From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

The Trail of Tears Memorial at the

New Echota Historic Site.

The

Trail of Tears was a series of forced removals of

Native American nations from their ancestral homelands in the

Southeastern United States to an area west of the

Mississippi River

that had been designated as Native Territory. The forced relocations

were carried out by various government authorities following the passage

of the

Indian Removal Act

in 1830. The relocated people suffered from exposure, disease, and

starvation while en route, and more than four thousand died before

reaching their various destinations. The removal included members of the

Cherokee,

Muscogee,

Seminole,

Chickasaw, and

Choctaw nations. The phrase "Trail of Tears" originated from a description of the removal of the Cherokee Nation in 1838.

[1][2][3]

Between 1830 and 1850, the Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek, Seminole, and

Cherokee people (including Native Americans, and the African freedmen

and slaves who lived among them) were forcibly removed from their

traditional lands in the Southeastern United States, and relocated

farther west.

[4] Those Native Americans that were relocated were forced to march to their destinations by state and local militias.

[5]

The

Cherokee removal in 1838 (the last forced removal east of the Mississippi) was brought on by the discovery of gold near

Dahlonega, Georgia in 1828, resulting in the

Georgia Gold Rush.

[6] Approximately 2,000-6,000 of the 16,543 relocated Cherokee perished along the way.

[7][8][9][10][11]

Historical context

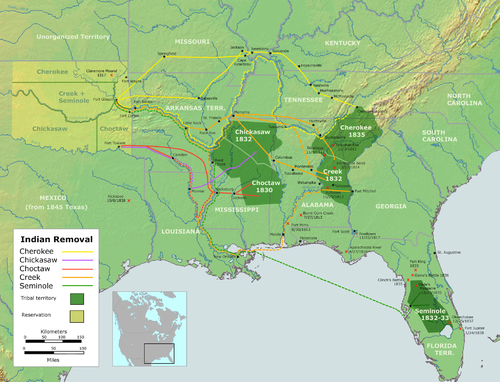

Map of United States

Indian Removal, 1830-1835. Oklahoma is depicted in light yellow-green.

In 1830, a group of Indians collectively referred to as the

Five Civilized Tribes, the Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Muscogee, and Seminole, were living as

autonomous nations in what would be later called the American

Deep South. The process of cultural transformation, as proposed by

George Washington and

Henry Knox, was gaining momentum, especially among the Cherokee and Choctaw.

[12]

American settlers had been pressuring the federal government to

remove Indians from the Southeast; many settlers were encroaching on

Indian lands, while others wanted more land made available to white

settlers. Although the effort was vehemently opposed by many, including

U.S. Congressman

Davy Crockett of Tennessee,

President Andrew Jackson was able to gain Congressional passage of the

Indian Removal Act of 1830, which authorized the government to extinguish Indian title to lands in the Southeast.

In 1831, the Choctaw became the first Nation to be removed, and their

removal served as the model for all future relocations. After two wars,

many Seminoles were removed in 1832. The Creek removal followed in

1834, the Chickasaw in 1837, and lastly the Cherokee in 1838.

[13]

Many Indians remained in their ancestral homelands; some Choctaw are

found in Mississippi, Creek in Alabama and Florida, Cherokee in

North Carolina,

and Seminole in Florida; a small group had moved to the Everglades and

were never defeated by the government of the United States. A limited

number of non-Indians, including some Africans (many as slaves, and

others as spouses), also accompanied the Indians on the trek westward.

[13]

By 1837, 46,000 Indians from the southeastern states had been removed

from their homelands, thereby opening 25 million acres (100,000 km

2) for predominantly white settlement.

[13]

Prior to 1830, the fixed boundaries of these autonomous

tribal nations, comprising large areas of the United States, were subject to continual cession and annexation, in part due to pressure from

squatters and the threat of military force in the newly declared U.S.

territories—federally administered regions whose boundaries supervened upon the Native treaty claims. As these territories became

U.S. states,

state governments sought to dissolve the boundaries of the Indian

nations within their borders, which were independent of state

jurisdiction, and to expropriate the land therein. These pressures were

exacerbated by U.S. population growth and the expansion of

slavery in the South, with the rapid development of cotton cultivation in the uplands following the invention of the cotton gin.

