Adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) encompass various forms of physical and emotional abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction experienced in childhood. The harms of ACEs can be long-lasting, affecting people even in their adulthood. ACEs have been linked to premature death as well as to various health conditions, including those of mental disorders. Toxic stress linked to child abuse is related to a number of neurological changes in the structure of the brain and its function.

Definition and types

The concept of adverse childhood experiences refers to various traumatic events or circumstances affecting children before the age of 18 and causing mental or physical harm. There are 10 types of ACEs:

- physical abuse

- sexual abuse

- psychological abuse

- physical neglect

- psychological neglect

- witnessing domestic abuse

- having a close family member who misused drugs or alcohol

- having a close family member with mental health problems

- having a close family member who served time in prison

- parental separation or divorce on account of relationship breakdown.

The different adverse childhood experiences are not isolated and in many cases multiple ACEs impact someone at the same time.

Prevalence

Adverse childhood experiences are common across all parts of societies. A study in the USA based on a large sample of people showed that more than half of the people have had at least one ACE and 20% experienced three or more ACEs. In England around half of the population have experienced one or more ACEs.

Inequalities in society impact the chances of experiencing ACEs. People with lower socioeconomic status and those growing up in disadvantaged areas or in poverty are more likely have adverse childhood experiences and they are also more likely to have more than one.

Health outcomes due to ACEs

Childhood

With one in four children experiencing or witnessing a potentially traumatic event, the relationship between ACEs and poor health outcomes has been established for years. With multiple adverse childhood experiences being equal to various stresses, and adversity. Children who grow up in an unsafe environment are at risk for developing adverse health outcomes, affecting brain development, immune systems, and regulatory systems. Adverse childhood experiences can alter the structural development of neural networks and the biochemistry of neuroendocrine systems and may have long-term effects on the body, including speeding up the processes of disease and aging and compromising immune systems. Further research on ACEs determined that children who experience ACEs are more likely than their similar-aged peers to experience challenges in their biological, emotional, social, and cognitive functioning. Also, children who have experienced an ACE are at higher risk of being re-traumatized or suffering multiple ACEs. The amount and types of ACEs can cause significant negative impacts and increase the risk of internalizing and externalizing in children. Additionally behavioral challenges can arise in children who have been exposed to ACEs including juvenile recidivism, reduced resiliency, and lower academic performance.

Adulthood

Adults with ACE exposure report having worse mental and physical health, more serious symptoms related to illnesses, and poorer life outcomes. Across numerous studies these effects go beyond behavioral and medical issues, and include damage to DNA, higher levels of stress hormones, and reduced immune function. The effects of ACEs goes beyond just physical and behavioral health with studies reporting that people with high ACEs scores showed less trust in government COVID-19 information and polices.

It is thought that all adult depression results from something happening in childhood. That could be things like aversive childhood experiences that lead to depression, or if something that happens in adulthood that leads to depression tends to stem from something that happened in childhood as well. It seems that the main things that led children to have adult depression is that of their parent's mental health issues and childhood neglect.

Biological changes

Due to many of the early life stressors caused by exposure to ACEs there are noted changes the body in people with ACE exposures compared to people with little to no ACE exposure. This is most evident in structural changes in the brain with the hippocampus, the amygdala, and the corpus callosum being important targets of study. These areas of the brain are more vulnerable than others due to the higher density of glucocorticoid receptors in these regions of the brain. Multiple effects have been noted including diminished thickness, reduced size, and reduced size of connective networks in the brain.

Physical health

ACEs have been linked to numerous negative health and lifestyle issues into adulthood across multiple countries and regions including the United States, the European Union, South Africa, and Asia. Across all these groups researchers have reported seeing the adoption of higher rates of unhealthy lifestyle behavior including sexual risk taking, smoking, heavy drinking, and obesity. The associations between these lifestyle issues and ACEs shows a dose response relationship with people having four or more ACEs have significantly more of these lifestyle problems. Physical health problems arise in people with ACEs with a similar dose response relationship. Chronic illnesses such as asthma, arthritis, cardiovascular disease, cancer, diabetes, stroke, and migraines show increased symptom severity in step was exposure to ACEs.

