|

| |||

|

| |||

| Names | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Preferred IUPAC name

2-Methylbuta-1,3-diene

| |||

| Other names

2-Methyl-1,3-butadiene

Isoprene | |||

| Identifiers | |||

3D model (JSmol)

|

|||

| ChEBI | |||

| ChemSpider | |||

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.001.040 | ||

| KEGG | |||

PubChem CID

|

|||

| UNII | |||

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|||

| Properties | |||

| C5H8 | |||

| Molar mass | 68.12 g/mol | ||

| Density | 0.681 g/cm3 | ||

| Melting point | −143.95 °C (−227.11 °F; 129.20 K) | ||

| Boiling point | 34.067 °C (93.321 °F; 307.217 K) | ||

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |||

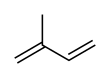

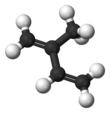

Isoprene, or 2-methyl-1,3-butadiene, is a common organic compound with the formula CH2=C(CH3)−CH=CH2. In its pure form it is a colorless volatile liquid. Isoprene is an unsaturated hydrocarbon. It is produced by many plants and animals (including humans) and its polymers are the main component of natural rubber. C. G. Williams named the compound in 1860 after obtaining it from thermal decomposition (pyrolysis) of natural rubber; he correctly deduced the empirical formula C5H8.

Natural occurrences

Isoprene is produced and emitted by many species of trees (major producers are oaks, poplars, eucalyptus, and some legumes). Yearly production of isoprene emissions by vegetation is around 600 million metric tons, half from tropical broadleaf trees and the remainder primarily from shrubs. This is about equivalent to methane emissions and accounts for around one-third of all hydrocarbons released into the atmosphere.

Plants

Isoprene is made through the methyl-erythritol 4-phosphate pathway (MEP pathway, also called the non-mevalonate pathway) in the chloroplasts of plants. One of the two end products of MEP pathway, dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP), is cleaved by the enzyme isoprene synthase to form isoprene and diphosphate. Therefore, inhibitors that block the MEP pathway, such as fosmidomycin,

also block isoprene formation. Isoprene emission increases dramatically

with temperature and maximizes at around 40 °C. This has led to the

hypothesis that isoprene may protect plants against heat stress

(thermotolerance hypothesis, see below). Emission of isoprene is also

observed in some bacteria and this is thought to come from non-enzymatic

degradations from DMAPP.

Regulation

Isoprene emission in plants is controlled both by the availability of the substrate (DMAPP) and by enzyme (isoprene synthase) activity. In particular, light, CO2 and O2

dependencies of isoprene emission are controlled by substrate

availability, whereas temperature dependency of isoprene emission is

regulated both by substrate level and enzyme activity.

Other organisms

Isoprene is the most abundant hydrocarbon measurable in the breath of humans.[5][6] The estimated production rate of isoprene in the human body is 0.15 µmol/(kg·h),

equivalent to approximately 17 mg/day for a person weighing 70 kg.

Isoprene is common in low concentrations in many foods.

Chemical structure of cis-polyisoprene, the main constituent of natural rubber

Biological roles

Isoprene emission appears to be a mechanism that trees use to combat abiotic stresses.

In particular, isoprene has been shown to protect against moderate heat

stress (around 40 °C). It may also protect plants against large

fluctuations in leaf temperature. Isoprene is incorporated into and

helps stabilize cell membranes in response to heat stress.

Isoprene also confers resistance to reactive oxygen species.

The amount of isoprene released from isoprene-emitting vegetation

depends on leaf mass, leaf area, light (particularly photosynthetic

photon flux density, or PPFD) and leaf temperature. Thus, during the

night, little isoprene is emitted from tree leaves, whereas daytime

emissions are expected to be substantial during hot and sunny days, up

to 25 μg/(g dry-leaf-weight)/hour in many oak species.

Isoprenoids

The isoprene skeleton can be found in naturally occurring compounds called terpenes

(also known as isoprenoids), but these compounds do not arise from

isoprene itself. Instead, the precursor to isoprene units in biological

systems is dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP) and its isomer isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP). The plural 'isoprenes' is sometimes used to refer to terpenes in general.

Examples of isoprenoids include carotene, phytol, retinol (vitamin A), tocopherol (vitamin E), dolichols, and squalene. Heme A has an isoprenoid tail, and lanosterol, the sterol precursor in animals, is derived from squalene and hence from isoprene. The functional isoprene units in biological systems are dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP) and its isomer isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP), which are used in the biosynthesis of naturally occurring isoprenoids such as carotenoids, quinones, lanosterol derivatives (e.g. steroids) and the prenyl chains of certain compounds (e.g. phytol chain of chlorophyll). Isoprenes are used in the cell membrane monolayer of many Archaea,

filling the space between the diglycerol tetraether head groups. This

is thought to add structural resistance to harsh environments in which

many Archaea are found.

Similarly, natural rubber is composed of linear polyisoprene chains of very high molecular weight and other natural molecules.

Simplified version of the steroid synthesis pathway with the intermediates isopentenyl pyrophosphate (IPP), dimethylallyl pyrophosphate (DMAPP), geranyl pyrophosphate (GPP) and squalene shown. Some intermediates are omitted.

Impact on aerosols

After release, isoprene is converted by short-lived free radicals (like the hydroxyl radical) and to a lesser extent by ozone into various species, such as aldehydes, hydroperoxides, organic nitrates, and epoxides, which mix into water droplets and help create aerosols and haze.

While most experts acknowledge that isoprene emission affects

aerosol formation, whether isoprene increases or decreases aerosol

formation is debated. A second major effect of isoprene on the

atmosphere is that in the presence of nitric oxides (NOx) it contributes to the formation of tropospheric (lower atmosphere) ozone,

which is one of the leading air pollutants in many countries. Isoprene

itself is not normally regarded as a pollutant, as it is a natural plant

product. Formation of tropospheric ozone is only possible in presence

of high levels of NOx, which comes almost exclusively from

industrial activities. Isoprene can have the opposite effect and quench

ozone formation under low levels of NOx.

Industrial production

Isoprene is most readily available industrially as a byproduct of the thermal cracking of naphtha or oil, as a side product in the production of ethylene. About 800,000 metric tons are produced annually. About 95% of isoprene production is used to produce cis-1,4-polyisoprene—a synthetic version of natural rubber.

Natural rubber

consists mainly of poly-cis-isoprene with a molecular mass of 100,000

to 1,000,000 g/mol. Typically natural rubber contains a few percent of

other materials, such as proteins, fatty acids, resins, and inorganic

materials. Some natural rubber sources, called gutta percha, are composed of trans-1,4-polyisoprene, a structural isomer that has similar, but not identical, properties.