[14]

Jackson's role

The removals, conducted under Presidents

Andrew Jackson and

Martin Van Buren, followed the

Indian Removal Act of 1830.

The Act provided the President with powers to exchange land with Native

tribes and provide infrastructure improvements on the existing lands.

The law also gave the president power to pay for transportation costs to

the West, should tribes choose to relocate. The law did not, however,

allow the President to force tribes to move West without a mutually

agreed-upon treaty.

[15]

In the years following the Act, the Cherokee filed several lawsuits

regarding conflicts with the state of Georgia. Some of these cases

reached the Supreme Court, the most influential being

Worcester v. Georgia

(1832). Samuel Worcester and other non-Indians were convicted by

Georgia law for residing in Cherokee territory in the state of Georgia,

without a license. Worcester was sentenced to prison for four years and

appealed the ruling, arguing that this sentence violated treaties made

between Indian nations and the United States federal government by

imposing state laws on Cherokee lands. The Court ruled in Worcester's

favor, declaring that the Cherokee Nation was subject only to federal

law and that the

Supremacy Clause

barred legislative interference by the state of Georgia. Chief Justice

Marshall argued, "The Cherokee nation, then, is a distinct community

occupying its own territory in which the laws of Georgia can have no

force. The whole intercourse between the United States and this Nation,

is, by our constitution and laws, vested in the government of the United

States."

[16][17]

Andrew Jackson did not listen to the Supreme Court mandate barring

Georgia from intruding on Cherokee lands. He feared that enforcement

would lead to open warfare between federal troops and the Georgia

militia, which would compound the

ongoing crisis in South Carolina and lead to a broader civil war. Instead, he vigorously negotiated a land exchange treaty with the Cherokee.

[18] Political opponents

Henry Clay and

John Quincy Adams, who supported the

Worcester decision, were outraged by Jackson’s refusal to uphold Cherokee claims against the state of Georgia.

[19] Ralph Waldo Emerson wrote an account of Cherokee assimilation into the American culture, declaring his support of the

Worcester decision.

[20][21]

Jackson chose to continue with Indian removal, and negotiated The

Treaty of New Echota,

on December 29, 1835, which granted Cherokee Indians two years to move

to Indian Territory (modern Oklahoma). Only a fraction of the Cherokees

left voluntarily. The U.S. government, with assistance from state

militias, forced most of the remaining Cherokees west in 1838.

[22]

The Cherokees were temporarily remanded in camps in eastern Tennessee.

In November, the Cherokee were broken into groups of around 1,000 each

and began the journey west. They endured heavy rains, snow, and freezing

temperatures.

When the Cherokee negotiated the

Treaty of New Echota,

they exchanged all their land east of the Mississippi for land in

modern Oklahoma and a $5 million payment from the federal government.

Many Cherokee felt betrayed that their leadership accepted the deal, and

over 16,000 Cherokee signed a petition to prevent the passage of the

treaty. By the end of the decade in 1840, tens of thousands of Cherokee

and other tribes had been removed from their land east of the

Mississippi River. The Creek, Choctaw, Seminole, and Chicksaw were also

relocated under the Indian Removal Act of 1830. One Choctaw leader

portrayed the removal as "A Trail of Tears and Deaths", a devastating

event that removed most of the Native population of the southeastern

United States from their traditional homelands.

[23]

Terminology

The latter

forced relocations have sometimes been referred to as "

death marches", in particular with reference to the Cherokee march across the Midwest in 1838, which occurred on a predominantly land route.

[14]

Indians who had the means initially provided for their own removal.

Contingents that were led by conductors from the U.S. Army included

those led by

Edward Deas, who was claimed to be a sympathizer for the Cherokee plight.

[citation needed]

The largest death toll from the Cherokee forced relocation comes from

the period after the May 23, 1838 deadline. This was at the point when

the remaining Cherokee were

rounded into camps and pressed into oversized detachments, often over 700 in size (larger than the populations of

Little Rock or

Memphis

at that time). Communicable diseases spread quickly through these

closely quartered groups, killing many. These contingents were among the

last to move, but following the same routes the others had taken; the

areas they were going through had been depleted of supplies due to the

vast numbers that had gone before them. The marchers were subject to

extortion and violence along the route. In addition, these final

contingents were forced to set out during the hottest and coldest months

of the year, killing many. Exposure to the elements, disease and

starvation, harassment by local frontiersmen, and insufficient rations

similarly killed up to one-third of the Choctaw and other nations on the

march.

