| |||

| Courtesy name | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 润之 | ||

| Traditional Chinese | 潤之 | ||

Mao Zedong (/ˈmaʊ

Mao was the son of a wealthy farmer in Shaoshan, Hunan. He had a Chinese nationalist and anti-imperialist outlook early in his life, and was particularly influenced by the events of the Xinhai Revolution of 1911 and May Fourth Movement of 1919. He later adopted Marxism–Leninism while working at Peking University, and became a founding member of the Communist Party of China (CPC), leading the Autumn Harvest Uprising in 1927. During the Chinese Civil War between the Kuomintang (KMT) and the CPC, Mao helped to found the Chinese Workers' and Peasants' Red Army, led the Jiangxi Soviet's radical land policies, and ultimately became head of the CPC during the Long March. Although the CPC temporarily allied with the KMT under the United Front during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), China's civil war resumed after Japan's surrender and in 1949 Mao's forces defeated the Nationalist government, which withdrew to Taiwan.

On October 1, 1949, Mao proclaimed the foundation of the People's Republic of China (PRC), a single-party state controlled by the CPC. In the following years he solidified his control through land reforms and through a psychological victory in the Korean War, as well as through campaigns against landlords, people he termed "counter-revolutionaries", and other perceived enemies of the state. In 1957, he launched a campaign known as the Great Leap Forward that aimed to rapidly transform China's economy from agrarian to industrial. This campaign led to the deadliest famine in history and the deaths of 20–45 million people between 1958 and 1962. In 1966, Mao initiated the Cultural Revolution, a program to remove "counter-revolutionary" elements in Chinese society which lasted 10 years and was marked by violent class struggle, widespread destruction of cultural artifacts, and an unprecedented elevation of Mao's cult of personality. The program is now officially regarded as a "severe setback" for the PRC. In 1972, Mao welcomed American President Richard Nixon in Beijing, signalling the start of a policy

of opening China to the world. After years of ill health, Mao suffered a

series of heart attacks in 1976 and died at the age of 82. He was

succeeded as paramount leader by Premier Hua Guofeng, who was quickly sidelined and replaced by Deng Xiaoping.

A controversial figure, Mao is regarded as one of the most important and influential individuals in modern world history. He is also known as a political intellect, theorist, military strategist, poet, and visionary. Supporters credit him with driving imperialism out of China, modernising the nation and building it into a world power, promoting the status of women, improving education and health care, as well as increasing life expectancy as China's population grew from around 550 million to over 900 million under his leadership. Conversely, his regime has been called autocratic and totalitarian,

and condemned for bringing about mass repression and destroying

religious and cultural artifacts and sites. It was additionally

responsible for vast numbers of deaths with estimates ranging from 30 to

70 million victims through starvation, prison labour and mass executions.

Early life

Youth and the Xinhai Revolution: 1893–1911

Mao Zedong was born on December 26, 1893, in Shaoshan village, Hunan Province, China. His father, Mao Yichang,

was a formerly impoverished peasant who had become one of the

wealthiest farmers in Shaoshan. Growing up in rural Hunan, Mao described

his father as a stern disciplinarian, who would beat him and his three

siblings, the boys Zemin and Zetan, as well as an adopted girl, Zejian. Mao's mother, Wen Qimei, was a devout Buddhist who tried to temper her husband's strict attitude. Mao too became a Buddhist, but abandoned this faith in his mid-teenage years. At age 8, Mao was sent to Shaoshan Primary School. Learning the value systems of Confucianism, he later admitted that he didn't enjoy the classical Chinese texts preaching Confucian morals, instead favouring popular novels like Romance of the Three Kingdoms and Water Margin. At age 13, Mao finished primary education, and his father united him in an arranged marriage to the 17-year-old Luo Yixiu,

thereby uniting their land-owning families. Mao refused to recognise

her as his wife, becoming a fierce critic of arranged marriage and

temporarily moving away. Luo was locally disgraced and died in 1910.

Mao Zedong's childhood home in Shaoshan, in 2010, by which time it had become a tourist destination

While working on his father's farm, Mao read voraciously and developed a "political consciousness" from Zheng Guanying's booklet which lamented the deterioration of Chinese power and argued for the adoption of representative democracy. Interested in history, Mao was inspired by the military prowess and nationalistic fervour of George Washington and Napoleon Bonaparte. His political views were shaped by Gelaohui-led protests which erupted following a famine in Changsha,

the capital of Hunan; Mao supported the protesters' demands, but the

armed forces suppressed the dissenters and executed their leaders.

The famine spread to Shaoshan, where starving peasants seized his

father's grain. He disapproved of their actions as morally wrong, but

claimed sympathy for their situation. At age 16, Mao moved to a higher primary school in nearby Dongshan, where he was bullied for his peasant background.

In 1911, Mao began middle school in Changsha. Revolutionary sentiment was strong in the city, where there was widespread animosity towards Emperor Puyi's absolute monarchy and many were advocating republicanism. The republicans' figurehead was Sun Yat-sen, an American-educated Christian who led the Tongmenghui society. In Changsha, Mao was influenced by Sun's newspaper, The People's Independence (Minli bao), and called for Sun to become president in a school essay. As a symbol of rebellion against the Manchu monarch, Mao and a friend cut off their queue pigtails, a sign of subservience to the emperor.

Inspired by Sun's republicanism, the army rose up across southern China, sparking the Xinhai Revolution. Changsha's governor fled, leaving the city in republican control. Supporting the revolution, Mao joined the rebel army as a private soldier,

but was not involved in fighting. The northern provinces remained loyal

to the emperor, and hoping to avoid a civil war, Sun—proclaimed

"provisional president" by his supporters—compromised with the

monarchist general Yuan Shikai. The monarchy was abolished, creating the Republic of China,

but the monarchist Yuan became president. The revolution over, Mao

resigned from the army in 1912, after six months as a soldier. Around this time, Mao discovered socialism from a newspaper article; proceeding to read pamphlets by Jiang Kanghu, the student founder of the Chinese Socialist Party, Mao remained interested yet unconvinced by the idea.

Fourth Normal School of Changsha: 1912–19

Over the next few years, Mao Zedong enrolled and dropped out of a

police academy, a soap-production school, a law school, an economics

school, and the government-run Changsha Middle School. Studying independently, he spent much time in Changsha's library, reading core works of classical liberalism such as Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations and Montesquieu's The Spirit of the Laws, as well as the works of western scientists and philosophers such as Darwin, Mill, Rousseau, and Spencer. Viewing himself as an intellectual, years later he admitted that at this time he thought himself better than working people. He was inspired by Friedrich Paulsen,

whose liberal emphasis on individualism led Mao to believe that strong

individuals were not bound by moral codes but should strive for the

greater good, and that the "end justifies the means" conclusion of Consequentialism.

His father saw no use in his son's intellectual pursuits, cut off his

allowance and forced him to move into a hostel for the destitute.

Mao Zedong in 1913

Mao desired to become a teacher and enrolled at the Fourth Normal

School of Changsha, which soon merged with the First Normal School of

Changsha, widely seen as the best in Hunan. Befriending Mao, professor Yang Changji urged him to read a radical newspaper, New Youth (Xin qingnian), the creation of his friend Chen Duxiu, a dean at Peking University. Although a Chinese nationalist, Chen argued that China must look to the west to cleanse itself of superstition and autocracy. Mao published his first article in New Youth in April 1917, instructing readers to increase their physical strength to serve the revolution. He joined the Society for the Study of Wang Fuzhi (Chuan-shan Hsüeh-she), a revolutionary group founded by Changsha literati who wished to emulate the philosopher Wang Fuzhi.

In his first school year, Mao befriended an older student, Xiao Zisheng; together they went on a walking tour of Hunan, begging and writing literary couplets to obtain food.

A popular student, in 1915 Mao was elected secretary of the Students

Society. He organized the Association for Student Self-Government and

led protests against school rules. In spring 1917, he was elected to command the students' volunteer army, set up to defend the school from marauding soldiers. Increasingly interested in the techniques of war, he took a keen interest in World War I, and also began to develop a sense of solidarity with workers. Mao undertook feats of physical endurance with Xiao Zisheng and Cai Hesen,

and with other young revolutionaries they formed the Renovation of the

People Study Society in April 1918 to debate Chen Duxiu's ideas.

