From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

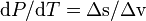

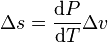

The Clausius–Clapeyron relation, named after Rudolf Clausius[1] and Benoît Paul Émile Clapeyron,[2] is a way of characterizing a discontinuous phase transition between two phases of matter of a single constituent. On a pressure–temperature (P–T) diagram, the line separating the two phases is known as the coexistence curve. The Clausius–Clapeyron relation gives the slope of the tangents to this curve. Mathematically,

is the slope of the tangent to the coexistence curve at any point,

is the slope of the tangent to the coexistence curve at any point,  is the specific latent heat,

is the specific latent heat,  is the temperature,

is the temperature,  is the specific volume change of the phase transition, and

is the specific volume change of the phase transition, and  is the specific entropy change of the phase transition.

is the specific entropy change of the phase transition.Derivations

Derivation from state postulate

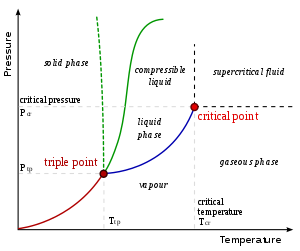

Using the state postulate, take the specific entropy for a homogeneous substance to be a function of specific volume

for a homogeneous substance to be a function of specific volume  and temperature

and temperature  .[3]:508

.[3]:508 is the pressure. Since pressure and temperature are constant, by definition the derivative of pressure with respect to temperature does not change.[4][5]:57, 62, 671 Therefore, the partial derivative of specific entropy may be changed into a total derivative

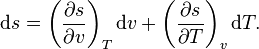

is the pressure. Since pressure and temperature are constant, by definition the derivative of pressure with respect to temperature does not change.[4][5]:57, 62, 671 Therefore, the partial derivative of specific entropy may be changed into a total derivative to a final phase

to a final phase  ,[3]:508 to obtain

,[3]:508 to obtain and

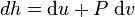

and  are respectively the change in specific entropy and specific volume. Given that a phase change is an internally reversible process, and that our system is closed, the first law of thermodynamics holds

are respectively the change in specific entropy and specific volume. Given that a phase change is an internally reversible process, and that our system is closed, the first law of thermodynamics holds is the internal energy of the system. Given constant pressure and temperature (during a phase change) and the definition of specific enthalpy

is the internal energy of the system. Given constant pressure and temperature (during a phase change) and the definition of specific enthalpy  , we obtain

, we obtain gives

gives ), we obtain[3]:508[6]

), we obtain[3]:508[6] , at any given point on the curve, to the function

, at any given point on the curve, to the function  of the specific latent heat

of the specific latent heat  , the temperature

, the temperature  , and the change in specific volume

, and the change in specific volume  .

.Derivation from Gibbs–Duhem relation[edit]

Suppose two phases, and

and  , are in contact and at equilibrium with each other. Their chemical potentials are related by

, are in contact and at equilibrium with each other. Their chemical potentials are related by is the specific entropy,

is the specific entropy,  is the specific volume, and

is the specific volume, and  is the molar mass) to obtain

is the molar mass) to obtainIdeal gas approximation at low temperatures

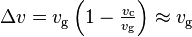

When the phase transition of a substance is between a gas phase and a condensed phase (liquid or solid), and occurs at temperatures much lower than the critical temperature of that substance, the specific volume of the gas phase greatly exceeds that of the condensed phase

greatly exceeds that of the condensed phase  . Therefore, one may approximate

. Therefore, one may approximate is the pressure,

is the pressure,  is the specific gas constant, and

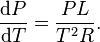

is the specific gas constant, and  is the temperature. Substituting into the Clapeyron equation

is the temperature. Substituting into the Clapeyron equation is the specific latent heat of the substance.

