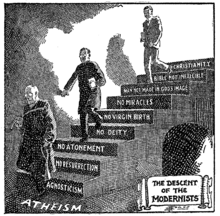

A Fundamentalist cartoon portraying Modernism as the descent from Christianity to atheism, first published in 1922 and then used in Seven Questions in Dispute by William Jennings Bryan.

The Fundamentalist–Modernist controversy is a major schism that originated in the 1920s and '30s within the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America. At issue were foundational disputes about the role of Christianity, the authority of Scripture, the death, Resurrection, and atoning sacrifice of Jesus. Two broad factions within Protestantism emerged: Fundamentalists, who insisted upon the timeless validity of each doctrine of Christian Orthodoxy, and Modernists,

who advocated a conscious adaptation of religion in response to the new

scientific discoveries and the moral pressures of the age. At first,

the schism was limited to Reformed Christianity and centered about Princeton Theological Seminary, but soon spread, affecting every denomination of Christianity in the United States. Denominations that were not initially affected, such as the Lutheran Church, eventually were embroiled in the controversy leading to a schism in the Lutheran Church.

By the end of the 1930s proponents of Theological Liberalism had, at the time, effectively won the debate, with the Modernists in control of all Mainline Protestant seminaries, publishing houses and denominational hierarchies in the United States. More conservative Christians withdrew from the mainstream, founding their own publishing houses such as Zondervan, universities (such as Biola University) and seminaries (such as Dallas Theological Seminary and Fuller Theological Seminary).

This would remain the state of affairs until the 1970s, when

conservative Protestantism reemerged, resulting in the resurgence of

traditional Christianity among the Southern Baptists, Presbyterians and others.

Background

The Old-Side–New-Side Split (1741–58) and the Old-School–New-School Split (1838–69)

Princeton Theological Seminary, headquarters of the Old School Presbyterians (1879)

Union Theological Seminary in the City of New York, headquarters of the New School Presbyterians (1910)

American Presbyterianism had gone into schism

twice in the past, and these divisions were important precursors to the

Fundamentalist–Modernist Controversy. The first was the Old Side–New Side Controversy, which occurred during the First Great Awakening,

and resulted in the Presbyterian Church in 1741 being divided into an

Old Side and New Side. The two churches reunified in 1758. The second

was the Old School–New School Controversy, which occurred in the wake of the Second Great Awakening and which saw the Presbyterian Church split into two denominations starting in 1836–38.

In 1857, the "new school" Presbyterians divided over slavery,

with the southern New School Presbyterians forming the United Synod of

the Presbyterian Church. In 1861, the Old School Presbyterians split,

with the Southern Presbyterians taking on the name the Presbyterian

Church of the Confederate States of America (which would be renamed the Presbyterian Church in the United States

in 1865). In 1864, the United Synod merged with PCCSA, with the

Southern New School Presbyterians ultimately being absorbed into an Old

School Denomination, and in 1869, the Northern New School Presbyterians

returned to the Presbyterian Church of the United States of America.

Although the controversies involved many other issues, the

overarching issue had to do with the nature of church authority and the

authority of the Westminster Confession of Faith.

The New Side/New School opposed a rigid interpretation of the

Westminster Confession. Their stance was based on spiritual

renewal/revival through an experience with the Holy Spirit based on

scripture. Therefore, they placed less emphasis on receiving a Seminary

education and the Westminster Confession (to the degree Old Side/Old

School required). Their emphasis was more on the authority of scripture

and a conversion experience, rather than on the Westminster Confession.

They argued the importance of an encounter with God mediated by the Holy Spirit. They saw the Old Side/Old School as being formalists who fetishized the Westminster Confession and Calvinism.

The Old Side/Old School responded that the Westminster Confession

was the foundational constitutional document of the Presbyterian Church

and that since the Confession was simply a summary of the Bible's

teachings, the church had a responsibility to ensure that its

ministers' preaching was in line with the Confession. They accused the

New Side/New School of being lax about the purity of the church, and

willing to allow Arminianism, unitarianism,

and other errors to be taught in the Presbyterian Church. They

criticized the New Side/School's revivals as being emotionally

manipulative and shallow. Another major division had to do with their

attitude towards other denominations: New Siders/Schoolers were willing

to set up parachurch ministries to conduct evangelism and missions

and were willing to cooperate with non-Presbyterians in doing so. The

Old Siders/Schoolers felt that evangelism and missions should be

conducted through agencies managed by the denomination and not involving

outsiders, since it would involve a watering down of the church's

theological distinctives. The two sides also had different attitudes

towards their seminary professors: Princeton Theological Seminary,

the leading institution of the Old School, demanded credal subscription

and dedicated a large part of its academic efforts to the defense of

Calvinist Orthodoxy (see Princeton theologians); while the New School's Union Theological Seminary was more willing to allow non-Presbyterians to teach at the school and was more broadminded in its academic output.

The rise of Higher Criticism and the Briggs Affair, 1880–93

American Presbyterians first became aware of Higher Criticism (the Historical-Critical method) as a development of the German academy. Between 1829 and 1850, the Princeton Review, the leading Old School theological journal under the editorship of Charles Hodge,

published 70 articles against higher criticism, and the number

increased in the years after 1850. However, it was not until the years

after 1880 that Higher Criticism really had any advocates within

American seminaries. When Higher Criticism arrived, it arrived in force.

Charles Augustus Briggs (1841–1913), the first major proponent of higher criticism within the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America and the source of a major controversy within the church, 1880–1893.

