expressed as energy per mole of atoms or as energy per nucleon.[2]Fission and fusion

Nuclear energy is released by the splitting (fission) or merging (fusion) of the nuclei of atom(s). The conversion of nuclear mass-energy to a form of energy, which can remove some mass when the energy is removed, is consistent with the mass-energy equivalence formula ΔE = Δm c2, in which ΔE = energy release, Δm = mass defect, and c = the speed of light in a vacuum (a physical constant).Nuclear energy was first discovered by French physicist Henri Becquerel in 1896, when he found that photographic plates stored in the dark near uranium were blackened like X-ray plates (X-rays had recently been discovered in 1895).[8]

Nuclear chemistry can be used as a form of alchemy to turn lead into gold or change any atom to any other atom (though this may require many intermediate steps).[7] Radionuclide (radioisotope) production often involves irradiation of another isotope (or more precisely a nuclide), with alpha particles, beta particles, or gamma rays. Nickel-62 has the highest binding energy per nucleon of any isotope. If an atom of lower average binding energy is changed into two atoms of higher average binding energy, energy is given off. Also, if two atoms of lower average binding energy fuse into an atom of higher average binding energy, energy is given off. The chart shows that fusion of hydrogen, the combination to form heavier atoms, releases energy, as does fission of uranium, the breaking up of a larger nucleus into smaller parts. Stability varies between isotopes: the isotope U-235 is much less stable than the more common U-238.

Nuclear energy is released by three exoenergetic (or exothermic) processes:

- Radioactive decay, where a neutron or proton in the radioactive nucleus decays spontaneously by emitting either particles, electromagnetic radiation (gamma rays), or both. Note that for radioactive decay, it is not strictly necessary for the binding energy to increase. What is strictly necessary is that the mass decrease. If a neutron turns into a proton and the energy of the decay is less than 0.782343 MeV (such as rubidium-87 decaying to strontium-87), the average binding energy per nucleon will actually decrease.

- Fusion, two atomic nuclei fuse together to form a heavier nucleus

- Fission, the breaking of a heavy nucleus into two (or more rarely three) lighter nuclei

Binding energy for atoms

The binding energy of an atom (including its electrons) is not the same as the binding energy of the atom's nucleus. The measured mass deficits of isotopes are always listed as mass deficits of the neutral atoms of that isotope, and mostly in MeV. As a consequence, the listed mass deficits are not a measure for the stability or binding energy of isolated nuclei, but for the whole atoms. This has very practical reasons, because it is very hard to totally ionize heavy elements, i.e. strip them of all of their electrons.This practice is useful for other reasons, too: Stripping all the electrons from a heavy unstable nucleus (thus producing a bare nucleus) changes the lifetime of the nucleus, indicating that the nucleus cannot be treated independently (Experiments at the heavy ion accelerator GSI). This is also evident from phenomena like electron capture. Theoretically, in orbital models of heavy atoms, the electron orbits partially inside the nucleus (it doesn't orbit in a strict sense, but has a non-vanishing probability of being located inside the nucleus).

A nuclear decay happens to the nucleus, meaning that properties ascribed to the nucleus change in the event. In the field of physics the concept of "mass deficit" as a measure for "binding energy" means "mass deficit of the neutral atom" (not just the nucleus) and is a measure for stability of the whole atom.

Nuclear binding energy curve

In the periodic table of elements, the series of light elements from hydrogen up to sodium is observed to exhibit generally increasing binding energy per nucleon as the atomic mass increases. This increase is generated by increasing forces per nucleon in the nucleus, as each additional nucleon is attracted by other nearby nucleons, and thus more tightly bound to the whole.The region of increasing binding energy is followed by a region of relative stability (saturation) in the sequence from magnesium through xenon. In this region, the nucleus has become large enough that nuclear forces no longer completely extend efficiently across its width. Attractive nuclear forces in this region, as atomic mass increases, are nearly balanced by repellent electromagnetic forces between protons, as the atomic number increases.