[24]

There exists some debate among historians and the affected tribes as

to whether the term "Trail of Tears" should be used to refer to the

entire history of forced relocations from the United States east of the

Mississippi into

Indian Territory (as was the stated U.S. policy), or to the

Five Tribes

described above, to the route of the land march specifically, or to

specific marches in which the remaining holdouts from each area were

rounded up.

Legal background

The territorial boundaries claimed as sovereign and controlled by the

Indian nations living in what were then known as the Indian

Territories—the portion of the early United States west of the

Mississippi River not yet claimed or allotted

to become Oklahoma—were fixed and determined by national treaties with the

United States federal government. These recognized the tribal governments as dependent but internally

sovereign, or

autonomous nations under the sole jurisdiction of the federal government.

While retaining their tribal governance, which included a constitution or official council in tribes such as the

Iroquois and Cherokee, many portions of the southeastern Indian nations had become partially or completely

economically integrated into the economy of the region. This included the plantation economy in states such as

Georgia, and the possession of

slaves. These slaves were also forcibly relocated during the process of removal.

[14] A similar process had occurred earlier in the territories controlled by the

Confederacy of the Six Nations in what is now

upstate New York prior to the British invasion and

subsequent U.S. annexation of the Iroquois nation.

Under the history of U.S. treaty law, the territorial boundaries claimed by

federally recognized tribes received the same status under which the Southeastern tribal claims were recognized; until the following establishment of

reservations of land, determined by the federal government, which were ceded to the remaining tribes by

de jure treaty, in a process that often entailed

forced relocation. The establishment of the

Indian Territory

and the extinguishment of Indian land claims east of the Mississippi

anticipated the establishment of the U.S. Indian reservation system. It

was imposed on remaining Indian lands later in the 19th century.

The statutory argument for Indian sovereignty persisted until the

Supreme Court of the United States ruled in

Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831), that (

e.g.)

the Cherokee were not a sovereign and independent nation, and therefore

not entitled to a hearing before the court. However, in

Worcester v. Georgia

(1832), the court re-established limited internal sovereignty under the

sole jurisdiction of the federal government, in a ruling that both

opposed the subsequent forced relocation and set the basis for modern

U.S. case law.

While the latter ruling was defied by Jackson,

[25]

the actions of the Jackson administration were not isolated because

state and federal officials had violated treaties without consequence,

often attributed to

military exigency, as the members of individual Indian nations were not automatically

United States citizens and were rarely given standing in any U.S. court.

Jackson's involvement in what became known as the Trail of Tears

cannot be ignored. In a speech regarding Indian removal, Jackson said,

"It will separate the Indians from immediate contact with settlements of

whites; free them from the power of the States; enable them to pursue

happiness in their own way and under their own rude institutions; will

retard the progress of decay, which is lessening their numbers, and

perhaps cause them gradually, under the protection of the Government and

through the influence of good counsels, to cast off their savage habits

and become an interesting, civilized, and Christian community.”

According to Jackson, the move would be nothing but beneficial for all

parties. His point of view garnered support from many Americans, many of

whom would benefit economically from the removal.

This was compounded by the fact that while citizenship tests existed

for Indians living in newly annexed areas before and after forced

relocation, individual U.S. states did not recognize tribal land claims,

only individual

title

under State law, and distinguished between the rights of white and

non-white citizens, who often had limited standing in court; and

Indian removal

was carried out under U.S. military jurisdiction, often by state

militias. As a result, individual Indians who could prove U.S.

citizenship were nevertheless displaced from newly annexed areas.

[14] The military actions and subsequent treaties enacted by Jackson's and

Martin Van Buren's administrations pursuant to the 1830 law, which Tennessee Congressman

Davy Crockett had unsuccessfully voted against,

are widely considered to have directly caused the expulsion or death of

a substantial part of the Indians then living in the southeastern

United States.