Desiring personal and societal transformation, the Society gained 70–80

members, many of whom would later join the Communist Party. Mao graduated in June 1919, ranked third in the year.

Early revolutionary activity

Beijing, Anarchism, and Marxism: 1917–19

Mao moved to Beijing, where his mentor Yang Changji had taken a job at Peking University. Yang thought Mao exceptionally "intelligent and handsome", securing him a job as assistant to the university librarian Li Dazhao, an early Chinese Communist. Li authored a series of New Youth articles on the October Revolution in Russia, during which the Communist Bolshevik Party under the leadership of Vladimir Lenin had seized power. Lenin was an advocate of the socio-political theory of Marxism, first developed by the German sociologists Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, and Li's articles brought an understanding of Marxism to the Chinese revolutionary movement. Becoming "more and more radical", Mao was influenced by Peter Kropotkin's anarchism, but joined Li's Study Group and "developed rapidly toward Marxism" during the winter of 1919.

Paid a low wage, Mao lived in a cramped room with seven other

Hunanese students, but believed that Beijing's beauty offered "vivid and

living compensation".

At the university, Mao was widely snubbed by other students due to his

rural Hunanese accent and lowly position. He joined the university's

Philosophy and Journalism Societies and attended lectures and seminars

by the likes of Chen Duxiu, Hu Shi, and Qian Xuantong. Mao's time in Beijing ended in the spring of 1919, when he travelled to Shanghai with friends who were preparing to leave for France.

He did not return to Shaoshan, where his mother was terminally ill. She

died in October 1919, with her husband dying in January 1920.

New Culture and political protests, 1919–20

On May 4, 1919, students in Beijing gathered at the Gate of Heavenly

Peace to protest the Chinese government's weak resistance to Japanese

expansion in China. Patriots were outraged at the influence given to

Japan in the Twenty-One Demands in 1915, the complicity of Duan Qirui's Beiyang Government, and the betrayal of China in the Treaty of Versailles, wherein Japan was allowed to receive territories in Shandong which had been surrendered by Germany. These demonstrations ignited the nationwide May Fourth Movement and fueled the New Culture Movement which blamed China's diplomatic defeats on social and cultural backwardness.

In Changsha, Mao had begun teaching history at the Xiuye Primary School and organizing protests against the pro-Duan Governor of Hunan Province, Zhang Jingyao, popularly known as "Zhang the Venomous" due to his corrupt and violent rule. In late May, Mao co-founded the Hunanese Student Association with He Shuheng and Deng Zhongxia, organizing a student strike for June and in July 1919 began production of a weekly radical magazine, Xiang River Review (Xiangjiang pinglun).

Using vernacular language that would be understandable to the majority

of China's populace, he advocated the need for a "Great Union of the

Popular Masses", strengthened trade unions able to wage non-violent

revolution. His ideas were not Marxist, but heavily influenced by Kropotkin's concept of mutual aid.

Students in Beijing rallied during the May Fourth Movement.

Zhang banned the Student Association, but Mao continued publishing after assuming editorship of the liberal magazine New Hunan (Xin Hunan) and offered articles in popular local newspaper Justice (Ta Kung Po). Several of these advocated feminist views, calling for the liberation of women in Chinese society; Mao was influenced by his forced arranged-marriage.

In December 1919, Mao helped organise a general strike in Hunan,

securing some concessions, but Mao and other student leaders felt

threatened by Zhang, and Mao returned to Beijing, visiting the

terminally ill Yang Changji.

Mao found that his articles had achieved a level of fame among the

revolutionary movement, and set about soliciting support in overthrowing

Zhang. Coming across newly translated Marxist literature by Thomas Kirkup, Karl Kautsky, and Marx and Engels—notably The Communist Manifesto—he came under their increasing influence, but was still eclectic in his views.

Mao visited Tianjin, Jinan, and Qufu, before moving to Shanghai, where he worked as a laundryman and met Chen Duxiu,

noting that Chen's adoption of Marxism "deeply impressed me at what was

probably a critical period in my life". In Shanghai, Mao met an old

teacher of his, Yi Peiji, a revolutionary and member of the Kuomintang (KMT), or Chinese Nationalist Party, which was gaining increasing support and influence. Yi introduced Mao to General Tan Yankai,

a senior KMT member who held the loyalty of troops stationed along the

Hunanese border with Guangdong. Tan was plotting to overthrow Zhang, and

Mao aided him by organizing the Changsha students. In June 1920, Tan

led his troops into Changsha, and Zhang fled. In the subsequent

reorganization of the provincial administration, Mao was appointed

headmaster of the junior section of the First Normal School. Now

receiving a large income, he married Yang Kaihui in the winter of 1920.

Founding the Communist Party of China: 1921–22

Location of the first Congress of the Chinese Communist Party in July 1921, in Xintiandi, former French Concession, Shanghai

The Communist Party of China was founded by Chen Duxiu and Li Dazhao in the French concession

of Shanghai in 1921 as a study society and informal network. Mao set up

a Changsha branch, also establishing a branch of the Socialist Youth

Corps. Opening a bookstore under the control of his new Cultural Book

Society, its purpose was to propagate revolutionary literature

throughout Hunan. He was involved in the movement for Hunan autonomy, in the hope that a Hunanese constitution would increase civil liberties

and make his revolutionary activity easier. When the movement was

successful in establishing provincial autonomy under a new warlord, Mao

forgot his involvement.

By 1921, small Marxist groups existed in Shanghai, Beijing, Changsha,

Wuhan, Guangzhou, and Jinan; it was decided to hold a central meeting,

which began in Shanghai on July 23, 1921. The first session of the National Congress of the Communist Party of China

was attended by 13 delegates, Mao included. After the authorities sent a

police spy to the congress, the delegates moved to a boat on South Lake

near Jiaxing, in Zhejiang, to escape detection. Although Soviet and Comintern

delegates attended, the first congress ignored Lenin's advice to accept

a temporary alliance between the Communists and the "bourgeois

democrats" who also advocated national revolution; instead they stuck to

the orthodox Marxist belief that only the urban proletariat could lead a

socialist revolution.

Mao was now party secretary for Hunan stationed in Changsha, and to build the party there he followed a variety of tactics.

In August 1921, he founded the Self-Study University, through which

readers could gain access to revolutionary literature, housed in the

premises of the Society for the Study of Wang Fuzhi, a Qing dynasty Hunanese philosopher who had resisted the Manchus. He joined the YMCA Mass Education Movement to fight illiteracy, though he edited the textbooks to include radical sentiments. He continued organizing workers to strike against the administration of Hunan Governor Zhao Hengti. Yet labor issues remained central. The successful and famous Anyuan coal mines strikes (contrary to later Party historians) depended on both "proletarian" and "bourgeois" strategies. Liu Shaoqi and Li Lisan

and Mao not only mobilised the miners, but formed schools and

cooperatives and engaged local intellectuals, gentry, military officers,

merchants, Red Gang dragon heads and even church clergy.

Mao claimed that he missed the July 1922 Second Congress of the

Communist Party in Shanghai because he lost the address. Adopting

Lenin's advice, the delegates agreed to an alliance with the "bourgeois

democrats" of the KMT for the good of the "national revolution".

Communist Party members joined the KMT, hoping to push its politics

leftward.

Mao enthusiastically agreed with this decision, arguing for an alliance

across China's socio-economic classes. Mao was a vocal anti-imperialist

and in his writings he lambasted the governments of Japan, UK and US,

describing the latter as "the most murderous of hangmen".

Collaboration with the Kuomintang: 1922–27

At the Third Congress of the Communist Party in Shanghai in June

1923, the delegates reaffirmed their commitment to working with the KMT.

Supporting this position, Mao was elected to the Party Committee,

taking up residence in Shanghai. At the First KMT Congress, held in Guangzhou

in early 1924, Mao was elected an alternate member of the KMT Central

Executive Committee, and put forward four resolutions to decentralise

power to urban and rural bureaus. His enthusiastic support for the KMT

earned him the suspicion of Li Li-san, his Hunan comrade.

