| |

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

β-D-Fructofuranosyl α-D-glucopyranoside

| |

| Systematic IUPAC name

(2R,3R,4S,5S,6R)-2-[(2S,3S,4S,5R)-3,4-dihydroxy-2,5-bis(hydroxymethyl)oxolan-2-yl]oxy-6-(hydroxymethyl)oxane-3,4,5-triol

| |

Other names

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| DrugBank | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.000.304 |

| EC Number | 200-334-9 |

PubChem CID

|

|

| RTECS number | WN6500000 |

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| Properties | |

| C12H22O11 | |

| Molar mass | 342.30 g/mol |

| Appearance | white solid |

| Density | 1.587 g/cm3, solid |

| Melting point | None; decomposes at 186 °C (367 °F; 459 K) |

| ~200 g/dL (25 °C) | |

| log P | −3.76 |

| Structure | |

| Monoclinic | |

| P21 | |

| Thermochemistry | |

Std enthalpy of

combustion (ΔcH⦵298) |

1,349.6 kcal/mol (5,647 kJ/mol) (Higher heating value) |

| Hazards | |

| Safety data sheet | ICSC 1507 |

| NFPA 704 | |

| Lethal dose or concentration (LD, LC): | |

LD50 (median dose)

|

29700 mg/kg (oral, rat) |

| US health exposure limits (NIOSH): | |

PEL (Permissible)

|

TWA 15 mg/m3 (total) TWA 5 mg/m3 (resp) |

REL (Recommended)

|

TWA 10 mg/m3 (total) TWA 5 mg/m3 (resp) |

IDLH (Immediate danger)

|

N.D. |

| Related compounds | |

Related compounds

|

Lactose Maltose |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

Sucrose is common sugar. It is a disaccharide, a molecule composed of two monosaccharides: glucose and fructose. Sucrose is produced naturally in plants, from which table sugar is refined. It has the molecular formula C12H22O11.

For human consumption, sucrose is extracted, and refined, from either sugar cane or sugar beet. Sugar mills are located where sugarcane is grown to crush the cane and produce raw sugar which is shipped around the world for refining into pure sucrose. Some sugar mills also process the raw sugar into pure sucrose. Sugar beet factories are located in colder climates where the beet is grown and process the beets directly into refined sugar. The sugar refining process involves washing the raw sugar crystals before dissolving them into a sugar syrup which is filtered and then passed over carbon to remove any residual colour. The by-now clear sugar syrup is then concentrated by boiling under a vacuum and crystallized as the final purification process to produce crystals of pure sucrose. These crystals are clear, odourless, and have a sweet taste. En masse, the crystals appear white.

Sugar is often an added ingredient in food production and food recipes. About 185 million tonnes of sugar were produced worldwide in 2017.

Etymology

The word sucrose was coined in 1857 by the English chemist William Miller from the French sucre ("sugar") and the generic chemical suffix for sugars -ose. The abbreviated term Suc is often used for sucrose in scientific literature.

The name saccharose was coined in 1860 by the French chemist Marcellin Berthelot. Saccharose is an obsolete name for sugars in general, especially sucrose.

Physical and chemical properties

Structural O-α-D-glucopyranosyl-(1→2)-β-D-fructofuranoside

In sucrose, the components glucose and fructose are linked via an ether bond between C1 on the glucosyl subunit and C2 on the fructosyl unit. The bond is called a glycosidic linkage.

Glucose exists predominantly as two isomeric "pyranoses" (α and β), but

only one of these forms links to the fructose. Fructose itself exists

as a mixture of "furanoses", each of which having α and β isomers, but

only one particular isomer links to the glucosyl unit. What is notable

about sucrose is that, unlike most disaccharides, the glycosidic bond is

formed between the reducing ends of both glucose and fructose, and not

between the reducing end of one and the nonreducing end of the other.

This linkage inhibits further bonding to other saccharide units. Since

it contains no anomeric hydroxyl groups, it is classified as a non-reducing sugar.

Sucrose crystallizes in the monoclinic space group P21 with room-temperature lattice parameters a = 1.08631 nm, b = 0.87044 nm, c = 0.77624 nm, β = 102.938°.