Choctaw removal

The Choctaw nation occupied large portions of what are now the U.S. states of

Alabama,

Mississippi, and

Louisiana. After a series of treaties starting in 1801, the Choctaw nation was reduced to 11,000,000 acres (45,000 km

2). The

Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek

ceded the remaining country to the United States and was ratified in

early 1831. The removals were only agreed to after a provision in the

Treaty of Dancing Rabbit Creek allowed some Choctaw to remain.

George W. Harkins wrote to the citizens of the United States before the removals were to commence:

It is with considerable diffidence that I attempt to address the

American people, knowing and feeling sensibly my incompetency; and

believing that your highly and well improved minds would not be well

entertained by the address of a Choctaw. But having determined to

emigrate west of the Mississippi river this fall, I have thought proper

in bidding you farewell to make a few remarks expressive of my views,

and the feelings that actuate me on the subject of our removal.... We as

Choctaws rather chose to suffer and be free, than live under the

degrading influence of laws, which our voice could not be heard in their

formation.

— George W. Harkins, George W. Harkins to the American People[27]

United States Secretary of War

Lewis Cass appointed

George Gaines

to manage the removals. Gaines decided to remove Choctaws in three

phases starting in 1831 and ending in 1833. The first was to begin on

November 1, 1831 with groups meeting at Memphis and Vicksburg. A harsh

winter would batter the emigrants with flash floods, sleet, and snow.

Initially the Choctaws were to be transported by wagon but floods halted

them. With food running out, the residents of Vicksburg and Memphis

were concerned. Five steamboats (the Walter Scott, the Brandywine, the

Reindeer, the Talma, and the Cleopatra) would ferry Choctaws to their

river-based destinations. The Memphis group traveled up the Arkansas for

about 60 miles (100 km) to Arkansas Post. There the temperature stayed

below freezing for almost a week with the rivers clogged with ice, so

there could be no travel for weeks. Food rationing consisted of a

handful of boiled corn, one turnip, and two cups of heated water per

day. Forty government wagons were sent to Arkansas Post to transport

them to Little Rock. When they reached Little Rock, a Choctaw chief

referred to their trek as a "

trail of tears and death."

[28] The Vicksburg group was led by an incompetent guide and was lost in the Lake Providence swamps.

Alexis de Tocqueville, the French philosopher, witnessed the Choctaw removals while in

Memphis, Tennessee in 1831,

In the whole scene there was an air of ruin and destruction,

something which betrayed a final and irrevocable adieu; one couldn't

watch without feeling one's heart wrung. The Indians were tranquil, but

sombre and taciturn. There was one who could speak English and of whom I

asked why the Chactas were leaving their country. "To be free," he

answered, could never get any other reason out of him. We ... watch the

expulsion ... of one of the most celebrated and ancient American

peoples.

— Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America[29]

Nearly 17,000 Choctaws made the move to what would be called

Indian Territory and then later

Oklahoma.

[30]

About 2,500–6,000 died along the trail of tears. Approximately

5,000–6,000 Choctaws remained in Mississippi in 1831 after the initial

removal efforts.

[24][31]

The Choctaws who chose to remain in newly formed Mississippi were

subject to legal conflict, harassment, and intimidation. The Choctaws

"have had our habitations torn down and burned, our fences destroyed,

cattle turned into our fields and we ourselves have been scourged,

manacled, fettered and otherwise personally abused, until by such

treatment some of our best men have died."

[31] The Choctaws in Mississippi were later reformed as the

Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians and the removed Choctaws became the

Choctaw Nation of Oklahoma. The Choctaws were the first to sign a removal treaty presented by the federal government. President

Andrew Jackson

wanted strong negotiations with the Choctaws in Mississippi, and the

Choctaws seemed much more cooperative than Andrew Jackson had imagined. When commissioners and Choctaws came to negotiation agreements it was

said the United States would bear the expense of moving their homes and

that they had to be removed within two and a half years of the signed

treaty.

[32]

Seminole resistance

The U.S. acquired Florida from

Spain via the

Adams–Onís Treaty and took possession in 1821. In 1832 the Seminoles were called to a meeting at Payne's Landing on the

Ocklawaha River.