Mental health

Mental health issues have been well known in the face of childhood trauma and exposure to ACEs is no different. According to a large study conducted in 21 countries nearly one in three mental health conditions in adulthood are directly related to an adverse childhood experience.

Multiple mental health conditions found to have a dose response relationship with symptom severity and prevalence including depression, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder, anxiety suicidality, bipolar disorder and schizophrenia. Depressive symptoms in adulthood showed one of the strongest dose response relationships with ACEs, with an ACE score of one increasing the risk of depressive symptoms by 50% and an ACE score of four or more showing a fourfold increase. Later research also demonstrated that ACE scores are related to increased rates and severity of psychiatric and mental disorders, as well as higher rates of prescription psychotropic medication use.

Special populations

Additionally, epigenetic transmission may occur due to stress during pregnancy or during interactions between mother and newborns. Maternal stress, depression, and exposure to partner violence have all been shown to have epigenetic effects on infants.

Implementing practices

Globally knowledge about the prevalence and consequences of adverse childhood experiences has shifted policy makers and mental health practitioners towards increasing, trauma-informed and resilience-building practices. This work has been over 20 years in the making bringing together research are implemented in communities, education settings, public health departments, social services, faith-based organizations and criminal justice.

Communities

As knowledge about the prevalence and consequences of ACEs increases, more communities seek to integrate trauma-informed and resilience-building practices into their agencies and systems.

Indigenous populations show similar patterns of mental and physical health challenges as other minority groups. Interventions have been developed in American Indian tribal communities and have demonstrated that social support and cultural involvement can ameliorate the negative physical health effects of ACEs.

There is a paucity of empirical research documenting the experiences of communities who have attempted to implement information about ACEs and trauma-informed practice into widespread public action. A study on Pottstown, Pennsylvania's process demonstrated the challenges associated with community implementation. The Pottstown Trauma-Informed Community Connection (PTICC) initiative evolved from a series of prior collectives that all had similar goals of creating community resilience in order to prevent and treat ACEs. Over the course of the two-year study, over 230 individuals from nearly 100 organizations attended one training offered by the PTICC, raising the number of engaged public sectors from 2 to 14. Participation in training and events was fairly steady and this was largely due to community networking.

However, the PTICC faced several challenges similar to those predicted by the Building Community Resilience model. These barriers included availability of resources over time, competition for power within the group, and the lack of systemic change needed to support long-term goals. Still, Pottstown has built a trauma-informed community foundation and offers lessons to other communities who have similar goals: start with a dedicated small team, identify community connectors, secure long-term financial backing, and conduct data-informed evaluations throughout.

Other community examples exist, such as Tarpon Springs, Florida which became the first trauma-informed community in 2011. Trauma-informed initiatives in Tarpon Springs include trauma-awareness training for the local housing authority, changes in programs for ex-offenders, and new approaches to educating students with learning difficulties.

Education

ACEs exposure is widespread globally, one study from the National Survey of Children's Health in the United States reported that approximately 68% of children 0–17 years old had experienced one or more ACEs. The impact of ACEs on children can manifest in difficulties focusing, self regulating, trusting others, and can lead to negative cognitive effects. One study found that a child with 4 or more ACEs was 32 times more likely to be labeled with a behavioral or cognitive problem than a child with no ACEs. Another study found that students with at least three ACEs are three times as likely to experience academic failure, six times as likely to have behavioral problems, and five times as likely to have attendance problems. The trauma-informed school movement aims to train teachers and staff to help children self-regulate, and to help families that are having problems that result in children's normal response to trauma. It also seeks to provide behavioral consequences that will not re-traumatize a child.

