Zionism (Hebrew: צִיּוֹנוּת Tsiyyonut [tsijoˈnut] after Zion) is an ideology and nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a Jewish state centered in the area roughly corresponding to Canaan, the Holy Land, the region of Palestine or Eretz Israel on the basis of a long Jewish connection and attachment to that land.

Modern Zionism emerged in the late 19th century in Central and Eastern Europe as a national revival movement, both in reaction to newer waves of antisemitism and as a response to Haskalah, or Jewish Enlightenment. Soon after this, most leaders of the movement associated the main goal with creating the desired state in Palestine, then an area controlled by the Ottoman Empire.

Zionism posited a negation of Jewish life in the diaspora and, until 1948 perceived its primary goal as an ideal ingathering of exiles (kibbutz galuyot) in the ancient heartland of the Jewish people, and, through the establishment of a state, the liberation of Jews from the persecutions, humiliations, discrimination and antisemitism they had been subject to. Since the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948, Zionism has continued primarily to advocate on behalf of Israel and to address threats to its continued existence and security.

A religious variety of Zionism supports Jews upholding their Jewish identity defined as adherence to religious Judaism, opposes the assimilation of Jews into other societies, and has advocated the return of Jews to Israel as a means for Jews to be a majority nation in their own state. A variety of Zionism, called cultural Zionism, founded and represented most prominently by Ahad Ha'am, fostered a secular vision of a Jewish "spiritual center" in Israel. Unlike Herzl, the founder of political Zionism, Ahad Ha'am strived for Israel to be "a Jewish state and not merely a state of Jews".

Advocates of Zionism view it as a national liberation movement for the repatriation of a persecuted people residing as minorities in a variety of nations to their ancestral homeland. Critics of Zionism view it as a colonialist, racist, and exceptionalist ideology that led advocates to violence during Mandatory Palestine, followed by the exodus of Palestinians, and the subsequent denial of their right to return to lands and property lost during the 1948 and 1967 wars.

Terminology

The term "Zionism" is derived from the word Zion (Hebrew: ציון ,Tzi-yon), referring to Jerusalem. Throughout eastern Europe in the late 19th century, numerous grassroots groups promoted the national resettlement of the Jews in their homeland, as well as the revitalization and cultivation of the Hebrew language. These groups were collectively called the "Lovers of Zion" and were seen as countering a growing Jewish movement toward assimilation. The first use of the term is attributed to the Austrian Nathan Birnbaum, founder of the Kadimah nationalist Jewish students' movement; he used the term in 1890 in his journal Selbstemanzipation! (Self-Emancipation), itself named almost identically to Leon Pinsker's 1882 book Auto-Emancipation.

Overview

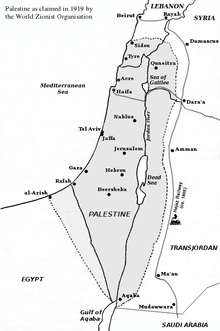

The common denominator among all Zionists has been a claim to the land historically known as Palestine, and in Jewish writings as Eretz Israel as a national homeland of the Jews and as the legitimate focus for Jewish national self-determination. It is based on historical ties and religious traditions linking the Jewish people to the Land of Israel. Zionism does not have a uniform ideology, but has evolved in a dialogue among a plethora of ideologies: General Zionism, Religious Zionism, Labor Zionism, Revisionist Zionism, Green Zionism, etc. In the early decades it foresaw the homeland of the Jews as extending not only over historic Palestine, but into Lebanon, Syria, Jordan, and Egypt, with its borders more or less coinciding with the major riverine and water-rich areas of the Levant.

After almost two millennia of the Jewish diaspora residing in various countries without a national state, the Zionist movement was founded in the late 19th century by secular Jews, largely as a response by Ashkenazi Jews to rising antisemitism in Europe, exemplified by the Dreyfus affair in France and the anti-Jewish pogroms in the Russian Empire. The political movement was formally established by the Austro-Hungarian journalist Theodor Herzl in 1897 following the publication of his book Der Judenstaat (The Jewish State). At that time, the movement sought to encourage Jewish migration to Ottoman Palestine particularly among those Jewish communities who were poor, unassimilated and whose 'floating' presence caused disquiet, in Herzl's view, among assimilated Jews and stirred anti-Semitism among Christians.

"I believe that a wondrous generation of Jews will spring into existence. The Maccabeans will rise again. Let me repeat once more my opening words: The Jews who wish for a State will have it. We shall live at last as free men on our own soil, and die peacefully in our own homes. The world will be freed by our liberty, enriched by our wealth, magnified by our greatness. And whatever we attempt there to accomplish for our own welfare, will react powerfully and beneficially for the good of humanity."

Theodore Herzl, concluding words of The Jewish State, 1896

Although initially one of several Jewish political movements offering alternative responses to Jewish assimilation and antisemitism, Zionism expanded rapidly. In its early stages, supporters considered setting up a Jewish state in the historic territory of Palestine. After World War II and the destruction of Jewish life in Central and Eastern Europe where these alternative movements were rooted, it became dominant in the thinking about a Jewish national state.

Creating an alliance with Great Britain and securing support for some years for Jewish emigration to Palestine, Zionists also recruited European Jews to immigrate there, especially Jews who lived in areas of the Russian Empire where anti-semitism was raging. The alliance with Britain was strained as the latter realized the implications of the Jewish movement for Arabs in Palestine, but the Zionists persisted. The movement was eventually successful in establishing Israel on May 14, 1948 (5 Iyyar 5708 in the Hebrew calendar), as the homeland for the Jewish people. The proportion of the world's Jews living in Israel has steadily grown since the movement emerged. By the early 21st century, more than 40% of the world's Jews lived in Israel, more than in any other country. These two outcomes represent the historical success of Zionism and are unmatched by any other Jewish political movement in the past 2,000 years. In some academic studies, Zionism has been analyzed both within the larger context of diaspora politics and as an example of modern national liberation movements.

Zionism also sought the assimilation of Jews into the modern world. As a result of the diaspora, many of the Jewish people remained outsiders within their adopted countries and became detached from modern ideas. So-called "assimilationist" Jews desired complete integration into European society. They were willing to downplay their Jewish identity and in some cases to abandon traditional views and opinions in an attempt at modernization and assimilation into the modern world. A less extreme form of assimilation was called cultural synthesis. Those in favor of cultural synthesis desired continuity and only moderate evolution, and were concerned that Jews should not lose their identity as a people. "Cultural synthesists" emphasized both a need to maintain traditional Jewish values and faith and a need to conform to a modernist society, for instance, in complying with work days and rules.

In 1975, the United Nations General Assembly passed Resolution 3379, which designated Zionism as "a form of racism and racial discrimination". The resolution was repealed in 1991 by replacing Resolution 3379 with Resolution 46/86. Opposition to Zionism (being against a Jewish state), according to historian Geoffrey Alderman, can be legitimately described as racist.

Beliefs

Zionism was established with the political goal of creating a Jewish state in order to create a nation where Jews could be the majority, rather than the minority which they were in a variety of nations in the diaspora. Theodor Herzl, the ideological father of Zionism, considered Antisemitism to be an eternal feature of all societies in which Jews lived as minorities, and that only a separation could allow Jews to escape eternal persecution. "Let them give us sovereignty over a piece of the Earth's surface, just sufficient for the needs of our people, then we will do the rest!" he proclaimed exposing his plan.

Herzl considered two possible destinations to colonize, Argentina and Palestine. Jewish settlement of Argentina was the project of Maurice de Hirsch. Herzl preferred Argentina for its vast and sparsely populated territory and temperate climate but conceded that Palestine would have greater attraction because of the historic ties of Jews with that area. He also accepted to evaluate Joseph Chamberlain's proposal for possible Jewish settlement in Great Britain's East African colonies.

