| Mediterranean Sea | |

|---|---|

Map of the Mediterranean Sea

| |

| Coordinates | 35°N 18°ECoordinates: 35°N 18°E |

| Type | Sea |

| Primary inflows | Atlantic Ocean, Sea of Marmara, Nile, Ebro, Rhône, Chelif, Po |

| Basin countries | about 60 |

| Surface area | 2,500,000 km2 (970,000 sq mi) |

|---|---|

| Average depth | 1,500 m (4,900 ft) |

| Max. depth | 5,267 m (17,280 ft) |

| Water volume | 3,750,000 km3 (900,000 cu mi) |

| Residence time | 80–100 years |

| Islands | 3300+ |

| Settlements | Alexandria, Algiers, Athens, Barcelona, Beirut, Carthage, Dubrovnik, Istanbul, İzmir, Rome, Split, Tangier, Tel Aviv, Tripoli, Tunis (full list) |

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa and on the east by the Levant. Although the sea is sometimes considered a part of the Atlantic Ocean, it is usually identified

as a separate body of water. Geological evidence indicates that around

5.9 million years ago, the Mediterranean was cut off from the Atlantic

and was partly or completely desiccated over a period of some 600,000

years, the Messinian salinity crisis, before being refilled by the Zanclean flood about 5.3 million years ago.

It covers an approximate area of 2.5 million km2 (965,000 sq mi), representing 0.7 % of the global ocean surface, but its connection to the Atlantic via the Strait of Gibraltar-the narrow strait that connects the Atlantic Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea and separates Spain in Europe from Morocco in Africa- is only 14 km (8.7 mi) wide. In oceanography, it is sometimes called the Eurafrican Mediterranean Sea or the European Mediterranean Sea to distinguish it from mediterranean seas elsewhere.

The Mediterranean Sea has an average depth of 1,500 m (4,900 ft) and the deepest recorded point is 5,267 m (17,280 ft) in the Calypso Deep in the Ionian Sea. The sea is bordered on the north by Europe, the east by Asia, and in the south by Africa. It is located between latitudes 30° and 46° N and longitudes 6° W and 36° E.

Its west-east length, from the Strait of Gibraltar to the Gulf of

Iskenderun, on the southwestern coast of Turkey, is approximately

4,000 km (2,500 miles). The sea's average north-south length, from

Croatia's southern shore

to Libya, is approximately 800 km (500 miles).

The sea was an important route for merchants and travellers of ancient times - it facilitated trade and cultural exchange between peoples of the region. The history of the Mediterranean region is crucial to understanding the origins and development of many modern societies.

The countries surrounding the Mediterranean in clockwise order are Spain, France, Monaco, Italy, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Albania, Greece, Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco; Malta and Cyprus are island countries in the sea. In addition, the Gaza Strip and the British Overseas Territories of Gibraltar and Akrotiri and Dhekelia have coastlines on the sea.

Names and etymology

With its highly indented coastline and large number of islands, Greece has the longest Mediterranean coastline.

The Ancient Greeks called the Mediterranean simply ἡ θάλασσα (hē thálassa; "the Sea") or sometimes ἡ μεγάλη θάλασσα (hē megálē thálassa; "the Great Sea"), ἡ ἡμέτερα θάλασσα (hē hēmétera thálassa; "Our Sea"), or ἡ θάλασσα ἡ καθ'ἡμᾶς (hē thálassa hē kath’hēmâs; "the sea around us").

The Romans called it Mare Magnum ("Great Sea") or Mare Internum ("Internal Sea") and, starting with the Roman Empire, Mare Nostrum ("Our Sea"). The term Mare Mediterrāneum appears later: Solinus apparently used it in the 3rd century, but the earliest extant witness to it is in the 6th century, in Isidore of Seville. It means 'in the middle of land, inland' in Latin, a compound of medius ("middle"), terra ("land, earth"), and -āneus ("having the nature of").

The Latin word is a calque of Greek μεσόγειος (mesógeios; "inland"), from μέσος (mésos, "in the middle") and γήινος (gḗinos, "of the earth"), from γῆ (gê,

"land, earth"). The original meaning may have been 'the sea in the

middle of the earth', rather than 'the sea enclosed by land'.

The Carthaginians called it the "Syrian Sea". In ancient Syrian texts, Phoenician epics and in the Hebrew Bible, it was primarily known as the "Great Sea" (הַיָּם הַגָּדוֹל, HaYam HaGadol, Numbers 34:6,7; Joshua 1:4, 9:1, 15:47; Ezekiel 47:10,15,20) or simply as "The Sea" (1 Kings 5:9; compare 1 Macc. 14:34, 15:11); however, it has also been called the "Hinder Sea" (הַיָּם הָאַחֲרוֹן) because of its location on the west coast of Greater Syria or the Holy Land (and therefore behind a person facing the east), which is sometimes translated as "Western Sea", (Deut. 11:24; Joel 2:20). Another name was the "Sea of the Philistines" (יָם פְּלִשְׁתִּים, Exod. 23:31), from the people inhabiting a large portion of its shores near the Israelites. In Modern Hebrew, it is called HaYam HaTikhon (הַיָּם הַתִּיכוֹן) 'the Middle Sea'.

In Modern Arabic, it is known as al-Baḥr [al-Abyaḍ] al-Mutawassiṭ (البحر [الأبيض] المتوسط) 'the [White] Middle Sea'. In Islamic and older Arabic literature, it was Baḥr al-Rūm(ī) (بحر الروم or بحر الرومي})

'the Sea of the Romans' or 'the Roman Sea'. At first, that name

referred to only the Eastern Mediterranean, but it was later extended to

the whole Mediterranean. Other Arabic names were Baḥr al-šām(ī) (بحر الشام) 'the Sea of Syria' and Baḥr al-Maghrib (بحرالمغرب) 'the Sea of the West'.

In Turkish, it is the Akdeniz 'the White Sea'; in Ottoman, ﺁق دكيز, which sometimes means only the Aegean Sea.

The origin of the name is not clear, as it is not known in earlier

Greek, Byzantine or Islamic sources. It may be to contrast with the Black Sea. In Persian, the name was translated as Baḥr-i Safīd, which was also used in later Ottoman Turkish. It is probably the origin of the colloquial Greek phrase Άσπρη Θάλασσα (Άspri Thálassa, lit. "White Sea").

Johann Knobloch claims that in Classical Antiquity, cultures in the Levant used colours to refer to the cardinal points: black referred to the north (explaining the name Black Sea), yellow or blue to east, red to south (i.e., the Red Sea), and white to west. This would explain both the Turkish Akdeniz (White Sea) and the Arab nomenclature described above.

History

Ancient civilizations

Greek (red) and Phoenician (yellow) colonies in antiquity c. the 6th century BCE

The Roman Empire at its farthest extent in AD 117

Several ancient civilizations were located around the Mediterranean

shores and were greatly influenced by their proximity to the sea. It

provided routes for trade, colonization, and war, as well as food (from

fishing and the gathering of other seafood) for numerous communities

throughout the ages.

Due to the shared climate, geology, and access to the sea,

cultures centered on the Mediterranean tended to have some extent of

intertwined culture and history.

