In medicine, a biomarker is a measurable indicator of the severity or presence of some disease state. It may be defined as a "cellular, biochemical or molecular alteration in cells, tissues or fluids that can be measured and evaluated to indicate normal biological processes, pathogenic processes, or pharmacological responses to a therapeutic intervention." More generally a biomarker is anything that can be used as an indicator of a particular disease state or some other physiological state of an organism. According to the WHO, the indicator may be chemical, physical, or biological in nature - and the measurement may be functional, physiological, biochemical, cellular, or molecular.

A biomarker can be a substance that is introduced into an organism as a means to examine organ function or other aspects of health. For example, rubidium chloride is used in isotopic labeling to evaluate perfusion of heart muscle. It can also be a substance whose detection indicates a particular disease state, for example, the presence of an antibody may indicate an infection. More specifically, a biomarker indicates a change in expression or state of a protein that correlates with the risk or progression of a disease, or with the susceptibility of the disease to a given treatment. Biomarkers can be characteristic biological properties or molecules that can be detected and measured in parts of the body like the blood or tissue. They may indicate either normal or diseased processes in the body. Biomarkers can be specific cells, molecules, or genes, gene products, enzymes, or hormones. Complex organ functions or general characteristic changes in biological structures can also serve as biomarkers. Although the term biomarker is relatively new, biomarkers have been used in pre-clinical research and clinical diagnosis for a considerable time. For example, body temperature is a well-known biomarker for fever. Blood pressure is used to determine the risk of stroke. It is also widely known that cholesterol values are a biomarker and risk indicator for coronary and vascular disease, and that C-reactive protein (CRP) is a marker for inflammation.

Biomarkers are useful in a number of ways, including measuring the progress of disease, evaluating the most effective therapeutic regimes for a particular cancer type, and establishing long-term susceptibility to cancer or its recurrence. Biomarkers characterize disease progression starting from the earliest natural history of the disease. Biomarkers assess disease susceptibility and severity, which allows one to predict outcomes, determine interventions and evaluate therapeutic responses. From a forensics and epidemiologic perspective, biomarkers offer unique insight about the relationships between environmental risk factors. The parameter can be chemical, physical or biological. In molecular terms biomarker is "the subset of markers that might be discovered using genomics, proteomics technologies or imaging technologies. Biomarkers play major roles in medicinal biology. Biomarkers help in early diagnosis, disease prevention, drug target identification, drug response etc. Several biomarkers have been identified for many diseases such as serum LDL for cholesterol, blood pressure, and P53 gene and MMPs as tumor markers for cancer.

It is necessary to distinguish between disease-related and drug-related biomarkers. Disease-related biomarkers give an indication of the probable effect of treatment on patient (risk indicator or predictive biomarkers), if a disease already exists (diagnostic biomarker), or how such a disease may develop in an individual case regardless of the type of treatment (prognostic biomarker). Predictive biomarkers help to assess the most likely response to a particular treatment type, while prognostic markers shows the progression of disease with or without treatment. In contrast, drug-related biomarkers indicate whether a drug will be effective in a specific patient and how the patient's body will process it.

In addition to long-known parameters, such as those included and objectively measured in a blood count, there are numerous novel biomarkers used in the various medical specialties. Currently, intensive work is taking place on the discovery and development of innovative and more effective biomarkers. These "new" biomarkers have become the basis for preventive medicine, meaning medicine that recognises diseases or the risk of disease early, and takes specific countermeasures to prevent the development of disease. Biomarkers are also seen as the key to personalised medicine, treatments individually tailored to specific patients for highly efficient intervention in disease processes. Often, such biomarkers indicate changes in metabolic processes.

The "classic" biomarker in medicine is a laboratory parameter that the doctor can use to help make decisions in making a diagnosis and selecting a course of treatment. For example, the detection of certain autoantibodies in patient blood is a reliable biomarker for autoimmune disease, and the detection of rheumatoid factors has been an important diagnostic marker for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) for over 50 years. For the diagnosis of this autoimmune disease the antibodies against the bodies own citrullinated proteins are of particular value. These ACPAs, (ACPA stands for Anti-citrullinated protein/peptide antibody) can be detected in the blood before the first symptoms of RA appear. They are thus highly valuable biomarkers for the early diagnosis of this autoimmune disease. In addition, they indicate if the disease threatens to be severe with serious damage to the bones and joints, which is an important tool for the doctor when providing a diagnosis and developing a treatment plan.

There are also more and more indications that ACPAs can be very useful in monitoring the success of treatment for RA. This would make possible the accurate use of modern treatments with biologicals. Physicians hope to soon be able to individually tailor rheumatoid arthritis treatments for each patient.

According to Häupl T. et al. prediction of response to treatment will become the most important aim of biomarker research in medicine. With the growing number of new biological agents, there is increasing pressure to identify molecular parameters such as ACPAs that will not only guide the therapeutic decision but also help to define the most important targets for which new biological agents should be tested in clinical studies.