The purity of sucrose is measured by polarimetry, through the rotation of plane-polarized light by a solution of sugar. The specific rotation

at 20 °C using yellow "sodium-D" light (589 nm) is +66.47°. Commercial

samples of sugar are assayed using this parameter. Sucrose does not

deteriorate at ambient conditions.

Thermal and oxidative degradation

Sucrose does not melt at high temperatures. Instead, it decomposes at 186 °C (367 °F) to form caramel. Like other carbohydrates, it combusts to carbon dioxide and water. Mixing sucrose with the oxidizer potassium nitrate produces the fuel known as rocket candy that is used to propel amateur rocket motors.

- C12H22O11 + 6 KNO3 → 9 CO + 3 N2 + 11 H2O + 3 K2CO3

This reaction is somewhat simplified though. Some of the carbon does

get fully oxidized to carbon dioxide, and other reactions, such as the water-gas shift reaction also take place. A more accurate theoretical equation is:

- C12H22O11 + 6.288 KNO3 → 3.796 CO2 + 5.205 CO + 7.794 H2O + 3.065 H2 + 3.143 N2 + 2.998 K2CO3 + 0.274 KOH

Sucrose burns with chloric acid, formed by the reaction of hydrochloric acid and potassium chlorate:

- 8 HClO3 + C12H22O11 → 11 H2O + 12 CO2 + 8 HCl

Sucrose can be dehydrated with sulfuric acid to form a black, carbon-rich solid, as indicated in the following idealized equation:

- H2SO4(catalyst) + C12H22O11 → 12 C + 11 H2O + Heat (and some H2O + SO3 as a result of the heat).

The formula for sucrose's decomposition can be represented as a

two-step reaction: the first simplified reaction is dehydration of

sucrose to pure carbon and water, and then carbon oxidises to CO2 with O2 from air.

- C12H22O11 + heat → 12 C + 11 H2O

- 12 C + 12 O2 → 12 CO2

Hydrolysis

Hydrolysis breaks the glycosidic bond converting sucrose into glucose and fructose. Hydrolysis is, however, so slow that solutions of sucrose can sit for years with negligible change. If the enzyme sucrase is added, however, the reaction will proceed rapidly. Hydrolysis can also be accelerated with acids, such as cream of tartar

or lemon juice, both weak acids. Likewise, gastric acidity converts

sucrose to glucose and fructose during digestion, the bond between them

being an acetal bond which can be broken by an acid.

Given (higher) heats of combustion of 1349.6 kcal/mol for sucrose, 673.0 for glucose, and 675.6 for fructose, hydrolysis releases about 1.0 kcal (4.2 kJ) per mole of sucrose, or about 3 small calories per gram of product.

Synthesis and biosynthesis of sucrose

The biosynthesis of sucrose proceeds via the precursors UDP-glucose and fructose 6-phosphate, catalyzed by the enzyme sucrose-6-phosphate synthase. The energy for the reaction is gained by the cleavage of uridine diphosphate (UDP).

Sucrose is formed by plants and cyanobacteria but not by other organisms. Sucrose is found naturally in many food plants along with the monosaccharide fructose. In many fruits, such as pineapple and apricot, sucrose is the main sugar. In others, such as grapes and pears, fructose is the main sugar.

Chemical synthesis

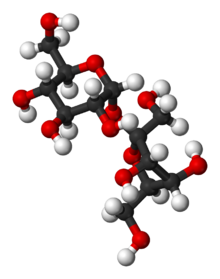

Model of sucrose molecule

Although sucrose is almost invariably isolated from natural sources, its chemical synthesis was first achieved in 1953 by Raymond Lemieux.

Sources

In nature, sucrose is present in many plants, and in particular their roots, fruits and nectars, because it serves as a way to store energy, primarily from photosynthesis.

Many mammals, birds, insects and bacteria accumulate and feed on the

sucrose in plants and for some it is their main food source. Seen from a

human consumption perspective, honeybees are especially important because they accumulate sucrose and produce honey, an important foodstuff all over the world. The carbohydrates in honey itself primarily consist of fructose and glucose with trace amounts of sucrose only.

