| 2019 Amazon rainforest wildfires | |

|---|---|

|

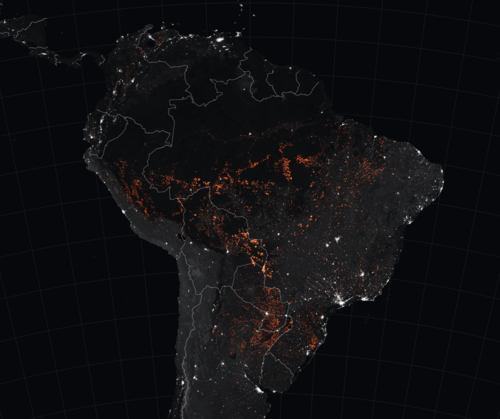

Locations of fires, marked in orange, which were detected by MODIS from August 15 to August 22, 2019

| |

| Location | Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, Paraguay |

| Statistics | |

| Total fires | >40,000 |

| Date(s) | January 2019 — ongoing |

| Burned area | 906,000 hectares (2,240,000 acres) |

| Cause | Slash-and-burn approach to deforest land for agriculture and effects of climate change due to unusually longer dry season and above average temperatures around worldwide during July and August |

| Fatalities | 2 |

| Map | |

Amazon rainforest ecoregions as delineated by the WWF in white and the Amazon drainage basin in blue. | |

The 2019 Amazon rainforest wildfires season saw a year-to-year surge in fires occurring in the Amazon rainforest and Amazon biome within Brazil, Bolivia, Paraguay, and Peru during that year's Amazonian tropical dry season. Fires normally occur around the dry season as slash-and-burn methods are used to clear the forest to make way for agriculture, livestock, logging, and mining, leading to deforestation of the Amazon rainforest. Such activity is generally illegal within these nations, but enforcement of environmental protection can be lax. The increased rates of fire counts in 2019 led to international concern about the fate of the Amazon rainforest, which is the world's largest carbon dioxide sink and plays a significant role in global climate change.

The increased rates were first reported by Brazil's National Institute for Space Research (Instituto Nacional de Pesquisas Espaciais, INPE) in June and July 2019 through satellite monitoring systems, but international attention was drawn to the situation by August 2019 when NASA corroborated INPE's findings, and smoke from the fires, visible from satellite imagery, darkened the city of São Paulo despite being thousands of kilometers from the Amazon. As of August 29, 2019, INPE reported more than 80,000 fires across all of Brazil, a 77% year-to-year increase for the same tracking period, with more than 40,000 in the Brazil's Legal Amazon (Amazônia Legal or BLA), which contains 60% of the Amazon. Similar year-to-year increases in fires were subsequently reported in Bolivia, Paraguay and Peru, with the 2019 fire counts within each nation of over 19,000, 11,000 and 6,700, respectively, as of August 29, 2019. It is estimated that over 906 thousand hectares (2.24×106 acres; 9,060 km2; 3,500 sq mi) of forest within the Amazon biome has been lost to fires in 2019. In addition to the impact on global climate, the fires created environmental concerns from the excess carbon dioxide and carbon monoxide within the fires' emissions, potential impacts on the biodiversity of the Amazon, and threats to indigenous tribes that live within the forest.

The increased rate of fires in Brazil has raised the most concerns as international leaders, particularly French president Emmanuel Macron, and environmental non-government organizations (ENGOs) attributed these to Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro's pro-business policies that had weakened environmental protections and have encouraged deforestation of the Amazon after he took office in January 2019. Bolsonaro initially remained ambivalent and rejected international calls to take action, asserting that the criticism was sensationalist. Following increased pressure from the international community at the 45th G7 summit and a threat to reject the pending European Union–Mercosur free trade agreement, Bolsonaro dispatched over 44,000 Brazilian troops and allocated funds to fight the fires, and later signed a decree to prevent such fires for a sixty day period.

Other Amazonian countries have been more open for aid and reduce the rate of fires. While Bolivian president Evo Morales was similarly blamed for past policies that encouraged deforestation, Morales has since taken proactive measures to fight the fires and seek aid from other countries. At the G7 summit, Macron negotiated with the other nations to allocate US$22 million for emergency aid to the Amazonian countries affected by the fires.