Aliyah (migration, literally "ascent") to the Land of Israel is a recurring theme in Jewish prayers. Rejection of life in the Diaspora is a central assumption in Zionism. Supporters of Zionism believed that Jews in the Diaspora were prevented from their full growth in Jewish individual and national life.

Zionists generally preferred to speak Hebrew, a Semitic language that developed under conditions of freedom in ancient Judah, and worked to modernize and adapt it for everyday use. Zionists sometimes refused to speak Yiddish, a language they thought had developed in the context of European persecution. Once they moved to Israel, many Zionists refused to speak their (diasporic) mother tongues and adopted new, Hebrew names. Hebrew was preferred not only for ideological reasons, but also because it allowed all citizens of the new state to have a common language, thus furthering the political and cultural bonds among Zionists.

Major aspects of the Zionist idea are represented in the Israeli Declaration of Independence:

The Land of Israel was the birthplace of the Jewish people. Here their spiritual, religious and political identity was shaped. Here they first attained to statehood, created cultural values of national and universal significance and gave to the world the eternal Book of Books.

After being forcibly exiled from their land, the people kept faith with it throughout their Dispersion and never ceased to pray and hope for their return to it and for the restoration in it of their political freedom.

Impelled by this historic and traditional attachment, Jews strove in every successive generation to re-establish themselves in their ancient homeland. In recent decades they returned in their masses.

History

| Year | Muslims | Jews | Christians | Others | Total Settled |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1922 | 486,177 (74.9%) | 83,790 (12.9%) | 71,464 (11.0%) | 7,617 (1.2%) | 649,048 |

| 1931 | 693,147 (71.7%) | 174,606 (18.1%) | 88,907 (9.2%) | 10,101 (1.0%) | 966,761 |

| 1941 | 906,551 (59.7%) | 474,102 (31.2%) | 125,413 (8.3%) | 12,881 (0.8%) | 1,518,947 |

| 1946 | 1,076,783 (58.3%) | 608,225 (33.0%) | 145,063 (7.9%) | 15,488 (0.8%) | 1,845,559 |

Since the first centuries of the CE, most Jews have lived outside the area commonly known as Palestine, following the destruction of the Second Temple and the massacre of the Jews in Jerusalem. Of the 600,000 (Tacitus) or 1,000,000 (Josephus) Jews of Jerusalem, all of them either died of starvation, were killed or were sold into slavery. A minority presence of Jews has been attested for almost all of the period. For example, according to tradition, the Jewish community of Peki'in has maintained a Jewish presence since the Second Temple period. According to the Tanakh, God had assigned Canaan to the Jews as a Promised Land, a belief conserved also in the Septuagint and both Christian and Islamic tradition. The Diaspora began in 586 BCE during the Babylonian occupation of Israel. The Babylonians destroyed the First Temple, which was central to Jewish culture at the time. After the 1st-century Great Revolt and the 2nd-century Bar Kokhba revolt, the Roman Empire banned Jews from Jerusalem and called the territory Syria Palaestina.

Zion is a hill near Jerusalem (now in the city), widely symbolizing the Land of Israel.

In the middle of the 16th century, the Portuguese Sephardi Joseph Nasi, with the support of the Ottoman Empire, tried to gather the Portuguese Jews, first to migrate to Cyprus, then owned by the Republic of Venice, and later to resettle in Tiberias. Nasi – who never converted to Islam – eventually obtained the highest medical position in the empire, and actively participated in court life. He convinced Suleiman I to intervene with the Pope on behalf of Ottoman-subject Portuguese Jews imprisoned in Ancona. Between the 4th and 19th centuries, Nasi's was the only practical attempt to establish some sort of Jewish political center in Palestine.

In the 17th century Sabbatai Zevi (1626–1676) announced himself as the Messiah and gained many Jews to his side, forming a base in Salonika. He first tried to establish a settlement in Gaza, but moved later to Smyrna. After deposing the old rabbi Aaron Lapapa in the spring of 1666, the Jewish community of Avignon, France prepared to emigrate to the new kingdom. The readiness of the Jews of the time to believe the messianic claims of Sabbatai Zevi may be largely explained by the desperate state of Central European Jewry in the mid-17th century. The bloody pogroms of Bohdan Khmelnytsky had wiped out one-third of the Jewish population and destroyed many centers of Jewish learning and communal life.

In the 19th century, a current in Judaism supporting a return to Zion grew in popularity, particularly in Europe, where antisemitism and hostility toward Jews were growing. The idea of returning to Palestine was rejected by the conferences of rabbis held in that epoch. Individual efforts supported the emigration of groups of Jews to Palestine, pre-Zionist Aliyah, even before 1897, the year considered as the start of practical Zionism.

The Reformed Jews rejected this idea of a return to Zion. The conference of rabbis, at Frankfurt am Main, July 15–28, 1845, deleted from the ritual all prayers for a return to Zion and a restoration of a Jewish state. The Philadelphia Conference, 1869, followed the lead of the German rabbis and decreed that the Messianic hope of Israel is "the union of all the children of God in the confession of the unity of God". The Pittsburgh Conference, 1885, reiterated this Messianic idea of reformed Judaism, expressing in a resolution that "we consider ourselves no longer a nation, but a religious community; and we therefore expect neither a return to Palestine, nor a sacrificial worship under the sons of Aaron, nor the restoration of any of the laws concerning a Jewish state".

Jewish settlements were proposed for establishment in the upper Mississippi region by W.D. Robinson in 1819. Others were developed near Jerusalem in 1850, by the American Consul Warder Cresson, a convert to Judaism. Cresson was tried and condemned for lunacy in a suit filed by his wife and son. They asserted that only a lunatic would convert to Judaism from Christianity. After a second trial, based on the centrality of American 'freedom of faith' issues and antisemitism, Cresson won the bitterly contested suit. He emigrated to Ottoman Palestine and established an agricultural colony in the Valley of Rephaim of Jerusalem. He hoped to "prevent any attempts being made to take advantage of the necessities of our poor brethren ... (that would) ... FORCE them into a pretended conversion."

Moral but not practical efforts were made in Prague to organize a Jewish emigration, by Abraham Benisch and Moritz Steinschneider in 1835. In the United States, Mordecai Noah attempted to establish a Jewish refuge opposite Buffalo, New York on Grand Isle, 1825. These early Jewish nation building efforts of Cresson, Benisch, Steinschneider and Noah failed.

Sir Moses Montefiore, famous for his intervention in favor of Jews around the world, including the attempt to rescue Edgardo Mortara, established a colony for Jews in Palestine. In 1854, his friend Judah Touro bequeathed money to fund Jewish residential settlement in Palestine. Montefiore was appointed executor of his will, and used the funds for a variety of projects, including building in 1860 the first Jewish residential settlement and almshouse outside of the old walled city of Jerusalem—today known as Mishkenot Sha'ananim. Laurence Oliphant failed in a like attempt to bring to Palestine the Jewish proletariat of Poland, Lithuania, Romania, and the Turkish Empire (1879 and 1882).

The official beginning of the construction of the New Yishuv in Palestine is usually dated to the arrival of the Bilu group in 1882, who commenced the First Aliyah. In the following years, Jewish immigration to Palestine started in earnest. Most immigrants came from the Russian Empire, escaping the frequent pogroms and state-led persecution in what are now Ukraine and Poland. They founded a number of agricultural settlements with financial support from Jewish philanthropists in Western Europe. Additional Aliyahs followed the Russian Revolution and its eruption of violent pogroms. At the end of the 19th century, Jews were a small minority in Palestine.