As fruits ripen, their sucrose content usually rises sharply, but

some fruits contain almost no sucrose at all. This includes grapes,

cherries, blueberries, blackberries, figs, pomegranates, tomatoes,

avocados, lemons and limes.

Sucrose is a naturally occurring sugar, but with the advent of industrialization, it has been increasingly refined and consumed in all kinds of processed foods.

Production

History of sucrose refinement

Table sugar production in the 19th century. Sugar cane

plantations (upper image) employed slave or indentured laborers. The

picture shows workers harvesting cane, loading it on a boat for

transport to the plant, while a European overseer watches in the lower

right. The lower image shows a sugar plant with two furnace chimneys.

Sugar plants and plantations were harsh, inhumane work.

A sugarloaf was a traditional form for sugar from the 17th to 19th centuries. Sugar nips were required to break off pieces.

The production of table sugar has a long history. Some scholars claim Indians discovered how to crystallize sugar during the Gupta dynasty, around AD 350.

Other scholars point to the ancient manuscripts of China, dated

to the 8th century BC, where one of the earliest historical mentions of sugar cane is included along with the fact that their knowledge of sugar cane was derived from India.

Further, it appears that by about 500 BC, residents of present-day

India began making sugar syrup and cooling it in large flat bowls to

make raw table sugar crystals that were easier to store and transport.

In the local Indian language, these crystals were called khanda (खण्ड), which is the source of the word candy.

The army of Alexander the Great was halted on the banks of river Indus by the refusal of his troops to go further east. They saw people in the Indian subcontinent growing sugarcane and making granulated, salt-like sweet powder, locally called sākhar (साखर), pronounced as sakcharon (ζακχαρον) in Greek (Modern Greek, zachari

ζάχαρη). On their return journey, the Greek soldiers carried back some

of the "honey-bearing reeds". Sugarcane remained a limited crop for over

a millennium. Sugar was a rare commodity and traders of sugar became

wealthy. Venice, at the height of its financial power, was the chief

sugar-distributing center of Europe. Arabs started producing it in Sicily and Spain. Only after the Crusades did it begin to rival honey as a sweetener in Europe. The Spanish began cultivating sugarcane in the West Indies in 1506 (Cuba in 1523). The Portuguese first cultivated sugarcane in Brazil in 1532.

Sugar remained a luxury in much of the world until the 18th

century. Only the wealthy could afford it. In the 18th century, the

demand for table sugar boomed in Europe and by the 19th century it had

become regarded as a human necessity. The use of sugar grew from use in tea, to cakes, confectionery and chocolates. Suppliers marketed sugar in novel forms, such as solid cones, which required consumers to use a sugar nip, a pliers-like tool, in order to break off pieces.

The demand for cheaper table sugar drove, in part, colonization

of tropical islands and nations where labor-intensive sugarcane

plantations and table sugar manufacturing could thrive. Growing sugar

cane crop in hot humid climates, and producing table sugar in high

temperature sugar mills was harsh, inhumane work. The demand for cheap

and docile labor for this work, in part, first drove slave trade from

Africa (in particular West Africa), followed by indentured labor trade

from South Asia (in particular India).

Millions of slaves, followed by millions of indentured laborers were

brought into the Caribbean, Indian Ocean, Pacific Islands, East Africa,

Natal, north and eastern parts of South America, and southeast Asia. The

modern ethnic mix of many nations, settled in the last two centuries,

has been influenced by table sugar.

Beginning in the late 18th century, the production of sugar became increasingly mechanized. The steam engine first powered a sugar mill in Jamaica

in 1768, and, soon after, steam replaced direct firing as the source of

process heat. During the same century, Europeans began experimenting

with sugar production from other crops. Andreas Marggraf identified sucrose in beet root and his student Franz Achard built a sugar beet processing factory in Silesia (Prussia). The beet-sugar industry took off during the Napoleonic Wars,

when France and the continent were cut off from Caribbean sugar. In

2010, about 20 percent of the world's sugar was produced from beets.

Today, a large beet refinery producing around 1,500 tonnes of

sugar a day needs a permanent workforce of about 150 for 24-hour

production.

