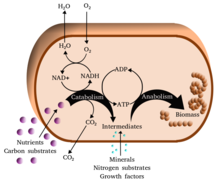

Simplified view of the cellular metabolism

Structure of adenosine triphosphate (ATP), a central intermediate in ENERGY metabolism

Metabolism (/məˈtæbəlɪzəm/, from Greek: μεταβολή metabolē, "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main purposes of metabolism are: the conversion of food to energy to run cellular processes; the conversion of food/fuel to building blocks for proteins, lipids, nucleic acids, and some carbohydrates; and the elimination of nitrogenous wastes. These enzyme-catalyzed

reactions allow organisms to grow and reproduce, maintain their

structures, and respond to their environments. (The word metabolism can

also refer to the sum of all chemical reactions that occur in living

organisms, including digestion

and the transport of substances into and between different cells, in

which case the above described set of reactions within the cells is

called intermediary metabolism or intermediate metabolism).

Metabolic reactions may be categorized as catabolic - the breaking down of compounds (for example, the breaking down of glucose to pyruvate by cellular respiration); or anabolic - the building up (synthesis)

of compounds (such as proteins, carbohydrates, lipids, and nucleic

acids). Usually, catabolism releases energy, and anabolism consumes

energy.

The chemical reactions of metabolism are organized into metabolic pathways,

in which one chemical is transformed through a series of steps into

another chemical, each step being facilitated by a specific enzyme. Enzymes are crucial to metabolism because they allow organisms to drive desirable reactions that require energy that will not occur by themselves, by coupling them to spontaneous reactions that release energy. Enzymes act as catalysts - they allow a reaction to proceed more rapidly - and they also allow the regulation of the rate of a metabolic reaction, for example in response to changes in the cell's environment or to signals from other cells.

The metabolic system of a particular organism determines which substances it will find nutritious and which poisonous. For example, some prokaryotes use hydrogen sulfide as a nutrient, yet this gas is poisonous to animals. The basal metabolic rate of an organism is the measure of the amount of energy consumed by all of these chemical reactions.

A striking feature of metabolism is the similarity of the basic metabolic pathways among vastly different species. For example, the set of carboxylic acids that are best known as the intermediates in the citric acid cycle are present in all known organisms, being found in species as diverse as the unicellular bacterium Escherichia coli and huge multicellular organisms like elephants. These similarities in metabolic pathways are likely due to their early appearance in evolutionary history, and their retention because of their efficacy.

Key biochemicals

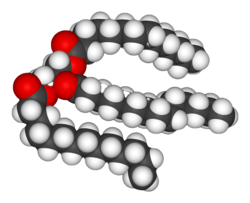

Structure of a triacylglycerol lipid

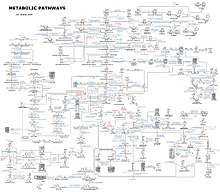

This is a diagram depicting a large set of human metabolic pathways.

Most of the structures that make up animals, plants and microbes are made from three basic classes of molecule: amino acids, carbohydrates and lipids (often called fats).

As these molecules are vital for life, metabolic reactions either focus

on making these molecules during the construction of cells and tissues,

or by breaking them down and using them as a source of energy, by their

digestion. These biochemicals can be joined together to make polymers such as DNA and proteins, essential macromolecules of life.

| Type of molecule | Name of monomer forms | Name of polymer forms | Examples of polymer forms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amino acids | Amino acids | Proteins (made of polypeptides) | Fibrous proteins and globular proteins |

| Carbohydrates | Monosaccharides | Polysaccharides | Starch, glycogen and cellulose |

| Nucleic acids | Nucleotides | Polynucleotides | DNA and RNA |

Amino acids and proteins

Proteins are made of amino acids arranged in a linear chain joined together by peptide bonds. Many proteins are enzymes that catalyze the chemical reactions in metabolism. Other proteins have structural or mechanical functions, such as those that form the cytoskeleton, a system of scaffolding that maintains the cell shape. Proteins are also important in cell signaling, immune responses, cell adhesion, active transport across membranes, and the cell cycle. Amino acids also contribute to cellular energy metabolism by providing a carbon source for entry into the citric acid cycle (tricarboxylic acid cycle), especially when a primary source of energy, such as glucose, is scarce, or when cells undergo metabolic stress.

Lipids

Lipids are the most diverse group of biochemicals. Their main structural uses are as part of biological membranes both internal and external, such as the cell membrane, or as a source of energy. Lipids are usually defined as hydrophobic or amphipathic biological molecules but will dissolve in organic solvents such as benzene or chloroform. The fats are a large group of compounds that contain fatty acids and glycerol; a glycerol molecule attached to three fatty acid esters is called a triacylglyceride. Several variations on this basic structure exist, including alternate backbones such as sphingosine in the sphingolipids, and hydrophilic groups such as phosphate as in phospholipids. Steroids such as cholesterol are another major class of lipids.