Finally, in elements heavier than xenon, there is a decrease in binding energy per nucleon as atomic number increases. In this region of nuclear size, electromagnetic repulsive forces are beginning to overcome the strong nuclear force attraction.

At the peak of binding energy, nickel-62 is the most tightly bound nucleus (per nucleon), followed by iron-58 and iron-56.[9] This is the approximate basic reason why iron and nickel are very common metals in planetary cores, since they are produced profusely as end products in supernovae and in the final stages of silicon burning in stars. However, it is not binding energy per defined nucleon (as defined above), which controls which exact nuclei are made, because within stars, neutrons are free to convert to protons to release even more energy, per generic nucleon, if the result is a stable nucleus with a larger fraction of protons. In fact, it has been argued that photodisintegration of 62Ni to form 56Fe may be energetically possible in an extremely hot star core, due to this beta decay conversion of neutrons to protons.[10] The conclusion is that at the pressure and temperature conditions in the cores of large stars, energy is released by converting all matter into 56Fe nuclei (ionized atoms). (However, at high temperatures not all matter will be in the lowest energy state.) This energetic maximum should also hold for ambient conditions, say T = 298 K and p = 1 atm, for neutral condensed matter consisting of 56Fe atoms—however, in these conditions nuclei of atoms are inhibited from fusing into the most stable and low energy state of matter.

It is generally believed that iron-56 is more common than nickel isotopes in the universe for mechanistic reasons, because its unstable progenitor nickel-56 is copiously made by staged build-up of 14 helium nuclei inside supernovas, where it has no time to decay to iron before being released into the interstellar medium in a matter of a few minutes, as the supernova explodes. However, nickel-56 then decays to cobalt-56 within a few weeks, then this radioisotope finally decays to iron-56 with a half life of about 77.3 days. The radioactive decay-powered light curve of such a process has been observed to happen in type II supernovae, such as SN 1987A. In a star, there are no good ways to create nickel-62 by alpha-addition processes, or else there would presumably be more of this highly stable nuclide in the universe.

Measuring the binding energy

The fact that the maximum binding energy is found in medium-sized nuclei is a consequence of the trade-off in the effects of two opposing forces that have different range characteristics. The attractive nuclear force (strong nuclear force), which binds protons and neutrons equally to each other, has a limited range due to a rapid exponential decrease in this force with distance. However, the repelling electromagnetic force, which acts between protons to force nuclei apart, falls off with distance much more slowly (as the inverse square of distance). For nuclei larger than about four nucleons in diameter, the additional repelling force of additional protons more than offsets any binding energy that results between further added nucleons as a result of additional strong force interactions. Such nuclei become increasingly less tightly bound as their size increases, though most of them are still stable. Finally, nuclei containing more than 209 nucleons (larger than about 6 nucleons in diameter) are all too large to be stable, and are subject to spontaneous decay to smaller nuclei.Nuclear fusion produces energy by combining the very lightest elements into more tightly bound elements (such as hydrogen into helium), and nuclear fission produces energy by splitting the heaviest elements (such as uranium and plutonium) into more tightly bound elements (such as barium and krypton). Both processes produce energy, because middle-sized nuclei are the most tightly bound of all.

As seen above in the example of deuterium, nuclear binding energies are large enough that they may be easily measured as fractional mass deficits, according to the equivalence of mass and energy. The atomic binding energy is simply the amount of energy (and mass) released, when a collection of free nucleons are joined together to form a nucleus.

Nuclear binding energy can be computed from the difference in mass of a nucleus, and the sum of the masses of the number of free neutrons and protons that make up the nucleus. Once this mass difference, called the mass defect or mass deficiency, is known, Einstein's mass-energy equivalence formula E = mc² can be used to compute the binding energy of any nucleus. Early nuclear physicists used to refer to computing this value as a "packing fraction" calculation.