Trends

A table sugar factory in England. The tall diffusers

are visible to the middle left where the harvest transforms into a

sugar syrup. The boiler and furnace are in the center, where table sugar

crystals form. An expressway for transport is visible in the lower

left.

Table sugar (sucrose) comes from plant sources. Two important sugar crops predominate: sugarcane (Saccharum spp.) and sugar beets (Beta vulgaris), in which sugar can account for 12% to 20% of the plant's dry weight. Minor commercial sugar crops include the date palm (Phoenix dactylifera), sorghum (Sorghum vulgare), and the sugar maple (Acer saccharum).

Sucrose is obtained by extraction of these crops with hot water;

concentration of the extract gives syrups, from which solid sucrose can

be crystallized. In 2017, worldwide production of table sugar amounted

to 185 million tonnes.

Most cane sugar comes from countries with warm climates, because

sugarcane does not tolerate frost. Sugar beets, on the other hand, grow

only in cooler temperate regions and do not tolerate extreme heat. About

80 percent of sucrose is derived from sugarcane, the rest almost all

from sugar beets.

In mid-2018, India and Brazil had about the same production of sugar – 34 million tonnes – followed by the European Union, Thailand, and China as the major producers. India, the European Union, and China were the leading domestic consumers of sugar in 2018.

Beet sugar comes from regions with cooler climates: northwest and

eastern Europe, northern Japan, plus some areas in the United States

(including California). In the northern hemisphere, the beet-growing

season ends with the start of harvesting around September. Harvesting

and processing continues until March in some cases. The availability of

processing plant capacity and the weather both influence the duration of

harvesting and processing – the industry can store harvested beets

until processed, but a frost-damaged beet becomes effectively

unprocessable.

The United States sets high sugar prices to support its

producers, with the effect that many former purchasers of sugar have

switched to corn syrup (beverage manufacturers) or moved out of the country (candy manufacturers).

The low prices of glucose syrups produced from wheat and corn (maize) threaten the traditional sugar market. Used in combination with artificial sweeteners, they can allow drink manufacturers to produce very low-cost goods.

High-fructose corn syrup

In the United States, there are tariffs on the importation of sugar, and subsidies for the production of maize

(corn). High-fructose corn syrup (HFCS) is significantly cheaper than

refined sucrose as a sweetener. This has led to sucrose being partially

displaced in U.S. industrial food production by HFCS and other

non-sucrose natural sweeteners.

Some people regard HFCS as unhealthy. Clinical nutritionists, medical authorities, and the United States Food and Drug Administration

have dismissed such concerns because "Sucrose, HFCS, invert sugar,

honey, and many fruits and juices deliver the same sugars in the same

ratios to the same tissues within the same time frame to the same

metabolic pathways". While scientific authorities agree that dietary sugars are a source of empty calories

associated with certain health problems, the belief that

glucose-fructose syrups such as HFCS are especially unhealthy is not

supported by scientific evidence. The FDA does endorse limiting the

consumption of all added sugars, including HFCS.

Types

Cane

Harvested sugarcane from Venezuela ready for processing

Since the 6th century BC, cane sugar producers have crushed the

harvested vegetable material from sugarcane in order to collect and

filter the juice. They then treat the liquid (often with lime (calcium oxide))

to remove impurities and then neutralize it. Boiling the juice then

allows the sediment to settle to the bottom for dredging out, while the

scum rises to the surface for skimming off. In cooling, the liquid

crystallizes, usually in the process of stirring, to produce sugar

crystals. Centrifuges

usually remove the uncrystallized syrup. The producers can then either

sell the sugar product for use as is, or process it further to produce

lighter grades. The later processing may take place in another factory

in another country.

Sugarcane is a major component of Brazilian agriculture; the

country is the world's largest producer of sugarcane and its derivative

products, such as crystallized sugar and ethanol (ethanol fuel).