In the 1890s, Theodor Herzl infused Zionism with a new ideology and practical urgency, leading to the First Zionist Congress at Basel in 1897, which created the World Zionist Organization (WZO). Herzl's aim was to initiate necessary preparatory steps for the development of a Jewish state. Herzl's attempts to reach a political agreement with the Ottoman rulers of Palestine were unsuccessful and he sought the support of other governments. The WZO supported small-scale settlement in Palestine; it focused on strengthening Jewish feeling and consciousness and on building a worldwide federation.

The Russian Empire, with its long record of state-organized genocide and ethnic cleansing ("pogroms"), was widely regarded as the historic enemy of the Jewish people. The Zionist movement's headquarters were located in Berlin, as many of its leaders were German Jews who spoke German.

Organisation

Zionism developed from Proto-Zionist initiatives and movements, such as Hovevei Zion. It coalesced and became organised in the form of the Zionist Congress, which created nation-building institutions and acted in Ottoman and British Palestine as well as internationally.

Pre-state institutions

- Zionist Organization (ZO), est. 1897

- Zionist Congress (est. 1897), the supreme organ of the ZO

- Palestine Office (est. 1908), the executive arm of the ZO in Palestine

- Jewish National Fund (JNF), est. 1901 to buy and develop land in Palestine

- Keren Hayesod, est. 1920 to collect funds

- Jewish Agency, est. 1929 as the worldwide operative branch of the ZO

Funding

The Zionist enterprise was mainly funded by major benefactors who made large contributions, sympathisers from Jewish communities across the world (see for instance the Jewish National Fund's collection boxes), and the settlers themselves. The movement established a bank for administering its finances, the Jewish Colonial Trust (est. 1888, incorporated in London in 1899). A local subsidiary was formed in 1902 in Palestine, the Anglo-Palestine Bank.

A list of pre-state large contributors to Pre-Zionist and Zionist enterprises would include, alphabetically,

- Isaac Leib Goldberg (1860–1935), Zionist leader and philanthropist from Russia

- Maurice de Hirsch (1831–1896), German Jewish financier and philanthropist, founder of the Jewish Colonization Association

- Moses Montefiore (1784–1885), British Jewish banker and philanthropist in Britain and the Levant, initiator and financier of Proto-Zionism

- Edmond James de Rothschild (1845–1934), French Jewish banker and major donor of the Zionist project

Pre-state self-defense

A list of Jewish pre-state self-defense organisations in Palestine would include

- Bar-Giora (organization) (1907-1909)

- HaMagen, "The Shield" (1915–17)

- HaNoter, "The Guard" (pre-WWI, distinct from the British Madate-period Notrim)

- Hashomer (1909-1920)

- Haganah (1920-1948)

- Palmach (1941-1948)

Territories considered

Throughout the first decade of the Zionist movement, there were several instances where Zionist figures supported a Jewish state in places outside Palestine, such as Uganda and Argentina. Even Theodor Herzl, the founder of political Zionism was initially content with any Jewish self-governed state. A major concern in considering other territories was the Russian pogroms, in particular the Kishinev massacre, and the resultant need for quick resettlement. However, other Zionists emphasized the memory, emotion and tradition linking Jews to the Land of Israel. Zion became the name of the movement, after the place where King David established his kingdom, following his conquest of the Jebusite fortress there (II Samuel 5:7, I Kings 8:1). The name Zion was synonymous with Jerusalem. Palestine only became Herzl's main focus after his Zionist manifesto 'Der Judenstaat' was published in 1896, but even then he was hesitant to focus efforts solely on resettlement in Palestine when speed was of the essence.

In 1903, British Colonial Secretary Joseph Chamberlain offered Herzl 5,000 square miles in the Uganda Protectorate for Jewish settlement. Called the Uganda Scheme, it was introduced the same year to the World Zionist Organization's Congress at its sixth meeting, where a fierce debate ensued. Some groups felt that accepting the scheme would make it more difficult to establish a Jewish state in Palestine, the African land was described as an "ante-chamber to the Holy Land". It was decided to send a commission to investigate the proposed land by 295 to 177 votes, with 132 abstaining. The following year, Congress sent a delegation to inspect the plateau. A temperate climate due to its high elevation, was thought to be suitable for European settlement. However, the area was populated by a large number of Maasai, who did not seem to favour an influx of Europeans. Furthermore, the delegation found it to be filled with lions and other animals.

After Herzl died in 1904, the Congress decided on the fourth day of its seventh session in July 1905 to decline the British offer and, according to Adam Rovner, "direct all future settlement efforts solely to Palestine". Israel Zangwill's Jewish Territorialist Organization aimed for a Jewish state anywhere, having been established in 1903 in response to the Uganda Scheme, was supported by a number of the Congress's delegates. Following the vote, which had been proposed by Max Nordau, Zangwill charged Nordau that he “will be charged before the bar of history,” and his supporters blamed the Russian voting bloc of Menachem Ussishkin for the outcome of the vote.

The subsequent departure of the JTO from the Zionist Organization had little impact. The Zionist Socialist Workers Party was also an organization that favored the idea of a Jewish territorial autonomy outside of Palestine.

As an alternative to Zionism, Soviet authorities established a Jewish Autonomous Oblast in 1934, which remains extant as the only autonomous oblast of Russia.

Balfour Declaration and the Palestine Mandate

Lobbying by Russian Jewish immigrant Chaim Weizmann, together with fear that American Jews would encourage the US to support Germany in the war against Russia, culminated in the British government's Balfour Declaration of 1917.

It endorsed the creation of a Jewish homeland in Palestine, as follows:

His Majesty's government view with favour the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people, and will use their best endeavours to facilitate the achievement of this object, it being clearly understood that nothing shall be done which may prejudice the civil and religious rights of existing non-Jewish communities in Palestine, or the rights and political status enjoyed by Jews in any other country.

In 1922, the League of Nations adopted the declaration, and granted to Britain the Palestine Mandate:

The Mandate will secure the establishment of the Jewish national home ... and the development of self-governing institutions, and also safeguard the civil and religious rights of all the inhabitants of Palestine, irrespective of race and religion.

Weizmann's role in obtaining the Balfour Declaration led to his election as the Zionist movement's leader. He remained in that role until 1948, and then was elected as the first President of Israel after the nation gained independence.

A number of high-level representatives of the international Jewish women's community participated in the First World Congress of Jewish Women, which was held in Vienna, Austria, in May 1923. One of the main resolutions was: "It appears ... to be the duty of all Jews to co-operate in the social-economic reconstruction of Palestine and to assist in the settlement of Jews in that country."

Jewish migration to Palestine and widespread Jewish land purchases from feudal landlords contributed to landlessness among Palestinian Arabs, fueling unrest. Riots erupted in Palestine in 1920, 1921 and 1929, in which both Jews and Arabs were killed. Britain was responsible for the Palestinian mandate and, after the Balfour Declaration, it supported Jewish immigration in principle. But, in response to the violent events noted above, the Peel Commission published a report proposing new provisions and restrictions in Palestine.

In 1927, Ukrainian Jew Yitzhak Lamdan wrote an epic poem titled Masada to reflect the plight of the Jews, calling for a "last stand". In 1941, Theodore Newman Kaufman published Germany Must Perish! which argued that only the dismemberment of Germany would lead to world peace. Anti-German articles, such as the Daily Express calling for an "Anti-Nazi boycott", in response to German antisemitism were published during Adolf Hitler's rise, as well. This has given birth to the conspiracy theory that Jews started the holocaust, although the Nazi Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels was largely responsible for ignoring the patriotic Jew, and for instead promoting anti-German materials as "evidence" that the Jews needed to be eradicated.