For example, the atomic mass unit (1 u) is defined as 1/12 of the mass of a 12C atom—but the atomic mass of a 1H atom (which is a proton plus electron) is 1.007825 u, so each nucleon in 12C has lost, on average, about 0.8% of its mass in the form of binding energy.

Semiempirical formula for nuclear binding energy

For a nucleus with A nucleons, including Z protons and N neutrons, a semi-empirical formula for the binding energy (BE) per nucleon is: ;

;  ;

;  ;

;  ;

;  .

.The first term

is called the saturation contribution and ensures that the binding energy per nucleon is the same for all nuclei to a first approximation. The term

is called the saturation contribution and ensures that the binding energy per nucleon is the same for all nuclei to a first approximation. The term  is a surface tension effect and is proportional to the number of nucleons that are situated on the nuclear surface; it is largest for light nuclei. The term

is a surface tension effect and is proportional to the number of nucleons that are situated on the nuclear surface; it is largest for light nuclei. The term  is the Coulomb electrostatic repulsion; this becomes more important as

is the Coulomb electrostatic repulsion; this becomes more important as  increases. The symmetry correction term

increases. The symmetry correction term  takes into account the fact that in the absence of other effects the most stable arrangement has equal numbers of protons and neutrons; this is because the n-p interaction in a nucleus is stronger than either the n-n or p-p interaction. The pairing term

takes into account the fact that in the absence of other effects the most stable arrangement has equal numbers of protons and neutrons; this is because the n-p interaction in a nucleus is stronger than either the n-n or p-p interaction. The pairing term  is purely empirical; it is + for even-even nuclei and - for odd-odd nuclei.

is purely empirical; it is + for even-even nuclei and - for odd-odd nuclei.

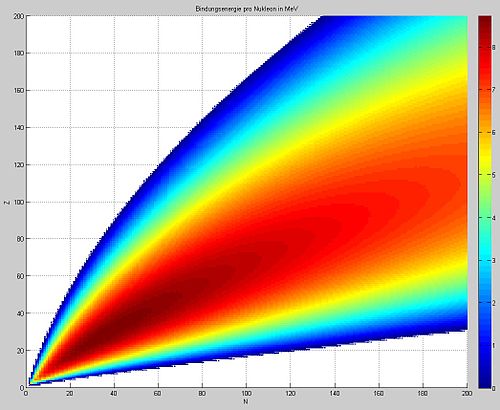

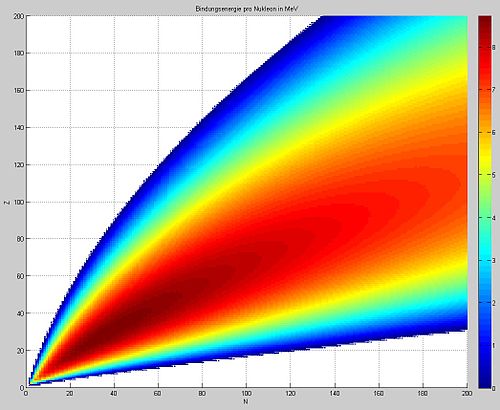

A graphical representation of the semi-

empirical binding energy formula. The

binding energy per nucleon in MeV (highest

numbers in dark red, in excess of 8.5 MeV

per nucleon) is plotted for various nuclides

as a function of Z, the atomic number

(y-axis), vs. N, the number of neutrons

(x-axis). The highest numbers are seen for

Z = 26 (iron).

empirical binding energy formula. The

binding energy per nucleon in MeV (highest

numbers in dark red, in excess of 8.5 MeV

per nucleon) is plotted for various nuclides

as a function of Z, the atomic number

(y-axis), vs. N, the number of neutrons

(x-axis). The highest numbers are seen for

Z = 26 (iron).