The first major proponent of Higher Criticism within the Presbyterian Church was Charles Augustus Briggs, who had studied Higher Criticism in Germany (in 1866). His inaugural address upon being made Professor of Hebrew

at Union Theological Seminary in 1876 was the first salvo of Higher

Criticism within American Presbyterianism. Briggs was active in founding

The Presbyterian Review in 1880, with Archibald Alexander Hodge,

president of Princeton Theological Seminary, initially serving as

Briggs' co-editor. In 1881, Briggs published an article in defense of William Robertson Smith which led to a series of responses and counter-responses between Briggs and the Princeton theologians in the pages of The Presbyterian Review. In 1889, B. B. Warfield became co-editor and refused to publish one of Briggs' articles, a key turning point.

In 1891, Briggs was appointed as Union's first-ever Professor of Biblical Theology.

His inaugural address, entitled "The Authority of Holy Scripture",

proved to be highly controversial. Whereas previously, Higher Criticism

had seemed a fairly technical, scholarly issue, Briggs now spelt out its

full implications. In the address, he announced that Higher Criticism

had now definitively proven that Moses did not write the Pentateuch; that Ezra did not write Ezra, Chronicles or Nehemiah; Jeremiah did not write the books of Kings or the Lamentations; David did not write most of the Psalms; Solomon wrote not the Song of Solomon or Ecclesiastes but only a few Proverbs; and Isaiah did not write half of the book of Isaiah.

The Old Testament was merely a historical record that showed man in a

lower state of moral development, with modern man having progressed

morally far beyond Noah, Abraham, Jacob, Judah, David, and Solomon. At any rate, the Scriptures as a whole are riddled with errors and the doctrine of scriptural inerrancy taught at Princeton Theological Seminary "is a ghost of modern evangelicalism to frighten children."

Not only the Westminster Confession is wrong but also the very

foundation of the Confession, the Bible, could not be used to create

theological absolutes. He now called on other rationalists in the

denomination to join him in sweeping away the dead orthodoxy of the past

and work for the unity of the entire church.

The inaugural address provoked widespread outrage in the

denomination and led Old Schoolers in the denomination to move against

him, with Francis Landey Patton taking the lead. Under the terms of the reunion of 1869, General Assembly had the right to veto all appointments to seminary professorships so at the 1891 General Assembly, held in Detroit,

Old Schoolers successfully got through a motion to veto Briggs'

appointment, which passed by a vote of 449–60. The faculty of Union

Theological Seminary, however, refused to remove Briggs, saying that it

would be a violation of scholarly freedom. In October 1892, the faculty would vote to withdraw from the denomination.

In the meantime, New York

Presbytery brought heresy charges against Briggs, but these were

defeated by a vote of 94-39. The committee that had brought the charges

then appealed to the 1892 General Assembly, held in Portland, Oregon. The General Assembly responded with its famous Portland Deliverance,

affirming that the Presbyterian Church holds that the Bible is without

error and that ministers who believe otherwise should withdraw from the

ministry. Briggs' case was remanded to New York Presbytery, which

conducted a second heresy trial for Briggs in late 1892, and in early

1893 again found Briggs not guilty of heresy. Again, Briggs' opponents

appealed to General Assembly, which in 1893 was held in Washington, D.C. The General Assembly now voted to overturn the New York decision and declared Briggs guilty of heresy. He was defrocked as a result (but only briefly since, in 1899, the Episcopal bishop of New York, Henry C. Potter, ordained him as an Episcopal priest.)

The aftermath of the Briggs Affair, 1893–1900

There

was no subsequent attempt to ferret out followers of Higher Criticism

in the years following the Portland Deliverance and the de-frocking of

Briggs. Most followers of Higher Criticism were like the 87 clergymen

who had signed the Plea for Peace and Work manifesto drafted by Henry van Dyke,

which argued that all these heresy trials were bad for the church and

that the church should be less concerned with theories about inerrancy

and more concerned with getting on with its spiritual work. Indeed, it

is probably fair to say that most clergymen in the period took the

moderate view, being willing to tolerate Higher Criticism within the

church because they were open to the points Higher Criticism was making

or they wanted to avoid the distraction and dissension of heresy trials.

For many, that came out of the traditional New School resistance to

heresy trials and the rigid imposition of the Confession.

There were two further heresy trials in subsequent years, which

would be the last major heresy trials in the history of the Presbyterian

Church in the United States of America. In late 1892, Henry Preserved Smith, Professor of Old Testament at Lane Theological Seminary, was convicted of heresy by the Presbytery of Cincinnati for teaching that there were errors in the Bible, and, upon appeal, his conviction was upheld by the General Assembly of 1894.

In 1898, Union Theological Seminary Professor of Church History Arthur Cushman McGiffert was tried by New York Presbytery, which condemned certain portions of his book A History of Christianity in the Apostolic Age,

but declined to apply sanctions. This decision was appealed to General

Assembly, but McGiffert quietly resigned from the denomination and the

charges were withdrawn.

Henry van Dyke (1852–1933), a modernist who pushed for revisions to the Westminster Confession of Faith, 1900–1910.

The movement to revise the Westminster Confession of Faith, 1900–1910

Henry van Dyke,

a modernist who had been a major supporter of Briggs in 1893, now

headed a movement of modernists and New Schoolers to revise the

Westminster Confession of Faith. Since 1889, Van Dyke had been calling

for credal revision to affirm that all dying infants (not just elect dying infants) go to heaven, to say that God loved the whole world (not just the elect), and to affirm that Christ atoned

for all mankind, not just the elect. In 1901, he chaired a 25-man

committee (with a New School majority). Also in 1901, he drew up a

non-binding summary of the church's faith. It mentioned neither biblical

inerrancy nor reprobation, affirmed God's love of all mankind, and denied that the Pope was the Antichrist. It was adopted by General Assembly in 1902 and ratified by the presbyteries in 1904.

As a result of the changes, the Arminian-leaning Cumberland Presbyterian Church

petitioned for reunification, and in 1906, over 1000 Cumberland

Presbyterian ministers joined the Presbyterian Church in the USA. The

arrival of so many liberal ministers strengthened the New School's

position in the church.