The Amazon forest and deforestation

There are 670 million ha (1.7 billion acres; 6.7 million km2; 2.6 million sq mi) of Amazon rainforest. Human-driven deforestation of the Amazon rainforest has been a major concern for decades as the rainforest's impact on the global climate has been measured. From a global climate perspective, the Amazon has been the world's largest carbon dioxide sink, and estimated to capture up to 25% of global carbon dioxide generation into plants and other biomass. Without this sink, atmospheric carbon dioxide

concentrations would increase and contribute towards higher global

temperatures, thus making the viability of the Amazon a global concern.

Further, when the forest is lost through fire, additional carbon

dioxide is released to the atmosphere, and could potentially contribute

significantly to the total carbon dioxide content. The flora also generates significant quantities of water vapor through transpiration which travel large distances to other parts of South America via atmospheric rivers and contribute to the precipitation in these areas. Due to ongoing global climate change,

environmental scientists have raised concerns that the Amazon could

reach a "tipping point" where it would irreversibly die out, the land

becoming more savanna than forest, under certain climate change conditions which are exacerbated by anthropogenic activities.

Human-driven deforestation of the Amazon is used to clear land for agriculture, livestock, and mining, and for its lumber. Most forest is typically cleared using slash-and-burn

processes; huge amounts of biomass are removed by first pulling down

the trees in the Amazon using bulldozers and giant tractors during the

wet season (November through June), followed by torching the tree trunks

several months later in the dry season (July through October). Fires are most common in July though August.

In some cases, workers performing the burn are unskilled, and may

inadvertently allow these fires to spread. While most countries in the

Amazon do have laws and environmental enforcement against deforestation,

these are not well enforced, and much of the slash-and-burn activity is

done illegally.

Deforestation leads to a large number of observed fires across

the Amazon during the dry season, usually tracked by satellite data.

While it is possible for naturally-occurring wildfires to occur in the

Amazon, the chances are far less likely to occur, compared to those in California or in Australia. Even with global warming,

spontaneous fires in the Amazon cannot come from warm weather alone,

but warm weather is capable of exacerbating the fires once started as

there will be drier biomass available for the fire to spread.

Alberto Setzer of INPE estimated that 99% of the wildfires in the

Amazon basin are a result of human actions, either on purpose or

accidentally.

Manmade fires in the Amazon also tend to elevate their smoke into the

higher atmosphere due to the more intense burn of the dry biomass,

compared with naturally occurring wildfires.

Further evidence of the fires being caused by human activity is due to

their clustering near roads and existing agricultural areas rather than

remote parts of the forest.

Fires in Brazil

Past deforestation and fires in Brazil

Brazil's role in deforestation of the Amazon rainforest has been a

significant issue since the 1970s, as 60% of the Amazon is contained

within Brazil, designated as the Brazil's Legal Amazon (Amazônia Legal, BLA).

Since the 1970s, Brazil has consumed approximately 12 percent of the

forest, representing roughly 77.7 million ha (192 million acres)—an area

larger than that of the US state of Texas.

Most of the deforestation has been for natural resources for the

logging industry and land clearing for agricultural and mining use. Forest removal to make way for cattle ranching

was the leading cause of deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon from the

mid-1960s on. The Amazon region has become the largest cattle ranching

territory in the world. According to the World Bank, some 80% of deforested land is used for cattle ranching. Seventy per cent of formerly forested land in the Amazon, and 91% of land deforested since 1970, is used for livestock pasture. According to the Center for International Forestry Research

(CIFOR), "between 1990 and 2001 the percentage of Europe's processed

meat imports that came from Brazil rose from 40 to 74 percent" and by

2003 "for the first time ever, the growth in Brazilian cattle

production, 80 percent of which was in the Amazon[,] was largely export

driven."

The Brazilian states of Pará, Mato Grosso, and Rondônia, located along

the southern border of the Amazon rainforest, are in what is called the

"deforestation arc".

Deforestation within Brazil is partially driven by growing demand for beef and soy exports, particularly to China and Hong Kong.

Brazil is one of the largest exporters of beef, accounting for more

than 20% of global trade of the commodity. Brazil exported over 1.6

million tonnes of beef in 2018, the highest volume in recorded history.

Brazil's cattle herd has increased by 56% over the last two decades.

Ranchers wait until the dry season to slash-and-burn to give time for

the cattle to graze.

