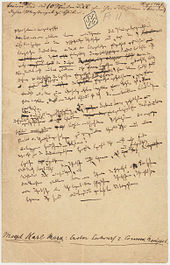

First edition in German | |

| Author | Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels |

|---|---|

| Translator | Samuel Moore |

| Country | United Kingdom |

| Language | German |

| Genre | philosophy |

Publication date | 21 February 1848 |

| Text | The Communist Manifesto at Wikisource |

The Communist Manifesto, originally the Manifesto of the Communist Party (German: Manifest der Kommunistischen Partei), is an 1848 pamphlet by German philosophers Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. Commissioned by the Communist League and originally published in London just as the Revolutions of 1848 began to erupt, the Manifesto was later recognised as one of the world's most influential political documents. It presents an analytical approach to the class struggle (historical and then-present) and the conflicts of capitalism and the capitalist mode of production, rather than a prediction of communism's potential future forms.

The Communist Manifesto summarises Marx and Engels' theories concerning the nature of society and politics, namely that in their own words "[t]he history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles". It also briefly features their ideas for how the capitalist society of the time would eventually be replaced by socialism. In the last paragraph of the Manifesto, the authors call for a "forcible overthrow of all existing social conditions", which served as a call for communist revolutions around the world.

In 2013, The Communist Manifesto was registered to UNESCO's Memory of the World Programme along with Marx's Capital, Volume I.

Synopsis

The Communist Manifesto is divided into a preamble and four sections, the last of these a short conclusion. The introduction begins: "A spectre is haunting Europe—the spectre of communism. All the powers of old Europe have entered into a holy alliance to exorcise this spectre." Pointing out that parties everywhere—including those in government and those in the opposition—have flung the "branding reproach of communism" at each other, the authors infer from this that the powers-that-be acknowledge communism to be a power in itself. Subsequently, the introduction exhorts Communists to openly publish their views and aims, to "meet this nursery tale of the spectre of communism with a manifesto of the party itself".

The first section of the Manifesto, "Bourgeois and Proletarians", elucidates the materialist conception of history, that "the history of all hitherto existing society is the history of class struggles". Societies have always taken the form of an oppressed majority exploited under the yoke of an oppressive minority. In capitalism, the industrial working class, or proletariat, engage in class struggle against the owners of the means of production, the bourgeoisie. As before, this struggle will end in a revolution that restructures society, or the "common ruin of the contending classes". The bourgeoisie, through the "constant revolutionising of production [and] uninterrupted disturbance of all social conditions" have emerged as the supreme class in society, displacing all the old powers of feudalism. The bourgeoisie constantly exploits the proletariat for its labour power, creating profit for themselves and accumulating capital. However, in doing so the bourgeoisie serves as "its own grave-diggers"; the proletariat inevitably will become conscious of their own potential and rise to power through revolution, overthrowing the bourgeoisie.

"Proletarians and Communists", the second section, starts by stating the relationship of conscious communists to the rest of the working class. The communists' party will not oppose other working-class parties, but unlike them, it will express the general will and defend the common interests of the world's proletariat as a whole, independent of all nationalities. The section goes on to defend communism from various objections, including claims that it advocates communal prostitution or disincentivises people from working. The section ends by outlining a set of short-term demands—among them a progressive income tax; abolition of inheritances and private property; abolition of child labour; free public education; nationalisation of the means of transport and communication; centralisation of credit via a national bank; expansion of publicly owned land, etc.—the implementation of which would result in the precursor to a stateless and classless society.

The third section, "Socialist and Communist Literature", distinguishes communism from other socialist doctrines prevalent at the time—these being broadly categorised as Reactionary Socialism; Conservative or Bourgeois Socialism; and Critical-Utopian Socialism and Communism. While the degree of reproach toward rival perspectives varies, all are dismissed for advocating reformism and failing to recognise the pre-eminent revolutionary role of the working class.

"Position of the Communists in Relation to the Various Opposition Parties", the concluding section of the Manifesto, briefly discusses the communist position on struggles in specific countries in the mid-nineteenth century such as France, Switzerland, Poland and Germany, this last being "on the eve of a bourgeois revolution" and predicts that a world revolution will soon follow. It ends by declaring an alliance with the democratic socialists, boldly supporting other communist revolutions and calling for united international proletarian action—"Working Men of All Countries, Unite!".