Two of the most notable Mediterranean civilizations in classical antiquity were the Greek city states and the Phoenicians, both of which extensively colonized the coastlines of the Mediterranean. Later, when Augustus founded the Roman Empire, the Romans referred to the Mediterranean as Mare Nostrum

("Our Sea"). For the next 400 years, the Roman Empire completely

controlled the Mediterranean Sea and virtually all its coastal regions

from Gibraltar to the Levant.

Darius I of Persia, who conquered Ancient Egypt, built a canal linking the Mediterranean to the Red Sea. Darius's canal was wide enough for two triremes to pass each other with oars extended, and required four days to traverse.

Middle Ages and empires

The Battle of Lepanto, 1571, ended in victory for the European Holy League against the Ottoman Turks.

The Western Roman Empire collapsed around AD 476. Temporarily the east was again dominant as Roman power lived on in the Byzantine Empire formed in the 4th century from the eastern half of the Roman Empire. Another power arose in the 7th century, and with it the religion of Islam, which soon swept across from the east; at its greatest extent, the Arab Empire controlled 75% of the Mediterranean region and left a lasting footprint on its eastern and southern shores.

The Arab invasions disrupted the trade relations between Western

and Eastern Europe while cutting the trade route with Oriental lands.

This, however, had the indirect effect of promoting the trade across the

Caspian Sea. The export of grains from Egypt was re-routed towards the Eastern world. Oriental goods like silk and spices were carried from Egypt to ports like Venice and Constantinople by sailors and Jewish merchants. The Viking raids further disrupted the trade in western Europe and brought it to a halt. However, the Norsemen developed the trade from Norway to the White Sea, while also trading in luxury goods from Spain and the Mediterranean. The Byzantines in the mid-8th century

retook control of the area around the north-eastern part of the

Mediterranean. Venetian ships from the 9th century armed themselves to

counter the harassment by Arabs while concentrating trade of oriental

goods at Venice.

The Fatimids maintained trade relations with the Italian city-states like Amalfi and Genoa before the Crusades, according to the Cairo Geniza documents. A document dated 996 mentions Amalfian merchants living in Cairo. Another letter states that the Genoese had traded with Alexandria. The caliph al-Mustansir had allowed Amalfian merchants to reside in Jerusalem about 1060 in place of the Latin hospice.

The Crusades led to flourishing of trade between Europe and the outremer region. Genoa, Venica and Pisa

created colonies in regions controlled by the Crusaders and came to

control the trade with the Orient. These colonies also allowed them to

trade with the Eastern world. Though the fall of the Crusader states and

attempts at banning of trade relations with Muslim states by the Popes

temporarily disrupted the trade with the Orient, it however continued.

Europe started to revive, however, as more organized and centralized states began to form in the later Middle Ages after the Renaissance of the 12th century.

The bombardment of Algiers by the Anglo-Dutch fleet in support of an ultimatum to release European slaves, August 1816

Ottoman power based in Anatolia continued to grow, and in 1453 extinguished the Byzantine Empire with the Conquest of Constantinople. Ottomans gained control of much of the sea in the 16th century and maintained naval bases in southern France (1543–1544), Algeria and Tunisia. Barbarossa, the famous Ottoman captain is a symbol of this domination with the victory of the Battle of Preveza (1538). The Battle of Djerba

(1560) marked the apex of Ottoman naval domination in the

Mediterranean. As the naval prowess of the European powers increased,

they confronted Ottoman expansion in the region when the Battle of Lepanto (1571) checked the power of the Ottoman Navy. This was the last naval battle to be fought primarily between galleys.

The Barbary pirates of Northwest Africa preyed on Christian shipping and coastlines in the Western Mediterranean Sea. According to Robert Davis, from the 16th to 19th centuries, pirates captured 1 million to 1.25 million Europeans as slaves.

The development of oceanic shipping began to affect the entire

Mediterranean. Once, most trade between Western Europe and the East had

passed through the region, but after the 1490s the development of a sea

route to the Indian Ocean allowed the importation of Asian spices and other goods through the Atlantic ports of western Europe.

The sea remained strategically important. British mastery of Gibraltar ensured their influence in Africa and Southwest Asia. Wars included Naval warfare in the Mediterranean during World War I and Mediterranean theatre of World War II.