While slash-and-burn can be controlled, unskilled farmers may end up

causing wildfires. Wildfires have increased as the agricultural sector

has pushed into the Amazon basin and spurred deforestation. In recent years, "land-grabbers" (grileiros)

have been illegally cutting deep into the forest in "Brazil's

indigenous territories and other protected forests throughout the

Amazon".

Number of fires in Brazil's Amazônia Legal between January 1 and August 26 by year, reported by INPE

Past data from INPE has shown the number of fires with the BLA from

January to August in any year to be routinely higher than 60,000 fires

from 2002 to 2007 and as high as 90,000 in 2003. Fire counts have generally been higher in years of drought (2007 and 2010), which are often coupled with El Niño events.

Within international attention on the protection of the Amazon

around the early 2000s, Brazil took a more proactive approach to

deforestation of the Amazon rainforest. In 2004, the Brazilian

government had established the Federal Action Plan for Prevention and

Control of Deforestation in the Amazon (PPCDAM), with the goal to reduce

the rate of deforestation through land use regulation, environmental monitoring,

and sustainable activities, promoted through partnerships at the

federal and private level, and legal penalties for violations. Brazil also invested in more effective measures to fight fires, including fire-fighting airplanes in 2012. By 2014, USAID was teaching the indigenous people how to fight fires.

As a result of enforcement of PPCDAM, the rate of deforestation in the

Brazilian Amazon dropped 83.5% of their 2004 rates by 2012. However, in 2014, Brazil fell into an economic crisis, and as part of that recovery, pushed heavily on its exports of beef and soy to help bolster its economy, which caused a reversal in the falling deforestation rates. The Brazilian government has been defunding scientific research since the economic crisis.

To support PPCDAM, the INPE began developing systems to monitor

the Amazon rainforest. One early effort was the Amazon Deforestation

Satellite Monitoring Project (PRODES), which is a highly-detailed

satellite imagery-based approach to calculate wildfires and

deforestation losses on an annual basis.

In 2015, INPE launched five complementary projects as part of the Terra

Brasilis project to monitor deforestation closer to real-time. Among

these include the Real-Time Deforestation Detection System (DETER)

satellite alert system, allowing them to capture incidents of wildfires

in 15-day cycles.

The daily data is published on the regularly updated Brazilian

Environmental Institute government website, and later corroborated with

the annual and more accurate PRODES data.

By December 2017, INPE had completed a modernization process and

had expanded its system to analyze and share data on forest fires.

It launched its new TerraMA2Q platform—software which adapts

fire-monitoring data software including the "occurrence of irregular

fires".

Although the INPE was able to provide regional fire data since 1998,

the modernization increased access. Agencies that monitor and fight

fires include the Brazilian Federal Environment and Renewable Resources

Agency (IBAMA), as well as state authorities.

The INPE receives its images daily from 10 foreign satellites,

including the Terra and Aqua satellites—part of the NASA's Earth

Observation System (EOS).

Combined, these systems are able to capture the number of fires on a

daily basis, but this number does not directly measure the area of

forest lost to these fires; instead, this is done with fortnightly

imaging data to compare the current state of the forest with reference

data to estimate acreage lost.

Jair Bolsonaro was elected as President of Brazil

in October 2018 and took office in January 2019, after which he and his

ministries changed governmental policies to weaken protection of the

rainforest and make it favorable for farmers to continue practices of

slash-and-burn clearing, thus accelerating the deforestation from previous years. Land-grabbers had used Bolsonaro's election to extend their activities into cutting in the land of the previously isolated Apurinã people in Amazonas where the "world's largest standing tracts of unbroken rainforest" are found. Upon entering office, Bolsonaro cut US$23 million from Brazil's environmental enforcement agency, making it difficult for the agency to regulate deforestation efforts.

Bolsonaro and his ministers had also segmented the environmental

agency, placing part of its control under the agricultural ministry,

which is led by the country's farming lobby, weakened protections on

natural reserves and territories belonging to indigenous people, and

encouraged businesses to file counter-land claims against regions

managed by sustainable forestry practices.

2019 Brazil dry season fires

Agricultural fires in southern Pará, Brazil in August 2019.

INPE alerted the Brazilian government to larger-than-normal growth in

the number of fires through June to August 2019. The first four months

of the year were wetter-than-average, discouraging slash-and-burn

efforts. However, with the start of the dry season in May 2019, the

number of wildfires jumped greatly.