An NIH study group committed to the following definition in 1998: "a characteristic that is objectively measured and evaluated as an indicator of normal biologic processes, pathogenic processes, or pharmacologic responses to a therapeutic intervention." In the past, biomarkers were primarily physiological indicators such as blood pressure or heart rate. More recently, biomarker is becoming a synonym for molecular biomarker, such as elevated prostate specific antigen as a molecular biomarker for prostate cancer, or using enzyme assays as liver function tests. There has recently been heightened interest in the relevance of biomarkers in oncology, including the role of KRAS in colorectal cancer and other EGFR-associated cancers. In patients whose tumors express the mutated KRAS gene, the KRAS protein, which forms part of the EGFR signaling pathway, is always 'turned on'. This overactive EGFR signaling means that signaling continues downstream – even when the upstream signaling is blocked by an EGFR inhibitor, such as cetuximab (Erbitux) – and results in continued cancer cell growth and proliferation. Testing a tumor for its KRAS status (wild-type vs. mutant) helps to identify those patients who will benefit most from treatment with cetuximab.

Currently, effective treatment is available for only a small percentage of cancer patients. In addition, many cancer patients are diagnosed at a stage where the cancer has advanced too far to be treated. Biomarkers have the ability to greatly enhance cancer detection and the drug development process. In addition, biomarkers will enable physicians to develop individualized treatment plans for their cancer patients; thus allowing doctors to tailor drugs specific to their patient's tumor type. By doing so, drug response rate will improve, drug toxicity will be limited and costs associated with testing various therapies and the ensuing treatment for side effects will decrease.

Biomarkers also cover the use of molecular indicators of environmental exposure in epidemiologic studies such as human papilloma virus or certain markers of tobacco exposure such as 4-(methylnitrosamino)-1-(3-pyridyl)-1-butanone (NNK). To date no biomarkers have been established for head and neck cancer.

Biomarker requirements

For chronic diseases, whose treatment may require patients to take medications for years, accurate diagnosis is particularly important, especially when strong side effects are expected from the treatment. In these cases, biomarkers are becoming more and more important, because they can confirm a difficult diagnosis or even make it possible in the first place. A number of diseases, such as Alzheimer's disease or rheumatoid arthritis, often begin with an early, symptom-free phase. In such symptom-free patients there may be more or less probability of actually developing symptoms. In these cases, biomarkers help to identify high-risk individuals reliably and in a timely manner so that they can either be treated before onset of the disease or as soon as possible thereafter.

In order to use a biomarker for diagnostics, the sample material must be as easy to obtain as possible. This may be a blood sample taken by a doctor, a urine or saliva sample, or a drop of blood like those diabetes patients extract from their own fingertips for regular blood-sugar monitoring.

For rapid initiation of treatment, the speed with which a result is obtained from the biomarker test is critical. A rapid test, which delivers a result after only a few minutes, is optimal. This makes it possible for the physician to discuss with the patient how to proceed and if necessary to start treatment immediately after the test.

Naturally, the detection method for a biomarker must be accurate and as easy to carry out as possible. The results from different laboratories may not differ significantly from each other, and the biomarker must naturally have proven its effectiveness for the diagnosis, prognosis, and risk assessment of the affected diseases in independent studies.

A biomarker for clinical use needs good sensitivity and specificity e.g. ≥0.9, and good specificity e.g. ≥0.9 although they should be chosen with the population in mind so positive predictive value and negative predictive value are more relevant.

Biomarker classification and application

Biomarkers can be classified based on different criteria.

Based on their characteristics they can be classified as imaging biomarkers (CT, PET, MRI) or molecular biomarkers with three subtypes: volatile, like breath, body fluid, or biopsy biomarkers.

Molecular biomarkers refer to non-imaging biomarkers that have biophysical properties, which allow their measurements in biological samples (e.g., plasma, serum, cerebrospinal fluid, bronchoalveolar lavage, biopsy) and include nucleic acids-based biomarkers such as gene mutations or polymorphisms and quantitative gene expression analysis, peptides, proteins, lipids metabolites, and other small molecules.

Biomarkers can also be classified based on their application such as diagnostic biomarkers (i.e., cardiac troponin for the diagnosis of myocardial infarction), staging of disease biomarkers (i.e., brain natriuretic peptide for congestive heart failure), disease prognosis biomarkers (cancer biomarkers), and biomarkers for monitoring the clinical response to an intervention (HbAlc for antidiabetic treatment). Another category of biomarkers includes those used in decision making in early drug development. For instance, pharmacodynamic (PD) biomarkers are markers of a certain pharmacological response, which are of special interest in dose optimization studies.

