Marco Polo

| |

|---|---|

Polo wearing a Tartar outfit, date of print unknown

| |

| Born | 1254 |

| Died | 8 January 1324 (aged 69–70) |

| Resting place | Church of San Lorenzo 45.4373°N 12.3455°E |

| Nationality | Italian |

| Occupation | Merchant, explorer, writer |

| Known for | The Travels of Marco Polo |

| Spouse(s) | Donata Badoer |

| Children | Fantina, Bellela and Moretta |

| Parent(s) |

|

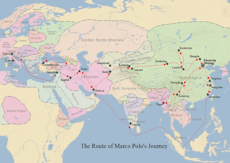

Marco Polo, Venice; 1254 – January 8–9, Venice, 1324) was an Italian merchant, explorer, and writer who travelled through Asia along the Silk Road between 1271 and 1295. His travels are recorded in The Travels of Marco Polo (also known as Book of the Marvels of the World and Il Milione, c. 1300), a book that described to Europeans the then mysterious culture and inner workings of the Eastern world, including the wealth and great size of China and its capital Peking, giving their first comprehensive look into China, India, Japan and other Asian cities and countries.

Born in Venice, Marco learned the mercantile trade from his father and his uncle, Niccolò and Maffeo, who travelled through Asia and met Kublai Khan. In 1269, they returned to Venice to meet Marco for the first time. The three of them embarked on an epic journey to Asia, exploring many places along the Silk Road until they reached Cathay (China). They were received by the royal court of Kublai Khan, who was impressed by Marco's intelligence and humility. Marco was appointed to serve as Khan's foreign emissary to India and Burma, and he was sent on many diplomatic missions throughout the empire. As part of this appointment, Marco also traveled extensively inside China, living in the emperor's lands for 17 years and seeing many things that had previously been unknown to Europeans. Around 1292, the Polos also offered to accompany the Mongol princess Kököchin in Persia, arriving around the following two years. After leaving the princess, they travelled overland to Constantinople and then to Venice, returning home after 24 years. At this time, Venice was at war with Genoa; Marco was imprisoned and dictated his stories to Rustichello da Pisa, a cellmate. He was released in 1299, became a wealthy merchant, married, and had three children. He died in 1324 and was buried in the church of San Lorenzo in Venice.

Though he was not the first European to reach China, Marco Polo was the first to leave a detailed chronicle of his experience. This book inspired Christopher Columbus and many other travellers. There is substantial literature based on Polo's writings; he also influenced European cartography, leading to the introduction of the Fra Mauro map.

Life

Birthplace and family origin

XVI century portrait of Marco Polo

Marco Polo was born around 1254 in Venice, capital of the Venetian Republic. His father, Niccolò Polo, had his houselod in Venice and left Marco's mother pregnant in order to travel to Asia with his brother Maffeo Polo. Their return to Italy in order to go to Venice and visit their household is described in the Travels of Marco Polo as follows: they

departed from Acre and went to Negropont, and from Negropont they

continued their voyage to Venice. On their arrival there, Messer Nicolas

found that his wife was dead, and that she had left behind her a son of

fifteen years of age, whose name was Marco.

His first known ancestor was a great uncle, Marco Polo (the older) from Venice, who lent some money and commanded a ship in Costantinople. Andrea, Marco's grandfather, lived in Venice in "contrada San Felice", he had three sons: Marco "the older", Matteo e Niccolò (Marco's father). Some old Venetian historical sources considered Polo's ancestors to be of far Dalmatian origin.

Nickname Milione

Corte Seconda del Milion is still named after the nickname of Polo, Il Milione

Marco Polo is most often mentioned in the archives of the Republic of Venice as Marco Paulo de confinio Sancti Iohannis Grisostomi, which means Marco Polo of the contrada of St John Chrysostom Church.

However, he was also nicknamed Milione during his lifetime. In fact, the Italian title of his book was Il libro di Marco Polo detto il Milione, which means "The Book of Marco Polo, nicknamed 'Milione'".

According to the 15th-century humanist Giovan Battista Ramusio,

his fellow citizens awarded him this nickname when he came back to

Venice, because he kept on saying that Kublai Khan's wealth was counting

in millions. More precisely, he was nicknamed Messer Marco Milioni (Mr Marco Millions).

However, since also his father Niccolò was nicknamed Milione, 19th-century philologist Luigi Foscolo Benedetto was persuaded that Milione was a shortened version of Emilione, and that this nickname was used to distinguish Niccolò's and Marco's branch from other Polo families.

Early life and Asian travel

Mosaic of Marco Polo displayed in the Palazzo Doria-Tursi, in Genoa, Italy

In 1168, his great-uncle, Marco Polo, borrowed money and commanded a ship in Constantinople.

His grandfather, Andrea Polo of the parish of San Felice, had three

sons, Maffeo, yet another Marco, and the traveller's father Niccolò. This genealogy, described by Ramusio, is not universally accepted as there is no additional evidence to support it.