The Doctrinal Deliverance of 1910 (The Five Fundamentals)

In

1909, there was heated debate in the New York Presbytery about whether

or not to ordain three men who refused to assent to the doctrine of the virgin birth of Jesus.

(They did not deny the doctrine outright but said that they were not

prepared to affirm it.) The majority eventually ordained the men; the

minority complained to the General Assembly, and it was that complaint

that would form the basis of the subsequent controversy.

Under the order of the Presbyterian Church in the USA, the

General Assembly was not authorized to accept or dismiss the complaint.

It should have demitted the complaint to the presbytery and could have

done so with instructions that the presbytery hold a heresy trial. The

result of the trial could then be appealed to the Synod of New York and

from there to the General Assembly. However, the 1910 General Assembly,

acting outside its scope of authority, dismissed the complaint against

the three men and at the same time instructed its Committee on Bills and

Overtures to prepare a statement for governing future ordinations. The

committee reported, and the General Assembly passed the Doctrinal

Deliverance of 1910, which declared that five doctrines were "necessary

and essential" to the Christian faith:

- The inspiration of the Bible by the Holy Spirit and the inerrancy of Scripture as a result of this.

- The virgin birth of Christ.

- The belief that Christ's death was an atonement for sin.

- The bodily resurrection of Christ.

- The historical reality of Christ's miracles.

The five propositions would become known to history as the "Five

Fundamentals" and by the late 1910s, theological conservatives rallying

around the Five Fundamentals came to be known as "fundamentalists."

The Fundamentals and "Back to Fundamentals"

Lyman Stewart (1840–1923), Presbyterian layman and co-founder of Union Oil, who funded the publication of The Fundamentals: A Testimony to the Truth (1910–15).

In 1910, a wealthy Presbyterian layman, Lyman Stewart, the founder of Union Oil and a proponent of dispensationalism as taught in the newly published Scofield Reference Bible, decided to use his wealth to sponsor a series of pamphlets to be entitled The Fundamentals: A Testimony to the Truth.

These twelve pamphlets published between 1910 and 1915 eventually

included 90 essays written by 64 authors from several denominations. The

series was conservative and critical of Higher Criticism

but also broad in its approach, and the scholars who contributed

articles included several Presbyterian moderates who would later be

opposed to "fundamentalism" such as Charles R. Erdman, Sr. and Robert Elliott Speer.

It was apparently from the title of the pamphlets that the term

"fundamentalist" was coined, with the first reference to the term being

an article by Northern Baptist editor Curtis Lee Laws.

In 1915, the conservative magazine The Presbyterian

published a conservative manifesto that had been in circulation within

the denomination entitled "Back to Fundamentals". Liberal Presbyterian

magazines replied that if conservatives wanted a fight, they should

bring heresy charges in the church's courts or keep quiet. No charges

were brought.

It is worth pointing out that the only people who actually embraced the name "fundamentalist" during the 1910s were committed dispensationalists, who elevated the premillennial

return of Christ to the status of a fundamental of the Christian faith.

None of the "fundamentalist" leaders (Machen, Van Til, Macartney) in

the Presbyterian Church were dispensationalists.

Ecumenism, 1908–21

Several leading Presbyterians, notably Robert E. Speer, played a role in founding the Federal Council of Churches in 1908. This organization (which received 5% of its first year's budget from John D. Rockefeller, Jr.) was heavily associated with the Social Gospel, and with the Progressive

movement more broadly. The Council's Social Creed of the Churches was

adopted by the Presbyterian Church in 1910, but conservatives in General

Assembly were able to resist endorsing most of the Council's specific

proposals, except for those calling for Prohibition and sabbath laws.

In response to World War I,

the FCC established the General War-Time Commission to coordinate the

work of Protestant, Catholic, and Jewish programs related to the war and

work closely with the Department of War. It was chaired by Speer and liberal Union Theological Seminary

professor William Adams Brown. Following the war, they worked hard to

build on this legacy of unity. The Presbyterian Board of Foreign

Missions consequently called for a meeting of Protestant leaders on the

topic and in early 1919 the Interchurch World Movement (IWM) was established with John Mott

as its chairman. The Executive Committee of the Presbyterian Church

offered millions of dollars worth of support to help the IWM with

fundraising. When the IWM collapsed financially, the denomination was on

the hook for millions of dollars.

J. Gresham Machen (1881–1937), founder of the Orthodox Presbyterian Church and the Westminster Theological Seminary.

However, the debate between modernists and conservatives over the

issue of the IWM was small compared to the Church Union debate. In 1919,

the General Assembly sent a delegation to a national ecumenical

convention that was proposing church union, and in 1920, General

Assembly approved a recommendation which included "organic union" with

17 other denominations – the new organization, to be known as the United

Churches of Christ in America, would be a sort of "federal government"

for member churches: denominations would maintain their distinctive

internal identities, but the broader organization would be in charge of

things like missions and lobbying for things like prohibition. Under the

terms of presbyterian polity, the measure would have to be approved by the presbyteries to take effect.

The plans for Church Union were roundly denounced by the Old

School Princeton Theological Seminary faculty. It was at this point in

1920 that Princeton professor J. Gresham Machen first gained prominence within the denomination as a fundamentalist

opponent of Church Union, which he argued would destroy Presbyterian

distinctives, and effectively cede control of the denomination to

modernists and their New School allies. However, chinks were starting to

show in the Princeton faculty's armor. Charles Erdman and the president

of the seminary, William Robinson, came out in favor of the union.

Ultimately, the presbyteries defeated church union by a vote of 150-100 in 1921.