Beet

Sugar beets

Beet sugar producers slice the washed beets, then extract the sugar with hot water in a "diffuser". An alkaline solution ("milk of lime" and carbon dioxide from the lime kiln) then serves to precipitate impurities (see carbonatation). After filtration,

evaporation concentrates the juice to a content of about 70% solids,

and controlled crystallisation extracts the sugar. A centrifuge removes

the sugar crystals from the liquid, which gets recycled in the

crystalliser stages. When economic constraints prevent the removal of

more sugar, the manufacturer discards the remaining liquid, now known as

molasses, or sells it on to producers of animal feed.

Sieving the resultant white sugar produces different grades for selling.

Cane versus beet

It is difficult to distinguish between fully refined sugar produced from beet and cane. One way is by isotope analysis of carbon. Cane uses C4 carbon fixation, and beet uses C3 carbon fixation, resulting in a different ratio of 13C and 12C isotopes in the sucrose. Tests are used to detect fraudulent abuse of European Union subsidies or to aid in the detection of adulterated fruit juice.

Sugar cane tolerates hot climates better, but the production of

sugar cane needs approximately four times as much water as the

production of sugar beet. As a result, some countries that traditionally

produced cane sugar (such as Egypt)

have built new beet sugar factories since about 2008. Some sugar

factories process both sugar cane and sugar beets and extend their

processing period in that way.

The production of sugar leaves residues that differ substantially

depending on the raw materials used and on the place of production.

While cane molasses

is often used in food preparation, humans find molasses from sugar

beets unpalatable, and it consequently ends up mostly as industrial fermentation feedstock (for example in alcohol distilleries), or as animal feed. Once dried, either type of molasses can serve as fuel for burning.

Pure beet sugar is difficult to find, so labelled, in the

marketplace. Although some makers label their product clearly as "pure

cane sugar", beet sugar is almost always labeled simply as sugar or pure

sugar. Interviews with the 5 major beet sugar-producing companies

revealed that many store brands or "private label" sugar products are

pure beet sugar. The lot code can be used to identify the company and

the plant from which the sugar came, enabling beet sugar to be

identified if the codes are known.

Culinary sugars

Grainy raw sugar

Mill white

Mill white, also called plantation white, crystal sugar or superior sugar is produced from raw sugar. It is exposed to sulfur dioxide

during the production to reduce the concentration of color compounds

and helps prevent further color development during the crystallization

process. Although common to sugarcane-growing areas, this product does

not store or ship well. After a few weeks, its impurities tend to

promote discoloration and clumping; therefore this type of sugar is

generally limited to local consumption.

Blanco directo

Blanco

directo, a white sugar common in India and other south Asian countries,

is produced by precipitating many impurities out of cane juice using phosphoric acid and calcium hydroxide, similar to the carbonatation technique used in beet sugar refining. Blanco directo is more pure than mill white sugar, but less pure than white refined.

White refined

White refined is the most common form of sugar in North America and

Europe. Refined sugar is made by dissolving and purifying raw sugar

using phosphoric acid similar to the method used for blanco directo, a carbonatation

process involving calcium hydroxide and carbon dioxide, or by various

filtration strategies. It is then further purified by filtration through

a bed of activated carbon or bone char. Beet sugar refineries produce refined white sugar directly without an intermediate raw stage.

White refined sugar is typically sold as granulated sugar, which has been dried to prevent clumping and comes in various crystal sizes for home and industrial use:

Sugars; clockwise from top left: Refined, unrefined, brown, unprocessed cane

- Coarse-grain, such as sanding sugar (also called "pearl sugar", "decorating sugar", nibbed sugar or sugar nibs) is a coarse grain sugar used to add sparkle and flavor atop baked goods and candies. Its large reflective crystals will not dissolve when subjected to heat.

- Granulated, familiar as table sugar, with a grain size about 0.5 mm across. "Sugar cubes" are lumps for convenient consumption produced by mixing granulated sugar with sugar syrup.

- Caster (or castor) (0.35 mm), a very fine sugar in Britain and other Commonwealth countries, so-named because the grains are small enough to fit through a castor which is small vessel with a perforated top, from which to sprinkle sugar at table. Commonly used in baking and mixed drinks, it is sold as "superfine" sugar in the United States. Because of its fineness, it dissolves faster than regular white sugar and is especially useful in meringues and cold liquids. Castor sugar can be prepared at home by grinding granulated sugar for a couple of minutes in a mortar or food processor.