In late 1924, Mao returned to Shaoshan, perhaps to recuperate

from an illness. He found that the peasantry were increasingly restless

and some had seized land from wealthy landowners to found communes. This

convinced him of the revolutionary potential of the peasantry, an idea

advocated by the KMT leftists but not the Communists. He returned to Guangzhou to run the 6th term of the KMT's Peasant Movement Training Institute from May to September 1926.

The Peasant Movement Training Institute under Mao trained cadre and

prepared them for militant activity, taking them through military

training exercises and getting them to study basic left-wing texts. In the winter of 1925, Mao fled to Guangzhou after his revolutionary activities attracted the attention of Zhao's regional authorities.

When party leader Sun Yat-sen died in May 1925, he was succeeded by Chiang Kai-shek, who moved to marginalise the left-KMT and the Communists. Mao nevertheless supported Chiang's National Revolutionary Army, who embarked on the Northern Expedition attack in 1926 on warlords.

In the wake of this expedition, peasants rose up, appropriating the

land of the wealthy landowners, who were in many cases killed. Such

uprisings angered senior KMT figures, who were themselves landowners,

emphasizing the growing class and ideological divide within the

revolutionary movement.

Revolution is not a dinner party, nor an essay, nor a painting, nor a piece of embroidery; it cannot be so refined, so leisurely and gentle, so temperate, kind, courteous, restrained and magnanimous. A revolution is an insurrection, an act of violence by which one class overthrows another. — Mao, February 1927

In March 1927, Mao appeared at the Third Plenum of the KMT Central

Executive Committee in Wuhan, which sought to strip General Chiang of

his power by appointing Wang Jingwei

leader. There, Mao played an active role in the discussions regarding

the peasant issue, defending a set of "Regulations for the Repression of

Local Bullies and Bad Gentry", which advocated the death penalty or

life imprisonment for anyone found guilty of counter-revolutionary activity, arguing that in a revolutionary situation, "peaceful methods cannot suffice".

In April 1927, Mao was appointed to the KMT's five-member Central Land

Committee, urging peasants to refuse to pay rent. Mao led another group

to put together a "Draft Resolution on the Land Question", which called

for the confiscation of land belonging to "local bullies and bad gentry,

corrupt officials, militarists and all counter-revolutionary elements

in the villages". Proceeding to carry out a "Land Survey", he stated

that anyone owning over 30 mou (four and a half acres),

constituting 13% of the population, were uniformly

counter-revolutionary. He accepted that there was great variation in

revolutionary enthusiasm across the country, and that a flexible policy

of land redistribution was necessary.

Presenting his conclusions at the Enlarged Land Committee meeting, many

expressed reservations, some believing that it went too far, and others

not far enough. Ultimately, his suggestions were only partially

implemented.

Civil War

The Nanchang and Autumn Harvest Uprisings: 1927

Fresh from the success of the Northern Expedition against the

warlords, Chiang turned on the Communists, who by now numbered in the

tens of thousands across China. Chiang ignored the orders of the

Wuhan-based left KMT government and marched on Shanghai, a city

controlled by Communist militias. As the Communists awaited Chiang's

arrival, he loosed the White Terror, massacring 5000 with the aid of the Green Gang. In Beijing, 19 leading Communists were killed by Zhang Zuolin.

That May, tens of thousands of Communists and those suspected of being

communists were killed, and the CPC lost approximately 15,000 of its

25,000 members.

Flag of the Chinese Workers' and Peasants' Red Army

Eagles cleave the air,

Fish glide in the limpid deep;

Under freezing skies a million

creatures contend in freedom.

Brooding over this immensity,

I ask, on this boundless land

Who rules over man's destiny?

Fish glide in the limpid deep;

Under freezing skies a million

creatures contend in freedom.

Brooding over this immensity,

I ask, on this boundless land

Who rules over man's destiny?

poem "Changsha", September 1927

The CPC continued supporting the Wuhan KMT government, a position Mao initially supported, but by the time of the CPC's Fifth Congress he had changed his mind, deciding to stake all hope on the peasant militia. The question was rendered moot when the Wuhan government expelled all Communists from the KMT on July 15. The CPC founded the Workers' and Peasants' Red Army of China, better known as the "Red Army", to battle Chiang. A battalion led by General Zhu De was ordered to take the city of Nanchang on August 1, 1927, in what became known as the Nanchang Uprising. They were initially successful, but were forced into retreat after five days, marching south to Shantou, and from there they were driven into the wilderness of Fujian. Mao was appointed commander-in-chief of the Red Army and led four regiments against Changsha in the Autumn Harvest Uprising,

in the hope of sparking peasant uprisings across Hunan. On the eve of

the attack, Mao composed a poem—the earliest of his to survive—titled

"Changsha". His plan was to attack the KMT-held city from three

directions on September 9, but the Fourth Regiment deserted to the KMT

cause, attacking the Third Regiment. Mao's army made it to Changsha, but

could not take it; by September 15, he accepted defeat and with 1000

survivors marched east to the Jinggang Mountains of Jiangxi.

Jung Chang and Jon Halliday claim that the uprising was in fact

sabotaged by Mao to allow him to prevent a group of KMT soldiers from

defecting to any other CPC leader.

Chang and Halliday also claim that Mao talked the other leaders

(including Russian diplomats at the Soviet consulate in Changsha who,

Chang and Halliday claim, had been controlling much of the CPC activity)

into striking only at Changsha, then abandoning it. Chang and Halliday

report a view sent to Moscow by the secretary of the Soviet Consulate in

Changsha that the retreat was "the most despicable treachery and

cowardice."

Base in Jinggangshan: 1927–1928

Mao in 1927

The CPC Central Committee, hiding in Shanghai, expelled Mao from

their ranks and from the Hunan Provincial Committee, as punishment for

his "military opportunism", for his focus on rural activity, and for

being too lenient with "bad gentry". They nevertheless adopted three

policies he had long championed: the immediate formation of Workers' councils, the confiscation of all land without exemption, and the rejection of the KMT. Mao's response was to ignore them. He established a base in Jinggangshan City,

an area of the Jinggang Mountains, where he united five villages as a

self-governing state, and supported the confiscation of land from rich

landlords, who were "re-educated" and sometimes executed. He ensured

that no massacres took place in the region, and pursued a more lenient

approach than that advocated by the Central Committee.

He proclaimed that "Even the lame, the deaf and the blind could all

come in useful for the revolutionary struggle", he boosted the army's

numbers, incorporating two groups of bandits into his army, building a force of around 1,800 troops.

He laid down rules for his soldiers: prompt obedience to orders, all

confiscations were to be turned over to the government, and nothing was

to be confiscated from poorer peasants. In doing so, he molded his men

into a disciplined, efficient fighting force.

When the enemy advances, we retreat.

When the enemy rests, we harass him.

When the enemy avoids a battle, we attack.

When the enemy retreats, we advance.

When the enemy rests, we harass him.

When the enemy avoids a battle, we attack.

When the enemy retreats, we advance.

In spring 1928, the Central Committee ordered Mao's troops to

southern Hunan, hoping to spark peasant uprisings. Mao was skeptical,

but complied. They reached Hunan, where they were attacked by the KMT

and fled after heavy losses. Meanwhile, KMT troops had invaded

Jinggangshan, leaving them without a base. Wandering the countryside, Mao's forces came across a CPC regiment led by General Zhu De and Lin Biao;

they united, and attempted to retake Jinggangshan. They were initially

successful, but the KMT counter-attacked, and pushed the CPC back; over

the next few weeks, they fought an entrenched guerrilla war in the

mountains.

The Central Committee again ordered Mao to march to south Hunan, but he

refused, and remained at his base. Contrastingly, Zhu complied, and led

his armies away. Mao's troops fended the KMT off for 25 days while he

left the camp at night to find reinforcements. He reunited with the

decimated Zhu's army, and together they returned to Jinggangshan and

retook the base. There they were joined by a defecting KMT regiment and Peng Dehuai's

Fifth Red Army. In the mountainous area they were unable to grow enough

crops to feed everyone, leading to food shortages throughout the

winter.