His father, Niccolò Polo, a merchant, traded with the Near East, becoming wealthy and achieving great prestige. Niccolò and his brother Maffeo set off on a trading voyage before Marco's birth. In 1260, Niccolò and Maffeo, while residing in Constantinople, then the capital of the Latin Empire, foresaw a political change; they liquidated their assets into jewels and moved away. According to The Travels of Marco Polo, they passed through much of Asia, and met with Kublai Khan, a Mongol ruler and founder of the Yuan dynasty. Their decision to leave Constantinople proved timely. In 1261 Michael VIII Palaiologos, the ruler of the Empire of Nicaea, took Constantinople, promptly burned the Venetian quarter and re-established the Eastern Roman Empire. Captured Venetian citizens were blinded,[29]

while many of those who managed to escape perished aboard overloaded

refugee ships fleeing to other Venetian colonies in the Aegean Sea.

Almost nothing is known about the childhood of Marco Polo until

he was fifteen years old, excepting that he probably spent part of his

childhood in Venice. Meanwhile, Marco Polo's mother died, and an aunt and uncle raised him.

He received a good education, learning mercantile subjects including

foreign currency, appraising, and the handling of cargo ships; he learned little or no Latin. His father later married Floradise Polo (née Trevisan).

In 1269, Niccolò and Maffeo returned to their families in Venice, meeting young Marco for the first time. In 1271, during the rule of Doge Lorenzo Tiepolo,

Marco Polo (at seventeen years of age), his father, and his uncle set

off for Asia on the series of adventures that Marco later documented in

his book.

They sailed to Acre and later rode on their camels to the Persian

port Hormuz. During the first stages of the journey, they stayed for a

few months in Acre and were able to speak with Archdeacon Tedaldo Visconti of Piacenza.

The Polo family, on that occasion, had expressed their regret at the

long lack of a pope, because on their previous trip to China they had

received a letter from Kublai Khan to the Pope, and had thus had to

leave for China disappointed. During the trip, however, they received

news that after 33 months of vacation, finally the Conclave

had elected the new Pope and that he was... the archdeacon of Acre! The

three of them hurried to return to the Holy Land, where the new Pope

entrusted them with letters for the "Great Khan", inviting him to send

his emissaries to Rome. To give more weight to this mission, he sent

with the Pole, as his legates, two Dominican fathers, Guglielmo of

Tripoli and Nicola of Piacenza.

They continued overland until they get to Kublai Khan's place in Shangdu, China (known as Cathay). By this time, Marco was 21 years old.

Impressed by Marco's intelligence and humility, Khan appointed him to

serve as his foreign emissary to India and Burma. He was sent on many

diplomatic missions throughout his empire, but also entertained the Khan

with stories and observations about the lands he saw. As part of this

appointment, Marco traveled extensively inside China, living in the

emperor's lands for 17 years.

Kublai initially refused several times to let the Polos return to

Europe, as he appreciated their company and they became useful to him. However, around 1291, he finally granted permission, entrusting the Polos with his last duty: accompany the Mongol princess Kököchin, who was to become the consort of Arghun Khan, in Persia. After leaving the princess, the Polos travelled overland to Constantinople. They later decided to return to their home.

They returned to Venice in 1295, after 24 years, with many riches

and treasures. They had travelled almost 15,000 miles (24,000 km).

Genoese captivity and later life

Marco Polo returned to Venice in 1295 with his fortune converted into gemstones. At this time, Venice was at war with the Republic of Genoa. Polo armed a galley equipped with a trebuchet to join the war. He was probably caught by Genoans in a skirmish in 1296, off the Anatolian coast between Adana and the Gulf of Alexandretta and not during the battle of Curzola (September 1298), off the Dalmatian coast. The latter claim is due to a later tradition (16th century) recorded by Giovanni Battista Ramusio.

He spent several months of his imprisonment dictating a detailed account of his travels to a fellow inmate, Rustichello da Pisa,

who incorporated tales of his own as well as other collected anecdotes

and current affairs from China. The book soon spread throughout Europe

in manuscript form, and became known as The Travels of Marco Polo.

It depicts the Polos' journeys throughout Asia, giving Europeans their

first comprehensive look into the inner workings of the Far East,

including China, India, and Japan.

Polo was finally released from captivity in August 1299, and returned home to Venice, where his father and uncle in the meantime had purchased a large palazzo in the zone named contrada San Giovanni Crisostomo (Corte del Milion). For such a venture, the Polo family probably invested profits from trading, and even many gemstones they brought from the East.

The company continued its activities and Marco soon became a wealthy

merchant. Marco and his uncle Maffeo financed other expeditions, but

likely never left Venetian provinces, nor returned to the Silk Road and Asia. Sometime before 1300, his father Niccolò died. In 1300, he married Donata Badoèr, the daughter of Vitale Badoèr, a merchant. They had three daughters, Fantina (married Marco Bragadin), Bellela (married Bertuccio Querini), and Moreta.

Pietro d'Abano, philosopher, doctor and astrologer

Pietro d'Abano philosopher, doctor and astrologer based in Padua,

reports having spoken with Marco Polo about what he had observed in the

vault of the sky during his travels. Marco told him that during his

return trip to the South China Sea, he had spotted what he describes in a drawing as a star "shaped like a sack" (ut sacco) with a big tail (magna habens caudam), most likely a comet.

Astronomers agree that there were no comets sighted in Europe at the

end of 1200, but there are records about a comet sighted in China and

Indonesia in 1293. Interestingly, this circumstance does not appear in Polo's book of Travels.

