Detail from Raphael's The School of Athens featuring a Greek mathematician – perhaps representing Euclid or Archimedes – using a compass to draw a geometric construction.

Euclidean geometry is a mathematical system attributed to Alexandrian Greek mathematician Euclid, which he described in his textbook on geometry: the Elements. Euclid's method consists in assuming a small set of intuitively appealing axioms, and deducing many other propositions (theorems) from these. Although many of Euclid's results had been stated by earlier mathematicians, Euclid was the first to show how these propositions could fit into a comprehensive deductive and logical system. The Elements begins with plane geometry, still taught in secondary school (High School) as the first axiomatic system and the first examples of formal proof. It goes on to the solid geometry of three dimensions. Much of the Elements states results of what are now called algebra and number theory, explained in geometrical language.

For more than two thousand years, the adjective "Euclidean" was

unnecessary because no other sort of geometry had been conceived.

Euclid's axioms seemed so intuitively obvious (with the possible

exception of the parallel postulate) that any theorem proved from them was deemed true in an absolute, often metaphysical, sense. Today, however, many other self-consistent non-Euclidean geometries are known, the first ones having been discovered in the early 19th century. An implication of Albert Einstein's theory of general relativity is that physical space itself is not Euclidean, and Euclidean space is a good approximation for it only over short distances (relative to the strength of the gravitational field).

Euclidean geometry is an example of synthetic geometry,

in that it proceeds logically from axioms describing basic properties

of geometric objects such as points and lines, to propositions about

those objects, all without the use of coordinates to specify those objects. This is in contrast to analytic geometry, which uses coordinates to translate geometric propositions into algebraic formulas.

The Elements

The Elements is mainly a systematization of earlier knowledge

of geometry. Its improvement over earlier treatments was rapidly

recognized, with the result that there was little interest in preserving

the earlier ones, and they are now nearly all lost.

There are 13 books in the Elements:

Books I–IV and VI discuss plane geometry. Many results about

plane figures are proved, for example "In any triangle two angles taken

together in any manner are less than two right angles." (Book 1

proposition 17 ) and the Pythagorean theorem

"In right angled triangles the square on the side subtending the right

angle is equal to the squares on the sides containing the right angle."

(Book I, proposition 47)

Books V and VII–X deal with number theory, with numbers treated geometrically as lengths of line segments or areas of regions. Notions such as prime numbers and rational and irrational numbers are introduced. It is proved that there are infinitely many prime numbers.

Books XI–XIII concern solid geometry. A typical result is the 1:3 ratio between the volume of a cone and a cylinder with the same height and base. The platonic solids are constructed.

Axioms

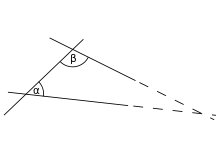

The

parallel postulate (Postulate 5): If two lines intersect a third in

such a way that the sum of the inner angles on one side is less than two

right angles, then the two lines inevitably must intersect each other

on that side if extended far enough.

Euclidean geometry is an axiomatic system, in which all theorems ("true statements") are derived from a small number of simple axioms. Until the advent of non-Euclidean geometry,

these axioms were considered to be obviously true in the physical

world, so that all the theorems would be equally true. However, Euclid's

reasoning from assumptions to conclusions remains valid independent of

their physical reality.

Near the beginning of the first book of the Elements, Euclid gives five postulates (axioms) for plane geometry, stated in terms of constructions (as translated by Thomas Heath):

- Let the following be postulated:

- To draw a straight line from any point to any point.

- To produce [extend] a finite straight line continuously in a straight line.

- To describe a circle with any centre and distance [radius].

- That all right angles are equal to one another.

- [The parallel postulate]: That, if a straight line falling on two straight lines make the interior angles on the same side less than two right angles, the two straight lines, if produced indefinitely, meet on that side on which the angles are less than two right angles.

Although Euclid only explicitly asserts the existence of the

constructed objects, in his reasoning they are implicitly assumed to be

unique.

The Elements also include the following five "common notions":

- Things that are equal to the same thing are also equal to one another (the Transitive property of a Euclidean relation).

- If equals are added to equals, then the wholes are equal (Addition property of equality).