Trauma-informed education refers to the specific use of knowledge about trauma and its expression to modify support for children to improve their developmental success. The National Child Traumatic Stress Network (NCTSN) describes a trauma-informed school system as a place where school community members work to provide trauma awareness, knowledge and skills to respond to potentially negative outcomes following traumatic stress. The NCTSN published a study that discussed the Attachment, Self-Regulation, and Competency (ARC) model, which other researchers have based their subsequent studies of trauma-informed education practices off of. Trauma-sensitive or trauma-informed schooling has become increasingly popular in Washington, Massachusetts, and California in the last 10 years.

Literacy

ACEs in childhood and adolescence can affect literacy development in many ways. Children who have faced trauma encounter more learning challenges in school and higher levels of stress internally. Building literacy skills can be negatively impacted both by the lack of literacy experiences in the home, missing parts of early-childhood education, and by actually altering brain development. There are techniques that can be employed by educators and clinicians to try and remediate the effects of the adverse experiences and move children forward in their literacy and educational development.

ACEs affect parts of the brain that involve memory, executive functioning, and attention. The parts of the brain and hormones that register fear and stress are in overdrive, whereas the prefrontal cortex, which regulates executive functions, is compromised. This impacts impulse control, focus, and critical thinking. Memory is also a struggle as there is less capacity to process new input. The stress of ACEs creates a state of "fight, flight, or freeze" which leaves children unavailable for learning. The ability to process new information or collaborate with peers in school is eclipsed by the brain's necessity to survive the stress experienced in their environment outside of school. The inconsistency and instability of the home environment alters the many cognitive processes necessary for effective literacy acquisition.

Young people who are refugees experience trauma whether they were part of the immigration process or were born in the country (where they currently attend school) where the family settled. During this resettlement phase many of the second-generation refugee child's problems come to light. The disruption in education and instability in the home, as a result of the family's journey, can lead to gaps in exposures to literacy in the home. Literacy experiences outside of school include parents reading with kids and borrowing or buying books for the home. Early-childhood literacy education includes explicit teaching of reading and writing skills, building phonological awareness, and academic vocabulary. Resettlement affects children's phonemic awareness and exposure to academic vocabulary since many families are unable to fully provide these out of school experiences. If the child was non-English speaking, then they are acquiring English as a new language. There already exists an achievement gap between native-English speakers in the United States and students who are learning English as their second (or third or fourth) language.

The resulting literacy issues from trauma, reflected in low reading scores, puts children with ACEs at-risk for grade retention. As students, they are almost twice as likely to leave high school without graduating. While there are many years from when a young child starts Kindergarten and an adolescent enters high school, there is a link between weak emergent literacy leading to eventually dropping out of high school. It is crucial to intervene as early as possible.

Trauma- informed educators and clinicians can help remediate both young children and adolescents in school. With a knowledge and sensitivity of ACEs and their effects, proper and effective interventions can be implemented. This can also begin to create a stable environment in which children can learn and create stable attachments. Physical movement in the form of "brain energizers" can help regulate children's brains and alleviate stress when done 1-2 times during the school day. In one study, both behavior and literacy skills were assessed to see how effective the physical movement, or "brain energizers" were. Literacy scores for a classroom that used the brain energizers (which ranged from movement activities found online to other movement activities selected by the teacher and students), improved by 117% from beginning to end of year. In a school setting, the person who has experienced trauma and the person who is in the moment with the person trying to talk or write about it can connect, even when language fails to adequately describe the depth and complexity of the emotions felt. While there is an inherent discomfort in this, educators can embrace this discomfort and give children a space to express this, as best they can, in the classroom. Those who are able to develop more "resilience" might be able to function better in school, but this is dependent on the ratio of protective factors compared to ACEs.

Social services

Social service providers—including welfare systems, housing authorities, homeless shelters, and domestic violence centers – are adopting trauma-informed approaches that help to prevent ACEs or minimize their impact. Utilizing tools that screen for trauma can help a social service worker direct their clients to interventions that meet their specific needs. Trauma-informed practices can also help social service providers look at how trauma impacts the whole family.

