The history of coal mining in the United States goes back to the 1300s, when the Hopi Indians used coal. The first commercial use came in 1701, within the Manakin-Sabot area of Richmond, Virginia. Coal was the dominant power source in the United States in the late 1800s and early 1900s, and although in rapid decline it remains a significant source of energy in 2019.

Coal became the largest source of energy in the 1880s, when it overtook wood, and remained the largest source until the early 1950s, when coal was exceeded by petroleum. Coal provided more than half of the nation's energy from the 1880s to the 1940s, and from 1906 to 1920 provided more than three-quarters of US energy.

19th century

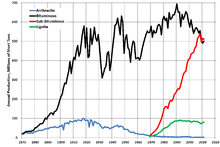

At the start of the 19th century, coal mining was almost all bituminous coal. In 1810, 176,000 short tons of bituminous coal, and 2,000 tons of anthracite coal, were mined in the United States. American coal mining grew rapidly in the early 1820s, doubling or tripling every decade. Anthracite mining overtook bituminous coal mining in the 1840s; from 1843 through 1868, more anthracite was mined than bituminous coal. But the more limited deposits of anthracite could not satisfy the increasing demand for coal; from 1869, bituminous coal was the dominant grade of coal mined. Another reason for the decline in anthracite was the decline in its use in iron smelting, where it was displaced by coke in blast furnaces after the Civil War. Coke stayed hard and porous and was able to support the heavy column of ore and fuel in the large blast furnaces it enabled.

Anthracite (or "hard" coal) exploitation began before the War of 1812 spurred by the interest and opportunism of the Wurt brothers of Philadelphia. Burning clean and smokeless, anthracite became the preferred fuel in cities, replacing wood by about 1850, the same pattern seen in Europe. The East became deforested, driving up price of fuel wood. Anthracite from the Northeastern Pennsylvania Coal Region and later from West Virginia was valued for household use because it burns cleanly with little ash. It was also used in the early foundries of Philadelphia, New York, Newark and Allentown. The rich Pennsylvania anthracite fields were close to the big eastern cities, and nearly every major railroad in the Eastern United States such as the Reading Railroad, Lehigh & Erie, Central Railroad of New Jersey, Pennsylvania Railroad and Delaware and Hudson Railroad, extended lines into the anthracite fields. Many railroads began as mining company shortline railroads. By 1840, annual hard coal output had passed the million-short ton mark, and then quadrupled by 1850, and as it grew it pushed railroad construction, mining and steel production in a synergistic symbiosis.

In the mid-century Pittsburgh was the principal market. After 1850, soft coal, which is cheaper but dirtier, came into demand for railway locomotives and stationary steam engines, and was used to make coke for steel after 1870.

20th century

Total coal output soared until 1918; before 1890, it doubled every ten years, going from 8.4 million short tons in 1850 to 40 million in 1870, 270 million in 1900, and peaking at 680 million short tons in 1918. New soft coal fields opened in Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, as well as West Virginia, Kentucky and Alabama. The Great Depression of the 1930s lowered the demand to 360 million short tons in 1932.

Mining history by state

Pennsylvania

- The first anthracite coal was mined in 1768 by Obadiah Gore, a blacksmith, in the Wyoming Valley (Kingston, PA). This was in the very early days of colonists settling in Northeastern Pennsylvania from Connecticut. The Susquehanna Company was an expedition that came into the Wyoming Valley and established the first 5 towns: Pittston, Plymouth, Wilkes-Barre, Nanticoke (later Hanover), and Forty Fort (later Kingston).

- Nicholas Scull, a famous colonial surveyor issued a map in Philadelphia in 1770 that showed the location of 5 coal mines all in Schuylkill County: York Farm (Pottsville), near Silverton Junction, near Llewellyn, and 2 more around Ashland.

- By 1807, fifty tons of coal was being sold by the Smith Brothers out of Plymouth, Pennsylvania. They exported it via barge on the Susquehanna River to Columbia, PA (Lancaster County).

- In February 1808, Wilkes-Barre resident, Jesse Fell, experimented with a successful open-air grate that kept anthracite burning in low-yield household fires. The Smiths seized on Fell's discovery and returned to Columbia with more coal and instructions for local blacksmiths on preparing the grates.

- Bituminous coal was first mined in Pennsylvania at "Coal Hill" (Mount Washington), just across the Monongahela River from the city of Pittsburgh. The coal was extracted from drift mines in the Pittsburgh coal seam, which outcrops along the hillside and transported by canoe to the nearby military garrison. By 1830, the city of Pittsburgh consumed more than 400 tons per day of bituminous coal for domestic and light industrial use.

The Lackawanna Valley in Pennsylvania was rich in anthracite coal and iron deposits. Brothers George W. Scranton and Seldon T. Scranton moved to the valley in 1840 and settled in the five-house town of Slocum's Hollow (now Scranton) to establish an iron forge. The Scrantons succeeded by using a technological innovation in iron smelting, the "hot blast", developed in Scotland in 1828. The Scrantons also used anthracite coal to make steel, rather than existing methods which used charcoal or bituminous coal.