- Powdered, 10X sugar, confectioner's sugar (0.060 mm), or icing sugar (0.024 mm), produced by grinding sugar to a fine powder. The manufacturer may add a small amount of anticaking agent to prevent clumping — either cornstarch (1% to 3%) or tri-calcium phosphate.

Brown sugar crystals

Brown sugar comes either from the late stages of cane sugar refining, when sugar forms fine crystals with significant molasses

content, or from coating white refined sugar with a cane molasses syrup

(blackstrap molasses). Brown sugar's color and taste becomes stronger

with increasing molasses content, as do its moisture-retaining

properties. Brown sugars also tend to harden if exposed to the

atmosphere, although proper handling can reverse this.

Measurement

Dissolved sugar content

Scientists and the sugar industry use degrees Brix (symbol °Bx), introduced by Adolf Brix,

as units of measurement of the mass ratio of dissolved substance to

water in a liquid. A 25 °Bx sucrose solution has 25 grams of sucrose per

100 grams of liquid; or, to put it another way, 25 grams of sucrose

sugar and 75 grams of water exist in the 100 grams of solution.

The Brix degrees are measured using an infrared sensor. This

measurement does not equate to Brix degrees from a density or refractive

index measurement, because it will specifically measure dissolved sugar

concentration instead of all dissolved solids. When using a

refractometer, one should report the result as "refractometric dried substance" (RDS). One might speak of a liquid as having 20 °Bx RDS. This refers to a measure of percent by weight of total

dried solids and, although not technically the same as Brix degrees

determined through an infrared method, renders an accurate measurement

of sucrose content, since sucrose in fact forms the majority of dried

solids. The advent of in-line infrared Brix measurement sensors has made

measuring the amount of dissolved sugar in products economical using a

direct measurement.

Consumption

Refined sugar was a luxury before the 18th century. It became widely

popular in the 18th century, then graduated to becoming a necessary food

in the 19th century. This evolution of taste and demand for sugar as an

essential food ingredient unleashed major economic and social changes. Eventually, table sugar became sufficiently cheap and common enough to influence standard cuisine and flavored drinks.

Sucrose forms a major element in confectionery and desserts.

Cooks use it for sweetening — its fructose component, which has almost

double the sweetness of glucose, makes sucrose distinctively sweet in

comparison to other carbohydrates. It can also act as a food preservative

when used in sufficient concentrations. Sucrose is important to the

structure of many foods, including biscuits and cookies, cakes and pies,

candy, and ice cream and sorbets. It is a common ingredient in many

processed and so-called "junk foods".

Nutritional information

| Nutritional value per 100 g (3.5 oz) | |

|---|---|

| Energy | 1,620 kJ (390 kcal) |

100 g

| |

0 g

| |

0 g

| |

| Vitamins | Quantity %DV† |

| Thiamine (B1) |

0%

0 mg |

| Riboflavin (B2) |

0%

0 mg |

| Niacin (B3) |

0%

0 mg |

| Vitamin C |

0%

0 mg |

| Minerals | Quantity %DV† |

| Iron |

0%

0 mg |

| Phosphorus |

0%

0 mg |

| Potassium |

0%

2.0 mg |

| Selenium |

1%

0.6 μg |

| |

| †Percentages are roughly approximated using US recommendations for adults. Source: USDA Nutrient Database | |

Fully refined sugar is 99.9% sucrose, thus providing only carbohydrate as dietary nutrient and 390 kilocalories per 100 g serving (USDA data, right table). There are no micronutrients of significance in fully refined sugar (right table).

Metabolism of sucrose

Granulated sucrose

In humans and other mammals, sucrose is broken down into its constituent monosaccharides, glucose and fructose, by sucrase or isomaltase glycoside hydrolases, which are located in the membrane of the microvilli lining the duodenum. The resulting glucose and fructose molecules are then rapidly absorbed into the bloodstream. In bacteria and some animals, sucrose is digested by the enzyme invertase. Sucrose is an easily assimilated macronutrient that provides a quick source of energy, provoking a rapid rise in blood glucose upon ingestion. Sucrose, as a pure carbohydrate, has an energy content of 3.94 kilocalories per gram (or 17 kilojoules per gram).