Peter D'Abano kept the drawing in his volume "Conciliator

Differentiarum, quæ inter Philosophos et Medicos Versantur". Marco Polo

gave Pietro other astronomical observations he made in the Southern Hemisphere, and also a description of the Sumatran rhinoceros, which are collected in the Conciliator.

In 1305 he is mentioned in a Venetian document among local sea captains regarding the payment of taxes.

His relation with a certain Marco Polo, who in 1300 was mentioned with

riots against the aristocratic government, and escaped the death

penalty, as well as riots from 1310 led by Bajamonte Tiepolo and Marco Querini, among whose rebels were Jacobello and Francesco Polo from another family branch, is unclear.

Polo is clearly mentioned again after 1305 in Maffeo's testament from

1309–1310, in a 1319 document according to which he became owner of some

estates of his deceased father, and in 1321, when he bought part of the

family property of his wife Donata.

Death

San Lorenzo church in the sestiere of Castello (Venice), where Polo was buried. The photo shows the church as is today, after the 1592 rebuilding.

Plaque on Teatro Malibran, which was build upon Marco Polo's house

In 1323, Polo was confined to bed, due to illness. On January 8, 1324, despite physicians' efforts to treat him, Polo was on his deathbed.

To write and certify the will, his family requested Giovanni

Giustiniani, a priest of San Procolo. His wife, Donata, and his three

daughters were appointed by him as co-executrices.

The church was entitled by law to a portion of his estate; he approved

of this and ordered that a further sum be paid to the convent of San Lorenzo, the place where he wished to be buried. He also set free Peter, a Tartar servant, who may have accompanied him from Asia, and to whom Polo bequeathed 100 lire of Venetian denari.

He divided up the rest of his assets, including several

properties, among individuals, religious institutions, and every guild

and fraternity to which he belonged. He also wrote off multiple debts including 300 lire that his sister-in-law owed him, and others for the convent of San Giovanni, San Paolo of the Order of Preachers, and a cleric named Friar Benvenuto. He ordered 220 soldi be paid to Giovanni Giustiniani for his work as a notary and his prayers.

The will was not signed by Polo, but was validated by the then-relevant "signum manus" rule, by which the testator only had to touch the document to make it legally valid.

Due to the Venetian law stating that the day ends at sunset, the exact

date of Marco Polo's death cannot be determined, but according to some

scholars it was between the sunsets of January 8 and 9, 1324. Biblioteca Marciana,

which holds the original copy of his testament, dates the testament in

January 9, 1323, and gives the date of his death at some time in June

1324.

Travels of Marco Polo

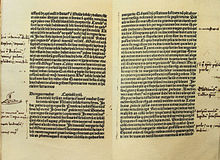

An authoritative version of Marco Polo's book does not and cannot

exist, for the early manuscripts differ significantly, and the

reconstruction of the original text is a matter of textual criticism. A total of about 150 copies in various languages are known to exist. Before availability of printing press, errors were frequently made during copying and translating, so there are many differences between the various copies.

Polo related his memoirs orally to Rustichello da Pisa while both were prisoners of the Genova Republic. Rustichello wrote Devisement du Monde in Franco-Venetian. The idea probably was to create a handbook for merchants, essentially a text on weights, measures and distances.

The oldest surviving manuscript is in Old French heavily flavoured with Italian;

According to the Italian scholar Luigi Foscolo Benedetto, this "F" text

is the basic original text, which he corrected by comparing it with the

somewhat more detailed Italian of Giovanni Battista Ramusio, together with a Latin manuscript in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana.

Other early important sources are R (Ramusio's Italian translation

first printed in 1559), and Z (a fifteenth-century Latin manuscript kept

at Toledo, Spain). Another Old French Polo manuscript, dating to around

1350, is held by the National Library of Sweden.

One of the early manuscripts Iter Marci Pauli Veneti was a translation into Latin made by the Dominican brother Francesco Pipino

in 1302, just a few years after Marco's return to Venice. Since Latin

was then the most widespread and authoritative language of culture, it

is suggested that Rustichello's text was translated into Latin for a

precise will of the Dominican Order, and this helped to promote the book on a European scale.

The first English translation is the Elizabethan version by John Frampton published in 1579, The most noble and famous travels of Marco Polo, based on Santaella's Castilian translation of 1503 (the first version in that language).

The published editions of Polo's book rely on single manuscripts,

blend multiple versions together, or add notes to clarify, for example

in the English translation by Henry Yule. The 1938 English translation by A.C. Moule and Paul Pelliot is based on a Latin manuscript found in the library of the Cathedral of Toledo in 1932, and is 50% longer than other versions. The popular translation published by Penguin Books in 1958 by R. E. Latham works several texts together to make a readable whole.

Narrative

Statue of Marco Polo in Hangzhou, China

The book opens with a preface describing his father and uncle traveling to Bolghar where Prince Berke Khan lived. A year later, they went to Ukek and continued to Bukhara. There, an envoy from the Levant invited them to meet Kublai Khan, who had never met Europeans. In 1266, they reached the seat of Kublai Khan at Dadu, present day Beijing,

China. Kublai received the brothers with hospitality and asked them

many questions regarding the European legal and political system. He also inquired about the Pope and Church in Rome.