The treaty negotiated called for the Seminoles to move west, if the

land were found to be suitable. They were to be settled on the

Creek

reservation and become part of the Creek tribe, who considered them

deserters; some of the Seminoles had been derived from Creek bands but

also from other tribes. Those among the tribe who once were members of

Creek bands did not wish to move west to where they were certain that

they would meet death for leaving the main band of Creek Indians. The

delegation of seven chiefs who were to inspect the new reservation did

not leave Florida until October 1832. After touring the area for several

months and conferring with the Creeks who had already settled there,

the seven chiefs signed a statement on March 28, 1833 that the new land

was acceptable. Upon their return to Florida, however, most of the

chiefs renounced the statement, claiming that they had not signed it, or

that they had been forced to sign it, and in any case, that they did

not have the power to decide for all the tribes and bands that resided

on the reservation. The villages in the area of the Apalachicola River

were more easily persuaded, however, and went west in 1834.

[33]

On December 28, 1835 a group of Seminoles and blacks ambushed a U.S.

Army company marching from Fort Brooke in Tampa to Fort King in

Ocala, killing all but three of the 110 army troops. This came to be known as the

Dade Massacre.

As the realization that the Seminoles would resist relocation sank

in, Florida began preparing for war. The St. Augustine Militia asked the

War Department for the loan of 500 muskets. Five hundred volunteers were mobilized under Brig. Gen.

Richard K. Call.

Indian war parties raided farms and settlements, and families fled to

forts, large towns, or out of the territory altogether. A war party led

by

Osceola

captured a Florida militia supply train, killing eight of its guards

and wounding six others. Most of the goods taken were recovered by the

militia in another fight a few days later. Sugar plantations along the

Atlantic coast south of St. Augustine were destroyed, with many of the

slaves on the plantations joining the Seminoles.

[34]

Other warchiefs such as

Halleck Tustenuggee, Jumper, and

Black Seminoles

Abraham and John Horse continued the Seminole resistance against the

army. The war ended, after a full decade of fighting, in 1842. The U.S.

government is estimated to have spent about $20,000,000 on the war, at

the time an astronomical sum, and equal to $496,344,828 today. Many

Indians were forcibly exiled to Creek lands west of the Mississippi;

others retreated into the Everglades. In the end, the government gave up

trying to subjugate the Seminole in their Everglades redoubts and left

fewer than 100 Seminoles in peace. However, other scholars state that at

least several hundred Seminoles remained in the Everglades after the

Seminole Wars.

[35][36][37]

As a result of the Seminole Wars, the surviving Seminole band of the

Everglades claims to be the only federally recognized tribe which never

relinquished sovereignty or signed a peace treaty with the United

States.

In general the American people tended to view the Indian resistance as unwarranted. An article published by the Virginia

Enquirer

on January 26, 1836, called the "Hostilities of the Seminoles",

assigned all the blame for the violence that came from the Seminole's

resistance to the Seminoles themselves. The article accuses the Indians

of not staying true to their word—the promises they supposedly made in

the treaties and negotiations from the Indian Removal Act.

[38]

Creek dissolution

After the War of 1812, some Muscogee leaders such as

William McIntosh signed treaties that ceded more land to Georgia. The 1814 signing of the

Treaty of Fort Jackson signaled the end for the Creek Nation and for all Indians in the South.

[39]

Friendly Creek leaders, like Selocta and Big Warrior, addressed Sharp

Knife (the Indian nickname for Andrew Jackson) and reminded him that

they keep the peace. Nevertheless, Jackson retorted that they did not

"cut (

Tecumseh's) throat" when they had the chance, so they must now cede Creek lands. Jackson also ignored Article 9 of the

Treaty of Ghent that restored sovereignty to Indians and their nations.

Jackson opened this first peace session by faintly acknowledging the

help of the friendly Creeks. That done, he turned to the Red Sticks and

admonished them for listening to evil counsel. For their crime, he said,

the entire Creek Nation must pay. He demanded the equivalent of all

expenses incurred by the United States in prosecuting the war, which by

his calculation came to 23,000,000 acres (93,000 km2) of land. - Robert V. Remini, Andrew Jackson[39]

Eventually, the Creek Confederacy enacted a law that made further land cessions a

capital offense. Nevertheless, on February 12, 1825, McIntosh and other chiefs signed the

Treaty of Indian Springs, which gave up most of the remaining Creek lands in Georgia.

