Since the 17th century and during the Age of Enlightenment (especially in 18th-century England, France, and North America), various Western philosophers and theologians formulated a critical rejection of the several religious texts belonging to the many organized religions, and began to appeal only to truths that they felt could be established by reason as the exclusive source of divine knowledge. Such philosophers and theologians were called "Deists", and the philosophical/theological position they advocated is called "Deism". Deism as a distinct philosophical and intellectual movement declined toward the end of the 18th century but had its own revival in the early 19th century. Some of its tenets continued as part of other intellectual and spiritual movements, like Unitarianism, and Deism continues to have advocates today, including with modern variants such as Christian deism and pandeism.

Enlightenment Deism

Origins

Deistical thinking has existed since ancient times, but it did not develop as a movement until after the scientific revolution, which began in the mid-sixteenth century. Deism's origins can be traced to the philosophy of ancient Greece.

Origin of the word deism

The words deism and theism are both derived from words meaning "god": Latin deus and Greek theos (θεός). The word déiste first appears in French in 1564 in a work by a Swiss Calvinist named Pierre Viret, but Deism was generally unknown in France until the 1690s when Pierre Bayle published his famous Dictionnaire Historique et Critique, which contained an article on Viret.

In English, the words deist and theist were originally synonymous, but by the 17th century the terms started to diverge in meaning. The term deist with its current meaning first appears in English in Robert Burton's The Anatomy of Melancholy (1621).

Herbert of Cherbury and early English Deism

The first major statement of Deism in English is Lord Herbert of Cherbury's book De Veritate (1624). Lord Herbert, like his contemporary Descartes, searched for the foundations of knowledge. The first two-thirds of his book De Veritate (On Truth, as It Is Distinguished from Revelation, the Probable, the Possible, and the False) are devoted to an exposition of Herbert's theory of knowledge. Herbert distinguished truths from experience and reasoning about experience from innate and revealed truths. Innate truths are imprinted on our minds, as evidenced by their universal acceptance. Herbert referred to universally accepted truths as notitiae communes—Common Notions. Herbert believed there were five Common Notions that unify all religious beliefs.

- There is one Supreme God.

- God ought to be worshipped.

- Virtue and piety are the main parts of divine worship.

- We ought to be remorseful for our sins and repent.

- Divine goodness dispenses rewards and punishments, both in this life and after it.

Herbert himself had relatively few followers, and it was not until the 1680s that Herbert found a true successor in Charles Blount (1654 – 1693).

The peak of Deism, 1696 – 1801

The appearance of John Locke's Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1690) marks an important turning-point and new phase in the history of English Deism. Lord Herbert's epistemology was based on the idea of "common notions" (or innate ideas). Locke's Essay was an attack on the foundation of innate ideas. After Locke, deists could no longer appeal to innate ideas as Herbert had done. Instead, deists were forced to turn to arguments based on experience and nature. Under the influence of Newton, they turned to the argument from design as the principal argument for the existence of God.

Peter Gay identifies John Toland's Christianity Not Mysterious (1696), and the "vehement response" it provoked, as the beginning of post-Lockian Deism. Among the notable figures, Gay describes Toland and Matthew Tindal as the best known; however, Gay considered them to be talented publicists rather than philosophers or scholars. He regards Conyers Middleton and Anthony Collins as contributing more to the substance of debate, in contrast with fringe writers such as Thomas Chubb and Thomas Woolston.

Other English Deists prominent during the period include William Wollaston, Charles Blount, Henry St John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke, and, in the latter part, Peter Annet, Thomas Chubb, and Thomas Morgan. Anthony Ashley-Cooper, 3rd Earl of Shaftesbury was also influential; though not presenting himself as a Deist, he shared many of the deists' key attitudes and is now usually regarded as a Deist.

Especially noteworthy is Matthew Tindal's Christianity as Old as the Creation (1730), which became, very soon after its publication, the focal center of the Deist controversy. Because almost every argument, quotation, and issue raised for decades can be found here, the work is often termed "the Deist's Bible". Following Locke's successful attack on innate ideas, Tindal's "Bible" redefined the foundation of Deist epistemology as knowledge based on experience or human reason. This effectively widened the gap between traditional Christians and what he called "Christian Deists", since this new foundation required that "revealed" truth be validated through human reason.