Carbohydrates

Glucose can exist in both a straight-chain and ring form.

Carbohydrates are aldehydes or ketones, with many hydroxyl

groups attached, that can exist as straight chains or rings.

Carbohydrates are the most abundant biological molecules, and fill

numerous roles, such as the storage and transport of energy (starch, glycogen) and structural components (cellulose in plants, chitin in animals). The basic carbohydrate units are called monosaccharides and include galactose, fructose, and most importantly glucose. Monosaccharides can be linked together to form polysaccharides in almost limitless ways.

Nucleotides

The two nucleic acids, DNA and RNA, are polymers of nucleotides. Each nucleotide is composed of a phosphate attached to a ribose or deoxyribose sugar group which is attached to a nitrogenous base. Nucleic acids are critical for the storage and use of genetic information, and its interpretation through the processes of transcription and protein biosynthesis. This information is protected by DNA repair mechanisms and propagated through DNA replication. Many viruses have an RNA genome, such as HIV, which uses reverse transcription to create a DNA template from its viral RNA genome. RNA in ribozymes such as spliceosomes and ribosomes is similar to enzymes as it can catalyze chemical reactions. Individual nucleosides are made by attaching a nucleobase to a ribose sugar. These bases are heterocyclic rings containing nitrogen, classified as purines or pyrimidines. Nucleotides also act as coenzymes in metabolic-group-transfer reactions.

Coenzymes

Structure of the coenzyme acetyl-CoA.The transferable acetyl group is bonded to the sulfur atom at the extreme left.

Metabolism involves a vast array of chemical reactions, but most fall

under a few basic types of reactions that involve the transfer of functional groups of atoms and their bonds within molecules.

This common chemistry allows cells to use a small set of metabolic

intermediates to carry chemical groups between different reactions. These group-transfer intermediates are called coenzymes. Each class of group-transfer reactions is carried out by a particular coenzyme, which is the substrate

for a set of enzymes that produce it, and a set of enzymes that consume

it. These coenzymes are therefore continuously made, consumed and then

recycled.

One central coenzyme is adenosine triphosphate

(ATP), the universal energy currency of cells. This nucleotide is used

to transfer chemical energy between different chemical reactions. There

is only a small amount of ATP in cells, but as it is continuously

regenerated, the human body can use about its own weight in ATP per day. ATP acts as a bridge between catabolism and anabolism.

Catabolism breaks down molecules, and anabolism puts them together.

Catabolic reactions generate ATP, and anabolic reactions consume it. It

also serves as a carrier of phosphate groups in phosphorylation reactions.

A vitamin is an organic compound needed in small quantities that cannot be made in cells. In human nutrition,

most vitamins function as coenzymes after modification; for example,

all water-soluble vitamins are phosphorylated or are coupled to

nucleotides when they are used in cells. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+), a derivative of vitamin B3 (niacin), is an important coenzyme that acts as a hydrogen acceptor. Hundreds of separate types of dehydrogenases remove electrons from their substrates and reduce NAD+ into NADH. This reduced form of the coenzyme is then a substrate for any of the reductases in the cell that need to reduce their substrates. Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide exists in two related forms in the cell, NADH and NADPH. The NAD+/NADH form is more important in catabolic reactions, while NADP+/NADPH is used in anabolic reactions.

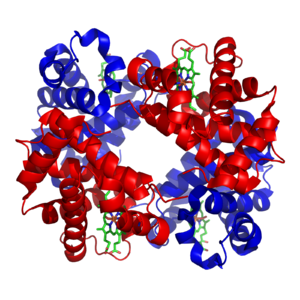

The structure of iron-containing hemoglobin. The protein subunits are in red and blue, and the iron-containing heme groups in green. From PDB: 1GZX.

Minerals and cofactors

Inorganic elements play critical roles in metabolism; some are abundant (e.g. sodium and potassium) while others function at minute concentrations. About 99% of a mammal's mass is made up of the elements carbon, nitrogen, calcium, sodium, chlorine, potassium, hydrogen, phosphorus, oxygen and sulfur. Organic compounds

(proteins, lipids and carbohydrates) contain the majority of the carbon

and nitrogen; most of the oxygen and hydrogen is present as water.