Jiangxi Soviet Republic of China: 1929–1934

In January 1929, Mao and Zhu evacuated the base with 2,000 men and a

further 800 provided by Peng, and took their armies south, to the area

around Tonggu and Xinfeng in Jiangxi. The evacuation led to a drop in morale, and many troops became disobedient and began thieving; this worried Li Lisan and the Central Committee, who saw Mao's army as lumpenproletariat, that were unable to share in proletariat class consciousness.

In keeping with orthodox Marxist thought, Li believed that only the

urban proletariat could lead a successful revolution, and saw little

need for Mao's peasant guerrillas; he ordered Mao to disband his army

into units to be sent out to spread the revolutionary message. Mao

replied that while he concurred with Li's theoretical position, he would

not disband his army nor abandon his base. Both Li and Mao saw the Chinese revolution as the key to world revolution,

believing that a CPC victory would spark the overthrow of global

imperialism and capitalism. In this, they disagreed with the official

line of the Soviet government and Comintern. Officials in Moscow desired

greater control over the CPC and removed Li from power by calling him

to Russia for an inquest into his errors. They replaced him with Soviet-educated Chinese Communists, known as the "28 Bolsheviks", two of whom, Bo Gu and Zhang Wentian,

took control of the Central Committee. Mao disagreed with the new

leadership, believing they grasped little of the Chinese situation, and

he soon emerged as their key rival.

Mao in 1931

In February 1930, Mao created the Southwest Jiangxi Provincial Soviet Government in the region under his control. In November, he suffered emotional trauma after his wife and sister were captured and beheaded by KMT general He Jian. Mao then married He Zizhen, an 18-year-old revolutionary who bore him five children over the following nine years.

Facing internal problems, members of the Jiangxi Soviet accused him of

being too moderate, and hence anti-revolutionary. In December, they

tried to overthrow Mao, resulting in the Futian incident, during which Mao's loyalists tortured many and executed between 2000 and 3000 dissenters. The CPC Central Committee moved to Jiangxi which it saw as a secure area. In November it proclaimed Jiangxi to be the Soviet Republic of China,

an independent Communist-governed state. Although he was proclaimed

Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars, Mao's power was

diminished, as his control of the Red Army was allocated to Zhou Enlai. Meanwhile, Mao recovered from tuberculosis.

The KMT armies adopted a policy of encirclement and annihilation

of the Red armies. Outnumbered, Mao responded with guerrilla tactics

influenced by the works of ancient military strategists like Sun Tzu,

but Zhou and the new leadership followed a policy of open confrontation

and conventional warfare. In doing so, the Red Army successfully

defeated the first and second encirclements.

Angered at his armies' failure, Chiang Kai-shek personally arrived to

lead the operation. He too faced setbacks and retreated to deal with the

further Japanese incursions into China.

As a result of the KMT's change of focus to the defence of China

against Japanese expansionism, the Red Army was able to expand its area

of control, eventually encompassing a population of 3 million.

Mao proceeded with his land reform program. In November 1931 he

announced the start of a "land verification project" which was expanded

in June 1933. He also orchestrated education programs and implemented

measures to increase female political participation. Chiang viewed the Communists as a greater threat than the Japanese and returned to Jiangxi, where he initiated the fifth encirclement campaign,

which involved the construction of a concrete and barbed wire "wall of

fire" around the state, which was accompanied by aerial bombardment, to

which Zhou's tactics proved ineffective. Trapped inside, morale among

the Red Army dropped as food and medicine became scarce. The leadership

decided to evacuate.

The Long March: 1934–1935

On October 14, 1934, the Red Army broke through the KMT line on the

Jiangxi Soviet's south-west corner at Xinfeng with 85,000 soldiers and

15,000 party cadres and embarked on the "Long March".

In order to make the escape, many of the wounded and the ill, as well

as women and children, were left behind, defended by a group of

guerrilla fighters whom the KMT massacred. The 100,000 who escaped headed to southern Hunan, first crossing the Xiang River after heavy fighting, and then the Wu River, in Guizhou where they took Zunyi in January 1935. Temporarily resting in the city, they held a conference; here, Mao was elected to a position of leadership, becoming Chairman of the Politburo, and de facto leader of both Party and Red Army, in part because his candidacy was supported by Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin. Insisting that they operate as a guerrilla force, he laid out a destination: the Shenshi Soviet in Shaanxi,

Northern China, from where the Communists could focus on fighting the

Japanese. Mao believed that in focusing on the anti-imperialist

struggle, the Communists would earn the trust of the Chinese people, who

in turn would renounce the KMT.

From Zunyi, Mao led his troops to Loushan Pass,

where they faced armed opposition but successfully crossed the river.

Chiang flew into the area to lead his armies against Mao, but the

Communists outmanoeuvred him and crossed the Jinsha River. Faced with the more difficult task of crossing the Tatu River, they managed it by fighting a battle over the Luding Bridge in May, taking Luding. Marching through the mountain ranges around Ma'anshan, in Moukung, Western Szechuan, they encountered the 50,000-strong CPC Fourth Front Army of Zhang Guotao, and together proceeded to Maoerhkai and then Gansu. Zhang and Mao disagreed over what to do; the latter wished to proceed to Shaanxi, while Zhang wanted to retreat east to Tibet or Sikkim, far from the KMT threat. It was agreed that they would go their separate ways, with Zhu De joining Zhang. Mao's forces proceeded north, through hundreds of kilometres of Grasslands, an area of quagmire where they were attacked by Manchu tribesman and where many soldiers succumbed to famine and disease. Finally reaching Shaanxi, they fought off both the KMT and an Islamic cavalry militia before crossing the Min Mountains and Mount Liupan and reaching the Shenshi Soviet; only 7,000–8000 had survived.

The Long March cemented Mao's status as the dominant figure in the

party. In November 1935, he was named chairman of the Military

Commission. From this point onward, Mao was the Communist Party's

undisputed leader, even though he would not become party chairman until

1943.

Jung Chang and Jon Halliday offered an alternative account on many events during this period in their book Mao: The Unknown Story.

For example, there was no battle at Luding and the CPC crossed the

bridge unopposed, the Long March was not a strategy of the CPC but

devised by Chiang Kai-shek, and Mao and other top CPC leaders did not

walk the Long March but were carried on litters.

However, although well received in the popular press, Chang and

Halliday's work has been highly criticized by professional historians.

Alliance with the Kuomintang: 1935–1940

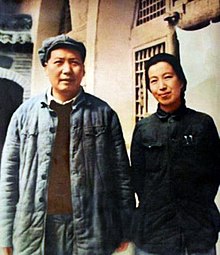

Mao Zedong, Zhang Guotao in Yan'an, 1937

Mao's troops arrived at the Yan'an

Soviet during October 1935 and settled in Pao An, until spring 1936.

While there, they developed links with local communities, redistributed

and farmed the land, offered medical treatment, and began literacy

programs. Mao now commanded 15,000 soldiers, boosted by the arrival of He Long's men from Hunan and the armies of Zhu De and Zhang Guotao returned from Tibet.

In February 1936, they established the North West Anti-Japanese Red

Army University in Yan'an, through which they trained increasing numbers

of new recruits.

In January 1937, they began the "anti-Japanese expedition", that sent

groups of guerrilla fighters into Japanese-controlled territory to

undertake sporadic attacks. In May 1937, a Communist Conference was held in Yan'an to discuss the situation. Western reporters also arrived in the "Border Region" (as the Soviet had been renamed); most notable were Edgar Snow, who used his experiences as a basis for Red Star Over China, and Agnes Smedley, whose accounts brought international attention to Mao's cause.

In an effort to defeat the Japanese, Mao (left) agreed to collaborate with Chiang (right).

Mao in 1938, writing On Protracted War

On the Long March, Mao's wife He Zizen had been injured by a shrapnel

wound to the head. She traveled to Moscow for medical treatment; Mao

proceeded to divorce her and marry an actress, Jiang Qing. Mao moved into a cave-house and spent much of his time reading, tending his garden and theorizing.

