IHL is inspired by considerations of humanity and the mitigation

of human suffering. "It comprises a set of rules, established by treaty

or custom, that seeks to protect persons and property/objects that are

(or may be) affected by armed conflict and limits the rights of parties

to a conflict to use methods and means of warfare of their choice". It includes "the Geneva Conventions and the Hague Conventions, as well as subsequent treaties, case law, and customary international law". It defines the conduct and responsibilities of belligerent nations, neutral nations, and individuals engaged in warfare, in relation to each other and to protected persons, usually meaning non-combatants. It is designed to balance humanitarian concerns and military necessity, and subjects warfare to the rule of law by limiting its destructive effect and mitigating human suffering.

Serious violations of international humanitarian law are called war crimes. International humanitarian law, jus in bello, regulates the conduct of forces when engaged in war or armed conflict. It is distinct from jus ad bellum which regulates the conduct of engaging in war or armed conflict and includes crimes against peace and of war of aggression. Together the jus in bello and jus ad bellum comprise the two strands of the laws of war governing all aspects of international armed conflicts.

The law is mandatory for nations bound by the appropriate treaties. There are also other customary unwritten rules of war, many of which were explored at the Nuremberg War Trials. By extension, they also define both the permissive rights of these powers as well as prohibitions on their conduct when dealing with irregular forces and non-signatories.

International humanitarian law operates on a strict division between rules applicable in international armed conflict and internal armed conflict. This dichotomy is widely criticized.

The relationship between international human rights law and international humanitarian law is disputed among international law scholars. This discussion forms part of a larger discussion on fragmentation of international law. While pluralist scholars conceive international human rights law as being distinct from international humanitarian law, proponents of the constitutionalist approach regard the latter as a subset of the former. In a nutshell, those who favor separate, self-contained regimes emphasize the differences in applicability; international humanitarian law applies only during armed conflict. On the other hand, a more systemic perspective explains that international humanitarian law represents a function of international human rights law; it includes general norms that apply to everyone at all time as well as specialized norms which apply to certain situations such as armed conflict and military occupation (i.e., IHL) or to certain groups of people including refugees (e.g., the 1951 Refugee Convention), children (the 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child), and prisoners of war (the 1949 Third Geneva Convention).

Democracies are likely to protect the rights of all individuals within their territorial jurisdiction.

Serious violations of international humanitarian law are called war crimes. International humanitarian law, jus in bello, regulates the conduct of forces when engaged in war or armed conflict. It is distinct from jus ad bellum which regulates the conduct of engaging in war or armed conflict and includes crimes against peace and of war of aggression. Together the jus in bello and jus ad bellum comprise the two strands of the laws of war governing all aspects of international armed conflicts.

The law is mandatory for nations bound by the appropriate treaties. There are also other customary unwritten rules of war, many of which were explored at the Nuremberg War Trials. By extension, they also define both the permissive rights of these powers as well as prohibitions on their conduct when dealing with irregular forces and non-signatories.

International humanitarian law operates on a strict division between rules applicable in international armed conflict and internal armed conflict. This dichotomy is widely criticized.

The relationship between international human rights law and international humanitarian law is disputed among international law scholars. This discussion forms part of a larger discussion on fragmentation of international law. While pluralist scholars conceive international human rights law as being distinct from international humanitarian law, proponents of the constitutionalist approach regard the latter as a subset of the former. In a nutshell, those who favor separate, self-contained regimes emphasize the differences in applicability; international humanitarian law applies only during armed conflict. On the other hand, a more systemic perspective explains that international humanitarian law represents a function of international human rights law; it includes general norms that apply to everyone at all time as well as specialized norms which apply to certain situations such as armed conflict and military occupation (i.e., IHL) or to certain groups of people including refugees (e.g., the 1951 Refugee Convention), children (the 1989 Convention on the Rights of the Child), and prisoners of war (the 1949 Third Geneva Convention).

Democracies are likely to protect the rights of all individuals within their territorial jurisdiction.

Two historical streams: The Law of Geneva and The Law of The Hague

Modern international humanitarian law is made up of two historical streams:

- The law of The Hague, referred to in the past as the law of war proper; and

- The law of Geneva, or humanitarian law.

The two streams take their names from a number of international

conferences which drew up treaties relating to war and conflict, in

particular the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907, and the Geneva

Conventions, the first which was drawn up in 1863. Both deal with jus in bello, which deals with the question of whether certain practices are acceptable during armed conflict.

The Law of The Hague, or the laws of war

proper, "determines the rights and duties of belligerents in the

conduct of operations and limits the choice of means in doing harm". In particular, it concerns itself with

- the definition of combatants;

- establishes rules relating to the means and methods of warfare;

- and examines the issue of military objectives.