Additionally, NOAA reported that, regionally, the temperatures in the

January-July 2019 period were the second warmest year-to-date on record.INPE reported a year-to-year increase of 88% in wildfire occurrences in June 2019.

There was further increase in the rate of deforestation in July 2019,

with the INPE estimating that more than 1,345 square kilometres

(519 sq mi; 134,500 ha; 332,000 acres) of land had been deforested in

the month and would be on track to surpass the area of Greater London by the end of the month.

The month of August 2019 saw a large growth in the number of

observed wildfires according to INPE. By August 11, Amazonas had

declared a state of emergency. The state of Acre entered into a environmental alert on August 16. In early August, local farmers in the Amazonian state of Pará placed an ad in the local newspaper calling for a queimada

or "Day of Fire" on August 10, 2019, organizing large scale

slash-and-burn operations knowing that there was little chance of

interference from the government. Shortly after, there was an increase in the number of wildfires in the region.

INPE reported on August 20 that it had detected 39,194 fires in the Amazon rainforest since January. This represented a 77 percent increase in the number of fires from the same time period in 2018.

However, the NASA-funded NGO Global Fire Emissions Database (GFED)

shows 2018 as an unusually low fire year compared to historic data from

2004–2005 which are years showing nearly double the number of counted

fires. INPE had reported that at least 74,155 fires have been detected in all of Brazil, which represents a 84-percent increase from the same period in 2018. NASA originally reported in mid-August that MODIS

satellites reported average numbers of fires in the region compared

with data from the past 15 years; the numbers were above average for the

year in the states of Amazonas and Rondônia, but below average for Mato

Grosso and Pará.

NASA later clarified that the data set they had evaluated previous was

through August 16, 2019. By August 26, 2019, NASA included more recent

MODIS imagery to confirm that the number of fires were higher than in

previous years.

INPE satellite imagery of a 70-by-70 mile area along the Purus River between Canutama and Lábrea

in the state of Amazonas, taken on August 16, 2019, showing several

plumes of smoke from wildfires, including areas that have been

deforested

By August 29, 80,000 fires had broken out in Brazil which represents a 77% rise on the same period in 2018, according to BBC.

INPE reported that in the period from January 1 to August 29, across

South America, and not exclusive to the Amazon rainforest, there were

84,957 fires in Brazil, 26,573 in Venezuela, 19,265 in Bolivia, 14,363

in Colombia, 14,969 in Argentina, 10,810 in Paraguay, 6,534 in Peru,

2,935 in Chile, 898 in Guyana, 407 in Uruguay, 328 in Ecuador, 162 in

Suriname, and 11 in French Guiana.

First media reports

While

INPE's data had been reported in international sources earlier, news of

the wildfires were not a major news story until around August 20, 2019.

On that day, the smoke plume from the fires in Rondônia and Amazonas

caused the sky to darken at around 2 p.m. over São Paulo—which is almost 2,800 kilometres (1,700 mi) away from the Amazon basin on the eastern coast. NASA and US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) also published satellite imagery from the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) on NASA's Terra satellitein alignment with INPE's own, that showed smoke plumes from the wildfires were visible from space.

INPE and NASA data, along with photographs of the ongoing fires and

impacts, caught international attention and became a rising topic on

social media, with several world leaders, celebrities, and athletes

expressing their concerns.

According to Vox,

of all the concurrent wildfires elsewhere in the world, the wildfires

in the Amazon rainforest in Brazil were the most "alarming".

Responses of the Brazilian government

In the months prior to August 2019, Bolsonaro mocked international

and environmental groups that felt his pro-business actions enabled

deforestation.

At one point in August 2019, Bolsonaro jokingly calling himself

"Captain Chainsaw" while asserting that INPE's data was inaccurate. After INPE announced an 88% increase of wildfires in July 2019, Bolsonaro claimed "the numbers were fake" and fired Ricardo Magnus Osório Galvão, the INPE director. Bolsonaro claimed Galvão was using the data to lead an "anti-Brazil campaign".

Bolsonaro had claimed that the fires had been deliberately started by

environmental NGOs, although he provided no evidence to back up the

accusation. NGOs such as WWF Brasil, Greenpeace, and the Brazilian Institute for Environmental Protection countered Bolsonaro's claims.

