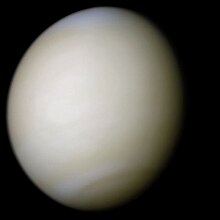

A real-colour image taken by Mariner 10 processed from two filters. The surface is obscured by thick sulfuric acid clouds.

| |||||||||||||

| Designations | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈviːnəs/ | ||||||||||||

| Adjectives | Venusian or (rarely) Cytherean, Venerean | ||||||||||||

| Orbital characteristics[2][4] | |||||||||||||

| Epoch J2000 | |||||||||||||

| Aphelion |

| ||||||||||||

| Perihelion |

| ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Eccentricity | 0.006772 | ||||||||||||

| 583.92 days | |||||||||||||

Average orbital speed

| 35.02 km/s | ||||||||||||

| 50.115° | |||||||||||||

| Inclination |

| ||||||||||||

| 76.680° | |||||||||||||

| 54.884° | |||||||||||||

| Satellites | None | ||||||||||||

| Physical characteristics | |||||||||||||

Mean radius

|

| ||||||||||||

| Flattening | 0 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Volume |

| ||||||||||||

| Mass |

| ||||||||||||

Mean density

| 5.243 g/cm3 | ||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| 10.36 km/s (6.44 mi/s) | |||||||||||||

Sidereal rotation period

| −243.025 d (retrograde) | ||||||||||||

Equatorial rotation velocity

| 6.52 km/h (1.81 m/s) | ||||||||||||

| 2.64° (for retrograde rotation) 177.36° (to orbit) | |||||||||||||

North pole right ascension

|

| ||||||||||||

North pole declination

| 67.16° | ||||||||||||

| Albedo | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| −4.92 to −2.98 | |||||||||||||

| 9.7″–66.0″ | |||||||||||||

| Atmosphere | |||||||||||||

Surface pressure

| 92 bar (9.2 MPa) | ||||||||||||

| Composition by volume |

| ||||||||||||

Venus is the second planet from the Sun, orbiting it every 224.7 Earth days. It has the longest rotation period (243 days) of any planet in the Solar System and rotates in the opposite direction to most other planets (meaning the Sun would rise in the west and set in the east). It does not have any natural satellites. It is named after the Roman goddess of love and beauty. It is the second-brightest natural object in the night sky after the Moon, reaching an apparent magnitude of −4.6 – bright enough to cast shadows at night and, rarely, visible to the naked eye in broad daylight. Orbiting within Earth's orbit, Venus is an inferior planet and never appears to venture far from the Sun; its maximum angular distance from the Sun (elongation) is 47.8°.

Venus is a terrestrial planet

and is sometimes called Earth's "sister planet" because of their

similar size, mass, proximity to the Sun, and bulk composition. It is

radically different from Earth in other respects. It has the densest atmosphere of the four terrestrial planets, consisting of more than 96% carbon dioxide. The atmospheric pressure

at the planet's surface is 92 times that of Earth, or roughly the

pressure found 900 m (3,000 ft) underwater on Earth. Venus is by far the

hottest planet in the Solar System, with a mean surface temperature of

735 K (462 °C; 863 °F), even though Mercury is closer to the Sun. Venus is shrouded by an opaque layer of highly reflective clouds of sulfuric acid, preventing its surface from being seen from space in visible light. It may have had water oceans in the past, but these would have vaporized as the temperature rose due to a runaway greenhouse effect. The water has probably photodissociated, and the free hydrogen has been swept into interplanetary space by the solar wind because of the lack of a planetary magnetic field. Venus's surface is a dry desertscape interspersed with slab-like rocks and is periodically resurfaced by volcanism.

As one of the brightest objects in the sky, Venus has been a

major fixture in human culture for as long as records have existed. It

has been made sacred to gods of many cultures, and has been a prime

inspiration for writers and poets as the morning star and evening star. Venus was the first planet to have its motions plotted across the sky, as early as the second millennium BC.

As the closest planet to Earth, Venus has been a prime target for

early interplanetary exploration. It was the first planet beyond Earth

visited by a spacecraft (Mariner 2 in 1962), and the first to be successfully landed on (by Venera 7

in 1970). Venus's thick clouds render observation of its surface

impossible in visible light, and the first detailed maps did not emerge

until the arrival of the Magellan orbiter in 1991. Plans have been proposed for rovers or more complex missions, but they are hindered by Venus's hostile surface conditions.

Physical characteristics

Size comparison with Earth

Venus is one of the four terrestrial planets

in the Solar System, meaning that it is a rocky body like Earth. It is

similar to Earth in size and mass, and is often described as Earth's

"sister" or "twin".

The diameter of Venus is 12,103.6 km (7,520.8 mi)—only 638.4 km

(396.7 mi) less than Earth's—and its mass is 81.5% of Earth's.

Conditions on the Venusian surface differ radically from those on Earth

because its dense atmosphere is 96.5% carbon dioxide, with most of the remaining 3.5% being nitrogen.

Geography

The Venusian surface was a subject of speculation until some of its secrets were revealed by planetary science in the 20th century. Venera landers in 1975 and 1982 returned images of a surface covered in sediment and relatively angular rocks. The surface was mapped in detail by Magellan in 1990–91. The ground shows evidence of extensive volcanism, and the sulfur in the atmosphere may indicate that there have been some recent eruptions.