The abundant inorganic elements act as ionic electrolytes. The most important ions are sodium, potassium, calcium, magnesium, chloride, phosphate and the organic ion bicarbonate. The maintenance of precise ion gradients across cell membranes maintains osmotic pressure and pH. Ions are also critical for nerve and muscle function, as action potentials in these tissues are produced by the exchange of electrolytes between the extracellular fluid and the cell's fluid, the cytosol. Electrolytes enter and leave cells through proteins in the cell membrane called ion channels. For example, muscle contraction depends upon the movement of calcium, sodium and potassium through ion channels in the cell membrane and T-tubules.

Transition metals are usually present as trace elements in organisms, with zinc and iron being most abundant of those. These metals are used in some proteins as cofactors and are essential for the activity of enzymes such as catalase and oxygen-carrier proteins such as hemoglobin.

Metal cofactors are bound tightly to specific sites in proteins;

although enzyme cofactors can be modified during catalysis, they always

return to their original state by the end of the reaction catalyzed.

Metal micronutrients are taken up into organisms by specific

transporters and bind to storage proteins such as ferritin or metallothionein when not in use.

Catabolism

Catabolism

is the set of metabolic processes that break down large molecules.

These include breaking down and oxidizing food molecules. The purpose of

the catabolic reactions is to provide the energy and components needed

by anabolic reactions which build molecules. The exact nature of these

catabolic reactions differ from organism to organism, and organisms can

be classified based on their sources of energy and carbon (their primary nutritional groups), as shown in the table below. Organic molecules are used as a source of energy by organotrophs, while lithotrophs use inorganic substrates, and phototrophs capture sunlight as chemical energy. However, all these different forms of metabolism depend on redox reactions that involve the transfer of electrons from reduced donor molecules such as organic molecules, water, ammonia, hydrogen sulfide or ferrous ions to acceptor molecules such as oxygen, nitrate or sulfate. In animals, these reactions involve complex organic molecules that are broken down to simpler molecules, such as carbon dioxide and water. In photosynthetic organisms, such as plants and cyanobacteria, these electron-transfer reactions do not release energy but are used as a way of storing energy absorbed from sunlight.

| Energy source | sunlight | photo- | -troph | ||

| Preformed molecules | chemo- | ||||

| Electron donor | organic compound | organo- | |||

| inorganic compound | litho- | ||||

| Carbon source | organic compound | hetero- | |||

| inorganic compound | auto- | ||||

The most common set of catabolic reactions in animals can be

separated into three main stages. In the first stage, large organic

molecules, such as proteins, polysaccharides or lipids,

are digested into their smaller components outside cells. Next, these

smaller molecules are taken up by cells and converted to smaller

molecules, usually acetyl coenzyme A (acetyl-CoA), which releases some energy. Finally, the acetyl group on the CoA is oxidised to water and carbon dioxide in the citric acid cycle and electron transport chain, releasing the energy that is stored by reducing the coenzyme nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD+) into NADH.

Digestion

Macromolecules such as starch, cellulose or proteins cannot be

rapidly taken up by cells and must be broken into their smaller units

before they can be used in cell metabolism. Several common classes of

enzymes digest these polymers. These digestive enzymes include proteases that digest proteins into amino acids, as well as glycoside hydrolases that digest polysaccharides into simple sugars known as monosaccharides.

Microbes simply secrete digestive enzymes into their surroundings, while animals only secrete these enzymes from specialized cells in their guts, including the stomach and pancreas, and salivary glands. The amino acids or sugars released by these extracellular enzymes are then pumped into cells by active transport proteins.

A simplified outline of the catabolism of proteins, carbohydrates and fats

Energy from organic compounds

Carbohydrate catabolism is the breakdown of carbohydrates into

smaller units. Carbohydrates are usually taken into cells once they have

been digested into monosaccharides. Once inside, the major route of breakdown is glycolysis, where sugars such as glucose and fructose are converted into pyruvate and some ATP is generated. Pyruvate is an intermediate in several metabolic pathways, but the majority is converted to acetyl-CoA through aerobic (with oxygen) glycolysis and fed into the citric acid cycle. Although some more ATP is generated in the citric acid cycle, the most important product is NADH, which is made from NAD+ as the acetyl-CoA is oxidized. This oxidation releases carbon dioxide as a waste product. In anaerobic conditions, glycolysis produces lactate, through the enzyme lactate dehydrogenase re-oxidizing NADH to NAD+ for re-use in glycolysis. An alternative route for glucose breakdown is the pentose phosphate pathway, which reduces the coenzyme NADPH and produces pentose sugars such as ribose, the sugar component of nucleic acids.

Fats are catabolised by hydrolysis to free fatty acids and glycerol. The glycerol enters glycolysis and the fatty acids are broken down by beta oxidation

to release acetyl-CoA, which then is fed into the citric acid cycle.