Bolsonaro, on August 22, argued that Brazil did not have the

resources to fight the fires, as the "Amazon is bigger than Europe, how

will you fight criminal fires in such an area?".

Historically, Brazil has been guarded about international

intervention into the BLA, as the country sees the forest as a critical

part of Brazil's economy.

Bolsonaro and his government have continued to speak out against any

international oversight of the situation. Bolsaonaro considered French

President Emmanuel Macron's comments to have a "sensationalist tone" and accusing him of interfering in what he considers is a local problem. Of Macron and German Chancellor Angela Merkel,

Bolsonaro stated: "They still haven't realized that Brazil is under new

direction. That there's now a president who is loyal to [the] Brazilian

people, who says the Amazon is ours, who says bad Brazilians can't

release lying numbers and campaign against Brazil."

Bolsonaro's foreign minister Ernesto Araújo

has also condemned the international criticism of Bolsonaro's reaction

to the wildfires, calling it "savage and unfair" treatment towards

Bolsonaro and Brazil.

Araújo stated that: "President Bolsonaro's government is rebuilding

Brazil", and that foreign nations were using the "environmental crisis"

as a weapon to stop this rebuilding.

General Eduardo Villas Bôas, former commander of the Brazilian Army,

considered the criticism of world leaders, like Macron and Canadian

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, to be directly challenging "Brazilian sovereignty", and may need to be met with military response.

With increased pressure from the international community, Bolsonaro

appeared more willing to take proactive steps against the fires, saying

by August 23, 2019, that his government would take a "zero tolerance"

approach to environmental crimes.

He engaged the Brazilian military to help fight the wildfires on August

24, which Joint Staff member Lt. Brig. Raul Botelho stated was to

create a "positive perception" of the government's efforts. Among military support included 43,000 troops as well as four firefighting aircraft, and an allocated US$15.7 million for fire-fighting operations. Initial efforts were principally located in the state of Rondônia, but the Defense Ministry stated they plan to offer support for all seven states affected by the fires.

On August 28, Bolsonaro signed a decree banning the setting of fires in

Brazil for a period of 60 days, making exceptions for those fires made

purposely to maintain environmental forest health, to combat wildfires,

and by the indigenous people of Brazil. However, as most fires are set

illegally, it is unclear what impact this decree could have.

Rodrigo Maia, president of the Chamber of Deputies,

announced that he would form a parliamentary committee to monitor the

problem. In addition, he said that the Chamber will hold a general

commission in the following days to assess the situation and propose

solutions to the government.

After a report from Globo Rural reveal that a WhatsApp group of 70 people was involved with the Day of Fire, Jair Bolsonaro determined the opening of investigations by Federal Police.

Brazil banned clearing land by setting fire to it on 29 August 2019.

More measures taken by the Brazilian government of Jair Bolsonaro to stop the fires include:

- Accepting 4 planes from Chile to battle the fires.

- Accepting 12 million dollars of aid from the United Kingdom government

- Softening his position about aid from the G7.

- Appealing for an international conference to preserve the Amazon with participation of all countries that have some part of the Amazon rainforest in their territory

Protests against Brazilian government policies

In regards to the displacement of the indigenous people, Amnesty International

has highlighted the change in protection of lands belonging to the

indigenous people, and have called on other nations to pressure Brazil

to restore these rights, as they are also essential to protecting the

rainforest. Ivaneide Bandeira Cardoso, founder of Kanindé, a Porto Velho-based

advocacy group for indigenous communities, said Bolsonaro is directly

responsible for the escalation of forest fires throughout the Amazon

this year. Cardoso said the wildfires are a "tragedy that affects all of

humanity" since the Amazon plays an important role in the global

ecosystem as a carbon sink to reduce the effects of climate change.

Thousands of Brazilian citizens held protests in several major

cities from August 24, 2019, onward to challenge the government's

reaction to the wildfires. Protesters around the world also held events at Brazilian embassies, including in London, Paris, Mexico City, and Geneva.

Impact on the indigenous peoples of Brazil

In

addition to environmental harm, the slash-and-burn actions leading to

the wildfires have threatened the approximately 306,000 indigenous people in Brazil who reside near or within the rainforest. Bolsanaro had spoken out against the need to respect the demarcation of lands for indigenous people established in the 1988 Constitution of Brazil.

