Lithium floating in oil

| ||||||||||||||||

| Lithium | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pronunciation | /ˈlɪθiəm/ | |||||||||||||||

| Appearance | silvery-white | |||||||||||||||

| Standard atomic weight Ar, std(Li) | [6.938, 6.997] conventional: 6.94 | |||||||||||||||

| Lithium in the periodic table | ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

| Atomic number (Z) | 3 | |||||||||||||||

| Group | group 1 (alkali metals) | |||||||||||||||

| Period | period 2 | |||||||||||||||

| Block | s-block | |||||||||||||||

| Element category | alkali metal | |||||||||||||||

| Electron configuration | [He] 2s1 | |||||||||||||||

Electrons per shell

| 2, 1 | |||||||||||||||

| Physical properties | ||||||||||||||||

| Phase at STP | solid | |||||||||||||||

| Melting point | 453.65 K (180.50 °C, 356.90 °F) | |||||||||||||||

| Boiling point | 1603 K (1330 °C, 2426 °F) | |||||||||||||||

| Density (near r.t.) | 0.534 g/cm3 | |||||||||||||||

| when liquid (at m.p.) | 0.512 g/cm3 | |||||||||||||||

| Critical point | 3220 K, 67 MPa (extrapolated) | |||||||||||||||

| Heat of fusion | 3.00 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||

| Heat of vaporization | 136 kJ/mol | |||||||||||||||

| Molar heat capacity | 24.860 J/(mol·K) | |||||||||||||||

Vapor pressure

| ||||||||||||||||

| Atomic properties | ||||||||||||||||

| Oxidation states | +1 (a strongly basic oxide) | |||||||||||||||

| Electronegativity | Pauling scale: 0.98 | |||||||||||||||

| Ionization energies |

| |||||||||||||||

| Atomic radius | empirical: 152 pm | |||||||||||||||

| Covalent radius | 128±7 pm | |||||||||||||||

| Van der Waals radius | 182 pm | |||||||||||||||

| Spectral lines of lithium | ||||||||||||||||

| Other properties | ||||||||||||||||

| Natural occurrence | primordial | |||||||||||||||

| Crystal structure | body-centered cubic (bcc) | |||||||||||||||

| Speed of sound thin rod | 6000 m/s (at 20 °C) | |||||||||||||||

| Thermal expansion | 46 µm/(m·K) (at 25 °C) | |||||||||||||||

| Thermal conductivity | 84.8 W/(m·K) | |||||||||||||||

| Electrical resistivity | 92.8 nΩ·m (at 20 °C) | |||||||||||||||

| Magnetic ordering | paramagnetic | |||||||||||||||

| Magnetic susceptibility | +14.2·10−6 cm3/mol (298 K) | |||||||||||||||

| Young's modulus | 4.9 GPa | |||||||||||||||

| Shear modulus | 4.2 GPa | |||||||||||||||

| Bulk modulus | 11 GPa | |||||||||||||||

| Mohs hardness | 0.6 | |||||||||||||||

| Brinell hardness | 5 MPa | |||||||||||||||

| CAS Number | 7439-93-2 | |||||||||||||||

| History | ||||||||||||||||

| Discovery | Johan August Arfwedson (1817) | |||||||||||||||

| First isolation | William Thomas Brande (1821) | |||||||||||||||

| Main isotopes of lithium | ||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||

| 6Li content may be as low as 3.75% in natural samples. 7Li would therefore have a content of up to 96.25%. | ||||||||||||||||

Lithium (from Greek: λίθος, translit. lithos, lit. 'stone') is a chemical element with symbol Li and atomic number 3. It is a soft, silvery-white alkali metal. Under standard conditions, it is the lightest metal and the lightest solid element. Like all alkali metals, lithium is highly reactive and flammable, and is stored in mineral oil. When cut, it exhibits a metallic luster, but moist air corrodes it quickly to a dull silvery gray, then black tarnish. It never occurs freely in nature, but only in (usually ionic) compounds, such as pegmatitic minerals, which were once the main source of lithium. Due to its solubility as an ion, it is present in ocean water and is commonly obtained from brines. Lithium metal is isolated electrolytically from a mixture of lithium chloride and potassium chloride.

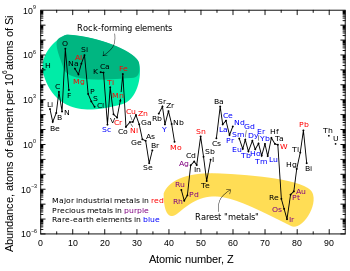

The nucleus of the lithium atom verges on instability, since the two stable lithium isotopes found in nature have among the lowest binding energies per nucleon of all stable nuclides. Because of its relative nuclear instability, lithium is less common in the solar system than 25 of the first 32 chemical elements even though its nuclei are very light: it is an exception to the trend that heavier nuclei are less common. For related reasons, lithium has important uses in nuclear physics. The transmutation of lithium atoms to helium in 1932 was the first fully man-made nuclear reaction, and lithium deuteride serves as a fusion fuel in staged thermonuclear weapons.

