| |

| |

| Clinical data | |

|---|---|

| Trade names | Neurontin, others |

| Other names | CI-945; GOE-3450; DM-1796 (Gralise) |

| AHFS/Drugs.com | Monograph |

| MedlinePlus | a694007 |

| License data |

|

| Pregnancy category | |

| Routes of administration | By mouth |

| Drug class | Gabapentinoid and GABA analogue |

| ATC code | |

| Legal status | |

| Legal status | |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 27–60% (inversely proportional to dose; a high fat meal also increases bioavailability) |

| Protein binding | Less than 3% |

| Metabolism | Not significantly metabolized |

| Elimination half-life | 5 to 7 hours |

| Excretion | Renal |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS Number | |

| PubChem CID | |

| IUPHAR/BPS | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| UNII | |

| KEGG | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| PDB ligand | |

| CompTox Dashboard (EPA) | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.056.415 |

| Chemical and physical data | |

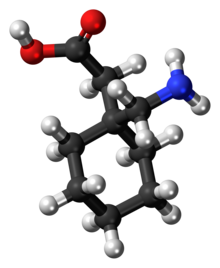

| Formula | C9H17NO2 |

| Molar mass | 171.240 g·mol−1 |

| 3D model (JSmol) | |

Gabapentin, sold under the brand name Neurontin among others, is an anticonvulsant medication used to treat partial seizures, neuropathic pain, hot flashes, and restless legs syndrome. It is recommended as one of a number of first-line medications for the treatment of neuropathic pain caused by diabetic neuropathy, postherpetic neuralgia, and central neuropathic pain. About 15% of those given gabapentin for diabetic neuropathy or postherpetic neuralgia have a measurable benefit. Gabapentin is taken by mouth.

Common side effects include sleepiness and dizziness. Serious side effects include an increased risk of suicide, aggressive behavior, and drug reactions. It is unclear if it is safe during pregnancy or breastfeeding. Lower doses are recommended in those with kidney disease associated with a low kidney function. Gabapentin is a gabapentinoid. It has a molecular structure similar to that of the neurotransmitter γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) and acts by inhibiting certain calcium channels.

Gabapentin was first approved for use in 1993. It has been available as a generic medication in the United States since 2004. The wholesale price in the developing world as of 2015 was about US$10.80 per month; in the United States, it was US$100 to US$200. In 2016, it was the 11th most prescribed medication in the United States, with more than 44 million prescriptions. During the 1990s, Parke-Davis, a subsidiary of Pfizer, began using a number of illegal techniques to encourage physicians in the United States to use gabapentin for unapproved uses. They have paid out millions of dollars to settle lawsuits regarding these activities.

Medical uses

Gabapentin is approved in the United States to treat seizures and neuropathic pain. It is primarily administered by mouth, with a study showing that "rectal administration is not satisfactory". It is also commonly prescribed for many off-label uses, such as treatment of anxiety disorders, insomnia, and bipolar disorder. About 90% of usage is for off-label conditions.

There are, however, concerns regarding the quality of the trials

conducted and evidence for some such uses, especially in the case of its

use as a mood stabilizer in bipolar disorder.

Seizures

Gabapentin is approved for treatment of focal seizures and mixed seizures. There is insufficient evidence for its use in generalized epilepsy.

Neuropathic pain

A 2018 review found that gabapentin was of no benefit in sciatica nor low back pain.

A 2010 European Federation of Neurological Societies task force clinical guideline recommended gabapentin as a first-line treatment for diabetic neuropathy, postherpetic neuralgia, or central pain. It found good evidence that a combination of gabapentin and morphine or oxycodone or nortriptyline worked better than either drug alone; the combination of gabapentin and venlafaxine may be better than gabapentin alone.

A 2017 Cochrane

review found evidence of moderate quality showing a reduction in pain

by 50% in about 15% of people with postherpetic neuralgia and diabetic

neuropathy. Evidence finds little benefit and significant risk in those with chronic low back pain.