About 80% of the Venusian surface is covered by smooth, volcanic

plains, consisting of 70% plains with wrinkle ridges and 10% smooth or

lobate plains. Two highland "continents"

make up the rest of its surface area, one lying in the planet's

northern hemisphere and the other just south of the equator. The

northern continent is called Ishtar Terra after Ishtar, the Babylonian goddess of love, and is about the size of Australia. Maxwell Montes, the highest mountain on Venus, lies on Ishtar Terra. Its peak is 11 km (7 mi) above the Venusian average surface elevation. The southern continent is called Aphrodite Terra, after the Greek

goddess of love, and is the larger of the two highland regions at

roughly the size of South America. A network of fractures and faults

covers much of this area.

The absence of evidence of lava flow accompanying any of the visible calderas remains an enigma. The planet has few impact craters, demonstrating that the surface is relatively young, approximately 300–600 million years old.

Venus has some unique surface features in addition to the impact

craters, mountains, and valleys commonly found on rocky planets. Among

these are flat-topped volcanic features called "farra",

which look somewhat like pancakes and range in size from 20 to 50 km

(12 to 31 mi) across, and from 100 to 1,000 m (330 to 3,280 ft) high;

radial, star-like fracture systems called "novae"; features with both

radial and concentric fractures resembling spider webs, known as "arachnoids"; and "coronae", circular rings of fractures sometimes surrounded by a depression. These features are volcanic in origin.

Most Venusian surface features are named after historical and mythological women. Exceptions are Maxwell Montes, named after James Clerk Maxwell, and highland regions Alpha Regio, Beta Regio, and Ovda Regio. The latter three features were named before the current system was adopted by the International Astronomical Union, the body which oversees planetary nomenclature.

The longitudes of physical features on Venus are expressed relative to its prime meridian.

The original prime meridian passed through the radar-bright spot at the

centre of the oval feature Eve, located south of Alpha Regio.

After the Venera missions were completed, the prime meridian was

redefined to pass through the central peak in the crater Ariadne.

Surface geology

False-colour image of Maat Mons with a vertical exaggeration of 22.5

Much of the Venusian surface appears to have been shaped by volcanic

activity. Venus has several times as many volcanoes as Earth, and it has

167 large volcanoes that are over 100 km (62 mi) across. The only

volcanic complex of this size on Earth is the Big Island of Hawaii. This is not because Venus is more volcanically active than Earth, but because its crust is older. Earth's oceanic crust is continually recycled by subduction at the boundaries of tectonic plates, and has an average age of about 100 million years, whereas the Venusian surface is estimated to be 300–600 million years old.

Several lines of evidence point to ongoing volcanic activity on Venus. During the Soviet Venera program, the Venera 9 orbiter obtained spectroscopic evidence of lightning on Venus, and the Venera 12 descent probe obtained additional evidence of lightning and thunder. The European Space Agency's Venus Express in 2007 detected whistler waves further confirming the occurrence of lightning on Venus.

One possibility is that ash from a volcanic eruption was generating the

lightning. Another piece of evidence comes from measurements of sulfur dioxide

concentrations in the atmosphere, which dropped by a factor of 10

between 1978 and 1986, jumped in 2006, and again declined 10-fold. This may mean that levels had been boosted several times by large volcanic eruptions.

In 2008 and 2009, the first direct evidence for ongoing volcanism was observed by Venus Express, in the form of four transient localized infrared hot spots within the rift zone Ganis Chasma, near the shield volcano Maat Mons.

Three of the spots were observed in more than one successive orbit.

These spots are thought to represent lava freshly released by volcanic

eruptions.

The actual temperatures are not known, because the size of the hot

spots could not be measured, but are likely to have been in the

800–1,100 K (527–827 °C; 980–1,520 °F) range, relative to a normal

temperature of 740 K (467 °C; 872 °F).

Impact craters on the surface of Venus (false-colour image reconstructed from radar data)

Almost a thousand impact craters on Venus are evenly distributed

across its surface. On other cratered bodies, such as Earth and the

Moon, craters show a range of states of degradation. On the Moon,

degradation is caused by subsequent impacts, whereas on Earth it is

caused by wind and rain erosion. On Venus, about 85% of the craters are

in pristine condition. The number of craters, together with their

well-preserved condition, indicates the planet underwent a global

resurfacing event about 300–600 million years ago, followed by a decay in volcanism.

Whereas Earth's crust is in continuous motion, Venus is thought to be

unable to sustain such a process. Without plate tectonics to dissipate

heat from its mantle, Venus instead undergoes a cyclical process in

which mantle temperatures rise until they reach a critical level that

weakens the crust. Then, over a period of about 100 million years,

subduction occurs on an enormous scale, completely recycling the crust.

Venusian craters range from 3 to 280 km (2 to 174 mi) in

diameter. No craters are smaller than 3 km, because of the effects of

the dense atmosphere on incoming objects. Objects with less than a

certain kinetic energy are slowed down so much by the atmosphere that they do not create an impact crater.