"Shall the Fundamentalists Win?" (1922)

The

splits between fundamentalists and modernists had been bubbling in the

Presbyterian Church for some time. The event which was to bring the

issue to a head was Harry Emerson Fosdick's sermon of May 21, 1922, "“Shall the Fundamentalists Win?”" Fosdick was ordained as a Baptist, but had been given special permission to preach in First Presbyterian Church in New York City.

A 1926 photograph of Harry Emerson Fosdick (1878–1969), whose 1922 sermon "Shall the Fundamentalists Win?" sparked the Fundamentalist-Modernist controversy.

In this sermon, Fosdick presented the liberals in both the

Presbyterian and Baptist denominations as sincere evangelical Christians

who were struggling to reconcile new discoveries in history, science,

and religion with the Christian faith. Fundamentalists, on the other

hand, were cast as intolerant conservatives who refused to deal with

these new discoveries and had arbitrarily drawn the line as to what was

off limits in religious discussion. Many people, Fosdick argued, simply

found it impossible to accept the virgin birth of Christ, the doctrine

of substitutionary atonement, or the literal Second Coming

of Christ in the light of modern science. Given the different points of

view within the church, only tolerance and liberty could allow for

these different perspectives to co-exist in the church.

Fosdick's sermon was re-packaged as "The New Knowledge and the

Christian Faith" and quickly published in three religious journals, and

then distributed as a pamphlet to every Protestant clergyman in the

country.

Conservative Clarence E. Macartney, pastor of Arch Street Presbyterian Church in Philadelphia,

responded to Fosdick with a sermon of his own, entitled "Shall Unbelief

Win?" which was quickly published in a pamphlet. He argued that

liberalism had been progressively "secularizing" the church and, if left

unchecked, would lead to "a Christianity of opinions and principles and

good purposes, but a Christianity without worship, without God, and

without Jesus Christ."

Led by Macartney, the Presbytery of Philadelphia requested that

the General Assembly direct the Presbytery of New York to take such

actions as to ensure that the teaching and preaching in the First

Presbyterian Church of New York City conform to the Westminster

Confession of Faith. This request would lead to over a decade of bitter

wrangling in the Presbyterian Church.

Throughout the proceedings, Fosdick's defense was led by lay elder John Foster Dulles.

William Jennings Bryan and the General Assembly of 1923

Background: Darwinism and Christianity

A giant of Old School Presbyterianism at Princeton, Charles Hodge, was one of the few Presbyterian controversialists to turn their guns on Darwinism prior to World War I. Hodge published his What is Darwinism? in 1874, three years after The Descent of Man was published, and argued that if Charles Darwin's theory excluded the design argument, it was effectively atheism and could not be reconciled with biblical Christianity.

Asa Gray responded that Christianity was compatible with Darwin's science. Both he and many other Christians accepted various forms of theistic evolution, and Darwin had not excluded the work of the Creator as a primary cause.

Most churchmen, however, took a far more prosaic attitude. In the

early period, it must have appeared far from clear that Darwin's theory

of natural selection

would come to be hegemonic among scientists, as refutations and

alternate systems were still being proposed and debated. Then, when

evolution became widely accepted, most churchmen were far less concerned

with refuting it than they were with establishing schemes whereby

Darwinism could be reconciled with Christianity. This was true even

among prominent Old Schoolers at Princeton Theological Seminary such as

Charles Hodge's successors A. A. Hodge and B. B. Warfield who came to endorse the ideas now described as theistic evolution.

William Jennings Bryan

William Jennings Bryan (1860–1925), 1907.

William Jennings Bryan, a former lawyer who had been brought up in the Arminian Cumberland Presbyterian Church (which would merge with the PC-USA in 1906) and who was also a Presbyterian ruling elder, was elected to Congress in 1890, then became the Democratic presidential candidate for three unsuccessful presidential bids in 1896, 1900, and 1908.

After his 1900 defeat, Bryan re-examined his life and concluded that he

had let his passion for politics obscure his calling as a Christian.

Beginning in 1900, he began lecturing on the Chautauqua

circuit, where his speeches often involved religious as well as

political themes. For the next 25 years until his death, Bryan was one

of the most popular Chautauqua lecturers and he spoke in front of

hundreds of thousands of people.

By 1905, Bryan had concluded that Darwinism and the modernism of

Higher Criticism were allies in promoting liberalism within the church,

thereby in his view undermining the foundations of Christianity. In

lectures from 1905, Bryan spoke out against the spread of Darwinism,

which he characterized as involving "the operation of the law of hate –

the merciless law by which the strong crowd out and kill off the weak",

and warned that it could undermine the foundations of morality. In 1913

he became Woodrow Wilson's secretary of state, then resigned in 1915 because he believed that the Wilson administration was about to enter World War I in response to the sinking of the RMS Lusitania and he opposed American intervention in a European war.

When the US did finally join World War I in 1917, Bryan

volunteered for the army, though he was never allowed to enlist. At a

time of widespread revulsion at alleged German atrocities, Bryan linked

evolution to Germany, and claimed that Darwinism provided a justification for the strong to dominate the weak and was therefore the source of German militarism. He drew on reports by the entomologist Vernon Kellogg of German officers discussing the Darwinian rationale for their declaration of war, and the sociologist Benjamin Kidd's book The Science of Power which contended that Nietzsche's philosophy represented an interpretation of Darwinism, to conclude that Nietzsche's and Darwin's ideas were the impetus for German nationalism

and militarism. Bryan argued that Germany's militarism and "barbarism"

came from their belief that the "struggle for survival" described in

Darwin's On the Origin of Species applied to nations as well as to individuals,

and that "The same science that manufactured poisonous gases to

suffocate soldiers is preaching that man has a brute ancestry and

eliminating the miraculous and the supernatural from the Bible."