If consumed excessively, sucrose may contribute to the development of metabolic syndrome, including increased risk for type 2 diabetes, weight gain and obesity in adults and children.

Tooth decay

Tooth decay

(dental caries) has become a pronounced health hazard associated with

the consumption of sugars, especially sucrose. Oral bacteria such as Streptococcus mutans live in dental plaque and metabolize any sugars (not just sucrose, but also glucose, lactose, fructose, and cooked starches) into lactic acid. The resultant lactic acid lowers the pH of the tooth's surface, stripping it of minerals in the process known as tooth decay.

All 6-carbon sugars and disaccharides based on 6-carbon sugars

can be converted by dental plaque bacteria into acid that demineralizes

teeth, but sucrose may be uniquely useful to Streptococcus sanguinis (formerly Streptococcus sanguis) and Streptococcus mutans.

Sucrose is the only dietary sugar that can be converted to sticky

glucans (dextran-like polysaccharides) by extracellular enzymes. These

glucans allow the bacteria to adhere to the tooth surface and to build

up thick layers of plaque. The anaerobic conditions deep in the plaque

encourage the formation of acids, which leads to carious lesions. Thus,

sucrose could enable S. mutans, S. sanguinis and many

other species of bacteria to adhere strongly and resist natural removal,

e.g. by flow of saliva, although they are easily removed by brushing.

The glucans and levans (fructose polysaccharides) produced by the plaque

bacteria also act as a reserve food supply for the bacteria.

Such a special role of sucrose in the formation of tooth decay is much

more significant in light of the almost universal use of sucrose as the

most desirable sweetening agent. Widespread replacement of sucrose by high-fructose corn syrup

(HFCS) has not diminished the danger from sucrose. If smaller amounts

of sucrose are present in the diet, they will still be sufficient for

the development of thick, anaerobic plaque and plaque bacteria will

metabolise other sugars in the diet, such as the glucose and fructose in HFCS.

Glycemic index

Sucrose is a disaccharide made up of 50% glucose and 50% fructose and has a glycemic index of 65. Sucrose is digested rapidly, but has a relatively low glycemic index due to its content of fructose, which has a minimal effect on blood glucose.

As with other sugars, sucrose is digested into its components via the enzyme sucrase

to glucose (blood sugar) and fructose. The glucose component is

transported into the blood where it serves immediate metabolic demands,

or is converted and reserved in the liver as glycogen.

Gout

The occurrence of gout

is connected with an excess production of uric acid. A diet rich in

sucrose may lead to gout as it raises the level of insulin, which

prevents excretion of uric acid from the body. As the concentration of

uric acid in the body increases, so does the concentration of uric acid

in the joint liquid and beyond a critical concentration, the uric acid

begins to precipitate into crystals. Researchers have implicated sugary

drinks high in fructose in a surge in cases of gout.

UN dietary recommendation

In 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO)

published a new guideline on sugars intake for adults and children, as a

result of an extensive review of the available scientific evidence by a

multidisciplinary group of experts. The guideline recommends that both

adults and children reduce the intake of free sugars (monosaccharides

and disaccharides added to foods and beverages by the manufacturer, cook

or consumer, and sugars naturally present in honey, syrups, fruit

juices and fruit juice concentrates) to less than 10% of total energy

intake. A reduction to below 5% of total energy intake brings additional

health benefits, especially in what regards dental caries.

Religious concerns

The sugar refining industry often uses bone char (calcinated animal bones) for decolorizing. About 25% of sugar produced in the U.S. is processed using bone char as a filter, the remainder being processed with activated carbon. As bone char does not seem to remain in finished sugar, Jewish religious leaders consider sugar filtered through it to be pareve,

meaning that it is neither meat nor dairy and may be used with either

type of food. However, the bone char must source to a kosher animal

(e.g. cow, sheep) for the sugar to be kosher.