Aspects of Deism in Enlightenment philosophy

Enlightenment Deism consisted of two philosophical assertions: (1) reason, along with features of the natural world, is a valid source of religious knowledge, and (2) revelation is not a valid source of religious knowledge. Different Deist philosophers expanded on these two assertions to create what Leslie Stephen later termed the "constructive" and "critical" aspects of Deism. "Constructive" assertions—assertions that deist writers felt were justified by appeals to reason and features of the natural world (or perhaps were intuitively obvious or common notions)—included:

- God exists and created the universe.

- God gave humans the ability to reason.

"Critical" assertions—assertions that followed from the denial of revelation as a valid source of religious knowledge—were much more numerous, and included:

- Rejection of all books (including the Bible) that claimed to contain divine revelation.

- Rejection of the incomprehensible notion of the Trinity and other religious "mysteries".

- Rejection of reports of miracles, prophecies, etc.

The origins of religion

A central premise of Deism was that the religions of their day were corruptions of an original religion that was pure, natural, simple, and rational. Humanity lost this original religion when it was subsequently corrupted by priests who manipulated it for personal gain and for the class interests of the priesthood, and encrusted it with superstitions and "mysteries"—irrational theological doctrines. Deists referred to this manipulation of religious doctrine as "priestcraft", a derogatory term. For deists, this corruption of natural religion was designed to keep laypeople baffled by "mysteries" and dependent on the priesthood for information about the requirements for salvation. This gave the priesthood a great deal of power, which the Deists believed the priesthood worked to maintain and increase. Deists saw it as their mission to strip away "priestcraft" and "mysteries". Tindal, perhaps the most prominent deist writer, claimed that this was the proper, original role of the Christian Church.

One implication of this premise was that current-day primitive societies, or societies that existed in the distant past, should have religious beliefs less infused with superstitions and closer to those of natural theology. This position became less and less plausible as thinkers such as David Hume began studying the natural history of religion and suggested that the origins of religion was not in reason but in emotions, such as the fear of the unknown.

Immortality of the soul

Different Deists had different beliefs about the immortality of the soul, about the existence of Hell and damnation to punish the wicked, and the existence of Heaven to reward the virtuous. Anthony Collins, Bolingbroke, Thomas Chubb, and Peter Annet were materialists and either denied or doubted the immortality of the soul. Benjamin Franklin believed in reincarnation or resurrection. Lord Herbert of Cherbury and William Wollaston held that souls exist, survive death, and in the afterlife are rewarded or punished by God for their behavior in life. Thomas Paine believed in the "probability" of the immortality of the soul.

Miracles and divine providence

The most natural position for Deists was to reject all forms of supernaturalism, including the miracle stories in the Bible. The problem was that the rejection of miracles also seemed to entail the rejection of divine providence (that is, God taking a hand in human affairs), something that many Deists were inclined to accept. Those who believed in a watch-maker God rejected the possibility of miracles and divine providence. They believed that God, after establishing natural laws and setting the cosmos in motion, stepped away. He didn't need to keep tinkering with his creation, and the suggestion that he did was insulting. Others, however, firmly believed in divine providence, and so, were reluctantly forced to accept at least the possibility of miracles. God was, after all, all-powerful and could do whatever he wanted including temporarily suspending his own natural laws.

Freedom and necessity

Enlightenment philosophers under the influence of Newtonian science tended to view the universe as a vast machine, created and set in motion by a creator being that continues to operate according to natural law without any divine intervention. This view naturally led to what was then called "necessitarianism" (the modern term is "determinism"): the view that everything in the universe—including human behavior—is completely, causally determined by antecedent circumstances and natural law. (See, for example, La Mettrie's L'Homme machine.) As a consequence, debates about freedom versus "necessity" were a regular feature of Enlightenment religious and philosophical discussions. Reflecting the intellectual climate of the time, there were differences among Deists about freedom and determinism. Some, such as Anthony Collins, were actually necessitarians.