Lithium and its compounds have several industrial applications, including heat-resistant glass and ceramics, lithium grease lubricants, flux additives for iron, steel and aluminium production, lithium batteries, and lithium-ion batteries. These uses consume more than three quarters of lithium production.

Lithium is present in biological systems in trace amounts; its functions are uncertain. Lithium salts have proven to be useful as a mood-stabilizing drug in the treatment of bipolar disorder in humans.

Properties

Atomic and physical

Lithium ingots with a thin layer of black nitride tarnish

Like the other alkali metals, lithium has a single valence electron that is easily given up to form a cation.

Because of this, lithium is a good conductor of heat and electricity as

well as a highly reactive element, though it is the least reactive of

the alkali metals. Lithium's low reactivity is due to the proximity of

its valence electron to its nucleus (the remaining two electrons are in the 1s orbital, much lower in energy, and do not participate in chemical bonds).

Lithium metal is soft enough to be cut with a knife. When cut, it

possesses a silvery-white color that quickly changes to gray as it

oxidizes to lithium oxide. While it has one of the lowest melting points among all metals (180 °C), it has the highest melting and boiling points of the alkali metals.

Lithium has a very low density (0.534 g/cm3),

comparable with pine wood. It is the least dense of all elements that

are solids at room temperature; the next lightest solid element

(potassium, at 0.862 g/cm3) is more than 60% denser. Furthermore, apart from helium and hydrogen, it is less dense than any liquid element, being only two thirds as dense as liquid nitrogen (0.808 g/cm3).

Lithium can float on the lightest hydrocarbon oils and is one of only

three metals that can float on water, the other two being sodium and potassium.

Lithium floating in oil

Lithium's coefficient of thermal expansion is twice that of aluminium and almost four times that of iron. Lithium is superconductive below 400 μK at standard pressure and at higher temperatures (more than 9 K) at very high pressures (g.t. 20 GPa). At temperatures below 70 K, lithium, like sodium, undergoes diffusionless phase change transformations. At 4.2 K it has a rhombohedral crystal system (with a nine-layer repeat spacing); at higher temperatures it transforms to face-centered cubic and then body-centered cubic. At liquid-helium temperatures (4 K) the rhombohedral structure is prevalent. Multiple allotropic forms have been identified for lithium at high pressures.

Lithium has a mass specific heat capacity of 3.58 kilojoules per kilogram-kelvin, the highest of all solids. Because of this, lithium metal is often used in coolants for heat transfer applications.

Chemistry and compounds

Lithium reacts with water easily, but with noticeably less vigor than other alkali metals. The reaction forms hydrogen gas and lithium hydroxide in aqueous solution. Because of its reactivity with water, lithium is usually stored in a hydrocarbon sealant, often petroleum jelly. Though the heavier alkali metals can be stored in more dense substances, such as mineral oil, lithium is not dense enough to be fully submerged in these liquids. In moist air, lithium rapidly tarnishes to form a black coating of lithium hydroxide (LiOH and LiOH·H2O), lithium nitride (Li3N) and lithium carbonate (Li2CO3, the result of a secondary reaction between LiOH and CO2).

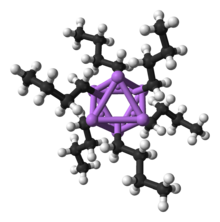

Hexameric structure of the n-butyllithium fragment in a crystal

When placed over a flame, lithium compounds give off a striking

crimson color, but when it burns strongly the flame becomes a brilliant

silver. Lithium will ignite and burn in oxygen when exposed to water or

water vapors. Lithium is flammable, and it is potentially explosive when exposed to air and especially to water, though less so than the other alkali metals.

The lithium-water reaction at normal temperatures is brisk but

nonviolent because the hydrogen produced does not ignite on its own. As

with all alkali metals, lithium fires are difficult to extinguish,

requiring dry powder fire extinguishers (Class D type). Lithium is one of the few metals that react with nitrogen under normal conditions.

Lithium has a diagonal relationship with magnesium, an element of similar atomic and ionic radius. Chemical resemblances between the two metals include the formation of a nitride by reaction with N2, the formation of an oxide (Li

2O) and peroxide (Li

2O

2) when burnt in O2, salts with similar solubilities, and thermal instability of the carbonates and nitrides. The metal reacts with hydrogen gas at high temperatures to produce lithium hydride (LiH).

2O) and peroxide (Li

2O

2) when burnt in O2, salts with similar solubilities, and thermal instability of the carbonates and nitrides. The metal reacts with hydrogen gas at high temperatures to produce lithium hydride (LiH).

Other known binary compounds include halides (LiF, LiCl, LiBr, LiI), sulfide (Li

2S), superoxide (LiO

2), and carbide (Li

2C

2). Many other inorganic compounds are known in which lithium combines with anions to form salts: borates, amides, carbonate, nitrate, or borohydride (LiBH

4). Lithium aluminium hydride (LiAlH

4) is commonly used as a reducing agent in organic synthesis.