Incoming projectiles less than 50 m (160 ft) in diameter will fragment

and burn up in the atmosphere before reaching the ground.

Internal structure

The internal structure of Venus – the crust (outer layer), the mantle (middle layer) and the core (yellow inner layer)

Without seismic data or knowledge of its moment of inertia, little direct information is available about the internal structure and geochemistry of Venus. The similarity in size and density between Venus and Earth suggests they share a similar internal structure: a core, mantle, and crust.

Like that of Earth, the Venusian core is at least partially liquid

because the two planets have been cooling at about the same rate. The slightly smaller size of Venus means pressures are 24% lower in its deep interior than Earth's. The principal difference between the two planets is the lack of evidence for plate tectonics on Venus, possibly because its crust is too strong to subduct without water to make it less viscous.

This results in reduced heat loss from the planet, preventing it from

cooling and providing a likely explanation for its lack of an internally

generated magnetic field.

Instead, Venus may lose its internal heat in periodic major resurfacing events.

Atmosphere and climate

Cloud structure in the Venusian atmosphere in 1979, revealed by observations in the ultraviolet band by Pioneer Venus Orbiter

Venus has an extremely dense atmosphere composed of 96.5% carbon dioxide, 3.5% nitrogen, and traces of other gases, most notably sulfur dioxide.

The mass of its atmosphere is 93 times that of Earth's, whereas the

pressure at its surface is about 92 times that at Earth's—a pressure

equivalent to that at a depth of nearly 1 kilometre (0.62 mi) under

Earth's oceans. The density at the surface is 65 kg/m3, 6.5% that of water or 50 times as dense as Earth's atmosphere at 293 K (20 °C; 68 °F) at sea level. The CO

2-rich atmosphere generates the strongest greenhouse effect in the Solar System, creating surface temperatures of at least 735 K (462 °C; 864 °F). This makes Venus's surface hotter than Mercury's, which has a minimum surface temperature of 53 K (−220 °C; −364 °F) and maximum surface temperature of 700 K (427 °C; 801 °F), even though Venus is nearly twice Mercury's distance from the Sun and thus receives only 25% of Mercury's solar irradiance. This temperature is higher than that used for sterilization.

2-rich atmosphere generates the strongest greenhouse effect in the Solar System, creating surface temperatures of at least 735 K (462 °C; 864 °F). This makes Venus's surface hotter than Mercury's, which has a minimum surface temperature of 53 K (−220 °C; −364 °F) and maximum surface temperature of 700 K (427 °C; 801 °F), even though Venus is nearly twice Mercury's distance from the Sun and thus receives only 25% of Mercury's solar irradiance. This temperature is higher than that used for sterilization.

Studies have suggested that billions of years ago Venus's

atmosphere was much more like Earth's than it is now, and that there may

have been substantial quantities of liquid water on the surface, but

after a period of 600 million to several billion years,

a runaway greenhouse effect was caused by the evaporation of that

original water, which generated a critical level of greenhouse gases in

its atmosphere.

Although the surface conditions on Venus are no longer hospitable to

any Earthlike life that may have formed before this event, there is

speculation on the possibility that life exists in the upper cloud

layers of Venus, 50 km (31 mi) up from the surface, where the

temperature ranges between 303 and 353 K (30 and 80 °C; 86 and 176 °F)

but the environment is acidic.

Thermal inertia

and the transfer of heat by winds in the lower atmosphere mean that the

temperature of Venus's surface does not vary significantly between the

night and day sides, despite Venus's extremely slow rotation. Winds at

the surface are slow, moving at a few kilometres per hour, but because

of the high density of the atmosphere at the surface, they exert a

significant amount of force against obstructions, and transport dust and

small stones across the surface. This alone would make it difficult for

a human to walk through, even if the heat, pressure, and lack of oxygen

were not a problem.

Above the dense CO

2 layer are thick clouds consisting mainly of sulfuric acid, which is formed by sulfur dioxide and water through a chemical reaction resulting in sulfuric acid hydrate. Additionally, the atmosphere consists of approximately 1% ferric chloride. Other possible constituents of the cloud particles are ferric sulfate, aluminium chloride and phosphoric anhydride. Clouds at different levels have different compositions and particle size distributions. These clouds reflect and scatter about 90% of the sunlight that falls on them back into space, and prevent visual observation of Venus's surface. The permanent cloud cover means that although Venus is closer than Earth to the Sun, it receives less sunlight on the ground. Strong 300 km/h (185 mph) winds at the cloud tops go around Venus about every four to five Earth days. Winds on Venus move at up to 60 times the speed of its rotation, whereas Earth's fastest winds are only 10–20% rotation speed.

2 layer are thick clouds consisting mainly of sulfuric acid, which is formed by sulfur dioxide and water through a chemical reaction resulting in sulfuric acid hydrate. Additionally, the atmosphere consists of approximately 1% ferric chloride. Other possible constituents of the cloud particles are ferric sulfate, aluminium chloride and phosphoric anhydride. Clouds at different levels have different compositions and particle size distributions. These clouds reflect and scatter about 90% of the sunlight that falls on them back into space, and prevent visual observation of Venus's surface. The permanent cloud cover means that although Venus is closer than Earth to the Sun, it receives less sunlight on the ground. Strong 300 km/h (185 mph) winds at the cloud tops go around Venus about every four to five Earth days. Winds on Venus move at up to 60 times the speed of its rotation, whereas Earth's fastest winds are only 10–20% rotation speed.