Rise of Hitler

In 1933, Hitler came to power in Germany, and in 1935 the Nuremberg Laws made German Jews (and later Austrian and Czech Jews) stateless refugees. Similar rules were applied by the many Nazi allies in Europe. The subsequent growth in Jewish migration and the impact of Nazi propaganda aimed at the Arab world led to the 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine. Britain established the Peel Commission to investigate the situation. The commission did not consider the situation of Jews in Europe but called for a two-state solution and compulsory transfer of populations. Britain rejected this solution and instead implemented the White Paper of 1939. This planned to end Jewish immigration by 1944 and to allow no more than 75,000 additional Jewish migrants. At the end of the five-year period in 1944, only 51,000 of the 75,000 immigration certificates provided for had been utilized, and the British offered to allow immigration to continue beyond cutoff date of 1944, at a rate of 1500 per month, until the remaining quota was filled. According to Arieh Kochavi, at the end of the war, the Mandatory Government had 10,938 certificates remaining and gives more details about government policy at the time. The British maintained the policies of the 1939 White Paper until the end of the Mandate.

The growth of the Jewish community in Palestine and the devastation of European Jewish life sidelined the World Zionist Organization. The Jewish Agency for Palestine under the leadership of David Ben-Gurion increasingly dictated policy with support from American Zionists who provided funding and influence in Washington, D.C., including via the highly effective American Palestine Committee.

During World War II, as the horrors of the Holocaust became known, the Zionist leadership formulated the One Million Plan, a reduction from Ben-Gurion's previous target of two million immigrants. Following the end of the war, a massive wave of stateless Jews, mainly Holocaust survivors, began migrating to Palestine in small boats in defiance of British rules. The Holocaust united much of the rest of world Jewry behind the Zionist project. The British either imprisoned these Jews in Cyprus or sent them to the British-controlled Allied Occupation Zones in Germany. The British, having faced the 1936–1939 Arab revolt against mass Jewish immigration into Palestine, were now facing opposition by Zionist groups in Palestine for subsequent restrictions. In January 1946 the Anglo-American Committee of Inquiry was a joint British and American committee set up to examine the political, economic and social conditions in Palestine as they bore upon the problem of Jewish immigration and settlement and the well-being of the peoples living there; to consult representatives of Arabs and Jews, and to make other recommendations 'as necessary' for an interim handling of these problems as well as for their eventual solution. Following the failure of the 1946–47 London Conference on Palestine, at which the United States refused to support the British leading to both the Morrison–Grady Plan and the Bevin Plan being rejected by all parties, the British decided to refer the question to the UN on February 14, 1947.

Post-World War II

With the German invasion of the USSR in 1941, Stalin reversed his long-standing opposition to Zionism, and tried to mobilize worldwide Jewish support for the Soviet war effort. A Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee was set up in Moscow. Many thousands of Jewish refugees fled the Nazis and entered the Soviet Union during the war, where they reinvigorated Jewish religious activities and opened new synagogues. In May 1947 Soviet Deputy Foreign Minister Andrei Gromyko told the United Nations that the USSR supported the partition of Palestine into a Jewish and an Arab state. The USSR formally voted that way in the UN in November 1947. However once Israel was established, Stalin reversed positions, favoured the Arabs, arrested the leaders of the Jewish Anti-Fascist Committee, and launched attacks on Jews in the USSR.

In 1947, the United Nations Special Committee on Palestine recommended that western Palestine should be partitioned into a Jewish state, an Arab state and a UN-controlled territory, Corpus separatum, around Jerusalem. This partition plan was adopted on November 29, 1947, with UN GA Resolution 181, 33 votes in favor, 13 against, and 10 abstentions. The vote led to celebrations in Jewish communities and protests in Arab communities throughout Palestine. Violence throughout the country, previously a Jewish insurgency against the British, with some sporadic Jewish-Arab fighting, spiralled into the 1947–1949 Palestine war. The conflict led to an exodus of about 711,000 Palestinian Arabs, known in Arabic as al-Nakba ("the Catastrophe"). More than a quarter had already fled prior to the declaration of the State of Israel and the start of the 1948 Arab–Israeli War. Later, a series of laws passed by the first Israeli government prevented Palestinians from returning to their homes, or claiming their property. They and many of their descendants remain refugees. The flight and expulsion of the Palestinians has since been widely, and controversially, described as having involved ethnic cleansing. According to a growing consensus between Israeli and Palestinian historians, expulsion and destruction of villages played a part in the origin of the Palestinian refugees. While British scholar Efraim Karsh, states that most of the Arabs who fled left of their own accord or were pressured to leave by their fellow Arabs, despite Israeli attempts to convince them to stay many historians dismiss this claim as devoid of evidence, Morris, with others of the New Historians school, concur that Arab instigation was not the major cause of the refugees' flight. and state that the major cause of Palestinian flight was instead military actions by the Israeli Defence Force and fear of them and that Arab instigation can only explain a small part of the exodus and not a large part of it.

Since the creation of the State of Israel, the World Zionist Organization has functioned mainly as an organization dedicated to assisting and encouraging Jews to migrate to Israel. It has provided political support for Israel in other countries but plays little role in internal Israeli politics. The movement's major success since 1948 was in providing logistical support for migrating Jews and, most importantly, in assisting Soviet Jews in their struggle with the authorities over the right to leave the USSR and to practice their religion in freedom, and the exodus of 850,000 Jews from the Arab world, mostly to Israel. In 1944–45, Ben-Gurion described the One Million Plan to foreign officials as being the "primary goal and top priority of the Zionist movement." The immigration restrictions of the British White Paper of 1939 meant that such a plan could not be put into large scale effect until the Israeli Declaration of Independence in May 1948. The new country's immigration policy had some opposition within the new Israeli government, such as those who argued that there was "no justification for organizing large-scale emigration among Jews whose lives were not in danger, particularly when the desire and motivation were not their own" as well as those who argued that the absorption process caused "undue hardship". However, the force of Ben-Gurion's influence and insistence ensured that his immigration policy was carried out.

Types

| Country/Region | Members | Delegates |

|---|---|---|

| Poland | 299,165 | 109 |

| USA | 263,741 | 114 |

| Palestine | 167,562 | 134 |

| Romania | 60,013 | 28 |

| United Kingdom | 23,513 | 15 |

| South Africa | 22,343 | 14 |

| Canada | 15,220 | 8 |

The multi-national, worldwide Zionist movement is structured on representative democratic principles. Congresses are held every four years (they were held every two years before the Second World War) and delegates to the congress are elected by the membership. Members are required to pay dues known as a shekel. At the congress, delegates elect a 30-man executive council, which in turn elects the movement's leader. The movement was democratic from its inception and women had the right to vote.

Until 1917, the World Zionist Organization pursued a strategy of building a Jewish National Home through persistent small-scale immigration and the founding of such bodies as the Jewish National Fund (1901 – a charity that bought land for Jewish settlement) and the Anglo-Palestine Bank (1903 – provided loans for Jewish businesses and farmers). In 1942, at the Biltmore Conference, the movement included for the first time an express objective of the establishment of a Jewish state in the Land of Israel.

The 28th Zionist Congress, meeting in Jerusalem in 1968, adopted the five points of the "Jerusalem Program" as the aims of Zionism today. They are:

- Unity of the Jewish People and the centrality of Israel in Jewish life

- Ingathering of the Jewish People in its historic homeland, Eretz Israel, through Aliyah from all countries

- Strengthening of the State of Israel, based on the prophetic vision of justice and peace

- Preservation of the identity of the Jewish People through fostering of Jewish and Hebrew education, and of Jewish spiritual and cultural values

- Protection of Jewish rights everywhere

Since the creation of modern Israel, the role of the movement has declined. It is now a peripheral factor in Israeli politics, though different perceptions of Zionism continue to play roles in Israeli and Jewish political discussion.