Trauma-informed approaches can improve child welfare services by openly discussing trauma and addressing parental trauma. The New Hampshire Division for Children Youth and Families (DCYF) is taking a trauma-informed approach to their foster care services by educating staff about childhood trauma, screening children entering foster care for trauma, using trauma-informed language to mitigate further traumatization, mentoring birth parents and involving them in collaborative parenting, and training foster parents to be trauma-informed.

Housing authorities are also becoming trauma-informed. Supportive housing can sometimes recreate control and power dynamics associated with clients' early trauma. This can be reduced through trauma-informed practices, such as training staff to be respectful of clients' space by scheduling appointments and not letting themselves into clients' private spaces, and also understanding that an aggressive response may be trauma-related coping strategies. Up to 50% of people with housing insecurity experienced at least four ACEs.

A study in the UK looked at the views of young people exposed to ACEs on what support they needed from social services. The study grouped the findings into three categories: emotional support, practical support and service delivery. Emotional support included interacting with other young people for support and a sense solidarity, and supportive relationships with adults that are based on empathy, active listening and non-judgement. Practical support meant information about the available services, practical advice about everyday challenges and respite from these challenges through recreation. Young people expected service delivery to be continuous and dependable, and they needed flexibility and control over the support processes. The needs of young people with ACEs were found not to match the types of support they are offered.

Health care services

Screening for or talking about ACEs with parents and children can help to foster healthy physical and psychological development and can help doctors understand the circumstances that children and their parents are facing. By screening for ACEs in children, pediatric doctors and nurses can better understand behavioral problems. Some doctors have questioned whether some behaviors resulting in attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) diagnoses are in fact reactions to trauma. Children who have experienced four or more ACEs are three times as likely to take ADHD medication when compared with children with less than four ACEs. Screening parents for their ACEs allows doctors to provide the appropriate support to parents who have experienced trauma, helping them to build resilience, foster attachment with their children, and prevent a family cycle of ACEs.

For people whose adverse childhood experiences were of abuse or neglect cognitive behavioural therapy has been studied and shown to be effective.

Public health

Objections to screening for ACEs include the lack of randomized controlled trials that show that such measures can be used to actually improve health outcomes, the scale collapses items and has limited item coverage, there are no standard protocols for how to use the information gathered, and that revisiting negative childhood experiences could be emotionally traumatic. Other obstacles to adoption include that the technique is not taught in medical schools, is not billable, and the nature of the conversation makes some doctors personally uncomfortable. Some public health centers see ACEs as an important way (especially for mothers and children) to target health interventions for individuals during sensitive periods of development.

Resilience and resources

Resilience is the ability to adapt or cope in the face of significant adversity and threats such as health problems, stress experienced in the workplace or home. Resiliency can moderate the relationship of the effects of ACEs and health problem in adulthood. Being able use emotion regulation resources such as cognitive reappraisal and mindfulness people are able to protect themselves from the potential negative effects of stressors. These skills can be taught to people but people living with ACEs score lower on measures of resilience and emotion regulation.

Resilience and access to other resources are protective factors against the effects of exposure to ACEs. Increasing resilience in children can help provide a buffer for those who have been exposed to trauma and have a higher ACE score. People and children who have fostered resiliency have the skills and abilities to embrace behaviors that can foster growth. In childhood, resiliency and attachment security can be fostered from having a caring adult in a child's life.

Adverse childhood experiences study

The Adverse Childhood Experiences Study (ACE Study) is a research study conducted by the U.S. health maintenance organization Kaiser Permanente and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention that was originally published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine. Participants were recruited to the study between 1995 and 1997 and have since been in long-term follow up for health outcomes. The study has demonstrated an association of adverse childhood experiences (ACEs) with health and social problems across the lifespan. The study has produced many scientific articles and conference and workshop presentations that examine ACEs.