The surface of Venus is effectively isothermal; it retains a constant temperature not only between day and night sides but between the equator and the poles. Venus's minute axial tilt—less than 3°, compared to 23° on Earth—also minimises seasonal temperature variation. The only appreciable variation in temperature occurs with altitude. The highest point on Venus, Maxwell Montes,

is therefore the coolest point on Venus, with a temperature of about

655 K (380 °C; 715 °F) and an atmospheric pressure of about 4.5 MPa

(45 bar). In 1995, the Magellan spacecraft imaged a highly reflective substance

at the tops of the highest mountain peaks that bore a strong

resemblance to terrestrial snow. This substance likely formed from a

similar process to snow, albeit at a far higher temperature. Too

volatile to condense on the surface, it rose in gaseous form to higher

elevations, where it is cooler and could precipitate. The identity of

this substance is not known with certainty, but speculation has ranged

from elemental tellurium to lead sulfide (galena).

The clouds of Venus may be capable of producing lightning.

The existence of lightning in the atmosphere of Venus has been

controversial since the first suspected bursts were detected by the

Soviet Venera probes. In 2006–07, Venus Express clearly detected whistler mode waves, the signatures of lightning. Their intermittent

appearance indicates a pattern associated with weather activity.

According to these measurements, the lightning rate is at least half of

that on Earth. In 2007, Venus Express discovered that a huge double atmospheric vortex exists at the south pole.

Venus Express also discovered, in 2011, that an ozone layer exists high in the atmosphere of Venus. On 29 January 2013, ESA scientists reported that the ionosphere of Venus streams outwards in a manner similar to "the ion tail seen streaming from a comet under similar conditions."

In December 2015 and to a lesser extent in April and May 2016, researchers working on Japan's Akatsuki

mission observed bow shapes in the atmosphere of Venus. This was

considered direct evidence of the existence of perhaps the largest

stationary gravity waves in the solar system.

Atmospheric composition

The composition of the atmosphere of Venus based on HITRAN data created using HITRAN on the Web system.

Green colour – water vapour, red – carbon dioxide, WN – wavenumber (other colours have different meanings, lower wavelengths on the right, higher on the left).

Magnetic field and core

In 1967, Venera 4 found Venus's magnetic field to be much weaker than that of Earth. This magnetic field is induced by an interaction between the ionosphere and the solar wind, rather than by an internal dynamo as in the Earth's core. Venus's small induced magnetosphere provides negligible protection to the atmosphere against cosmic radiation.

The lack of an intrinsic magnetic field at Venus was surprising,

given that it is similar to Earth in size, and was expected also to

contain a dynamo at its core. A dynamo requires three things: a conducting liquid, rotation, and convection.

The core is thought to be electrically conductive and, although its

rotation is often thought to be too slow, simulations show it is

adequate to produce a dynamo. This implies that the dynamo is missing because of a lack of convection

in Venus's core. On Earth, convection occurs in the liquid outer layer

of the core because the bottom of the liquid layer is much hotter than

the top. On Venus, a global resurfacing event may have shut down plate

tectonics and led to a reduced heat flux through the crust. This caused

the mantle temperature to increase, thereby reducing the heat flux out

of the core. As a result, no internal geodynamo is available to drive a

magnetic field. Instead, the heat from the core is being used to reheat

the crust.

One possibility is that Venus has no solid inner core,

or that its core is not cooling, so that the entire liquid part of the

core is at approximately the same temperature. Another possibility is

that its core has already completely solidified. The state of the core

is highly dependent on the concentration of sulfur, which is unknown at present.

The weak magnetosphere around Venus means that the solar wind

is interacting directly with its outer atmosphere. Here, ions of

hydrogen and oxygen are being created by the dissociation of neutral

molecules from ultraviolet radiation. The solar wind then supplies

energy that gives some of these ions sufficient velocity to escape

Venus's gravity field. This erosion process results in a steady loss of

low-mass hydrogen, helium, and oxygen ions, whereas higher-mass

molecules, such as carbon dioxide, are more likely to be retained.

Atmospheric erosion by the solar wind probably led to the loss of most

of Venus's water during the first billion years after it formed. The erosion has increased the ratio of higher-mass deuterium to lower-mass hydrogen in the atmosphere 100 times compared to the rest of the solar system.

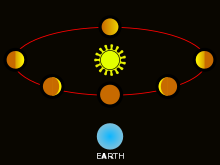

Orbit and rotation

Venus orbits the Sun at an average distance of about 108 million kilometres (about 0.7 AU)

and completes an orbit every 224.7 days. Venus is the second planet

from the Sun and orbits the Sun approximately 1.6 times (yellow trail)

in Earth's 365 days (blue trail)

Venus orbits the Sun at an average distance of about 0.72 AU (108 million km; 67 million mi), and completes an orbit every 224.7 days. Although all planetary orbits are elliptical, Venus's orbit is the closest to circular, with an eccentricity of less than 0.01. When Venus lies between Earth and the Sun in inferior conjunction, it makes the closest approach to Earth of any planet at an average distance of 41 million km (25 million mi). The planet reaches inferior conjunction every 584 days, on average. Because of the decreasing eccentricity of Earth's orbit,

the minimum distances will become greater over tens of thousands of

years. From the year 1 to 5383, there are 526 approaches less than

40 million km; then there are none for about 60,158 years.