Systematic attempts to limit the savagery of warfare only began to

develop in the 19th century. Such concerns were able to build on the

changing view of warfare by states influenced by the Age of

Enlightenment. The purpose of warfare was to overcome the enemy state,

which could be done by disabling the enemy combatants. Thus, "the

distinction between combatants and civilians, the requirement that

wounded and captured enemy combatants must be treated humanely, and that

quarter must be given, some of the pillars of modern humanitarian law,

all follow from this principle".

The Law of Geneva

The massacre of civilians in the midst of armed conflict has a long and dark history. Selected examples include

- the massacres of the Kalingas by Ashoka in India;

- the Crusader massacres of Jews and Muslims in the Siege of Jerusalem (1099);

- the Mongol massacres during the Mongol invasions, such as the sack of Baghdad; and

- the massacre of Indians by Timur (Tamerlane),

to name only a few examples drawn from a long list in history. Fritz

Munch sums up historical military practice before 1800: "The essential

points seem to be these: In battle and in towns taken by force,

combatants and non-combatants were killed and property was destroyed or

looted." In the 17th century, the Dutch jurist Hugo Grotius,

widely regarded as the founder or father of public international law,

wrote that "wars, for the attainment of their objects, it cannot be

denied, must employ force and terror as their most proper agents".

Humanitarian norms in history

Even

in the midst of the carnage of history, however, there have been

frequent expressions and invocation of humanitarian norms for the

protection of the victims of armed conflicts: the wounded, the sick and

the shipwrecked. These date back to ancient times.

In the Old Testament, the King of Israel prevents the slaying of

the captured, following the prophet Elisha's admonition to spare enemy

prisoners. In answer to a question from the King, Elisha said, "You

shall not slay them. Would you slay those whom you have taken captive

with your sword and with your bow? Set bread and water before them, that

they may eat and drink and go to their master."

In ancient India there are records (the Laws of Manu,

for example) describing the types of weapons that should not be used:

"When he fights with his foes in battle, let him not strike with weapons

concealed (in wood), nor with (such as are) barbed, poisoned, or the

points of which are blazing with fire."

There is also the command not to strike a eunuch nor the enemy "who

folds his hands in supplication ... Nor one who sleeps, nor one who has

lost his coat of mail, nor one who is naked, nor one who is disarmed,

nor one who looks on without taking part in the fight."

Islamic law states that "non-combatants

who did not take part in fighting such as women, children, monks and

hermits, the aged, blind, and insane" were not to be molested. The first Caliph, Abu Bakr,

proclaimed, "Do not mutilate. Do not kill little children or old men or

women. Do not cut off the heads of palm trees or burn them. Do not cut

down fruit trees. Do not slaughter livestock except for food."

Islamic jurists have held that a prisoner should not be killed, as he

"cannot be held responsible for mere acts of belligerency".

Islamic law did not spare all non-combatants, however. In the

case of those who refused to convert to Islam, or to pay an alternative

tax, Muslims "were allowed in principle to kill any one of them,

combatants or noncombatants, provided they were not killed treacherously

and with mutilation".

Codification of humanitarian norms

The

most important antecedent of IHL is the current Armistice Agreement and

Regularization of War, signed and ratified in 1820 between the

authorities of the then Government of Great Colombia and the Chief of

the Expeditionary Forces of the Spanish Crown, in the Venezuelan city of

santa Ana de Trujillo. This treaty was signed under the conflict of

Independence, being the first of its kind in the West.

It was not until the second half of the 19th century, however,

that a more systematic approach was initiated. In the United States, a

German immigrant, Francis Lieber, drew up a code of conduct in 1863, which came to be known as the Lieber Code, for the Union Army during the American Civil War.

The Lieber Code included the humane treatment of civilian populations

in the areas of conflict, and also forbade the execution of POWs.

At the same time, the involvement during the Crimean War of a number of such individuals as Florence Nightingale and Henry Dunant, a Genevese businessman who had worked with wounded soldiers at the Battle of Solferino, led to more systematic efforts to prevent the suffering of war victims. Dunant wrote a book, which he titled A Memory of Solferino, in which he described the horrors he had witnessed. His reports were so shocking that they led to the founding of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) in 1863, and the convening of a conference in Geneva in 1864, which drew up the Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded in Armies in the Field.

The Law of Geneva is directly inspired by the principle of humanity. It relates to those who are not participating in the conflict, as well as to military personnel hors de combat. It provides the legal basis for protection and humanitarian assistance carried out by impartial humanitarian organizations such as the ICRC.[24] This focus can be found in the Geneva Conventions.