David Hume

Views differ on whether David Hume was a Deist, an atheist, or something else. Like the Deists, Hume rejected revelation, and his famous essay On Miracles provided a powerful argument against belief in miracles. On the other hand, he did not believe that an appeal to Reason could provide any justification for religion. In the essay Natural History of Religion (1757), he contended that polytheism, not monotheism, was "the first and most ancient religion of mankind" and that the psychological basis of religion is not reason, but fear of the unknown. Hume's account of ignorance and fear as the motivations for primitive religious belief was a severe blow to the deist's rosy picture of prelapsarian humanity basking in priestcraft-free innocence. In Waring's words:

The clear reasonableness of natural religion disappeared before a semi-historical look at what can be known about uncivilized man— "a barbarous, necessitous animal," as Hume termed him. Natural religion, if by that term one means the actual religious beliefs and practices of uncivilized peoples, was seen to be a fabric of superstitions. Primitive man was no unspoiled philosopher, clearly seeing the truth of one God. And the history of religion was not, as the deists had implied, retrograde; the widespread phenomenon of superstition was caused less by priestly malice than by man's unreason as he confronted his experience.

Deism in the United States

The Thirteen Colonies of North America, which became the United States of America after the American Revolution in 1776, were under the rule of the British Empire, and Americans, as British subjects, were influenced by and participated in the intellectual life of the Kingdom of Great Britain. English Deism was an important influence on the thinking of Thomas Jefferson and the principles of religious freedom asserted in the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. Other Founding Fathers who were influenced to various degrees by Deism were Ethan Allen, Benjamin Franklin, Cornelius Harnett, Gouverneur Morris, Hugh Williamson, James Madison, and possibly Alexander Hamilton.

In the United States, there is a great deal of controversy over whether the Founding Fathers were Christians, Deists, or something in between. Particularly heated is the debate over the beliefs of Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and George Washington.

In his Autobiography, Franklin wrote that as a young man "Some books against Deism fell into my hands; they were said to be the substance of sermons preached at Boyle's lectures. It happened that they wrought an effect on me quite contrary to what was intended by them; for the arguments of the Deists, which were quoted to be refuted, appeared to me much stronger than the refutations; in short, I soon became a thorough Deist." Like some other Deists, Franklin believed that, "The Deity sometimes interferes by his particular Providence, and sets aside the Events which would otherwise have been produc'd in the Course of Nature, or by the Free Agency of Man," and at the Constitutional Convention stated that "the longer I live, the more convincing proofs I see of this truth—that God governs in the affairs of men."

Thomas Jefferson is perhaps the Founding Father who most clearly exhibits Deistic tendencies, although he generally referred to himself as a Unitarian rather than a Deist. His excerpts of the canonical gospels (now commonly known as the Jefferson Bible) strip all supernatural and dogmatic references from the narrative on Jesus' life. Like Franklin, Jefferson believed in God's continuing activity in human affairs.

Thomas Paine is especially noteworthy both for his contributions to the cause of the American Revolution and for his writings in defense of Deism alongside the criticism of Abrahamic religions. In The Age of Reason (1793 – 1794) and other writings, he advocated Deism, promoted reason and freethought, and argued against institutionalized religions in general and the Christian doctrine in particular. The Age of Reason was short, readable, and probably the only Deistic treatise that continues to be read and influential today.

The last contributor to American Deism was Elihu Palmer (1764 – 1806), who wrote the "Bible of American Deism," Principles of Nature, in 1801. Palmer is noteworthy for attempting to bring some organization to Deism by founding the "Deistical Society of New York" and other Deistic societies from Maine to Georgia.

Deism in France and continental Europe

France had its own tradition of religious skepticism and natural theology in the works of Montaigne, Pierre Bayle, and Montesquieu. The most famous of the French Deists was Voltaire, who was exposed to Newtonian science and English Deism during his two-year period of exile in England (1726 –1728). When he returned to France, he brought both back with him, and exposed the French reading public (i.e., the aristocracy) to them in a number of books.