Fatty acids release more energy upon oxidation than carbohydrates

because carbohydrates contain more oxygen in their structures. Steroids

are also broken down by some bacteria in a process similar to beta

oxidation, and this breakdown process involves the release of

significant amounts of acetyl-CoA, propionyl-CoA, and pyruvate, which

can all be used by the cell for energy. M. tuberculosis can also grow on the lipid cholesterol

as a sole source of carbon, and genes involved in the cholesterol use

pathway(s) have been validated as important during various stages of the

infection lifecycle of M. tuberculosis.

Amino acids are either used to synthesize proteins and other biomolecules, or oxidized to urea and carbon dioxide as a source of energy. The oxidation pathway starts with the removal of the amino group by a transaminase. The amino group is fed into the urea cycle, leaving a deaminated carbon skeleton in the form of a keto acid. Several of these keto acids are intermediates in the citric acid cycle, for example the deamination of glutamate forms α-ketoglutarate. The glucogenic amino acids can also be converted into glucose, through gluconeogenesis (discussed below).

Energy transformations

Oxidative phosphorylation

In oxidative phosphorylation, the electrons removed from organic

molecules in areas such as the protagon acid cycle are transferred to

oxygen and the energy released is used to make ATP. This is done in eukaryotes by a series of proteins in the membranes of mitochondria called the electron transport chain. In prokaryotes, these proteins are found in the cell's inner membrane. These proteins use the energy released from passing electrons from reduced molecules like NADH onto oxygen to pump protons across a membrane.

Mechanism of ATP synthase. ATP is shown in red, ADP and phosphate in pink and the rotating stalk subunit in black.

Pumping protons out of the mitochondria creates a proton concentration difference across the membrane and generates an electrochemical gradient. This force drives protons back into the mitochondrion through the base of an enzyme called ATP synthase. The flow of protons makes the stalk subunit rotate, causing the active site of the synthase domain to change shape and phosphorylate adenosine diphosphate – turning it into ATP.

Energy from inorganic compounds

Chemolithotrophy is a type of metabolism found in prokaryotes where energy is obtained from the oxidation of inorganic compounds. These organisms can use hydrogen, reduced sulfur compounds (such as sulfide, hydrogen sulfide and thiosulfate), ferrous iron (FeII) or ammonia as sources of reducing power and they gain energy from the oxidation of these compounds with electron acceptors such as oxygen or nitrite. These microbial processes are important in global biogeochemical cycles such as acetogenesis, nitrification and denitrification and are critical for soil fertility.

Energy from light

The energy in sunlight is captured by plants, cyanobacteria, purple bacteria, green sulfur bacteria and some protists.

This process is often coupled to the conversion of carbon dioxide into

organic compounds, as part of photosynthesis, which is discussed below.

The energy capture and carbon fixation systems can however operate

separately in prokaryotes, as purple bacteria and green sulfur bacteria

can use sunlight as a source of energy, while switching between carbon

fixation and the fermentation of organic compounds.

In many organisms the capture of solar energy is similar in

principle to oxidative phosphorylation, as it involves the storage of

energy as a proton concentration gradient. This proton motive force then

drives ATP synthesis. The electrons needed to drive this electron transport chain come from light-gathering proteins called photosynthetic reaction centres or rhodopsins. Reaction centers are classed into two types depending on the type of photosynthetic pigment present, with most photosynthetic bacteria only having one type, while plants and cyanobacteria have two.

In plants, algae, and cyanobacteria, photosystem II uses light energy to remove electrons from water, releasing oxygen as a waste product. The electrons then flow to the cytochrome b6f complex, which uses their energy to pump protons across the thylakoid membrane in the chloroplast. These protons move back through the membrane as they drive the ATP synthase, as before. The electrons then flow through photosystem I and can then either be used to reduce the coenzyme NADP+, for use in the Calvin cycle, which is discussed below, or recycled for further ATP generation.

Anabolism

Anabolism is the set of constructive metabolic processes where

the energy released by catabolism is used to synthesize complex

molecules. In general, the complex molecules that make up cellular

structures are constructed step-by-step from small and simple

precursors. Anabolism involves three basic stages. First, the production

of precursors such as amino acids, monosaccharides, isoprenoids and nucleotides,

secondly, their activation into reactive forms using energy from ATP,

and thirdly, the assembly of these precursors into complex molecules

such as proteins, polysaccharides, lipids and nucleic acids.

Organisms differ according to the number of constructed molecules in their cells. Autotrophs

such as plants can construct the complex organic molecules in cells

such as polysaccharides and proteins from simple molecules like carbon dioxide and water. Heterotrophs,

on the other hand, require a source of more complex substances, such as

monosaccharides and amino acids, to produce these complex molecules.