Bryan was, in essence, fighting what would later be called social Darwinism, social and economic ideas owing as much to Herbert Spencer and Thomas Malthus as to Darwin, and viewed by modern biologists as a misuse of his theory. Germany, or so Bryan's argument ran, had replaced Christ's teachings with Nietzsche's philosophy based on ideas of survival of the fittest, and the implication was that America would suffer the same fate if unchecked. This fear was reinforced by the report of the psychologist James H. Leuba's

1916 study indicating that a considerable number of college students

lost their faith during the four years they spent in college.

Bryan launched his campaign against Darwinism in 1921 when he was invited to give the James Sprunt Lectures at Virginia's Union Theological Seminary. At the end of one, The Menace of Darwinism,

he said that "Darwinism is not a science at all; it is a string of

guesses strung together" and that there is more science in the Bible's

"And God said, Let the earth bring forth the living creature ..." than in all of Darwin. These lectures were published and became a national bestseller.

Now that Bryan had linked Darwinism and Higher Criticism as the

twin evils facing the Presbyterian Church, Harry Emerson Fosdick

responded by defending Darwinism, as well as Higher Criticism, from

Bryan's attack. In the early 1920s, Bryan and Fosdick squared off

against each other in a series of articles and replies in the pages of

the New York Times.

The General Assembly of 1923

In these circumstances, when General Assembly met in 1923 in Indianapolis, Bryan was determined to strike against Darwinism and against Fosdick, so he organized a campaign to have himself elected as Moderator of the General Assembly. He lost the election by a vote of 451–427 to the Rev. Charles F. Wishart, president of the College of Wooster, a strong proponent of allowing evolution to be taught at Presbyterian-run colleges and universities.

Undaunted, Bryan took to opposing Darwinism on the floor of the General Assembly,

the first time General Assembly had debated the matter. He proposed a

resolution that the denomination should cease payments to any school,

college, or university where Darwinism was taught. Opponents argued that

there were plenty of Christians in the church who believed in evolution.

Ultimately, Bryan could not convince even Machen to back his position,

and the Assembly simply approved a resolution condemning materialistic

(as opposed to theistic) evolutionary philosophy.

The major question dealt with at the General Assembly of 1923 was

not, however, Darwinism. It was the question of what to do about Harry

Emerson Fosdick and his provocative sermon of the previous year. The

Committee on Bills and Overtures recommended that the assembly declare

its continuing commitment to the Westminster Confession, but leave the

matter to New York Presbytery, which was investigating. The Committee's

minority report recommended a declaration re-affirming the

denomination's commitment to the Five Fundamentals of 1910 and to

require New York Presbytery to force First Presbyterian Church to

conform to the Westminster Confession. A fiery debate ensued, with Bryan

initially seeking a compromise to drop the prosecution of Fosdick in

exchange for a reaffirmation of the Five Fundamentals. When this proved

impossible, he lobbied intensely for the minority report, and was

successful in having the minority report adopted by a vote of 439–359.

Even before the end of General Assembly, this decision was

controversial. 85 commissioners filed an official protest, arguing that

the Fosdick case was not properly before the General Assembly, and that,

as the General Assembly was a court, not a legislative body, the Five

Fundamentals could not be imposed upon church officers without violating

the constitution of the church. At the same time, Henry Sloane Coffin

of Madison Avenue Presbyterian Church in New York City issued a

statement saying that he did not accept the Five Fundamentals and that

if Fosdick were removed from his pulpit, they would need to get rid of

him too.

The Auburn Affirmation (1923–24)

Even before the General Assembly of 1923, Robert Hastings Nichols, a history professor at Auburn Theological Seminary

was circulating a paper in which he argued that the Old School-New

School reunion of 1870 and the merger with the Cumberland Presbyterian

Church of 1906 had created a church specifically designed to accommodate

doctrinal diversity.

Two weeks after the General Assembly of 1923, 36 clergymen met in Syracuse, New York, and, using Nichols' paper as a base, ultimately issued a declaration known to history as the Auburn Affirmation.

The Auburn Affirmation opened by affirming the Westminster

Confession of Faith, but argued that within American Presbyterianism,

there had been a long tradition of freedom of interpretation of the

Scriptures and the Confession. The General Assembly's issuance of the

Five Fundamentals not only eroded this tradition, but it flew in the

face of the Presbyterian Church's constitution, which required all

doctrinal changes be approved by the presbyteries. While some members of

the church could regard the Five Fundamentals as a satisfactory

explanation of Scriptures and the Confession, there were others who

could not, and therefore, the Presbyteries should be free to hold to

whatever theories they saw fit in interpreting Scripture and the

Confession.

The Auburn Affirmation was circulated beginning in November 1923

and ultimately signed by 174 clergymen. In January 1924, it was released

to the press, along with the names of 150 signatories.

The General Assembly of 1924

Conservative activities prior to the 1924 General Assembly

The

most significant conservative preparation for the General Assembly of

1924 actually occurred slightly before the 1923 General Assembly. This

was the publication of J. Gresham Machen's Christianity and Liberalism.

In this book, Machen argued that liberalism, far from being a set of

teachings that could be accommodated within the church, was in fact

antithetical to the principles of Christianity and was currently engaged

in a struggle against historic Christianity.

Liberal activities prior to the 1924 General Assembly

New

York Presbytery, which had been ordered by General Assembly to deal

with Fosdick, adopted a report that essentially exonerated Fosdick of

any wrongdoing.

In June 1923, New York Presbytery ordained two men—Henry P. Van

Dusen and Cedric O. Lehman — who refused to affirm the virgin birth.

On December 31, 1923, Henry van Dyke publicly relinquished his

pew at First Presbyterian Church, Princeton as a protest against

Machen's fundamentalist preaching. Van Dyke would ultimately return to

his pew in December 1924 when Charles Erdman replaced Machen in the

pulpit.