Writing

In spring 1847, Marx and Engels joined the League of the Just, who were quickly convinced by the duo's ideas of "critical communism". At its First Congress in 2–9 June, the League tasked Engels with drafting a "profession of faith", but such a document was later deemed inappropriate for an open, non-confrontational organisation. Engels nevertheless wrote the "Draft of a Communist Confession of Faith", detailing the League's programme. A few months later, in October, Engels arrived at the League's Paris branch to find that Moses Hess had written an inadequate manifesto for the group, now called the League of Communists. In Hess's absence, Engels severely criticised this manifesto, and convinced the rest of the League to entrust him with drafting a new one. This became the draft Principles of Communism, described as "less of a credo and more of an exam paper".

On 23 November, just before the Communist League's Second Congress (29 November – 8 December 1847), Engels wrote to Marx, expressing his desire to eschew the catechism format in favour of the manifesto, because he felt it "must contain some history." On the 28th, Marx and Engels met at Ostend in Belgium, and a few days later, gathered at the Soho, London headquarters of the German Workers' Education Association to attend the Congress. Over the next ten days, intense debate raged between League functionaries; Marx eventually dominated the others and, overcoming "stiff and prolonged opposition", in Harold Laski's words, secured a majority for his programme. The League thus unanimously adopted a far more combative resolution than that at the First Congress in June. Marx (especially) and Engels were subsequently commissioned to draw up a manifesto for the League.

Upon returning to Brussels, Marx engaged in "ceaseless procrastination", according to his biographer Francis Wheen. Working only intermittently on the Manifesto, he spent much of his time delivering lectures on political economy at the German Workers' Education Association, writing articles for the Deutsche-Brüsseler-Zeitung, and giving a long speech on free trade. Following this, he even spent a week (17–26 January 1848) in Ghent to establish a branch of the Democratic Association there. Subsequently, having not heard from Marx for nearly two months, the Central Committee of the Communist League sent him an ultimatum on 24 or 26 January, demanding he submit the completed manuscript by 1 February. This imposition spurred Marx on, who struggled to work without a deadline, and he seems to have rushed to finish the job in time. For evidence of this, historian Eric Hobsbawm points to the absence of rough drafts, only one page of which survives.

In all, the Manifesto was written over 6–7 weeks. Although Engels is credited as co-writer, the final draft was penned exclusively by Marx. From the 26 January letter, Laski infers that even the Communist League considered Marx to be the sole draftsman and that he was merely their agent, imminently replaceable. Further, Engels himself wrote in 1883: "The basic thought running through the Manifesto [...] belongs solely and exclusively to Marx". Although Laski does not disagree, he suggests that Engels underplays his own contribution with characteristic modesty and points out the "close resemblance between its substance and that of the [Principles of Communism]". Laski argues that while writing the Manifesto, Marx drew from the "joint stock of ideas" he developed with Engels "a kind of intellectual bank account upon which either could draw freely".

Publication

Initial publication and obscurity, 1848–1872

In late February 1848, the Manifesto was anonymously published by the Workers' Educational Association (Kommunistischer Arbeiterbildungsverein) at Bishopsgate in the City of London. Written in German, the 23-page pamphlet was titled Manifest der kommunistischen Partei and had a dark-green cover. It was reprinted three times and serialised in the Deutsche Londoner Zeitung, a newspaper for German émigrés. On 4 March, one day after the serialisation in the Zeitung began, Marx was expelled by Belgian police. Two weeks later, around 20 March, a thousand copies of the Manifesto reached Paris, and from there to Germany in early April. In April–May the text was corrected for printing and punctuation mistakes; Marx and Engels would use this 30-page version as the basis for future editions of the Manifesto.