According to a CBC report on Brazil's wildfires, representatives of the

indigenous people have stated that farmers, loggers, and miners,

emboldened by the Brazilian government's policies, have forced these

people out of their lands, sometimes through violent means, and equated

their methods with genocide. Some of these tribes have vowed to fight back against those engaged in deforestation to protect their lands.

International responses

Several international governments and environmental groups raised

concerns at Bolsonaro's stance on the rainforest and the lack of

attempts by his government to slow the wildfires. Among the most vocal

was Macron, given the proximity of French Guiana to Brazil.

Macron called the Amazon wildfires an "international crisis", while

claiming the rainforest produces "20% of the world's oxygen"—a statement

disputed by academics. He said, "Our house is burning. Literally."

Discussion about the fires came into the final negotiations of the EU–Mercosur Free Trade Agreement between the EU and Mercosur, a trade bloc of Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay, and Paraguay. With the wildfires on-going, both Macron and Irish Prime Minister Leo Varadkar have stated they will refuse to ratify the trade deal unless Brazil commits to protecting the environment.

Finance minister of Finland Mika Lintilä suggested the idea of a EU ban on Brazilian beef imports until the country takes steps to stop the deforestation.

Fires in Bolivia

Background

In Bolivia, the annual seasonal chaqueo has become an "entrenched custom" that is currently encouraged by recent political decisions. The forest fires in Bolivia occurred during the dry season but they happened independently of Brazil's fires.

Bolivia has 7.7 percent of the Amazon rainforest within its borders.

The Bolivian Amazon covers 19.402 million hectares (47.94 million

acres) which comprise 37.7 percent of Bolivia's forests and 17.7 percent

of Bolivia's land mass. Bolivia's forests cover a total of 51.407 million hectares (127.03 million acres), including the Chiquitano dry forests which is part of the Amazon biome and a transition zone between the Amazon rainforest and the drier forests of the southern Chaco region.

Santa Cruz Department

By August 16, Bolivia's Santa Cruz had declared a departmental emergency because of the forest fires. From August 18 to August 23, approximately 800 thousand hectares (2.0 million acres) of the Chiquitano dry forests were destroyed, more than what was lost over a typical two-year period. By August 24, the fires had already destroyed 1,011 thousand hectares (2.50 million acres) of forestland in the Santa Cruz and were burning near Santa Cruz, Bolivia. By August 26, wildfires had destroyed over 728 thousand hectares (1.80 million acres) of Bolivia's savanna and tropical forests, according to the Bolivian Information Agency (BIA). Over a period of five days, from August 18 to August 22, 450 thousand hectares (1.1 million acres) of forest near Roboré were destroyed.

On August 25, 4,000 state employees and volunteers were fighting the fires.

By August 25, the Chiquitano has lost 650 thousand hectares

(1.6 million acres) of tropical forest within both the Amazon and the

dry forests, mostly within the Santa Cruz

province; like the Brazil fires, such fires occur during the dry

season, but the number of fires in 2019 were larger than in previous

years. Throughout August, wildfires have been spreading across four states. Jaguars, tapirs, and dozens of endangered species are threatened. By August 26, fires in the Dionisio Foianini Triangle—the

Brazil-Bolivia-Paraguay triangle had destroyed savannah and tropical

forest "near Bolivia's border with Paraguay and Brazil".

President Evo Morales

initially ignored the fires. Juan Quintana, the president's chief of

staff, had said they did not require "foreign firefighting aid". In the week of August 18, Morales dispatched soldiers and three helicopters to fight fires in an area about the size of Oregon. On August 22, Morales contracted the Colorado-based Boeing 747 Supertanker

(also known as Global SuperTanker) to conduct firefighting missions

over the Bolivian Amazon, after having previously refused to call on

external help.

The 747 Supertanker is the largest firefighting aircraft in the world,

which can hold approximately 19,000 gallons of water per trip. Morales has stated that the governments of Spain, Chile, and Paraguay have reached out to him to provide help for fighting the fires.

The government had been trying to determine the cause of the

fires, with the Bolivian land management authority attributing 87% of

the fires to illegal slash-and-burn by farmers.

Multiple NGOs assert that deforestation rates in Bolivia increased 200

percent after the government quadrupled available land for deforestation

to farmers in 2015. The land authority attributed the increase on lax

environmental enforcement.

Political opponents of Morales alleged that the Supreme Decree 3973, a mandate to further beef production in the Amazon region, is a major cause of the Bolivian fires. The Santa Cruz province is a critical area for agriculture and cattle-rearing.