All the planets in the Solar System orbit the Sun in a

counterclockwise direction as viewed from above Earth's north pole. Most

planets also rotate on their axes in an anti-clockwise direction, but

Venus rotates clockwise in retrograde rotation

once every 243 Earth days—the slowest rotation of any planet. Because

its rotation is so slow, Venus is very close to spherical. A Venusian sidereal day

thus lasts longer than a Venusian year (243 versus 224.7 Earth days).

Venus's equator rotates at 6.52 km/h (4.05 mph), whereas Earth's rotates

at 1,669.8 km/h (1,037.6 mph). Venus's rotation has slowed down in the 16 years between the Magellan spacecraft and Venus Express visits; each Venusian sidereal day has increased by 6.5 minutes in that time span. Because of the retrograde rotation, the length of a solar day on Venus is significantly shorter than the sidereal day, at 116.75 Earth days (making the Venusian solar day shorter than Mercury's 176 Earth days). One Venusian year is about 1.92 Venusian solar days. To an observer on the surface of Venus, the Sun would rise in the west and set in the east, although Venus's opaque clouds prevent observing the Sun from the planet's surface.

Venus may have formed from the solar nebula

with a different rotation period and obliquity, reaching its current

state because of chaotic spin changes caused by planetary perturbations

and tidal

effects on its dense atmosphere, a change that would have occurred over

the course of billions of years. The rotation period of Venus may

represent an equilibrium state between tidal locking to the Sun's

gravitation, which tends to slow rotation, and an atmospheric tide

created by solar heating of the thick Venusian atmosphere.

The 584-day average interval between successive close approaches to Earth is almost exactly equal to 5 Venusian solar days, but the hypothesis of a spin–orbit resonance with Earth has been discounted.

Venus has no natural satellites. It has several trojan asteroids: the quasi-satellite 2002 VE68 and two other temporary trojans, 2001 CK32 and 2012 XE133. In the 17th century, Giovanni Cassini reported a moon orbiting Venus, which was named Neith and numerous sightings were reported over the following 200 years, but most were determined to be stars in the vicinity. Alex Alemi's and David Stevenson's 2006 study of models of the early Solar System at the California Institute of Technology shows Venus likely had at least one moon created by a huge impact event billions of years ago.

About 10 million years later, according to the study, another impact

reversed the planet's spin direction and caused the Venusian moon

gradually to spiral inward until it collided with Venus.

If later impacts created moons, these were removed in the same way. An

alternative explanation for the lack of satellites is the effect of

strong solar tides, which can destabilize large satellites orbiting the

inner terrestrial planets.

Observation

Venus

is always brighter than all other planets or stars as seen from Earth.

The second brightest object on the image is Jupiter.

To the naked eye, Venus appears as a white point of light brighter than any other planet or star (apart from the Sun). The planet's mean apparent magnitude is -4.14 with a standard deviation of 0.31.

The brightest magnitude occurs during crescent phase about one month

before or after inferior conjunction. Venus fades to about magnitude −3

when it is backlit by the Sun. The planet is bright enough to be seen in a clear midday sky and is more easily visible when the Sun is low on the horizon or setting. As an inferior planet, it always lies within about 47° of the Sun.

Venus "overtakes" Earth every 584 days as it orbits the Sun.

As it does so, it changes from the "Evening Star", visible after

sunset, to the "Morning Star", visible before sunrise. Although Mercury, the other inferior planet, reaches a maximum elongation

of only 28° and is often difficult to discern in twilight, Venus is

hard to miss when it is at its brightest. Its greater maximum elongation

means it is visible in dark skies long after sunset. As the brightest

point-like object in the sky, Venus is a commonly misreported "unidentified flying object".

Phases

The phases of Venus and evolution of its apparent diameter

As it orbits the Sun, Venus displays phases like those of the Moon in a telescopic view. The planet appears as a small and "full" disc when it is on the opposite side of the Sun (at superior conjunction). Venus shows a larger disc and "quarter phase" at its maximum elongations

from the Sun, and appears its brightest in the night sky. The planet

presents a much larger thin "crescent" in telescopic views as it passes

along the near side between Earth and the Sun. Venus displays its

largest size and "new phase" when it is between Earth and the Sun (at

inferior conjunction). Its atmosphere is visible through telescopes by

the halo of sunlight refracted around it.

Transits

The Venusian orbit is slightly inclined relative to Earth's orbit;

thus, when the planet passes between Earth and the Sun, it usually does

not cross the face of the Sun. Transits of Venus occur when the planet's inferior conjunction coincides with its presence in the plane of Earth's orbit. Transits of Venus occur in cycles of 243 years with the current pattern of transits being pairs of transits separated by eight years, at intervals of about 105.5 years or 121.5 years—a pattern first discovered in 1639 by the English astronomer Jeremiah Horrocks.

