From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

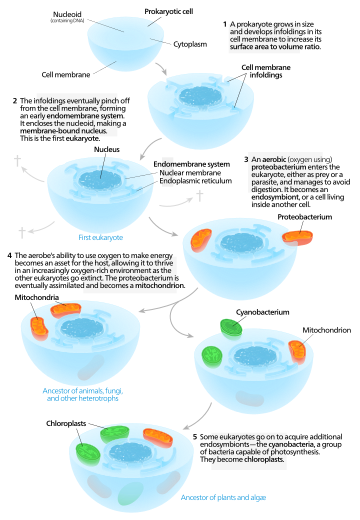

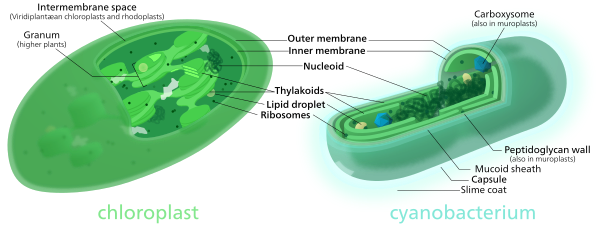

Symbiogenesis, or endosymbiotic theory, is an evolutionary theory that explains the origin of eukaryotic cells from prokaryotes. It states that several key organelles of eukaryotes originated as a symbiosis between separate single-celled organisms. According to this theory, mitochondria, plastids (for example chloroplasts), and possibly other organelles representing formerly free-living bacteria were taken inside another cell as an endosymbiont around 1.5 billion years ago. Molecular and biochemical evidence suggest that mitochondria developed from proteobacteria (in particular, Rickettsiales, the SAR11 clade,[1][2] or close relatives) and chloroplasts from cyanobacteria (in particular, nitrogen-fixing filamentous cyanobacteria[3][4]).

History

The endosymbiotic (Greek: ἔνδον endon "within", σύν syn "together" and βίωσις biosis "living") theories were first articulated by the Russian botanist Konstantin Mereschkowski in 1910,[5] although the fundamental elements of the theory were described in a paper five years earlier.[6][7] Mereschkowski was familiar with work by botanist Andreas Schimper, who had observed in 1883 that the division of chloroplasts in green plants closely resembled that of free-living cyanobacteria, and who had himself tentatively proposed (in a footnote) that green plants had arisen from a symbiotic union of two organisms.[8] Ivan Wallin extended the idea of an endosymbiotic origin to mitochondria in the 1920s.[9][10] A Russian botanist Boris Kozo-Polyansky was the first to explain the theory in terms of Darwinian evolution.[11] In his 1924 book Symbiogenesis: A New Principle of Evolution he wrote, "The theory of symbiogenesis is a theory of selection relying on the phenomenon of symbiosis."[12] These theories were initially dismissed or ignored. More detailed electron microscopic comparisons between cyanobacteria and chloroplasts (for example studies by Hans Ris published in 1961[13]), combined with the discovery that plastids and mitochondria contain their own DNA[14] (which by that stage was recognized to be the hereditary material of organisms) led to a resurrection of the idea in the 1960s.

The endosymbiotic theory was advanced and substantiated with microbiological evidence by Lynn Margulis in a 1967 paper, On the origin of mitosing cells.[15] In her 1981 work Symbiosis in Cell Evolution she argued that eukaryotic cells originated as communities of interacting entities, including endosymbiotic spirochaetes that developed into eukaryotic flagella and cilia. This last idea has not received much acceptance, because flagella lack DNA and do not show ultrastructural similarities to bacteria or archaea (see also: Evolution of flagella and Prokaryotic cytoskeleton). According to Margulis and Dorion Sagan,[16] "Life did not take over the globe by combat, but by networking" (i.e., by cooperation). The possibility that peroxisomes may have an endosymbiotic origin has also been considered, although they lack DNA. Christian de Duve proposed that they may have been the first endosymbionts, allowing cells to withstand growing amounts of free molecular oxygen in the Earth's atmosphere. However, it now appears that they may be formed de novo, contradicting the idea that they have a symbiotic origin.[17]

It is thought that over millennia these endosymbionts transferred some of their own DNA to the host cell's nucleus (called "endosymbiotic gene transfer") during the evolutionary transition from a symbiotic community to an instituted eukaryotic cell. The endosymbiotic theory is considered to be a type of saltational evolution.[18]

From endosymbionts to organelles

According to Keeling and Archibald,[19] the usual way to distinguish organelles from endosymbionts is by their reduced genome sizes. As an endosymbiont evolves into an organelle, most of their genes are transferred to the host cell genome. The host cell and organelle need to develop a transport mechanism that enables transfer back of the protein products needed by the organelle but now manufactured by the cell. However, using the example of the freshwater amoeboid Paulinella chromatophora, which contains chromatophores found to be evolved from cyanobacteria, these authors argue that this is not the only possible criterion, another one being that the host cell has assumed control of the regulation of the former endosymbiont's division, bringing it in synchrony with the cell's own division.[19] Nowack and her colleagues[20] performed gene sequencing on the chromatophore (1.02Mb) and found that only 867 proteins were encoded by these photosynthetic cells. Comparisons with their closest free living cyanobacteria of the genus Synechococcus (having a genome size of 3Mb with 3300 genes) revealed that chromatophores underwent a drastic genome shrinkage. Chromatophores contained genes that were accountable for photosynthesis but were deficient in genes that could carry out other biosynthetic functions signifying that these endosymbiotic cells were highly dependent on their hosts for their survival and growth mechanisms. Thus, these chromatophores were found to be non-functional for organelle-specific purposes when compared to mitochondria and plastids. This distinction could have promoted the early evolution of photosynthetic organelles.Evidence

Evidence that mitochondria and plastids arose from bacteria is as follows:[21][22][23]- New mitochondria and plastids are formed only through a process similar to binary fission.