Organisms can be further classified by ultimate source of their energy:

photoautotrophs and photoheterotrophs obtain energy from light, whereas

chemoautotrophs and chemoheterotrophs obtain energy from inorganic

oxidation reactions.

Carbon fixation

Plant cells (bounded by purple walls) filled with chloroplasts (green), which are the site of photosynthesis

Photosynthesis is the synthesis of carbohydrates from sunlight and carbon dioxide (CO2).

In plants, cyanobacteria and algae, oxygenic photosynthesis splits

water, with oxygen produced as a waste product. This process uses the

ATP and NADPH produced by the photosynthetic reaction centres, as described above, to convert CO2 into glycerate 3-phosphate, which can then be converted into glucose. This carbon-fixation reaction is carried out by the enzyme RuBisCO as part of the Calvin – Benson cycle. Three types of photosynthesis occur in plants, C3 carbon fixation, C4 carbon fixation and CAM photosynthesis. These differ by the route that carbon dioxide takes to the Calvin cycle, with C3 plants fixing CO2 directly, while C4 and CAM photosynthesis incorporate the CO2 into other compounds first, as adaptations to deal with intense sunlight and dry conditions.

In photosynthetic prokaryotes the mechanisms of carbon fixation are more diverse. Here, carbon dioxide can be fixed by the Calvin – Benson cycle, a reversed citric acid cycle, or the carboxylation of acetyl-CoA. Prokaryotic chemoautotrophs also fix CO2 through the Calvin – Benson cycle, but use energy from inorganic compounds to drive the reaction.

Carbohydrates and glycans

In carbohydrate anabolism, simple organic acids can be converted into monosaccharides such as glucose and then used to assemble polysaccharides such as starch. The generation of glucose from compounds like pyruvate, lactate, glycerol, glycerate 3-phosphate and amino acids is called gluconeogenesis. Gluconeogenesis converts pyruvate to glucose-6-phosphate through a series of intermediates, many of which are shared with glycolysis. However, this pathway is not simply glycolysis

run in reverse, as several steps are catalyzed by non-glycolytic

enzymes. This is important as it allows the formation and breakdown of

glucose to be regulated separately, and prevents both pathways from

running simultaneously in a futile cycle.

Although fat is a common way of storing energy, in vertebrates such as humans the fatty acids in these stores cannot be converted to glucose through gluconeogenesis as these organisms cannot convert acetyl-CoA into pyruvate; plants do, but animals do not, have the necessary enzymatic machinery. As a result, after long-term starvation, vertebrates need to produce ketone bodies from fatty acids to replace glucose in tissues such as the brain that cannot metabolize fatty acids. In other organisms such as plants and bacteria, this metabolic problem is solved using the glyoxylate cycle, which bypasses the decarboxylation step in the citric acid cycle and allows the transformation of acetyl-CoA to oxaloacetate, where it can be used for the production of glucose.

Polysaccharides and glycans are made by the sequential addition of monosaccharides by glycosyltransferase from a reactive sugar-phosphate donor such as uridine diphosphate glucose (UDP-glucose) to an acceptor hydroxyl group on the growing polysaccharide. As any of the hydroxyl groups on the ring of the substrate can be acceptors, the polysaccharides produced can have straight or branched structures.

The polysaccharides produced can have structural or metabolic functions

themselves, or be transferred to lipids and proteins by enzymes called oligosaccharyltransferases.

Fatty acids, isoprenoids and steroids

Simplified version of the steroid synthesis pathway with the intermediates isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP), dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP), geranyl pyrophosphate (GPP) and squalene shown. Some intermediates are omitted for clarity.

Fatty acids are made by fatty acid synthases

that polymerize and then reduce acetyl-CoA units. The acyl chains in

the fatty acids are extended by a cycle of reactions that add the acyl

group, reduce it to an alcohol, dehydrate it to an alkene group and then reduce it again to an alkane

group. The enzymes of fatty acid biosynthesis are divided into two

groups: in animals and fungi, all these fatty acid synthase reactions

are carried out by a single multifunctional type I protein, while in plant plastids and bacteria separate type II enzymes perform each step in the pathway.

Terpenes and isoprenoids are a large class of lipids that include the carotenoids and form the largest class of plant natural products. These compounds are made by the assembly and modification of isoprene units donated from the reactive precursors isopentenyl pyrophosphate and dimethylallyl pyrophosphate. These precursors can be made in different ways. In animals and archaea, the mevalonate pathway produces these compounds from acetyl-CoA, while in plants and bacteria the non-mevalonate pathway uses pyruvate and glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate as substrates. One important reaction that uses these activated isoprene donors is steroid biosynthesis. Here, the isoprene units are joined together to make squalene and then folded up and formed into a set of rings to make lanosterol. Lanosterol can then be converted into other steroids such as cholesterol and ergosterol.