21st century and migrations

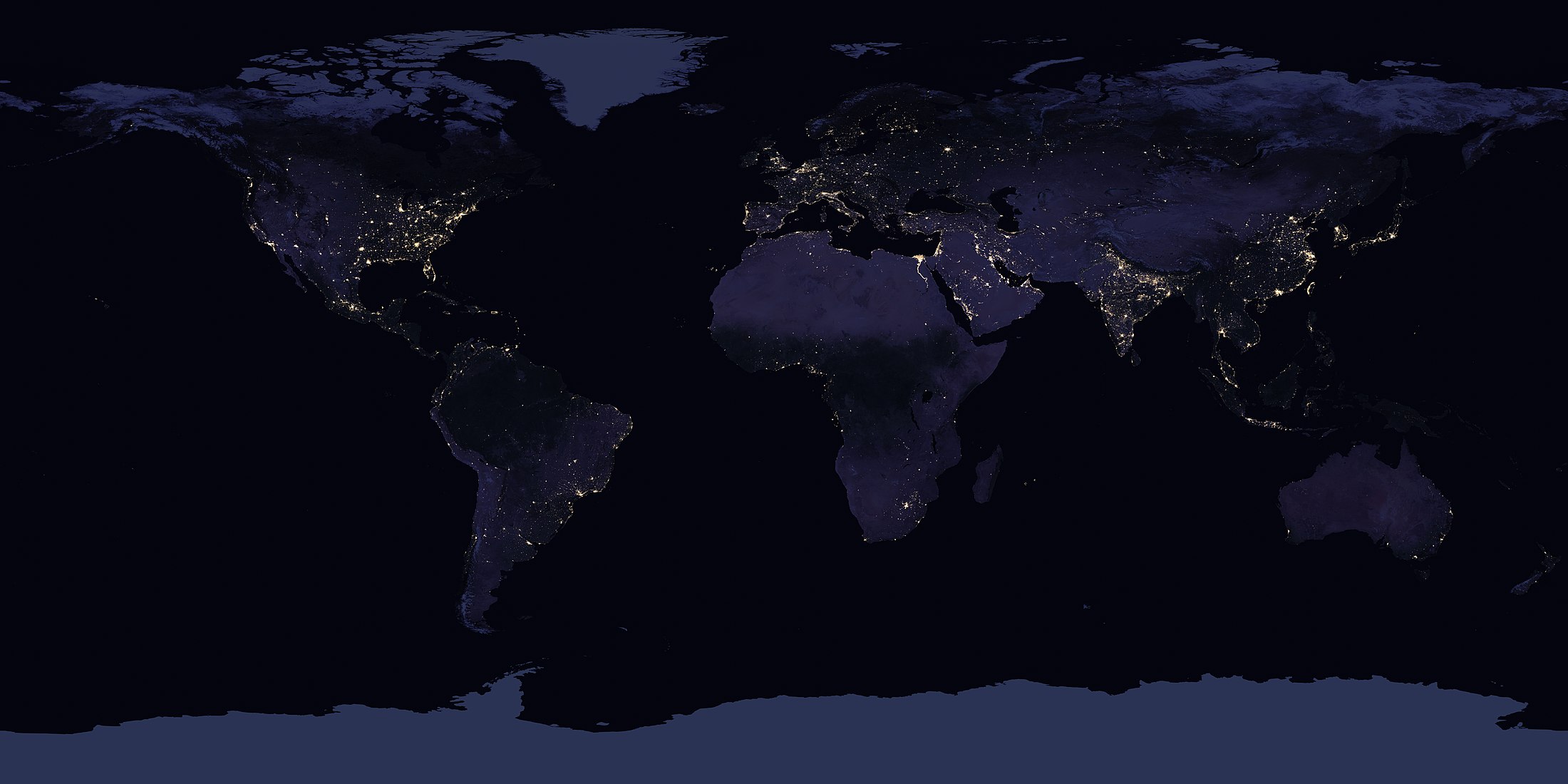

Satellite image of the Mediterranean Sea at night

In 2013 the Maltese president described the Mediterranean sea as a

"cemetery" due to the large number of migrants who drowned there after

their boats capsized. European Parliament president Martin Schulz

said in 2014 that Europe's migration policy "turned the Mediterranean

into a graveyard", referring to the number of drowned refugees in the

region as a direct result of the policies. An Azerbaijani official described the sea as "a burial ground ... where people die".

Following the 2013 Lampedusa migrant shipwreck, the Italian government decided to strengthen the national system for the patrolling of the Mediterranean Sea by authorising "Operation Mare Nostrum",

a military and humanitarian mission in order to rescue the migrants and

arrest the traffickers of immigrants. In 2015, more than one million

migrants crossed the Mediterranean Sea into Europe.

Italy was particularly affected by the European migrant crisis. Since 2013, over 700,000 migrants have landed in Italy, mainly sub-Saharan Africans.

Geography

A satellite image showing the Mediterranean Sea. The Strait of Gibraltar can be seen in the bottom left (north-west) quarter of the image; to its left is the Iberian Peninsula in Europe, and to its right, the Maghreb in Africa.

The Dardanelles strait in Turkey. The north side is Europe with the Gelibolu Peninsula in the Thrace region; the south side is Anatolia in Asia.

The Mediterranean Sea is connected to the Atlantic Ocean by the Strait of Gibraltar (known in Homer's writings as the "Pillars of Hercules") in the west and to the Sea of Marmara and the Black Sea, by the Dardanelles and the Bosporus respectively, in the east. The Sea of Marmara (Dardanelles)

is often considered a part of the Mediterranean Sea, whereas the Black

Sea is generally not. The 163 km (101 mi) long artificial Suez Canal in the southeast connects the Mediterranean Sea to the Red Sea.

Large islands in the Mediterranean include Cyprus, Crete, Euboea, Rhodes, Lesbos, Chios, Kefalonia, Corfu, Limnos, Samos, Naxos and Andros in the Eastern Mediterranean; Sicily, Cres, Krk, Brač, Hvar, Pag, Korčula and Malta in the central Mediterranean; Sardinia, Corsica, and the Balearic Islands: Ibiza, Majorca, and Menorca in the Western Mediterranean.

The typical Mediterranean climate has hot, humid, and dry summers and mild, rainy winters. Crops of the region include olives, grapes, oranges, tangerines, and cork.

Extent

The International Hydrographic Organization defines the limits of the Mediterranean Sea as follows:

Stretching from the Strait of Gibraltar in the west to the entrances to the Dardanelles and the Suez Canal in the east, the Mediterranean Sea is bounded by the coasts of Europe, Africa and Asia, and is divided into two deep basins:

- Western Basin:

- On the west: A line joining the extremities of Cape Trafalgar (Spain) and Cape Spartel (Africa).

- On the northeast: The west coast of Italy. In the Strait of Messina a line joining the north extreme of Cape Paci (15°42'E) with Cape Peloro, the east extreme of the Island of Sicily. The north coast of Sicily.

- On the east: A line joining Cape Lilibeo the western point of Sicily (37°47′N 12°22′E), through the Adventure Bank to Cape Bon (Tunisia).

- Eastern Basin:

- On the west: The northeastern and eastern limits of the Western Basin.

- On the northeast: A line joining Kum Kale (26°11'E) and Cape Helles, the western entrance to the Dardanelles.

- On the southeast: The entrance to the Suez Canal.

- On the east: The coasts of Syria and Israel.

Coastal countries

Map of the Mediterranean Sea

The following countries have a coastline on the Mediterranean Sea:

- Northern shore (from west to east): Spain, France, Monaco, Italy, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro, Albania, Greece, Turkey.

- Eastern shore (from north to south): Turkey, Syria, Lebanon, Israel, Egypt.

- Southern shore (from west to east): Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia, Libya, Egypt.

- Island nations: Malta, Cyprus.

Several other territories also border the Mediterranean Sea (from west to east): The British overseas territory of Gibraltar, the Spanish autonomous cities of Ceuta and Melilla and nearby islands, the Sovereign Base Areas on Cyprus, and the Palestinian Gaza Strip.

Barcelona, the third largest metropolitan area on the Mediterranean Sea (after Istanbul and Alexandria) and also the headquarters of the Union for the Mediterranean

The Acropolis of Athens with the Mediterranean Sea in the background

The ancient port of Jaffa (now part of Tel Aviv-Yafo) in Israel: according to the Bible, where Jonah set sail before being swallowed by a whale

Alexandria, the second largest city on the Mediterranean after Istanbul, Turkey

Catania, Sicily, with Mount Etna in the background

Coastal cities

Major cities (municipalities) with populations larger than 200,000 people bordering the Mediterranean Sea are:

| Country | Cities |

|---|---|

| Algeria | Algiers, Annaba, Oran |

| Egypt | Alexandria, Damietta, Port Said |

| France | Marseille, Nice |

| Greece | Athens, Piraeus, Patras, Thessaloniki |

| Israel | Ashdod, Haifa, Netanya, Rishon LeZion, Tel Aviv |

| Italy | Bari, Catania, Genoa, Messina, Naples, Palermo, Rome, Taranto, Trieste, Venice |

| Lebanon | Beirut, Tripoli |

| Libya | Benghazi, Khoms, Misrata, Tripoli, Zawiya, Zliten |

| Morocco | Tétouan, Tangier |

| Palestine | Gaza City, Khan Yunis |

| Spain | Alicante, Badalona, Barcelona, Cartagena, Málaga, Palma, Valencia. |

| Syria | Latakia |

| Tunisia | Sfax, Sousse, Tunis |

| Turkey | Adana, Antalya, Istanbul (through the Sea of Marmara), İzmir, Mersin |

Subdivisions

Africa (left, on horizon) and Europe (right), as seen from Gibraltar

The International Hydrographic Organization (IHO) divides the Mediterranean into a number of smaller waterbodies, each with their own designation (from west to east):

- The Strait of Gibraltar;

- The Alboran Sea, between Spain and Morocco;

- The Balearic Sea, between mainland Spain and its Balearic Islands;

- The Ligurian Sea between Corsica and Liguria (Italy);

- The Tyrrhenian Sea enclosed by Sardinia, Italian peninsula and Sicily;

- The Ionian Sea between Italy, Albania and Greece;

- The Adriatic Sea between Italy, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina, Montenegro and Albania;

- The Aegean Sea between Greece and Turkey.