Probioma's Miguel Crespo said that, "It may take up to 200 years

for the forests in Bolivia to heal. I've never seen an environmental

tragedy on this scale ...The government has detonated an environmental

disaster. In large part, this tragedy is the result of the state's

populism and development vision based on agribusiness."

Fires in Paraguay's Pantanal

By August 22, fire emergencies in Paraguay's Alto Paraguay district and the UNESCO protected Pantanal region were issued by its federal government. Paraguay President Mario Abdo Benítez was in close contact with Bolivia's Morales to coordinate response efforts.

By August 17, as wind direction changed, flames from fires in Bolivia

began to enter northern Paraguay's Three Giants natural reserve in the

Paraguayan Pantanal natural region. By August 24, when the situation had

stabilized, Paraguay had lost 39,000 hectares (96,000 acres) in the Pantanal. An Universidad Nacional de Asunción representative lamented the disaster failed to attract as much media attention as the fires in the Amazon rainforest.

While most of the Pantanal regions—140,000 and 195,000 square

kilometres (54,000 and 75,000 sq mi)—is within Brazil's borders in the

state of Mato Grosso do Sul, the natural region also extends into Mato Grosso and portions of Bolivia. It sprawls over an area estimated at between 140,000 and 195,000 square kilometres (54,000 and 75,000 sq mi). Within the Pantanal

natural region, which is located between Brazil and Bolivia, is the

"world's largest tropical wetland area". According one of the engineers

charged with monitoring satellite data showing the "evolution of the

fires", the Pantanal is a "complex, fragile, and high-risk ecosystem

because it's being transformed from a wetland to a productive system". The Pantana is bounded by the Humid Chaco to the south, the Arid Chaco dry forests to the southwest, Cerrado savannas lie to the north, east and southeast, and the Chiquitano dry forests, to the west and northwest, where thousands of hectares burned in Bolivia.

A national parks researcher said that outsiders only know the

Amazon, which is a "shame because the Pantanal is a very important

ecological place". The Paraná River, which flows through Argentina, Brazil and Paraguay, is the "second largest river system in South America".

Fires in Peru

Peru

had nearly twice the growth in the number of fires in 2019 than Brazil,

with most believed to be illegally set by ranchers, miners, and coca growers. Much of the fires are in the Madre de Dios

which borders Brazil and Bolivia, though the fires there are not a

result of those started in the other countries, according to the

regional authority. However, they are still concerned about the impact

of downwind emissions, particularly carbon monoxide, on residents of

Madre de Dios. There were 128 forest fires reported in Peru in August 2019.

Environmental impacts of the fires

Emissions

Images created by the Atmospheric Infrared Sounder which depict carbon monoxide caused by fires in the Amazon region of Brazil from Aug. 8-22, 2019.

Locations of active wildfires (marked in orange) in the Amazon as of 22 August 2019

By August 22, NASA's AIRS published maps of increased carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide resulting from Brazil's wildfires. On the same day, the European Union's Copernicus Climate Change Service reported a "discernible spike" in emissions of carbon monoxide and carbon dioxide generated by the fires.

Areas downwind of the fires have become covered with smoke, which

can potentially last upwards of months at a time if the fires are left

to burn out. Hospitals in cities like Porto Velho

had reported over three times the average number of cases of patients

suffering from the effects of smoke over the same year-to-year period in

August 2019 than in other previous years. Besides hindering breathing,

the smoke can exacerbates patients with asthma or bronchitis and have potential cancer risk, generally affecting the youth and elderly the most.

Biodiversity

Scientists at the Natural History Museum

in London, described how while some forests have adapted to fire as

"important part of a forest ecosystem's natural cycle", the Amazon

rainforest—which is "made up of lowland, wetland forests"—is "not

well-equipped to deal with fire". Other Amazon basin ecosystems, like

the Cerrado region, with its "large savannah, and lots of plants there

have thick, corky, fire resistant stems", is "fire adapted".

