Edwin Hubble

| |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

Edwin Powell Hubble

November 20, 1889

Marshfield, Missouri, U.S.

|

| Died | September 28, 1953 (aged 63)

San Marino, California, U.S.

|

| Residence | United States |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | University of Chicago The Queen's College, Oxford |

| Known for | Hubble sequence |

| Spouse(s) | Grace Burke Sr. |

| Awards | Newcomb Cleveland Prize 1924 Barnard Medal for Meritorious Service to Science 1935 Bruce Medal 1938 Franklin Medal 1939 Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society 1940 Legion of Merit 1946 |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Astronomy |

| Institutions | University of Chicago Mount Wilson Observatory |

| Influenced | Allan Sandage |

| Signature | |

Edwin Powell Hubble (November 20, 1889 – September 28, 1953) was an American astronomer. He played a crucial role in establishing the fields of extragalactic astronomy and observational cosmology and is regarded as one of the most important astronomers of all time.

Hubble discovered that many objects previously thought to be clouds of dust and gas and classified as "nebulae" were actually galaxies beyond the Milky Way. He used the strong direct relationship between a classical Cepheid variable's luminosity and pulsation period (discovered in 1908 by Henrietta Swan Leavitt) for scaling galactic and extragalactic distances.

Hubble provided evidence that the recessional velocity of a galaxy increases with its distance from the earth, a property now known as "Hubble's law", despite the fact that it had been both proposed and demonstrated observationally two years earlier by Georges Lemaître. Hubble-Lemaître's Law implies that the universe is expanding. A decade before, the American astronomer Vesto Slipher had provided the first evidence that the light from many of these nebulae was strongly red-shifted, indicative of high recession velocities.

Hubble's name is most widely recognized for the Hubble Space Telescope which was named in his honor, with a model prominently displayed in his hometown of Marshfield, Missouri.

Biography

Edwin Hubble was born to Virginia Lee Hubble (née James) (1864–1934) and John Powell Hubble, an insurance executive, in Marshfield, Missouri, and moved to Wheaton, Illinois, in 1900.

In his younger days, he was noted more for his athletic prowess than

his intellectual abilities, although he did earn good grades in every

subject except for spelling. Edwin was a gifted athlete, playing

baseball, football, basketball, and running track in both high school

and college. He played a variety of positions on the basketball court

from center to shooting guard. In fact, Hubble even led the University

of Chicago's basketball team to their first conference title in 1907. He won seven first places and a third place in a single high school track and field meet in 1906.

His studies at the University of Chicago were concentrated on law, which led to a bachelor of science degree in 1910. Hubble also became a member of the Kappa Sigma Fraternity. He spent the three years at The Queen's College, Oxford after earning his bachelor's as one of the university's first Rhodes Scholars, initially studying jurisprudence instead of science (as a promise to his dying father), and later added literature and Spanish, and earning his master's degree.

In 1909, Hubble's father moved his family from Chicago to Shelbyville, Kentucky, so that the family could live in a small town, ultimately settling in nearby Louisville.

His father died in the winter of 1913, while Edwin was still in

England, and in the summer of 1913, Edwin returned to care for his

mother, two sisters, and younger brother, as did his brother William.

The family moved once more to Everett Avenue, in Louisville's Highlands

neighborhood, to accommodate Edwin and William.

Hubble was also a dutiful son, who despite his intense interest

in astronomy since boyhood, acquiesced to his father's request to study

law, first at the University of Chicago and later at Oxford, though he

managed to take a few math and science courses. After the death of his

father in 1913, Edwin returned to the Midwest from Oxford but did not

have the motivation to practice law. Instead, he proceeded to teach

Spanish, physics and mathematics at New Albany High School in New Albany, Indiana,

where he also coached the boys' basketball team. After a year of

high-school teaching, he entered graduate school with the help of his

former professor from the University of Chicago to study astronomy at the university's Yerkes Observatory, where he received his Ph.D. in 1917. His dissertation was titled "Photographic Investigations of Faint Nebulae".

In Yerkes, he had access to one of the most powerful telescopes in the

world at the time, which had an innovative 24 inch (61 cm) reflector.