Other seas

Some other seas whose names have been in common use from the ancient times, or in the present:

- The Sea of Sardinia, between Sardinia and Balearic Islands, as a part of the Balearic Sea;

- The Sea of Sicily between Sicily and Tunisia;

- The Libyan Sea between Libya and Crete;

- In the Aegean Sea;

- The Thracian Sea in its north;

- The Myrtoan Sea between the Cyclades and the Peloponnese;

- The Sea of Crete north of Crete;

- The Icarian Sea between Kos and Chios;

- The Cilician Sea between Turkey and Cyprus;

- The Levantine Sea at the eastern end of the Mediterranean.

Many of these smaller seas feature in local myth and folklore and derive their names from these associations.

Other features

View of the Saint George Bay, and snow-capped Mount Sannine from the Corniche, Beirut

The Port of Marseille seen from L'Estaque

Sarandë, Albania is situated on an open sea gulf of the Ionian sea in the central Mediterranean.

- The Saint George Bay in Beirut, Lebanon;

- The Ras Ibn Hani cape in Latakia, Syria;

- The Ras al-Bassit cape in northern Syria;

- The Minet el-Beida ("White Harbour") bay near ancient Ugarit, Syria;

- The Strait of Gibraltar, connects the Atlantic Ocean to the Mediterranean Sea and separates Spain from Morocco;

- The Bay of Gibraltar, at the southern end of the Iberian Peninsula;

- The Gulf of Corinth, an enclosed sea between the Ionian Sea and the Corinth Canal;

- The Pagasetic Gulf, the gulf of Volos, south of the Thermaic Gulf, formed by the Mount Pelion peninsula;

- The Saronic Gulf, the gulf of Athens, between the Corinth Canal and the Mirtoan Sea;

- The Thermaic Gulf, the gulf of Thessaloniki, located in the northern Greek region of Macedonia;

- The Kvarner Gulf, Croatia;

- The Gulf of Lion, south of France;

- The Gulf of Valencia, east of Spain;

- The Strait of Messina, between Sicily and Calabrian peninsula;

- The Gulf of Genoa, northwestern Italy;

- The Gulf of Venice, northeastern Italy;

- The Gulf of Trieste, northeastern Italy;

- The Gulf of Taranto, southern Italy;

- The Paklinski Islands off the coast of Croatia; the Adriatic Sea contains over 1200 islands and islets;

- The Gulf of Salerno, southwestern Italy;

- The Gulf of Gaeta, southwestern Italy;

- The Gulf of Squillace, southern Italy;

- The Strait of Otranto, between Italy and Albania;

- The Gulf of Haifa, northern Israel;

- The Gulf of Sidra, between Tripolitania (western Libya) and Cyrenaica (eastern Libya);

- The Strait of Sicily, between Sicily and Tunisia;

- The Corsica Channel, between Corsica and Italy;

- The Strait of Bonifacio, between Sardinia and Corsica;

- The Gulf of İskenderun, between İskenderun and Adana (Turkey);

- The Gulf of Antalya, between west and east shores of Antalya (Turkey);

- The Bay of Kotor, in south-western Montenegro and south-eastern Croatia;

- The Malta Channel, between Sicily and Malta;

- The Gozo Channel, between Malta Island and Gozo.

Ten largest islands by area

| Country | Island | Area in km2 | Population |

|---|---|---|---|

| Italy | Sicily | 25,460 | 5,048,995 |

| Italy | Sardinia | 23,821 | 1,672,804 |

| Cyprus | Cyprus | 9,251 | 1,088,503 |

| France | Corsica | 8,680 | 299,209 |

| Greece | Crete | 8,336 | 623,666 |

| Greece | Euboea | 3,655 | 218.000 |

| Spain | Majorca | 3,640 | 869,067 |

| Greece | Lesbos | 1,632 | 90,643 |

| Greece | Rhodes | 1,400 | 117,007 |

| Greece | Chios | 842 | 51,936 |

Climate

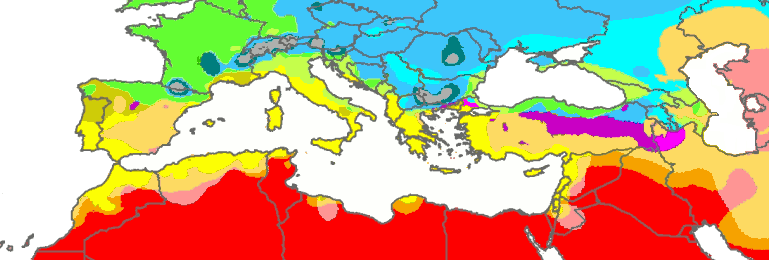

Much of the Mediterranean coast enjoys a hot-summer Mediterranean climate. However, most of its southeastern coast has a hot desert climate, and much of Spain's eastern (Mediterranean) coast has a cold semi-arid climate. Although they are rare, tropical cyclones occasionally form in the Mediterranean Sea, typically in September–November.

Sea temperature

|

|

Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Marseille | 13 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 16 | 18 | 21 | 22 | 21 | 18 | 16 | 14 | 16.6 |

| Gibraltar | 16 | 15 | 16 | 16 | 17 | 20 | 22 | 22 | 22 | 20 | 18 | 17 | 18.4 |

| Málaga | 16 | 15 | 15 | 16 | 17 | 20 | 22 | 23 | 22 | 20 | 18 | 16 | 18.3 |

| Athens | 16 | 15 | 15 | 16 | 18 | 21 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 21 | 19 | 18 | 19.3 |

| Barcelona | 13 | 13 | 13 | 14 | 17 | 20 | 23 | 25 | 23 | 20 | 17 | 15 | 17.8 |

| Heraklion | 16 | 15 | 15 | 16 | 19 | 22 | 24 | 25 | 24 | 22 | 20 | 18 | 19.7 |

| Venice | 11 | 10 | 11 | 13 | 18 | 22 | 25 | 26 | 23 | 20 | 16 | 14 | 17.4 |

| Valencia | 14 | 13 | 14 | 15 | 17 | 21 | 24 | 26 | 24 | 21 | 18 | 15 | 18.5 |

| Malta | 16 | 16 | 15 | 16 | 18 | 21 | 24 | 26 | 25 | 23 | 21 | 18 | 19.9 |

| Alexandria | 18 | 17 | 17 | 18 | 20 | 23 | 25 | 26 | 26 | 25 | 22 | 20 | 21.4 |

| Naples | 15 | 14 | 14 | 15 | 18 | 22 | 25 | 27 | 25 | 22 | 19 | 16 | 19.3 |

| Larnaca | 18 | 17 | 17 | 18 | 20 | 24 | 26 | 27 | 27 | 25 | 22 | 19 | 21.7 |

| Limassol | 18 | 17 | 17 | 18 | 20 | 24 | 26 | 27 | 27 | 25 | 22 | 19 | 21.7 |

| Antalya | 17 | 17 | 17 | 18 | 21 | 24 | 27 | 28 | 27 | 25 | 22 | 19 | 21.8 |

| Tel Aviv | 18 | 17 | 17 | 18 | 21 | 24 | 26 | 28 | 27 | 26 | 23 | 20 | 22.1 |

Oceanography

Predominant surface currents for June

Being nearly landlocked affects conditions in the Mediterranean Sea: for instance, tides

are very limited as a result of the narrow connection with the Atlantic

Ocean. The Mediterranean is characterised and immediately recognised by

its deep blue colour.