Geneva Conventions

The First Geneva Convention of 1864.

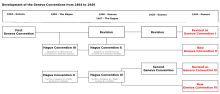

Progression of Geneva Conventions from 1864 to 1949.

The Geneva Conventions are the result of a process that

developed in a number of stages between 1864 and 1949. It focused on the

protection of civilians and those who can no longer fight in an armed

conflict. As a result of World War II, all four conventions were

revised, based on previous revisions and on some of the 1907 Hague

Conventions, and readopted by the international community in 1949. Later

conferences have added provisions prohibiting certain methods of

warfare and addressing issues of civil wars.

The first three Geneva Conventions were revised, expanded, and replaced, and the fourth one was added, in 1949.

- The Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field was adopted in 1864. It was significantly revised and replaced by the 1906 version, the 1929 version, and later the First Geneva Convention of 1949.

- The Geneva Convention for the Amelioration of the Condition of Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea was adopted in 1906. It was significantly revised and replaced by the Second Geneva Convention of 1949.

- The Geneva Convention relative to the Treatment of Prisoners of War was adopted in 1929. It was significantly revised and replaced by the Third Geneva Convention of 1949.

- The Fourth Geneva Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War was adopted in 1949.

There are three additional amendment protocols to the Geneva Convention:

- Protocol I (1977): Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of International Armed Conflicts. As of 12 January 2007 it had been ratified by 167 countries.

- Protocol II (1977): Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Protection of Victims of Non-International Armed Conflicts. As of 12 January 2007 it had been ratified by 163 countries.

- Protocol III (2005): Protocol Additional to the Geneva Conventions of 12 August 1949, and relating to the Adoption of an Additional Distinctive Emblem. As of June 2007 it had been ratified by seventeen countries and signed but not yet ratified by an additional 68.

The Geneva Conventions of 1949 may be seen, therefore, as the result

of a process which began in 1864. Today they have "achieved universal

participation with 194 parties". This means that they apply to almost

any international armed conflict.

The Additional Protocols, however, have yet to achieve near-universal

acceptance, since the United States and several other significant

military powers (like Iran, Israel, India and Pakistan) are currently

not parties to them.

Historical convergence between IHL and the laws of war

With the adoption of the 1977 Additional Protocols to the Geneva Conventions,

the two strains of law began to converge, although provisions focusing

on humanity could already be found in the Hague law (i.e. the protection

of certain prisoners of war and civilians in occupied territories). The

1977 Additional Protocols, relating to the protection of victims in

both international and internal conflict, not only incorporated aspects

of both the Law of The Hague and the Law of Geneva, but also important

human rights provisions.

Basic rules of IHL

- Persons who are hors de combat (outside of combat), and those who are not taking part in hostilities in situation of armed conflict (e.g., neutral nationals), shall be protected in all circumstances.

- The wounded and the sick shall be cared for and protected by the party to the conflict which has them in its power. The emblem of the "Red Cross", or of the "Red Crescent," shall be required to be respected as the sign of protection.

- Captured persons must be protected against acts of violence and reprisals. They shall have the right to correspond with their families and to receive relief.

- No one shall be subjected to torture or to cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment.

- Parties to a conflict do not have an unlimited choice of methods and means of warfare.

- Parties to a conflict shall at all times distinguish between combatants and non-combatants. Attacks shall be directed solely against legitimate military targets.

Examples

Well-known examples of such rules include the prohibition on attacking doctors or ambulances displaying a red cross.

It is also prohibited to fire at a person or vehicle bearing a white

flag, since that, being considered the flag of truce, indicates an

intent to surrender or a desire to communicate. In either case, the

persons protected by the Red Cross or the white flag are expected to

maintain neutrality, and may not engage in warlike acts themselves;

engaging in war activities under a white flag or a red cross is itself a

violation of the laws of war.

These examples of the laws of war address

- declarations of war;

- acceptance of surrender;

- the treatment of prisoners of war;

- the avoidance of atrocities;

- the prohibition on deliberately attacking non-combatants; and

- the prohibition of certain inhumane weapons.

It is a violation of the laws of war to engage in combat without

meeting certain requirements, among them the wearing of a distinctive uniform

or other easily identifiable badge, and the carrying of weapons openly.

Impersonating soldiers of the other side by wearing the enemy's uniform

is allowed, though fighting in that uniform is unlawful perfidy, as is the taking of hostages.