Mazeika Sullivan, associate professor at Ohio State University's

School of Environment and Natural Resources, explained that the fires

could have a massive toll on wildlife in the short term as many animals

in the Amazon are not adapted for extraordinary fires. Sloths, lizards, anteaters, and frogs may unfortunately perish in larger numbers than others due to their small size and lack of mobility. Endemic species, like Milton's titi and Mura's saddleback tamarin,

are believed to be beset by the fires. Aquatic species could also be

affected due to the fires changing the water chemistry into a state

unsuitable for life. Long-term effects could be more catastrophic. Parts

of the Amazon rainforest's dense canopy were destroyed by the fires therefore exposing the lower levels of the ecosystem, which then alters the energy flow of the food chain.

International actions

On

August 22, the Bishops Conference for Latin America called the fires a

"tragedy" and urged the UN, the international community, and governments

of Amazonian countries, to "take serious measures to save the world's

lungs". Colombian President Ivan Duque

stated he wanted to lead a conservation pact with the other nations

that share the Amazon rainforest with plans to present this to the UN General Assembly. Duque said, "We must understand the protection of our Mother Earth and our Amazon is a duty, a moral duty."

United Nations Secretary General António Guterres

stated on August 23, that: "In the midst of the global climate crisis,

we cannot afford more damage to a major source of oxygen and

biodiversity."

G7 Summit and emergency aid

Attention to the wildfires increased in the week prior to the G7 summit discussions on August 24–26 in Biarritz,

France, led by President Macron. Macron stated his intent to open

discussions related to the wildfires in the Brazilian part of the Amazon

and Bolsonaro's response to them.

Merkel has also backed Macron's statements and planned to make the

issue a part of the G7 discussions; via a spokesperson, Merkel stated:

"The extent of the fires in the Amazon area is shocking and threatening,

not only for Brazil and the other affected countries, but also for the

whole world."

Macron further stated that possible international statute to protect

the rainforest may be needed "if a sovereign state took concrete actions

that clearly went against the interest of the planet". Bolsonaro expressed concern to United States president Donald Trump, that with Brazil not part of the G7, the country would be unrepresented in any such debate.

Trump offered to take the position of the Brazilian government to the

meeting and said that the US government did not agree to discuss the

issue without Brazil's presence.

Trump himself was absent from the environmental portion of the summit

held on August 26, 2019, that discussed the fires and climate change,

though members of his advisory team were in attendance.

During the summit, Macron and Chilean president Sebastián Piñera negotiated with the other nations to authorize US$22 million in emergency funding to Amazonian countries to help fight the fires. The Trump administration did not approve of the measure as the funding set certain requirements on its use.

When the final negotiations were completed, Bolsonaro stated that he

would refuse those funds for Brazil, claiming that Macron's interests

were about protecting France's agricultural business in French Guiana

from Brazil's competition. Bolsonaro also criticised Macron by comparing

the Amazon fires to the Notre-Dame de Paris fire earlier in 2019, suggesting Macron should take care of their internal fires before reaching out internationally. The governors of the states of Brazil most affected by the fires pressured Bolsonaro to accept the aid given.

Bolsonaro later clarified that he would accept foreign aid for the

fires, but only if Brazil has the authority to determine how it is used.

Amazon country summit

Brazil's

Bolsonaro stated on August 28, 2019, that the countries sharing the

Amazon rainforest, excluding Venezuela, will hold a summit in Colombia

on September 6, 2019, to discuss the ongoing Amazon fire situation.

2019 wildfires in the media

The media coverage had also broadly overshadowed the Amazon fires in Bolivia, Peru, and Paraguay by the fires and international impact of those in the BLA. The Amazon wildfires also occurred shortly after major wildfires reported in Greenland and Siberia after a globally hotter-than-average June and July, drawing away coverage of these natural disasters.

Some of these photographs shared on social media were from past fire events in the Amazon or from fires elsewhere. Agence France-Presse and El Comercio published guides to help people "fact-check" on misleading photos.

Celebrity responses to Amazon wildfires

American actor Leonardo DiCaprio

said his environmental organization Earth Alliance is donating $5

million to local groups and indigenous communities to help protect the

Amazon.

Other celebrities who made public contributions include actresses Vanessa Hudgens and Lana Condor, and Japanese musician Yoshiki.

On August 26, 2019, Europe's richest man, Bernard Arnault, declared that his LVMH group will donate $11 million to aid in the fight against the Amazon rainforest wildfires.

American restaurateur Eddie Huang said he is going vegan as a result of the 2019 Amazon fires. Khloé Kardashian urged her 98 million Instagram followers to adopt a plant-based diet for the same reason.