It is not known if gabapentin can be used to treat other pain

conditions, and no difference among various formulations or doses of

gabapentin was found.

A 2010 review found that it may be helpful in neuropathic pain due to cancer. It is not effective in HIV-associated sensory neuropathy and does not appear to provide benefit for complex regional pain syndrome.

A 2009 review found gabapentin may reduce opioid use following surgery, but does not help with post-surgery chronic pain. A 2016 review found it does not help with pain following a knee replacement.

It appears to be as effective as pregabalin for neuropathic pain and costs less. All doses appear to result in similar pain relief.

Migraine

The

American Headache Society (AHS) and American Academy of Neurology (AAN)

guidelines classify gabapentin as a drug with "insufficient data to

support or refute use for migraine prophylaxis". A 2013 Cochrane review concluded that gabapentin was not useful for the prevention of episodic migraine in adults.

Anxiety disorders

Gabapentin

has been used off-label for the treatment of anxiety disorders.

However, there is dispute over whether evidence is sufficient to support

it being routinely prescribed for this purpose. While pregabalin may have efficacy in the treatment of refractory anxiety in people with chronic pain, it is unclear if gabapentin is equally effective.

Other uses

Gabapentin

may be useful in the treatment of comorbid anxiety in bipolar patients;

however, it is not effective as a mood-stabilizing treatment for manic

or depressive episodes themselves. Other psychiatric conditions, such as borderline personality disorder, have also been treated off-label with gabapentin. There is insufficient evidence to support its use in obsessive–compulsive disorder and treatment-resistant depression.

Gabapentin may be effective in acquired pendular nystagmus and infantile nystagmus (but not periodic alternating nystagmus). It is effective for treating hot flashes. It may be effective in reducing pain and spasticity in multiple sclerosis.

Gabapentin may reduce symptoms of alcohol withdrawal (but it does not prevent the associated seizures), alcohol dependence and craving.

There is some evidence for its role in the treatment of alcohol use

disorder; the 2015 VA/DoD guideline on substance use disorders lists

gabapentin as a "weak for" and is recommended as a second-line agent. Use for smoking cessation has had mixed results. There is insufficient evidence for its use in cannabis dependence.

Gabapentin is effective in alleviating itching in kidney failure (uremic pruritus) and itching of other causes. It is an established treatment of restless legs syndrome.

Gabapentin may help sleeping problems in people with restless legs

syndrome and partial seizures due to its increase in slow-wave sleep and

augmentation of sleep efficiency. Gabapentin may be an option in essential or orthostatic tremor. Evidence does not support the use of gabapentin in tinnitus.

Side effects

The most common side effects of gabapentin include dizziness, fatigue, drowsiness, ataxia, peripheral edema (swelling of extremities), nystagmus, and tremor. Gabapentin may also produce sexual dysfunction in some patients, symptoms of which may include loss of libido, inability to reach orgasm, and erectile dysfunction. Gabapentin should be used carefully in people with kidney problems due to possible accumulation and toxicity.

Some have suggested avoiding gabapentin in people with a history of myoclonus or myasthenia gravis, as it may induce or mimic the symptoms of these two conditions.

Suicide

In 2009, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration

(FDA) issued a warning of an increased risk of suicidal thoughts and

behaviors in patients taking some anticonvulsant drugs, including

gabapentin, modifying the packaging inserts to reflect this. A 2010 meta-analysis supported the increased risk of suicide associated with gabapentin use.

Studies have also shown an almost doubled rate of suicidal ideation in patients with bipolar disorder who are taking gabapentin versus those taking lithium.

Cancer

An increase in formation of adenocarcinomas

was observed in rats during preclinical trials; however, the clinical

significance of these results remains undetermined. Gabapentin is also

known to induce pancreatic acinar cell carcinomas

in rats through an unknown mechanism, perhaps by stimulation of DNA

synthesis; these tumors did not affect the lifespan of the rats and did

not metastasize.