2S), superoxide (LiO

2), and carbide (Li

2C

2). Many other inorganic compounds are known in which lithium combines with anions to form salts: borates, amides, carbonate, nitrate, or borohydride (LiBH

4). Lithium aluminium hydride (LiAlH

4) is commonly used as a reducing agent in organic synthesis.

LiHe, a very weakly interacting van der Waals compound, has been detected at very low temperatures.

Organic chemistry

Multiple organolithium reagents are known in which there is a direct bond between carbon and lithium atoms, effectively creating a carbanion. These are extremely powerful bases and nucleophiles.

They have also been applied in asymmetric synthesis in the

pharmaceutical industry. In many of these organolithium compounds, the

lithium ions tend to aggregate into high-symmetry clusters by

themselves, which is relatively common for alkali cations.

For laboratory organic synthesis, many organolithium reagents are

commercially available in solution form. These reagents are highly

reactive, and are sometimes pyrophoric.

Isotopes

Naturally occurring lithium is composed of two stable isotopes, 6Li and 7Li, the latter being the more abundant (92.5% natural abundance). Both natural isotopes have anomalously low nuclear binding energy per nucleon (compared to the neighboring elements on the periodic table, helium and beryllium); lithium is the only low numbered element that can produce net energy through nuclear fission. The two lithium nuclei have lower binding energies per nucleon than any other stable nuclides other than deuterium and helium-3.

As a result of this, though very light in atomic weight, lithium is

less common in the Solar System than 25 of the first 32 chemical

elements. Seven radioisotopes have been characterized, the most stable being 8Li with a half-life of 838 ms and 9Li with a half-life of 178 ms. All of the remaining radioactive isotopes have half-lives that are shorter than 8.6 ms. The shortest-lived isotope of lithium is 4Li, which decays through proton emission and has a half-life of 7.6 × 10−23 s.

7Li is one of the primordial elements (or, more properly, primordial nuclides) produced in Big Bang nucleosynthesis. A small amount of both 6Li and 7Li are produced in stars, but are thought to be "burned" as fast as produced. Additional small amounts of lithium of both 6Li and 7Li may be generated from solar wind, cosmic rays hitting heavier atoms, and from early solar system 7Be and 10Be radioactive decay. While lithium is created in stars during stellar nucleosynthesis, it is further burned. 7Li can also be generated in carbon stars.

Lithium isotopes fractionate substantially during a wide variety of natural processes, including mineral formation (chemical precipitation), metabolism, and ion exchange. Lithium ions substitute for magnesium and iron in octahedral sites in clay minerals, where 6Li is preferred to 7Li, resulting in enrichment of the light isotope in processes of hyperfiltration and rock alteration. The exotic 11Li is known to exhibit a nuclear halo. The process known as laser isotope separation can be used to separate lithium isotopes, in particular 7Li from 6Li.

Nuclear weapons manufacture and other nuclear physics

applications are a major source of artificial lithium fractionation,

with the light isotope 6Li being retained by industry and military stockpiles to such an extent that it has caused slight but measurable change in the 6Li to 7Li ratios in natural sources, such as rivers. This has led to unusual uncertainty in the standardized atomic weight

of lithium, since this quantity depends on the natural abundance ratios

of these naturally-occurring stable lithium isotopes, as they are

available in commercial lithium mineral sources.

Both stable isotopes of lithium can be laser cooled and were used to produce the first quantum degenerate Bose-Fermi mixture.

Occurrence

Astronomical

Though it was synthesized in the Big Bang,

lithium (together with beryllium and boron), is markedly less abundant

in the universe than other elements. This is a result of the

comparatively low stellar temperatures necessary to destroy lithium,

along with a lack of common processes to produce it.

According to modern cosmological theory, lithium—in both stable

isotopes (lithium-6 and lithium-7)—was one of the three elements synthesized in the Big Bang. Though the amount of lithium generated in Big Bang nucleosynthesis is dependent upon the number of photons per baryon,

for accepted values the lithium abundance can be calculated, and there

is a "cosmological lithium discrepancy" in the universe: older stars

seem to have less lithium than they should, and some younger stars have

much more.

The lack of lithium in older stars is apparently caused by the "mixing"

of lithium into the interior of stars, where it is destroyed, while lithium is produced in younger stars. Though it transmutes into two atoms of helium due to collision with a proton

at temperatures above 2.4 million degrees Celsius (most stars easily

attain this temperature in their interiors), lithium is more abundant

than current computations would predict in later-generation stars.

Nova Centauri 2013 is the first in which evidence of lithium has been found.

Lithium is also found in brown dwarf

substellar objects and certain anomalous orange stars. Because lithium

is present in cooler, less-massive brown dwarfs, but is destroyed in

hotter red dwarf

stars, its presence in the stars' spectra can be used in the "lithium

test" to differentiate the two, as both are smaller than the Sun. Certain orange stars can also contain a high concentration of lithium.