- If equals are subtracted from equals, then the differences are equal (Subtraction property of equality).

- Things that coincide with one another are equal to one another (Reflexive Property).

- The whole is greater than the part.

Modern scholars agree that Euclid's postulates do not provide the

complete logical foundation that Euclid required for his presentation. Modern treatments use more extensive and complete sets of axioms.

Parallel postulate

To the ancients, the parallel postulate seemed less obvious than the

others. They aspired to create a system of absolutely certain

propositions, and to them it seemed as if the parallel line postulate

required proof from simpler statements. It is now known that such a

proof is impossible, since one can construct consistent systems of

geometry (obeying the other axioms) in which the parallel postulate is

true, and others in which it is false.

Euclid himself seems to have considered it as being qualitatively

different from the others, as evidenced by the organization of the Elements: his first 28 propositions are those that can be proved without it.

Many alternative axioms can be formulated which are logically equivalent to the parallel postulate (in the context of the other axioms). For example, Playfair's axiom states:

- In a plane, through a point not on a given straight line, at most one line can be drawn that never meets the given line.

The "at most" clause is all that is needed since it can be proved

from the remaining axioms that at least one parallel line exists.

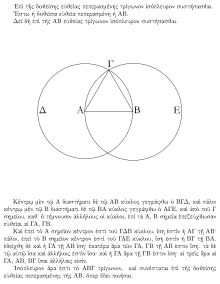

A proof from Euclid's Elements

that, given a line segment, one may construct an equilateral triangle

that includes the segment as one of its sides: an equilateral triangle

ΑΒΓ is made by drawing circles Δ and Ε centered on the points Α and Β,

and taking one intersection of the circles as the third vertex of the

triangle.

Methods of proof

Euclidean Geometry is constructive.

Postulates 1, 2, 3, and 5 assert the existence and uniqueness of

certain geometric figures, and these assertions are of a constructive

nature: that is, we are not only told that certain things exist, but are

also given methods for creating them with no more than a compass and an unmarked straightedge. In this sense, Euclidean geometry is more concrete than many modern axiomatic systems such as set theory,

which often assert the existence of objects without saying how to

construct them, or even assert the existence of objects that cannot be

constructed within the theory. Strictly speaking, the lines on paper are models

of the objects defined within the formal system, rather than instances

of those objects. For example, a Euclidean straight line has no width,

but any real drawn line will. Though nearly all modern mathematicians

consider nonconstructive methods

just as sound as constructive ones, Euclid's constructive proofs often

supplanted fallacious nonconstructive ones—e.g., some of the

Pythagoreans' proofs that involved irrational numbers, which usually

required a statement such as "Find the greatest common measure of ..."

Euclid often used proof by contradiction.

Euclidean geometry also allows the method of superposition, in which a

figure is transferred to another point in space. For example,

proposition I.4, side-angle-side congruence of triangles, is proved by

moving one of the two triangles so that one of its sides coincides with

the other triangle's equal side, and then proving that the other sides

coincide as well. Some modern treatments add a sixth postulate, the

rigidity of the triangle, which can be used as an alternative to

superposition.

System of measurement and arithmetic

Euclidean geometry has two fundamental types of measurements: angle and distance. The angle scale is absolute, and Euclid uses the right angle as his basic unit, so that, e.g., a 45-degree

angle would be referred to as half of a right angle. The distance scale

is relative; one arbitrarily picks a line segment with a certain

nonzero length as the unit, and other distances are expressed in

relation to it. Addition of distances is represented by a construction

in which one line segment is copied onto the end of another line segment

to extend its length, and similarly for subtraction.

Measurements of area and volume are derived from distances. For example, a rectangle

with a width of 3 and a length of 4 has an area that represents the

product, 12. Because this geometrical interpretation of multiplication

was limited to three dimensions, there was no direct way of interpreting

the product of four or more numbers, and Euclid avoided such products,

although they are implied, e.g., in the proof of book IX, proposition

20.

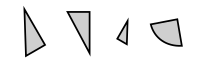

An example of congruence. The two figures on the left are congruent, while the third is similar

to them. The last figure is neither. Congruences alter some properties,

such as location and orientation, but leave others unchanged, like distance and angles. The latter sort of properties are called invariants and studying them is the essence of geometry.