He came to believe that the Red Army alone was unable to defeat the

Japanese, and that a Communist-led "government of national defence"

should be formed with the KMT and other "bourgeois nationalist" elements

to achieve this goal. Although despising Chiang Kai-shek as a "traitor to the nation",

on May 5, he telegrammed the Military Council of the Nanking National

Government proposing a military alliance, a course of action advocated

by Stalin. Although Chiang intended to ignore Mao's message and continue the civil war, he was arrested by one of his own generals, Zhang Xueliang, in Xi'an, leading to the Xi'an Incident; Zhang forced Chiang to discuss the issue with the Communists, resulting in the formation of a United Front with concessions on both sides on December 25, 1937.

The Japanese had taken both Shanghai and Nanking (Nanjing)—resulting in the Nanking Massacre, an atrocity Mao never spoke of all his life—and was pushing the Kuomintang government inland to Chungking. The Japanese's brutality led to increasing numbers of Chinese joining the fight, and the Red Army grew from 50,000 to 500,000. In August 1938, the Red Army formed the New Fourth Army and the Eighth Route Army, which were nominally under the command of Chiang's National Revolutionary Army. In August 1940, the Red Army initiated the Hundred Regiments Campaign,

in which 400,000 troops attacked the Japanese simultaneously in five

provinces. It was a military success that resulted in the death of

20,000 Japanese, the disruption of railways and the loss of a coal mine. From his base in Yan'an, Mao authored several texts for his troops, including Philosophy of Revolution, which offered an introduction to the Marxist theory of knowledge; Protracted Warfare, which dealt with guerilla and mobile military tactics; and New Democracy, which laid forward ideas for China's future.

Resuming civil war: 1940–1949

In 1944, the Americans sent a special diplomatic envoy, called the Dixie Mission, to the Communist Party of China. According to Edwin Moise, in Modern China: A History 2nd Edition:

Most of the Americans were favourably impressed. The CPC seemed less corrupt, more unified, and more vigorous in its resistance to Japan than the KMT. United States fliers shot down over North China ... confirmed to their superiors that the CPC was both strong and popular over a broad area. In the end, the contacts with the USA developed with the CPC led to very little.

After the end of World War II, the U.S. continued their military

assistance to Chiang Kai-shek and his KMT government forces against the People's Liberation Army (PLA) led by Mao Zedong during the civil war. Likewise, the Soviet Union

gave quasi-covert support to Mao by their occupation of north east

China, which allowed the PLA to move in en masse and take large supplies

of arms left by the Japanese's Kwantung Army.

To enhance the Red Army's military operations, Mao as the

Chairman of the Communist Party of China, named his close associate

General Zhu De to be its Commander-in-Chief.

In 1948, under direct orders from Mao, the People's Liberation Army starved out the Kuomintang forces occupying the city of Changchun. At least 160,000 civilians are believed to have perished during the siege, which lasted from June until October. PLA lieutenant colonel Zhang Zhenglu, who documented the siege in his book White Snow, Red Blood, compared it to Hiroshima: "The casualties were about the same. Hiroshima took nine seconds; Changchun took five months." On January 21, 1949, Kuomintang forces suffered great losses in decisive battles against Mao's forces. In the early morning of December 10, 1949, PLA troops laid siege to Chongqing and Chengdu on mainland China, and Chiang Kai-shek fled from the mainland to Formosa (Taiwan).

Leadership of China

Mao Zedong declares the founding of the modern People's Republic of China on October 1, 1949.

The People's Republic of China was established on October 1, 1949. It

was the culmination of over two decades of civil and international

wars. Mao's famous phrase "The Chinese people have stood up" (Chinese: 中國人民從此站起來了) associated with the establishment of the People's Republic of China was not used in the speech he delivered from the Gate of Heavenly Peace (Tian'anmen) on October 1.

Mao took up residence in Zhongnanhai, a compound next to the Forbidden City in Beijing, and there he ordered the construction of an indoor swimming pool and other buildings. Mao's physician Li Zhisui

described him as conducting business either in bed or by the side of

the pool, preferring not to wear formal clothes unless absolutely

necessary. Li's book, The Private Life of Chairman Mao, is regarded as controversial, especially by those sympathetic to Mao. Mao often visited his villa in Wuhan between 1960 and 1974; the villa includes a garden, living quarters, conference room, bomb shelter and swimming pool.

Mao with his fourth wife, Jiang Qing, called "Madame Mao", 1946

In October 1950, Mao made the decision to send the People's Volunteer Army (PVA), a special unit of the People's Liberation Army, into the Korean war and fight as well as to reinforce the armed forces of North Korea, the Korean People's Army,

which had been in full retreat. Historical records showed that Mao

directed the PVA campaigns to the minutest details. As the Chairman of

the CPC's Central Military Commission (CMC), he was also the Supreme

Commander in Chief of the PLA and the People's Republic and Chairman of

the ruling CPC. The PVA was under the overall command of then newly

installed Premier Zhou Enlai, with General Peng Dehuai as field commander and political commissar.

During the land reform, a significant numbers of landlords and well-to-do peasants were beaten to death at mass meetings organised by the Communist Party as land was taken from them and given to poorer peasants, which significantly reduced economic inequality.The Campaign to Suppress Counter-revolutionaries,

involved public executions that targeted mainly former Kuomintang

officials, businessmen accused of "disturbing" the market, former

employees of Western companies and intellectuals whose loyalty was

suspect. In 1976, the U.S. State department estimated as many as a million were killed in the land reform, and 800,000 killed in the counter-revolutionary campaign.

Mao himself claimed that a total of 700,000 people were killed in

attacks on "counter-revolutionaries" during the years 1950–1952.

However, because there was a policy to select "at least one landlord,

and usually several, in virtually every village for public execution", the number of deaths range between 2 million and 5 million. In addition, at least 1.5 million people, perhaps as many as 4 to 6 million, were sent to "reform through labour" camps where many perished. Mao played a personal role in organizing the mass repressions and established a system of execution quotas, which were often exceeded. He defended these killings as necessary for the securing of power.

Mao at Joseph Stalin's 70th birthday celebration in Moscow, December 1949

The Mao government is generally credited with eradicating both consumption and production of opium during the 1950s using unrestrained repression and social reform.

Ten million addicts were forced into compulsory treatment, dealers were

executed, and opium-producing regions were planted with new crops.

Remaining opium production shifted south of the Chinese border into the Golden Triangle region.

Starting in 1951, Mao initiated two successive movements in an

effort to rid urban areas of corruption by targeting wealthy capitalists

and political opponents, known as the three-anti/five-anti campaigns.

Whereas the three-anti campaign was a focused purge of government,

industrial and party officials, the five-anti campaign set its sights

slightly broader, targeting capitalist elements in general.

Workers denounced their bosses, spouses turned on their spouses, and

children informed on their parents; the victims were often humiliated at

struggle sessions,

a method designed to intimidate and terrify people to the maximum. Mao

insisted that minor offenders be criticised and reformed or sent to

labour camps, "while the worst among them should be shot". These

campaigns took several hundred thousand additional lives, the vast

majority via suicide.

Mao and Zhou Enlai meeting with Dalai Lama (right) and Panchen Lama (left) to celebrate Tibetan New Year, Beijing, 1955

In Shanghai, suicide by jumping from tall buildings became so

commonplace that residents avoided walking on the pavement near

skyscrapers for fear that suicides might land on them.

Some biographers have pointed out that driving those perceived as

enemies to suicide was a common tactic during the Mao-era. For example,

in his biography of Mao, Philip Short notes that in the Yan'an Rectification Movement, Mao gave explicit instructions that "no cadre is to be killed", but in practice allowed security chief Kang Sheng to drive opponents to suicide and that "this pattern was repeated throughout his leadership of the People's Republic".