The latest pair was June 8, 2004 and June 5–6, 2012. The transit could be watched live from many online outlets or observed locally with the right equipment and conditions.

The preceding pair of transits occurred in December 1874 and December 1882; the following pair will occur in December 2117 and December 2125. The oldest film known is the 1874 Passage de Venus,

showing the 1874 Venus transit of the sun. Historically, transits of

Venus were important, because they allowed astronomers to determine the

size of the astronomical unit, and hence the size of the Solar System as shown by Horrocks in 1639. Captain Cook's exploration of the east coast of Australia came after he had sailed to Tahiti in 1768 to observe a transit of Venus.

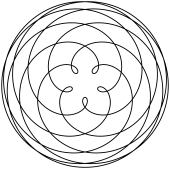

Pentagram of Venus

The

pentagram of Venus. Earth is positioned at the centre of the diagram,

and the curve represents the direction and distance of Venus as a

function of time.

The pentagram of Venus is the path that Venus makes as observed from Earth. Successive inferior conjunctions of Venus repeat very near a 13:8 orbital resonance

(Earth orbits 8 times for every 13 orbits of Venus), shifting 144° upon

sequential inferior conjunctions. The resonance 13:8 ratio is

approximate. 8/13 is approximately 0.615385 while Venus orbits the Sun

in 0.615187 years.

Daylight apparitions

Naked eye observations of Venus during daylight hours exist in several anecdotes and records. Astronomer Edmund Halley

calculated its maximum naked eye brightness in 1716, when many

Londoners were alarmed by its appearance in the daytime. French emperor Napoleon Bonaparte once witnessed a daytime apparition of the planet while at a reception in Luxembourg. Another historical daytime observation of the planet took place during the inauguration of the American president Abraham Lincoln in Washington, D.C., on 4 March 1865. Although naked eye visibility of Venus's phases is disputed, records exist of observations of its crescent.

Ashen light

A long-standing mystery of Venus observations is the so-called ashen light—an

apparent weak illumination of its dark side, seen when the planet is in

the crescent phase. The first claimed observation of ashen light was

made in 1643, but the existence of the illumination has never been

reliably confirmed. Observers have speculated it may result from

electrical activity in the Venusian atmosphere, but it could be

illusory, resulting from the physiological effect of observing a bright,

crescent-shaped object.

Studies

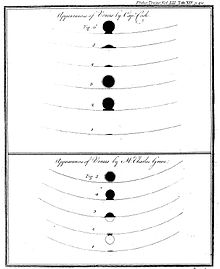

Early studies

The "black drop effect" as recorded during the 1769 transit

Though some ancient civilizations referred to Venus both as the

"morning star" and as the "evening star", names that reflect the

assumption that these were two separate objects, the earliest recorded

observations of Venus by the ancient Sumerians show that they recognized Venus as a single object, associated it with the goddess Inanna. Inanna's movements in several of her myths, including Inanna and Shukaletuda and Inanna's Descent into the Underworld appear to parallel the motion of the planet Venus. The Venus tablet of Ammisaduqa, believed to have been compiled around the mid-seventeenth century BCE,

shows the Babylonians understood the two were a single object, referred

to in the tablet as the "bright queen of the sky", and could support

this view with detailed observations.

The Chinese historically referred to the morning Venus as "the Great White" (Tài-bái 太白) or "the Opener (Starter) of Brightness" (Qǐ-míng 啟明), and the evening Venus as "the Excellent West One" (Cháng-gēng 長庚).

The ancient Greeks also initially believed Venus to be two separate stars: Phosphorus, the morning star, and Hesperus, the evening star. Pliny the Elder credited the realization that they were a single object to Pythagoras in the sixth century BCE, while Diogenes Laertius argued that Parmenides was probably responsible for this rediscovery. Though they recognized Venus as a single object, the ancient Romans continued to designate the morning aspect of Venus as Lucifer, literally "Light-Bringer", and the evening aspect as Vesper, both of which are literal translations of their traditional Greek names.

In the second century, in his astronomical treatise Almagest, Ptolemy theorized that both Mercury and Venus are located between the Sun and the Earth. The 11th century Persian astronomer Avicenna claimed to have observed the transit of Venus, which later astronomers took as confirmation of Ptolemy's theory. In the 12th century, the Andalusian astronomer Ibn Bajjah

observed "two planets as black spots on the face of the Sun"; these

were later identified as the transits of Venus and Mercury by the Maragha astronomer Qotb al-Din Shirazi in the 13th century, though this identification cannot be true as there were no Venus transits in Ibn Bajjah's lifetime.

When the Italian physicist Galileo Galilei first observed the planet in the early 17th century, he found it showed phases

like the Moon, varying from crescent to gibbous to full and vice versa.

When Venus is furthest from the Sun in the sky, it shows a half-lit phase,

and when it is closest to the Sun in the sky, it shows as a crescent or

full phase. This could be possible only if Venus orbited the Sun, and

this was among the first observations to clearly contradict the Ptolemaic geocentric model that the Solar System was concentric and centred on Earth.