Proteins

Organisms vary in their ability to synthesize the 20 common amino

acids. Most bacteria and plants can synthesize all twenty, but mammals

can only synthesize eleven nonessential amino acids, so nine essential amino acids must be obtained from food. Some simple parasites, such as the bacteria Mycoplasma pneumoniae, lack all amino acid synthesis and take their amino acids directly from their hosts.

All amino acids are synthesized from intermediates in glycolysis, the

citric acid cycle, or the pentose phosphate pathway. Nitrogen is

provided by glutamate and glutamine. Amino acid synthesis depends on the formation of the appropriate alpha-keto acid, which is then transaminated to form an amino acid.

Amino acids are made into proteins by being joined together in a chain of peptide bonds. Each different protein has a unique sequence of amino acid residues: this is its primary structure.

Just as the letters of the alphabet can be combined to form an almost

endless variety of words, amino acids can be linked in varying sequences

to form a huge variety of proteins. Proteins are made from amino acids

that have been activated by attachment to a transfer RNA molecule through an ester bond. This aminoacyl-tRNA precursor is produced in an ATP-dependent reaction carried out by an aminoacyl tRNA synthetase. This aminoacyl-tRNA is then a substrate for the ribosome, which joins the amino acid onto the elongating protein chain, using the sequence information in a messenger RNA.

Nucleotide synthesis and salvage

Nucleotides are made from amino acids, carbon dioxide and formic acid in pathways that require large amounts of metabolic energy. Consequently, most organisms have efficient systems to salvage preformed nucleotides. Purines are synthesized as nucleosides (bases attached to ribose). Both adenine and guanine are made from the precursor nucleoside inosine monophosphate, which is synthesized using atoms from the amino acids glycine, glutamine, and aspartic acid, as well as formate transferred from the coenzyme tetrahydrofolate. Pyrimidines, on the other hand, are synthesized from the base orotate, which is formed from glutamine and aspartate.

Xenobiotics and redox metabolism

All organisms are constantly exposed to compounds that they cannot

use as foods and would be harmful if they accumulated in cells, as they

have no metabolic function. These potentially damaging compounds are

called xenobiotics. Xenobiotics such as synthetic drugs, natural poisons and antibiotics are detoxified by a set of xenobiotic-metabolizing enzymes. In humans, these include cytochrome P450 oxidases, UDP-glucuronosyltransferases, and glutathione S-transferases.

This system of enzymes acts in three stages to firstly oxidize the

xenobiotic (phase I) and then conjugate water-soluble groups onto the

molecule (phase II). The modified water-soluble xenobiotic can then be

pumped out of cells and in multicellular organisms may be further

metabolized before being excreted (phase III). In ecology, these reactions are particularly important in microbial biodegradation of pollutants and the bioremediation of contaminated land and oil spills.

Many of these microbial reactions are shared with multicellular

organisms, but due to the incredible diversity of types of microbes

these organisms are able to deal with a far wider range of xenobiotics

than multicellular organisms, and can degrade even persistent organic pollutants such as organochloride compounds.

A related problem for aerobic organisms is oxidative stress. Here, processes including oxidative phosphorylation and the formation of disulfide bonds during protein folding produce reactive oxygen species such as hydrogen peroxide. These damaging oxidants are removed by antioxidant metabolites such as glutathione and enzymes such as catalases and peroxidases.

Thermodynamics of living organisms

Living organisms must obey the laws of thermodynamics, which describe the transfer of heat and work. The second law of thermodynamics states that in any closed system, the amount of entropy

(disorder) cannot decrease. Although living organisms' amazing

complexity appears to contradict this law, life is possible as all

organisms are open systems that exchange matter and energy with their surroundings. Thus living systems are not in equilibrium, but instead are dissipative systems that maintain their state of high complexity by causing a larger increase in the entropy of their environments. The metabolism of a cell achieves this by coupling the spontaneous processes of catabolism to the non-spontaneous processes of anabolism. In thermodynamic terms, metabolism maintains order by creating disorder.

Regulation and control

As the environments of most organisms are constantly changing, the reactions of metabolism must be finely regulated to maintain a constant set of conditions within cells, a condition called homeostasis. Metabolic regulation also allows organisms to respond to signals and interact actively with their environments. Two closely linked concepts are important for understanding how metabolic pathways are controlled. Firstly, the regulation of an enzyme in a pathway is how its activity is increased and decreased in response to signals. Secondly, the control exerted by this enzyme is the effect that these changes in its activity have on the overall rate of the pathway (the flux through the pathway). For example, an enzyme may show large changes in activity (i.e.

it is highly regulated) but if these changes have little effect on the

flux of a metabolic pathway, then this enzyme is not involved in the

control of the pathway.