After the brothers answered the questions he tasked them with

delivering a letter to the Pope, requesting 100 Christians acquainted

with the Seven Arts (grammar, rhetoric, logic, geometry, arithmetic, music and astronomy). Kublai Khan requested that an envoy bring him back oil of the lamp in Jerusalem. The long sede vacante between the death of Pope Clement IV

in 1268 and the election of his successor delayed the Polos in

fulfilling Kublai's request. They followed the suggestion of Theobald

Visconti, then papal legate for the realm of Egypt,

and returned to Venice in 1269 or 1270 to await the nomination of the

new Pope, which allowed Marco to see his father for the first time, at

the age of fifteen or sixteen.

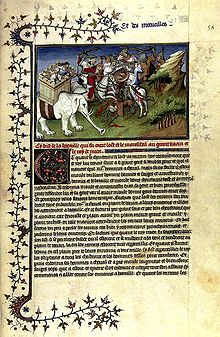

Polo meeting Kublai Khan.

In 1271, Niccolò, Maffeo and Marco Polo embarked on their voyage to fulfil Kublai's request. They sailed to Acre, and then rode on camels to the Persian port of Hormuz. The Polos wanted to sail straight into China, but the ships there were not seaworthy, so they continued overland through the Silk Road, until reaching Kublai's summer palace in Shangdu, near present-day Zhangjiakou.

In one instance during their trip, the Polos joined a caravan of

travelling merchants whom they crossed paths with. Unfortunately, the

party was soon attacked by bandits,

who used the cover of a sandstorm to ambush them. The Polos managed to

fight and escape through a nearby town, but many members of the caravan

were killed or enslaved.

Three and a half years after leaving Venice, when Marco was about 21

years old, the Polos were welcomed by Kublai into his palace. The exact date of their arrival is unknown, but scholars estimate it to be between 1271 and 1275. On reaching the Yuan court, the Polos presented the sacred oil from Jerusalem and the papal letters to their patron.

Marco knew four languages, and the family had accumulated a great

deal of knowledge and experience that was useful to Kublai. It is

possible that he became a government official; he wrote about many imperial visits to China's southern and eastern provinces, the far south and Burma.

They were highly respected and sought after in the Mongolian court, and

so Kublai Khan decided to decline the Polos' requests to leave China.

They became worried about returning home safely, believing that if

Kublai died, his enemies might turn against them because of their close

involvement with the ruler. In 1292, Kublai's great-nephew, then ruler

of Persia,

sent representatives to China in search of a potential wife, and they

asked the Polos to accompany them, so they were permitted to return to

Persia with the wedding party—which left that same year from Zaitun in southern China on a fleet of 14 junks. The party sailed to the port of Singapore, travelled north to Sumatra, and sailed west to the Point Pedro port of Jaffna under Savakanmaindan and to Pandyan of Tamilakkam. Eventually Polo crossed the Arabian Sea to Hormuz.

The two-year voyage was a perilous one—of the six hundred people (not

including the crew) in the convoy only eighteen had survived (including

all three Polos). The Polos left the wedding party after reaching Hormuz and travelled overland to the port of Trebizond on the Black Sea, the present day Trabzon.

A page from Il Milione, from a manuscript believed to date between 1298–1299.

Role of Rustichello

The British scholar Ronald Latham has pointed out that The Book of Marvels was in fact a collaboration written in 1298–1299 between Polo and a professional writer of romances, Rustichello of Pisa. It is believed that Polo related his memoirs orally to Rustichello da Pisa while both were prisoners of the Genova Republic. Rustichello wrote Devisement du Monde in Franco-Venetian language,

which was the language of culture widespread in northern Italy between

the subalpine belt and the lower Po between the 13th and 15th centuries.

Latham also argued that Rustichello may have glamorised Polo's

accounts, and added fantastic and romantic elements that made the book a

bestseller.

The Italian scholar Luigi Foscolo Benedetto had previously demonstrated

that the book was written in the same "leisurely, conversational style"

that characterised Rustichello's other works, and that some passages in

the book were taken verbatim or with minimal modifications from other

writings by Rustichello. For example, the opening introduction in The Book of Marvels to "emperors and kings, dukes and marquises" was lifted straight out of an Arthurian romance

Rustichello had written several years earlier, and the account of the

second meeting between Polo and Kublai Khan at the latter's court is

almost the same as that of the arrival of Tristan at the court of King Arthur at Camelot in that same book.

Latham believed that many elements of the book, such as legends of the

Middle East and mentions of exotic marvels, may have been the work of

Rustichello who was giving what medieval European readers expected to

find in a travel book.

Role of the Dominican Order

Apparently, from the very beginning Marco's story aroused contrasting

reactions, as it was received by some with a certain disbelief. The Dominican father Francesco Pipino was the author of a translation into Latin, Iter Marci Pauli Veneti

in 1302, just a few years after Marco's return to Venice. Francesco

Pipino solemnly affirmed the truthfulness of the book and defined Marco

as a "prudent, honoured and faithful man".

In his writings, the Dominican brother

Jacopo d'Acqui explains why his contemporaries were skeptical about

the content of the book. He also relates that before dying, Marco Polo

insisted that "he had told only a half of the things he had seen".