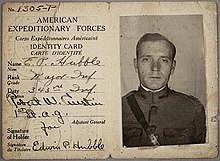

Hubble's identity card in the American Expeditionary Forces.

After the United States declared war on Germany in 1917, Hubble rushed to complete his Ph.D. dissertation so he could join the military. Hubble volunteered for the United States Army and was assigned to the newly created 86th Division, where he served in 2nd Battalion, 343 Infantry Regiment. He rose to the rank of lieutenant colonel, and was found fit for overseas duty on July 9, 1918, but the 86th Division never saw combat. After the end of World War I, Hubble spent a year in Cambridge, where he renewed his studies of astronomy. In 1919, Hubble was offered a staff position at the Carnegie Institution for Science's Mount Wilson Observatory, near Pasadena, California, by George Ellery Hale,

the founder and director of the observatory. Hubble remained on staff

at Mount Wilson until his death in 1953. Shortly before his death,

Hubble became the first astronomer to use the newly completed giant

200-inch (5.1 m) reflector Hale Telescope at the Palomar Observatory near San Diego, California.

Hubble also worked as a civilian for U.S. Army at Aberdeen Proving Ground in Maryland during World War II as the Chief of the External Ballistics Branch of the Ballistics Research Laboratory during which he directed a large volume of research in exterior ballistics

which increased the effective firepower of bombs and projectiles. His

work was facilitated by his personal development of several items of

equipment for the instrumentation used in exterior ballistics, the most

outstanding development being the high-speed clock camera, which made

possible the study of the characteristics of bombs and low-velocity

projectiles in flight. The results of his studies were credited with

greatly improving design, performance, and military effectiveness of

bombs and rockets. For his work there, he received the Legion of Merit award.

Hubble was raised as a Christian but some of his later statements suggest uncertainty.

Hubble married Mrs. Grace Lillian (Burke) Leib (1889–1980),

daughter of John Patrick and Luella (Kepford) Burke, on February 26,

1924.

Hubble had a heart attack in July 1949 while on vacation in Colorado. He was taken care of by his wife and continued on a modified diet and work schedule. He died of cerebral thrombosis (a spontaneous blood clot in his brain) on September 28, 1953, in San Marino, California. No funeral was held for him, and his wife never revealed his burial site.

Discoveries

Universe goes beyond the Milky Way galaxy

The 100-inch Hooker telescope at Mount Wilson Observatory that Hubble used to measure galaxy distances and a value for the rate of expansion of the universe.

Edwin Hubble's arrival at Mount Wilson Observatory, California in

1919 coincided roughly with the completion of the 100-inch (2.5 m) Hooker Telescope, then the world's largest. At that time, the prevailing view of the cosmos was that the universe consisted entirely of the Milky Way Galaxy. Using the Hooker Telescope at Mt. Wilson, Hubble identified Cepheid variables (a kind of star that is used as a means to determine the distance from the galaxy) in several spiral nebulae, including the Andromeda Nebula and Triangulum.

His observations, made in 1924, proved conclusively that these nebulae

were much too distant to be part of the Milky Way and were, in fact,

entire galaxies outside our own, suspected by researchers at least as

early as 1755 when Immanuel Kant's

General History of Nature and Theory of the Heavens appeared. This idea

had been opposed by many in the astronomy establishment of the time, in

particular by Harvard University-based Harlow Shapley. Despite the opposition, Hubble, then a thirty-five-year-old scientist, had his findings first published in The New York Times on November 23, 1924, then presented them to other astronomers at the January 1, 1925 meeting of the American Astronomical Society. Hubble's results for Andromeda were not formally published in a peer-reviewed scientific journal until 1929.

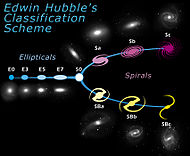

Hubble's classification scheme

Hubble's findings fundamentally changed the scientific view of the

universe. Supporters state that Hubble's discovery of nebulae outside of

our galaxy helped pave the way for future astronomers.

Although some of his more renowned colleagues simply scoffed at his

results, Hubble ended up publishing his findings on nebulae. This

published work earned him an award titled the American Association Prize

and five hundred dollars from Burton E. Livingston of the Committee on

Awards.