Labor Zionism

Labor Zionism originated in Eastern Europe. Socialist Zionists believed that centuries of oppression in antisemitic societies had reduced Jews to a meek, vulnerable, despairing existence that invited further antisemitism, a view originally stipulated by Theodor Herzl. They argued that a revolution of the Jewish soul and society was necessary and achievable in part by Jews moving to Israel and becoming farmers, workers, and soldiers in a country of their own. Most socialist Zionists rejected the observance of traditional religious Judaism as perpetuating a "Diaspora mentality" among the Jewish people, and established rural communes in Israel called "kibbutzim". The kibbutz began as a variation on a "national farm" scheme, a form of cooperative agriculture where the Jewish National Fund hired Jewish workers under trained supervision. The kibbutzim were a symbol of the Second Aliyah in that they put great emphasis on communalism and egalitarianism, representing Utopian socialism to a certain extent. Furthermore, they stressed self-sufficiency, which became an essential aspect of Labor Zionism. Though socialist Zionism draws its inspiration and is philosophically founded on the fundamental values and spirituality of Judaism, its progressive expression of that Judaism has often fostered an antagonistic relationship with Orthodox Judaism.

Labor Zionism became the dominant force in the political and economic life of the Yishuv during the British Mandate of Palestine and was the dominant ideology of the political establishment in Israel until the 1977 election when the Israeli Labor Party was defeated. The Israeli Labor Party continues the tradition, although the most popular party in the kibbutzim is Meretz. Labor Zionism's main institution is the Histadrut (general organisation of labor unions), which began by providing strikebreakers against a Palestinian worker's strike in 1920 and until 1970s was the largest employer in Israel after the Israeli government.

Liberal Zionism

General Zionism (or Liberal Zionism) was initially the dominant trend within the Zionist movement from the First Zionist Congress in 1897 until after the First World War. General Zionists identified with the liberal European middle class to which many Zionist leaders such as Herzl and Chaim Weizmann aspired. Liberal Zionism, although not associated with any single party in modern Israel, remains a strong trend in Israeli politics advocating free market principles, democracy and adherence to human rights. Their political arm was one of the ancestors of the modern-day Likud. Kadima, the main centrist party during the 2000s that split from Likud and is now defunct, however, did identify with many of the fundamental policies of Liberal Zionist ideology, advocating among other things the need for Palestinian statehood in order to form a more democratic society in Israel, affirming the free market, and calling for equal rights for Arab citizens of Israel. In 2013, Ari Shavit suggested that the success of the then-new Yesh Atid party (representing secular, middle-class interests) embodied the success of "the new General Zionists."

Dror Zeigerman writes that the traditional positions of the General Zionists—"liberal positions based on social justice, on law and order, on pluralism in matters of State and Religion, and on moderation and flexibility in the domain of foreign policy and security"—are still favored by important circles and currents within certain active political parties.

Philosopher Carlo Strenger describes a modern-day version of Liberal Zionism (supporting his vision of "Knowledge-Nation Israel"), rooted in the original ideology of Herzl and Ahad Ha'am, that stands in contrast to both the romantic nationalism of the right and the Netzah Yisrael of the ultra-Orthodox. It is marked by a concern for democratic values and human rights, freedom to criticize government policies without accusations of disloyalty, and rejection of excessive religious influence in public life. "Liberal Zionism celebrates the most authentic traits of the Jewish tradition: the willingness for incisive debate; the contrarian spirit of davka; the refusal to bow to authoritarianism." Liberal Zionists see that "Jewish history shows that Jews need and are entitled to a nation-state of their own. But they also think that this state must be a liberal democracy, which means that there must be strict equality before the law independent of religion, ethnicity or gender."

Revisionist Zionism

Revisionist Zionists, led by Ze'ev Jabotinsky, developed what became known as Nationalist Zionism, whose guiding principles were outlined in the 1923 essay Iron Wall. In 1935 the Revisionists left the World Zionist Organization because it refused to state that the creation of a Jewish state was an objective of Zionism.

Jabotinsky believed that,

Zionism is a colonising adventure and it therefore stands or falls by the question of armed force. It is important to build, it is important to speak Hebrew, but, unfortunately, it is even more important to be able to shoot—or else I am through with playing at colonization.

and that

Although the Jews originated in the East, they belonged to the West culturally, morally, and spiritually. Zionism was conceived by Jabotinsky not as the return of the Jews to their spiritual homeland but as an offshoot or implant of Western civilization in the East. This worldview translated into a geostrategic conception in which Zionism was to be permanently allied with European colonialism against all the Arabs in the eastern Mediterranean.

The revisionists advocated the formation of a Jewish Army in Palestine to force the Arab population to accept mass Jewish migration.

Supporters of Revisionist Zionism developed the Likud Party in Israel, which has dominated most governments since 1977. It advocates Israel's maintaining control of the West Bank, including East Jerusalem, and takes a hard-line approach in the Arab–Israeli conflict. In 2005, the Likud split over the issue of creation of a Palestinian state in the occupied territories. Party members advocating peace talks helped form the Kadima Party.

Religious Zionism

Religious Zionism is an ideology that combines Zionism and observant Judaism. Before the establishment of the State of Israel, Religious Zionists were mainly observant Jews who supported Zionist efforts to build a Jewish state in the Land of Israel.

After the Six-Day War and the capture of the West Bank, a territory referred to in Jewish terms as Judea and Samaria, right-wing components of the Religious Zionist movement integrated nationalist revindication and evolved into Neo-Zionism. Their ideology revolves around three pillars: the Land of Israel, the People of Israel and the Torah of Israel.

Green Zionism

Green Zionism is a branch of Zionism primarily concerned with the environment of Israel. The only specifically environmentalist Zionist party is the Green Zionist Alliance.

Post-Zionism

During the last quarter of the 20th century, classic nationalism in Israel declined. This led to the rise of post-Zionism. Post-Zionism asserts that Israel should abandon the concept of a "state of the Jewish people" and strive to be a state of all its citizens or a binational state where Arabs and Jews live together while enjoying some type of autonomy.

Non-Jewish support

Political support for the Jewish return to the Land of Israel predates the formal organization of Jewish Zionism as a political movement. In the 19th century, advocates of the restoration of the Jews to the Holy Land were called Restorationists. The return of the Jews to the Holy Land was widely supported by such eminent figures as Queen Victoria, Napoleon Bonaparte, King Edward VII, President John Adams of the United States, General Smuts of South Africa, President Masaryk of Czechoslovakia, philosopher and historian Benedetto Croce from Italy, Henry Dunant (founder of the Red Cross and author of the Geneva Conventions), and scientist and humanitarian Fridtjof Nansen from Norway.

The French government, through Minister M. Cambon, formally committed itself to "... the renaissance of the Jewish nationality in that Land from which the people of Israel were exiled so many centuries ago."

In China, top figures of the Nationalist government, including Sun Yat-sen, expressed their sympathy with the aspirations of the Jewish people for a National Home.

Christian Zionism

Some Christians actively supported the return of Jews to Palestine even prior to the rise of Zionism, as well as subsequently. Anita Shapira, a history professor emerita at Tel Aviv University, suggests that evangelical Christian restorationists of the 1840s 'passed this notion on to Jewish circles'. Evangelical Christian anticipation of and political lobbying within the UK for Restorationism was widespread in the 1820s and common beforehand. It was common among the Puritans to anticipate and frequently to pray for a Jewish return to their homeland.

One of the principal Protestant teachers who promoted the biblical doctrine that the Jews would return to their national homeland was John Nelson Darby. His doctrine of dispensationalism is credited with promoting Zionism, following his 11 lectures on the hopes of the church, the Jew and the gentile given in Geneva in 1840. However, others like C H Spurgeon, both Horatius and Andrew Bonar, Robert Murray M'Chyene, and J C Ryle were among a number of prominent proponents of both the importance and significance of a Jewish return, who were not dispensationalist. Pro-Zionist views were embraced by many evangelicals and also affected international foreign policy.