According to some recent research of the Italian scholar Antonio

Montefusco, the very close relationship that Marco Polo cultivated with

members of the Dominican Order

in Venice suggests that local fathers collaborated with him for a Latin

version of the book, which means that Rustichello's text was translated

into Latin for a precise will of the Order.

Since Dominican fathers had among their missions that of

evangelizing foreign peoples (cf. the role of Dominican missionaries in

China and in the Indies),

it is reasonable to think that they considered Marco's book as a

trustworthy piece of information for missions in the East. The

diplomatic communications between Pope Innocent IV and Pope Gregory X with the Mongols

were probably another reason for this endorsement. At the time, there

was open discussion of a possible Christian-Mongul alliance with an

anti-Islamic function. In fact, a mongol delegate was solemny baptised at the Second Council of Lyon. At the Council, Pope Gregory X promulgated a new Crusade to start in 1278 in liaison with the Mongols.

Authenticity and veracity

Kublai Khan's court, from French "Livre des merveilles"

Since its publication, some have viewed the book with skepticism.

Some in the Middle Ages regarded the book simply as a romance or fable,

due largely to the sharp difference of its descriptions of a

sophisticated civilisation in China to other early accounts by Giovanni da Pian del Carpine and William of Rubruck, who portrayed the Mongols as 'barbarians' who appeared to belong to 'some other world'.

Doubts have also been raised in later centuries about Marco Polo's

narrative of his travels in China, for example for his failure to

mention the Great Wall of China, and in particular the difficulties in

identifying many of the place names he used (the great majority, however, have since been identified).

Many have questioned if he had visited the places he mentioned in his

itinerary, if he had appropriated the accounts of his father and uncle

or other travelers, and some doubted if he even reached China, or that

if he did, perhaps never went beyond Khanbaliq (Beijing).

It has however been pointed out that Polo's accounts of China are

more accurate and detailed than other travelers' accounts of the

periods. Polo had at times refuted the 'marvelous' fables and legends

given in other European accounts, and despite some exaggerations and

errors, Polo's accounts have relatively few of the descriptions of

irrational marvels. In many cases where present (mostly given in the

first part before he reached China, such as mentions of Christian

miracles), he made a clear distinction that they are what he had heard

rather than what he had seen. It is also largely free of the gross

errors found in other accounts such as those given by the Moroccan

traveler Ibn Battuta who had confused the Yellow River with the Grand Canal and other waterways, and believed that porcelain was made from coal.

Modern studies have further shown that details given in Marco

Polo's book, such as the currencies used, salt productions and revenues,

are accurate and unique. Such detailed descriptions are not found in

other non-Chinese sources, and their accuracy is supported by

archaeological evidence as well as Chinese records compiled after Polo

had left China. His accounts are therefore unlikely to have been

obtained second hand. Other accounts have also been verified; for example, when visiting Zhenjiang in Jiangsu, China, Marco Polo noted that a large number of Christian churches had been built there. His claim is confirmed by a Chinese text of the 14th century explaining how a Sogdian named Mar-Sargis from Samarkand founded six Nestorian Christian churches there in addition to one in Hangzhou during the second half of the 13th century. His story of the princess Kököchin sent from China to Persia to marry the Īl-khān is also confirmed by independent sources in both Persia and China.

Birthplace controversy

According to some Croatian sources the exact date and place of birth are "archivally" unknown. The same sources also claimed Constantinople and the island of Curzola (today Korčula) as his possible birthplace. The lack of evidence makes the Curzola/Korčula theory (probably under Ramusio influence) as a specific birthplace strongly disputed. A scientific paper edited in 2013 states that "the story of the Korčulan origin of Marco Polo and/or his family can be approached as pure falsification or even as a theft of heritage... ".

Scholarly analyses

Text of the letter of Pope Innocent IV "to the ruler and people of the Tartars", brought to Güyüg Khan by John de Carpini, 1245

Seal of Güyük Khan using the classical Mongolian script, as found in a letter sent to the Roman Pope Innocent IV in 1246.

Letter from Arghun, Khan of the Mongol Ilkhanate, to Pope Nicholas IV, 1290.

Seal of the Mongol ruler Ghazan in a 1302 letter to Pope Boniface VIII, with an inscription in Chinese seal script

Explaining omissions

Skeptics have long wondered if Marco Polo wrote his book based on

hearsay, with some pointing to omissions about noteworthy practices and

structures of China as well as the lack of details on some places in his

book. While Polo describes paper money and the burning of coal, he fails to mention the Great Wall of China, tea, Chinese characters, chopsticks, or footbinding.

His failure to note the presence of the Great Wall of China was first

raised in the middle of seventeenth century, and in the middle of

eighteenth century, it was suggested that he might have never reached

China.

Later scholars such as John W. Haeger argued that Marco Polo might not

have visited Southern China due to the lack of details in his

description of southern Chinese cities compared to northern ones, while Herbert Franke

also raised the possibility that Marco Polo might not have been to

China at all, and wondered if he might have based his accounts on

Persian sources due to his use of Persian expressions. This is taken further by Dr. Frances Wood who claimed in her 1995 book Did Marco Polo Go to China? that at best Polo never went farther east than Persia (modern Iran), and that there is nothing in The Book of Marvels about China that could not be obtained via reading Persian books.