Those orange stars found to have a higher than usual concentration of

lithium (such as Centaurus X-4)

orbit massive objects—neutron stars or black holes—whose gravity

evidently pulls heavier lithium to the surface of a hydrogen-helium

star, causing more lithium to be observed.

Terrestrial

Although lithium is widely distributed on Earth, it does not naturally occur in elemental form due to its high reactivity.

The total lithium content of seawater is very large and is estimated as

230 billion tonnes, where the element exists at a relatively constant

concentration of 0.14 to 0.25 parts per million (ppm), or 25 micromolar; higher concentrations approaching 7 ppm are found near hydrothermal vents.

Estimates for the Earth's crustal content range from 20 to 70 ppm by weight. In keeping with its name, lithium forms a minor part of igneous rocks, with the largest concentrations in granites. Granitic pegmatites also provide the greatest abundance of lithium-containing minerals, with spodumene and petalite being the most commercially viable sources. Another significant mineral of lithium is lepidolite which is now an obsolete name for a series formed by polylithionite and trilithionite. A newer source for lithium is hectorite clay, the only active development of which is through the Western Lithium Corporation in the United States. At 20 mg lithium per kg of Earth's crust, lithium is the 25th most abundant element.

According to the Handbook of Lithium and Natural Calcium,

"Lithium is a comparatively rare element, although it is found in many

rocks and some brines, but always in very low concentrations. There are a

fairly large number of both lithium mineral and brine deposits but only

comparatively few of them are of actual or potential commercial value.

Many are very small, others are too low in grade."

The US Geological Survey estimates that in 2010, Chile had the largest reserves by far (7.5 million tonnes) and the highest annual production (8,800 tonnes). One of the largest reserve bases of lithium is in the Salar de Uyuni area of Bolivia, which has 5.4 million tonnes. Other major suppliers include Australia, Argentina and China. As of 2015, the Czech Geological Survey considered the entire Ore Mountains in the Czech Republic as lithium province. Five deposits are registered, one near Cínovec is considered as a potentially economical deposit, with 160 000 tonnes of lithium.

In June 2010, The New York Times reported that American geologists were conducting ground surveys on dry salt lakes

in western Afghanistan believing that large deposits of lithium are

located there. "Pentagon officials said that their initial analysis at

one location in Ghazni Province

showed the potential for lithium deposits as large as those of Bolivia,

which now has the world's largest known lithium reserves."

These estimates are "based principally on old data, which was gathered

mainly by the Soviets during their occupation of Afghanistan from

1979–1989". Stephen Peters, the head of the USGS's Afghanistan Minerals

Project, said that he was unaware of USGS involvement in any new

surveying for minerals in Afghanistan in the past two years. 'We are not

aware of any discoveries of lithium,' he said."

Lithia ("lithium brine") is associated with tin mining areas in Cornwall,

England and an evaluation project from 400-meter deep test boreholes is

under consideration. If successful the hot brines will also provide geothermal energy to power the lithium extraction and refining process.

Biological

Lithium is found in trace amount in numerous plants, plankton, and

invertebrates, at concentrations of 69 to 5,760 parts per billion (ppb).

In vertebrates the concentration is slightly lower, and nearly all

vertebrate tissue and body fluids contain lithium ranging from 21 to 763

ppb. Marine organisms tend to bioaccumulate lithium more than terrestrial organisms. Whether lithium has a physiological role in any of these organisms is unknown.

History

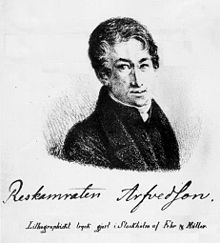

Johan August Arfwedson is credited with the discovery of lithium in 1817

Petalite (LiAlSi4O10) was discovered in 1800 by the Brazilian chemist and statesman José Bonifácio de Andrada e Silva in a mine on the island of Utö, Sweden. However, it was not until 1817 that Johan August Arfwedson, then working in the laboratory of the chemist Jöns Jakob Berzelius, detected the presence of a new element while analyzing petalite ore. This element formed compounds similar to those of sodium and potassium, though its carbonate and hydroxide were less soluble in water and less alkaline. Berzelius gave the alkaline material the name "lithion/lithina", from the Greek word λιθoς (transliterated as lithos,

meaning "stone"), to reflect its discovery in a solid mineral, as

opposed to potassium, which had been discovered in plant ashes, and

sodium, which was known partly for its high abundance in animal blood.

He named the metal inside the material "lithium".

Arfwedson later showed that this same element was present in the minerals spodumene and lepidolite. In 1818, Christian Gmelin was the first to observe that lithium salts give a bright red color to flame. However, both Arfwedson and Gmelin tried and failed to isolate the pure element from its salts. It was not isolated until 1821, when William Thomas Brande obtained it by electrolysis of lithium oxide, a process that had previously been employed by the chemist Sir Humphry Davy to isolate the alkali metals potassium and sodium. Brande also described some pure salts of lithium, such as the chloride, and, estimating that lithia (lithium oxide) contained about 55% metal, estimated the atomic weight of lithium to be around 9.8 g/mol (modern value ~6.94 g/mol). In 1855, larger quantities of lithium were produced through the electrolysis of lithium chloride by Robert Bunsen and Augustus Matthiessen. The discovery of this procedure led to commercial production of lithium in 1923 by the German company Metallgesellschaft AG, which performed an electrolysis of a liquid mixture of lithium chloride and potassium chloride.