Evaporation greatly exceeds precipitation and river runoff in the Mediterranean, a fact that is central to the water circulation within the basin. Evaporation is especially high in its eastern half, causing the water level to decrease and salinity to increase eastward. The average salinity in the basin is 38 PSU at 5 m depth.

The temperature of the water in the deepest part of the Mediterranean Sea is 13.2 °C (55.8 °F).

General circulation

Water circulation in the Mediterranean can be described from the surface waters entering from the Atlantic through the Strait of Gibraltar.

These cool and relatively low-salinity waters circulate westwards along

the North African coasts. A part of these surface waters does not pass

the Strait of Sicily, but deviates towards Corsica

before exiting the Mediterranean. The surface waters entering the

eastern Mediterranean basin circulate along the Lybian and Israelian

coasts. Upon reaching the Levantine Sea,

the surface waters having experienced warming and saltening from their

initial Atlantic state, are now more dense and deepen to form the

Levantine Intermediate Waters (LIW). Most of the water found anywhere

between 50 and 600 m deep in the Mediterranean originates from the LIW.

LIW are formed along the coasts of Turkey and circulate eastwards along

the Greek and South Italian coasts. LIW are the only waters passing the

Sicily Strait eastwards. After the Strait of Sicily, the intermediate

waters circulate along the Italian, French and Spanish coasts before

exiting the Mediterranean through the depths of the Strait of Gibraltar.

Deep water in the Mediterranean originates from three main areas: the Adriatic Sea, from which most of the deep water in the eastern Mediterranean originates, the Aegean Sea, and the Gulf of Lion. Deep water formation in the Mediterranean is triggered by strong winter convection fueled by intense cold winds like the Bora.

When new deep water is formed, the older waters mix with the overlaying

intermediate waters and eventually exit the Mediterranean. The

residence time of water in the Mediterranean is approximately 100 years,

making the Mediterranean especially sensitive to climate change.

Other events affecting water circulation

Being

a semi-enclosed basin, the Mediterranean experiences transitory events

that can affect the water circulation on short time scales. In the Mid

1990s, the Aegean Sea became the main area for deep water formation in

the eastern Mediterranean after particularly cold winter conditions.

This transitory switch in the origin of deep waters in the eastern

Mediterranean was termed Eastern Mediterranean Transient (EMT) and had

major consequences on water circulation of the Mediterranean.

Another example of a transient event affecting the Mediterranean

circulation is the periodic inversion of the North Ionian Gyre, which is

an anticyclonic ocean gyre observed in the northern part of the Ionian Sea,

off the Greek coast. The transition from anticylonic to cyclonic

rotation of this gyre changes the origin of the waters fueling it; when

the circulation is anticyclonic (most common), the waters of the gyre

originate from the Adriatic Sea. When the circulation is cyclonic, the

waters originate from the Levantine Sea.

These waters have different physical and chemical characteristics, and

the periodic inversion of the North Ionian Gyre (called Bimodal

Oscillating System or BiOS) changes the Mediterranean circulation and

biogeochemistry around the Adriatic and Levantine regions.

Climate change

Because of the short residence time of waters, the Mediterranean Sea is considered a hot-spot for climate change effects. Deep water temperatures have increased by 0.12°C between 1959 and 1989.

According to climate projections, the Mediterranean Sea could become

warmer. The decrease in precipitation over the region could lead to more

evaporation ultimately increasing the Mediterranean Sea salinity. Because of the changes in temperature and salinity, the Mediterranean

Sea may become more stratified by the end of the 21st century, with

notable consequences on water circulation and biogeochemistry.

Biogeochemistry

In

spite of its great biodiversity, concentrations of chlorophyll and

nutrients in the Mediterranean Sea are very low, making it one of the

most oligotrophic

ocean regions in the world. The Mediterranean Sea is commonly referred

to as an LNLC (Low-Nutrient, Low-Chlorophyll) area. The Mediterranean

Sea fits the definition of a desert

as it experiences little precipitation and its nutrient contents are

low, making it difficult for plants and animals to develop.

There are intense gradients in nutrient concentrations,

chlorophyll concentrations and primary productivity in the

Mediterranean. Nutrient concentrations in the western part of the basin

are approximately two times higher than the concentrations in the

eastern basin. The Alboran Sea, close to the Strait of Gibraltar, has a daily primary productivity of about 0.25 gC m-2 day-1 whereas the eastern basin has an average daily productivity of 0.16 gC m-2 day-1.

For this reason, the eastern part of the Mediterranean Sea is termed

"ultraoligotrophic". The productive areas of the Mediterranean Sea are

few and have a small spatial extent. High (i.e. more than 0.5 grams of chlorophyll a

per cubic meter) productivity occurs in coastal areas, close to the

river mouths which are primary suppliers of dissolved nutrients. The Gulf of Lion

has a relatively high productivity because it is an area of high

vertical mixing, bringing nutrients to the surface waters that can be

used by phytoplankton to produce chlorophyll a.

Primary productivity in the Mediterranean is also marked by an

intense seasonal variability. In Winter, the strong winds and

precipitation over the basin generate vertical mixing, bringing nutrients from the deep waters to the surface, where phytoplankton can convert it into biomass.

However, in winter, light may be the limiting factor for primary

productivity. Between March and April, spring offers the ideal trade-off

between light intensity and nutrient concentrations in surface for a spring bloom to occur. In summer, high atmospheric temperatures lead to the warming of the surface Mediterranean waters. The resulting density

difference virtually isolates the surface Mediterranean waters from the

rest of the water column and nutrient exchanges are limited. As a

consequence, primary productivity is very low between June and October.

Oceanographic expeditions uncovered a characteristic feature of

the Mediterranean Sea biogeochemistry: most of the chlorophyll

production does not occur in surface, but in sub-surface waters between

80 and 200 meters deep. Another key characteristic of the Mediterranean is its high nitrogen-to-phosphorus ratio (N:P). Redfield

demonstrated that most of the world's oceans have an average N:P ratio

around 16. However, the Mediterranean Sea has an average N:P between 24

and 29, which translates a widespread phosphorus limitation.

Because of its low productivity, plankton assemblages in the Mediterranean Sea are dominated by small organisms such as picophytoplankton and bacteria.

Geology

A submarine karst spring, called vrulja, near Omiš; observed through several ripplings of an otherwise calm sea surface.

The geologic history of the Mediterranean Sea is complex. Underlain by oceanic crust, the sea basin was once thought to be a tectonic remnant of the ancient Tethys Ocean; it is now known to be a structurally younger basin, called the Neotethys, which was first formed by the convergence of the African and Eurasian plates during the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic.

Because it is a near-landlocked body of water in a normally dry

climate, the Mediterranean is subject to intensive evaporation and the

precipitation of evaporites. The Messinian salinity crisis

started about six million years ago (mya) when the Mediterranean became

landlocked, and then essentially dried up. There are salt deposits

accumulated on the bottom of the basin of more than a million cubic

kilometres—in some places more than three kilometres thick.

Scientists estimate that the sea was last filled about 5.3 million years ago (mya) in less than two years by the Zanclean flood. Water poured in from the Atlantic Ocean through a newly breached gateway now called the Strait of Gibraltar at an estimated rate of about three orders of magnitude (one thousand times) larger than the current flow of the Amazon River.