In May 1924, the Auburn Affirmation was republished, along with supplementary materials, and now listing 1,274 signatories.

Convening the Assembly

General Assembly met in Grand Rapids, Michigan

in May 1924. During the campaign for moderator, William Jennings Bryan

threw his weight behind Clarence E. Macartney (the Philadelphia minister

who was instrumental in bringing charges against Fosdick), who narrowly

beat out moderate Princeton Theological Seminary faculty member Charles

Erdman by a vote of 464–446. Macartney named Bryan his vice-moderator.

No action was taken at this General Assembly about the Auburn

Affirmation. The ordination of Van Dusen and Lehman was referred to the

Synod of New York for "appropriate action."

On the question of Harry Fosdick, moderates in 1924 steered

debate away from his theology and towards matter of polity. As Fosdick

was a Baptist, General Assembly instructed First Presbyterian Church,

New York to invite Fosdick to join the Presbyterian Church, and if he

would not, to get rid of him. Fosdick refused to join the Presbyterian

Church and ultimately resigned from his post at First Presbyterian

Church in October.

The General Assembly of 1925

Henry Sloane Coffin (1877–1954) on the cover of Time magazine.

At the 1925 General Assembly, held in Columbus, Ohio,

the denomination seemed determined to put the Fosdick controversy

behind them. Charles R. Erdman was elected as moderator, which was

widely seen as a blow against the fundamentalists. Erdman, a professor

at Princeton Theological Seminary, had been engaged in a series of

debates with J. Gresham Machen and Clarence Macartney throughout the

year, and in spring 1925, he was ousted as Princeton Seminary's student

advisor for being insufficiently enthusiastic about the League of

Evangelical Students, set up as a counterweight to more liberal

intervarsity organizations. Erdman was himself theologically

conservative, but was more concerned with pursuing "purity and peace and

progress" (his slogan during the election for moderator) than he was

with combatting liberalism. Machen felt that men like Erdman would

ultimately be responsible for agnostic Modernism triumphing in the

Presbyterian Church.

It seemed to many observers that the licensing of Van Dusen and

Lehman was likely to cause a split in the church. General Assembly

required all candidates to the ministry to affirm the virgin birth and

returned the matter to New York Presbytery for proper proceedings. In

response, the New York commissioners, led by Henry Sloane Coffin

protested that General Assembly had no right to change or add to the

conditions for entrance to the ministry beyond those affirmed in the

reunions of 1870 and 1906. Coffin and the liberals were prepared to walk

out of the Assembly and take their churches out of the denomination

rather than submit to the further "Bryanizing of the Presbyterian

Church." A special commission of fifteen was appointed to study the

constitutional issues involved. Erdman was able to convince Coffin not

to leave the denomination, arguing that, as his interpretation of the

constitution was the correct one, he would prevail when the Special

Commission issued its report.

The Scopes Trial (1925)

At the same time he had been campaigning against Darwinism (largely

unsuccessfully) within the Presbyterian Church, William Jennings Bryan

had also been encouraging state lawmakers to pass laws banning the

teaching of evolution in public schools. Several states had responded to

Bryan's call, including Tennessee, which passed such a law in March 1925. (Given the present-day contours of the evolution-creation debate,

In many states in 1925, evolution continued to be taught in church-run

institutions at the same time that its teaching was banned in state-run

public schools.)

The ACLU was seeking a test case to challenge these anti-evolutionary laws. This led to the famous trial of John Scopes for teaching evolution in a public school in Dayton, Tennessee. The ACLU sent in renowned lawyer John Randolph Neal, Jr. to defend Scopes.

Baptist pastor William Bell Riley, founder and president of the World Christian Fundamentals Association,

persuaded William Jennings Bryan to act as its counsel. Bryan invited

his major allies in the Presbyterian General Assembly to attend the

trial with him, but J. Gresham Machen refused to testify, saying he had

not studied biology in enough detail to testify at trial, while Clarence

Macartney had a previous engagement.

In response to the announcement that Bryan would be attending the trial,

renowned lawyer and committed agnostic Clarence Darrow volunteered to serve on Scopes' defense team.

The stage was thus set for a trial which would prove to be a media circus, with reporters from across the country descending on the small town of 1,900 people.

Although the prosecution of Scopes was successful, the trial is

widely seen as a crucial moment in discrediting the fundamentalist

movement in America, particularly after Darrow called Bryan to the stand

and he appeared little able to defend his view of the Bible.

Among the media, Bryan's loudest and ultimately most influential critic was H. L. Mencken, who reported on the trial in his columns and denounced fundamentalism as irrational, backwards and intolerant.

As noted earlier, opposition to Darwinism was always much more

important to Bryan than it was to other conservative Presbyterian Church

leaders. Thus, following Bryan's death in 1925, the debate about

evolution, while it remained an issue within church politics, never

again assumed the prominence to the debate that it had while Bryan was

alive. (Probably the reason why the issue of evolution has obtained such

an iconic status within the popular consciousness about the

Fundamentalist–Modernist Controversy is that it represented the one

point where internal church politics intersected with government,

specifically public school, policy.)

The Special Commission of 1925 and the General Assembly of 1926

The

Special Committee appointed at the General Assembly of 1925 consisted

mainly of moderates. The committee solicited testimony from both sides,

and received statements from Machen, Macartney, and Coffin.

At the 1926 General Assembly, another moderate, W.O. Thompson, was elected as moderator.