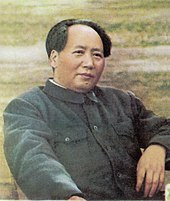

Photo of Mao Zedong sitting, published in "Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-Tung", ca. 1955

Following the consolidation of power, Mao launched the First Five-Year Plan (1953–1958), which aimed to end Chinese dependence upon agriculture in order to become a world power. With the Soviet Union's assistance, new industrial plants were built and agricultural production eventually fell to a point where industry was beginning to produce enough capital that China no longer needed the USSR's support. The success of the First-Five Year Plan was to encourage Mao to instigate the Second Five-Year Plan in 1958. Mao also launched a phase of rapid collectivization. The CPC introduced price controls as well as a Chinese character simplification aimed at increasing literacy. Large-scale industrialization projects were also undertaken.

Programs pursued during this time include the Hundred Flowers Campaign,

in which Mao indicated his supposed willingness to consider different

opinions about how China should be governed. Given the freedom to

express themselves, liberal and intellectual Chinese began opposing the

Communist Party and questioning its leadership. This was initially

tolerated and encouraged. After a few months, however, Mao's government

reversed its policy and persecuted those who had criticised the party,

totaling perhaps 500,000, as well as those who were merely alleged to have been critical, in what is called the Anti-Rightist Movement. Authors such as Jung Chang have alleged that the Hundred Flowers Campaign was merely a ruse to root out "dangerous" thinking.

Li Zhisui, Mao's physician, suggested that Mao had initially seen

the policy as a way of weakening opposition to him within the party and

that he was surprised by the extent of criticism and the fact that it

came to be directed at his own leadership.

It was only then that he used it as a method of identifying and

subsequently persecuting those critical of his government. The Hundred

Flowers movement led to the condemnation, silencing, and death of many

citizens, also linked to Mao's Anti-Rightist Movement, resulting in

deaths possibly in the millions.

Great Leap Forward

Mao with Nikita Khrushchev, Ho Chi Minh and Soong Ching-ling during a state dinner in Beijing, 1959

In January 1958, Mao launched the second Five-Year Plan, known as the Great Leap Forward,

a plan intended as an alternative model for economic growth to the

Soviet model focusing on heavy industry that was advocated by others in

the party. Under this economic program, the relatively small

agricultural collectives that had been formed to date were rapidly

merged into far larger people's communes,

and many of the peasants were ordered to work on massive infrastructure

projects and on the production of iron and steel. Some private food

production was banned, and livestock and farm implements were brought

under collective ownership.

Under the Great Leap Forward, Mao and other party leaders ordered

the implementation of a variety of unproven and unscientific new

agricultural techniques by the new communes. The combined effect of the

diversion of labour to steel production and infrastructure projects, and

cyclical natural disasters led to an approximately 15% drop in grain production in 1959 followed by a further 10% decline in 1960 and no recovery in 1961.

In an effort to win favour with their superiors and avoid being

purged, each layer in the party hierarchy exaggerated the amount of

grain produced under them. Based upon the fabricated success, party

cadres were ordered to requisition a disproportionately high amount of

that fictitious harvest for state use, primarily for use in the cities

and urban areas but also for export. The result, compounded in some

areas by drought and in others by floods, was that rural peasants were

left with little food for themselves and many millions starved to death

in the Great Chinese Famine.

China's population suffered from the Great Famine during the late 20th

century. This came as a result of the lack of food production and

distribution to the population of China. The people of urban areas in

China were given food stamps each month, but the people of rural areas

were expected to grow their own crops and give some of the crops back to

the government. The deaths in the rural parts of China out ranked the

ones in the Urban cities. Also, the government of China continued to

export food to other countries during the Great Famine; this food could

have been used to feed the starving citizens. These factors lead to the

catastrophic death of about 52 million citizens. The famine was a direct cause of the death of some 30 million Chinese peasants between 1959 and 1962.

Further, many children who became emaciated and malnourished during

years of hardship and struggle for survival died shortly after the Great

Leap Forward came to an end in 1962.

The extent of Mao's knowledge of the severity of the situation

has been disputed. Mao's physician believed that he may have been

unaware of the extent of the famine, partly due to a reluctance to

criticise his policies, and the willingness of his staff to exaggerate

or outright fake reports regarding food production. Upon learning of the extent of the starvation, Mao vowed to stop eating meat, an action followed by his staff.

Hong Kong-based historian Frank Dikötter, challenged the notion that Mao did not know about the famine throughout the country until it was too late:

The idea that the state mistakenly took too much grain from the countryside because it assumed that the harvest was much larger than it was is largely a myth—at most partially true for the autumn of 1958 only. In most cases the party knew very well that it was starving its own people to death. At a secret meeting in the Jinjiang Hotel in Shanghai dated March 25, 1959, Mao specifically ordered the party to procure up to one third of all the grain, much more than had ever been the case. At the meeting he announced that "To distribute resources evenly will only ruin the Great Leap Forward. When there is not enough to eat, people starve to death. It is better to let half of the people die so that the other half can eat their fill."

Professor Emeritus Thomas P. Bernstein of Columbia University offered his view on Mao's statement on starvation in the March 25, 1959, meeting:

Some scholars believe that this shows Mao's readiness to accept mass death on an immense scale. My own view is that this is an instance of Mao's use of hyperbole, another being his casual acceptance of death of half the population during a nuclear war. In other contexts, Mao did not in fact accept mass death. Zhou's Chronology shows that in October 1958, Mao expressed real concern that 40,000 people in Yunnan had starved to death (p. 173). Shortly after the March 25 meeting, he worried about 25.2 million people who were at risk of starvation. But from late summer on, Mao essentially forgot about this issue, until, as noted, the "Xinyang Incident" came to light in October 1960.

Early in the Great Leap Forward, commune members were encouraged to eat their fill in communal canteens, and later many canteens shut down as they ran out of food and fuel.

In the article "Mao Zedong and the Famine of 1959–1960: A Study in Wilfulness", published in 2006 in The China Quarterly, Professor Thomas P. Bernstein also discussed Mao's change of attitudes during different phases of the Great Leap Forward:

In late autumn 1958, Mao Zedong strongly condemned widespread practices of the Great Leap Forward (GLF) such as subjecting peasants to exhausting labour without adequate food and rest, which had resulted in epidemics, starvation and deaths. At that time Mao explicitly recognized that anti-rightist pressures on officialdom were a major cause of "production at the expense of livelihood." While he was not willing to acknowledge that only abandonment of the GLF could solve these problems, he did strongly demand that they be addressed. After the July 1959 clash at Lushan with Peng Dehuai, Mao revived the GLF in the context of a new, extremely harsh anti-rightist campaign, which he relentlessly promoted into the spring of 1960 together with the radical policies that he previously condemned. Not until spring 1960 did Mao again express concern about abnormal deaths and other abuses, but he failed to apply the pressure needed to stop them. Given what he had already learned about the costs to the peasants of GLF extremism, the Chairman should have known that the revival of GLF radicalism would exact a similar or even bigger price. Instead, he wilfully ignored the lessons of the first radical phase for the sake of achieving extreme ideological and developmental goals.

In Hungry Ghosts: Mao's Secret Famine, Jasper Becker

notes that Mao was dismissive of reports he received of food shortages

in the countryside and refused to change course, believing that peasants

were lying and that rightists and kulaks were hoarding grain. He refused to open state granaries, and instead launched a series of "anti-grain concealment" drives that resulted in numerous purges and suicides.

Other violent campaigns followed in which party leaders went from

village to village in search of hidden food reserves, and not only

grain, as Mao issued quotas for pigs, chickens, ducks and eggs. Many

peasants accused of hiding food were tortured and beaten to death.

Whatever the cause of the disaster, Mao lost esteem among many of

the top party cadres. He was eventually forced to abandon the policy in

1962, and he lost political power to moderate leaders such as Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping.

Mao, however, supported by national propaganda, claimed that he was

only partly to blame for the famine. As a result, he was able to remain

Chairman of the Communist Party, with the Presidency transferred to Liu

Shaoqi.