The Mediterranean Sea has an average depth of 1,500 m (4,900 ft) and the deepest recorded point is 5,267 m (17,280 ft) in the Calypso Deep in the Ionian Sea. The coastline extends for 46,000 km (29,000 mi). A shallow submarine ridge (the Strait of Sicily) between the island of Sicily and the coast of Tunisia divides the sea in two main subregions: the Western Mediterranean, with an area of about 850 thousand km2 (330 thousand mi2); and the Eastern Mediterranean, of about 1.65 million km2 (640 thousand mi2). A characteristic of the coastal Mediterranean are submarine karst springs or vruljas,

which discharge pressurised groundwater into the coastal seawater from

below the surface; the discharge water is usually fresh, and sometimes

may be thermal.

Tectonics and paleoenvironmental analysis

The Mediterranean basin and sea system was established by the ancient African-Arabian continent colliding with the Eurasian continent. As Africa-Arabia drifted northward, it closed over the ancient Tethys Ocean which had earlier separated the two supercontinents Laurasia and Gondwana.

At about that time in the middle Jurassic period (roughly 170 million years ago) a much smaller sea basin, dubbed the Neotethys,

was formed shortly before the Tethys Ocean closed at its western

(Arabian) end. The broad line of collisions pushed up a very long system

of mountains from the Pyrenees in Spain to the Zagros Mountains in Iran in an episode of mountain-building tectonics known as the Alpine orogeny.

The Neotethys grew larger during the episodes of collisions (and

associated foldings and subductions) that occurred during the Oligocene and Miocene epochs (34 to 5.33 mya): Africa-Arabia colliding with Eurasia. Accordingly, the Mediterranean basin consists of several stretched tectonic

plates in subduction which are the foundation of the Eastern part of

the Mediterranean Sea. Various zones of subduction harbour and form the deepest and most majestic oceanic ridges, east of the Ionian Sea and south of the Aegean. The Central Indian Ridge runs East of the Mediterranean Sea South-East across the in-between of Africa and the Arabian Peninsula into the Indian Ocean.

Messinian salinity crisis

Messinian salinity crisis before the Zanclean flood

During Mesozoic and Cenozoic times, as the northwest corner of Africa converged on Iberia, it lifted the Betic-Rif mountain belts

across southern Iberia and northwest Africa. There the development of

the intramontane Betic and Rif basins led to creating two

roughly-parallel marine gateways between the Atlantic Ocean and the

Mediterranean Sea. Dubbed the Betic and Rifian corridors, they progressively closed during middle and late Miocene times; perhaps several times. During late Miocene times the closure of the Betic Corridor triggered the so-called "Messinian salinity crisis"

(MSC), when the Mediterranean almost entirely dried out. The time of

beginning of the MSC was recently estimated astronomically at 5.96 mya,

and it persisted for some 630,000 years until about 5.3 mya.

After the initial drawdown and re-flooding there followed more

episodes—the total number is debated—of sea drawdowns and re-floodings

for the duration of the MSC. It ended when the Atlantic Ocean last

re-flooded the basin—creating the Strait of Gibraltar and causing the Zanclean flood—at

the end of the Miocene (5.33 mya). Some research has suggested that a

desiccation-flooding-desiccation cycle may have repeated several times,

which could explain several events of large amounts of salt deposition. Recent studies, however, show that repeated desiccation and re-flooding is unlikely from a geodynamic point of view.

Desiccation and exchanges of flora and fauna

The present-day Atlantic gateway, i.e. the Strait of Gibraltar, originated in the early Pliocene via the Zanclean Flood. As mentioned, two other gateways preceded Gibraltar: the Betic Corridor across southern Spain and the Rifian Corridor across northern Morocco. The former gateway closed about six (6) mya, causing the Messinian salinity crisis (MSC); the latter or possibly both gateways closed during the earlier Tortonian times, causing a "Tortonian salinity crisis"

(from 11.6 to 7.2 mya), which occurred well before the MSC and lasted

much longer. Both "crises" resulted in broad connections of the

mainlands of Africa and Europe, which thereby normalised migrations of

flora and fauna—especially large mammals including primates—between the

two continents. The Vallesian crisis

indicates a typical extinction and replacement of mammal species in

Europe during Tortonian times following climatic upheaval and overland

migrations of new species.

The near-completely enclosed configuration of the Mediterranean

basin has enabled the oceanic gateways to dominate seawater circulation

and the environmental evolution of the sea and basin. Circulation

patterns are also affected by several other factors—including climate,

bathymetry, and water chemistry and temperature—which are interactive

and can induce precipitation of evaporites. Deposits of evaporites accumulated earlier in the nearby Carpathian foredeep during the Middle Miocene, and the adjacent Red Sea Basin (during the Late Miocene), and in the whole Mediterranean basin (during the MSC and the Messinian age). Diatomites are regularly found underneath the evaporite deposits, suggesting a connection between their geneses.

Today, evaporation of surface seawater (output) is more than the

supply (input) of fresh water by precipitation and coastal drainage

systems, causing the salinity of the Mediterranean to be much higher

than that of the Atlantic—so much so that the saltier Mediterranean

waters sink below the waters incoming from the Atlantic, causing a

two-layer flow across the Gibraltar strait: that is, an outflow submarine current of warm saline Mediterranean water, counterbalanced by an inflow surface current of less saline cold oceanic water from the Atlantic. Herman Sörgel's Atlantropa

project proposal in the 1920s proposed a hydroelectric dam to be built

across the Strait of Gibraltar, using the inflow current to provide a

large amount of hydroelectric energy. The underlying energy grid was as

well intended to support a political union between Europe and, at least,

the Marghreb part of Africa (compare Eurafrika for the later impact and Desertec for a later project with some parallels in the planned grid).

Shift to a "Mediterranean climate"

The end of the Miocene

also marked a change in the climate of the Mediterranean basin. Fossil

evidence from that period reveals that the larger basin had a humid

subtropical climate with rainfall in the summer supporting laurel forests. The shift to a "Mediterranean climate" occurred largely within the last three million years (the late Pliocene epoch) as summer rainfall decreased. The subtropical laurel forests retreated; and even as they persisted on the islands of Macaronesia

off the Atlantic coast of Iberia and North Africa, the present

Mediterranean vegetation evolved, dominated by coniferous trees and sclerophyllous

trees and shrubs with small, hard, waxy leaves that prevent moisture

loss in the dry summers. Much of these forests and shrublands have been

altered beyond recognition by thousands of years of human habitation.

There are now very few relatively intact natural areas in what was once a

heavily wooded region.

Paleoclimate

Because

of its latitudinal position and its land-locked configuration, the

Mediterranean is especially sensitive to astronomically induced climatic

variations, which are well documented in its sedimentary record. Since

the Mediterranean is involved in the deposition of eolian dust from the Sahara during dry periods, whereas riverine detrital input prevails during wet ones, the Mediterranean marine sapropel-bearing

sequences provide high-resolution climatic information. These data have

been employed in reconstructing astronomically calibrated time scales

for the last 9 Ma of the Earth's history, helping to constrain the time

of past geomagnetic reversals.

Furthermore, the exceptional accuracy of these paleoclimatic records

has improved our knowledge of the Earth's orbital variations in the

past.