The production and use of lithium underwent several drastic

changes in history. The first major application of lithium was in

high-temperature lithium greases for aircraft engines and similar applications in World War II

and shortly after. This use was supported by the fact that

lithium-based soaps have a higher melting point than other alkali soaps,

and are less corrosive than calcium based soaps. The small demand for

lithium soaps and lubricating greases was supported by several small

mining operations, mostly in the US.

The demand for lithium increased dramatically during the Cold War with the production of nuclear fusion weapons. Both lithium-6 and lithium-7 produce tritium

when irradiated by neutrons, and are thus useful for the production of

tritium by itself, as well as a form of solid fusion fuel used inside

hydrogen bombs in the form of lithium deuteride.

The US became the prime producer of lithium between the late 1950s and

the mid 1980s. At the end, the stockpile of lithium was roughly 42,000

tonnes of lithium hydroxide. The stockpiled lithium was depleted in

lithium-6 by 75%, which was enough to affect the measured atomic weight

of lithium in many standardized chemicals, and even the atomic weight

of lithium in some "natural sources" of lithium ion which had been

"contaminated" by lithium salts discharged from isotope separation

facilities, which had found its way into ground water.

Lithium was used to decrease the melting temperature of glass and to improve the melting behavior of aluminium oxide when using the Hall-Héroult process. These two uses dominated the market until the middle of the 1990s. After the end of the nuclear arms race, the demand for lithium decreased and the sale of department of energy stockpiles on the open market further reduced prices. In the mid 1990s, several companies started to extract lithium from brine

which proved to be a less expensive option than underground or open-pit

mining. Most of the mines closed or shifted their focus to other

materials because only the ore from zoned pegmatites could be mined for a

competitive price. For example, the US mines near Kings Mountain, North Carolina closed before the beginning of the 21st century.

The development of lithium ion batteries increased the demand for lithium and became the dominant use in 2007.

With the surge of lithium demand in batteries in the 2000s, new

companies have expanded brine extraction efforts to meet the rising

demand.

Production

Satellite images of the Salar del Hombre Muerto, Argentina (left), and Uyuni, Bolivia (right), salt flats that are rich in lithium. The lithium-rich brine is concentrated by pumping it into solar evaporation ponds (visible in the top image).

Lithium production has greatly increased since the end of World War II. The metal is separated from other elements in igneous minerals. The metal is produced through electrolysis from a mixture of fused 55% lithium chloride and 45% potassium chloride at about 450 °C.

As of 2015, most of the world's lithium production is in South

America, where lithium-containing brine is extracted from underground

pools and concentrated by solar evaporation. The standard extraction

technique is to evaporate water from brine. Each batch takes from 18 to

24 months.

In 1998, the price of lithium was about 95 USD/kg (or 43 USD/lb).

Reserves

Worldwide identified reserves in 2018 are estimated by the US Geological Survey (USGS) to be 16 million tonnes, though an accurate estimate of world lithium reserves is difficult.

One reason for this is that most lithium classification schemes are

developed for solid ore deposits, whereas brine is a fluid that is

problematic to treat with the same classification scheme due to varying

concentrations and pumping effects.

The world has been estimated to contain about 15 million tonnes of

lithium reserves, while 65 million tonnes of known resources are

reasonable. A total of 75% of everything can typically be found in the

ten largest deposits of the world.

Another study noted that 83% of the geological resources of lithium are

located in six brine, two pegmatite, and two sedimentary deposits.

The world’s top 3 lithium-producing countries from 2016, as

reported by the US Geological Survey are Australia, Chile and Argentina. The intersection of Chile, Bolivia, and Argentina make up the region known as the Lithium Triangle. The Lithium Triangle is known for its high quality salt flats including Bolivia's Salar de Uyuni, Chile's Salar de Atacama, and Argentina's Salar de Arizaro. The Lithium Triangle is believed to contain over 75% of existing known lithium reserves. Deposits are found in South America throughout the Andes

mountain chain. Chile is the leading producer, followed by Argentina.