Euclid refers to a pair of lines, or a pair of planar or solid

figures, as "equal" (ἴσος) if their lengths, areas, or volumes are

equal, and similarly for angles. The stronger term "congruent"

refers to the idea that an entire figure is the same size and shape as

another figure. Alternatively, two figures are congruent if one can be

moved on top of the other so that it matches up with it exactly.

(Flipping it over is allowed.) Thus, for example, a 2x6 rectangle and a

3x4 rectangle are equal but not congruent, and the letter R is congruent

to its mirror image. Figures that would be congruent except for their

differing sizes are referred to as similar. Corresponding angles in a pair of similar shapes are congruent and corresponding sides are in proportion to each other.

Notation and terminology

Naming of points and figures

Points

are customarily named using capital letters of the alphabet. Other

figures, such as lines, triangles, or circles, are named by listing a

sufficient number of points to pick them out unambiguously from the

relevant figure, e.g., triangle ABC would typically be a triangle with

vertices at points A, B, and C.

Complementary and supplementary angles

Angles whose sum is a right angle are called complementary.

Complementary angles are formed when a ray shares the same vertex and

is pointed in a direction that is in between the two original rays that

form the right angle. The number of rays in between the two original

rays is infinite.

Angles whose sum is a straight angle are supplementary.

Supplementary angles are formed when a ray shares the same vertex and

is pointed in a direction that is in between the two original rays that

form the straight angle (180 degree angle). The number of rays in

between the two original rays is infinite.

Modern versions of Euclid's notation

Modern school textbooks often define separate figures called lines (infinite), rays (semi-infinite), and line segments

(of finite length). Euclid, rather than discussing a ray as an object

that extends to infinity in one direction, would normally use locutions

such as "if the line is extended to a sufficient length," although he

occasionally referred to "infinite lines". A "line" in Euclid could be

either straight or curved, and he used the more specific term "straight

line" when necessary.

Some important or well known results

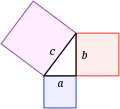

- The Pons Asinorum or Bridge of Asses theorem states that in an isosceles triangle, α = β and γ = δ.

- The Pythagorean theorem states that the sum of the areas of the two squares on the legs (a and b) of a right triangle equals the area of the square on the hypotenuse (c).

- Thales' theorem states that if AC is a diameter, then the angle at B is a right angle.

Pons Asinorum

The Bridge of Asses (Pons Asinorum) states that in

isosceles triangles the angles at the base equal one another, and, if

the equal straight lines are produced further, then the angles under the

base equal one another. Its name may be attributed to its frequent role as the first real test in the Elements

of the intelligence of the reader and as a bridge to the harder

propositions that followed. It might also be so named because of the

geometrical figure's resemblance to a steep bridge that only a

sure-footed donkey could cross.

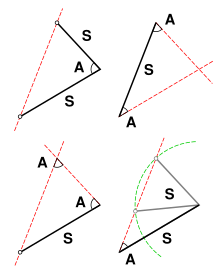

Congruence of triangles

Congruence

of triangles is determined by specifying two sides and the angle

between them (SAS), two angles and the side between them (ASA) or two

angles and a corresponding adjacent side (AAS). Specifying two sides and

an adjacent angle (SSA), however, can yield two distinct possible

triangles unless the angle specified is a right angle.

Triangles are congruent if they have all three sides equal (SSS), two

sides and the angle between them equal (SAS), or two angles and a side

equal (ASA) (Book I, propositions 4, 8, and 26). Triangles with three

equal angles (AAA) are similar, but not necessarily congruent. Also,

triangles with two equal sides and an adjacent angle are not necessarily

equal or congruent.

Triangle angle sum

The sum of the angles of a triangle is equal to a straight angle (180 degrees).

This causes an equilateral triangle to have three interior angles of 60

degrees. Also, it causes every triangle to have at least two acute

angles and up to one obtuse or right angle.

Pythagorean theorem

The celebrated Pythagorean theorem

(book I, proposition 47) states that in any right triangle, the area of

the square whose side is the hypotenuse (the side opposite the right

angle) is equal to the sum of the areas of the squares whose sides are

the two legs (the two sides that meet at a right angle).