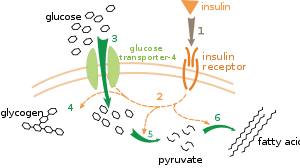

Effect of insulin on glucose uptake and metabolism.

Insulin binds to its receptor (1), which in turn starts many protein

activation cascades (2). These include: translocation of Glut-4

transporter to the plasma membrane and influx of glucose (3), glycogen synthesis (4), glycolysis (5) and fatty acid synthesis (6).

There are multiple levels of metabolic regulation. In intrinsic

regulation, the metabolic pathway self-regulates to respond to changes

in the levels of substrates or products; for example, a decrease in the

amount of product can increase the flux through the pathway to compensate. This type of regulation often involves allosteric regulation of the activities of multiple enzymes in the pathway.

Extrinsic control involves a cell in a multicellular organism changing

its metabolism in response to signals from other cells. These signals

are usually in the form of soluble messengers such as hormones and growth factors and are detected by specific receptors on the cell surface. These signals are then transmitted inside the cell by second messenger systems that often involved the phosphorylation of proteins.

A very well understood example of extrinsic control is the regulation of glucose metabolism by the hormone insulin. Insulin is produced in response to rises in blood glucose levels. Binding of the hormone to insulin receptors on cells then activates a cascade of protein kinases that cause the cells to take up glucose and convert it into storage molecules such as fatty acids and glycogen. The metabolism of glycogen is controlled by activity of phosphorylase, the enzyme that breaks down glycogen, and glycogen synthase,

the enzyme that makes it. These enzymes are regulated in a reciprocal

fashion, with phosphorylation inhibiting glycogen synthase, but

activating phosphorylase. Insulin causes glycogen synthesis by

activating protein phosphatases and producing a decrease in the phosphorylation of these enzymes.

Evolution

Evolutionary tree showing the common ancestry of organisms from all three domains of life. Bacteria are colored blue, eukaryotes red, and archaea green. Relative positions of some of the phyla included are shown around the tree.

The central pathways of metabolism described above, such as glycolysis and the citric acid cycle, are present in all three domains of living things and were present in the last universal common ancestor. This universal ancestral cell was prokaryotic and probably a methanogen that had extensive amino acid, nucleotide, carbohydrate and lipid metabolism. The retention of these ancient pathways during later evolution

may be the result of these reactions having been an optimal solution to

their particular metabolic problems, with pathways such as glycolysis

and the citric acid cycle producing their end products highly

efficiently and in a minimal number of steps. The first pathways of enzyme-based metabolism may have been parts of purine nucleotide metabolism, while previous metabolic pathways were a part of the ancient RNA world.

Many models have been proposed to describe the mechanisms by

which novel metabolic pathways evolve. These include the sequential

addition of novel enzymes to a short ancestral pathway, the duplication

and then divergence of entire pathways as well as the recruitment of

pre-existing enzymes and their assembly into a novel reaction pathway.

The relative importance of these mechanisms is unclear, but genomic

studies have shown that enzymes in a pathway are likely to have a shared

ancestry, suggesting that many pathways have evolved in a step-by-step

fashion with novel functions created from pre-existing steps in the

pathway.

An alternative model comes from studies that trace the evolution of

proteins' structures in metabolic networks, this has suggested that

enzymes are pervasively recruited, borrowing enzymes to perform similar

functions in different metabolic pathways (evident in the MANET database) These recruitment processes result in an evolutionary enzymatic mosaic.

A third possibility is that some parts of metabolism might exist as

"modules" that can be reused in different pathways and perform similar

functions on different molecules.

As well as the evolution of new metabolic pathways, evolution can

also cause the loss of metabolic functions. For example, in some parasites

metabolic processes that are not essential for survival are lost and

preformed amino acids, nucleotides and carbohydrates may instead be

scavenged from the host. Similar reduced metabolic capabilities are seen in endosymbiotic organisms.

Investigation and manipulation

Metabolic network of the Arabidopsis thaliana citric acid cycle. Enzymes and metabolites are shown as red squares and the interactions between them as black lines.

Classically, metabolism is studied by a reductionist approach that focuses on a single metabolic pathway. Particularly valuable is the use of radioactive tracers

at the whole-organism, tissue and cellular levels, which define the

paths from precursors to final products by identifying radioactively

labelled intermediates and products. The enzymes that catalyze these chemical reactions can then be purified and their kinetics and responses to inhibitors

investigated. A parallel approach is to identify the small molecules in

a cell or tissue; the complete set of these molecules is called the metabolome.