Although the Manifesto's prelude announced that it was "to be published in the English, French, German, Italian, Flemish and Danish languages", the initial printings were only in German. Polish and Danish translations soon followed the German original in London, and by the end of 1848, a Swedish translation was published with a new title—The Voice of Communism: Declaration of the Communist Party. In June–November 1850 the Manifesto of the Communist Party was published in English for the first time when George Julian Harney serialised Helen Macfarlane's translation in his Chartist magazine The Red Republican. Her version begins: "A frightful hobgoblin stalks throughout Europe. We are haunted by a ghost, the ghost of Communism". For her translation, the Lancashire-based Macfarlane probably consulted Engels, who had abandoned his own English translation half way. Harney's introduction revealed the Manifesto's hitherto-anonymous authors' identities for the first time.

Soon after the Manifesto was published, Paris erupted in revolution to overthrow King Louis Philippe. The Manifesto played no role in this; a French translation was not published in Paris until just before the working-class June Days Uprising was crushed. Its influence in the Europe-wide Revolutions of 1848 was restricted to Germany, where the Cologne-based Communist League and its newspaper Neue Rheinische Zeitung, edited by Marx, played an important role. Within a year of its establishment, in May 1849, the Zeitung was suppressed; Marx was expelled from Germany and had to seek lifelong refuge in London. In 1851, members of the Communist League's central board were arrested by the Prussian police. At their trial in Cologne 18 months later in late 1852 they were sentenced to 3–6 years' imprisonment. For Engels, the revolution was "forced into the background by the reaction that began with the defeat of the Paris workers in June 1848, and was finally excommunicated 'by law' in the conviction of the Cologne Communists in November 1852".

After the defeat of the 1848 revolutions the Manifesto fell into obscurity, where it remained throughout the 1850s and 1860s. Hobsbawm says that by November 1850 the Manifesto "had become sufficiently scarce for Marx to think it worth reprinting section III [...] in the last issue of his [short-lived] London magazine". Over the next two decades only a few new editions were published; these include an (unauthorised and occasionally inaccurate) 1869 Russian translation by Mikhail Bakunin in Geneva and an 1866 edition in Berlin—the first time the Manifesto was published in Germany. According to Hobsbawm: "By the middle 1860s virtually nothing that Marx had written in the past was any longer in print". However, John Cowell-Stepney did publish an abridged version in the Social Economist in August/September 1869, in time for the Basle Congress.

Rise, 1872–1917

In the early 1870s, the Manifesto and its authors experienced a revival in fortunes. Hobsbawm identifies three reasons for this. The first is the leadership role Marx played in the International Workingmen's Association (aka the First International). Secondly, Marx also came into much prominence among socialists—and equal notoriety among the authorities—for his support of the Paris Commune of 1871, elucidated in The Civil War in France. Lastly, and perhaps most significantly in the popularisation of the Manifesto, was the treason trial of German Social Democratic Party (SPD) leaders. During the trial prosecutors read the Manifesto out loud as evidence; this meant that the pamphlet could legally be published in Germany. Thus in 1872 Marx and Engels rushed out a new German-language edition, writing a preface that identified that several portions that became outdated in the quarter century since its original publication. This edition was also the first time the title was shortened to The Communist Manifesto (Das Kommunistische Manifest), and it became the bedrock the authors based future editions upon. Between 1871 and 1873, the Manifesto was published in over nine editions in six languages; on December 30, 1871 it was published in the United States for the first time in Woodhull & Claflin's Weekly of New York City. However, by the mid 1870s the Communist Manifesto remained Marx and Engels' only work to be even moderately well-known.

Over the next forty years, as social-democratic parties rose across Europe and parts of the world, so did the publication of the Manifesto alongside them, in hundreds of editions in thirty languages. Marx and Engels wrote a new preface for the 1882 Russian edition, translated by Georgi Plekhanov in Geneva. In it they wondered if Russia could directly become a communist society, or if she would become capitalist first like other European countries. After Marx's death in 1883, Engels alone provided the prefaces for five editions between 1888 and 1893. Among these is the 1888 English edition, translated by Samuel Moore and approved by Engels, who also provided notes throughout the text. It has been the standard English-language edition ever since.

