Spacecraft concept illustration | |

| Mission type | Rotorcraft on Titan |

|---|---|

| Operator | NASA |

| COSPAR ID | |

| Website | https://dragonfly.jhuapl.edu/ |

| Mission duration | 10 years (planned) Science phase: 3.3 years |

| Spacecraft properties | |

| Spacecraft type | Rotorcraft lander |

| Manufacturer | Applied Physics Laboratory |

| Landing mass | ≈450 kg (990 lb) |

| Power | 70 watts (desired) from an MMRTG |

| Start of mission | |

| Launch date | June 2027 (planned) |

| Rocket | Atlas V 411 or equivalent performance (actual launch vehicle will be selected later) |

| Launch site | TBA |

| Contractor | TBA |

| Titan aircraft | |

| Landing date | 2034 |

| Landing site | Shangri-La dune fields |

| Distance flown | 8 km (5.0 mi) per flight (planned) |

| Instruments | |

| Dragonfly Mass Spectrometer (DraMS) Dragonfly Gamma-Ray and Neutron Spectrometer (DraGNS) Dragonfly Geophysics and Meteorology Package (DraGMet) | |

Dragonfly Mission Insignia | |

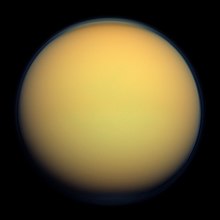

Dragonfly is a planned spacecraft and NASA mission, which will send a robotic rotorcraft to the surface of Titan, the largest moon of Saturn. It would be the first aircraft on Titan and is intended to make the first powered and fully controlled atmospheric flight on any moon, with the intention of studying prebiotic chemistry and extraterrestrial habitability. It will then use its vertical takeoffs and landings (VTOL) capability to move between exploration sites.

Titan is unique in having an abundant, complex, and diverse carbon-rich chemistry on the surface of a water-ice-dominated world with an interior water ocean, making it a high-priority target for astrobiology and origin of life studies. The mission was proposed in April 2017 to NASA's New Frontiers program by the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL), and was selected as one of two finalists (out of twelve proposals) in December 2017 to further refine the mission's concept. On 27 June 2019, Dragonfly was selected to become the fourth mission in the New Frontiers program.

Overview

Dragonfly is an astrobiology mission to Titan to assess its microbial habitability and study its prebiotic chemistry at various locations. Dragonfly will perform controlled flights and vertical takeoffs and landings between locations. The mission will involve flights to multiple different locations on the surface, which allows sampling of diverse regions and geological contexts.

Titan is a compelling astrobiology target because its surface contains abundant complex carbon-rich chemistry and because both liquid water and liquid hydrocarbons can occur on its surface, possibly forming a prebiotic primordial soup.

A successful flight of Dragonfly will make it the second rotorcraft to fly on a celestial body other than Earth, following the success of a Martian technology demonstration UAV helicopter, Ingenuity, which landed on Mars with the Perseverance rover on 18 February 2021 as part of the Mars 2020 mission and successfully achieved powered flight on 19 April 2021.

History

The initial Dragonfly conception took place over a dinner conversation between scientists Jason W. Barnes of Department of Physics, University of Idaho, (who had previously made the AVIATR proposal for a Titan aircraft) and Ralph Lorenz of Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, and it took 15 months to make it a detailed mission proposal. The principal investigator is Elizabeth Turtle, a planetary scientist at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory.

The Dragonfly mission builds on several earlier studies of Titan mobile aerial exploration, including the 2007 Titan Explorer Flagship study, which advocated a Montgolfier balloon for regional exploration, and AVIATR, an airplane concept considered for the Discovery program. The concept of a rotorcraft lander that flew on battery power, recharged during the 8-Earth-day Titan night from a radioisotope power source, was proposed by Lorenz in 2000. More recent discussion has included a 2014 Titan rotorcraft study by Larry Matthies, at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory, that would have a small rotorcraft deployed from a lander or a balloon. The hot-air balloon concepts would have used the heat from a radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG).