Overall, these studies give a good view of the structure and function

of simple metabolic pathways, but are inadequate when applied to more

complex systems such as the metabolism of a complete cell.

An idea of the complexity of the metabolic networks

in cells that contain thousands of different enzymes is given by the

figure showing the interactions between just 43 proteins and 40

metabolites to the right: the sequences of genomes provide lists

containing anything up to 45,000 genes.

However, it is now possible to use this genomic data to reconstruct

complete networks of biochemical reactions and produce more holistic mathematical models that may explain and predict their behavior.

These models are especially powerful when used to integrate the pathway

and metabolite data obtained through classical methods with data on gene expression from proteomic and DNA microarray studies.

Using these techniques, a model of human metabolism has now been

produced, which will guide future drug discovery and biochemical

research. These models are now used in network analysis, to classify human diseases into groups that share common proteins or metabolites.

Bacterial metabolic networks are a striking example of bow-tie

organization, an architecture able to input a wide range of nutrients

and produce a large variety of products and complex macromolecules using

a relatively few intermediate common currencies.

A major technological application of this information is metabolic engineering. Here, organisms such as yeast, plants or bacteria are genetically modified to make them more useful in biotechnology and aid the production of drugs such as antibiotics or industrial chemicals such as 1,3-propanediol and shikimic acid.

These genetic modifications usually aim to reduce the amount of energy

used to produce the product, increase yields and reduce the production

of wastes.

History

The term metabolism is derived from the Greek Μεταβολισμός – "Metabolismos" for "change", or "overthrow".

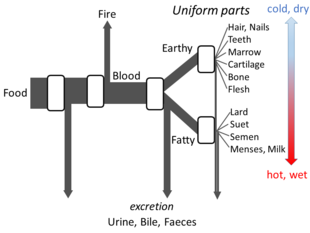

Aristotle's metabolism as an open flow model

Greek philosophy

Aristotle's The Parts of Animals sets out enough details of his views on metabolism

for an open flow model to be made. He believed that at each stage of

the process, materials from food were transformed, with heat being

released as the classical element of fire, and residual materials being excreted as urine, bile, or faeces.

Islamic medicine

Ibn al-Nafis described metabolism in his 1260 AD work titled Al-Risalah al-Kamiliyyah fil Siera al-Nabawiyyah

(The Treatise of Kamil on the Prophet's Biography) which included the

following phrase "Both the body and its parts are in a continuous state

of dissolution and nourishment, so they are inevitably undergoing

permanent change."

Application of the scientific method

The

history of the scientific study of metabolism spans several centuries

and has moved from examining whole animals in early studies, to

examining individual metabolic reactions in modern biochemistry. The

first controlled experiments in human metabolism were published by Santorio Santorio in 1614 in his book Ars de statica medicina. He described how he weighed himself before and after eating, sleep,

working, sex, fasting, drinking, and excreting. He found that most of

the food he took in was lost through what he called "insensible

perspiration".

Santorio Santorio in his steelyard balance, from Ars de statica medicina, first published 1614

In these early studies, the mechanisms of these metabolic processes had not been identified and a vital force was thought to animate living tissue. In the 19th century, when studying the fermentation of sugar to alcohol by yeast, Louis Pasteur

concluded that fermentation was catalyzed by substances within the

yeast cells he called "ferments". He wrote that "alcoholic fermentation

is an act correlated with the life and organization of the yeast cells,

not with the death or putrefaction of the cells." This discovery, along with the publication by Friedrich Wöhler in 1828 of a paper on the chemical synthesis of urea,

and is notable for being the first organic compound prepared from

wholly inorganic precursors. This proved that the organic compounds and

chemical reactions found in cells were no different in principle than

any other part of chemistry.

It was the discovery of enzymes at the beginning of the 20th century by Eduard Buchner

that separated the study of the chemical reactions of metabolism from

the biological study of cells, and marked the beginnings of biochemistry.

The mass of biochemical knowledge grew rapidly throughout the early

20th century. One of the most prolific of these modern biochemists was Hans Krebs who made huge contributions to the study of metabolism. He discovered the urea cycle and later, working with Hans Kornberg, the citric acid cycle and the glyoxylate cycle. Modern biochemical research has been greatly aided by the development of new techniques such as chromatography, X-ray diffraction, NMR spectroscopy, radioisotopic labelling, electron microscopy and molecular dynamics

simulations. These techniques have allowed the discovery and detailed

analysis of the many molecules and metabolic pathways in cells.