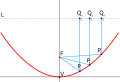

Thales' theorem

Thales' theorem, named after Thales of Miletus

states that if A, B, and C are points on a circle where the line AC is a

diameter of the circle, then the angle ABC is a right angle. Cantor

supposed that Thales proved his theorem by means of Euclid Book I, Prop.

32 after the manner of Euclid Book III, Prop. 31.

Scaling of area and volume

In modern terminology, the area of a plane figure is proportional to the square of any of its linear dimensions, , and the volume of a solid to the cube, . Euclid proved these results in various special cases such as the area of a circle and the volume of a parallelepipedal solid. Euclid determined some, but not all, of the relevant constants of proportionality. E.g., it was his successor Archimedes who proved that a sphere has 2/3 the volume of the circumscribing cylinder.

Applications

Because of Euclidean geometry's fundamental status in mathematics, it

is impractical to give more than a representative sampling of

applications here.

- A surveyor uses a level

- Sphere packing applies to a stack of oranges.

As suggested by the etymology of the word, one of the earliest reasons for interest in geometry was surveying,

and certain practical results from Euclidean geometry, such as the

right-angle property of the 3-4-5 triangle, were used long before they

were proved formally.

The fundamental types of measurements in Euclidean geometry are

distances and angles, both of which can be measured directly by a

surveyor. Historically, distances were often measured by chains, such as

Gunter's chain, and angles using graduated circles and, later, the theodolite.

An application of Euclidean solid geometry is the determination of packing arrangements, such as the problem of finding the most efficient packing of spheres in n dimensions. This problem has applications in error detection and correction.

Geometric optics uses Euclidean geometry to analyze the focusing of light by lenses and mirrors.

Geometry is used extensively in architecture.

Geometry can be used to design origami. Some classical construction problems of geometry are impossible using compass and straightedge, but can be solved using origami.

Quite a lot of CAD (computer-aided design) and CAM (computer-aided manufacturing)

is based on Euclidean geometry. Design geometry typically consists of

shapes bounded by planes, cylinders, cones, tori, etc. CAD/CAM is

essential in the design of almost everything, nowadays, including cars,

airplanes, ships, and the iPhone. A few decades ago, sophisticated

draftsmen learned some fairly advanced Euclidean geometry, including

things like Pascal's theorem and Brianchon's theorem. But now they don't

have to, because the geometric constructions are all done by CAD

programs.

As a description of the structure of space

Euclid believed that his axioms

were self-evident statements about physical reality. Euclid's proofs

depend upon assumptions perhaps not obvious in Euclid's fundamental

axioms,

in particular that certain movements of figures do not change their

geometrical properties such as the lengths of sides and interior angles,

the so-called Euclidean motions, which include translations, reflections and rotations of figures.

Taken as a physical description of space, postulate 2 (extending a

line) asserts that space does not have holes or boundaries (in other

words, space is homogeneous and unbounded); postulate 4 (equality of right angles) says that space is isotropic and figures may be moved to any location while maintaining congruence; and postulate 5 (the parallel postulate) that space is flat (has no intrinsic curvature).

As discussed in more detail below, Einstein's theory of relativity significantly modifies this view.

The ambiguous character of the axioms as originally formulated by

Euclid makes it possible for different commentators to disagree about

some of their other implications for the structure of space, such as

whether or not it is infinite (see below) and what its topology is. Modern, more rigorous reformulations of the system

typically aim for a cleaner separation of these issues. Interpreting

Euclid's axioms in the spirit of this more modern approach, axioms 1-4

are consistent with either infinite or finite space (as in elliptic geometry), and all five axioms are consistent with a variety of topologies (e.g., a plane, a cylinder, or a torus for two-dimensional Euclidean geometry).

Later work

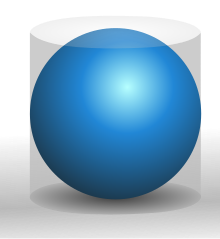

Archimedes and Apollonius

A

sphere has 2/3 the volume and surface area of its circumscribing

cylinder. A sphere and cylinder were placed on the tomb of Archimedes at

his request.