The 1639 transit of Venus was accurately predicted by Jeremiah Horrocks and observed by him and his friend, William Crabtree, at each of their respective homes, on 4 December 1639 (24 November under the Julian calendar in use at that time).

The atmosphere of Venus was discovered in 1761 by Russian polymath Mikhail Lomonosov. Venus's atmosphere was observed in 1790 by German astronomer Johann Schröter.

Schröter found when the planet was a thin crescent, the cusps extended

through more than 180°. He correctly surmised this was due to scattering of sunlight in a dense atmosphere. Later, American astronomer Chester Smith Lyman observed a complete ring around the dark side of the planet when it was at inferior conjunction, providing further evidence for an atmosphere.

The atmosphere complicated efforts to determine a rotation period for

the planet, and observers such as Italian-born astronomer Giovanni Cassini and Schröter incorrectly estimated periods of about 24 h from the motions of markings on the planet's apparent surface.

Ground-based research

Modern telescopic view of Venus from Earth's surface

Little more was discovered about Venus until the 20th century. Its

almost featureless disc gave no hint what its surface might be like, and

it was only with the development of spectroscopic, radar and ultraviolet observations that more of its secrets were revealed. The first ultraviolet observations were carried out in the 1920s, when Frank E. Ross found that ultraviolet photographs revealed considerable detail that was absent in visible and infrared radiation. He suggested this was due to a dense, yellow lower atmosphere with high cirrus clouds above it.

Spectroscopic observations in the 1900s gave the first clues about the Venusian rotation. Vesto Slipher tried to measure the Doppler shift

of light from Venus, but found he could not detect any rotation. He

surmised the planet must have a much longer rotation period than had

previously been thought. Later work in the 1950s showed the rotation was retrograde. Radar observations

of Venus were first carried out in the 1960s, and provided the first

measurements of the rotation period, which were close to the modern

value.

Radar observations in the 1970s revealed details of the Venusian

surface for the first time. Pulses of radio waves were beamed at the

planet using the 300 m (980 ft) radio telescope at Arecibo Observatory, and the echoes revealed two highly reflective regions, designated the Alpha and Beta regions. The observations also revealed a bright region attributed to mountains, which was called Maxwell Montes. These three features are now the only ones on Venus that do not have female names.

Exploration

Artist's impression of Mariner 2, launched in 1962, a skeletal, bottle-shaped spacecraft with a large radio dish on top

The first robotic space probe mission to Venus, and the first to any planet, began with the Soviet Venera program in 1961. The United States' exploration of Venus had its first success with the Mariner 2 mission on 14 December 1962, becoming the world's first successful interplanetary mission, passing 34,833 km (21,644 mi) above the surface of Venus, and gathering data on the planet's atmosphere.

180-degree panorama of Venus's surface from the Soviet Venera 9

lander, 1975. Black-and-white image of barren, black, slate-like rocks

against a flat sky. The ground and the probe are the focus. Several

lines are missing due to a simultaneous transmission of the scientific

data

On 18 October 1967, the Soviet Venera 4 successfully entered the atmosphere and deployed science experiments. Venera 4 showed the surface temperature was hotter than Mariner 2 had calculated, at almost 500 °C, determined that the atmosphere is 95% carbon dioxide (CO

2), and discovered that Venus's atmosphere was considerably denser than Venera 4's designers had anticipated. The joint Venera 4–Mariner 5 data were analysed by a combined Soviet–American science team in a series of colloquia over the following year, in an early example of space cooperation.

2), and discovered that Venus's atmosphere was considerably denser than Venera 4's designers had anticipated. The joint Venera 4–Mariner 5 data were analysed by a combined Soviet–American science team in a series of colloquia over the following year, in an early example of space cooperation.

In 1974, Mariner 10

swung by Venus on its way to Mercury and took ultraviolet photographs

of the clouds, revealing the extraordinarily high wind speeds in the

Venusian atmosphere.

Global view of Venus in ultraviolet light done by Mariner 10.

In 1975, the Soviet Venera 9 and 10

landers transmitted the first images from the surface of Venus, which

were in black and white. In 1982 the first colour images of the surface

were obtained with the Soviet Venera 13 and 14 landers.

NASA obtained additional data in 1978 with the Pioneer Venus project that consisted of two separate missions: Pioneer Venus Orbiter and Pioneer Venus Multiprobe. The successful Soviet Venera program came to a close in October 1983, when Venera 15 and 16 were placed in orbit to conduct detailed mapping of 25% of Venus's terrain (from the north pole to 30°N latitude)

Several other Venus flybys took place in the 1980s and 1990s that increased the understanding of Venus, including Vega 1 (1985), Vega 2 (1985), Galileo (1990), Magellan (1994), Cassini–Huygens (1998), and MESSENGER (2006). Then, Venus Express by the European Space Agency (ESA) entered orbit around Venus in April 2006. Equipped with seven scientific instruments, Venus Express provided unprecedented long-term observation of Venus's atmosphere. ESA concluded that mission in December 2014.

As of 2016, Japan's Akatsuki is in a highly elliptical orbit around Venus since 7 December 2015, and there are several probing proposals under study by Roscosmos, NASA, and India's ISRO.