French Deists also included Maximilien Robespierre and Rousseau. During the French Revolution (1789 –1799), the Deistic Cult of the Supreme Being—a direct expression of Robespierre's theological views—was established briefly (just under three months) as the new state religion of France, replacing the deposed Catholic Church and the rival atheistic Cult of Reason.

Deism in Germany is not well documented. We know from correspondence with Voltaire that Frederick the Great was a Deist. Immanuel Kant's identification with Deism is controversial.

Decline of Enlightenment Deism

Peter Gay describes Enlightenment Deism as entering slow decline as a recognizable movement in the 1730s. A number of reasons have been suggested for this decline, including:

- The increasing influence of naturalism and materialism.

- The writings of David Hume and Immanuel Kant raising questions about the ability of reason to address metaphysical questions.

- The violence of the French Revolution.

- Christian revivalist movements, such as Pietism and Methodism (which emphasized a personal relationship with God), along with the rise of anti-rationalist and counter-Enlightenment philosophies such as that of Johann Georg Hamann.

Although Deism has declined in popularity over time, scholars believe that these ideas still have a lingering influence on modern society. One of the major activities of the Deists, biblical criticism, evolved into its own highly technical discipline. Deist rejection of revealed religion evolved into, and contributed to, 19th-century liberal British theology and the rise of Unitarianism.

Contemporary Deism

Contemporary Deism attempts to integrate classical Deism with modern philosophy and the current state of scientific knowledge. This attempt has produced a wide variety of personal beliefs under the broad classification of belief of "deism."

There are a number of subcategories of modern Deism, including monodeism (the default, standard concept of deism), pandeism, panendeism, spiritual deism, process deism, Christian deism, polydeism, scientific deism, and humanistic deism. Some deists see design in nature and purpose in the universe and in their lives. Others see God and the universe in a co-creative process. Some deists view God in classical terms as observing humanity but not directly intervening in our lives, while others see God as a subtle and persuasive spirit who created the world, and then stepped back to observe.

Recent philosophical discussions of Deism

In the 1960s, theologian Charles Hartshorne scrupulously examined and rejected both deism and pandeism (as well as pantheism) in favor of a conception of God whose characteristics included "absolute perfection in some respects, relative perfection in all others" or "AR," writing that this theory "is able consistently to embrace all that is positive in either deism or pandeism," concluding that "panentheistic doctrine contains all of deism and pandeism except their arbitrary negations."

Charles Taylor, in his 2007 book A Secular Age, showed the historical role of Deism, leading to what he calls an "exclusive humanism". This humanism invokes a moral order whose ontic commitment is wholly intra-human with no reference to transcendence. One of the special achievements of such deism-based humanism is that it discloses new, anthropocentric moral sources by which human beings are motivated and empowered to accomplish acts of mutual benefit. This is the province of a buffered, disengaged self, which is the locus of dignity, freedom, and discipline, and is endowed with a sense of human capability. According to Taylor, by the early 19th century this Deism-mediated exclusive humanism developed as an alternative to Christian faith in a personal God and an order of miracles and mystery. Some critics of Deism have accused adherents of facilitating the rise of nihilism.

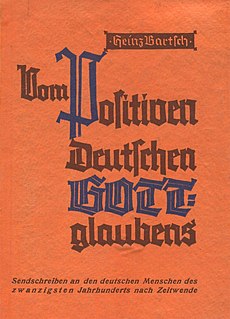

Deism in Nazi Germany

In Nazi Germany, Gottgläubig (literally: "believing in God") was a Nazi religious term for a form of non-denominationalism practised by those Germans who had officially left Christian churches but professed faith in some higher power or divine creator. Such people were called Gottgläubige ("believers in God"), and the term for the overall movement was Gottgläubigkeit ("belief in God"); the term denotes someone who still believes in a God, although without having any institutional religious affiliation. These National Socialists were not favourable towards religious institutions of their time, nor did they tolerate atheism of any type within their ranks. The 1943 Philosophical Dictionary defined gottgläubig as: "official designation for those who profess a specific kind of piety and morality, without being bound to a church denomination, whilst however also rejecting irreligion and godlessness." In the 1939 census, 3.5% of the German population identified as gottgläubig.