Both countries recover lithium from brine pools. According to USGS,

Bolivia's Uyuni Desert has 5.4 million tonnes of lithium. Half the world's known reserves are located in Bolivia

along the central eastern slope of the Andes. In 2009, Bolivia

negotiated with Japanese, French, and Korean firms to begin extraction.

| Country | Production | Reserves | Resources |

|---|---|---|---|

| 5,500 | 2,000,000 | 9,800,000 | |

| 18,700 | 2,700,000 | 5,000,000 | |

| - | - | 50,000 | |

| - | - | 9,000,000 | |

| 200 | 48,000 | 180,000 | |

| 480 | 180,000 | 1,900,000 | |

| 14,100 | 7,500,000 | 8,400,000 | |

| - | - | 840,000 | |

| - | - | 1,000,000 | |

| - | - | 200,000 | |

| - | - | 180,000 | |

| 3,000 | 3,200,000 | 7,000,000 | |

| 400 | 60,000 | 100,000 | |

| - | - | 1,000,000 | |

| - | - | 1,000,000 | |

| - | - | 400,000 | |

| 870 | 35,000 | 6,800,000 | |

| 1,000 | 23,000 | 500,000 | |

| World total | 43,000 | 16,000,000 | 53,000,000+ |

In the US, lithium is recovered from brine pools in Nevada. A deposit discovered in 2013 in Wyoming's Rock Springs Uplift

is estimated to contain 228,000 tons. Additional deposits in the same

formation were estimated to be as much as 18 million tons.

Opinions differ about potential growth. A 2008 study concluded

that "realistically achievable lithium carbonate production will be

sufficient for only a small fraction of future PHEV and EV

global market requirements", that "demand from the portable electronics

sector will absorb much of the planned production increases in the next

decade", and that "mass production of lithium carbonate is not

environmentally sound, it will cause irreparable ecological damage to

ecosystems that should be protected and that LiIon propulsion is incompatible with the notion of the 'Green Car'".

According to a 2011 study by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory and the University of California, Berkeley,

the currently estimated reserve base of lithium should not be a

limiting factor for large-scale battery production for electric vehicles

because an estimated 1 billion 40 kWh Li-based batteries could be built with current reserves - about 10 kg of lithium per car. Another 2011 study at the University of Michigan and Ford Motor Company

found enough resources to support global demand until 2100, including

the lithium required for the potential widespread transportation use.

The study estimated global reserves at 39 million tons, and total demand

for lithium during the 90-year period annualized at 12–20 million tons,

depending on the scenarios regarding economic growth and recycling

rates.

On 9 June 2014, the Financialist stated that demand for

lithium was growing at more than 12% a year. According to Credit Suisse,

this rate exceeds projected availability by 25%. The publication

compared the 2014 lithium situation with oil, whereby "higher oil prices

spurred investment in expensive deepwater and oil sands production

techniques"; that is, the price of lithium will continue to rise until

more expensive production methods that can boost total output receive

the attention of investors.

On 16 July 2018 2.5 million tonnes of high-grade lithium

resources and 124 million pounds of uranium resources were found in the

Falchani hard rock deposit in the region Puno, Peru.

Pricing

After the 2007 financial crisis, major suppliers, such as Sociedad Química y Minera (SQM), dropped lithium carbonate pricing by 20%. Prices rose in 2012. A 2012 Business Week article outlined the oligopoly in the lithium space: "SQM, controlled by billionaire Julio Ponce, is the second-largest, followed by Rockwood, which is backed by Henry Kravis’s KKR & Co., and Philadelphia-based FMC", with Talison mentioned as the biggest producer.

Global consumption may jump to 300,000 metric tons a year by 2020 from

about 150,000 tons in 2012, to match the demand for lithium batteries

that has been growing at about 25% a year, outpacing the 4% to 5%

overall gain in lithium production.

Extraction

Analyses of the extraction of lithium from seawater, published in 1975

Lithium salts are extracted from water in mineral springs, brine

pools, and brine deposits. Brine excavation is probably the only

lithium extraction technology widely used today, as actual mining of

lithium ores is much more expensive and has been priced out of the

market.

Lithium is present in seawater, but commercially viable methods of extraction have yet to be developed.

Another potential source of lithium is the leachates of geothermal wells, which are carried to the surface. Recovery of lithium has been demonstrated in the field; the lithium is separated by simple filtration.

The process and environmental costs are primarily those of the

already-operating well; net environmental impacts may thus be positive.

Investment

Currently, there are a number of options available in the marketplace

to invest in the metal. While buying physical stock of lithium is

hardly possible, investors can buy shares of companies engaged in

lithium mining and producing. Also, investors can purchase a dedicated lithium ETF offering exposure to a group of commodity producers.

Applications

Estimates of global lithium uses in 2011 (picture) and 2015

Ceramics and glass (32%)

Batteries (35%)

Lubricating greases (9%)

Continuous casting (5%)

Air treatment (5%)

Polymers (4%)

Primary aluminum production (1%)

Pharmaceuticals (<1 span="">

Other (9%)

Ceramics and glass

Lithium oxide is widely used as a flux for processing silica, reducing the melting point and viscosity of the material and leading to glazes

with improved physical properties including low coefficients of thermal

expansion. Worldwide, this is one of the largest use for lithium

compounds. Glazes containing lithium oxides are used for ovenware. Lithium carbonate (Li2CO3) is generally used in this application because it converts to the oxide upon heating.