Leveraging proven rotorcraft systems and technologies, Dragonfly will use a multi-rotor vehicle to transport its instrument suite to multiple locations to make measurements of surface composition, atmospheric conditions, and geologic processes.

Dragonfly and CAESAR, a comet sample return mission to 67P/Churyumov–Gerasimenko, were the two finalists for the New Frontiers program Mission 4, and on 27 June 2019, NASA selected Dragonfly for development; it will launch in June 2027.

Funding

The CAESAR and Dragonfly missions received US$4 million funding each through the end of 2018 to further develop and mature their concepts. NASA announced the selection of Dragonfly on 27 June 2019, which will be built and launched by June 2027. Dragonfly will be the fourth in NASA's New Frontiers portfolio, a series of principal investigator-led planetary science investigations that fall under a development cost cap of approximately US$850 million, and including launch services, the total cost will be approximately US$1 billion.

Science objectives

Titan is similar to the very early Earth, and can provide clues to how life may have arisen on Earth. In 2005, the European Space Agency's Huygens lander acquired some atmospheric and surface measurements on Titan, detecting tholins, which are a mix of various types of hydrocarbons (organic compounds) in the atmosphere and on the surface. Because Titan's atmosphere obscures the surface at many wavelengths, the specific compositions of solid hydrocarbon materials on Titan's surface remain essentially unknown. Measuring the compositions of materials in different geologic settings will reveal how far prebiotic chemistry has progressed in environments that provide known key ingredients for life, such as pyrimidines (bases used to encode information in DNA) and amino acids, the building blocks of proteins.

Areas of particular interest are sites where extraterrestrial liquid water in impact melt or potential cryovolcanic flows may have interacted with the abundant organic compounds. Dragonfly will provide the capability to explore diverse locations to characterize the habitability of Titan's environment, investigate how far prebiotic chemistry has progressed, and search for biosignatures indicative of life based on water as solvent and even hypothetical types of biochemistry.

The atmosphere contains plentiful nitrogen and methane, and strong evidence indicates that liquid methane exists on the surface. Evidence also indicates the presence of liquid water and ammonia under the surface, which may be delivered to the surface by cryovolcanic activity.

Design and construction

Dragonfly will be a rotorcraft lander, much like a large quadcopter with double rotors, an octocopter. Redundant rotor configuration will enable the mission to tolerate the loss of at least one rotor or motor. Each of the craft's eight rotors will be about 1 m (3.3 ft) in diameter. The aircraft will travel at about 10 m/s (36 km/h; 22 mph) and climb to an altitude of up to 4 km (13,000 ft).

Flight on Titan is aerodynamically benign as Titan has low gravity and little wind, and its dense atmosphere allows for efficient rotor propulsion. The radioisotope thermoelectric generator (RTG) power source has been proven in multiple spacecraft, and the extensive use of quad drones on Earth provides a well-understood flight system that is being complemented with algorithms to enable independent actions in real-time. The craft will be designed to operate in a space radiation environment and in temperatures averaging 94 K (−179.2 °C).

Titan's dense atmosphere and low gravity mean that the flight power for a given mass is a factor of about 40 times lower than on Earth. The atmosphere has 1.45 times the pressure and about four times the density of Earth's, and local gravity (13.8% of Earth's) will make it easier to fly, although cold temperatures, lower light levels and higher atmospheric drag on the airframe will be challenges.

Dragonfly will be able to fly several kilometers, powered by a lithium-ion battery, which will be recharged by a Multi-Mission Radioisotope Thermoelectric Generator (MMRTG) during the night. MMRTGs convert the heat from the natural decay of a radioisotope into electricity. The rotorcraft will be able to travel ten kilometers on every battery charge and stay aloft for a half hour each time. The vehicle will use sensors to scout new science targets, and then return to the original site until new landing destinations are approved by mission controllers.

The Dragonfly rotorcraft will be approximately 450 kg (990 lb), and packaged inside a 3.7 m (12 ft) diameter heatshield. Regolith samples will be obtained by two sample acquisition drills and hoses, one on each landing skid, for delivery to the mass spectrometer instrument.