In 2016, NASA announced that it was planning a rover, the Automaton Rover for Extreme Environments, designed to survive for an extended time in Venus's environmental conditions. It would be controlled by a mechanical computer and driven by wind power.

In culture

Venus is portrayed just to the right of the large cypress tree in Vincent van Gogh's 1889 painting The Starry Night.

Venus is a primary feature of the night sky, and so has been of remarkable importance in mythology, astrology and fiction throughout history and in different cultures. Classical poets such as Homer, Sappho, Ovid and Virgil spoke of the star and its light. Romantic poets such as William Blake, Robert Frost, Alfred Lord Tennyson and William Wordsworth wrote odes to it.

Because the movements of Venus appear to be discontinuous (it

disappears due to its proximity to the sun, for many days at a time, and

then reappears on the other horizon), some cultures did not recognize

Venus as single entity; instead, they assumed it to be two separate

stars on each horizon: the morning and evening star. Nonetheless, a cylinder seal from the Jemdet Nasr period indicates that the ancient Sumerians already knew that the morning and evening stars were the same celestial object. The Sumerians associated the planet with the goddess Inanna (known as Ishtar by the later Akkadians and Babylonians), and their myths of Inanna are often allegories for the apparent motions and cycles of the planet. In the Old Babylonian period, the planet Venus was known as Ninsi'anna, and later as Dilbat.

The name "Ninsi'anna" translates to "divine lady, illumination of

heaven", which refers to Venus as the brightest visible "star". Earlier

spellings of the name were written with the cuneiform

sign si4 (= SU, meaning "to be red"), and the original meaning may have

been "divine lady of the redness of heaven", in reference to the color

of the morning and evening sky. Venus is described in Babylonian cuneiform texts such as the Venus tablet of Ammisaduqa, which relates observations that possibly date from 1600 BC.

In Chinese the planet is called Jīn-xīng (金星), the golden planet of the metal element. In India Shukra Graha ("the planet Shukra") which is named after a powerful saint Shukra. Shukra which is used in Indian Vedic astrology means "clear, pure" or "brightness, clearness" in Sanskrit. One of the nine Navagraha, it is held to affect wealth, pleasure and reproduction; it was the son of Bhrgu, preceptor of the Daityas, and guru of the Asuras. The word Shukra is also associated with semen, or generation. Venus is known as Kejora in Indonesian and Malay. Modern Chinese, Japanese and Korean cultures refer to the planet literally as the "metal star" (金星), based on the Five elements.

The Ancient Egyptians and Greeks believed Venus to be two separate bodies, a morning star and an evening star. The Egyptians knew the morning star as Tioumoutiri and the evening star as Ouaiti. The Greeks used the names Phosphoros (meaning "light-bringer"; alternately Heosphoros, meaning "dawn-bringer") for the morning star, and Hesperus (meaning "Western one") for the evening star. Though by the Roman era they were recognized as one celestial object, known as "the star of Venus", the traditional two Greek names continued to be used, though usually translated to Latin as Lucifer and Hesperus.

Venus was considered the most important celestial body observed by the Maya, who called it Chac ek, or Noh Ek', "the Great Star".

Modern fiction

With the invention of the telescope, the idea that Venus was a physical world and possible destination began to take form.

The impenetrable Venusian cloud cover gave science fiction

writers free rein to speculate on conditions at its surface; all the

more so when early observations showed that not only was it similar in

size to Earth, it possessed a substantial atmosphere. Closer to the Sun

than Earth, the planet was frequently depicted as warmer, but still habitable by humans. The genre

reached its peak between the 1930s and 1950s, at a time when science

had revealed some aspects of Venus, but not yet the harsh reality of its

surface conditions. Findings from the first missions to Venus showed

the reality to be quite different, and brought this particular genre to

an end.

As scientific knowledge of Venus advanced, so science fiction authors

tried to keep pace, particularly by conjecturing human attempts to terraform Venus.

Symbol

The astronomical symbol for Venus is the same as that used in biology for the female sex: a circle with a small cross beneath. The Venus symbol also represents femininity, and in Western alchemy stood for the metal copper.

Polished copper has been used for mirrors from antiquity, and the

symbol for Venus has sometimes been understood to stand for the mirror

of the goddess.

Habitability

The speculation of the existence of life on Venus decreased

significantly since the early 1960s, when spacecraft began studying

Venus and it became clear that the conditions on Venus are extreme

compared to those on Earth.

The fact that Venus is located closer to the Sun than Earth,

raising temperatures on the surface to nearly 735 K (462 °C; 863 °F),

the atmospheric pressure is ninety times that of Earth, and the extreme

impact of the greenhouse effect, make water-based life as we know it unlikely. A few scientists have speculated that thermoacidophilic extremophile microorganisms might exist in the lower-temperature, acidic upper layers of the Venusian atmosphere.

The atmospheric pressure and temperature fifty kilometres above the

surface are similar to those at Earth's surface. This has led to

proposals to use aerostats (lighter-than-air balloons) for initial exploration and ultimately for permanent "floating cities" in the Venusian atmosphere. Among the many engineering challenges are the dangerous amounts of sulfuric acid at these heights.