Electrical and electronics

Late in the 20th century, lithium became an important component of battery electrolytes and electrodes, because of its high electrode potential. Because of its low atomic mass, it has a high charge- and power-to-weight ratio. A typical lithium-ion battery can generate approximately 3 volts per cell, compared with 2.1 volts for lead-acid and 1.5 volts for zinc-carbon. Lithium-ion batteries, which are rechargeable and have a high energy density, differ from lithium batteries, which are disposable (primary) batteries with lithium or its compounds as the anode. Other rechargeable batteries that use lithium include the lithium-ion polymer battery, lithium iron phosphate battery, and the nanowire battery.

Lubricating greases

The third most common use of lithium is in greases. Lithium hydroxide is a strong base and, when heated with a fat, produces a soap made of lithium stearate. Lithium soap has the ability to thicken oils, and it is used to manufacture all-purpose, high-temperature lubricating greases.

Metallurgy

Lithium (e.g. as lithium carbonate) is used as an additive to continuous casting mould flux slags where it increases fluidity, a use which accounts for 5% of global lithium use (2011). Lithium compounds are also used as additives (fluxes) to foundry sand for iron casting to reduce veining.

Lithium (as lithium fluoride) is used as an additive to aluminium smelters (Hall–Héroult process), reducing melting temperature and increasing electrical resistance, a use which accounts for 3% of production (2011).

When used as a flux for welding or soldering, metallic lithium promotes the fusing of metals during the process and eliminates the forming of oxides by absorbing impurities. Alloys of the metal with aluminium, cadmium, copper and manganese are used to make high-performance aircraft parts.

Silicon nano-welding

Lithium has been found effective in assisting the perfection of

silicon nano-welds in electronic components for electric batteries and

other devices.

Other chemical and industrial uses

Lithium use in flares and pyrotechnics is due to its rose-red flame.

Pyrotechnics

Air purification

Lithium chloride and lithium bromide are hygroscopic and are used as desiccants for gas streams. Lithium hydroxide and lithium peroxide are the salts most used in confined areas, such as aboard spacecraft and submarines, for carbon dioxide removal and air purification. Lithium hydroxide absorbs carbon dioxide from the air by forming lithium carbonate, and is preferred over other alkaline hydroxides for its low weight.

Lithium peroxide (Li2O2) in presence of moisture not only reacts with carbon dioxide to form lithium carbonate, but also releases oxygen. The reaction is as follows:

- 2 Li2O2 + 2 CO2 → 2 Li2CO3 + O2.

Some of the aforementioned compounds, as well as lithium perchlorate, are used in oxygen candles that supply submarines with oxygen. These can also include small amounts of boron, magnesium, aluminum, silicon, titanium, manganese, and iron.

Optics

Lithium fluoride, artificially grown as crystal, is clear and transparent and often used in specialist optics for IR, UV and VUV (vacuum UV) applications. It has one of the lowest refractive indexes and the furthest transmission range in the deep UV of most common materials. Finely divided lithium fluoride powder has been used for thermoluminescent radiation dosimetry (TLD): when a sample of such is exposed to radiation, it accumulates crystal defects which, when heated, resolve via a release of bluish light whose intensity is proportional to the absorbed dose, thus allowing this to be quantified. Lithium fluoride is sometimes used in focal lenses of telescopes.

The high non-linearity of lithium niobate also makes it useful in non-linear optics applications. It is used extensively in telecommunication products such as mobile phones and optical modulators, for such components as resonant crystals. Lithium applications are used in more than 60% of mobile phones.

Organic and polymer chemistry

Organolithium compounds

are widely used in the production of polymer and fine-chemicals. In the

polymer industry, which is the dominant consumer of these reagents,

alkyl lithium compounds are catalysts/initiators. in anionic polymerization of unfunctionalized olefins. For the production of fine chemicals, organolithium compounds function as strong bases and as reagents for the formation of carbon-carbon bonds. Organolithium compounds are prepared from lithium metal and alkyl halides.

Many other lithium compounds are used as reagents to prepare organic compounds. Some popular compounds include lithium aluminium hydride (LiAlH4), lithium triethylborohydride, n-butyllithium and tert-butyllithium are commonly used as extremely strong bases called superbases.

Military applications

Metallic lithium and its complex hydrides, such as Li[AlH4], are used as high-energy additives to rocket propellants. Lithium aluminum hydride can also be used by itself as a solid fuel.

The launch of a torpedo using lithium as fuel

The Mark 50 torpedo stored chemical energy propulsion system (SCEPS) uses a small tank of sulfur hexafluoride gas, which is sprayed over a block of solid lithium. The reaction generates heat, creating steam to propel the torpedo in a closed Rankine cycle.

Lithium hydride containing lithium-6 is used in thermonuclear weapons, where it serves as fuel for the fusion stage of the bomb.

Nuclear

Lithium-6 is valued as a source material for tritium production and as a neutron absorber in nuclear fusion. Natural lithium contains about 7.5% lithium-6 from which large amounts of lithium-6 have been produced by isotope separation for use in nuclear weapons. Lithium-7 gained interest for use in nuclear reactor coolants.