Archimedes

(c. 287 BCE – c. 212 BCE), a colorful figure about whom many historical

anecdotes are recorded, is remembered along with Euclid as one of the

greatest of ancient mathematicians. Although the foundations of his work

were put in place by Euclid, his work, unlike Euclid's, is believed to

have been entirely original. He proved equations for the volumes and areas of various figures in two and three dimensions, and enunciated the Archimedean property of finite numbers.

Apollonius of Perga (c. 262 BCE – c. 190 BCE) is mainly known for his investigation of conic sections.

René Descartes. Portrait after Frans Hals, 1648.

17th century: Descartes

René Descartes (1596–1650) developed analytic geometry, an alternative method for formalizing geometry which focused on turning geometry into algebra.

In this approach, a point on a plane is represented by its Cartesian (x, y) coordinates, a line is represented by its equation, and so on.

In Euclid's original approach, the Pythagorean theorem

follows from Euclid's axioms. In the Cartesian approach, the axioms are

the axioms of algebra, and the equation expressing the Pythagorean

theorem is then a definition of one of the terms in Euclid's axioms,

which are now considered theorems.

The equation

defining the distance between two points P = (px, py) and Q = (qx, qy) is then known as the Euclidean metric, and other metrics define non-Euclidean geometries.

In terms of analytic geometry, the restriction of classical

geometry to compass and straightedge constructions means a restriction

to first- and second-order equations, e.g., y = 2x + 1 (a line), or x2 + y2 = 7 (a circle).

Also in the 17th century, Girard Desargues, motivated by the theory of perspective,

introduced the concept of idealized points, lines, and planes at

infinity. The result can be considered as a type of generalized

geometry, projective geometry, but it can also be used to produce proofs in ordinary Euclidean geometry in which the number of special cases is reduced.

Squaring

the circle: the areas of this square and this circle are equal. In

1882, it was proven that this figure cannot be constructed in a finite

number of steps with an idealized compass and straightedge.

18th century

Geometers

of the 18th century struggled to define the boundaries of the Euclidean

system. Many tried in vain to prove the fifth postulate from the first

four. By 1763, at least 28 different proofs had been published, but all

were found incorrect.

Leading up to this period, geometers also tried to determine what

constructions could be accomplished in Euclidean geometry. For example,

the problem of trisecting an angle

with a compass and straightedge is one that naturally occurs within the

theory, since the axioms refer to constructive operations that can be

carried out with those tools. However, centuries of efforts failed to

find a solution to this problem, until Pierre Wantzel published a proof in 1837 that such a construction was impossible. Other constructions that were proved impossible include doubling the cube and squaring the circle.

In the case of doubling the cube, the impossibility of the construction

originates from the fact that the compass and straightedge method

involve equations whose order is an integral power of two, while doubling a cube requires the solution of a third-order equation.

Euler discussed a generalization of Euclidean geometry called affine geometry,

which retains the fifth postulate unmodified while weakening postulates

three and four in a way that eliminates the notions of angle (whence

right triangles become meaningless) and of equality of length of line

segments in general (whence circles become meaningless) while retaining

the notions of parallelism as an equivalence relation between lines, and

equality of length of parallel line segments (so line segments continue

to have a midpoint).

19th century and non-Euclidean geometry

In the early 19th century, Carnot and Möbius systematically developed the use of signed angles and line segments as a way of simplifying and unifying results.

The century's most significant development in geometry occurred when, around 1830, János Bolyai and Nikolai Ivanovich Lobachevsky separately published work on non-Euclidean geometry, in which the parallel postulate is not valid.

Since non-Euclidean geometry is provably relatively consistent with

Euclidean geometry, the parallel postulate cannot be proved from the

other postulates.

In the 19th century, it was also realized that Euclid's ten

axioms and common notions do not suffice to prove all of the theorems

stated in the Elements. For example, Euclid assumed implicitly

that any line contains at least two points, but this assumption cannot

be proved from the other axioms, and therefore must be an axiom itself.

The very first geometric proof in the Elements, shown in the

figure above, is that any line segment is part of a triangle; Euclid

constructs this in the usual way, by drawing circles around both

endpoints and taking their intersection as the third vertex.