Later additions

International

humanitarian law now includes several treaties that outlaw specific

weapons. These conventions were created largely because these weapons

cause deaths and injuries long after conflicts have ended. Unexploded land mines have caused up to 7,000 deaths a year; unexploded bombs, particularly from cluster bombs

that scatter many small "bomblets", have also killed many. An estimated

98% of the victims are civilian; farmers tilling their fields and

children who find these explosives have been common victims. For these

reasons, the following conventions have been adopted:

- The Convention on Prohibitions or Restrictions on the Use of Certain Conventional Weapons Which May Be Deemed to Be Excessively Injurious or to Have Indiscriminate Effects (1980), which prohibits weapons that produce non-detectable fragments, restricts (but does not eliminate) the use of mines and booby-traps, prohibits attacking civilians with incendiary weapons, prohibits blinding laser weapons, and requires the warring parties to clear unexploded ordnance at the end of hostilities;

- The Convention on the Prohibition of the Use, Stockpiling, Production and Transfer of Anti-Personnel Mines and on their Destruction (1997), also called the Ottawa Treaty or the Mine Ban Treaty, which completely bans the stockpiling (except to a limited degree, for training purposes) and use of all anti-personnel land mines;

- The Optional Protocol on the Involvement of Children in Armed Conflict (2000), an amendment to the Convention on the Rights of the Child (1989), which forbids the enlistment of anyone under the age of eighteen for armed conflict; and

- The Convention on Cluster Munitions (2008), which prohibits the use of bombs that scatter bomblets, many of which do not explode and remain dangerous long after a conflict has ended.

International Committee of the Red Cross

Emblem of the ICRC

The ICRC is the only institution explicitly named under international

humanitarian law as a controlling authority. The legal mandate of the

ICRC stems from the four Geneva Conventions of 1949, as well as from its

own Statutes.

| “ | The International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) is an impartial, neutral, and independent organization whose exclusively humanitarian mission is to protect the lives and dignity of victims of war and internal violence and to provide them with assistance. | ” |

| — Mission of ICRC | ||

Violations and punishment

During conflict, punishment for violating the laws of war may consist of a specific, deliberate and limited violation of the laws of war in reprisal.

Combatants who break specific provisions of the laws of war lose the protections and status afforded to them as prisoners of war, but only after facing a "competent tribunal". At that point, they become unlawful combatants, but must still be "treated with humanity and, in case of trial, shall not be deprived of the rights of fair and regular trial", because they are still covered by GC IV, Article 5.

Spies and terrorists

are only protected by the laws of war if the "power" which holds them

is in a state of armed conflict or war, and until they are found to be

an "unlawful combatant". Depending on the circumstances, they may be

subject to civilian law or a military tribunal for their acts. In

practice, they have often have been subjected to torture and execution. The laws of war neither approve nor condemn such acts, which fall outside their scope.

Spies may only be punished following a trial; if captured after

rejoining their own army, they must be treated as prisoners of war.

Suspected terrorists who are captured during an armed conflict, without

having participated in the hostilities, may be detained only in

accordance with the GC IV, and are entitled to a regular trial. Countries that have signed the UN Convention Against Torture have committed themselves not to use torture on anyone for any reason.

After a conflict has ended, persons who have committed any breach

of the laws of war, and especially atrocities, may be held individually

accountable for war crimes through process of law.

Key provisions and principles applicable to civilians

The

Fourth Geneva Convention focuses on the civilian population. The two

additional protocols adopted in 1977 extend and strengthen civilian

protection in international (AP I) and non-international (AP II) armed

conflict: for example, by introducing the prohibition of direct attacks

against civilians. A "civilian" is defined as "any person not belonging

to the armed forces", including non-nationals and refugees.

However, it is accepted that operations may cause civilian casualties.

Luis Moreno Ocampo, chief prosecutor of the international criminal

court, wrote in 2006: "International humanitarian law and the Rome statute

permit belligerents to carry out proportionate attacks against military

objectives, even when it is known that some civilian deaths or injuries

will occur. A crime occurs if there is an intentional attack directed

against civilians (principle of distinction) ... or an attack is

launched on a military objective in the knowledge that the incidental

civilian injuries would be clearly excessive in relation to the

anticipated military advantage (principle of proportionality)."

The provisions and principles of IHL which seek to protect civilians are:

IHL provisions and principles protecting civilians

Principle of distinction

The principle of distinction

protects civilian population and civilian objects from the effects of

military operations. It requires parties to an armed conflict to

distinguish at all times, and under all circumstances, between

combatants and military objectives on the one hand, and civilians and

civilian objects on the other; and only to target the former. It also

provides that civilians lose such protection should they take a direct

part in hostilities.

The principle of distinction has also been found by the ICRC to be

reflected in state practice; it is therefore an established norm of

customary international law in both international and non-international

armed conflicts.