In the 1920 National Socialist Programme of the National Socialist German Workers' Party (NSDAP), Adolf Hitler first mentioned the phrase "Positive Christianity". The Nazi Party did not wish to tie itself to a particular Christian denomination, but with Christianity in general, and sought freedom of religion for all denominations "so long as they do not endanger its existence or oppose the moral senses of the Germanic race." (point 24). When Hitler and the NSDAP got into power in 1933, they sought to assert state control over the churches, on the one hand through the Reichskonkordat with the Roman Catholic Church, and the forced merger of the German Evangelical Church Confederation into the Protestant Reich Church on the other. This policy seems to have gone relatively well until late 1936, when a "gradual worsening of relations" between the Nazi Party and the churches saw the rise of Kirchenaustritt ("leaving the church"). Although there was no top-down official directive to revoke church membership, some Nazi Party members started doing so voluntarily and put other members under pressure to follow their example. Those who left the churches were designated as Gottgläubige ("believers in God"), a term officially recognised by the Interior Minister Wilhelm Frick on 26 November 1936. He stressed that the term signified political disassociation from the churches, not an act of religious apostasy. The term "dissident", which some church leavers had used up until then, was associated with being "without belief" (glaubenslos), whilst most of them emphasized that they still believed in a God, and thus required a different word.

The Nazi Party ideologue Alfred Rosenberg was the first to leave his church on 15 November 1933, but for the next three years he would be the only prominent Nazi leader to do so. In early 1936, SS leaders Heinrich Himmler and Reinhard Heydrich terminated their membership of the Roman Catholic Church, followed by a number of Gauleiter including Martin Mutschmann (Saxony), Carl Röver (Weser-Ems), and Robert Heinrich Wagner (Baden). In late 1936, especially Roman Catholic party members left the church, followed in 1937 by a flood of primarily Protestant party members. Hitler himself never repudiated his membership of the Roman Catholic Church; in 1941, he told his General Gerhard Engel: "I am now as before a Catholic and will always be so." However, the shifting actual religious views of Adolf Hitler remain unclear due to conflicting accounts from Hitler's associates such as Otto Strasser, Martin Bormann, Joseph Goebbels, and others.

Deism in Turkey

An early April 2018 report of the Turkish Ministry of Education, titled The Youth is Sliding towards Deism, observed that an increasing number of pupils in İmam Hatip schools was repudiating Islam in favour of Deism (irreligious belief in a creator God). The report's publication generated large-scale controversy in the Turkish press and society at large, as well as amongst conservative Islamic sects, Muslim clerics, and Islamist parties in Turkey. The progressive Muslim theologian Mustafa Öztürk noted the Deistic trend among Turkish people a year earlier, arguing that the "very archaic, dogmatic notion of religion" held by the majority of those claiming to represent Islam was causing "the new generations [to get] indifferent, even distant, to the Islamic worldview." Despite lacking reliable statistical data, numerous anecdotes and independent surveys appear to point in this direction. Although some commentators claim that the secularization of Turkey is merely a result of Western influence or even a "conspiracy," other commentators, even some pro-government ones, have come to the conclusion that "the real reason for the loss of faith in Islam is not the West but Turkey itself."

Deism in the United States

The 2001 American Religious Identification Survey (ARIS) report estimated that between 1990 and 2001 the number of self-identifying Deists grew from 6,000 to 49,000, representing about 0.02% of the U.S. population at the time. The 2008 ARIS survey found, based on their stated beliefs rather than their religious identification, that 70% of Americans believe in a personal God: roughly 12% are atheists or agnostics, and 12% believe in "a deist or paganistic concept of the Divine as a higher power" rather than a personal God.

The term "ceremonial deism" was coined in 1962 and has been used since 1984 by the Supreme Court of the United States to assess exemptions from the Establishment Clause of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, thought to be expressions of cultural tradition and not earnest invocations of a deity. It has been noted that the term does not describe any school of thought within Deism itself.