- If a cell's mitochondria or chloroplasts are removed, they do not have the means to create new ones.[24] For example, in some algae, such as Euglena, the plastids can be destroyed by certain chemicals or prolonged absence of light without otherwise affecting the cell. In such a case, the plastids will not regenerate.

- Transport proteins called porins are found in the outer membranes of mitochondria and chloroplasts, are also found in bacterial cell membrane.[25][26][27]

- A membrane lipid cardiolipin is exclusively found in the inner mitochondrial membrane and bacterial cell membrane.[28]

- Both mitochondria and plastids contain single circular DNA that is different from that of the cell nucleus and that is similar to that of bacteria (both in their size and structure).

- The genomes, including the specific genes, are basically similar between mitochondria and the Rickettsial bacteria.[29]

- Genome comparisons indicate that cyanobacteria contributed to the genetic origin of plastids.[30]

- DNA sequence analysis and phylogenetic estimates suggest that nuclear DNA contains genes that probably came from plastids.

- These organelles' ribosomes are like those found in bacteria (70S).

- Proteins of organelle origin, like those of bacteria, use N-formylmethionine as the initiating amino acid.

- Much of the internal structure and biochemistry of plastids, for instance the presence of thylakoids and particular chlorophylls, is very similar to that of cyanobacteria. Phylogenetic estimates constructed with bacteria, plastids, and eukaryotic genomes also suggest that plastids are most closely related to cyanobacteria.

- Mitochondria have several enzymes and transport systems similar to those of bacteria.

- Some proteins encoded in the nucleus are transported to the organelle, and both mitochondria and plastids have small genomes compared to bacteria. This is consistent with an increased dependence on the eukaryotic host after forming an endosymbiosis. Most genes on the organellar genomes have been lost or moved to the nucleus. Most genes needed for mitochondrial and plastid function are located in the nucleus. Many originate from the bacterial endosymbiont.

- Plastids are present in very different groups of protists, some of which are closely related to forms lacking plastids. This suggests that if chloroplasts originated de novo, they did so multiple times, in which case their close similarity to each other is difficult to explain.

- Many of these protists contain "primary" plastids that have not yet been acquired from other plastid-containing eukaryotes.

- Among eukaryotes that acquired their plastids directly from bacteria (known as Archaeplastida), the glaucophyte algae have chloroplasts that strongly resemble cyanobacteria. In particular, they have a peptidoglycan cell wall between the two membranes.

Secondary endosymbiosis

Primary endosymbiosis involves the engulfment of a bacterium by another free living organism. Secondary endosymbiosis occurs when the product of primary endosymbiosis is itself engulfed and retained by another free living eukaryote. Secondary endosymbiosis has occurred several times and has given rise to extremely diverse groups of algae and other eukaryotes. Some organisms can take opportunistic advantage of a similar process, where they engulf an alga and use the products of its photosynthesis, but once the prey item dies (or is lost) the host returns to a free living state. Obligate secondary endosymbionts become dependent on their organelles and are unable to survive in their absence (for a review see McFadden 2001[31]). RedToL, the Red Algal Tree of Life Initiative funded by the National Science Foundation highlights the role red algae or Rhodophyta played in the evolution of our planet through secondary endosymbiosis.One possible secondary endosymbiosis in process has been observed by Okamoto & Inouye (2005). The heterotrophic protist Hatena behaves like a predator until it ingests a green alga, which loses its flagella and cytoskeleton, while Hatena, now a host, switches to photosynthetic nutrition, gains the ability to move towards light and loses its feeding apparatus.[32]

The process of secondary endosymbiosis left its evolutionary signature within the unique topography of plastid membranes. Secondary plastids are surrounded by three (in euglenophytes and some dinoflagellates) or four membranes (in haptophytes, heterokonts, cryptophytes, and chlorarachniophytes). The two additional membranes are thought to correspond to the plasma membrane of the engulfed alga and the phagosomal membrane of the host cell. The endosymbiotic acquisition of a eukaryote cell is represented in the cryptophytes; where the remnant nucleus of the red algal symbiont (the nucleomorph) is present between the two inner and two outer plastid membranes.[citation needed]

Despite the diversity of organisms containing plastids, the morphology, biochemistry, genomic organisation, and molecular phylogeny of plastid RNAs and proteins suggest a single origin of all extant plastids – although this theory is still debated.[33][34]

Some species including Pediculus humanus have multiple chromosomes in the mitochondrion. This and the phylogenetics of the genes encoded within the mitochondrion suggest that mitochondria have multiple ancestors, that these were acquired by endosymbiosis on several occasions rather than just once, and that there have been extensive mergers and rearrangements of genes on the several original mitochondrial chromosomes.[35]