West Virginia

In 1883, thousands of European immigrants and a large number of African Americans migrated to southern West Virginia to work in coal mines. These coal miners worked in company mines with company tools and equipment, which they were required to lease. Along with these expenses, the miners were deducted pay for housing rent and items they purchased from company stores. Many coal companies paid miners with company scrip (private money), good only at company-owned stores.

In addition to the poor economic condition, safety in the mines was a great concern. West Virginia fell behind other states in regulating mining conditions, and between 1890 and 1912, had a higher mine death rate than any other state. West Virginia was the site of the worst coal mining disaster to date, the Monongah Mining disaster of Monongah, West Virginia in 1907. The disaster was caused by the ignition of methane gas (also called "firedamp"), which in turn ignited the coal dust, killing 362 men. The disaster impelled the United States Congress to create the Bureau of Mines.

Kentucky

Diana Baldwin and Anita Cherry are believed to have been the first women to work inside an American coal mine, and were the first women to work inside a mine who were members of the United Mine Workers of America. They began that work in 1973 in Jenkins, Kentucky.

This section needs expansion, with information about coal mining in eastern Kentucky.

Employment

Coal-mining employment increased rapidly in the late 1800s and early 1900s, and peaked in 1923 at 798,000. Since then, the number of miners has fallen considerably since, due to mechanization. By 2019 it had fallen below 55,000.

Accidents

The rate of coal-mining fatalities has been declining since the early 1900s, both in the raw number of fatalities, and in the fatality rate per miner.

United Mine Workers union

| Coal Producing States, 1889 | |

|---|---|

| State | Coal Production (thousands of short tons) |

| Pennsylvania | 81,719 |

| Illinois | 12,104 |

| Ohio | 9,977 |

| West Virginia | 6,232 |

| Iowa | 4,095 |

| Alabama | 3,573 |

| Indiana | 2,845 |

| Colorado | 2,544 |

| Kentucky | 2,400 |

| Kansas | 2,221 |

| Tennessee | 1,926 |

Since it was founded in 1890, the United Mine Workers (UMW) labor union has played a key role in United States coal mining.

Some notable labor strikes and events include:

- Bituminous Coal Miners' Strike of 1894

- Lattimer Massacre, 1897

- Battle of Virden, 1898

- Coal Strike of 1902

- Ludlow massacre, 1914

- Herrin Massacre, 1921

Under John L. Lewis, the United Mine Workers became the dominant force in the coal fields in the 1930s and 1940s, producing high wages and benefits.

Mechanization

Irish mining engineer Richard Sutcliffe invented the first conveyor belt for use in the coal mines of Yorkshire in the early 1900s. Within the first forty years of the 20th century, more than sixty percent of US coal was loaded mechanically rather than by man power. The history of the industry is the history of increasing mechanization. As mechanization continued, fewer miners were needed, and some miners reacted with violence. One of the first machines to arrive at West Virginia's Kanawha field had to be escorted by armed guards. The same machine introduced at a mine in Illinois was operated at a slow speed because the superintendent feared labor troubles.

Despite resistance, mechanization replaced more and more laborers. By 1940, over 2/3 of coal loaded in the large West Virginia fields was done by machine. With the increase of mechanization came much higher wages for those still employed, but hard times for the former miners because there were very few other jobs in or near the camps. Most moved to the cities to find work, or back to the hills where they started.

In 1914 at the peak there were 180,000 anthracite miners; by 1970 only 6,000 remained. At the same time steam engines were phased out in railways and factories, and bituminous coal was used primarily for the generation of electricity. Employment in bituminous peaked at 705,000 men in 1923, falling to 140,000 by 1970 and 70,000 in 2003.

During World War II, the Solid Fuels Administration for War operated government-seized coal mines, either directly or through cooperation with successive Coal Mines Administrations.

In the 1960s a series of mergers saw coal production shift from small, independent coal companies to large, more diversified firms. Several oil companies and electricity producers acquired coal companies or leased Federal coal reserves in the west of the United States. Concerns that competition in the coal industry could decline as a result of these changes were heightened by a sharp rise in coal prices in the wake of the 1973 oil crisis. Coal prices fell in the 1980s, partly in response to oil price decline, but primarily in response to the large increase in supply worldwide which was brought about by the earlier price surge. During this period, the industry in the U.S. moved to low-sulfur coal.

In 1987 Wyoming became the largest coal producing state. As of 2014, all but one out of the 18 coal mines in Wyoming were strip mines. Wyoming's coal reserves total about 69.3 billion tons, or 14.2% of the U.S. coal reserve.

Coal is used primarily to generate electricity, but the rapid drop in natural gas prices after 2010 created severe competition.