In the 1980s, the dropout rate of participants at Kaiser Permanente's obesity clinic in San Diego, California, was about 50%; despite all of the dropouts successfully losing weight under the program. Vincent Felitti, head of Kaiser Permanente's Department of Preventive Medicine in San Diego, conducted interviews with people who had left the program, and discovered that a majority of 286 people he interviewed had experienced childhood sexual abuse. The interview findings suggested to Felitti that weight gain might be a coping mechanism for depression, anxiety, and fear.

Felitti and Robert Anda from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) went on to survey childhood trauma experiences of over 17,000 Kaiser Permanente patient volunteers. The 17,337 participants were volunteers from approximately 26,000 consecutive Kaiser Permanente members. About half were female; 74.8% were white; the average age was 57; 75.2% had attended college; all had jobs and good health care, because they were members of the Kaiser health maintenance organization. Participants were asked about different types of adverse childhood experiences that had been identified in earlier research literature: Physical abuse, Sexual abuse, Emotional abuse, Physical neglect, Emotional neglect, Exposure to domestic violence, Household substance abuse, Household mental illness, Parental separation or divorce, Incarcerated household member.

Findings

According to the United States' Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, the ACE study found that:

- Adverse childhood experiences are common. For example, 28% of study participants reported physical abuse and 21% reported sexual abuse. Many also reported experiencing a divorce or parental separation, or having a parent with a mental and/or substance use disorder.

- Adverse childhood experiences often occur together. Almost 40% of the original sample reported two or more ACEs and 12.5% experienced four or more. Because ACEs occur in clusters, many subsequent studies have examined the cumulative effects of ACEs rather than the individual effects of each.

- Adverse childhood experiences have a dose–response relationship with many health problems. As researchers followed participants over time, they discovered that a person's cumulative ACEs score has a strong, graded relationship to numerous health, social, and behavioral problems throughout their lifespan, including substance use disorders. Furthermore, many problems related to ACEs tend to be comorbid, or co-occurring.

About two-thirds of individuals reported at least one adverse childhood experience; 87% of individuals who reported one ACE reported at least one additional ACE. The number of ACEs was strongly associated with adulthood high-risk health behaviors such as smoking, alcohol and drug abuse, promiscuity, and severe obesity, and correlated with ill-health including depression, heart disease, cancer, chronic lung disease and shortened lifespan. Compared to an ACE score of zero, having four adverse childhood experiences was associated with a seven-fold (700%) increase in alcoholism, a doubling of risk of being diagnosed with cancer, and a four-fold increase in emphysema; an ACE score above six was associated with a 30-fold (3000%) increase in attempted suicide.

The ACE study's results suggest that maltreatment and household dysfunction in childhood contribute to health problems decades later. These include chronic diseases—such as heart disease, cancer, stroke, and diabetes—that are the most common causes of death and disability in the United States. These findings are important because they provided a link between the effects of child maltreatment and negative effects later in life which had not been established as clearly before this study.

Subsequent surveys

The ACE Study has produced more than 50 articles that look at the prevalence and consequences of ACEs. It has been influential in several areas. Subsequent studies have confirmed the high frequency of adverse childhood experiences.

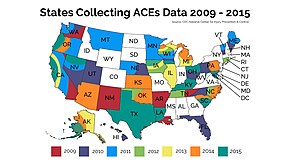

The original study questions have been used to develop a 10-item screening questionnaire. Numerous subsequent surveys have confirmed that adverse childhood experiences are frequent.

The Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System (BRFSS) which is run by the CDC, is an annual survey conducted in waves by groups of individual state and territory health departments.. An expanded ACE survey instrument was included in several states found each state. Adverse childhood experiences were even more frequent in studies in urban Philadelphia and in a survey of young mothers (mostly younger than 19). Surveys of adverse childhood experiences have been conducted in multiple EU member countries.