The craft will remain on the ground during the Titan nights, which last about 8 Earth days or 192 hours. Activities during the night may include sample collection and analysis, seismological studies like diagnosing wave activity on the northern hydrocarbon seas, meteorological monitoring, and local microscopic imaging using LED illuminators as flown on Phoenix lander and Curiosity rover. The craft will communicate directly to Earth with a high-gain antenna.

The Penn State Vertical Lift Research Center of Excellence is responsible for rotor design and analysis, rotorcraft flight-control development, scaled rotorcraft testbed development, ground testing support, and flight performance assessment.

Scientific payload

- DraMS (Dragonfly Mass Spectrometer) is a mass spectrometer to identify chemical components, especially those relevant to biological processes, in surface and atmospheric samples.

- DraGNS (Dragonfly Gamma-Ray and Neutron Spectrometer), consists of a deuterium-tritium Pulsed Neutron Generator and a set of a gamma-ray spectrometer and neutron spectrometer to identify the surface composition under the lander.

- DraGMet (Dragonfly Geophysics and Meteorology Package) is a suite of meteorological sensors including a seismometer.

- DragonCam (Dragonfly Camera Suite) is a set of microscopic and panoramic cameras to image Titan's terrain and scout for scientifically interesting landing sites.

- In addition, Dragonfly will use multiple engineering and monitoring instruments to determine characteristics of Titan's interior and atmosphere.

Trajectory

Dragonfly is expected to launch in June 2027, and will take seven years to reach Titan, arriving by 2034. The spacecraft will perform a gravitational assist flyby of Venus, and three passes by Earth to gain additional velocity. The spacecraft will be the first dedicated outer solar system mission to not visit Jupiter as it will not be within the flight path at the time of launch.

Entry and descent

The cruise stage will separate from the entry capsule ten minutes before encountering Titan's atmosphere. The lander will descend to the surface of Titan using an aeroshell and a series of two parachutes, while the spent cruise stage will burn up in uncontrolled atmospheric entry. The duration of the descent phase is expected to be 105 minutes. The aeroshell is derived from the Genesis sample return capsule, and the PICA heat shield is similar to MSL and Mars 2020 design and will protect the spacecraft for the first 6 minutes of its descent.

At a speed of Mach 1.5, a drogue parachute will deploy, to slow the capsule to subsonic speeds. Due to Titan's comparably thick atmosphere and low gravity, the drogue chute phase will last for 80 minutes. A larger main parachute will replace the drogue chute when the descent speed is sufficiently low. During the 20 minutes on the main chute, the lander will be prepared for separation. The heat shield will be jettisoned, the landing skids will be extended, and sensors such as radar and lidar will be activated. At an altitude of 1.2 km (0.75 mi), the lander will be released from its parachute, for a powered flight to the surface. The specific landing site and flight operation will be performed autonomously. This is required since the high gain antenna will not be deployed during descent, and because communication between Earth and Titan takes 70–90 minutes, each way.

Landing site

The Dragonfly rotorcraft will land initially in dunes to the southeast of the Selk impact structure at the edge of the dark region called Shangri-La. It will explore this region in a series of flights of up to 8 km (5.0 mi) each, and acquire samples from compelling areas with a diverse geography. After landing it will travel to the Selk impact crater, where in addition to tholin organic compounds, there is evidence of past liquid water.

The Selk crater is a geologically young impact crater 90 km (56 mi) in diameter, located about 800 km (500 mi) north-northwest of the Huygens lander. (7.0°N 199.0°W) Infrared measurements and other spectra by the Cassini orbiter show that the adjacent terrain exhibits a brightness suggestive of differences in thermal structure or composition, possibly caused by cryovolcanism generated by the impact — a fluidized ejecta blanket and fluid flows, now water ice. Such a region featuring a mix of organic compounds and water ice is a compelling target to assess how far the prebiotic chemistry may have progressed at the surface.