Classes

Three broad classes of biomarkers are prognostic biomarkers, predictive biomarkers and pharmacodynamic biomarkers.

Prognostic

Prognostic biomarkers give intervention-independent information on disease status through screening, diagnosis and disease monitoring. Prognostic biomarkers can signify individuals in the latent period of a disease's natural history, allowing optimal therapy and prevention until the disease's termination. Prognostic biomarkers give information on disease status by measuring the internal precursors that increase or decrease the likelihood of attaining a disease. For example, blood pressure and cholesterol are biomarkers for CVD. Prognostic biomarkers can be direct or indirect to the causal pathway of a disease. If a prognostic biomarker is a direct step in the causal pathway, it is one of the factors or products of the disease. A prognostic biomarker could be indirectly associated with a disease if it is related to a change caused by the exposure, or related to an unknown factor connected with the exposure or disease.

Predictive

Predictive biomarkers measure the effect of a drug and tell if the drug is having its expected activity, but do not offer any direct information on the disease. Predictive biomarkers are highly sensitive and specific; therefore they increase diagnostic validity of a drug or toxin's site-specific effect by eliminating recall bias and subjectivity from those exposed. For example, when an individual is exposed to a drug or toxin, the concentration of that drug or toxin within the body, or the biological effective dose, provides a more accurate prediction for the effect of the drug or toxin compared to an estimation or measurement of the toxin from the origin or external environment.

Pharmacodynamic

Pharmacodynamic (PD) biomarkers can measure the direct interaction between a drug and its receptor. Pharmacodynamic biomarkers reveal drug mechanisms, if the drug has its intended effect on the biology of the disease, ideal biological dosing concentrations, and physiologic response/resistance mechanisms. Pharmacodynamic biomarkers are particularly relevant in drug mechanisms of tumor cells, where pharmacodynamic endpoints for drug interventions can be assessed directly on tumor tissues. For example, protein phosphorylation biomarkers indicate alterations in target protein kinases and activation of downstream signaling molecules.

Types

Biomarkers validated by genetic and molecular biology methods can be classified into three types.

- Type 0 — Natural history markers

- Type 1 — Drug activity markers

- Type 2 — Surrogate markers

Discovery of molecular biomarkers

Molecular biomarkers have been defined as biomarkers that can be discovered using basic and acceptable platforms such as genomics and proteomics. Many genomic and proteomics techniques are available for biomarker discovery and a few techniques that are recently being used can be found on that page. Apart from genomics and proteomics platforms biomarker assay techniques, metabolomics, lipidomics, glycomics, and secretomics are the most commonly used as techniques in identification of biomarkers.

Clinical applications

Biomarkers can be classified on their clinical applications as molecular biomarkers, cellular biomarkers or imaging biomarkers.

Molecular

Four of the main types of molecular biomarkers are genomic biomarkers, transcriptomic biomarkers, proteomic biomarkers and metabolic biomarkers.

Genomic

Genomic biomarkers analyze DNA by identifying irregular sequences in the genome, typically a single nucleotide polymorphism. Genetic biomarkers are particularly significant in cancer because most cancer cell lines carry somatic mutations. Somatic mutations are distinguishable from hereditary mutations because the mutation is not in every cell; just the tumor cells, making them easy targets.

Transcriptomic

Transcriptomic biomarkers analyze all RNA molecules, not solely the exome. Transcriptomic biomarkers reveal the molecular identity and concentration of RNA in a specific cell or population. Pattern-based RNA expression analysis provides increased diagnostic and prognostic capability in predicting therapeutic responses for individuals. For example, distinct RNA subtypes in breast cancer patients have different survival rates.

Proteomic

Proteomics permits the quantitative analysis and detection of changes to proteins or protein biomarkers. Protein biomarkers detect a variety of biological changes, such as protein-protein interactions, post-translational modifications and immunological responses.

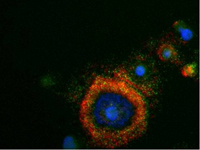

Cellular

Cellular biomarkers allow cells to be isolated, sorted, quantified and characterized by their morphology and physiology. Cellular biomarkers are used in both clinical and laboratory settings, and can discriminate between a large sample of cells based on their antigens. An example of a cellular biomarker sorting technique is Fluorescent-activated cell sorting.

Imaging biomarkers

Imaging biomarkers allow earlier detection of disease compared to molecular biomarkers, and streamline translational research in the drug discovery marketplace. For example, one could determine the percent of receptors a drug targets, shortening the time and money of research during the new drug development stage. Imaging biomarkers also are non-invasive, which is a clinical advantage over molecular biomarkers. Some of the image-based biomarkers are X-Ray, Computed Tomography (CT), Positron Emission Tomography (PET), Single Photo Emission Computed Tomography (SPECT) and Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI).