Necessity and proportionality

Necessity and proportionality

are established principles in humanitarian law. Under IHL, a

belligerent may apply only the amount and kind of force necessary to

defeat the enemy. Further, attacks on military objects must not cause

loss of civilian life considered excessive in relation to the direct

military advantage anticipated. Every feasible precaution must be taken by commanders to avoid civilian casualties.

The principle of proportionality has also been found by the ICRC to

form part of customary international law in international and

non-international armed conflicts.

Principle of humane treatment

The principle of humane treatment requires that civilians be treated humanely at all times.

Common Article 3 of the GCs prohibits violence to life and person

(including cruel treatment and torture), the taking of hostages,

humiliating and degrading treatment, and execution without regular trial

against non-combatants, including persons hors de combat

(wounded, sick and shipwrecked). Civilians are entitled to respect for

their physical and mental integrity, their honour, family rights,

religious convictions and practices, and their manners and customs.

This principle of humane treatment has been affirmed by the ICRC as a

norm of customary international law, applicable in both international

and non-international armed conflicts.

Principle of non-discrimination

The

principle of non-discrimination is a core principle of IHL. Adverse

distinction based on race, sex, nationality, religious belief or

political opinion is prohibited in the treatment of prisoners of war, civilians, and persons hors de combat.

All protected persons shall be treated with the same consideration by

parties to the conflict, without distinction based on race, religion,

sex or political opinion. Each and every person affected by armed conflict is entitled to his fundamental rights and guarantees, without discrimination.

The prohibition against adverse distinction is also considered by the

ICRC to form part of customary international law in international and

non-international armed conflict.

Women and children

Women

and children are granted preferential treatment, respect and

protection. Women must be protected from rape and from any form of

indecent assault. Children under the age of eighteen must not be

permitted to take part in hostilities.

Gender and culture

Gender

IHL

emphasises, in various provisions in the GCs and APs, the concept of

formal equality and non-discrimination. Protections should be provided

"without any adverse distinction founded on sex". For example, with

regard to female prisoners of war, women are required to receive

treatment "as favourable as that granted to men".

In addition to claims of formal equality, IHL mandates special

protections to women, providing female prisoners of war with separate

dormitories from men, for example, and prohibiting sexual violence against women.

The reality of women's and men's lived experiences of conflict

has highlighted some of the gender limitations of IHL. Feminist critics

have challenged IHL's focus on male combatants and its relegation of

women to the status of victims, and its granting them legitimacy almost

exclusively as child-rearers. A study of the 42 provisions relating to

women within the Geneva Conventions and the Additional Protocols found

that almost half address women who are expectant or nursing mothers. Others have argued that the issue of sexual violence against men in conflict has not yet received the attention it deserves.

Soft-law instruments have been relied on to supplement the protection of women in armed conflict:

- UN Security Council Resolutions 1888 and 1889 (2009), which aim to enhance the protection of women and children against sexual violations in armed conflict; and

- Resolution 1325, which aims to improve the participation of women in post-conflict peacebuilding.

Read together with other legal mechanisms, in particular the UN Convention for the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women (CEDAW), these can enhance interpretation and implementation of IHL.

In addition, international criminal tribunals (like the International Criminal Tribunals for the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda) and mixed tribunals (like the Special Court for Sierra Leone)

have contributed to expanding the scope of definitions of sexual

violence and rape in conflict. They have effectively prosecuted sexual

and gender-based crimes committed during armed conflict. There is now

well-established jurisprudence on gender-based crimes. Nonetheless,

there remains an urgent need to further develop constructions of gender

within international humanitarian law.

Culture

IHL has generally not been subject to the same debates and criticisms of "cultural relativism" as have international human rights.

Although the modern codification of IHL in the Geneva Conventions and

the Additional Protocols is relatively new, and European in name, the

core concepts are not new, and laws relating to warfare can be found in

all cultures.

ICRC studies on the Middle East, Somalia, Latin America, and the

Pacific, for example have found that there are traditional and

long-standing practices in various cultures that preceded, but are

generally consistent with, modern IHL. It is important to respect local

and cultural practices that are in line with IHL. Relying on these links

and on local practices can help to promote awareness of and adherence to IHL principles among local groups and communities.

Durham cautions that, although traditional practices and IHL

legal norms are largely compatible, it is important not to assume

perfect alignment. There are areas in which legal norms and cultural

practices clash. Violence against women, for example, is frequently

legitimised by arguments from culture, and yet is prohibited in IHL and

other international law. In such cases, it is important to ensure that

IHL is not negatively affected.