is the specific latent heat of the substance.Let

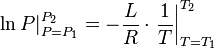

and

and  be any two points along the coexistence curve between two phases

be any two points along the coexistence curve between two phases  and

and  . In general,

. In general,  varies between any two such points, as a function of temperature. But if

varies between any two such points, as a function of temperature. But if  is constant,

is constant,Applications

Chemistry and chemical engineering

For transitions between a gas and a condensed phase with the approximations described above, the expression may be rewritten as is a constant. For a liquid-gas transition,

is a constant. For a liquid-gas transition,  is the specific latent heat (or specific enthalpy) of vaporization; for a solid-gas transition,

is the specific latent heat (or specific enthalpy) of vaporization; for a solid-gas transition,  is the specific latent heat of sublimation. If the latent heat is known, then knowledge of one point on the coexistence curve determines the rest of the curve. Conversely, the relationship between

is the specific latent heat of sublimation. If the latent heat is known, then knowledge of one point on the coexistence curve determines the rest of the curve. Conversely, the relationship between  and

and  is linear, and so linear regression is used to estimate the latent heat.

is linear, and so linear regression is used to estimate the latent heat.Meteorology and climatology

Atmospheric water vapor drives many important meteorologic phenomena (notably precipitation), motivating interest in its dynamics. The Clausius–Clapeyron equation for water vapor under typical atmospheric conditions (near standard temperature and pressure) is is saturation vapor pressure

is saturation vapor pressure is temperature

is temperature is the specific latent heat of evaporation of water

is the specific latent heat of evaporation of water is the gas constant of water vapor

is the gas constant of water vapor

, and therefore of the saturation vapor pressure

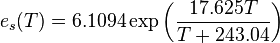

, and therefore of the saturation vapor pressure  , cannot be neglected in this application. Fortunately, the August-Roche-Magnus formula provides a very good approximation, using pressure in hPa and temperature in Celsius:

, cannot be neglected in this application. Fortunately, the August-Roche-Magnus formula provides a very good approximation, using pressure in hPa and temperature in Celsius:(This is also sometimes called the Magnus or Magnus-Tetens approximation, though this attribution is historically inaccurate.[9])

Under typical atmospheric conditions, the denominator of the exponent depends weakly on

(for which the unit is Celsius). Therefore, the August-Roche-Magnus equation implies that saturation water vapor pressure changes approximately exponentially with temperature under typical atmospheric conditions, and hence the water-holding capacity of the atmosphere increases by about 7% for every 1 °C rise in temperature.[10]

(for which the unit is Celsius). Therefore, the August-Roche-Magnus equation implies that saturation water vapor pressure changes approximately exponentially with temperature under typical atmospheric conditions, and hence the water-holding capacity of the atmosphere increases by about 7% for every 1 °C rise in temperature.[10]Example

One of the uses of this equation is to determine if a phase transition will occur in a given situation. Consider the question of how much pressure is needed to melt ice at a temperature below 0 °C. Note that water is unusual in that its change in volume upon melting is negative. We can assume

below 0 °C. Note that water is unusual in that its change in volume upon melting is negative. We can assume = 3.34×105 J/kg (latent heat of fusion for water),

= 3.34×105 J/kg (latent heat of fusion for water), = 273 K (absolute temperature), and

= 273 K (absolute temperature), and = −9.05×10−5 m³/kg (change in specific volume from solid to liquid),

= −9.05×10−5 m³/kg (change in specific volume from solid to liquid),

= −13.5 MPa/K.

= −13.5 MPa/K.

Second derivative

While the Clausius–Clapeyron relation gives the slope of the coexistence curve, it does not provide any information about its curvature or second derivative. The second derivative of the coexistence curve of phases 1 and 2 is given by [12] is the specific heat capacity at constant pressure,

is the specific heat capacity at constant pressure,  is the thermal expansion coefficient, and

is the thermal expansion coefficient, and  is the isothermal compressibility.

is the isothermal compressibility.

is

is  is the

is the  is the

is the

= −13.5 MPa/K.

= −13.5 MPa/K.