| Pancreatic islets/ islets of langerhans | |

|---|---|

| |

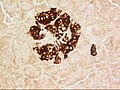

A pancreatic islet from a mouse in a typical position, close to a blood vessel; insulin in red, nuclei in blue. | |

| Details | |

| Part of | Pancreas |

| System | Endocrine |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | insulae pancreaticae |

| MeSH | D007515 |

| TA98 | A05.9.01.019 |

| TA2 | 3128 |

| FMA | 16016 |

| Anatomical terms of microanatomy | |

The pancreatic islets or islets of Langerhans are the regions of the pancreas that contain its endocrine (hormone-producing) cells, discovered in 1869 by German pathological anatomist Paul Langerhans. The pancreatic islets constitute 1–2% of the pancreas volume and receive 10–15% of its blood flow. The pancreatic islets are arranged in density routes throughout the human pancreas, and are important in the metabolism of glucose.

Structure

There are about 1 million islets distributed in the form of density routes throughout the pancreas of a healthy adult human, each of which measures an average of about 0.2 mm in diameter. Each is separated from the surrounding pancreatic tissue by a thin fibrous connective tissue capsule which is continuous with the fibrous connective tissue that is interwoven throughout the rest of the pancreas.

Microanatomy

Hormones produced in the pancreatic islets are secreted directly into the blood flow by (at least) five types of cells. In rat islets, endocrine cell subsets are distributed as follows:

- Alpha cells producing glucagon (20% of total islet cells)

- Beta cells producing insulin and amylin (≈70%)

- Delta cells producing somatostatin (<10%)

- Epsilon cells producing ghrelin (<1%)

- PP cells (gamma cells or F cells) producing pancreatic polypeptide (<5%)

It has been recognized that the cytoarchitecture of pancreatic islets differs between species. In particular, while rodent islets are characterized by a predominant proportion of insulin-producing beta cells in the core of the cluster and by scarce alpha, delta and PP cells in the periphery, human islets display alpha and beta cells in close relationship with each other throughout the cluster.

The proportion of beta cells in islets varies depending on the species, in humans it is about 40-50%. In addition to endocrine cells, there are stromal cells (fibroblasts), vascular cells (endothelial cells, pericytes), immune cells (granulocytes, lymphocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells) or neural cells.

A large amount of blood flows through the islets, 5–6 ml/min per 1 g of islet. It is up to 15 times more than in exocrine tissue of pancreas.

Islets can influence each other through paracrine and autocrine communication, and beta cells are coupled electrically to six to seven other beta cells (but not to other cell types).

Function

The paracrine feedback system of the pancreatic islets has the following structure:

- Glucose/Insulin: activates beta cells and inhibits alpha cells

- Glycogen/Glucagon: activates alpha cells which activates beta cells and delta cells

- Somatostatin: inhibits alpha cells and beta cells

A large number of G protein-coupled receptors (GPCRs) regulate the secretion of insulin, glucagon and somatostatin from pancreatic islets, and some of these GPCRs are the targets of drugs used to treat type-2 diabetes (ref GLP-1 receptor agonists, DPPIV inhibitors).

Electrical activity

Electrical activity of pancreatic islets has been studied using patch clamp techniques. It has turned out that the behavior of cells in intact islets differs significantly from the behavior of dispersed cells.

Clinical significance

Diabetes

The beta cells of the pancreatic islets secrete insulin, and so play a significant role in diabetes. It is thought that they are destroyed by immune assaults. However, there are also indications that beta cells have not been destroyed but have only become non-functional.

Transplantation

Because the beta cells in the pancreatic islets are selectively destroyed by an autoimmune process in type 1 diabetes, clinicians and researchers are actively pursuing islet transplantation as a means of restoring physiological beta cell function, which would offer an alternative to a complete pancreas transplant or artificial pancreas. Islet transplantation emerged as a viable option for the treatment of insulin requiring diabetes in the early 1970s with steady progress over the last three decades. Recent clinical trials have shown that insulin independence and improved metabolic control can be reproducibly obtained after transplantation of cadaveric donor islets into patients with unstable type 1 diabetes.

People with a high BMI are unsuitable pancreatic donors due to greater technical complications during transplantation. However, it is possible to isolate a larger number of islets because of their larger pancreas, and therefore they are more suitable donors of islets.

Islet transplantation only involves the transfer of tissue consisting of beta cells that are necessary as a treatment of this disease. It thus represents an advantage over whole pancreas transplantation, which is more technically demanding and poses a risk of, for example, pancreatitis leading to organ loss. Another advantage is that patients do not require general anesthesia.

Islet transplantation for type 1 diabetes currently requires potent immunosuppression to prevent host rejection of donor islets.

The islets are transplanted into a portal vein, which is then implanted in the liver. There is a risk of portal venous branch thrombosis and the low value of islet survival a few minutes after transplantation, because the vascular density at this site is after the surgery several months lower than in endogenous islets. Thus, neovascularization is key to islet survival, that is supported, for example, by VEGF produced by islets and vascular endothelial cells. However, intraportal transplantation has some other shortcomings, and so other alternative sites that would provide better microenvironment for islets implantation are being examined. Islet transplant research also focuses on islet encapsulation, CNI-free (calcineurin-inhibitor) immunosuppression, biomarkers of islet damage or islet donor shortage.

An alternative source of beta cells, such insulin-producing cells derived from adult stem cells or progenitor cells would contribute to overcoming the shortage of donor organs for transplantation. The field of regenerative medicine is rapidly evolving and offers great hope for the nearest future. However, type 1 diabetes is the result of the autoimmune destruction of beta cells in the pancreas. Therefore, an effective cure will require a sequential, integrated approach that combines adequate and safe immune interventions with beta cell regenerative approaches. It has also been demonstrated that alpha cells can spontaneously switch fate and transdifferentiate into beta cells in both healthy and diabetic human and mouse pancreatic islets, a possible future source for beta cell regeneration. In fact, it has been found that islet morphology and endocrine differentiation are directly related. Endocrine progenitor cells differentiate by migrating in cohesion and forming bud-like islet precursors, or "peninsulas", in which alpha cells constitute the peninsular outer layer and beta cells form later beneath them.