Wood maintains that it is more probable that Polo only went to

Constantinople (modern Istanbul, Turkey) and some of the Italian

merchant colonies around the Black Sea, picking hearsay from those

travellers who had been farther east.

Supporters of Polo's basic accuracy countered on the points

raised by skeptics such as footbinding and the Great Wall of China.

Historian Stephen G. Haw

argued that the Great Walls were built to keep out northern invaders,

whereas the ruling dynasty during Marco Polo's visit were those very

northern invaders. They note that the Great Wall familiar to us today is

a Ming structure built some two centuries after Marco Polo's travels; and that the Mongol

rulers whom Polo served controlled territories both north and south of

today's wall, and would have no reasons to maintain any fortifications

that may have remained there from the earlier dynasties. Other Europeans who travelled to Khanbaliq during the Yuan dynasty, such as Giovanni de' Marignolli and Odoric of Pordenone, said nothing about the wall either. The Muslim traveler Ibn Battuta,

who asked about the wall when he visited China during the Yuan dynasty,

could find no one who had either seen it or knew of anyone who had seen

it, suggesting that while ruins of the wall constructed in the earlier

periods might have existed, they were not significant or noteworthy at

that time.

Haw also argued that footbinding was not common even among

Chinese during Polo's time and almost unknown among the Mongols. While

the Italian missionary Odoric of Pordenone who visited Yuan

China mentioned footbinding (it is however unclear whether he was

merely relaying something he had heard as his description is

inaccurate), no other foreign visitors to Yuan

China mentioned the practice, perhaps an indication that the

footbinding was not widespread or was not practiced in an extreme form

at that time. Marco Polo himself noted (in the Toledo manuscript) the dainty walk of Chinese women who took very short steps.

It has also been noted by other scholars that many of the things not

mentioned by Marco Polo such as tea and chopsticks were not mentioned by

other travelers as well.

Haw also pointed out that despite the few omissions, Marco Polo's

account is more extensive, more accurate and more detailed than those of

other foreign travelers to China in this period. Marco Polo even observed Chinese nautical inventions such as the watertight compartments of bulkhead partitions in Chinese ships, knowledge of which he was keen to share with his fellow Venetians.

In addition to Haw, a number of other scholars have argued in

favor of the established view that Polo was in China in response to

Wood's book. Wood's book has been criticized by figures including Igor de Rachewiltz (translator and annotator of The Secret History of the Mongols) and Morris Rossabi (author of Kublai Khan: his life and times). The historian David Morgan points out basic errors made in Wood's book such as confusing the Liao dynasty with the Jin dynasty, and he found no compelling evidence in the book that would convince him that Marco Polo did not go to China. Haw also argues in his book Marco Polo's China

that Marco's account is much more correct and accurate than has often

been supposed and that it is extremely unlikely that he could have

obtained all the information in his book from second-hand sources.

Haw also criticizes Wood's approach to finding mention of Marco Polo in

Chinese texts by contending that contemporaneous Europeans had little

regard for using surnames and that a direct Chinese transliteration of the name "Marco" ignores the possibility of him taking on a Chinese or even Mongol name with no bearing or similarity with his Latin name.

Also in reply to Wood, Jørgen Jensen recalled the meeting of Marco Polo and Pietro d'Abano

in the late 13th century. During this meeting Marco gave to Pietro

details of the astronomical observations he had made on his journey.

These observations are only compatible with Marco's stay in China, Sumatra and the South China Sea and are recorded in Pietro's book Conciliator Differentiarum, but not in Marco's Book of Travels.

Reviewing Haw's book, Peter Jackson (author of The Mongols and the West) has said that Haw "must surely now have settled the controversy surrounding the historicity of Polo's visit to China".

Igor de Rachewiltz's review, which refutes Wood's points, concludes

with a strongly-worded condemnation: "I regret to say that F. W.'s book

falls short of the standard of scholarship that one would expect in a

work of this kind. Her book can only be described as deceptive, both in

relation to the author and to the public at large. Questions are posted

that, in the majority of cases, have already been answered

satisfactorily ... her attempt is unprofessional; she is poorly equipped

in the basic tools of the trade, i.e., adequate linguistic competence

and research methodology ... and her major arguments cannot withstand

close scrutiny. Her conclusion fails to consider all the evidence

supporting Marco Polo's credibility."

Exaggerations

Many scholars believe that Marco Polo exaggerated his importance in China. The British historian David Morgan thought that Polo had likely exaggerated and lied about his status in China, while Ronald Latham believed that such exaggerations were embellishments by his ghost writer Rustichello da Pisa. In The Book of Marvels, Polo claimed that he was a close friend and advisor to Kublai Khan and that he was the governor of the city of Yangzhou

for three years – yet no Chinese source mentions him as either a friend

of the Emperor or as the governor of Yangzhou – indeed no Chinese

source mentions Marco Polo at all. Herbert Franke noted that all occurrences of Po-lo or Bolod (an Altaic word meaning "steel") in Yuan texts were names of people of Mongol or Turkic extraction. The sinologist Paul Pelliot

thought that Polo might have served as an officer of the government

salt monopoly in Yangzhou, which was a position of some significance

that could explain the exaggeration. Polo also claimed to have provided the Mongols with technical advice on building mangonels during the Siege of Xiangyang, a claim that cannot possibly be true as the siege was over before Polo had arrived in China.