[40] After the

U.S. Senate ratified the treaty, McIntosh was assassinated on May 13, 1825, by Creeks led by Menawa.

The Creek National Council, led by

Opothle Yohola, protested to the United States that the Treaty of Indian Springs was fraudulent. President

John Quincy Adams was sympathetic, and eventually the treaty was nullified in a new agreement, the

Treaty of Washington (1826).

[41]

The historian R. Douglas Hurt wrote: "The Creeks had accomplished what

no Indian nation had ever done or would do again — achieve the annulment

of a ratified treaty."

[42]

However, Governor Troup of Georgia ignored the new treaty and began to

forcibly remove the Indians under the terms of the earlier treaty. At

first, President Adams attempted to intervene with federal troops, but

Troup called out the militia, and Adams, fearful of a civil war,

conceded. As he explained to his intimates, "The Indians are not worth

going to war over."

Although the Creeks had been forced from Georgia, with many Lower Creeks moving to the

Indian Territory,

there were still about 20,000 Upper Creeks living in Alabama. However,

the state moved to abolish tribal governments and extend state laws over

the Creeks.

Opothle Yohola appealed to the administration of President Andrew Jackson for protection from Alabama; when none was forthcoming, the

Treaty of Cusseta was signed on March 24, 1832, which divided up Creek lands into individual allotments.

[43]

Creeks could either sell their allotments and receive funds to remove

to the west, or stay in Alabama and submit to state laws. The Creeks

were never given a fair chance to comply with the terms of the treaty,

however. Rampant illegal settlement of their lands by Americans

continued unabated with federal and state authorities unable or

unwilling to do much to halt it. Further, as recently detailed by

historian Billy Winn in his thorough chronicle of the events leading to

removal, a variety of fraudulent schemes designed to cheat the Creeks

out of their allotments, many of them organized by speculators operating

out of Columbus, Georgia and Montgomery, Alabama, were perpetrated

after the signing of the Treaty of Cusseta.

[44]

A portion of the beleaguered Creeks, many desperately poor and feeling

abused and oppressed by their American neighbors, struck back by

carrying out occasional raids on area farms and committing other

isolated acts of violence. Escalating tensions erupted into open war

with the United States following the destruction of the village of

Roanoke, Georgia, located along the Chattahoochee River on the boundary

between Creek and American territory, in May 1836. During the so-called "

Creek War of 1836"

Secretary of War Lewis Cass dispatched General

Winfield Scott

to end the violence by forcibly removing the Creeks to the Indian

Territory west of the Mississippi River. With the Indian Removal Act of

1830 it continued into 1835 and after as in 1836 over 15,000 Creeks were

driven from their land for the last time. 3,500 of those 15,000 Creeks

did not survive the trip to Oklahoma where they eventually settled.

[23]

Chickasaw monetary removal

The Chickasaw received financial compensation from the United States

for their lands east of the Mississippi River. In 1836, the Chickasaws

had reached an agreement to purchase land from the previously removed

Choctaws after a bitter five-year debate. They paid the Choctaws

$530,000 (equal to $11,558,818 today) for the westernmost part of the

Choctaw land. The first group of Chickasaws moved in 1836 and was led by

John M. Millard. The Chickasaws gathered at

Memphis

on July 4, 1836, with all of their assets—belongings, livestock, and

slaves. Once across the Mississippi River, they followed routes

previously established by the Choctaws and the Creeks. Once in

Indian Territory, the Chickasaws merged with the Choctaw nation.

Cherokee forced relocation

Cherokee Principal Chief

John Ross, photographed before his death in 1866

By 1838, about 2,000 Cherokee had voluntarily relocated from Georgia to

Indian Territory (present day Oklahoma). Forcible removals began in May 1838 when General

Winfield Scott received a final order from President

Martin Van Buren to relocate the remaining Cherokees.