The Russian Orthodox ideologue Hippolytus Lutostansky, also known as the author of multiple antisemitic tracts, insisted in 1911 that Russian Jews should be "helped" to move to Palestine "as their rightful place is in their former kingdom of Palestine".

Notable early supporters of Zionism include British Prime Ministers David Lloyd George and Arthur Balfour, American President Woodrow Wilson and British Major-General Orde Wingate, whose activities in support of Zionism led the British Army to ban him from ever serving in Palestine. According to Charles Merkley of Carleton University, Christian Zionism strengthened significantly after the Six-Day War of 1967, and many dispensationalist and non-dispensationalist evangelical Christians, especially Christians in the United States, now strongly support Zionism.

Martin Luther King Jr. was a strong supporter of Israel and Zionism, although the Letter to an Anti-Zionist Friend is a work falsely attributed to him.

In the last years of his life, the founder of the Latter Day Saint movement, Joseph Smith, declared, "the time for Jews to return to the land of Israel is now." In 1842, Smith sent Orson Hyde, an Apostle of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, to Jerusalem to dedicate the land for the return of the Jews.

Some Arab Christians publicly supporting Israel include US author Nonie Darwish, and former Muslim Magdi Allam, author of Viva Israele, both born in Egypt. Brigitte Gabriel, a Lebanese-born Christian US journalist and founder of the American Congress for Truth, urges Americans to "fearlessly speak out in defense of America, Israel and Western civilization".

Muslim Zionism

Muslims who have publicly defended Zionism include Tawfik Hamid, Islamic thinker and reformer and former member of al-Gama'a al-Islamiyya, an Islamist militant group that is designated as a terrorist organization by the United States and European Union, Sheikh Prof. Abdul Hadi Palazzi, Director of the Cultural Institute of the Italian Islamic Community and Tashbih Sayyed, a Pakistani-American scholar, journalist, and author.

On occasion, some non-Arab Muslims such as some Kurds and Berbers have also voiced support for Zionism.

While most Israeli Druze identify as ethnically Arab, today, tens of thousands of Israeli Druze belong to "Druze Zionist" movements.

During the Palestine Mandate era, As'ad Shukeiri, a Muslim scholar ('alim) of the Acre area, and the father of PLO founder Ahmad Shukeiri, rejected the values of the Palestinian Arab national movement and was opposed to the anti-Zionist movement. He met routinely with Zionist officials and had a part in every pro-Zionist Arab organization from the beginning of the British Mandate, publicly rejecting Mohammad Amin al-Husayni's use of Islam to attack Zionism.

Some Indian Muslims have also expressed opposition to Islamic anti-Zionism. In August 2007, a delegation of the All India Organization of Imams and mosques led by its president Maulana Jamil Ilyas visited Israel. The meeting led to a joint statement expressing "peace and goodwill from Indian Muslims", developing dialogue between Indian Muslims and Israeli Jews, and rejecting the perception that the Israeli–Palestinian conflict is of a religious nature. The visit was organized by the American Jewish Committee. The purpose of the visit was to promote meaningful debate about the status of Israel in the eyes of Muslims worldwide and to strengthen the relationship between India and Israel. It is suggested that the visit could "open Muslim minds across the world to understand the democratic nature of the state of Israel, especially in the Middle East".

Hindu support for Zionism

After Israel's creation in 1948, the Indian National Congress government opposed Zionism. Some writers have claimed that this was done in order to get more Muslim votes in India (where Muslims numbered over 30 million at the time). However, conservative Hindu nationalists, led by the Sangh Parivar, openly supported Zionism, as did Hindu Nationalist intellectuals like Vinayak Damodar Savarkar and Sita Ram Goel. Zionism, seen as a national liberation movement for the repatriation of the Jewish people to their homeland then under British colonial rule, appealed to many Hindu Nationalists, who viewed their struggle for independence from British rule and the Partition of India as national liberation for long-oppressed Hindus.

An international opinion survey has shown that India is the most pro-Israel country in the world. In more current times, conservative Indian parties and organizations tend to support Zionism. This has invited attacks on the Hindutva movement by parts of the Indian left opposed to Zionism, and allegations that Hindus are conspiring with the "Jewish Lobby."

Anti-Zionism

Zionism is opposed by a wide variety of organizations and individuals. Among those opposing Zionism were and are some secular Jews, some branches of Judaism (Satmar Hasidim and Neturei Karta), the former Soviet Union, many in the Muslim world, and Palestinians. Reasons for opposing Zionism are varied, and they include: the perception that land confiscations are unfair; expulsions of Palestinians; violence against Palestinians; and alleged racism. Arab states in particular strongly oppose Zionism, which they believe is responsible for the 1948 Palestinian exodus. The preamble of the African Charter on Human and Peoples' Rights, which has been ratified by 53 African countries as of 2014, includes an undertaking to eliminate Zionism together with other practices including colonialism, neo-colonialism, apartheid, "aggressive foreign military bases" and all forms of discrimination.

Zionism was also opposed for other reasons by some Jews even before the establishment of the state of Israel because "Zionism constitutes a danger, both spiritual and physical, to the existence of our people".

In 1945 US President Franklin D Roosevelt met with king Ibn Saud of Saudi Arabia. Ibn Saud pointed out that it was Germany who had committed crimes against the Jews and so Germany should be punished. Palestinian Arabs had done no harm to European Jews and did not deserve to be punished by losing their land. Roosevelt on return to the US concluded that Israel "could only be established and maintained by force."

Catholic Church and Zionism

The initial response of the Catholic Church seemed to be one of strong opposition to Zionism. Shortly after the 1897 Basel Conference, the semi-official Vatican periodical (edited by the Jesuits) Civiltà Cattolica gave its biblical-theological judgement on political Zionism: "1827 years have passed since the prediction of Jesus of Nazareth was fulfilled ... that [after the destruction of Jerusalem] the Jews would be led away to be slaves among all the nations and that they would remain in the dispersion [diaspora, galut] until the end of the world." The Jews should not be permitted to return to Palestine with sovereignty: "According to the Sacred Scriptures, the Jewish people must always live dispersed and vagabondo [vagrant, wandering] among the other nations, so that they may render witness to Christ not only by the Scriptures ... but by their very existence".

Nonetheless, Theodore Herzl travelled to Rome in late January 1904, after the sixth Zionist Congress (August 1903) and six months before his death, looking for some kind of support. On January 22, Herzl first met the Papal Secretary of State, Cardinal Rafael Merry del Val. According to Herzl's private diary notes, the Cardinal's interpretation of the history of Israel was the same as that of the Catholic Church, but he also asked for the conversion of the Jews to Catholicism. Three days later, Herzl met Pope Pius X, who replied to his request of support for a Jewish return to Israel in the same terms, saying that "we are unable to favor this movement. We cannot prevent the Jews from going to Jerusalem, but we could never sanction it ... The Jews have not recognized our Lord, therefore we cannot recognize the Jewish people." In 1922, the same periodical published a piece by its Viennese correspondent, "anti-Semitism is nothing but the absolutely necessary and natural reaction to the Jews' arrogance... Catholic anti-Semitism – while never going beyond the moral law – adopts all necessary means to emancipate the Christian people from the abuse they suffer from their sworn enemy". This initial attitude changed over the next 50 years, until 1997, when at the Vatican symposium of that year, Pope John Paul II rejected the Christian roots of antisemitism, stating that "... the wrong and unjust interpretations of the New Testament relating to the Jewish people and their supposed guilt [in Christ's death] circulated for too long, engendering sentiments of hostility toward this people."

Characterization as colonialism or ethnic cleansing

Zionism has been characterized as colonialism, and Zionism has been criticized for promoting unfair confiscation of land, involving the expulsion of, and causing violence towards, the Palestinians. The characterization of Zionism as colonialism has been described by, among others, Nur Masalha, Gershon Shafir, Michael Prior, Ilan Pappe, and Baruch Kimmerling.