Hubble also devised the most commonly used system for classifying galaxies,

grouping them according to their appearance in photographic images. He

arranged the different groups of galaxies in what became known as the Hubble sequence.

Redshift increases with distance

Hubble

went on to estimate the distances to 24 extra-galactic nebulae, using a

variety of methods. In 1929 Hubble examined the relation between these

distances and their radial velocities as determined from their redshifts.

His estimated distances are now known to all be too small, by up to a

factor of about 7. This was due to factors such as the fact that there

are two kinds of Cepheid variables or confusing bright gas clouds with

bright stars.

However, his distances were more or less proportional to the true

distances, and combining his distances with measurements of the

redshifts of the galaxies by Vesto Slipher, and by his assistant Milton L. Humason,

he found a roughly linear relation between the distances of the

galaxies and their radial velocities (corrected for solar motion), a discovery that later became known as Hubble's law.

This meant, the greater the distance between any two galaxies,

the greater their relative speed of separation. If interpreted that way,

Hubble's measurements on 46 galaxies lead to a value for the Hubble Constant

of 500 km/s/Mpc, which is much higher than the currently accepted value

of 70 km/s/Mpc due to errors in their distance calibrations.

Yet the reason for the redshift remained unclear. Georges Lemaître, a Belgian Catholic priest and physicist, predicted on theoretical grounds based on Einstein's equations for general relativity the redshift-distance relation, and published observational support for it, two years before the discovery of Hubble's law.

However, many cosmologists and astronomers (including Hubble himself)

failed to recognize the work of Lemaître; Hubble remained doubtful about

Lemaître's interpretation for his entire life.

Although he used the term "velocities" in his paper (and "apparent

radial velocities" in the introduction), he later expressed doubt about

interpreting these as real velocities. In 1931 he wrote a letter to the

Dutch cosmologist Willem de Sitter expressing his opinion on the theoretical interpretation of the redshift-distance relation:

Mr. Humason and I are both deeply sensible of your gracious appreciation of the papers on velocities and distances of nebulae. We use the term 'apparent' velocities to emphasize the empirical features of the correlation. The interpretation, we feel, should be left to you and the very few others who are competent to discuss the matter with authority.

Today, the "apparent velocities" in question are usually thought of as an increase in proper distance that occurs due to the expansion of the universe. Light traveling through an expanding metric will experience a Hubble-type redshift, a mechanism somewhat different from the Doppler effect (although the two mechanisms become equivalent descriptions related by a coordinate transformation for nearby galaxies).

In the 1930s, Hubble was involved in determining the distribution of galaxies and spatial curvature. These data seemed to indicate that the universe was flat and homogeneous, but there was a deviation from flatness at large redshifts. According to Allan Sandage,

Hubble believed that his count data gave a more reasonable result concerning spatial curvature if the redshift correction was made assuming no recession. To the very end of his writings he maintained this position, favouring (or at the very least keeping open) the model where no true expansion exists, and therefore that the redshift "represents a hitherto unrecognized principle of nature.

There were methodological problems with Hubble's survey technique

that showed a deviation from flatness at large redshifts. In particular,

the technique did not account for changes in luminosity of galaxies due

to galaxy evolution.

Earlier, in 1917, Albert Einstein

had found that his newly developed theory of general relativity

indicated that the universe must be either expanding or contracting.

Unable to believe what his own equations were telling him, Einstein

introduced a cosmological constant (a "fudge factor")

to the equations to avoid this "problem". When Einstein learned of

Hubble's redshifts, he immediately realized that the expansion predicted

by general relativity must be real, and in later life he said that

changing his equations was "the biggest blunder of [his] life." In fact,

Einstein apparently once visited Hubble and tried to convince him that

the universe was expanding.

Hubble also discovered the asteroid 1373 Cincinnati on August 30, 1935. In 1936 he wrote The Observational Approach to Cosmology and The Realm of the Nebulae which explained his approaches to extra-galactic astronomy and his view of the subject's history.