Example values deduced from experimentally measured atom nuclide masses

The following table lists some binding energies and mass defect values.[11] Notice also that we use 1 u = (931.494028 ± 0.000023) MeV. To calculate the binding energy we use the formula Z (mp + me) + N mn - mnuclide where Z denotes the number of protons in the nuclides and N their number of neutrons. We take mp = 938.2723 MeV, me = 0.5110 MeV and mn = 939.5656 MeV. The letter A denotes the sum of Z and N (number of nucleons in the nuclide). If we assume the reference nucleon has the mass of a neutron (so that all "total" binding energies calculated are maximal) we could define the total binding energy as the difference from the mass of the nucleus, and the mass of a collection of A free neutrons. In other words, it would be (Z + N) mn - mnuclide. The "total binding energy per nucleon" would be this value divided by A.| nuclide | Z | N | mass excess | total mass | total mass / A | total binding energy / A | mass defect | binding energy | binding energy / A |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 56Fe | 26 | 30 | -60.6054 MeV | 55.934937 u | 0.9988372 u | 9.1538 MeV | 0.528479 u | 492.275 MeV | 8.7906 MeV |

| 58Fe | 26 | 32 | -62.1534 MeV | 57.932276 u | 0.9988496 u | 9.1432 MeV | 0.547471 u | 509.966 MeV | 8.7925 MeV |

| 60Ni | 28 | 32 | -64.472 MeV | 59.93079 u | 0.9988464 u | 9.1462 MeV | 0.565612 u | 526.864 MeV | 8.7811 MeV |

| 62Ni | 28 | 34 | -66.7461 MeV | 61.928345 u | 0.9988443 u | 9.1481 MeV | 0.585383 u | 545.281 MeV | 8.7948 MeV |

56Fe has the lowest nucleon-specific mass of the four nuclides listed in this table, but this does not imply it is the strongest bound atom per hadron, unless the choice of beginning hadrons is completely free. Iron releases the largest energy if any 56 nucleons are allowed to build a nuclide—changing one to another if necessary, The highest binding energy per hadron, with the hadrons starting as the same number of protons Z and total nucleons A as in the bound nucleus, is 62Ni. Thus, the true absolute value of the total binding energy of a nucleus depends on what we are allowed to construct the nucleus out of. If all nuclei of mass number A were to be allowed to be constructed of A neutrons, then Fe-56 would release the most energy per nucleon, since it has a larger fraction of protons than Ni-62. However, if nucleons are required to be constructed of only the same number of protons and neutrons that they contain, then nickel-62 is the most tightly bound nucleus, per nucleon.

| nuclide | Z | N | mass excess | total mass | total mass / A | total binding energy / A | mass defect | binding energy | binding energy / A |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | 0 | 1 | 8.0716 MeV | 1.008665 u | 1.008665 u | 0.0000 MeV | 0 u | 0 MeV | 0 MeV |

| 1H | 1 | 0 | 7.2890 MeV | 1.007825 u | 1.007825 u | 0.7826 MeV | 0.0000000146 u | 0.0000136 MeV | 13.6 eV |

| 2H | 1 | 1 | 13.13572 MeV | 2.014102 u | 1.007051 u | 1.50346 MeV | 0.002388 u | 2.22452 MeV | 1.11226 MeV |

| 3H | 1 | 2 | 14.9498 MeV | 3.016049 u | 1.005350 u | 3.08815 MeV | 0.0091058 u | 8.4820 MeV | 2.8273 MeV |

| 3He | 2 | 1 | 14.9312 MeV | 3.016029 u | 1.005343 u | 3.09433 MeV | 0.0082857 u | 7.7181 MeV | 2.5727 MeV |

In the table above it can be seen that the decay of a neutron, as well as the transformation of tritium into helium-3, releases energy; hence, it manifests a stronger bound new state when measured against the mass of an equal number of neutrons (and also a lighter state per number of total hadrons). Such reactions are not driven by changes in binding energies as calculated from previously fixed N and Z numbers of neutrons and protons, but rather in decreases in the total mass of the nuclide/per nucleon, with the reaction. (Note that the Binding Energy given above for hydrogen-1 is the atomic binding energy, not the nuclear binding energy which would be zero.)