Others, such as Shlomo Avineri and Mitchell Bard, view Zionism not as a colonialist movement, but as a national movement that is contending with the Palestinian one. South African rabbi David Hoffman rejected the claim that Zionism is a 'settler-colonial undertaking' and instead characterized Zionism as a national program of affirmative action, adding that there is unbroken Jewish presence in Israel back to antiquity.

Noam Chomsky, John P. Quigly, Nur Masalha, and Cheryl Rubenberg have criticized Zionism, saying that it unfairly confiscates land and expels Palestinians.

Isaac Deutscher has called Israelis the 'Prussians of the Middle East', who have achieved a 'totsieg', a 'victorious rush into the grave' as a result of dispossessing 1.5 million Palestinians. Israel had become the 'last remaining colonial power' of the twentieth century.

Edward Said and Michael Prior claim that the notion of expelling the Palestinians was an early component of Zionism, citing Herzl's diary from 1895 which states "we shall endeavour to expel the poor population across the border unnoticed—the process of expropriation and the removal of the poor must be carried out discreetly and circumspectly." This quotation has been critiqued by Efraim Karsh for misrepresenting Herzl's purpose. He describes it as "a feature of Palestinian propaganda", writing that Herzl was referring to the voluntary resettlement of squatters living on land purchased by Jews, and that the full diary entry stated, "It goes without saying that we shall respectfully tolerate persons of other faiths and protect their property, their honor, and their freedom with the harshest means of coercion. This is another area in which we shall set the entire world a wonderful example … Should there be many such immovable owners in individual areas [who would not sell their property to us], we shall simply leave them there and develop our commerce in the direction of other areas which belong to us." Derek Penslar says that Herzl may have been considering either South America or Palestine when he wrote the diary entry about expropriation. According to Walter Laqueur, although many Zionists proposed transfer, it was never official Zionist policy and in 1918 Ben-Gurion "emphatically rejected" it.

Ilan Pappe argued that Zionism results in ethnic cleansing. This view diverges from other New Historians, such as Benny Morris, who accept the Palestinian exodus narrative but place it in the context of war, not ethnic cleansing. When Benny Morris was asked about the Expulsion of Palestinians from Lydda and Ramle, he responded "There are circumstances in history that justify ethnic cleansing. I know that this term is completely negative in the discourse of the 21st century, but when the choice is between ethnic cleansing and genocide—the annihilation of your people—I prefer ethnic cleansing."

Saleh Abdel Jawad, Nur Masalha, Michael Prior, Ian Lustick, and John Rose have criticized Zionism for having been responsible for violence against Palestinians, such as the Deir Yassin massacre, Sabra and Shatila massacre, and Cave of the Patriarchs massacre.

In 1938, Mahatma Gandhi rejected Zionism, saying that the establishment of a Jewish national home in Palestine is a religious act and therefore must not be performed by force, comparing it to the Partition of India into Hindu and Muslim countries. He wrote, "Palestine belongs to the Arabs in the same sense that England belongs to the English or France to the French. It is wrong and inhuman to impose the Jews on the Arabs ... Surely it would be a crime against humanity to reduce the proud Arabs so that Palestine can be restored to the Jews partly or wholly as their national home ... They can settle in Palestine only by the goodwill of the Arabs. They should seek to convert the Arab heart." Gandhi later told American journalist Louis Fischer in 1946 that "Jews have a good case in Palestine. If the Arabs have a claim to Palestine, the Jews have a prior claim".

Characterization as racist

David Ben-Gurion stated that "There will be no discrimination among citizens of the Jewish state on the basis of race, religion, sex, or class." Likewise, Vladimir Jabotinsky avowed "the minority will not be rendered defenseless... [the] aim of democracy is to guarantee that the minority too has influence on matters of state policy."

However, critics of Zionism consider it a colonialist or racist movement. According to historian Avi Shlaim, throughout its history up to present day, Zionism "is replete with manifestations of deep hostility and contempt towards the indigenous population." Shlaim balances this by pointing out that there have always been individuals within the Zionist movement that have criticized such attitudes. He cites the example of Ahad Ha'am, who after visiting Palestine in 1891, published a series of articles criticizing the aggressive behaviour and political ethnocentrism of Zionist settlers. Ha'am wrote that the Zionists "behave towards the Arabs with hostility and cruelty, trespass unjustly upon their boundaries, beat them shamefully without reason and even brag about it, and nobody stands to check this contemptible and dangerous tendency" and that they believed that "the only language that the Arabs understand is that of force." Some criticisms of Zionism claim that Judaism's notion of the "chosen people" is the source of racism in Zionism, despite, according to Gustavo Perednik, that being a religious concept unrelated to Zionism.

In December 1973, the UN passed a series of resolutions condemning South Africa and included a reference to an "unholy alliance between Portuguese colonialism, Apartheid and Zionism." At the time there was little cooperation between Israel and South Africa, although the two countries would develop a close relationship during the 1970s. Parallels have also been drawn between aspects of South Africa's apartheid regime and certain Israeli policies toward the Palestinians, which are seen as manifestations of racism in Zionist thinking.

In 1975 the UN General Assembly passed Resolution 3379, which said "Zionism is a form of racism and racial discrimination". According to the resolution, "any doctrine of racial differentiation of superiority is scientifically false, morally condemnable, socially unjust, and dangerous." The resolution named the occupied territory of Palestine, Zimbabwe, and South Africa as examples of racist regimes. Resolution 3379 was pioneered by the Soviet Union and passed with numerical support from Arab and African states amidst accusations that Israel was supportive of the apartheid regime in South Africa. The resolution was robustly criticised by the US representative, Daniel Patrick Moynihan as an 'obscenity' and a 'harm ... done to the United Nations'. 'In 1991 the resolution was repealed with UN General Assembly Resolution 46/86, after Israel declared that it would only participate in the Madrid Conference of 1991 if the resolution were revoked.

The United States ... does not acknowledge, it will not abide by, it will never acquiesce in this infamous act… The lie is that Zionism is a form of racism. The overwhelmingly clear truth is that it is not.

— Daniel Patrick Moynihan, speaking in the UN General Assembly after Resolution 3379 was passed, 1975.

Arab countries sought to associate Zionism with racism in connection with a 2001 UN conference on racism, which took place in Durban, South Africa, which caused the United States and Israel to walk away from the conference as a response. The final text of the conference did not connect Zionism with racism. A human rights forum arranged in connection with the conference, on the other hand, did equate Zionism with racism and censured Israel for what it called "racist crimes, including acts of genocide and ethnic cleansing".

Supporters of Zionism, such as Chaim Herzog, argue that the movement is non-discriminatory and contains no racist aspects.

Haredi Judaism and Zionism

Many Haredi Orthodox organizations oppose Zionism; they view Zionism as a secular movement. They reject nationalism as a doctrine and consider Judaism to be first and foremost a religion that is not dependent on a state. However, some Haredi movements (such as Shas since 2010) do openly affiliate with the Zionist movement.

Haredi rabbis do not consider Israel to be a halachic Jewish state because it has secular government. But they take responsibility for ensuring that Jews maintain religious ideals and, since most Israeli citizens are Jews, they pursue this agenda within Israel. Others reject any possibility of a Jewish state, since according to them a Jewish state is completely forbidden by Jewish religious law. In their view a Jewish state is an oxymoron.

Two Haredi parties run candidates in Israeli elections. They are sometimes associated with views that could be regarded as nationalist or Zionist. They prefer coalitions with more nationalist Zionist parties, probably because these are more interested in enhancing the Jewish nature of the Israeli state. The Sephardi-Orthodox party Shas rejected association with the Zionist movement; however, in 2010 it joined the World Zionist Organization. Its voters generally identify as Zionist, and Knesset members frequently pursue what others might consider a Zionist agenda. Shas has supported territorial compromise with the Arabs and Palestinians, but it generally opposes compromise over Jewish holy sites.