The Special Committee delivered its report on May 28. It argued

that there were five major causes of unrest in the Presbyterian Church:

1) general intellectual movements, including "the so-called conflict

between science and religion", naturalistic worldviews, different

understandings of the nature of God, and changes in language; 2)

historical differences going back to the Old School-New School split; 3)

disagreements about church polity, particularly the role of General

Assembly, and lack of representation of women in the church; 4)

theological changes; and 5) misunderstanding. The report went on to

conclude that the Presbyterian system had traditionally allowed a

diversity of views when the core of truth was identical; and that the

church flourished when it focused on its unity of spirit. Toleration of

doctrinal diversity, including in how to interpret the Westminster

Confession, was to be encouraged. In short, the report essentially

affirmed the views of the Auburn Affirmation. The committee affirmed

that General Assembly could not amend the Westminster Confession without

the permission of the presbyteries, though it could issue judicial

rulings consistent with the Confession that were binding on the

presbyteries. The Five Fundamentals, though, had no binding authority.

In spite of Clarence Macartney's opposition on the floor of General Assembly, the committee's report was adopted.

The Battle for Princeton Theological Seminary, 1926–29

Following

the reunion of the Old School and New School in 1870, Princeton

Theological Seminary remained the bulwark of Old School thought within

the Presbyterian Church. Indeed, by 1920, it was arguably the only

remaining Old School institution in the Presbyterian Church.

The majority of the faculty in 1920 remained convinced Old Schoolers, including J. Gresham Machen and Geerhardus Vos. However, to combat a perceived lack of training in practical divinity,

a number of more moderate New Schoolers were brought in, including

Charles Erdman and J. Ross Stevenson, who by 1920 was the president of

the seminary. As we saw above, the tension between Old Schoolers and

moderates revealed itself in debates about the proposed Church Union of

1920; Machen's anti-liberal preaching which resulted in the public

fall-out with Harry van Dyke; the controversy about Erdman's approach to

the League of Evangelical Students; and splits about how to deal with

the splits in the wider church.

By 1925, the Old School's majority on the faculty was threatened,

but the selection of Clarence Macartney to replace outgoing Professor

of Apologetics

William Greene seemed to solidify the Old School majority on the

faculty. However, when Macartney turned the job down, Machen was offered

the job.

Before he could accept or refuse, however, General Assembly

intervened, and in the 1926 General Assembly, moderates succeeded in

securing a committee to study how to reconcile the two parties at

Princeton. (The seminary was governed by a board of directors subject to

the supervision of General Assembly.) (On a sidenote, some members of

the General Assembly seem to have been wary of Machen because of his

opposition to Prohibition.)

The committee reported back at the General Assembly of 1927,

where the moderate Robert E. Speer was elected as moderator. Their

report concluded that the source of the difficulties at Princeton was

that some of the Princeton faculty (i.e. Machen) were trying to keep

Princeton in the service of a certain party in the church rather than

doing what was in the best interest of the denomination as a whole. They

recommended re-organization of the seminary. General Assembly renewed

the committee's mandate and ordered them to study how to re-organize the

seminary.

This led Machen to declare that the 1927 General Assembly was

"probably the most disastrous meeting, from the point of view of

evangelical Christianity, that has been held in the whole history of our

Church." Machen composed and had circulated in the denomination a

document entitled "The Attack Upon Princeton Seminary: A Plea for Fair

Play." He argued that Princeton was the only seminary continuing to

defend orthodoxy among the older theological institutions in the

English-speaking world. The loss of the seminary would be a major blow

for orthodoxy. The moderates and liberals already had control of pretty

much every seminary in the denomination: why couldn't the conservatives

be left with one?

The committee reported to the 1928 General Assembly, held in Tulsa, Oklahoma,

recommending re-organizing the seminary to give more powers to the

president of the seminary and to replace the two ruling boards with one

unified board. In response, Clarence Macartney responded that his party

were prepared to take legal action to stop this from happening. Wary,

General Assembly simply appointed a committee to continue studying the

matter.

This committee reported to the 1929 General Assembly. Machen gave

a fiery speech on the floor of General Assembly, but he could not

prevent General Assembly from voting to re-organize the seminary.

Rather than contesting this decision in the courts as had been

threatened, Machen now decided to set up a new seminary to be a bastion

of conservative thought. This institution would become Westminster Theological Seminary

(named to stress its fidelity to the Westminster Confession of Faith)

and several conservatives on the Princeton faculty, including Machen, Cornelius Van Til, Robert Dick Wilson, and Oswald Thompson Allis,

would leave Princeton to teach at Westminster. Clarence Macartney

initially opposed setting up Westminster, arguing that conservatives

should stay at Princeton where they could continue to provide an

orthodox voice. Machen responded that Princeton was in a state of apostasy and that he couldn't serve alongside apostates. Macartney was eventually won over to Machen's side.

Foreign missions, 1930–36

John D. Rockefeller, Jr. (1874–1960).

In 1930, as a result of widespread second thoughts about missions in general, a group of Baptist laymen at the request of John D. Rockefeller, Jr.

concluded that it was time for a serious re-evaluation of the

effectiveness of foreign missions. With Rockefeller's financial backing,

they convinced seven major denominations – the Methodist Episcopal Church, the Northern Baptist Convention, the Reformed Church in America, the Congregational church, the Episcopal Church in the United States of America, the Presbyterian Church in the United States of America and the United Presbyterian Church of North America – to participate in their "Laymen's Foreign Missions Inquiry". They commissioned a study of missionaries in India, Burma, China, and Japan and launched a separate inquiry under the chairmanship of the philosopher and Harvard professor William Ernest Hocking. These two inquiries led to the publication of a one-volume summary of the findings of the Laymen's Inquiry entitled Re-Thinking Missions: A Laymen's Inquiry after One Hundred Years in 1932.

Re-Thinking Missions argued that in the face of emerging secularism, Christians should ally with other world religions, rather than struggle against them.

The seven denominations who had agreed to participate in the Laymen's Inquiry now distanced themselves from the report. The Presbyterian Board of Foreign Missions

issued a statement reaffirming the board's commitment to the

evangelistic basis of the missionary enterprise and to Jesus Christ as

the only Lord and Savior.