The principal region of its influence, in terms of editions published, was in the "central belt of Europe", from Russia in the east to France in the west. In comparison, the pamphlet had little impact on politics in southwest and southeast Europe, and moderate presence in the north. Outside Europe, Chinese and Japanese translations were published, as were Spanish editions in Latin America. This uneven geographical spread in the Manifesto's popularity reflected the development of socialist movements in a particular region as well as the popularity of Marxist variety of socialism there. There was not always a strong correlation between a social-democratic party's strength and the Manifesto's popularity in that country. For instance, the German SPD printed only a few thousand copies of the Communist Manifesto every year, but a few hundred thousand copies of the Erfurt Programme. Further, the mass-based social-democratic parties of the Second International did not require their rank and file to be well-versed in theory; Marxist works such as the Manifesto or Das Kapital were read primarily by party theoreticians. On the other hand, small, dedicated militant parties and Marxist sects in the West took pride in knowing the theory; Hobsbawm says: "This was the milieu in which 'the clearness of a comrade could be gauged invariably from the number of earmarks on his Manifesto'".

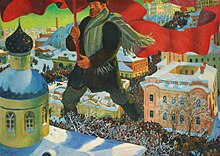

Ubiquity, 1917–present

Following the October Revolution of 1917 that swept the Vladimir Lenin-led Bolsheviks to power in Russia, the world's first socialist state was founded explicitly along Marxist lines. The Soviet Union, which Bolshevik Russia would become a part of, was a one-party state under the rule of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union (CPSU). Unlike their mass-based counterparts of the Second International, the CPSU and other Leninist parties like it in the Third International expected their members to know the classic works of Marx, Engels and Lenin. Further, party leaders were expected to base their policy decisions on Marxist-Leninist ideology. Therefore works such as the Manifesto were required reading for the party rank-and-file.

Therefore the widespread dissemination of Marx and Engels' works became an important policy objective; backed by a sovereign state, the CPSU had relatively inexhaustible resources for this purpose. Works by Marx, Engels, and Lenin were published on a very large scale, and cheap editions of their works were available in several languages across the world. These publications were either shorter writings or they were compendia such as the various editions of Marx and Engels' Selected Works, or their Collected Works. This affected the destiny of the Manifesto in several ways. Firstly, in terms of circulation; in 1932 the American and British Communist Parties printed several hundred thousand copies of a cheap edition for "probably the largest mass edition ever issued in English". Secondly the work entered political-science syllabuses in universities, which would only expand after the Second World War. For its centenary in 1948, its publication was no longer the exclusive domain of Marxists and academicians; general publishers too printed the Manifesto in large numbers. "In short, it was no longer only a classic Marxist document", Hobsbawm noted, "it had become a political classic tout court".

Even after the collapse of the Soviet Bloc in the 1990s, the Communist Manifesto remains ubiquitous; Hobsbawm says that "In states without censorship, almost certainly anyone within reach of a good bookshop, and certainly anyone within reach of a good library, not to mention the internet, can have access to it". The 150th anniversary once again brought a deluge of attention in the press and the academia, as well as new editions of the book fronted by introductions to the text by academics. One of these, The Communist Manifesto: A Modern Edition by Verso, was touted by a critic in the London Review of Books as being a "stylish red-ribboned edition of the work. It is designed as a sweet keepsake, an exquisite collector's item. In Manhattan, a prominent Fifth Avenue store put copies of this choice new edition in the hands of shop-window mannequins, displayed in come-hither poses and fashionable décolletage".

Legacy

"With the clarity and brilliance of genius, this work outlines a new world-conception, consistent materialism, which also embraces the realm of social life; dialectics, as the most comprehensive and profound doctrine of development; the theory of the class struggle and of the world-historic revolutionary role of the proletariat—the creator of a new, communist society."