Trade and economics

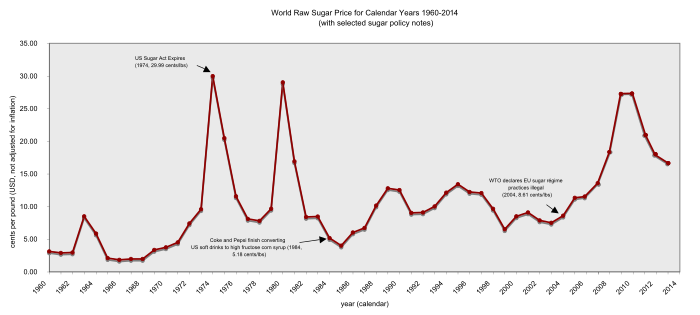

One

of the most widely-traded commodities in the world throughout history,

sugar accounts for around 2% of the global dry cargo market. International sugar prices show great volatility, ranging from around 3 to over 60 cents per pound in the past

50 years. About 100 of the world's 180 countries produce sugar from

beet or cane, a few more refine raw sugar to produce white sugar, and

all countries consume sugar. Consumption of sugar ranges from around 3

kilograms per person per annum in Ethiopia to around 40 kg/person/yr in

Belgium.

Consumption per capita rises with income per capita until it reaches a

plateau of around 35 kg per person per year in middle income countries.

Many countries subsidize sugar production heavily. The European

Union, the United States, Japan, and many developing countries subsidize

domestic production and maintain high tariffs on imports. Sugar prices

in these countries have often exceeded prices on the international

market by up to three times; today, with world market sugar futures prices currently strong, such prices typically exceed world prices by two times.

Within international trade bodies, especially in the World Trade Organization, the "G20"

countries led by Brazil have long argued that, because these sugar

markets in essence exclude cane sugar imports, the G20 sugar producers

receive lower prices than they would under free trade. While both the European Union and United States maintain trade agreements whereby certain developing and less developed countries

(LDCs) can sell certain quantities of sugar into their markets, free of

the usual import tariffs, countries outside these preferred trade

régimes have complained that these arrangements violate the "most favoured nation" principle of international trade. This has led to numerous tariffs and levies in the past.

In 2004, the WTO

sided with a group of cane sugar exporting nations (led by Brazil and

Australia) and ruled the EU sugar-régime and the accompanying ACP-EU

Sugar Protocol (whereby a group of African, Caribbean, and Pacific

countries receive preferential access to the European sugar market)

illegal.

In response to this and to other rulings of the WTO, and owing to

internal pressures on the EU sugar-régime, the European Commission

proposed on 22 June 2005 a radical reform of the EU sugar-régime,

cutting prices by 39% and eliminating all EU sugar exports.

The African, Caribbean, Pacific and least developed country sugar exporters reacted with dismay to the EU sugar proposals. On 25 November 2005, the Council of the EU agreed to cut EU sugar prices by 36% as from 2009. In 2007, it seemed

that the U.S. Sugar Program

could become the next target for reform. However, some commentators

expected heavy lobbying from the U.S. sugar industry, which donated $2.7

million to US House and US Senate incumbents in the 2006 US election,

more than any other group of US food-growers.

Especially prominent lobbyists include The Fanjul Brothers, so-called "sugar barons" who made the single largest individual contributions of soft money to both the Democratic and Republican parties in the political system of the United States of America.

Small quantities of sugar, especially specialty grades of sugar, reach the market as 'fair trade' commodities; the fair trade

system produces and sells these products with the understanding that a

larger-than-usual fraction of the revenue will support small farmers in

the developing world. However, whilst the Fairtrade Foundation offers a

premium of $60.00 per tonne to small farmers for sugar branded as

"Fairtrade", government schemes such as the U.S. Sugar Program and the ACP Sugar Protocol

offer premiums of around $400.00 per tonne above world market prices.

However, the EU announced on 14 September 2007 that it had offered "to

eliminate all duties and quotas on the import of sugar into the EU".

The US Sugar Association has launched a campaign to promote sugar over artificial substitutes. The Association now

aggressively challenges many common beliefs regarding negative

side-effects of sugar consumption. The campaign aired a high-profile

television commercial during the 2007 Primetime Emmy Awards on FOX Television. The Sugar Association uses the trademark tagline "Sugar: sweet by nature".