His axioms, however, do not guarantee that the circles actually

intersect, because they do not assert the geometrical property of

continuity, which in Cartesian terms is equivalent to the completeness property of the real numbers. Starting with Moritz Pasch in 1882, many improved axiomatic systems for geometry have been proposed, the best known being those of Hilbert, George Birkhoff, and Tarski.

20th century and general relativity

A

disproof of Euclidean geometry as a description of physical space. In a

1919 test of the general theory of relativity, stars (marked with short

horizontal lines) were photographed during a solar eclipse.

The rays of starlight were bent by the Sun's gravity on their way to

the earth. This is interpreted as evidence in favor of Einstein's

prediction that gravity would cause deviations from Euclidean geometry.

Einstein's theory of general relativity shows that the true geometry of spacetime is not Euclidean geometry.

For example, if a triangle is constructed out of three rays of light,

then in general the interior angles do not add up to 180 degrees due to

gravity. A relatively weak gravitational field, such as the Earth's or

the sun's, is represented by a metric that is approximately, but not

exactly, Euclidean. Until the 20th century, there was no technology

capable of detecting the deviations from Euclidean geometry, but

Einstein predicted that such deviations would exist. They were later

verified by observations such as the slight bending of starlight by the

Sun during a solar eclipse in 1919, and such considerations are now an

integral part of the software that runs the GPS system.

It is possible to object to this interpretation of general relativity

on the grounds that light rays might be improper physical models of

Euclid's lines, or that relativity could be rephrased so as to avoid the

geometrical interpretations. However, one of the consequences of

Einstein's theory is that there is no possible physical test that can

distinguish between a beam of light as a model of a geometrical line and

any other physical model. Thus, the only logical possibilities are to

accept non-Euclidean geometry as physically real, or to reject the

entire notion of physical tests of the axioms of geometry, which can

then be imagined as a formal system without any intrinsic real-world

meaning.

Treatment of infinity

Infinite objects

Euclid sometimes distinguished explicitly between "finite lines" (e.g., Postulate 2) and "infinite

lines" (book I, proposition 12). However, he typically did not make

such distinctions unless they were necessary. The postulates do not

explicitly refer to infinite lines, although for example some

commentators interpret postulate 3, existence of a circle with any

radius, as implying that space is infinite.

The notion of infinitesimal quantities had previously been discussed extensively by the Eleatic School, but nobody had been able to put them on a firm logical basis, with paradoxes such as Zeno's paradox occurring that had not been resolved to universal satisfaction. Euclid used the method of exhaustion rather than infinitesimals.

Later ancient commentators, such as Proclus

(410–485 CE), treated many questions about infinity as issues demanding

proof and, e.g., Proclus claimed to prove the infinite divisibility of a

line, based on a proof by contradiction in which he considered the

cases of even and odd numbers of points constituting it.

At the turn of the 20th century, Otto Stolz, Paul du Bois-Reymond, Giuseppe Veronese, and others produced controversial work on non-Archimedean models of Euclidean geometry, in which the distance between two points may be infinite or infinitesimal, in the Newton–Leibniz sense. Fifty years later, Abraham Robinson provided a rigorous logical foundation for Veronese's work.

Infinite processes

One

reason that the ancients treated the parallel postulate as less certain

than the others is that verifying it physically would require us to

inspect two lines to check that they never intersected, even at some

very distant point, and this inspection could potentially take an

infinite amount of time.

The modern formulation of proof by induction

was not developed until the 17th century, but some later commentators

consider it implicit in some of Euclid's proofs, e.g., the proof of the

infinitude of primes.

Supposed paradoxes involving infinite series, such as Zeno's paradox, predated Euclid. Euclid avoided such discussions, giving, for example, the expression for the partial sums of the geometric series in IX.35 without commenting on the possibility of letting the number of terms become infinite.

Logical basis

Classical logic

Euclid frequently used the method of proof by contradiction, and therefore the traditional presentation of Euclidean geometry assumes classical logic,

in which every proposition is either true or false, i.e., for any

proposition P, the proposition "P or not P" is automatically true.

Modern standards of rigor

Placing Euclidean geometry on a solid axiomatic basis was a preoccupation of mathematicians for centuries. The role of primitive notions, or undefined concepts, was clearly put forward by Alessandro Padoa of the Peano delegation at the 1900 Paris conference:

...when we begin to formulate the theory, we can imagine that the undefined symbols are completely devoid of meaning and that the unproved propositions are simply conditions imposed upon the undefined symbols.