The Mongol army that besieged Xiangyang did have foreign military

engineers, but they were mentioned in Chinese sources as being from Baghdad and had Arabic names.

Stephen G. Haw,

however, challenges this idea that Polo exaggerated his own importance,

writing that, "contrary to what has often been said ... Marco does not

claim any very exalted position for himself in the Yuan empire." He points out that Polo never claimed to hold high rank, such as a darughachi, who led a tumen

– a unit that was normally 10,000 strong. In fact, Polo does not even

imply that he had led 1,000 personnel. Haw points out that Polo himself

appears to state only that he had been an emissary of the khan, in a

position with some esteem. According to Haw this is a reasonable claim

if Polo was, for example, a keshig – a member of the imperial guard by the same name, which included as many as 14,000 individuals at the time. Haw explains how the earliest manuscripts

of Polo's accounts provide contradicting information about his role in

Yangzhou, with some stating he was just a simple resident, others

stating he was a governor, and Ramusio's manuscript

claiming he was simply holding that office as a temporary substitute

for someone else, yet all the manuscripts concur that he worked as an

esteemed emissary for the khan.

Haw also objected to the approach to finding mention of Marco Polo in

Chinese texts, contending that contemporaneous Europeans had little

regard for using surnames, and a direct Chinese transcription of the name "Marco" ignores the possibility of him taking on a Chinese or even Mongol name that had no bearing or similarity with his Latin name.

Errors

A number of errors in Marco Polo's account have been noted: for example, he described the bridge later known as Marco Polo Bridge as having twenty-four arches instead of eleven or thirteen. He also said that city wall of Khanbaliq had twelve gates when it had only eleven. Archaeologists have also pointed out that Polo may have mixed up the details from the two attempted invasions of Japan by Kublai Khan

in 1274 and 1281. Polo wrote of five-masted ships, when archaeological

excavations found that the ships in fact had only three masts.

Appropriation

Wood accused Marco Polo of taking other people's accounts in his

book, retelling other stories as his own, or basing his accounts on

Persian guidebooks or other lost sources. For example, Sinologist Francis Woodman Cleaves noted that Polo's account of the voyage of the princess Kököchin from China to Persia to marry the Īl-khān in 1293 has been confirmed by a passage in the 15th-century Chinese work Yongle Encyclopedia and by the Persian historian Rashid-al-Din Hamadani in his work Jami' al-tawarikh. However neither of these accounts mentions Polo or indeed any European as part of the bridal party,

and Wood used the lack of mention of Polo in these works as an example

of Polo's "retelling of a well-known tale". Morgan, in Polo's defence,

noted that even the princess herself was not mentioned in the Chinese

source, and that it would have been surprising if Polo had been

mentioned by Rashid-al-Din. Historian Igor de Rachewiltz strongly criticised Wood's arguments in his review of her book.

Rachewiltz argued that Marco Polo's account in fact allows the Persian

and Chinese sources to be reconciled – by relaying the information that

two of the three envoys sent (mentioned in the Chinese source and whose

names accord with those given by Polo) had died during the voyage, it

explains why only the third who survived, Coja/Khoja, was mentioned by

Rashìd al-Dìn. Polo had therefore completed the story by providing

information not found in either source. He also noted that the only

Persian source that mentions the princess was not completed until

1310–11, therefore Marco Polo could not have learned the information

from any Persian book. According to de Rachewiltz, the concordance of

Polo's detailed account of the princess with other independent sources

that gave only incomplete information is proof of the veracity of Polo's

story and his presence in China.

Assessments

Morgan writes that since much of what The Book of Marvels has

to say about China is "demonstrably correct", any claim that Polo did

not go to China "creates far more problems than it solves", therefore

the "balance of probabilities" strongly suggests that Polo really did go

to China, even if he exaggerated somewhat his importance in China.

Haw dismisses the various anachronistic criticisms of Polo's accounts

that started in the 17th century, and highlights Polo's accuracy in

great part of his accounts, for example on the lay of the land such as

the Grand Canal of China. "If Marco was a liar," Haw writes, "then he must have been an implausibly meticulous one."

In 2012, the University of Tübingen Sinologist and historian Hans Ulrich Vogel released a detailed analysis of Polo's description of currencies, salt production

and revenues, and argued that the evidence supports his presence in

China because he included details which he could not have otherwise

known.

Vogel noted that no other Western, Arab, or Persian sources have given

such accurate and unique details about the currencies of China, for

example, the shape and size of the paper, the use of seals, the various

denominations of paper money as well as variations in currency usage in

different regions of China, such as the use of cowry shells in Yunnan, details supported by archaeological evidence and Chinese sources compiled long after Polo's had left China.

His accounts of salt production and revenues from the salt monopoly

are also accurate, and accord with Chinese documents of the Yuan era. Economic historian Mark Elvin,

in his preface to Vogel's 2013 monograph, concludes that Vogel

"demonstrates by specific example after specific example the ultimately

overwhelming probability of the broad authenticity" of Polo's account.