—Vladimir Lenin on the Manifesto, 1914

A number of late-20th- and 21st-century writers have commented on the Communist Manifesto's continuing relevance. In a special issue of the Socialist Register commemorating the Manifesto's 150th anniversary, Peter Osborne argued that it was "the single most influential text written in the nineteenth century". Academic John Raines in 2002 noted: "In our day this Capitalist Revolution has reached the farthest corners of the earth. The tool of money has produced the miracle of the new global market and the ubiquitous shopping mall. Read The Communist Manifesto, written more than one hundred and fifty years ago, and you will discover that Marx foresaw it all". In 2003, English Marxist Chris Harman stated: "There is still a compulsive quality to its prose as it provides insight after insight into the society in which we live, where it comes from and where it's going to. It is still able to explain, as mainstream economists and sociologists cannot, today's world of recurrent wars and repeated economic crisis, of hunger for hundreds of millions on the one hand and 'overproduction' on the other. There are passages that could have come from the most recent writings on globalisation". Alex Callinicos, editor of International Socialism, stated in 2010: "This is indeed a manifesto for the 21st century". Writing in The London Evening Standard , Andrew Neather cited Verso Books' 2012 re-edition of The Communist Manifesto with an introduction by Eric Hobsbawm as part of a resurgence of left-wing-themed ideas which includes the publication of Owen Jones' best-selling Chavs: The Demonization of the Working Class and Jason Barker's documentary Marx Reloaded.

In contrast, critics such as revisionist Marxist and reformist socialist Eduard Bernstein distinguished between "immature" early Marxism—as exemplified by The Communist Manifesto written by Marx and Engels in their youth—that he opposed for its violent Blanquist tendencies and later "mature" Marxism that he supported. This latter form refers to Marx in his later life acknowledging that socialism could be achieved through peaceful means through legislative reform in democratic societies. Bernstein declared that the massive and homogeneous working-class claimed in the Communist Manifesto did not exist, and that contrary to claims of a proletarian majority emerging, the middle-class was growing under capitalism and not disappearing as Marx had claimed. Bernstein noted that the working-class was not homogeneous but heterogeneous, with divisions and factions within it, including socialist and non-socialist trade unions. Marx himself, later in his life, acknowledged that the middle-class was not disappearing in his work Theories of Surplus Value (1863). The obscurity of the later work means that Marx's acknowledgement of this error is not well known. George Boyer described the Manifesto as "very much a period piece, a document of what was called the 'hungry' 1840s".

Many have drawn attention to the passage in the Manifesto that seems to sneer at the stupidity of the rustic: "The bourgeoisie [...] draws all nations [...] into civilisation[.] [...] It has created enormous cities [...] and thus rescued a considerable part of the population from the idiocy [sic] of rural life". However, as Eric Hobsbawm noted:

[W]hile there is no doubt that Marx at this time shared the usual townsman's contempt for, as well as ignorance of, the peasant milieu, the actual and analytically more interesting German phrase ("dem Idiotismus des Landlebens entrissen") referred not to "stupidity" but to "the narrow horizons", or "the isolation from the wider society" in which people in the countryside lived. It echoed the original meaning of the Greek term idiotes from which the current meaning of "idiot" or "idiocy" is derived, namely "a person concerned only with his own private affairs and not with those of the wider community". In the course of the decades since the 1840s, and in movements whose members, unlike Marx, were not classically educated, the original sense was lost and was misread.

Influences

Marx and Engels' political influences were wide-ranging, reacting to and taking inspiration from German idealist philosophy, French socialism, and English and Scottish political economy. The Communist Manifesto also takes influence from literature. In Jacques Derrida’s work, Specters of Marx: The State of the Debt, the Work of Mourning and the New International, he uses William Shakespeare’s Hamlet to frame a discussion of the history of the International, showing in the process the influence that Shakespeare's work had on Marx and Engels’ writing. In his essay, "Big Leagues: Specters of Milton and Republican International Justice between Shakespeare and Marx", Christopher N. Warren makes the case that English poet John Milton also had a substantial influence on Marx and Engels' work. Historians of 19th-century reading habits have confirmed that Marx and Engels would have read these authors and it is known that Marx loved Shakespeare in particular. Milton, Warren argues, also shows a notable influence on The Communist Manifesto, saying: "Looking back on Milton’s era, Marx saw a historical dialectic founded on inspiration in which freedom of the press, republicanism, and revolution were closely joined". Milton’s republicanism, Warren continues, served as "a useful, if unlikely, bridge" as Marx and Engels sought to forge a revolutionary international coalition.