Abuse and addiction

Surveys

suggest that approximately 1.1 percent of the general population and 22

percent of those attending addiction facilities have a history of abuse

of gabapentin.

Effective 1 July 2017, Kentucky classified gabapentin as a schedule V controlled substance statewide. Effective 9 January 2019, Michigan also classified gabapentin as a schedule V controlled substance. Effective April 2019, the United Kingdom reclassified the drug as a class C controlled substances.

While the mechanisms behind its abuse potential are not well

understood, gabapentin misuse has been recorded across a range of doses,

including those that are considered therapeutic.

Abuse often coincides with other substance use disorders, most commonly

opioids. Mechanistically, the GABAmimetic properties of gabapentin can

induce a euphoria that augments the effects of the opioid being used, as

well aiding in the cessation of commonly experienced opioid-withdrawal

symptoms, such as anxiety.

Misuse of this drug have been recorded for a number of reasons, including self-medication, self-harm and recreational use. Withdrawal symptoms, often resembling those of benzodiazepine withdrawal, play a role in the physical dependence some users experience.

Withdrawal syndrome

Tolerance and withdrawal

symptoms are a common occurrence in prescribed therapeutic users as

well as non-medical recreational users. Withdrawal symptoms typically

emerge within 12 hours to 7 days after stopping gabapentin.

Some of the most commonly reported withdrawal symptoms include

agitation, confusion, disorientation, upset stomach and sweating.

In some cases, users experienced delirium and withdrawal seizures,

which may only respond to the re-administration of gabapentin.

Breathing

In

December 2019, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) warned about

serious breathing issues for those taking gabapentin or pregabalin when used with CNS depressants or for those with lung problems.

The FDA required new warnings about the risk of respiratory

depression to be added to the prescribing information of the

gabapentinoids.

The FDA also required the drug manufacturers to conduct clinical trials

to further evaluate their abuse potential, particularly in combination

with opioids, because misuse and abuse of these products together is

increasing, and co-use may increase the risk of respiratory depression.

Among 49 case reports submitted to the FDA over the five-year

period from 2012 to 2017, twelve people died from respiratory depression

with gabapentinoids, all of whom had at least one risk factor.

The FDA reviewed the results of two randomized, double-blind,

placebo-controlled clinical trials in healthy people, three

observational studies, and several studies in animals. One trial showed that using pregabalin alone and using it with an opioid pain reliever can depress breathing function. The other trial showed gabapentin alone increased pauses in breathing during sleep.

The three observational studies at one academic medical center showed a

relationship between gabapentinoids given before surgery and

respiratory depression occurring after different kinds of surgeries.

The FDA also reviewed several animal studies that showed pregabalin

alone and pregabalin plus opioids can depress respiratory function.

Overdose

Through

excessive ingestion, accidental or otherwise, persons may experience

overdose symptoms including drowsiness, sedation, blurred vision,

slurred speech, somnolence, uncontrollable jerking motions, anxiety and

possibly death, if a very high amount was taken, particularly if

combined with alcohol. For overdose considerations, serum gabapentin

concentrations may be measured for confirmation.

Pharmacology

Pharmacodynamics

Gabapentin is a gabapentinoid, or a ligand of the auxiliary α2δ subunit site of certain voltage-dependent calcium channels (VDCCs), and thereby acts as an inhibitor of α2δ subunit-containing VDCCs. There are two drug-binding α2δ subunits, α2δ-1 and α2δ-2, and gabapentin shows similar affinity for (and hence lack of selectivity between) these two sites. Gabapentin is selective in its binding to the α2δ VDCC subunit. Despite the fact that gabapentin is a GABA analogue, and in spite of its name, it does not bind to the GABA receptors, does not convert into GABA or another GABA receptor agonist in vivo, and does not modulate GABA transport or metabolism. There is currently no evidence that the effects of gabapentin are mediated by any mechanism other than inhibition of α2δ-containing VDCCs. In accordance, inhibition of α2δ-1-containing VDCCs by gabapentin appears to be responsible for its anticonvulsant, analgesic, and anxiolytic effects.