In December 1941, Hubble reported to the American Association for the Advancement of Science

that results from a six-year survey with the Mt. Wilson telescope did

not support the expanding universe theory. According to an LA Times

article reporting on Hubble's remarks, "The nebulae could not be

uniformly distributed, as the telescope shows they are, and still fit

the explosion idea. Explanations which try to get around what the great

telescope sees, he said, fail to stand up. The explosion for example

would have had to start long after the earth was created, and possibly

even after the first life appeared here." (Hubble's estimate of what we now call the Hubble constant would put the Big Bang only 2000 million years ago.)

Accusations concerning Lemaître's priority

In 2011 the journal Nature reported claims that Hubble had played a role in the redaction

of key parts of the translation of Lemaître's 1927 paper, which stated

what is now called Hubble's Law and also gave observational evidence for

it. Historians quoted in the article were skeptical that the

redactions were part of a campaign to ensure Hubble retained priority.

However, the observational astronomer Sidney van den Bergh published a paper suggesting that while the omissions may have been made by a translator, they may still have been deliberate.

In November 2011, the astronomer Mario Livio reported in Nature

that documents in the Lemaître archive demonstrated that the redaction

had indeed been carried out by Lemaître himself, who apparently saw

little point in including scientific content which had already been

reported by Hubble.

No Nobel Prize

At the time, the Nobel Prize in Physics

did not recognize work done in astronomy. Hubble spent much of the

later part of his career attempting to have astronomy considered an area

of physics, instead of being its own science. He did this largely so

that astronomers—including himself—could be recognized by the Nobel Prize Committee for their valuable contributions to astrophysics.

This campaign was unsuccessful in Hubble's lifetime, but shortly after

his death, the Nobel Prize Committee decided that astronomical work

would be eligible for the physics prize. However, the prize is not one that can be awarded posthumously.

Stamp

On March 6, 2008, the United States Postal Service released a 41-cent stamp honoring Hubble on a sheet titled "American Scientists" designed by artist Victor Stabin. His citation reads:

Often called a "pioneer of the distant stars," astronomer Edwin Hubble (1889–1953) played a pivotal role in deciphering the vast and complex nature of the universe. His meticulous studies of spiral nebulae proved the existence of galaxies other than our own Milky Way. Had he not died suddenly in 1953, Hubble would have won that year's Nobel Prize in Physics.

(Note that the assertion that he would have won the Nobel Prize in

1953 is likely false, although he was nominated for the prize that

year.)

The other scientists on the "American Scientists" sheet include Gerty Cori, biochemist; Linus Pauling, chemist, and John Bardeen, physicist.

Honors

Awards

- Newcomb Cleveland Prize in 1924;

- Bruce Medal in 1938;

- Franklin Medal in 1939;

- Gold Medal of the Royal Astronomical Society in 1940;

- Legion of Merit for outstanding contribution to ballistics research in 1946;

Namesakes

- Asteroid 2069 Hubble;

- The crater Hubble on the Moon;

- Orbiting Hubble Space Telescope;

- Edwin P. Hubble Planetarium, located in the Edward R. Murrow High School, Brooklyn, NY.;

- Edwin Hubble Highway, the stretch of Interstate 44 passing through his birthplace of Marshfield, Missouri;

- Hubble Middle School, a public school in Wheaton, Illinois where he lived from 11 years old and up.

Other notable appearances

- Hall of Famous Missourians 2003

- 2008 "American Scientists" US stamp series, $0.41.

- 2017 Indiana Basketball Hall of Fame

In popular culture

The play Creation's Birthday, written by Cornell physicist Hasan Padamsee, tells Hubble's life story.

A famous quote by Edwin Hubble goes: "Equipped with his five

senses man explores the universe around him and calls the adventure

Science".

In the popular documentary Cosmos: A Personal Voyage by astronomer Carl Sagan, Hubble's life and work are portrayed on screen in episode 10: The Edge of Forever.

His work on Red Shift was immortalized in a limerick by Alexander Rolfe:

Thanks to Edwin P. HubbleOur static cosmology was in serious trouble--When we saw a wavelengthOf such tiny strength,It proved the universe was an expanding bubble.