The Great Leap Forward was a tragedy for the vast majority of the

Chinese. Although the steel quotas were officially reached, almost all

of the supposed steel made in the countryside was iron, as it had been

made from assorted scrap metal in home-made furnaces with no reliable

source of fuel such as coal. This meant that proper smelting

conditions could not be achieved. According to Zhang Rongmei, a

geometry teacher in rural Shanghai during the Great Leap Forward:

We took all the furniture, pots, and pans we had in our house, and all our neighbours did likewise. We put everything in a big fire and melted down all the metal.

The worst of the famine was steered towards enemies of the state. As Jasper Becker explains:

The most vulnerable section of China's population, around five per cent, were those whom Mao called 'enemies of the people'. Anyone who had in previous campaigns of repression been labeled a 'black element' was given the lowest priority in the allocation of food. Landlords, rich peasants, former members of the nationalist regime, religious leaders, rightists, counter-revolutionaries and the families of such individuals died in the greatest numbers.

At a large Communist Party conference in Beijing in January 1962,

called the "Conference of the Seven Thousand", State Chairman Liu Shaoqi

denounced the Great Leap Forward as responsible for widespread famine. The overwhelming majority of delegates expressed agreement, but Defense Minister Lin Biao staunchly defended Mao. A brief period of liberalization followed while Mao and Lin plotted a comeback. Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping

rescued the economy by disbanding the people's communes, introducing

elements of private control of peasant smallholdings and importing grain

from Canada and Australia to mitigate the worst effects of famine.

Consequences

Mao with Henry Kissinger and Zhou Enlai, Beijing, 1972

At the Lushan Conference

in July/August 1959, several ministers expressed concern that the Great

Leap Forward had not proved as successful as planned. The most direct

of these was Minister of Defence and Korean War veteran General Peng Dehuai.

Following Peng's criticism of the Great Leap Forward, Mao orchestrated a

purge of Peng and his supporters, stifling criticism of the Great Leap

policies. Senior officials who reported the truth of the famine to Mao

were branded as "right opportunists."

A campaign against right-wing opportunism was launched and resulted in

party members and ordinary peasants being sent to prison labor camps

where many would subsequently die in the famine. Years later the CPC

would conclude that as many as six million people were wrongly punished

in the campaign.

The number of deaths by starvation during the Great Leap Forward

is deeply controversial. Until the mid-1980s, when official census

figures were finally published by the Chinese Government, little was

known about the scale of the disaster in the Chinese countryside, as the

handful of Western observers allowed access during this time had been

restricted to model villages where they were deceived into believing

that the Great Leap Forward had been a great success. There was also an

assumption that the flow of individual reports of starvation that had

been reaching the West, primarily through Hong Kong and Taiwan, must

have been localised or exaggerated as China was continuing to claim

record harvests and was a net exporter of grain through the period.

Because Mao wanted to pay back early to the Soviets debts totalling

1.973 billion yuan from 1960 to 1962, exports increased by 50%, and fellow Communist regimes in North Korea, North Vietnam and Albania were provided grain free of charge.

Censuses were carried out in China in 1953, 1964 and 1982. The

first attempt to analyse this data to estimate the number of famine

deaths was carried out by American demographer Dr. Judith Banister and

published in 1984. Given the lengthy gaps between the censuses and

doubts over the reliability of the data, an accurate figure is difficult

to ascertain. Nevertheless, Banister concluded that the official data

implied that around 15 million excess deaths incurred in China during

1958–61, and that based on her modelling of Chinese demographics during

the period and taking account of assumed under-reporting during the

famine years, the figure was around 30 million. The official statistic

is 20 million deaths, as given by Hu Yaobang. Yang Jisheng, a former Xinhua News Agency reporter who had privileged access and connections available to no other scholars, estimates a death toll of 36 million.

Frank Dikötter estimates that there were at least 45 million premature

deaths attributable to the Great Leap Forward from 1958 to 1962. Various other sources have put the figure at between 20 and 46 million.

Split from Soviet Union

U.S. President Gerald Ford watches as Henry Kissinger shakes hands with Mao during their visit to China, December 2, 1975

On the international front, the period was dominated by the further isolation of China. The Sino-Soviet split resulted in Nikita Khrushchev's withdrawal of all Soviet technical experts and aid from the country. The split concerned the leadership of world communism.

The USSR had a network of Communist parties it supported; China now

created its own rival network to battle it out for local control of the

left in numerous countries. Lorenz M. Lüthi argues:

The Sino-Soviet split was one of the key events of the Cold War, equal in importance to the construction of the Berlin Wall, the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Second Vietnam War, and Sino-American rapprochement. The split helped to determine the framework of the Second Cold War in general, and influenced the course of the Second Vietnam War in particular.

The split resulted from Nikita Khrushchev's more moderate Soviet leadership after the death of Stalin in March 1953. Only Albania

openly sided with China, thereby forming an alliance between the two

countries which would last until after Mao's death in 1976. Warned that

the Soviets had nuclear weapons, Mao minimized the threat. Becker says

that "Mao believed that the bomb was a 'paper tiger', declaring to

Khrushchev that it would not matter if China lost 300 million people in a

nuclear war: the other half of the population would survive to ensure

victory".

Stalin had established himself as the successor of "correct" Marxist thought well before Mao controlled the Communist Party of China,

and therefore Mao never challenged the suitability of any Stalinist

doctrine (at least while Stalin was alive). Upon the death of Stalin,

Mao believed (perhaps because of seniority) that the leadership of

Marxist doctrine would fall to him. The resulting tension between

Khrushchev (at the head of a politically and militarily superior

government), and Mao (believing he had a superior understanding of

Marxist ideology) eroded the previous patron-client relationship between

the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and the CPC.

In China, the formerly favoured Soviets were now denounced as

"revisionists" and listed alongside "American imperialism" as movements

to oppose.

Partly surrounded by hostile American military bases (in South Korea, Japan, and Taiwan), China was now confronted with a new Soviet

threat from the north and west. Both the internal crisis and the

external threat called for extraordinary statesmanship from Mao, but as

China entered the new decade the statesmen of the People's Republic were

in hostile confrontation with each other.

Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution

During the early 1960s, Mao became concerned with the nature of

post-1959 China. He saw that the revolution and Great Leap Forward had

replaced the old ruling elite with a new one. He was concerned that

those in power were becoming estranged from the people they were to

serve. Mao believed that a revolution of culture would unseat and

unsettle the "ruling class" and keep China in a state of "perpetual

revolution" that, theoretically, would serve the interests of the

majority, rather than a tiny and privileged elite. State Chairman Liu Shaoqi and General Secretary Deng Xiaoping

favoured the idea that Mao be removed from actual power as China's head

of state and government but maintain his ceremonial and symbolic role

as Chairman of the Communist Party of China, with the party upholding

all of his positive contributions to the revolution. They attempted to

marginalise Mao by taking control of economic policy and asserting

themselves politically as well. Many claim that Mao responded to Liu and

Deng's movements by launching the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution in 1966. Some scholars, such as Mobo Gao, claim the case for this is overstated. Others, such as Frank Dikötter,

hold that Mao launched the Cultural Revolution to wreak revenge on

those who had dared to challenge him over the Great Leap Forward.

Believing that certain liberal bourgeois elements of society

continued to threaten the socialist framework, groups of young people

known as the Red Guards

struggled against authorities at all levels of society and even set up

their own tribunals. Chaos reigned in much of the nation, and millions

were persecuted. During the Cultural Revolution, nearly all of the

schools and universities in China were closed, and the young

intellectuals living in cities were ordered to the countryside to be

"re-educated" by the peasants, where they performed hard manual labour

and other work.

The Cultural Revolution led to the destruction of much of China's

traditional cultural heritage and the imprisonment of a huge number of

Chinese citizens, as well as the creation of general economic and social

chaos in the country. Millions of lives were ruined during this period,

as the Cultural Revolution pierced into every part of Chinese life,

depicted by such Chinese films as To Live, The Blue Kite and Farewell My Concubine. It is estimated that hundreds of thousands of people, perhaps millions, perished in the violence of the Cultural Revolution.