Many new biomarkers are being developed that involve imaging technology. Imaging biomarkers have many advantages. They are usually noninvasive, and they produce intuitive, multidimensional results. Yielding both qualitative and quantitative data, they are usually relatively comfortable for patients. When combined with other sources of information, they can be very useful to clinicians seeking to make a diagnosis.

Cardiac imaging is an active area of biomarker research. Coronary angiography, an invasive procedure requiring catheterization, has long been the gold standard for diagnosing arterial stenosis, but scientists and doctors hope to develop noninvasive techniques. Many believe that cardiac computed tomography (CT) has great potential in this area, but researchers are still attempting to overcome problems related to "calcium blooming," a phenomenon in which calcium deposits interfere with image resolution. Other intravascular imaging techniques involving magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), optical coherence tomography (OCT), and near infrared spectroscopy are also being investigated.

Another new imaging biomarker involves radiolabeled fludeoxyglucose. Positron emission tomography (PET) can be used to measure where in the body cells take up glucose. By tracking glucose, doctors can find sites of inflammation because macrophages there take up glucose at high levels. Tumors also take up a lot of glucose, so the imaging strategy can be used to monitor them as well. Tracking radiolabeled glucose is a promising technique because it directly measures a step known to be crucial to inflammation and tumor growth.

Imaging disease biomarkers by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI)

MRI has the advantages of having very high spatial resolution and is very adept at morphological imaging and functional imaging. MRI does have several disadvantages though. First, MRI has a sensitivity of around 10−3 mol/L to 10−5 mol/L which, compared to other types of imaging, can be very limiting. This problem stems from the fact that the difference between atoms in the high energy state and the low energy state is very small. For example, at 1.5 tesla, a typical field strength for clinical MRI, the difference between high and low energy states is approximately 9 molecules per 2 million. Improvements to increase MR sensitivity include increasing magnetic field strength, and hyperpolarization via optical pumping or dynamic nuclear polarization. There are also a variety of signal amplification schemes based on chemical exchange that increase sensitivity.

To achieve molecular imaging of disease biomarkers using MRI, targeted MRI contrast agents with high specificity and high relaxivity (sensitivity) are required. To date, many studies have been devoted to developing targeted-MRI contrast agents to achieve molecular imaging by MRI. Commonly, peptides, antibodies, or small ligands, and small protein domains, such as HER-2 affibodies, have been applied to achieve targeting. To enhance the sensitivity of the contrast agents, these targeting moieties are usually linked to high payload MRI contrast agents or MRI contrast agents with high relaxivities.

Examples

- Embryonic: Embryonic biomarkers are very important to fetuses, as each cell's role is decided through the use of biomarkers. Research has been conducted concerning the use of embryonic stem cells (ESCs) in regenerative medicine. This is because certain biomarkers within a cell could be altered (most likely in the tertiary stage of their formation) to change the future role of the cell, thereby creating new ones. One example of an embryonic biomarker is the protein Oct-4.

- Autism: ASDs are complex; autism is a medical condition with several etiologies caused due to the interactions between environmental conditions and genetic vulnerability. The challenge in finding out the biomarkers related to ASDs is that they may reflect genetic or neurobiological changes that may be active only to a certain point. ASDs show heterogeneous clinical symptoms and genetic architecture, which have hindered the identification of common genetic susceptibility factors. Still, many researches are being done to find out the main reason behind the genetic incomparability.

- Cancer: Biomarkers have an extremely high upside for therapeutic interventions in cancer patients. Most cancer biomarkers consist of proteins or altered segments of DNA, and are expressed in all cells, just at higher rates in cancer cells. There has not yet been one, universal tumor biomarker, but there is a biomarker for every type of cancer. These tumor biomarkers are used to track the health of tumors, but cannot serve as the sole diagnostic for specific cancers. Examples of tumoral markers used to follow up cancer treatment are the Carcinoembryonic Antigen (CEA) for colorectal cancer and the Prostate Specific Antigen (PSA) for prostate cancer. In 2014, Cancer research identified Circulating Tumor Cells (CTCs) and Circulating Tumor DNA (ctDNA) as metastasizing tumor biomarkers with special cellular differentiation and prognostic skills. Innovative technology needs to be harnessed to determine the full capabilities of CTCs and ctDNA, but insight into their roles has potential for new understanding of cancer evolution, invasion and metastasis.

List of Biomarkers

In alphabetic order

- Alanine transaminase (ALT)

- Body fat percentage

- Body mass index

- Body temperature

- Blood pressure

- Blood sugar level

- Complete blood count

- Creatinine

- C-reactive protein (inflammation)

- Heart rate

- Hematocrit (HCT)

- Hemoglobin (Hgb)

- Mean corpuscular volume (MCV)

- Red Blood Cell Count (RBC)

- Thyroid-stimulating hormone (TSH)

- Triglyceride

- Waist circumference

- Waist-to-hip ratio (WHR)