Then, the system of ideas that we have initially chosen is simply one interpretation of the undefined symbols; but..this interpretation can be ignored by the reader, who is free to replace it in his mind by another interpretation.. that satisfies the conditions...

Logical questions thus become completely independent of empirical or psychological questions...

The system of undefined symbols can then be regarded as the abstraction obtained from the specialized theories that result when...the system of undefined symbols is successively replaced by each of the interpretations...

— Padoa, Essai d'une théorie algébrique des nombre entiers, avec une Introduction logique à une théorie déductive quelconque

That is, mathematics is context-independent knowledge within a hierarchical framework. As said by Bertrand Russell:

If our hypothesis is about anything, and not about some one or more particular things, then our deductions constitute mathematics. Thus, mathematics may be defined as the subject in which we never know what we are talking about, nor whether what we are saying is true.

— Bertrand Russell, Mathematics and the metaphysicians

Such foundational approaches range between foundationalism and formalism.

Axiomatic formulations

Geometry is the science of correct reasoning on incorrect figures.

— George Polyá, How to Solve It, p. 208

- Euclid's axioms: In his dissertation to Trinity College, Cambridge, Bertrand Russell summarized the changing role of Euclid's geometry in the minds of philosophers up to that time. It was a conflict between certain knowledge, independent of experiment, and empiricism, requiring experimental input. This issue became clear as it was discovered that the parallel postulate was not necessarily valid and its applicability was an empirical matter, deciding whether the applicable geometry was Euclidean or non-Euclidean.

- Hilbert's axioms: Hilbert's axioms had the goal of identifying a simple and complete set of independent axioms from which the most important geometric theorems could be deduced. The outstanding objectives were to make Euclidean geometry rigorous (avoiding hidden assumptions) and to make clear the ramifications of the parallel postulate.

- Birkhoff's axioms: Birkhoff proposed four postulates for Euclidean geometry that can be confirmed experimentally with scale and protractor. This system relies heavily on the properties of the real numbers. The notions of angle and distance become primitive concepts.

- Tarski's axioms: Alfred Tarski (1902–1983) and his students defined elementary Euclidean geometry as the geometry that can be expressed in first-order logic and does not depend on set theory for its logical basis, in contrast to Hilbert's axioms, which involve point sets. Tarski proved that his axiomatic formulation of elementary Euclidean geometry is consistent and complete in a certain sense: there is an algorithm that, for every proposition, can be shown either true or false. (This doesn't violate Gödel's theorem, because Euclidean geometry cannot describe a sufficient amount of arithmetic for the theorem to apply.) This is equivalent to the decidability of real closed fields, of which elementary Euclidean geometry is a model.

Constructive approaches and pedagogy

The process of abstract axiomatization as exemplified by Hilbert's axioms reduces geometry to theorem proving or predicate logic. In contrast, the Greeks used construction postulates, and emphasized problem solving.

For the Greeks, constructions are more primitive than existence

propositions, and can be used to prove existence propositions, but not vice versa. To describe problem solving adequately requires a richer system of logical concepts. The contrast in approach may be summarized:

- Axiomatic proof: Proofs are deductive derivations of propositions from primitive premises that are ‘true’ in some sense. The aim is to justify the proposition.

- Analytic proof: Proofs are non-deductive derivations of hypotheses from problems. The aim is to find hypotheses capable of giving a solution to the problem. One can argue that Euclid's axioms were arrived upon in this manner. In particular, it is thought that Euclid felt the parallel postulate was forced upon him, as indicated by his reluctance to make use of it, and his arrival upon it by the method of contradiction.

Andrei Nicholaevich Kolmogorov proposed a problem solving basis for geometry. This work was a precursor of a modern formulation in terms of constructive type theory. This development has implications for pedagogy as well.

If proof simply follows conviction of truth rather than contributing to its construction and is only experienced as a demonstration of something already known to be true, it is likely to remain meaningless and purposeless in the eyes of students.— Celia Hoyles, The curricular shaping of students' approach to proof