When Mao was informed of such losses, particularly that people

had been driven to suicide, he is alleged to have commented: "People who

try to commit suicide—don't attempt to save them! . . . China is such a

populous nation, it is not as if we cannot do without a few people." The authorities allowed the Red Guards to abuse and kill opponents of the regime. Said Xie Fuzhi,

national police chief: "Don't say it is wrong of them to beat up bad

persons: if in anger they beat someone to death, then so be it." As a result, in August and September 1966, there were a reported 1,772 people murdered by the Red Guards in Beijing alone.

It was during this period that Mao chose Lin Biao,

who seemed to echo all of Mao's ideas, to become his successor. Lin was

later officially named as Mao's successor. By 1971, however, a divide

between the two men had become apparent. Official history in China

states that Lin was planning a military coup or an assassination attempt

on Mao. Lin Biao died in a plane crash over the air space of Mongolia,

presumably as he fled China, probably anticipating his arrest. The CPC

declared that Lin was planning to depose Mao and posthumously expelled

Lin from the party. At this time, Mao lost trust in many of the top CPC

figures. The highest-ranking Soviet Bloc intelligence defector, Lt. Gen.

Ion Mihai Pacepa described his conversation with Nicolae Ceaușescu, who told him about a plot to kill Mao Zedong with the help of Lin Biao organised by the KGB.

Despite being considered a feminist figure by some and a supporter of women's rights, documents released by the US Department of State

in 2008 show that Mao declared women to be a "nonsense" in 1973, in

conversation with Kissinger, joking that "China is a very poor country.

We don't have much. What we have in excess is women... Let them go to

your place. They will create disasters. That way you can lessen our

burdens." When Mao offered 10 million women, Kissinger replied by saying that Mao was "improving his offer".

Mao and Kissinger then agreed that their comments on women be removed

from public records, prompted by a Chinese official who feared that

Mao's comments might incur public anger if released.

"Mango fever"

When Mao first tasted mangoes in 1968 he was enthused, describing them as a "spiritual time bomb".

News of his enthusiasm made it to the Pakistani foreign office, and on

August 4, 1968, Mao was presented with about 40 mangoes by the Pakistani foreign minister, Syed Sharifuddin Pirzada, in an apparent diplomatic gesture. Mao had his aide send the box of mangoes to his Mao Zedong Propaganda Team at Tsinghua University on August 5, the team stationed there to quiet strife among Red Guard factions. On August 7, an article was published in the People's Daily saying:

In the afternoon of the fifth, when the great happy news of Chairman Mao giving mangoes to the Capital Worker and Peasant Mao Zedong Thought Propaganda Team reached the Tsinghua University campus, people immediately gathered around the gift given by the Great Leader Chairman Mao. They cried out enthusiastically and sang with wild abandonment. Tears swelled up in their eyes, and they again and again sincerely wished that our most beloved Great Leader lived then thousand years without bounds ... They all made phone calls to their own work units to spread this happy news; and they also organised all kinds of celebratory activities all night long, and arrived at [the national leadership compound] Zhongnanhai despite the rain to report the good news, and to express their loyalty to the Great Leader Chairman Mao.

Subsequent articles were also written by government officials propagandizing the reception of the mangoes, and another poem in the People's Daily

said: "Seeing that golden mango/Was as if seeing the great leader

Chairman Mao ... Again and again touching that golden mango/the golden

mango was so warm".

Few people at this time in China had ever seen a mango before, and a

mango was seen as "a fruit of extreme rarity, like Mushrooms of

Immortality".

Mangoes, The Precious Gift ... (poster, 1968)

One of the mangoes was sent to the Beijing Textile Factory, whose revolutionary committee organised a rally in the mangoes' honour.

Workers read out quotations from Mao and celebrated the gift. Altars

were erected to prominently display the fruit; when the mango peel began

to rot after a few days, the fruit was peeled and boiled in a pot of

water. Workers then filed by and each was given a spoonful of mango

water. The revolutionary committee also made a wax replica of the mango,

and displayed this as a centrepiece in the factory. There followed

several months of "mango fever", as the fruit became a focus of a

"boundless loyalty" campaign for Chairman Mao. More replica mangoes were

created and the replicas were sent on tour around Beijing and elsewhere

in China. Many revolutionary committees visited the mangoes in Beijing

from outlying provinces; approximately half a million people greeted the

replicas when they arrived in Chengdu. Badges and wall posters featuring the mangoes and Mao were produced in the millions.

The fruit was shared among all institutions that had been a part of the

propaganda team, and large processions were organised in support of the

zhengui lipin ("precious gift"), as the mangoes were known as.

One dentist in a small town, Dr. Han, saw the mango and said it was

nothing special and looked just like a sweet potato; he was put on trial

for malicious slander, found guilty, paraded publicly throughout the

town, and then executed with one shot to the head.

It has been claimed that Mao used the mangoes to express support

for the workers who would go to whatever lengths necessary to end the

factional fighting among students, and a "prime example of Mao's

strategy of symbolic support". Even up until early 1969, participants of Mao Zedong Thought study classes in Beijing would return with mass-produced mango facsimiles and still gain media attention in the provinces.

End of the Cultural Revolution

In 1969, Mao declared the Cultural Revolution to be over, although

various historians in and outside of China mark the end of the Cultural

Revolution—as a whole or in part—in 1976, following Mao's death and the

arrest of the Gang of Four. In the last years of his life, Mao was faced with declining health due to either Parkinson's disease or, according to his physician, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, as well as lung ailments due to smoking and heart trouble.

Some also attributed Mao's decline in health to the betrayal of Lin

Biao. Mao remained passive as various factions within the Communist

Party mobilised for the power struggle anticipated after his death.

The Cultural Revolution is often looked at in all scholarly

circles as a greatly disruptive period for China. While one-tenth of

Chinese people—an estimated 100 million—did suffer during the period,

some scholars, such as Lee Feigon and Mobo Gao, claim there were many

great advances, and in some sectors the Chinese economy continued to

outperform the West.

They hold that the Cultural Revolution period laid the foundation for

the spectacular growth that continues in China. During the Cultural

Revolution, China detonated its first H-Bomb (1967), launched the Dong Fang Hong

satellite (January 30, 1970), commissioned its first nuclear submarines

and made various advances in science and technology. Healthcare was

free, and living standards in the countryside continued to improve.

In comparison, the Great Leap probably did cause a much larger loss of

life with its flawed economic policies which encompassed even the

peasants.

Estimates of the death toll during the Cultural Revolution,

including civilians and Red Guards, vary greatly. An estimate of around

400,000 deaths is a widely accepted minimum figure, according to Maurice Meisner.

MacFarquhar and Schoenhals assert that in rural China alone some

36 million people were persecuted, of whom between 750,000 and

1.5 million were killed, with roughly the same number permanently

injured. In Mao: The Unknown Story, Jung Chang and Jon Halliday claim that as many as 3 million people died in the violence of the Cultural Revolution.

Historian Daniel Leese notes that in the 1950s Mao's personality was hardening:

The impression of Mao's personality that emerges from the literature is disturbing. It reveals a certain temporal development from a down-to-earth leader, who was amicable when uncontested and occasionally reflected on the limits of his power, to an increasingly ruthless and self-indulgent dictator. Mao's preparedness to accept criticism decreased continuously.

State visits

During his leadership, Mao traveled outside China on only two

occasions, both state visits to the Soviet Union. When Mao stepped down

as head of state on April 27, 1959, further diplomatic state visits and

travels abroad were undertaken by president Liu Shaoqi rather than Mao personally.

Death and aftermath

Smoking may have played an important role in his declining health, for Mao was a heavy smoker during most of his adult life. It became a state secret that he suffered from multiple lung and heart ailments during his later years. There are unconfirmed reports that he possibly had Parkinson's disease in addition to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, also known as Lou Gehrig's disease.

Mao's last public appearance—and the last known photograph of him

alive—was on May 27, 1976, when he met the visiting Pakistani Prime

Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto during the latter's one-day visit to Beijing.

Mao suffered two major heart attacks in 1976, one in March and another

in July, before a third struck on September 5, rendering him an invalid.

Mao Zedong died nearly four days later just after midnight, at 00:10,

on September 9, 1976, at age 82. The Communist Party of China delayed