[23] Approximately 4,000 Cherokees died in the ensuing trek to Oklahoma.

[45] In the

Cherokee language, the event is called

nu na da ul tsun yi (“the place where they cried”) or

nu na hi du na tlo hi lu i (the trail where they cried). The Cherokee Trail of Tears resulted from the enforcement of the

Treaty of New Echota, an agreement signed under the provisions of the

Indian Removal Act of 1830, which exchanged Indian land in the East for lands west of the

Mississippi River, but which was never accepted by the elected tribal leadership or a majority of the Cherokee people.

The sparsely inhabited Cherokee lands were highly attractive to

Georgian farmers experiencing population pressure, and illegal

settlements resulted. Long-simmering tensions between Georgia and the

Cherokee Nation were brought to a crisis by the discovery of gold near

Dahlonega, Georgia, in 1829, resulting in the

Georgia Gold Rush, the second

gold rush in U.S. history. Hopeful gold speculators began trespassing on Cherokee lands, and pressure mounted to fulfill the

Compact of 1802 in which the US Government promised to extinguish Indian land claims in the state of Georgia.

When Georgia moved to extend state laws over Cherokee lands in 1830, the matter went to the

U.S. Supreme Court. In

Cherokee Nation v. Georgia (1831), the

Marshall court ruled that the

Cherokee Nation was not a sovereign and independent nation, and therefore refused to hear the case. However, in

Worcester v. Georgia

(1832), the Court ruled that Georgia could not impose laws in Cherokee

territory, since only the national government — not state governments —

had authority in Indian affairs.

Worcester v Georgia

is associated with Andrew Jackson's famous, though apocryphal, quote

"John Marshall has made his decision; now let him enforce it!" In

reality, this quote did not appear until 30 years after the incident and

was first printed in a textbook authored by Jackson critic

Horace Greeley.

[18]

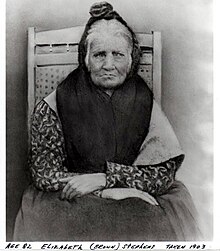

Elizabeth "Betsy" Brown Stephens (1903), a Cherokee Indian who walked the Trail of Tears in 1838

Fearing open warfare between federal troops and the Georgia militia,

Jackson decided not to enforce Cherokee claims against the state of

Georgia. He was already embroiled in a constitutional crisis with

South Carolina (i.e. the

nullification crisis) and favored Cherokee relocation over civil war.

[18] With the

Indian Removal Act of 1830, the

U.S. Congress

had given Jackson authority to negotiate removal treaties, exchanging

Indian land in the East for land west of the Mississippi River. Jackson

used the dispute with Georgia to put pressure on the Cherokees to sign a

removal treaty.

[46]

The final treaty, passed in Congress by a single vote, and signed by

President Andrew Jackson, was imposed by his successor President

Martin Van Buren. Van Buren allowed

Georgia,

Tennessee,

North Carolina, and

Alabama

an armed force of 7,000 militiamen, army regulars, and volunteers under

General Winfield Scott to relocate about 13,000 Cherokees to Cleveland,

Tennessee. After the initial roundup, the U.S. military oversaw the

emigration to Oklahoma. Former Cherokee lands were immediately opened to

settlement. Most of the deaths during the journey were caused by

disease, malnutrition, and exposure during an unusually cold winter.

[47]

In the winter of 1838 the Cherokee began the 1,000-mile (1,600 km)

march with scant clothing and most on foot without shoes or moccasins.

The march began in

Red Clay, Tennessee,

the location of the last Eastern capital of the Cherokee Nation.

Because of the diseases, the Indians were not allowed to go into any

towns or villages along the way; many times this meant traveling much

farther to go around them.

[48] After crossing Tennessee and Kentucky, they arrived at the

Ohio River across from

Golconda in southern Illinois

about the 3rd of December 1838. Here the starving Indians were charged a

dollar a head (equal to $22.49 today) to cross the river on "Berry's

Ferry" which typically charged twelve cents, equal to $2.70 today. They

were not allowed passage until the ferry had serviced all others wishing

to cross and were forced to take shelter under "Mantle Rock," a shelter

bluff on the Kentucky side, until "Berry had nothing better to do".