The endogenous α-amino acids L-leucine and L-isoleucine, which closely resemble gabapentin and the other gabapentinoids in chemical structure, are apparent ligands of the α2δ VDCC subunit with similar affinity as the gabapentinoids (e.g., IC50 = 71 nM for L-isoleucine), and are present in human cerebrospinal fluid at micromolar concentrations (e.g., 12.9 μM for L-leucine, 4.8 μM for L-isoleucine). It has been theorized that they may be the endogenous ligands of the subunit and that they may competitively antagonize the effects of gabapentinoids. In accordance, while gabapentinoids like gabapentin and pregabalin have nanomolar affinities for the α2δ subunit, their potencies in vivo are in the low micromolar range, and competition for binding by endogenous L-amino acids has been said to likely be responsible for this discrepancy.

Pharmacokinetics

Absorption

Gabapentin is absorbed from the intestines by an active transport process mediated via the large neutral amino acid transporter 1 (LAT1, SLC7A5), a transporter for amino acids such as L-leucine and L-phenylalanine. Very few (less than 10 drugs) are known to be transported by this transporter. Gabapentin is transported solely by the LAT1, and the LAT1 is easily saturable, so the pharmacokinetics of gabapentin are dose-dependent, with diminished bioavailability and delayed peak levels at higher doses. Gabapentin enacarbil is transported not by the LAT1 but by the monocarboxylate transporter 1 (MCT1) and the sodium-dependent multivitamin transporter (SMVT), and no saturation of bioavailability has been observed with the drug up to a dose of 2,800 mg.

The oral bioavailability

of gabapentin is approximately 80% at 100 mg administered three times

daily once every 8 hours, but decreases to 60% at 300 mg, 47% at 400 mg,

34% at 800 mg, 33% at 1,200 mg, and 27% at 1,600 mg, all with the same

dosing schedule. Food increases the area-under-curve levels of gabapentin by about 10%. Drugs that increase the transit time of gabapentin in the small intestine can increase its oral bioavailability; when gabapentin was co-administered with oral morphine (which slows intestinal peristalsis), the oral bioavailability of a 600 mg dose of gabapentin increased by 50%.

The oral bioavailability of gabapentin enacarbil (as gabapentin) is

greater than or equal to 68%, across all doses assessed (up to

2,800 mg), with a mean of approximately 75%.

Gabapentin at a low dose of 100 mg has a Tmax (time to peak levels) of approximately 1.7 hours, while the Tmax increases to 3 to 4 hours at higher doses. Food does not significantly affect the Tmax of gabapentin and increases the Cmax of gabapentin by approximately 10%. The Tmax of the instant-release

(IR) formulation of gabapentin enacarbil (as active gabapentin) is

about 2.1 to 2.6 hours across all doses (350–2,800 mg) with single

administration and 1.6 to 1.9 hours across all doses (350–2,100 mg) with

repeated administration. Conversely, the Tmax of the extended-release

(XR) formulation of gabapentin enacarbil is about 5.1 hours at a single

dose of 1,200 mg in a fasted state and 8.4 hours at a single dose of

1,200 mg in a fed state.

Distribution

Gabapentin crosses the blood–brain barrier and enters the central nervous system. However, due to its low lipophilicity, gabapentin requires active transport across the blood–brain barrier. The LAT1 is highly expressed at the blood–brain barrier and transports gabapentin across into the brain.