Lithium deuteride was used as fuel in the Castle Bravo nuclear device.

Lithium deuteride was the fusion fuel of choice in early versions of the hydrogen bomb. When bombarded by neutrons, both 6Li and 7Li produce tritium — this reaction, which was not fully understood when hydrogen bombs were first tested, was responsible for the runaway yield of the Castle Bravo nuclear test. Tritium fuses with deuterium in a fusion

reaction that is relatively easy to achieve. Although details remain

secret, lithium-6 deuteride apparently still plays a role in modern nuclear weapons as a fusion material.

Lithium fluoride, when highly enriched in the lithium-7 isotope, forms the basic constituent of the fluoride salt mixture LiF-BeF2 used in liquid fluoride nuclear reactors. Lithium fluoride is exceptionally chemically stable and LiF-BeF2 mixtures have low melting points. In addition, 7Li, Be, and F are among the few nuclides with low enough thermal neutron capture cross-sections not to poison the fission reactions inside a nuclear fission reactor.

In conceptualized (hypothetical) nuclear fusion power plants, lithium will be used to produce tritium in magnetically confined reactors using deuterium and tritium as the fuel. Naturally occurring tritium is extremely rare, and must be synthetically produced by surrounding the reacting plasma

with a 'blanket' containing lithium where neutrons from the

deuterium-tritium reaction in the plasma will fission the lithium to

produce more tritium:

- 6Li + n → 4He + 3H.

Lithium is also used as a source for alpha particles, or helium nuclei. When 7Li is bombarded by accelerated protons 8Be

is formed, which undergoes fission to form two alpha particles. This

feat, called "splitting the atom" at the time, was the first fully

man-made nuclear reaction. It was produced by Cockroft and Walton in 1932.

In 2013, the US Government Accountability Office

said a shortage of lithium-7 critical to the operation of 65 out of 100

American nuclear reactors “places their ability to continue to provide

electricity at some risk”. The problem stems from the decline of US

nuclear infrastructure. The equipment needed to separate lithium-6 from

lithium-7 is mostly a cold war leftover. The US shut down most of this

machinery in 1963, when it had a huge surplus of separated lithium,

mostly consumed during the twentieth century. The report said it would

take five years and $10 million to $12 million to reestablish the

ability to separate lithium-6 from lithium-7.

Reactors that use lithium-7 heat water under high pressure and

transfer heat through heat exchangers that are prone to corrosion. The

reactors use lithium to counteract the corrosive effects of boric acid, which is added to the water to absorb excess neutrons.

Medicine

Lithium is useful in the treatment of bipolar disorder. Lithium salts may also be helpful for related diagnoses, such as schizoaffective disorder and cyclic major depression. The active part of these salts is the lithium ion Li+. They may increase the risk of developing Ebstein's cardiac anomaly in infants born to women who take lithium during the first trimester of pregnancy.

Lithium has also been researched as a possible treatment for cluster headaches.

Biological role

Primary food sources of lithium are grains and vegetables, and, in some areas, drinking water also contains significant amounts. Human intake varies depending on location and diet.

Lithium was first detected in human organs and fetal tissues in

the late 19th century. In humans there are no defined lithium deficiency

diseases, but low lithium intakes from water supplies were associated

with increased rates of suicides, homicides and the arrest rates for

drug use and other crimes. The biochemical mechanisms of action of

lithium appear to be multifactorial and are intercorrelated with the

functions of several enzymes, hormones and vitamins, as well as with

growth and transforming factors. Evidence now appears to be sufficient

to accept lithium as essential; a provisional RDA of 1,000 µg/day is

suggested for a 70 kg adult.

Precautions

| Hazards | |

|---|---|

| GHS pictograms |

|

| GHS signal word | Danger |

| H260, H314 | |

| P223, P231+232, P280, P305+351+338, P370+378, P422 | |

| NFPA 704 | |

Lithium is corrosive

and requires special handling to avoid skin contact. Breathing lithium

dust or lithium compounds (which are often alkaline) initially irritate the nose and throat, while higher exposure can cause a buildup of fluid in the lungs, leading to pulmonary edema. The metal itself is a handling hazard because contact with moisture produces the caustic lithium hydroxide. Lithium is safely stored in non-reactive compounds such as naphtha.

Regulation

Some jurisdictions limit the sale of lithium batteries, which are the most readily available source of lithium for ordinary consumers. Lithium can be used to reduce pseudoephedrine and ephedrine to methamphetamine in the Birch reduction method, which employs solutions of alkali metals dissolved in anhydrous ammonia.

Carriage and shipment of some kinds of lithium batteries may be

prohibited aboard certain types of transportation (particularly

aircraft) because of the ability of most types of lithium batteries to

fully discharge very rapidly when short-circuited, leading to overheating and possible explosion in a process called thermal runaway.

Most consumer lithium batteries have built-in thermal overload

protection to prevent this type of incident, or are otherwise designed

to limit short-circuit currents. Internal shorts from manufacturing

defect or physical damage can lead to spontaneous thermal runaway.