Many problems were caused by the oral transmission of the original text

and the proliferation of significantly different hand-copied

manuscripts. For instance, did Polo exert "political authority" (seignora) in Yangzhou or merely "sojourn" (sejourna)

there. Elvin concludes that "those who doubted, although mistaken, were

not always being casual or foolish", but "the case as a whole had now

been closed": the book is, "in essence, authentic, and, when used with

care, in broad terms to be trusted as a serious though obviously not

always final, witness."

Legacy

Further exploration

Handwritten notes by Christopher Columbus on a Latin edition of Polo's book.

The Fra Mauro map, published c. 1450 by the Venetian monk Fra Mauro.

Other lesser-known European explorers had already travelled to China, such as Giovanni da Pian del Carpine, but Polo's book meant that his journey was the first to be widely known. Christopher Columbus

was inspired enough by Polo's description of the Far East to want to

visit those lands for himself; a copy of the book was among his

belongings, with handwritten annotations. Bento de Góis,

inspired by Polo's writings of a Christian kingdom in the east,

travelled 4,000 miles (6,400 km) in three years across Central Asia. He

never found the kingdom but ended his travels at the Great Wall of China in 1605, proving that Cathay was what Matteo Ricci (1552–1610) called "China".

Cartography

Marco Polo's travels may have had some influence on the development of European cartography, ultimately leading to the European voyages of exploration a century later. The 1453 Fra Mauro map was said by Giovanni Battista Ramusio

(disputed by historian/cartographer Piero Falchetta, in whose work the

quote appears) to have been partially based on the one brought from Cathay by Marco Polo:

That fine illuminated world map on parchment, which can still be seen in a large cabinet alongside the choir of their monastery [the Camaldolese monastery of San Michele di Murano] was by one of the brothers of the monastery, who took great delight in the study of cosmography, diligently drawn and copied from a most beautiful and very old nautical map and a world map that had been brought from Cathay by the most honourable Messer Marco Polo and his father.

Though Marco Polo never produced a map that illustrated his journey,

his family drew several maps to the Far East based on the wayward's

accounts. These collection of maps were signed by Polo's three

daughters: Fantina, Bellela and Moreta. Not only did it contain maps of his journey, but also sea routes to Japan, Siberia's Kamchatka Peninsula, the Bering Strait and even to the coastlines of Alaska, centuries before the rediscovery of the Americas by Europeans.

Commemoration

Italian banknote, issued in 1982, portraying Marco Polo.

The Marco Polo sheep, a subspecies of Ovis ammon, is named after the explorer, who described it during his crossing of Pamir (ancient Mount Imeon) in 1271.

In 1851, a three-masted Clipper built in Saint John, New Brunswick also took his name; the Marco Polo was the first ship to sail around the world in under six months.

The airport in Venice is named Venice Marco Polo Airport.

The frequent flyer programme of Hong Kong flag carrier Cathay Pacific is known as the "Marco Polo Club".

Arts, entertainment, and media

Film

- The Adventures of Marco Polo (1938)

- Marco Polo (1961)

- Marco the Magnificent (1965)

Games

- The game "Marco Polo" is a form of tag played in a swimming pool or on land, with slightly modified rules.

- Polo appears as a Great Explorer in the strategy video game Civilization Revolution (2008).

- Marco Polo's 1292 voyage from China is used as a backdrop for the plot of Uncharted 2: Among Thieves (2009), where Nathan Drake (the protagonist) searches for the Cintamani Stone, which was from the fabled city of Shambhala.

- A board game 'The Voyages of Marco Polo' plays over a map of Eurasia, with multiple routes to 'recreate' Polo's journey.

Literature

The travels of Marco Polo are fictionalised in a number works, such as:

- Brian Oswald Donn-Byrne's Messer Marco Polo (1921)

- Italo Calvino's novel Invisible Cities (1972), in which Polo appears as a pivotal character.

- Gary Jennings' novel The Journeyer (1984)

- Avram Davidson's novel (written with Grania Davis) Marco Polo and the Sleeping Beauty (1988), a serio-comic fantasy with Polo as the protagonist.

- James Rollins' SIGMA Force Book 4: The Judas Strain (2007), in which facts about Polo's travels and conjecture about secrets he kept are interleaved with modern-day action.

Television

- Marco Polo was portrayed by Mark Eden in the serial of the same name of the television series Doctor Who.

- The television miniseries, Marco Polo (1982), featuring Ken Marshall, Burt Lancaster and Ruocheng Ying, and directed by Giuliano Montaldo, depicts Polo's travels. It won two Emmy Awards, and was nominated for six more.

- The television film, Marco Polo (2007), starring Brian Dennehy as Kublai Khan, and Ian Somerhalder as Marco, portrays Marco Polo being left alone in China while his uncle and father return to Venice, to be reunited with him many years later.

- In the Footsteps of Marco Polo (2009) is a PBS documentary about two friends (Denis Belliveau and Francis O'Donnell) who conceived of the ultimate road trip to retrace Marco Polo's journey from Venice to China via land and sea.

- Marco Polo (2014–2016) was a Netflix television drama series about Marco Polo's early years in the court of Kublai Khan created by John Fusco.