Biodiversity

Unlike the vast multidirectional Ocean currents in open Oceans within their respective Oceanic zones; biodiversity in the Mediterranean Sea is that of a stable one due to the subtle but strong locked nature of currents which affects favorably, even the smallest macroscopic type of Volcanic Life Form. The stable Marine ecosystem of the Mediterranean Sea and sea temperature provides a nourishing environment for life in the deep sea to flourish while assuring a balanced Aquatic ecosystem excluded from any external deep oceanic factors.

As a result of the drying of the sea during the Messinian salinity crisis,

the marine biota of the Mediterranean are derived primarily from the

Atlantic Ocean. The North Atlantic is considerably colder and more

nutrient-rich than the Mediterranean, and the marine life of the

Mediterranean has had to adapt to its differing conditions in the five

million years since the basin was reflooded.

The Alboran Sea

is a transition zone between the two seas, containing a mix of

Mediterranean and Atlantic species. The Alboran Sea has the largest

population of bottlenose dolphins in the Western Mediterranean, is home to the last population of harbour porpoises in the Mediterranean, and is the most important feeding grounds for loggerhead sea turtles in Europe. The Alboran sea also hosts important commercial fisheries, including sardines and swordfish. The Mediterranean monk seals live in the Aegean Sea in Greece. In 2003, the World Wildlife Fund raised concerns about the widespread drift net fishing endangering populations of dolphins, turtles, and other marine animals such as the ogre cancer.

There was a resident population of killer whale

in the Mediterranean until the 1980s, when they went extinct, probably

due to longterm PCB exposure. There are still annual sightings of killer

whale vagrants.

Environmental issues

For 4,000 years, human activity has transformed most parts of

Mediterranean Europe, and the "humanisation of the landscape" overlapped

with the appearance of the present Mediterranean climate.

The image of a simplistic, environmental determinist notion of a

Mediterranean Paradise on Earth in antiquity, which was destroyed by

later civilisations dates back to at least the 18th century and was for

centuries fashionable in archaeological and historical circles. Based on

a broad variety of methods, e.g. historical documents, analysis of

trade relations, floodplain sediments, pollen, tree-ring and further archaeometric analyses and population studies, Alfred Thomas Grove and Oliver Rackham's

work on "The Nature of Mediterranean Europe" challenges this common

wisdom of a Mediterranean Europe as a "Lost Eden", a formerly fertile

and forested region, that had been progressively degraded and

desertified by human mismanagement. The belief stems more from the failure of the recent landscape to measure up to the imaginary past of the classics as idealised by artists, poets and scientists of the early modern Enlightenment.

The historical evolution of climate, vegetation and landscape in

southern Europe from prehistoric times to the present is much more

complex and underwent various changes. For example, some of the

deforestation had already taken place before the Roman age. While in the

Roman age large enterprises as the Latifundiums took effective care of forests and agriculture, the largest depopulation effects came with the end of the empire. Some

assume that the major deforestation took place in modern times—the

later usage patterns were also quite different e.g. in southern and

northern Italy. Also, the climate has usually been unstable and showing

various ancient and modern "Little Ice Ages", and plant cover accommodated to various extremes and became resilient with regard to various patterns of human activity.

Humanisation was therefore not the cause of climate change but followed it.

The wide ecological diversity typical of Mediterranean Europe is

predominantly based on human behavior, as it is and has been closely

related human usage patterns.

The diversity range was enhanced by the widespread exchange and

interaction of the longstanding and highly diverse local agriculture,

intense transport and trade relations, and the interaction with

settlements, pasture and other land use. The greatest human-induced

changes, however, came after World War II, respectively in line with the '1950s-syndrome'

as rural populations throughout the region abandoned traditional

subsistence economies. Grove and Rackham suggest that the locals left

the traditional agricultural patterns towards taking a role as

scenery-setting agents for the then much more important (tourism)

travellers. This resulted in more monotonous, large-scale formations.

Among further current important threats to Mediterranean landscapes are

overdevelopment of coastal areas, abandonment of mountains and, as

mentioned, the loss of variety via the reduction of traditional

agricultural occupations.

Natural hazards

Stromboli volcano in Italy

The region has a variety of geological hazards which have closely

interacted with human activity and land use patterns. Among others, in

the eastern Mediterranean, the Thera eruption, dated to the 17th or 16th century BC, caused a large tsunami that some experts hypothesise devastated the Minoan civilisation on the nearby island of Crete, further leading some to believe that this may have been the catastrophe that inspired the Atlantis legend. Mount Vesuvius is the only active volcano on the European mainland, while others as Mount Etna and Stromboli are to be found on neighbouring islands. The region around Vesuvius including the Phlegraean Fields Caldera west of Naples are quite active and constitute the most densely populated volcanic region in the world where an eruptive event may occur within decades.

Vesuvius itself is regarded as quite dangerous due to a tendency towards explosive (Plinian) eruptions.

It is best known for its eruption in AD 79 that led to the burying and destruction of the Roman cities of Pompeii and Herculaneum.

The large experience of member states and regional authorities

has led to exchange on the international level with cooperation of NGOs,

states, regional and municipality authorities and private persons. The Greek–Turkish earthquake diplomacy

is a quite positive example of natural hazards leading to improved

relations of traditional rivals in the region after earthquakes in İzmir

and Athens 1999. The European Union Solidarity Fund (EUSF) was set up

to respond to major natural disasters and express European solidarity to

disaster-stricken regions within all of Europe. The largest amount of fund requests in the EU is being directed to forest fires,

followed by floodings and earthquakes. Forest fires are, whether man

made or natural, an often recurring and dangerous hazard in the

Mediterranean region. Also, tsunamis are an often underestimated hazard in the region. For example, the 1908 Messina earthquake and tsunami took more than 123,000 lives in Sicily and Calabria and is among the most deadly natural disasters in modern Europe.

Invasive species

The reticulate whipray is one of the species that colonised the Eastern Mediterranean through the Suez Canal as part of the ongoing Lessepsian migration.

The opening of the Suez Canal in 1869 created the first salt-water passage between the Mediterranean and Red Sea. The Red Sea is higher than the Eastern Mediterranean, so the canal serves as a tidal strait that pours Red Sea water into the Mediterranean. The Bitter Lakes,

which are hyper-saline natural lakes that form part of the canal,

blocked the migration of Red Sea species into the Mediterranean for many

decades, but as the salinity of the lakes gradually equalised with that

of the Red Sea, the barrier to migration was removed, and plants and

animals from the Red Sea have begun to colonise the Eastern

Mediterranean. The Red Sea is generally saltier and more nutrient-poor

than the Atlantic, so the Red Sea species have advantages over Atlantic

species in the salty and nutrient-poor Eastern Mediterranean.

Accordingly, Red Sea species invade the Mediterranean biota, and not

vice versa; this phenomenon is known as the Lessepsian migration (after Ferdinand de Lesseps, the French engineer) or Erythrean invasion. The construction of the Aswan High Dam across the Nile River in the 1960s reduced the inflow of freshwater and nutrient-rich silt

from the Nile into the Eastern Mediterranean, making conditions there

even more like the Red Sea and worsening the impact of the invasive species.