As with intestinal absorption of gabapentin mediated by LAT1,

transportation of gabapentin across the blood–brain barrier by LAT1 is

saturable. It does not bind to other drug transporters such as P-glycoprotein (ABCB1) or OCTN2 (SLC22A5). Gabapentin is not significantly bound to plasma proteins (<1 p="">

Metabolism

Gabapentin undergoes little or no metabolism. Conversely, gabapentin enacarbil, which acts as a prodrug of gabapentin, must undergo enzymatic hydrolysis to become active. This is done via non-specific esterases in the intestines and to a lesser extent in the liver.

Elimination

Gabapentin is eliminated renally in the urine. It has a relatively short elimination half-life, with a reported value of 5.0 to 7.0 hours. Similarly, the terminal half-life of gabapentin enacarbil IR (as active gabapentin) is short at approximately 4.5 to 6.5 hours.

The elimination half-life of gabapentin has been found to be extended

with increasing doses; in one series of studies, it was 5.4 hours for

200 mg, 6.7 hours for 400 mg, 7.3 hours for 800 mg, 9.3 hours for

1,200 mg, and 8.3 hours for 1,400 mg, all given in single doses.

Because of its short elimination half-life, gabapentin must be

administered 3 to 4 times per day to maintain therapeutic levels. Conversely, gabapentin enacarbil is taken twice a day and gabapentin XR (brand name Gralise) is taken once a day.

Chemistry

Chemical structures of GABA, gabapentin, and two other gabapentinoids, pregabalin and phenibut.

Gabapentin was designed by researchers at Parke-Davis to be an analogue of the neurotransmitter GABA that could more easily cross the blood–brain barrier. It is a 3-substituted derivative of GABA; hence, it is a GABA analogue, as well as a γ-amino acid. Specifically, gabapentin is a derivative of GABA with a cyclohexane ring at the 3 position (or, somewhat inappropriately named, 3-cyclohexyl-GABA). Gabapentin also closely resembles the α-amino acids L-leucine and L-isoleucine, and this may be of greater relevance in relation to its pharmacodynamics than its structural similarity to GABA. In accordance, the amine and carboxylic acid groups are not in the same orientation as they are in the GABA, and they are more conformationally constrained.

Synthesis

A chemical synthesis of gabapentin has been described.

History

Gabapentin was developed at Parke-Davis and was first described in 1975. Under the brand name Neurontin, it was first approved in May 1993, for the treatment of epilepsy in the United Kingdom, and was marketed in the United States in 1994. Subsequently, gabapentin was approved in the United States for the treatment of postherpetic neuralgia in May 2002. A generic version of gabapentin first became available in the United States in 2004.

An extended-release formulation of gabapentin for once-daily

administration, under the brand name Gralise, was approved in the United

States for the treatment postherpetic neuralgia in January 2011.

Gabapentin enacarbil was introduced in the United States for the

treatment of restless legs syndrome in 2011, and was approved for the

treatment of postherpetic neuralgia in 2012.

Society and culture

Sales

Gabapentin is best known under the brand name Neurontin manufactured by Pfizer subsidiary Parke-Davis. A Pfizer subsidiary named Greenstone markets generic gabapentin.

In December 2004, the FDA granted final approval to a generic equivalent to Neurontin made by the Israeli firm Teva Pharmaceutical Industries (Teva).

Neurontin began as one of Pfizer's best selling drugs; however,

Pfizer was criticized and under litigation for its marketing of the drug

(see Franklin v. Parke-Davis).

Pfizer faced allegations that Parke-Davis marketed the drug for at

least a dozen off-label uses that the FDA had not approved. It has been used as a mainstay drug for migraines, even though it was not approved for such use in 2004.

FDA approval

Gabapentin

was originally approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)

in December 1993, for use as an adjuvant (effective when added to other

antiseizure drugs) medication to control partial seizures in adults; that indication was extended to children in 2000. In 2004, its use for treating postherpetic neuralgia (neuropathic pain following shingles) was approved.

Off-label promotion

Although

some small, non-controlled studies in the 1990s—mostly sponsored by

gabapentin's manufacturer—suggested that treatment for bipolar disorder

with gabapentin may be promising, the preponderance of evidence suggests that it is not effective.