Pearl S. Buck (1892–1973).

Pearl S. Buck now weighed into the debate. In a review published in The Christian Century, she praised the report, saying it should be read by every Christian in America and, ironically mimicking the biblical literalism

of the fundamentalists, "I think this is the only book I have ever read

that seems to me literally true in its every observation and right in

its every conclusion." Then, in a November 1932 speech before a large audience at the Astor Hotel, later published in Harper's,

Buck decried gauging the success of missions by the numbers of new

church members. Instead she advocated humanitarian efforts to improve

the agricultural, educational, medical, and sanitary conditions of the

community. She described the typical missionary as "narrow, uncharitable, unappreciative, ignorant." In the Harpers article along with another in Cosmopolitan published in May 1933, Buck rejected the doctrine of original sin, saying "I believe that most of us start out wanting to do right and to be good." She asserted that belief in the virgin birth or the divinity of Christ

was not a prerequisite to being a Christian. She said that the only

need is to acknowledge that one can't live without Christ and to reflect

that in one's life.

Macartney quickly called on the Board of Foreign Missions, under the presidency of Charles Erdman, to denounce Re-Thinking Missions

and asked for their response to Buck's statements. Erdman responded

that the Board was committed to historic evangelical standards and that

they felt that Pearl S. Buck's comments were unfortunate, but he hoped

she might yet be won back to the missionary cause. She would eventually

resign as a Presbyterian missionary in May.

J. Gresham Machen now published a book arguing that the Board of

Foreign Missions was insufficiently evangelical and particularly that

its secretary, Robert E. Speer, had refused to require missionaries to

subscribe to the Five Fundamentals. In New Brunswick Presbytery, Machen

proposed an overture to General Assembly calling on it to ensure that in

future, only solidly evangelical Christians be appointed to the Board

of Foreign Missions. Machen and Speer faced off in the Presbytery, with

Speer arguing that conflict and division were bad for the church — the

presbytery agreed and refused to make the recommendation.

Clarence Macartney, however, was able to get a similar motion

through the Presbytery of Philadelphia, so the issue came before the

General Assembly of 1933. The majority report of the Standing Committee

of Foreign Missions affirmed the church's adherence to the Westminster Confession; expressed its confidence that Speer and the Board shared this conviction; and repudiated Re-Thinking Missions.

The minority report argued that the Board was not orthodox and proposed

a slate of conservatives candidates for the Board. The majority report

passed overwhelmingly.

Creation of the Independent Board for Presbyterian Foreign Missions

Disapproving of General Assembly's decision not to appoint a new slate of conservatives to the Board of Foreign Missions, J. Gresham Machen, along with H. McAllister Griffiths, announced that they were forming an Independent Board for Presbyterian Foreign Missions

to truly promote biblical and Presbyterian work. Macartney refused to

go along with Machen in setting up an independent missions board.

The 1934 General Assembly declared that the Independent Board

violated the Presbyterian constitution and ordered the Board to cease

collecting funds within the church and ordered all Presbyterian clergy

and laity to sever their connections with the Board or face disciplinary

action. (This motion was opposed by both Macartney and Henry Sloane Coffin

as overly harsh.) Less than a month later, New Brunswick Presbytery

asked Machen for his response. He replied that General Assembly's

actions were illegal and that he would not shut down the Independent

Board. The presbytery consequently brought charges against Machen

including violation of his ordination vows and renouncing the authority

of the church. A trial was held, and in March 1935, he was convicted and

suspended from the ministry.

Macartney urged Machen to compromise, but he refused. In June

1935, he set up the Presbyterian Constitutional Covenant Union. In

October, the split between Macartney and Machen spread to Westminster

Seminary, where the faculty, led by Machen, called on the board of

trustees to announce their support of the Independent Board of Foreign

Missions and the Covenant Union. Thirteen trustees, including Macartney,

refused to do so and resigned in 1936.

Eight ministers, including Machen, were tried in the General

Assembly of 1936. They were convicted and removed from the ministry.

Machen then led the Presbyterian Constitutional Covenant Union to form a

new denomination, the Presbyterian Church of America, later forced to

change its name to the Orthodox Presbyterian Church in 1939.

Legacy

As a

result of the departure of Machen and the denominational conservatives,

especially of the Old School, the shape of the Presbyterian Church in

the USA as a modernist, liberal denomination was secured. The PCUSA

would eventually merge with the United Presbyterian Church of North America in 1958 to form the United Presbyterian Church in the United States of America and in 1983, the UPCUSA would merge with the Presbyterian Church in the United States (the "Southern Presbyterians" who had split with the PCUSA in 1861 due to the Civil War) to form the current Presbyterian Church (USA).

The dispute between the fundamentalists and modernists would be

played out in nearly every Christian denomination. By the 1920s, it was

clear that every mainstream Protestant denomination was going to be

willing to accommodate modernism, with the exception of the

Presbyterians and Southern Baptists, where it was still unclear. When

the outcome of the Fundamentalist–Modernist Controversy brought the

Presbyterians into the camp willing to accommodate modernism, this left

the Southern Baptists

as the only mainstream denomination where fundamentalists were still

active within the denomination. Fundamentalists and modernists would

continue to struggle within the Southern Baptist Convention and the

triumph of fundamentalist views in that denomination would not be secure

until the Southern Baptist Convention conservative resurgence of 1979–1990.

The social tensions and prejudices created by the

Fundamentalist-Modernist split would remain very active within American

Christianity into the twenty-first century, with modernists seeing fundamentalists

as intolerant, and fundamentalists seeing modernists as overly willing

to compromise with the forces of secularism, abandoning authentic

Christianity in the process.