Invasive species have become a major component of the

Mediterranean ecosystem and have serious impacts on the Mediterranean

ecology, endangering many local and endemic

Mediterranean species. A first look at some groups of exotic species

show that more than 70% of the non-indigenous decapods and about 63% of

the exotic fishes occurring in the Mediterranean are of Indo Pacific

origin, introduced into the Mediterranean through the Suez Canal. This makes the Canal as the first pathway of arrival of "alien"

species into the Mediterranean. The impacts of some lessepsian species

have proven to be considerable mainly in the Levantine basin of the

Mediterranean, where they are replacing native species and becoming a

"familiar sight".

According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature definition, as well as Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD) and Ramsar Convention

terminologies, they are alien species, as they are non-native

(non-indigenous) to the Mediterranean Sea, and they are outside their

normal area of distribution which is the Indo-Pacific region. When these

species succeed in establishing populations in the Mediterranean Sea,

compete with and begin to replace native species they are "Alien

Invasive Species", as they are an agent of change and a threat to the

native biodiversity. In the context of CBD, "introduction" refers to the

movement by human agency, indirect or direct, of an alien species

outside of its natural range (past or present). The Suez Canal, being an

artificial (man made) canal, is a human agency. Lessepsian migrants are

therefore "introduced" species (indirect, and unintentional). Whatever

wording is chosen, they represent a threat to the native Mediterranean

biodiversity, because they are non-indigenous to this sea. In recent

years, the Egyptian government's announcement of its intentions to

deepen and widen the canal have raised concerns from marine biologists,

fearing that such an act will only worsen the invasion of Red Sea

species into the Mediterranean, facilitating the crossing of the canal

for yet additional species.

Arrival of new tropical Atlantic species

In

recent decades, the arrival of exotic species from the tropical

Atlantic has become a noticeable feature. Whether this reflects an

expansion of the natural area of these species that now enter the

Mediterranean through the Gibraltar strait, because of a warming trend

of the water caused by global warming;

or an extension of the maritime traffic; or is simply the result of a

more intense scientific investigation, is still an open question. While

not as intense as the "lessepsian" movement, the process may be

scientific interest and may therefore warrant increased levels of

monitoring.

Sea-level rise

By 2100 the overall level of the Mediterranean could rise between 3 to 61 cm (1.2 to 24.0 in) as a result of the effects of climate change. This could have adverse effects on populations across the Mediterranean:

- Rising sea levels will submerge parts of Malta. Rising sea levels will also mean rising salt water levels in Malta's groundwater supply and reduce the availability of drinking water.

- A 30 cm (12 in) rise in sea level would flood 200 square kilometres (77 sq mi) of the Nile Delta, displacing over 500,000 Egyptians.

Coastal ecosystems also appear to be threatened by sea level rise, especially enclosed seas such as the Baltic, the Mediterranean and the Black Sea. These seas have only small and primarily east-west movement corridors, which may restrict northward displacement of organisms in these areas.

Sea level rise for the next century (2100) could be between 30 cm

(12 in) and 100 cm (39 in) and temperature shifts of a mere 0.05–0.1 °C

in the deep sea are sufficient to induce significant changes in species

richness and functional diversity.

Pollution

Pollution in this region has been extremely high in recent years. The United Nations Environment Programme has estimated that 650,000,000 t (720,000,000 short tons) of sewage, 129,000 t (142,000 short tons) of mineral oil, 60,000 t (66,000 short tons) of mercury, 3,800 t (4,200 short tons) of lead and 36,000 t (40,000 short tons) of phosphates are dumped into the Mediterranean each year. The Barcelona Convention

aims to 'reduce pollution in the Mediterranean Sea and protect and

improve the marine environment in the area, thereby contributing to its

sustainable development.'

Many marine species have been almost wiped out because of the sea's pollution. One of them is the Mediterranean monk seal which is considered to be among the world's most endangered marine mammals.

The Mediterranean is also plagued by marine debris. A 1994 study of the seabed using trawl nets

around the coasts of Spain, France and Italy reported a particularly

high mean concentration of debris; an average of 1,935 items per km2. Plastic debris accounted for 76%, of which 94% was plastic bags.

Shipping

A cargo ship cruises towards the Strait of Messina

Some of the world's busiest shipping routes are in the Mediterranean Sea. It is estimated that approximately 220,000 merchant vessels of more than 100 tonnes

cross the Mediterranean Sea each year—about one third of the world's

total merchant shipping. These ships often carry hazardous cargo, which

if lost would result in severe damage to the marine environment.

The discharge of chemical tank washings and oily wastes also

represent a significant source of marine pollution. The Mediterranean

Sea constitutes 0.7% of the global water surface and yet receives 17% of

global marine oil pollution. It is estimated that every year between

100,000 t (98,000 long tons) and 150,000 t (150,000 long tons) of crude

oil are deliberately released into the sea from shipping activities.

Approximately 370,000,000 t (360,000,000 long tons) of oil are

transported annually in the Mediterranean Sea (more than 20% of the

world total), with around 250–300 oil tankers crossing the sea every day. Accidental oil spills

happen frequently with an average of 10 spills per year. A major oil

spill could occur at any time in any part of the Mediterranean.

Tourism

Antalya on the Turkish Riviera (Turquoise Coast) received more than 11 million international tourist arrivals in 2014.

The Mediterranean Sea is arguably among the most culturally diverse

block basin sea regions in the world, with a unique combination of

pleasant climate, beautiful coastline, rich history and various

cultures. The Mediterranean region is the most popular tourist

destination in the world—attracting approximately one third of the

world's international tourists.

Tourism is one of the most important sources of income for many

Mediterranean countries regardless of the man-made geopolitical

conflicts that harbour coastal nations. In that regard, authorities

around the Mediterranean have made it a point to extinguish rising

man-made chaotic zones that would affect the economies, societies in

neighboring coastal countries, let alone shipping routes.

Naval and rescue components in the Mediterranean Sea are considered one

of the very best due to the quick intercooperation of various Naval Fleets within proximity of each other. Unlike the vast open Oceans,

the closed nature of the Mediterranean Sea provides a much more

adaptable naval initiative among the coastal countries to provide

effective naval and rescue missions, considered the safest and

regardless of any man-made or natural disaster.

Tourism also supports small communities in coastal areas and

islands by providing alternative sources of income far from urban

centers. However, tourism has also played major role in the degradation of the coastal and marine environment.

Rapid development has been encouraged by Mediterranean governments to

support the large numbers of tourists visiting the region each year. But

this has caused serious disturbance to marine habitats such as erosion and pollution in many places along the Mediterranean coasts.

Tourism often concentrates in areas of high natural wealth,

causing a serious threat to the habitats of endangered Mediterranean

species such as sea turtles and monk seals. Reductions in natural wealth may reduce incentives for tourists to visit.

Overfishing

Fish stock levels in the Mediterranean Sea are alarmingly low. The

European Environment Agency says that more than 65% of all fish stocks

in the region are outside safe biological limits and the United Nations

Food and Agriculture Organisation, that some of the most important

fisheries—such as albacore and bluefin tuna, hake, marlin, swordfish, red mullet and sea bream—are threatened.

There are clear indications that catch size and quality have

declined, often dramatically, and in many areas larger and longer-lived

species have disappeared entirely from commercial catches.

Large open water fish like tuna have been a shared fisheries

resource for thousands of years but the stocks are now dangerously low.

In 1999, Greenpeace

published a report revealing that the amount of bluefin tuna in the

Mediterranean had decreased by over 80% in the previous 20 years and

government scientists warn that without immediate action the stock will

collapse.