Subsequent to the corporate acquisition of the original patent holder,

the pharmaceutical company Pfizer admitted that there had been

violations of FDA guidelines regarding the promotion of unproven

off-label uses for gabapentin in the Franklin v. Parke-Davis case.

Reuters

reported on 25 March 2010, that "Pfizer Inc violated federal

racketeering law by improperly promoting the epilepsy drug Neurontin ...

Under federal RICO law the penalty is automatically tripled, so the

finding will cost Pfizer $141 million."

The case stems from a claim from Kaiser Foundation Health Plan Inc.

that "it was misled into believing Neurontin was effective for off-label

treatment of migraines, bipolar disorder and other conditions. Pfizer

argued that Kaiser physicians still recommend the drug for those uses."

Bloomberg News

reported "during the trial, Pfizer argued that Kaiser doctors continued

to prescribe the drug even after the health insurer sued Pfizer in

2005. The insurer's website also still lists Neurontin as a drug for

neuropathic pain, Pfizer lawyers said in closing argument."

The Wall Street Journal

noted that Pfizer spokesman Christopher Loder said, "We are

disappointed with the verdict and will pursue post-trial motions and an

appeal." He later added that "the verdict and the judge's rulings are not consistent with the facts and the law."

Franklin v. Parke-Davis case

According to the San Francisco Chronicle, off-label prescriptions accounted for roughly 90 percent of Neurontin sales.

While off-label prescriptions are common for a number of drugs, marketing of off-label uses of a drug is not. In 2004, Warner-Lambert

(which subsequently was acquired by Pfizer) agreed to plead guilty for

activities of its Parke-Davis subsidiary, and to pay $430 million in

fines to settle civil and criminal charges regarding the marketing of

Neurontin for off-label purposes. The 2004 settlement was one of the largest in U.S. history, and the first off-label promotion case brought successfully under the False Claims Act.

Brand names

Gabapentin

was originally marketed under the brand name Neurontin. Since it became

generic, it has been marketed worldwide using over 300 different brand

names. An extended-release

formulation of gabapentin for once-daily administration was introduced

in 2011 for postherpetic neuralgia under the brand name Gralise.

A capsule of gabapentin.

Related drugs

Parke-Davis developed a drug called pregabalin as a successor to gabapentin. Pregabalin was brought to market by Pfizer as Lyrica after the company acquired Warner-Lambert. Pregabalin is related in structure to gabapentin. Another new drug atagabalin has been trialed by Pfizer as a treatment for insomnia.

A prodrug form (gabapentin enacarbil) was approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2011 under the brand name Horizant for the treatment of moderate-to-severe restless legs syndrome (RLS) and in 2012 for postherpetic neuralgia in adults. In Canada, it has completed Phase 3 trials for RLS (September 2019). It was designed for increased oral bioavailability over gabapentin.

Recreational use

Also known on the streets as "Gabbies", gabapentin is increasingly being abused and misused for its euphoric effects.

Furthermore, its misuse predominantly coincides with the usage of other

illicit drugs, namely opioids, benzodiazepines, and alcohol.

After Kentucky's implementation of stricter legislation regarding

opioid prescriptions in 2012, there was an increase in gabapentin-only

and multi-drug use in 2012–2015. The majority of these cases were from

overdose in suspected suicide attempts. These rates were also

accompanied by increases in abuse and recreational use.

Gabapentin misuse, toxicity, and use in suicide attempts among adults in the US increased from 2013 to 2017.

Veterinary use

In cats, gabapentin can be used as an analgesic in multi-modal pain management. It is also used as an anxiety medication to reduce stress in cats for travel or vet visits.

Gabapentin is also used in dogs and other animals, but some

formulations (especially liquid forms) meant for human use contain the

sweetener xylitol, which is toxic to dogs.