The non-Hasidic or 'Lithuanian' Haredi Ashkenazi world is represented by the Ashkenazi Agudat Israel/UTJ party. It has always avoided association with the Zionist movement and usually avoids voting on or discussing issues related to peace, because its members do not serve in the army. The party works to ensure that Israel and Israeli law are in tune with the halacha, on issues such as Shabbat rest. The rabbinical leaders of the so-called Litvishe world in current and past generations, such as Rabbi Elazar Menachem Shach and Rabbi Avigdor Miller, are strongly opposed to all forms of Zionism, religious and secular. But they allow members to participate in Israeli political life, including both passive and active participation in elections.

Many other Hasidic groups in Jerusalem, most famously the Satmar Hasidim, as well as the larger movement they are part of, the Edah HaChareidis, are strongly anti-Zionist. One of the best known Hasidic opponents of all forms of modern political Zionism was Hungarian rebbe and Talmudic scholar Joel Teitelbaum. In his view, the current State of Israel is contrariwise to Judaism, because it was founded by people who included some anti-religious personalities, and were in apparent violation of the traditional notion that Jews should wait for the Jewish Messiah.

Teitelbaum referred to core citations from classical Judaic sources in his arguments against modern Zionism; specifically a passage in the Talmud, in which Rabbi Yosi b'Rebbi Hanina explains (Kesubos 111a) that the Lord imposed "Three Oaths" on the nation of Israel: a) Israel should not return to the Land together, by force; b) Israel should not rebel against the other nations; and c) The nations should not subjugate Israel too harshly. According to Teitelbaum, the second oath is relevant concerning the subsequent wars fought between Israel and Arab nations.

Other opponent groups among the Edah HaChareidis were Dushinsky, Toldos Aharon, Toldos Avrohom Yitzchok, Spinka, and others. They number in the tens of thousands in Jerusalem, and hundreds of thousands worldwide.

The Neturei Karta, an Orthodox Haredi religious movement, strongly oppose Zionism, considering Israel a "racist regime". They are viewed as a cult on the "farthest fringes of Judaism" by most mainstream Jews; the Jewish Virtual Library puts their numbers at 5,000, but the Anti-Defamation League estimates that fewer than 100 members of the community actually take part in anti-Israel activism. The movement equates Zionism to Nazism, believes that Zionist ideology is contrary to the teachings of the Torah, and also blames Zionism for increases in antisemitism. Members of Neturei Karta have a long history of extremist statements and support for notable anti-Semites and Islamic extremists.

The Chabad-Lubavitch Hasidic movement traditionally did not identify as Zionist, but has adopted a Zionist agenda since the late 20th century, opposing any territorial compromise in Israel.

Anti-Zionism or antisemitism

Some critics of anti-Zionism have argued that opposition to Zionism can be hard to distinguish from antisemitism, and that criticism of Israel may be used as an excuse to express viewpoints that might otherwise be considered antisemitic. Other scholars argue that certain forms of opposition to Zionism constitute antisemitism. A number of scholars have argued that opposition to Zionism or the State of Israel's policies at the more extreme fringes often overlaps with antisemitism. In the Arab world, the words "Jew" and "Zionist" are often used interchangeably. To avoid accusations of antisemitism, the Palestine Liberation Organization has historically avoided using the word "Jewish" in favor of using "Zionist," though PLO officials have sometimes slipped.

Some antisemites have alleged that Zionism was, or is, part of a Jewish plot to take control of the world. One particular version of these allegations, "The Protocols of the Elders of Zion" (subtitle "Protocols extracted from the secret archives of the central chancery of Zion") achieved global notability. The protocols are fictional minutes of an imaginary meeting by Jewish leaders of this plot. Analysis and proof of their fraudulent origin goes as far back as 1921. A 1920 German version renamed them "The Zionist Protocols". The protocols were extensively used as propaganda by the Nazis and remain widely distributed in the Arab world. They are referred to in the 1988 Hamas charter.

There are examples of anti-Zionists using accusations, slanders, imagery and tactics previously associated with antisemites. On October 21, 1973, the then-Soviet ambassador to the United Nations Yakov Malik declared: "The Zionists have come forth with the theory of the Chosen People, an absurd ideology." Similarly, an exhibit about Zionism and Israel in the former Museum of Religion and Atheism in Saint Petersburg designated the following as Soviet Zionist material: Jewish prayer shawls, tefillin and Passover Hagaddahs, even though these are all religious items used by Jews for thousands of years.

On the other hand, anti-Zionist writers such as Noam Chomsky, Norman Finkelstein, Michael Marder, and Tariq Ali have argued that the characterization of anti-Zionism as antisemitic is inaccurate, that it sometimes obscures legitimate criticism of Israel's policies and actions, and that it is sometimes used as a political ploy in order to stifle legitimate criticism of Israel.

- Linguist Noam Chomsky argues: "There have long been efforts to identify anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism in an effort to exploit anti-racist sentiment for political ends; "one of the chief tasks of any dialogue with the Gentile world is to prove that the distinction between anti-Semitism and anti-Zionism is not a distinction at all," Israeli diplomat Abba Eban argued, in a typical expression of this intellectually and morally disreputable position (Eban, Congress Bi-Weekly, March 30, 1973). But that no longer suffices. It is now necessary to identify criticism of Israeli policies as anti-Semitism — or in the case of Jews, as "self-hatred," so that all possible cases are covered." — Chomsky, 1989 "Necessary Illusions".

- Philosopher Michael Marder argues: "To deconstruct Zionism is ... to demand justice for its victims - not only for the Palestinians, who are suffering from it, but also for the anti-Zionist Jews, 'erased' from the officially consecrated account of Zionist history. By deconstructing its ideology, we shed light on the context it strives to repress and on the violence it legitimises with a mix of theological or metaphysical reasoning and affective appeals to historical guilt for the undeniably horrific persecution of Jewish people in Europe and elsewhere."

- American political scientist Norman Finkelstein argues that anti-Zionism and often just criticism of Israeli policies have been conflated with antisemitism, sometimes called new antisemitism for political gain: "Whenever Israel faces a public relations débâcle such as the Intifada or international pressure to resolve the Israel-Palestine conflict, American Jewish organizations orchestrate this extravaganza called the 'new anti-Semitism.' The purpose is several-fold. First, it is to discredit any charges by claiming the person is an anti-Semite. It's to turn Jews into the victims, so that the victims are not the Palestinians any longer. As people like Abraham Foxman of the ADL put it, the Jews are being threatened by a new holocaust. It's a role reversal — the Jews are now the victims, not the Palestinians. So it serves the function of discrediting the people leveling the charge. It's no longer Israel that needs to leave the Occupied Territories; it's the Arabs who need to free themselves of the anti-Semitism.

Marcus Garvey and Black Zionism

Zionist success in winning British support for the formation of a Jewish National Home in Palestine helped inspire the Jamaican Black nationalist Marcus Garvey to form a movement dedicated to returning Americans of African origin to Africa. During a speech in Harlem in 1920, Garvey stated: "other races were engaged in seeing their cause through—the Jews through their Zionist movement and the Irish through their Irish movement—and I decided that, cost what it might, I would make this a favorable time to see the Negro's interest through." Garvey established a shipping company, the Black Star Line, to allow Black Americans to emigrate to Africa, but for various reasons he failed in his endeavor.

Garvey helped inspire the Rastafari movement in Jamaica, the Black Jews and the African Hebrew Israelites of Jerusalem who initially moved to Liberia before settling in Israel.