Many died huddled together at Mantle Rock waiting to cross. Several

Cherokee were murdered by locals. The Cherokee filed a lawsuit against

the U.S. Government through the courthouse in

Vienna, suing the government for $35 a head (equal to $787.17 today) to bury the murdered Cherokee.

[48]

As they crossed southern Illinois, on December 26, Martin Davis,

Commissary Agent for Moses Daniel's detachment, wrote: "There is the

coldest weather in Illinois I ever experienced anywhere. The streams are

all frozen over something like 8 or 12 inches [20 or 30 cm] thick. We

are compelled to cut through the ice to get water for ourselves and

animals. It snows here every two or three days at the fartherest. We are

now camped in Mississippi [River] swamp 4 miles (6 km) from the river,

and there is no possible chance of crossing the river for the numerous

quantity of ice that comes floating down the river every day. We have

only traveled 65 miles (105 km) on the last month, including the time

spent at this place, which has been about three weeks. It is unknown

when we shall cross the river...."

[49]

I fought through the War Between the States and have seen many men

shot, but the Cherokee Removal was the cruelest work I ever knew.

— Georgian soldier who participated in the removal[50]

A Trail of Tears map of Southern Illinois from the USDA - U.S. Forest Service

It eventually took almost three months to cross the 60 miles (97 kilometres) on land between the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers.

[51]

The trek through southern Illinois is where the Cherokee suffered most

of their deaths. However a few years before forced removal, some

Cherokee who opted to leave their homes voluntarily chose a water-based

route through the Tennessee, Ohio and Mississippi rivers. It took only

21 days, but the Cherokee who were forcibly relocated were weary of

water travel.

[52]

Removed Cherokees initially settled near

Tahlequah, Oklahoma. When signing the

Treaty of New Echota in 1835 Major Ridge said "I have signed my death warrant." The resulting political turmoil led to the killings of

Major Ridge,

John Ridge, and

Elias Boudinot; of the leaders of the Treaty Party, only

Stand Watie escaped death.

[53][54][55]

The population of the Cherokee Nation eventually rebounded, and today

the Cherokees are the largest American Indian group in the United

States.

[56]

There were some exceptions to removal. Perhaps 100 Cherokees evaded

the U.S. soldiers and lived off the land in Georgia and other states.

Those Cherokees who lived on private, individually owned lands (rather

than communally owned tribal land) were not subject to removal. In North

Carolina, about 400 Cherokees, known as the Oconaluftee Cherokee, lived

on land in the

Great Smoky Mountains owned by a white man named

William Holland Thomas

(who had been adopted by Cherokees as a boy), and were thus not subject

to removal. Added to this were some 200 Cherokee from the Nantahala

area allowed to stay in the

Qualla Boundary after assisting the U.S. Army in hunting down and capturing the family of the old prophet,

Tsali. (Tsali faced a firing squad.) These North Carolina Cherokees became the

Eastern Band of the Cherokee Nation.

Landmarks and references

Map of National Historic trails

In 1987, about 2,200 miles (3,500 km) of trails were authorized by

federal law to mark the removal of 17 detachments of the Cherokee

people.

[57] Called the "Trail of Tears

National Historic Trail," it traverses portions of nine states and includes land and water routes.

[58]

Trail of Tears outdoor historical drama, Unto These Hills

An historical drama based on the Trail of Tears,

Unto These Hills written by

Kermit Hunter,

has sold over five million tickets for its performances since its

opening on July 1, 1950, both touring and at the outdoor Mountainside

Theater of the Cherokee Historical Association in

Cherokee, North Carolina.

[59][60]

Commemorative medallion

Cherokee artist Troy Anderson was commissioned to design the

Cherokee Trail of Tears Sesquicentennial Commemorative Medallion. The falling-tear medallion shows a seven-pointed star, the symbol of the seven clans of the Cherokees.

[61]

In literature and oral history

- Family Stories From the Trail of Tears is a collection edited by Lorrie Montiero and transcribed by Grant Foreman, taken from the Indian-Pioneer History Collection[62]

- Walking the Trail (1991) is a book by Jerry Ellis describing his 900-mile walk retracing of the Trail of Tears in reverse